December 28, 2023, rewritten June 2024 for the printed version

By Gregory Nagy

“Sappho” (1888). Gustav Klimt (1862–1918).

Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Preface

This book about the songs of Sappho is one of three interrelated volumes published online by Classical Continuum (2023) and then in print by ΕΠΟΨ Publishers (2024).

As I declare already in the title of this book, Sappho from ground zero, my primary aim is to reconstruct, as far back in time as possible, the very beginnings of traditions in songmaking that culminated in Sappho’s poetic language. The beginnings—and that would be ground zero—are for the most part unreachable, and even the text of most of her songs has not survived. Nevertheless, reconstructions backward in time can still aim at ground zero. In the Introduction, I will explain further what I mean, based on my early academic formation as a linguist.

The other two books in this set of three books about Sappho are organized as a pair. Even their titles are paired. Sappho I, Version Alpha via Beta: Essays on ancient performances of her songs is matched with Sappho II, Version Beta: Essays on ancient imitations of her songs. Each one of those two books can be read independently of the present book, or of each other, though all three books, in their online versions as published in the last month of 2023, are provided with cross-references by way of links. The links keep track of the rewritten as well as the original online content of each essay assembled in the three books. The printed versions of all three books retain cross-references to the online content—though not by way of links.

Wherever I cross-refer from one book to another in this set of three books, my format for citation will be in short-hand: Sappho 0, Sappho I, Sappho II.

Introduction

0§1. What remains of the ancient text of songs attributed to Sappho is unfortunately most fragmentary. So, the research that has been done in modern times on her songmaking—on her poetics—is in its own way full of holes. My own relevant research is no exception, and I address in this book some of my concerns about the near-impossibility of aiming to paint a big picture of Sappho—a picture to be viewed by expert colleagues and non-experts alike. To symbolize such concerns, I choose as the featured image for this book here not an ancient painting—which is what I have done in the case of the book titled Sappho I—but a modern painting that can be viewed as a whimsical substitute for my own near-impossible big picture. That said, however, I need to proceed beyond such picturings from the modern or near-modern world and to catch at least a glimpse of what I call metaphorically the big picture of Sappho in the ancient world.

0§2. As I write this, I find that there continues to be much disagreement about Sappho in the academic world that I inhabit—disagreement about her, about her life and times, and even about her poetics. But there is room for more agreement, I think, about Sappho’s poetic language, and it is her language, in fact, that I hope to foreground in my approach to Sappho in this book. The approach I take is based primarily on linguistics, especially comparative linguistics. My early formation as an academic was in fact grounded in linguistics, not so much in “classical” studies—I use the word “classical” here in a narrow sense. That said, though, I must add that my later academic formation was in fact also shaped by classical studies in the broader sense of this same word “classical,” where the classics of ancient Greece and Rome can be compared with the classics of other traditional worlds. In my case, most of my comparative research in studying classical languages writ large involved, on the one hand in Greek, the poetic language of Homer and Sappho, especially as exemplified in the Homeric Iliad and in Song 44 of Sappho, and, on the other hand in Indic, the poetic language of the Rig-Veda, a body of hymns composed in the most ancient attested form of Sanskrit. A prime example of this research is a book of mine, originally published in 1974, titled Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic meter. That book, as we will see, turns out to be foundational for my overall argumentation here in this book Sappho 0, published in 2024. As this Introduction proceeds, I hope to situate more precisely the importance, for me, of such comparanda.

0§3. In analyzing the poetic language of Sappho, I engage in two kinds of reconstruction—both backward in time and forward in time. The first kind is so obvious that there seems at first to be no real need for any definition. An expected kind of definition, in any case, would be something like this: when we reconstruct any structure backward in time, our aim is to recover the original of that structure, which is expected to exist at ground zero. As for reconstructing forward in time, on the other hand, the aim is to trace the evolution of the given structure by starting from the original and working our way forward in time in order to see how the original structure survives in derivative structures.

0§4. But there is a big problem with both of these working definitions, and it centers on the very idea of a structure that is supposed to be original. In terms of comparative linguistic analysis, for example, the reconstructing of any given structure in language can go back in time only to earlier structures, without ever reaching, chronologically, an original structure—unless such a structure can be historically verified as a status quo.

0§5. Given that the reconstruction of Sappho’s poetic language backward in time cannot recover an absolute chronological ground zero, I am aware that my reconstructing forward in time is limited to a continuation from ground zero without actually starting at any datable “origin.”

0§6. As I noted at the outset, there remains much disagreement in the academic world about the poetics of Sappho and about Sappho herself. But there is considerable agreement, however hesitantly expressed, about assigning an approximate historical date for her reconstructed life and times. That date is generally understood to hover somewhere around 600 BCE——though the traditions of songmaking that made Sappho’s poetic language possible must surely be older, dating back far earlier—so much earlier that such traditions cannot even be traced back chronologically to any absolute point zero that could be verifiable.

0§7. That said, though, I take as a hypothetical given the general dating that is conventionally posited by most researchers in search of a historical Sappho, around 600 BCE, And I will focus on a place where my own reconstruction of Sappho’s songmaking could be historically contextualized. I save the details for later, but I anticipate the essentials already here. The place I have in mind can best be described as a ‘middle ground’—which is actually the meaning of an ancient Greek place-name, Messon. In Modern Greek, the name that the local population today give to the same place is Mesa. This place is situated at the center of the island known as Lesbos in ancient Greek—or Lesvos in Modern Greek. In ancient times, there existed at Messon a precinct that was sacred to the gods, and this precinct was a place where songs of Sappho were in those ancient times sung—as well as danced. What I just said is not just a claim. As I will argue in this book, it is a fact. That is to say, there is historical and even archaeological evidence for arguing that the sacred precinct of Messon was in ancient times a venue for the performances of Sappho’s songs.

0§8. In making such an argument, I have drawn on three old essays of mine, previously published online as well as in print, where I delved into the historical context of Messon as a venue for the singing—and dancing—of Sappho’s songs. I list here the three essays in the chronological order of the original publications:

#A. 2007. “Lyric and Greek Myth.” https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-lyric-and-greek-myth/.

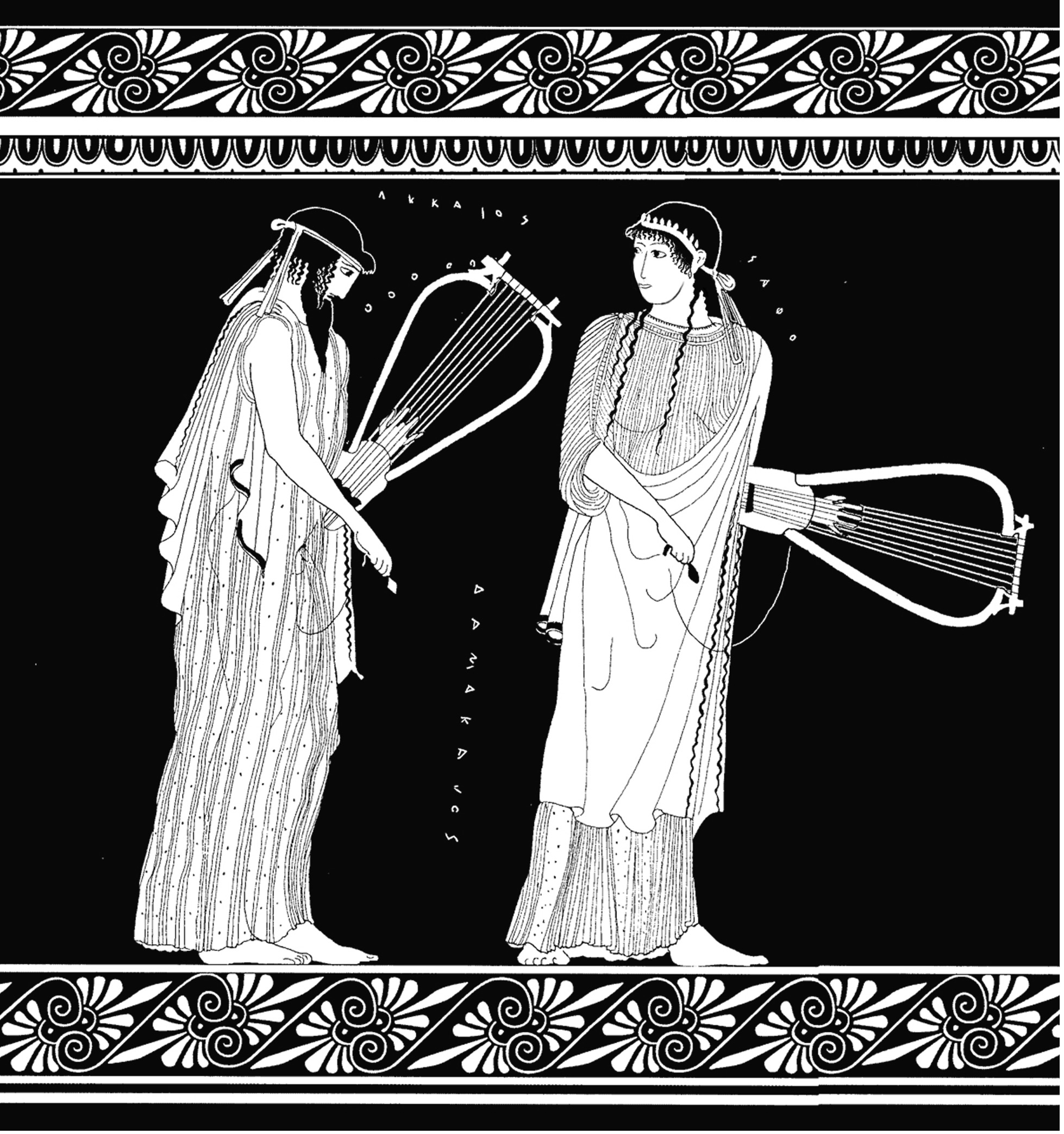

#B. 2007/2009. “Did Sappho and Alcaeus ever meet? Symmetries of myth and ritual in performing the songs of ancient Lesbos.” https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-did-sappho-and-alcaeus-ever-meet-symmetries-of-myth-and-ritual-in-performing-the-songs-of-ancient-lesbos/.

