2022.04.04 | By Gregory Nagy

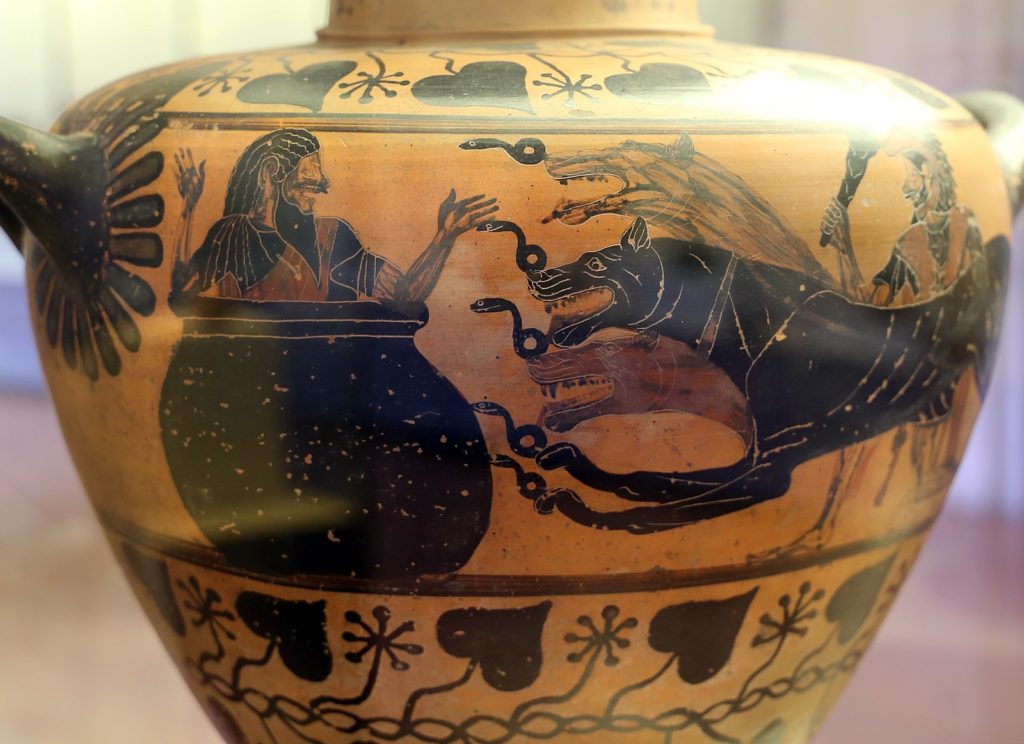