#C. 2015. “A poetics of sisterly affect in the Brothers Song and in other songs of Sappho.” https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-a-poetics-of-sisterly-affect-in-the-brothers-song-and-in-other-songs-of-sappho/.

The links to these three essays point to old and by now archived open-access online versions that have all been superannuated. All three of these old essays have now been rewritten and absorbed into my new book here, Sappho 0. The essays #A and #B and #C are now rewritten here as Essays One/Two amd Essay Three and Essay Four respectively. For reasons that I will explain presently, I have split my old essay #A into Essay One and Essay Two.

0§9. In the original versions of my essays #A and #B and #C, I found that the specific context of Messon in Lesbos was an ideal point of departure for my reconstrucing the overall context of Sappho’s songmaking. In my reshaping of these essays for Sappho 0, however, I now prefer to build gradations into my presentation, starting from basic descriptions and then proceeding to detailed analysis. In the course of reading Sappho 0, the reader will find that the context of Messon will be studied in progressively deeper detail.

0§10. Moreover, Sappho’s songmaking needs to be studied not only in the specific context of Messon but also in the general context of the overall poetic traditions that shaped such songmaking. At the start, I referred to such general context as the “big picture.” In the rewritten versions of the old essays #A and #B and #C, now absorbed as new Essays One and Two and Three and Four into Sappho 0 , I hope to provide such general context.

0§11. Next, I turn to introducing Essays Five, Six, and Seven. By way of introduction, I need to start with some further bibilographical background. Between February 2015 and February 2017, I produced a series of twenty-three studies related directly or indirectly to my attempts at recovering the big picture, as I have called it, of Sappho’s songmaking. I make a list here, in chronological order of publication:

#1. 2015.02.27. “Song 44 of Sappho and the Role of Women in the Making of Epic.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/song-44-of-sappho-and-the-role-of-women-in-the-making-of-epic/.

#2. 2015.06.01. “Herodotus and a courtesan from Naucratis.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/herodotus-and-a-courtesan-from-naucratis/.

#3. 2015.06.10. “Previewing a concise inventory of Greek etymologies, Part 3.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/previewing-a-concise-inventory-of-greek-etymologies-part-3/.

#4. 2015.07.01. “A sampling of comments on Iliad Rhapsody 2.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-iliad-scroll-2/.

#5. 2015.07.08. “Sappho’s ‘fire under the skin’ and the erotic syntax of an epigram by Posidippus.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/sapphos-fire-under-the-skin-and-the-erotic-syntax-of-an-epigram-by-posidippus/.

#6. 2015.08.26. “A sampling of comments on Iliad Rhapsody 9.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-iliad-rhapsody-9/.

#7. 2015.09.07. “Some ‘anchor comments’ on an ‘Aeolian’ Homer.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/some-anchor-comments-on-an-aeolian-homer/.

#8. 2015.10.01. “Genre, Occasion, and Choral Mimesis Revisited—with special reference to the ‘newest Sappho’.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/genre-occasion-and-choral-mimesis-revisited-with-special-reference-to-the-newest-sappho/.

#9. 2015.10.08. “The ‘Newest Sappho’: a set of working translations, with minimal comments.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-newest-sappho-a-set-of-working-translations-with-minimal-comments/.

#10. 2015.10.09. “An experiment in combining visual art with translations of Sappho.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/an-experiment-in-combining-visual-art-with-translations-of-sappho/.

#11. 2015.10.22. “Diachronic Sappho: some prolegomena.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/diachronic-sappho-some-prolegomena-2/.

#12. 2015.11.05. “Once again this time in Song 1 of Sappho.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/once-again-this-time-in-song-1-of-sappho/.

#13. 2015.11.09. “An experiment in combining visual art with translations of Sappho, Part 2.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/an-experiment-in-combining-visual-art-with-translations-of-sappho-part-2/.

#14. 2015.11.12. “The Tithonos Song of Sappho.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/the-tithonos-song-of-sappho/.

#15. 2015.11.19. “Echoes of Sappho in two epigrams of Posidippus.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/echoes-of-sappho-in-two-epigrams-of-posidippus/.

#16. 2015.12.01. “A sampling of comments on Iliad Rhapsody 19.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-iliad-rhapsody-19/.

#17. 2015.12.03. “Girl, interrupted: more about echoes of Sappho in Epigram 55 of Posidippus.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/girl-interrupted-more-about-echoes-of-sappho-in-epigram-55-of-posidippus/.

#18. 2015.12.31. “Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/some-imitations-of-pindar-and-sappho-by-horace/.

#19. 2016.01.07. “Weaving while singing Sappho’s songs in Epigram 55 of Posidippus.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/weaving-while-singing-sapphos-songs-in-epigram-55-of-posidippus/.

#20. 2016.08.31. “Song 44 of Sappho revisited: what is ‘oral’ about the text of this song?” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/song-44-of-sappho-revisited-what-is-oral-about-the-text-of-this-song/.

#21. 2016.10.08. “Sappho and mythmaking in the context of an Aeolian-Ionian poetic Sprachbund.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/sappho-and-mythmaking-in-the-context-of-an-aeolian-ionian-poetic-sprachbund/.

#22. 2017.02.17. “Sappho in the role of leader.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/sappho-in-the-role-of-leader/.

#23. 2017.02.23. “Sappho, once again this time.” https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/sappho-once-again-this-time/.

0§12. As in the case of the three lengthy studies that I listed earlier as ##ABC, the links to these twenty-three further studies have been provided here, and, once again, the links point to older open-access online versions. Like the lengthy essays ##ABC, some of these studies ##1–23 have been rewritten here in Sappho 0. An example of such rewritings is the essay at the end of the list, #23, which has been rewritten and absorbed into the Introduction here to Sappho 0. The content of some of the other studies has likewise been rewritten and absorbed into Sappho 0: notable examples are ##1, 20, 21: the first two of these studies—#1 and #20—have been consolidated into Essay Five of Sappho 0 here, and the third—#21—into Essay Six. Still others of these twenty-three studies have been rewritten and absorbed not into Sappho 0 here but into Sappho I. Those studies are numbered here as ## 5, 8, 11, 12, 14, 15, 17, 19.

0§13. As for the studies numbered #9 and #11, the working translations included there have also been reworked and incorporated into Sappho 0. While #9 featured my translations of the “newest” fragments, I produced in #11 my translations of the best-known “old” fragments of Sappho. Besides Song 1 as rendered in #11, I translated also Songs 16, 31, and 44. For both the “newest” and the “old” texts, my translations were occasionally enhanced by way of simultaneous visual narratives, the artistic creations of Glynnis Fawkes, who works in the style of graphic novels; previews of such visual narratives for the “old” and the “newest” texts can be viewed in the archived versions of #10 and #13 respectively.

0§14. The book titled Sappho I also includes rewritings of essays on Sappho that appeared online after February 2019, and the list of those online versions is tracked in the Bibliography for that book. As for the book titled Sappho II, it includes rewritings of further online essays on Sappho, likewise published after February 2019, and, in the Bibliography for that volume as well, I track there a list of those further online versions.

0§15. I sum up what I have surveyed so far. By contrast with Sappho I and Sappho II, the essays in Sappho 0 are all rewritings of work published earlier, starting in 2007. By now I have aready accounted for six of the seven essays rewritten in Sappho 0:

Essay 1, from the first part of #A1: 2007

Essay 2, from the second part of #A1: 2007

Essay 3, from #B: 2007/2009

Essay 4, from #C: 2015

Essay 5, from #1 combined with #20: 2015.02.27 combined with 2016.08.31

Essay 6, from #21: 2016.10.08

0§16. As for Essay Seven, which is a brief epilogue, I offer not a rewriting but a small set of reflections about even earlier studies of mine on Sappho, especially about a publication that goes all the way back to 1974.

0§17. Before I can say more about that publication, I need to note in general that I cite in Sappho 0 many studies of mine on Sappho that date back to the years 1973 through 2006. Throughout Sappho 0, I will be tracking, with some frequency, further details that can be found in such earlier studies. For the record, I list twelve relevant studies here, in chronological order:

GIM 1974, Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic Meter, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-comparative-studies-in-greek-and-indic-meter/.

BA 1979/1999, The Best of the Achaeans, https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-the-epic-hero/.

PH 1990a, Pindar’s Homer, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-pindars-homer-the-lyric-possession-of-an-epic-past/.

GMP 1990b, Greek Mythology and Poetics, https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/greek-mythology-and-poetics/. In this book, Chapter 9, is a rewriting of an essay originally published in 1973: “Phaethon, Sappho’s Phaon, and the White Rock of Leukas,” listed in the Bibliography for Sappho 0 here.

PP 1996a, Poetry as Performance, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-poetry-as-performance-homer-and-beyond/.

HQ 1996b, Homeric Questions, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-homeric-questions/.

HR 2003, Homeric Responses, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-homeric-responses/.

EH 2006, “The Epic Hero,” https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-the-epic-hero/.

HC 2009|2008, Homer the Classic, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-homer-the-classic/.

HPC 2010|2009, Homer the Preclassic, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-homer-the-preclassic/.

H24H 2013, The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-the-ancient-greek-hero-in-24-hours/.

MoM=2015, Masterpieces of Metonymy, https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-masterpieces-of-metonymy-from-ancient-greek-times-to-now/.

The ordering of this list is chronological, except that I date here as 1990 one particular essay that really goes back to 1973 in its original form before it was rewritten in 1990 as part of the book GMP = Greek Mythology and Poetics.

0§18. I cite many of these studies in Sappho 0, but the one study that is by far the most relevant to my overall argumentation is the very first on my list. It is a study that I have already foregrounded, abbreviated here as GIM = Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic Meter, originally published in 1974. That year, if I may engage here in a playful way of saying things, was my own personal ground zero in my efforts to reconstruct the poetic language of Sappho, culminating in Sappho 0, a book published half a century later. In the concluding Essay Seven of Sappho 0, I write a brief epilogue centering on Chapter 5 of that book on Greek and Indic meter, where I had dwelled on the deep antiquity of Sappho’s poetic language as evidenced in her Song 44, about the wedding of Hector and Andromache.

0§19. That chapter in a book dating all the way back to 1974 is relevant, however, not only to Essay 7 in Sappho 0. It is relevant to all seven essays in the book, especially to Essay One and Essay Two as also to Essay Five and Essay Six. So, concluding this Introduction while anticipating what I have to say in Essay One and Essay Two, I need to stress the importance, for me, of connecting my reconstruction of Sappho’s poetic language in Chapter 5 of Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic Meter with the cumulative synthesis of my overall arguments about Sappho.

0§20. In rewriting my old essay #A, as listed at 0§8 my Introduction here, I have split that essay, as noted already, into two new consecutive essays, Essay One and Essay Two. Essay One, as we will see, presents general background about the medium of “lyric” in the archaic period of ancient Greek song culture—that is, in the era of Sappho as also of her male poetic contemporary, a figure by the name of Alcaeus. And then, Essay Two presents specific background about the era of Sappho and Alcaeus. In Essays One and Two, I write no endnotes, by contrast with Essay Three and Essay Four. That is because I intend for the progression of my argumentation to be gradual. In the first two essays, I provide relatively less detail in bibliographical references, even to primary sources. For citations of the transmitted texts of poetry attributed to both Sappho and Alcaeus, I follow the streamlined edition of Campbell 1982, whose numbering of fragments [F] and testimonia [T] matches, for the most part, the numbering in the far more detailed older editions of Lobel/Page 1955 and Voigt 1971. Then, in Essay Three and Essay Four of Sappho 0, I follow up with more detailed argumentation of my own, backed up with copious endnotes, in a massive reworking of the old essays #B and #C, as listed at 0§8. And I supplement such content with further content that I have extracted from the old and by now archived versions of online essays that I have listed at 0§11: ##1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 7, 9, 16, 18, 20, 21. In the case of the essays #1 #20, #21, as I already noted, I have converted #1 and #20 into Essay Five and #21 into Essay Six. Then and only then do I finally arrive at an Epilogue, in Essay Seven.

Essay One. A cumulative synthesis of the arguments in this book about the the era of Sappho, Part I

1§2. There is a lack of precision in the general use of the term lyric. It is commonly associated with a variety of assumptions regarding the historical emergence of a “subjective I,” as represented by the individual poet of lyric, who is to be contrasted with the generic poet of epic, imagined as earlier and thus somehow less advanced. By extension, the subjective I is thought to be symptomatic of emerging notions of authorship. Such assumptions, as I will consistently argue in this book, cannot be sustained.

1§3. Lyric did not start in the archaic period. It is just as old as epic, which clearly predates the archaic period. And the traditions of lyric, like those of epic, were rooted in oral poetry, which is a matter of performance as well as composition (Lord 1995:22–68, “Oral Traditional Lyric Poetry”).

1§4. These two aspects of oral poetry, composition and performance, are interactive, and this interaction is parallel to the interaction of myth and ritual. In oral poetry, the performing of a composition is an activating of myth, and such activation is fundamentally a matter of ritual (Nagy 1994/1995a).

1§5. During the archaic period, the artistic production of lyric involved performance as well as composition. The performance was executed {19|20} either by a single performer or by a group that was actually or at least notionally participating in the performance. The most prominent Greek word referring to such a group is khoros ‘chorus’, which designates not just singing, like its derivative chorus in English, but dancing as well. Choral lyric could be sung and danced, or just sung or just danced. To be contrasted is monody, which means ‘solo singing’.

1§6. Lyric could be sung to the accompaniment of a string instrument, ordinarily the kitharā, which is conventionally translated in English as ‘lyre’. This English noun lyre and its adjective lyric are derived from lurā (lyra), which is another Greek word for a string instrument. Lyric could also be sung to the accompaniment of a wind instrument, ordinarily the aulos ‘reed’. Either way, whether the accompaniment took the form of string or wind instruments, a more precise term for such lyric is melic, derived from the Greek noun melos ‘song’. English melody is derived from Greek melōidiā, which means ‘the singing of melos’.

1§7. Lyric could also be sung without instrumental accompaniment. In some forms of unaccompanied lyric, the melody was reduced and the rhythm became more regulated than the rhythm of melic. In describing the rhythm of these forms of unaccompanied lyric, it is more accurate to use the term meter. And, in describing the performance of this kind of lyric, it is more accurate to speak of reciting instead of singing. Recited poetry is typified by three meters in particular: dactylic hexameter, elegiac couplet, and iambic trimeter. In ancient Greek poetic traditions, the dactylic hexameter became the sole medium of epic. As a poetic form, then, epic is far more specialized than lyric (PH 17–25, 47–51 = 1§§1–16, 55–64).

1§8. In the classical period, the solo performance of lyric poetry, both melic and non-melic, became highly professionalized. Lyric poetry was sung by professional soloists—either kitharōidoi ‘citharodes’ (= ‘kithara-singers’) or aulōidoi ‘aulodes’ (= ‘aulos-singers’), while non-lyric poetry was recited by professional soloists called rhapsōidoi ‘rhapsodes’. The solo performance of lyric poetry was monody. In the classical period, an era that is defined primarily by the city-state of Athens, the main occasion for citharodic or aulodic or rhapsodic solo performance was the festival of the Panathenaia, which was the context of competitions called mousikoi agōnes ‘musical contests’. These Panathenaic agōnes ‘contests’ were mousikoi ‘musical’ only in the sense that they were linked with the goddesses of poetic memory, the Muses (HC 360–373 = 3§23–46). They were not ‘musical’ in the modern sense, since the contests featured epic as well as lyric poetry. In the classical period of Athens, the epic repertoire was eventually restricted to the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey, competitively performed by rhapsodes, {20|21} while the lyric repertoire was restricted to songs competitively performed by citharodes and aulodes.

1§9. In the same classical period of Athens, lyric was also sung and danced by non-professional choruses. The primary occasion for such performances was the festival of the City Dionysia, the official venue of Athenian State Theater. The actors who delivered their lines by reciting the verses of non-melic poetry embedded in the dramas of Athenian State Theater were professionals, but the choruses who sang and danced the melic poetry also embedded in these dramas were non-professional, recruited from the body politic of citizens; theatrical choruses became professionalized only after the classical period, toward the end of the fourth century BCE (PP 157, 172–176).

1§10. The performances of non-professional choruses in Athenian State Theater represent an essential aspect of melic poetry that transcends the classical period. Not only in Athens but throughout the Greek-speaking world of the classical period and beyond, the most authoritative context of melic poetry was choral performance. The khoros ‘chorus’ was in fact a basic social reality in all phases of archaic Greek prehistory and history, and this reality was essential in the evolution of lyric during these earlier phases (Calame 2001).

1§11. An important differentiation becomes evident in the course of this evolution. It is an emerging split between the composer and the performer of lyric. Before this split, the authorship of any lyric composition was closely linked to the authority of lyric performance. This authority played itself out in a dramatized relationship between the khoros ‘chorus’ and a highlighted khorēgos ‘leader of the chorus’, as idealized in the relationship of the Muses as divine chorus to Apollo as their divine choral leader (PH 350–351 = 12§29). In lyric, as I argue, such authority is linked to the articulation of myth itself.

1§12. The khoros, as an institution, was considered the most authoritative medium not only for the performance of lyric composition but also for its transmission in the archaic period. As we see from the wording of choral lyric poetry, the poet’s voice is transmitted and notionally perpetuated by the seasonally recurring choral performances of his or her poetry. A most prominent example is Song 1 of Alcman (PH 345–346 = 12§18). The voices of the performers who sing and dance such poetry can even speak of the poet by name in the third person, identifying the poet as the one who composed their song. An example is Song 39 of Alcman. In other situations, the choral lyric composer speaks in the first person by borrowing, as it were, the voices of those who sing and dance in the composer’s {21|22} choral compositions. In Song 26 of Alcman, for example, the speaker declares that he is too old and weak to dance with the chorus of women who sing and dance his song: by implication, he continues to sing as their lead singer (PH 352–353 = 12§32).

1§13. For an understanding of authority and authorship in lyric poetry, more needs to be said about the actual transmission of lyric from the archaic into the classical period. The lyric traditions of the archaic period became an integral part of liberal education for the elites of the classical period. In leading cities like Athens, the young were educated by professionals in the non-professional singing, dancing, and reciting of songs that stemmed from the archaic period—songs that had become the classics of the classical period. As we see in the Clouds of Aristophanes (1355–1356), a young man who had the benefit of such an education could be expected to perform the artistic feat of singing solo a choral song composed by the archaic poet Simonides (F 507) while accompanying himself on the lyre. Elsewhere in the Clouds (967), we see a similar reference to a similar solo performance of a choral song composed by the even more archaic poet Stesichorus (F 274).

1§14. Among the elites of the classical period, the primary venue for the non-professional performance of archaic lyric songs that youths learned through such a liberal education was the sumposion ‘symposium’. Like the chorus, the symposium was a basic social reality in all phases of archaic Greek prehistory and history. And, like the chorus, it was a venue for the non-professional performance of lyric in all its forms.

1§15. The poets of lyric in the archaic period became the models for performing lyric in the classical period. And, as models, these figures became part of a canon of melic poets (Wilamowitz 1900:63–71). This canon, as it evolved from the archaic into the classical period and beyond, was composed of the following nine figures: Sappho, Alcaeus, Anacreon, Alcman, Stesichorus, Ibycus, Simonides, Pindar, Bacchylides. To this canonical grouping we may add a tenth figure, Corinna, although her status as a member of the canon was a matter of dispute in the postclassical period (PH 83 = 3§2n3). Other figures can be classified as authors of non-melic poetry: they include Archilochus, Callinus, Hipponax, Mimnermus, Theognis, Tyrtaeus, Semonides, Solon, and Xenophanes.

1§16. One of these figures, Xenophanes, can be classified in other ways as well. He is one of the so-called “pre-Socratic” thinkers whose thinking is attested primarily in the form of poetry. Two other such figures are Empedocles and Parmenides. Since the extant poetry of Xenophanes is composed in elegiac couplets, he belongs technically to the overall category of lyric poetry, whereas Empedocles and Parmenides do not, {22|23} since their extant poetry is composed in dactylic hexameters, which is the medium of epic.

1§17. Such taxonomies are imprecise in any case. A case in point is Simonides, whose attested compositions include non-melic poetry (like the Plataea Elegy, F 11 W2) as well as melic poetry. Simonides is credited with the composition of epigrams as well (Epigrammata I–LXXXIX, ed. Page). Conversely, the poetry of Sappho was evidently not restricted to melic: she is credited with the composition of elegiac couplets, iambic trimeters, and even epigrammatic dactylic hexameters (T 2; F 157–159D). A comparable phenomenon in the archaic period is the perception of Homer as an epigrammatist (as in the Herodotean Life of Homer 133–140 ed. Allen; HPC 48 = I§§117–119).

1§18. On the basis of what we have seen so far, it is clear that a given lyric composition could be sung or recited, instrumentally accompanied or not accompanied, and danced or not danced. It could be performed solo or in ensemble. Evidently, all these variables contributed to a wide variety of genres, but the actual categories of these genres are in general difficult to determine (Harvey 1955). Moreover, the categories as formulated in the postclassical period and thereafter may be in some respects artificial (Davies 1988). Such difficulties can be traced back to the fact that the actual writing down of archaic lyric poetry blurs whatever we may know about the occasion or occasions of performance. The genres of lyric poetry stem ultimately from such occasions (Nagy 1994/1995a).

1§19. In the postclassical period, antiquarians lost interest in finding out about occasions for performance, and they assumed for the most part that poets in the archaic period composed by way of writing. For example, Pausanias (7.20.4) says that Alcaeus wrote (graphein) his Hymn to Hermes (F 308c). A similar assumption is made about Homer himself: Pausanias (3.24.11, 8.29.2) thinks of Homer as an author who wrote (graphein) his poetry.

1§20. In the classical period, by contrast, the making of poetry by the grand poets of the past was not equated with the act of writing (HPC 31 = I§61). As we see from the wording of Plato, for example (Phaedo 94d, Hippias Minor 371a, Republic 2.378d, Ion 531c–d), Homer is consistently pictured as a poet who ‘makes’ (poieîn) his poetry, not as one who ‘writes’ (graphein) it. So also Herodotus says that Homer and Hesiod ‘make’ (poieîn) what they say in poetry (2.53.2); and he says elsewhere that Alcaeus ‘makes’ (poieîn) his poetry (5.95).

1§21. In any case, the basic fact remains that the composition of poetry in the archaic period came to life in performance, not in the reading of {23|24} something that was written. Accordingly, the occasions of performance need to be studied in their historical contexts.

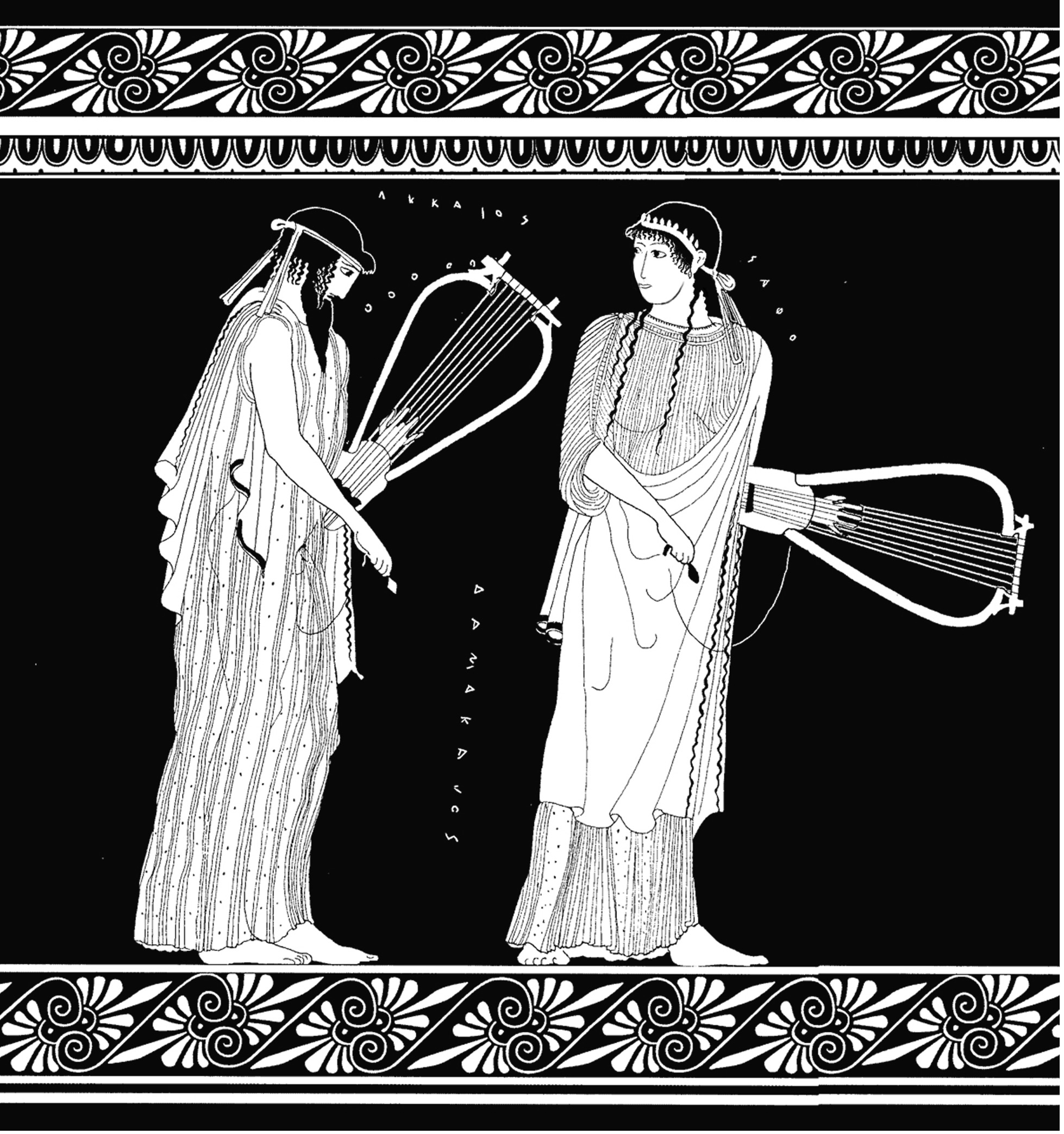

Essay Two. A cumulative synthesis of the arguments in this book about the the era of Sappho, Part II

2§7. In Song 96 of Sappho, such performance tuide ‘here’ (line 2) within the common choral ground of Lesbos is being nostalgically contrasted with the choral performance of a missing prima donna who is imagined as performing somewhere else at that same moment: she is now in an alien choral ground, as the prima donna of ‘Lydian women’ who are singing and dancing in the moonlight (lines 4–9). The wording here refers to a seasonally recurring choral event known as the ‘Dance of the Lydian {25|26} Maidens’, performed by the local women of the Ionian city of Ephesus at a grand festival held in their own sacred place of singing and dancing (PH 298–299 = 10§31). There are comparable ‘Lydian’ themes embedded in the seasonally recurring choral festivities of Sparta: one such event was known as the ‘Procession of the Lydians’ (Plutarch Life of Aristides 17.10). And just as Sappho’s Song 96 represents the ‘Lydian’ women as singing and dancing their choral song in a moonlit setting (lines 4–9), so too are the women of Lesbos singing and dancing their own choral song tuide or ‘here’ (line 2). There is a comparable setting in Song 154 of Sappho, where we see women pictured as poised to sing and dance around a bōmos ‘altar’ (line 2).

2§8. There is another such reference to the common choral ground of Lesbos, as marked by the deictic word tuide ‘here’, at line 5 in Song 1 of Sappho:, which is arguably her most celebrated song:

|1 ποικιλόθρον’ ἀθανάτἈφρόδιτα, |2 παῖ Δίοc δολόπλοκε, λίϲϲομαί ϲε, |3 μή μ’ ἄϲαιϲι μηδ’ ὀνίαιϲι δάμνα, |4 πότνια, θῦμον,

|5 ἀλλὰ τυίδ’ ἔλθ’, αἴ ποτα κἀτέρωτα |6 τὰc ἔμαc αὔδαc ἀίοιϲα πήλοι |7 ἔκλυεc, πάτροc δὲ δόμον λίποιϲα |8 χρύϲιον ἦλθεc

|9 ἄρμ’ ὐπαϲδεύξαιϲα· κάλοι δέ ϲ’ ἆγον |10 ὤκεεc ϲτροῦθοι περὶ γᾶc μελαίναc |11 πύκνα δίννεντεc πτέρ’ ἀπ’ ὠράνωἴθε|12ροc διὰ μέϲϲω·

|13 αἶψα δ’ ἐξίκοντο· ϲὺ δ’, ὦ μάκαιρα, |14 μειδιαίϲαιϲ’ ἀθανάτωι προϲώπωι |15 ἤρε’ ὄττι δηὖτε πέπονθα κὤττι |16 δηὖτε κάλημμι

|17 κὤττι μοι μάλιϲτα θέλω γένεϲθαι |18 μαινόλαι θύμωι· τίνα δηὖτε πείθω |19 βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα; τίc ϲ’, ὦ |20 Ψάπφ’, ἀδικήει;

|21 καὶ γὰρ αἰ φεύγει, ταχέωc διώξει, |22 αἰ δὲ δῶρα μὴ δέκετ’, ἀλλὰ δώϲει, |23 αἰ δὲ μὴ φίλει, ταχέωc φιλήϲει |24 κωὐκ ἐθέλοιϲα.

|25 ἔλθε μοι καὶ νῦν, χαλέπαν δὲ λῦϲον |26 ἐκ μερίμναν, ὄϲϲα δέ μοι τέλεϲϲαι |27 θῦμοc ἰμέρρει, τέλεϲον, ϲὺ δ’ αὔτα |28ϲύμμαχοc ἔϲϲο.

[Note on line 19: I follow the reading βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην as restored by Parca 1982.]

stanza 1||1 You with pattern-woven flowers, immortal Aphrodite, |2 child of Zeus, weaver of wiles, I implore you, |3 do not dominate with hurts and pains, |4 Mistress, my heart!

stanza 2||5 But come here [tuide], if ever at any other time |6 hearing my voice from afar, |7 you heeded me, and leaving the palace of your father, |8 golden, you came,

stanza 3||9 having harnessed the chariot; and you were carried along by beautiful |10 swift sparrows over the dark earth |11swirling with their dense plumage from the sky through the |12 midst of the aether,

stanza 4||13 and straightaway they arrived. But you, O holy one, |14 smiling with your immortal looks, |15 kept asking what is it once again this time [dēute] that has happened to me and for what reason |16 once again this time [dēute] do I invoke you,

stanza 5||17 and what is it that I want more than anything to happen |18 to my frenzied [mainolās] heart [thūmos]? “Whom am I once again this time [dēute] to persuade, |19 setting out to bring [agein] her to your love? Who is doing you, |20Sappho, wrong?

stanza 6||21 For if she is fleeing now, soon she will be pursuing. |22 If she is not taking gifts, soon she will be giving them. |23 If she does not love, soon she will love |24 even against her will.”

stanza 7||25 Come to me even now, and free me from harsh |26 anxieties, and however many things |27 my heart [thūmos] yearns to get done, you do for me. You |28 become my ally in war.

Song 1 of Sappho = Prayer to Aphrodite

2§9. As we will see in due course, Sappho is being pictured tuide ‘here’ as the lead singer of a choral performance. She leads off by praying to Aphrodite to be present, that is, to manifest herself ‘here’, in an epiphany. The goddess is invoked from far away in the sky, which is separated from the earth by the immeasurably vast space of ‘aether’. Despite this overwhelming sense of separation, Aphrodite makes her presence felt immediately, once she is invoked. The goddess appears, that is, she is now present ‘here’ in the sacred space of performance, and her presence ‘here’ becomes an epiphany for all those who are present. Then, once Aphrodite is present, she exchanges roles with the prima donna who figures as the leader of choral performance. In the part of Song 1 that we see enclosed within quotation marks in the visual formatting of modern editions (lines 18–24), the first-person ‘I’ of Sappho is now replaced by Aphrodite herself, who has been a second-person ‘you’ up to this point. We see here an exchange of roles between the first-person ‘I’ and the second-person ‘you’. The first-person ‘I’ now becomes Aphrodite, who proceeds to speak in the performing voice of Sappho to Sappho herself, who in turn has now become the second-person ‘you’. During Aphrodite’s epiphany inside the shared sacred space of the people of Lesbos, a fusion of identities takes place between the goddess and the prima donna who leads the choral performance ‘here’, that is, in this sacred space (PP 97–103).

2§16. Typical of such contact with divinity is this celebrated wedding song of Sappho:

|1 φαίνεταί μοι κῆνος ἴσος θέοισιν |2 ἔμμεν’ ὤνηρ, ὄττις ἐνάντιός τοι |3 ἰσδάνει καὶ πλάσιον ἆδυ φωνεί-|4 σας ὐπακούει |5καὶ γελαίσας ἰμέροεν, τό μ’ ἦ μὰν |6 καρδίαν ἐν στήθεσιν ἐπτόαισεν, |7 ὠς γὰρ ἔς σ’ ἴδω βρόχε’ ὤς με φώναι-|8 σ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ἔτ’ εἴκει, |9 ἀλλὰ κὰμ μὲν γλῶσσα ἔαγε λέπτον |10 δ’ αὔτικα χρῶι πῦρ ὐπαδεδρόμηκεν, |11 ὀππάτεσσι δ’ οὐδ’ ἒν ὄρημμ’, ἐπιρρόμ-|12 βεισι δ’ ἄκουαι, |13 κάδ δέ μ’ ἴδρως κακχέεται τρόμος δὲ |14 παῖσαν ἄγρει, χλωροτέρα δὲ ποίας |15 ἔμμι, τεθνάκην δ’ ὀλίγω ’πιδεύης |16 φαίνομ’ ἔμ’ αὔται·

|1 He appears [phainetai] to me, that one, equal to the gods [īsos theoisin], |2 that man who, facing you |3 is seated and, up close, that sweet voice of yours |4 he listens to, |5 and how you laugh a laugh that brings desire. Why, it just |6 makes my heart flutter within my breast. |7 You see, the moment I look at you, right then, for me |8 to make any sound at all won’t work anymore. |9 My tongue has a breakdown and a delicate |10 —all of a sudden—fire rushes under my skin. |11 With my eyes I see not a thing, and there is a roar |12 my ears make. |13 Sweat pours down me and a trembling |14 seizes all of me; paler than grass |15 am I, and a little short of death |16 do I appear [phainomai] to myself.

Sappho Song 31

2§17. It is said here that the bridegroom phainetai ‘appears’ to be isos theoisin ‘equal to the gods’. Appearances become realities, however, since phainetai means not only ‘he appears’ but also ‘he is manifested in an epiphany’, and this epiphany is felt as real (PH 201 = 7§2n10). In the internal logic of this song, seeing the bridegroom as a god for a moment is just as real as seeing Sappho as a goddess for a moment in the logic of Song 1 of Sappho.

2§18. The sense of reality is evident in the wording we have just seen, phainetai moi kēnos isos theoisin | emmen’ ōnēr ‘he appears [phainetai] to me, that one, equal to the gods, | the man who …’. The first-person moi here in Song 31 of Sappho refers to the speaker, who is ‘Sappho’. In another song of Sappho, we find the wording phainetai woi kēnos isos theoisin ‘he appears [phainetai] to her, that one, equal to the gods’ (F 165). In that song, the third-person woi ‘to her’ may perhaps refer to the bride. Or perhaps the speaker of that wording is imagined as Aphrodite herself.

2§44. In compensation for his being cut down in the bloom of his youth, Achilles is destined to have a kleos ‘glory’ that is aphthiton ‘unwilting’: that is what the hero’s mother foretells for him, as Achilles himself is quoted as saying (Iliad 9.413). The word kleos expresses not only the idea of prestige as conveyed by the translation ‘glory’ but also the idea of a medium that confers this prestige (BA 15–18 = 1§§2–4). And this medium of kleos is not only epic, as represented by the Homeric Iliad, but also lyric, as best represented in the historical period by the poet Pindar. In the praise poetry of Pindar, the poet proudly proclaims his mastery of the prestige conferred by kleos (as in Nemean 7.61–63; PH 147 = 6§3). As for the word aphthiton ‘unwilting’, it is used as an epithet of kleos not only in epic but also in lyric, as we see from the songs of Sappho (F 44.4) and Ibycus (F 282.47). This epithet expresses the idea that the medium of kleos is a metaphorical flower that will never stop blossoming. In a song composed by Pindar (Isthmian 8.56a–62) the words of the poet declare that Achilles, who as we have seen is destined to be glorified by kleos, will die and will thus stop blossoming, that is, he will ‘wilt’, phthinein, but the medium that conveys the message of death will never wilt: that medium is pictured as a choral lyric song eternally sung by the Muses as they lament the beautiful wilted flower that is Achilles, the quintessential beau mort PH 204–206 = 7§6). This song of the Muses is parallel to the choral lyric song that is sung by Thetis accompanied by her fellow Nereids as they lament in the Iliad (18.54–60) the future death of her beloved son: here again, as we saw earlier, Achilles is figured as a beautiful seedling that is destined to wilt (BA 182–183 = 10§11); in the Odyssey (24.58–59, 60–62), we find a retrospective description of the lament sung by Thetis and her fellow Nereids at the actual funeral of Achilles, followed by the lament of the Muses themselves.

2§72. The ‘I’ of Alcaeus can act as the crazed lover of a young boy or girl. His ‘I’ can even be Sappho herself, transposed from the protective context of the chorus into the unprotected context of the symposium. Aristotle (Rhetoric 1.1367a) quotes the relevant wording of a duet featuring, on one side, Alcaeus in the act of making sly sexual advances on Sappho and, on the other side, Sappho in the act of trying to protect her honor by cleverly fending off the predatory words of Alcaeus. In Essay Three, I will go into detail about attested traditions of singing songs about erotic encounters where the roles of male and female speakers can even be sung by a soloist imitating a duet.

2§73. Such symmetry between Alcaeus and Sappho was perpetuated in the poetic traditions of the symposium well beyond the old historical setting of festive celebrations at Messon in Lesbos. A newer historical setting was Athens during the sixth and the fifth centuries BCE. Here the songs of Alcaeus and Sappho continued to be performed in two coexisting formats of monodic performance: one of these was the relatively small-scale and restricted format of the symposium, while the other was the spectacularly large-scale and public format of citharodic concerts at the musical competitions of the festival of the Panathenaia (Nagy 2004).

Essay Three. Did Sappho and Alcaeus Ever Meet?

3§0. This essay is rewritten from an earlier version, cited as #B 2007|2009 at 0§8 in the Introduction above. The original printed version appeared in Literatur und Religion I. Wege zu einer mythisch–rituellen Poetik bei den Griechen, ed. A. Bierl, R. Lämmle, K. Wesselmann; Basiliensia – MythosEikonPoiesis, vol. 1.1, 211–269. Berlin / New York 2007. The pagination of that version will be indicated here by way of “curly” brackets (“{“ and “}”). For example, “{211|212}” indicates where p. 211 of the printed article ends and p. 212 begins.

3§1. Myth and ritual tend to be segregated from one another in most studies of ancient Greek traditions.[1] A contributing cause is a general lack of sufficient internal evidence concerning the relationship of myth and ritual. Another contributing cause is a failure to consider the available comparative evidence. This situation has led to an overly narrow understanding of myth and ritual as concepts—and to the emergence of a false dichotomy between these two narrowed concepts. A sustained anthropological approach can help break down this dichotomy.[2] Applying such an approach, I have argued that myth is actually an aspect of ritual in situations where a given myth comes to life in performance—and where that performance counts as part of a ritual.[3] I propose to develop this argument further here by considering mythological themes evoked in singing the songs of Sappho and Alcaeus in various ritual contexts. I will focus on themes involving Aphrodite and Dionysus, which will be relevant to the question that I ask in the title: did Sappho and Alcaeus ever meet?[4]

3§2, As I write this, the very idea that the songs of Sappho and Alcaeus were sung in ritual contexts is not to be found in most standard works on these songs.[5] But there are telling examples of such contexts, two of which stand out. One is the khoros and the other is the kōmos.

3§3. I start with a working definition of the khoros: it is a group of male or female performers who sing and dance a given song within a space (real or notional) that is sacred to a divinity or to a constellation of divinities.[6] {211|212} In the case of Sappho, her songs were once performed by women singing and dancing within such a space.[7] And the divinity most closely identified with most of her songs is Aphrodite.[8]

3§4. I now proceed to a working definition of the kōmos: it is a group of male performers who sing and dance a given song on a festive occasion that calls for the drinking of wine.[9] The combination of wine and song expresses the ritual communion of those participating in the kōmos. This communion creates a bonding of the participants with one another and with the divinity who makes the communion sacred, that is, Dionysus.[10] To the extent that the kōmos is a group of male performers who sing and dance in a space (real or notional) that is sacred to Dionysus, it can be considered a subcategory of the khoros.

3§5. Back when Sappho is thought to have flourished in Lesbos, around 600 BCE, we expect that her songs would be performed by girls or women in the context of the khoros. Around the same time in Lesbos, the songs of Alcaeus would be performed by men in the context of the kōmos. This context is signaled by the use of the verb kōmazein ‘sing and dance in the kōmos’, which is actually attested in one of his songs (Alcaeus F 374.1).

3§6. There is an overlap, however, in performing the songs attributed to Sappho. As I will argue, such songs could be performed not only by girls or women in a khoros but also by men in a kōmos.

3§7. A typical context for the kōmos is the symposium.[11] Accordingly, at this early point in my argumentation, I find it convenient to use the general term sympotic in referring to the context of the kōmos. At a later point, however, I will need to use the more specific term comastic. That is because the ancient symposium, in all its attested varieties, could accommodate other kinds of singing and dancing besides the kinds we find attested for the kōmos.[12] {212|213}

3§8. For now there is one basic fact to keep in mind about the term sympotic. Dionysus is the god of the symposium. So the sympotic songs attributed to Alcaeus must be connected somehow to Dionysus. It is not enough to say, however, that Dionysus is the sympotic god. The essence of Dionysus is not only sympotic. It is also theatrical. As I noted already in Essay Two, Dionysus is also the god of theater. So, the question arises, how does the theatrical essence of Dionysus connect to the sympotic songs attributed to Alcaeus?

3§9. In search of an answer, I begin by focusing on the role of Dionysus as the presiding god of the festival of the City Dionysia in Athens. This festive occasion was the primary setting for Athenian State Theater.[13] Such a role of Dionysus as the presiding god of theater is parallel to his role as the presiding god of the symposium.[14] That is because the symposium of Dionysus, like the theater of Dionysus, was a festive occasion for the acting out of roles by way of song and dance.[15] And the Greek word that signals such a festive acting out of roles is mīmēsis.[16] In terms of this word, the sympotic Dionysus is simultaneously a mimetic Dionysus. In this sense, the songs of Alcaeus are not only sympotic: they are also mimetic and even quasi-theatrical.

3§10. As I have argued elsewhere, the songs of Alcaeus were once performed in a quasi-theatrical setting, visualized as a festive occasion that takes place in a sacred space set aside for festivals.[17] There once existed such a sacred space, shared by a confederation of cities located on the island of Lesbos. The confederation was headed by the city of Mytilene, which dominated the other cities on the island. And, as I noted already from the start in this book, the name of the federal sacred space shared by all these cities was Messon, which means ‘the middle space’. The exact location of Messon has been identified by Louis Robert, primarily on the basis of epigraphical evidence: ancient Messon was the same place that is known today as Mesa.[18] In the Greek language as spoken today, this name Mesa derives from the neuter plural of meson ‘middle’ just as the ancient name Messon derived from the neuter singular messon ‘middle’ (the double –ss– was characteristic of the ancient Aeolic {213|214} dialects of Lesbos). True to its name, this place Messon / Mesa is in fact located in the middle of the island.

3§11. Songs 129 and 130 of Alcaeus refer to Messon.[19] The wording of these songs describes this place as a temenos ‘sacred space’ that is xunon ‘common’ to all the people of Lesbos (F 129.1–3), and it is sacred to three divinities in particular: (1) Zeus, (2) an unnamed goddess who is evidently Hera, and (3) Dionysus (F 129.3–9).[20] Of particular interest is the epithet applied to Dionysus, ōmēstēs, which I translate not in the sense of active agency but, in an older sense, where the distinction between active and passive voice is neutralized: ‘having to do with the eating of raw flesh’ (F 129.9: Ζόννυσσον ὠμήσταν). As we will see later, this epithet is relevant to the myths and rituals of Dionysus in Lesbos.[21]

3§12. Given this background, I return to my question: how are the sympotic songs of Alcaeus mimetic and even quasi-theatrical? In these songs, there is a variety of roles acted out by the ‘I’ who figures as the speaker. The roles may be either integrated with or alienated from the community that is meant to hear the performances of these songs. Both the integration and the alienation may be expressed as simultaneously political and personal, and the personal feelings frequently show an erotic dimension—either positive or negative. Even in songs that dwell on feelings of alienation, however, the overall context is nevertheless one of integration. Alcaeus figures as a citizen of Mytilene who became alienated from his city in his own lifetime and was forced to take refuge in the federal sacred space called Messon—only to become notionally reintegrated with his community after he died, receiving the honors of a cult hero within this same sacred space.[22]

3§13. The combined evidence of Songs 129 and 130 of Alcaeus is most revealing in this regard. The speaker expresses his alienation as he tells about his exile from his native city of Mytilene (F 129.12; F 130.16–19, 23–27) and about his finding a place of refuge at Messon, described here as a no-man’s-land, eskhatiai, far removed from city life (F 130.24: φεύγων ἐσχατίαισ’). In this negative context, we see a place of alienation, and the speaker says he ‘abides’ there, oikeîn, all by himself (F 130.25: οἶος ἐοίκησα). On the other hand, this same place is where the speaker says the people of Lesbos celebrate their ‘reunions’, sunodoi (F 130.30: συνόδοισι). {214|215} In this positive context, we now see a place of integration, and the speaker goes on to say once again that he ‘abides’ there, oikeîn (F 130.31: οἴκημ<μ>ι). This place is Messon, which the words of Alcaeus describe as a temenos ‘sacred space’ that is xunon ‘common’ to all the people of Lesbos (F 129.2–3: τέμενος μέγα | ξῦνον). To be contrasted with this positive context is the negative context of this same temenos ‘sacred space’ (F 130.28: τέμ[ε]νος θέων): in this negative context, as we saw earlier, the words of Alcaeus describe this space as a lonely place where he ‘abides’, oikeîn, all by himself (F 130.25: οἶος ἐοίκησα). But this same lonely place is where the speaker says he encounters a chorus of beautiful young women in the act of singing and dancing (F 130.31–35). I repeat, this place is Messon, which the words of Alcaeus describe as a temenos ‘sacred space’ that is xunon ‘common’ to all the people of Lesbos (F 129.2–3: τέμενος μέγα | ξῦνον).[23]

3§14. Such sustained balancing between the themes of alienation and integration in this context of the temenos ‘sacred space’ at Messon points to an overarching pattern of integration, and a sign of this integration is the reference in Song 130 of Alcaeus to a chorus of beautiful young women shown in the act of singing and dancing. As I have argued in an earlier study, this reference is really a cross-reference to a form of choral performance that is typical of the songs of Sappho.[24] In terms of this argument, the temenos ‘sacred space’ at Messon was actually a setting for the performances of songs attributed not only to Alcaeus but also to Sappho.[25] That is, Sappho figures as a lead performer of choral song and dance at Messon.[26]

3§15. In brief, then, the sacred complex of Messon in Lesbos is the historical context for understanding the mimetic and even quasi-theatrical characteristics of the songs of Alcaeus, and the same can be said about the songs of Sappho.[27] {215|216}

3§16. While Alcaeus speaks as the lead singer of a kōmos, Sappho speaks as the lead singer of a khoros. This choral role of Sappho is ignored in many standard modern works on Sappho and Alcaeus.[28] In the songs of Sappho, the ‘I’ may represent a lead singer who can speak directly to a presiding divinity on behalf of the whole khoros, as we see in Song 1 of Sappho. Further, the ‘I’ may also represent that divinity speaking back to the lead singer and, by extension, to the whole group attending and participating in the performance of the song. Within the framework of that song, the lead singer becomes identified with Aphrodite by virtue of performing as the prima donna of a khoros. And there are also many other roles played out by the speaking ‘I’ in the songs of Sappho. For example the ‘I’ may be Sappho speaking in the first person to a bride or to a bridegroom in the second person—or about them in the third person.[29]

3§17. So also in the songs of Alcaeus, the ‘I’ may play out a variety of roles. Primarily, the ‘I’ is Alcaeus speaking in the first person to his comrades in the second person—or about them in the third person. Secondarily, however, the ‘I’ may play roles that are distinct from the persona of Alcaeus.[30]

3§18. From what we have seen so far, the sacred space of Messon was a stage, as it were, for not one but two kinds of quasi-theatrical performance: one kind was the sympotic performance of the songs of Alcaeus, while the other was the choral performance of the songs of Sappho.[31] {216|217}

3§19. With this observation in place, I have come to the end of my brief overview of the songs of Alcaeus as performed in contexts appropriate to a kōmos. So I have reached a point where I can begin my argumentation concerning an overlap with the songs of Sappho as performed in contexts appropriate to a khoros. I am now ready to argue that the songs of Sappho could be performed not only by women or girls in a khoros but also by men or boys in a kōmos.

3§20. To argue for such an overlap is to argue for a symmetry between the profane and the sacred in the songs of Alcaeus and Sappho, despite what appears at first to be a disconnectedness between these two sets of songs:

Behind the appearances of […] disconnectedness between the songs of Alcaeus and Sappho is a basic pattern of connectedness in both form and content. This pattern is a matter of symmetry. In archaic Greek poetry, symmetry is achieved by balancing two opposing members of a binary opposition, so that one member is marked and the other member is unmarked; while the marked member is exclusive of the unmarked, the unmarked member is inclusive of the marked, serving as the actual basis of inclusion. Such a description suits the working relationship between the profane and the sacred in the songs of Alcaeus and Sappho. What is sacred about these songs is the divine basis of their performance in a festive setting, that is, at festivals sacred to gods. What is profane about these songs is the human basis of what they express in that same setting. We see in these songs genuine expressions of human experiences, such as feelings of love, hate, anger, fear, pity, and so on. These experiences, though they are unmarked in everyday settings, are marked in festive settings. In other words, the symmetry of the profane and the sacred in the songs of Alcaeus and Sappho is a matter of balancing the profane as the marked member against the sacred as the unmarked member in their opposition to each other; while the profane is exclusive of the sacred, the sacred is inclusive of the profane, serving as the actual basis of inclusion.[32]

3§21. This formulation has a converse. Whereas the sacred includes the profane in festive situations, it can be expected to exclude the profane in non-festive situations. That is, in non-festive situations the sacred is marked and the profane is unmarked. Only in festive situations does the sacred become the unmarked member in its opposition with the profane. Only in festive situations does the sacred include the profane. Once the festival is over, the sacred can once again wall itself off from the profane.

3§22. The festive balancing of the sacred and the profane is relevant to questions of morality and decorum. Such questions are pointedly raised in {217|218} the sympotic songs of Alcaeus, which display morally incorrect as well as correct ways of speaking and behaving in general.[33] Despite such displays, however, the incorrect aspects of these songs remain subordinated to the overall moral correctness of the symposium as a festive ritual made sacred by the notional presence of the god Dionysus.[34]

3§23. An analogous observation can be made about vase paintings featuring the god of the symposium, Dionysus himself. Vase painters conventionally depict this god as a morally correct and decorous figure even in settings where his own closest attendants abandon themselves to morally incorrect and indecorous behavior. We find striking illustrations in pictures of satyrs, mythologized Dionysiac attendants whom vase painters conventionally depict in the act of committing various wanton sexual acts.[35] By contrast, such depictions generally show Dionysus himself in a different light: the god maintains a stance of decorum amidst all the indecorous wantonness of his attendants.[36]

3§24. Likewise in sympotic songs, we find a festive balance between the sacred and the profane, though the profanities seem to be less pronounced. To illustrate such balancing, I highlight the inclusion of songs typical of Sappho in sympotic songs sung by men and boys. A case in point is Song 2 of Sappho. We have two attested versions of the closure of this song. In the version inscribed on the so-called Florentine ostrakon dated to the third century BCE, at lines 13–16, the last word is οἰνοχόεισα ‘pouring wine’, referring to Aphrodite herself in the act of pouring not wine but nectar. In the “Attic” version of these lines as quoted by Athenaeus (11.463e), on the other hand, the wording after οἰνοχοοῦσα ‘pouring wine’ continues with τούτοις τοῖς ἑταίροις ἐμοῖς γε καὶ σοῖς ‘for these my (male) companions [hetairoi], such as they are, as well as for your {218|219} (male divine) companions [= Aphrodite’s]’.[37] At a later point in my argumentation, we will see that this kind of sympotic closure is compatible with the singing of Sappho’s songs by men and boys at Athenian symposia (Aelian via Stobaeus 3.29.58). As we will also see, choral songs typical of Sappho could be included in sympotic songs typical of Alcaeus.

3§25. Within the songs of Alcaeus, the choral figure of Sappho could appear decorous—even sacred. A notable example is this fragment:

ἰόπλοκ’ ἄγνα μελλιχόμειδε Σάπφοι

You with strands of hair in violet, O holy [(h)agna] one, you with the honey-sweet smile, O Sappho!

Alcaeus F 384

3§26. As I argued in Essay Two, the wording that describes the choral figure of Sappho here is fit for a queenly goddess.[38] For example, the epithet (h)agna ‘holy’ is elsewhere applied to the goddess Athena (Alcaeus F 298.17) and to the Kharites ‘Graces’ as goddesses (Sappho F 53.1, 103.8; Alcaeus F 386.1). As for the epithet ioplokos ‘with strands of hair [garlanded] in violet’, it is elsewhere applied as a generic epithet to the Muses themselves (Bacchylides 3.17). In the overall context of all her songs identifying her with Aphrodite herself, Sappho appears here as the very picture of that goddess.

3§27. Such appearances, however, can be deceiving. The aura of the sacred and the decorous as externalized in choral songs typical of Sappho can no longer be the same once these songs make contact with the profane and the indecorous as externalized in sympotic songs typical of Alcaeus. The dialogic personality of Sappho speaking in the protective context of songs sung by women or girls in a khoros ‘chorus’ will be endangered in the unprotected context of songs sung by men or boys in a symposium or, more specifically, in a Dionysiac kōmos. In such unprotected contexts, even the honor of Sappho as a proper woman will be called into question.

3§28. Such a situation arises in a fragment of poetry quoted by Aristotle (Rhetoric 1.1367a) and generally attributed to Sappho (F 137). The fragment reveals a dialogue in song—a duet, as it were. This musical dialogue features, on one side, Alcaeus in the act of making sly sexual advances on Sappho and, on the other side, Sappho in the act of trying to protect her honor by cleverly {219|220} fending off the predatory words of Alcaeus. Ancient scholia interpret Aristotle to mean that it was Sappho who composed this dialogue in song, and that the song is representing Alcaeus in the act of addressing her.[39] Modern experts tend to agree. [40] I will argue, however, for the opposite: that the notional composer of this dialogue in song was Alcaeus, and that the song is representing Sappho in the act of responding to him. Here is the dialogue as quoted by Aristotle:

τὰ γὰρ αἰσχρὰ αἰσχύνονται καὶ λέγοντες καὶ ποιοῦντες καὶ μέλλοντες, ὥσπερ καὶ Σαπφὼ πεποίηκεν, εἰπόντος τοῦ Ἀλκαίου

θέλω τι εἰπῆν, ἀλλά με κωλύει

αἰδώς,

αἰ δ’ ἦχες ἐσθλῶν ἵμερον ἢ καλῶν

καὶ μή τι εἰπῆν γλῶσσ’ ἐκύκα κακόν

αἰδώς κέν σε οὐκ εἶχεν ὄμματ’,

ἀλλ’ ἔλεγες περὶ τῶ δικαίω.

Men are ashamed to say, to do, or to intend to do shameful things. That is exactly the way Sappho composed her words when Alcaeus said:

{He:} I want to say something to you, but I am prevented by

shame [aidōs] …

{She:}But if you had a desire for good and beautiful things

and if your tongue were not stirring up something bad to say,

then shame would not seize your eyes

and you would be speaking about the just and honorable thing to do.

“Sappho” F 137 via the quotation of Aristotle Rhetoric 1.1367a

3§29. The meter of the line in Alcaeus F 384 e is typical of a pattern found in the songs of Alcaeus:

⏓ – ⏑ – – – ⏑ ⏑ – ⏑ – ⏓

This Alcaic meter is not to be found in songs attributed to Sappho. One modern expert has tried to explain this apparent anomaly by arguing that “she [= Sappho] chose it [= the Alcaic meter] because it was, in general, a favourite metre of her ‘correspondent’, and, in particular, the metre of the poem to which she is replying.”[41] {220|221}

3§30. Such an explanation is based on the assumption that Alcaeus and Sappho were simply two competing composers. This assumption leads to two alternative ways of interpreting the lyric exchange quoted by Aristotle:

- “… that the first part of the quotation […] comes from a poem by Alcaeus; the remainder […] from Sappho’s rejoinder.” [42]

- “… that the quotations in Aristotle come from a poem composed by Sappho in the form of a dialogue between herself and Alcaeus.” [43]

Either way we take it, “some have objected that, since Sappho appears to presuppose that her audience is aware of Alcaeus’ words […], it is hard to conceive of any but artificial arrangements for the presentation of the two poems to the public: were both presented, each by its own poet, to the same audience on different occasions?”[44]

3§31. The impression of “artificial” arrangements is shaped by the same assumption: that Alcaeus and Sappho were competing composers. In terms of my argument, however, we are dealing here not with competing songs composed by competing composers but with competing traditions in the actual performance of these songs. A survey of singing traditions around the world reveals a vast variety of comparable “boy-meets-girl” songs of courtship or pseudo-courtship. Some of these traditions feature musical dialogues between the lovers or would-be lovers, and there is a vast variety of scenarios, as it were, for success or failure in such ritualized games of love: a case in point is the Provençal lyric tradition of the pastorela, as I noted in earlier work.[45] Within the Greek lyric traditions themselves, another case in point is the “Cologne Epode” of Archilochus (P.Colon. 7511; F 196A ed. West, F S478 ed. Page).[46] It is most noteworthy that the setting of the first-person narrative of the Cologne Epode of Archilochus is a temenos ‘sacred space’, as we know from a poem of Dioscorides in the Greek Anthology (7.351). [47]

3§32. In Greek lyric traditions, the dialogic language of love can come to life even in situations where the first-person ‘I’ is talking to a second-person ‘you’ who does not talk back, as in Song 31 of Sappho.[48] {221|222}

3§33. I highlight a point of comparison in the popular music of several decades ago as of this writing: it is a song entitled “Oh, Pretty Woman,” composed by Roy Orbison with Bill Dees and performed by Roy Orbison, whose recording goes back to 1964 in Nashville, Tennessee. This is a song of a speaking ‘I’ talking his way through a tortured declaration of passionate love for a pretty woman who never talks back. The pretty woman walks on by without stopping to listen to the singer’s plaintive song of unrequited love. But then, most unexpectedly, she turns around and walks back to him. And it happens at the precise moment when he despairs of ever meeting her. Just as the song is reaching an end, the pretty woman who has been walking away from him is now all of a sudden walking back to him. What I find most remarkable about this song is that everything we hear happening in it happens while the speaking ‘I’ is singing to the pretty woman:

Pretty woman walkin down the street

Pretty woman, the kind I’d like to meet

Pretty woman, I don’t believe you

You’re not the truth

No one could look as good as you

Mercy

Pretty woman, won’t you pardon me

Pretty woman, I couldn’t help but see

Pretty woman, and you look lovely as can be

Are you lonely just like me?

… rrr …

Pretty woman, stop a while

Pretty woman, talk a while

Pretty woman, give your smile to me

Pretty woman, yeah, yeah, yeah

Pretty woman, look my way

Pretty woman, say you’ll stay with me

Cause I need you

I’ll treat you right

Come with me baby

Be mine tonight

Pretty woman, don’t walk on by

Pretty woman, don’t make me cry

Pretty woman, don’t walk away

OK

{222|223}

If that’s the way it must be, OK

I guess I’ll go on home, it’s late

There’ll be tomorrow night

But wait, what do I see?

Is she walking back to me?

Yeah, she’s walking back to me

O-oh

Pretty woman.

3§34. Since the voice of the pretty woman who is ‘walkin down the street’ is not heard in response, her character is in question. When the ‘I’ tells this woman that she is ‘the kind I’d like to meet’, does that wording make her the perfect woman or just a streetwalker who is ‘walkin down the street’—or both? In the beginning, the pretty woman is idealized. She looks too good to be true: ‘I don’t believe you | You’re not the truth | No one could look as good as you’. Words fail to express fully her loveliness: ‘you look lovely as can be’. But, despite all these worshipful words of admiration for the pretty woman, she is in danger of becoming a profanity by the time the song reaches the end: the streetwalker ‘walkin down the street’ who has been implored not to ‘walk on by’ but to ‘stop a while’ and to ‘talk a while’ will now be seen in the act of ‘walkin back to me’. And her character can be called into question precisely because she is about to come into contact with the questionable character of the ‘I’ who is singing to her. The ‘I’ had started reverently enough by addressing the pretty woman in the mode of a worshipful admirer. And, for a while, the wording continued to be reverent, but then the undertone of irreverence set in. The cry of ‘Mercy’ at the end of the first stanza already sounds less like an admiring exclamation and more like a predatory growl, which then devolves further into a non-verbal ‘…rrr…’ at the end of the second stanza. By now the sound resembles the mating call of a tomcat on the prowl.

3§35. In the musical meeting between Alcaeus and Sappho, by contrast, Sappho gets to talk back to Alcaeus. In their dialogue, she gets a chance to defend her character. It is not clear, though, just how successful such a musical defense can be. After all, the anonymous woman in the dialogue of the Cologne Epode of Archilochus likewise gets a chance to talk back to the speaker—and look what happens to her character: it will be ruined forever as the dialogue proceeds.

3§36. Here is the way it happens in the musical meeting of the Cologne Epode. As we start reading the fragment of the poem as we have it, we find {223|224} that the female speaker is already being directly quoted, as it were, by the male speaker. The fragment fails to show how the dialogue had started, and so our reading has to start in the middle of things, at a point where the dialogue is already in progress. But the sense is clear enough. The first five surviving verses show the female speaker already talking back to the male speaker. Her words are being quoted by the male speaker, who then marks in his first-person narrative the end of his quotation of her words: ‘such things she spoke’ (verse 6). Then he speaks back to her, quoting what he says (verses 7–27), but not before he signals in his first-person narrative the beginning of his self-quotation: ‘I answered back’ (again, verse 6). After he finishes what he says to the female speaker, the male speaker marks in his first-person narrative the end of his self-quotation: ‘such things I spoke’ (verse 28). And then he proceeds to narrate in the first person his success in winning the sexual favors of the woman he has just addressed (verses 28–35). That is how the narration in the Cologne Epode ostensibly ruins the woman’s reputation. In retrospect, however, in light of what is eventually narrated, her reputation has already been ruined from the very start. That is, she has ruined her own reputation by what she has already said at the very start, back when she is quoted as speaking in the first person (verses 1–5).

3§37. By contrast, in the musical meeting between Alcaeus and Sappho, we find no first-person narrative embedding the dialogue that is taking place between the first-person male speaker and the first-person female speaker. In this case, then, the mīmēsis is more direct. And the dialogue is therefore more theatrical, more musical. In the case of the Cologne Epode, by contrast, the dialogue is less theatrical—and less musical—because the mīmēsis is less direct. In that case the mīmēsis of the dialogue between man and woman is embedded within the overall mīmēsis of a first-person narrator who plays the role of the indecorous man reminiscing about his sexual conquest of the once-decorous pretty woman. {224|225}

3§38. The theatricality of a musical meeting between Alcaeus and Sappho is blurred, however, for those who assume that these two figures were simply “writers,” as we see from this sampling of rival explanations:

- (a) “A poem by two writers is hard to imagine in the sixth century.[49]

- (b) “Aristotle’s text […] implies either two poems by two writers or one poem (in dialogue-form) by one writer.”[50]

The theatricality stays blurred even if one “writer”—either Alcaeus or Sappho—is imagined as the composer of a functioning dialogue. Those who choose to imagine such a writer need to impose restrictions, as we see in the argument “that the poem is not a dialogue between Alcaeus and Sappho but between a man and a woman, or rather between a suitor and a rather unwelcoming maiden.”[51] In other words, a dialogue between would-be lovers seems imaginable only if neither Alcaeus nor Sappho is participating in the dialogue. It is assumed that Alcaeus and Sappho could not represent Sappho and Alcaeus respectively in such dialogic roles. After all, these figures are the equivalent of what we think is a writer. Surely a writer cannot be transformed into some kind of singing actor!

3§39. This is to misunderstand the medium of Alcaeus and Sappho, which as I have argued is fundamentally mimetic. The first person of Alcaeus and the first person of Sappho are ever engaged in roles of interaction with other persons. In terms of my overall argument, that is because the medium of Alcaeus and Sappho is not only mimetic. It is theatrical.

3§40. Which brings me to the question: did Sappho and Alcaeus ever meet? My answer is: yes, there was such a meeting—if you think of such a meeting as a staged musical event. Sappho and Alcaeus really did meet on the stage, as it were, of the festival held at Messon in Lesbos. And they could meet not just once but many times, as many times as a seasonally-recurring festival was being celebrated there.

3§41. The context for such a musical meeting at Messon, in terms of my overall argumentation, is sympotic. As such, this context is the source of a major problem in the transmission of songs attributed to Sappho. The problem has to do with a basic fact concerning sympotic events. The fact is, no woman could attend a symposium. Or, to put it differently, only women of questionable character could be imagined as attending. So a sympotic role for Sappho could not have been performed by Sappho even in the time of Sappho. Rather, such a role would be played out by men or by boys—or perhaps by women of questionable character.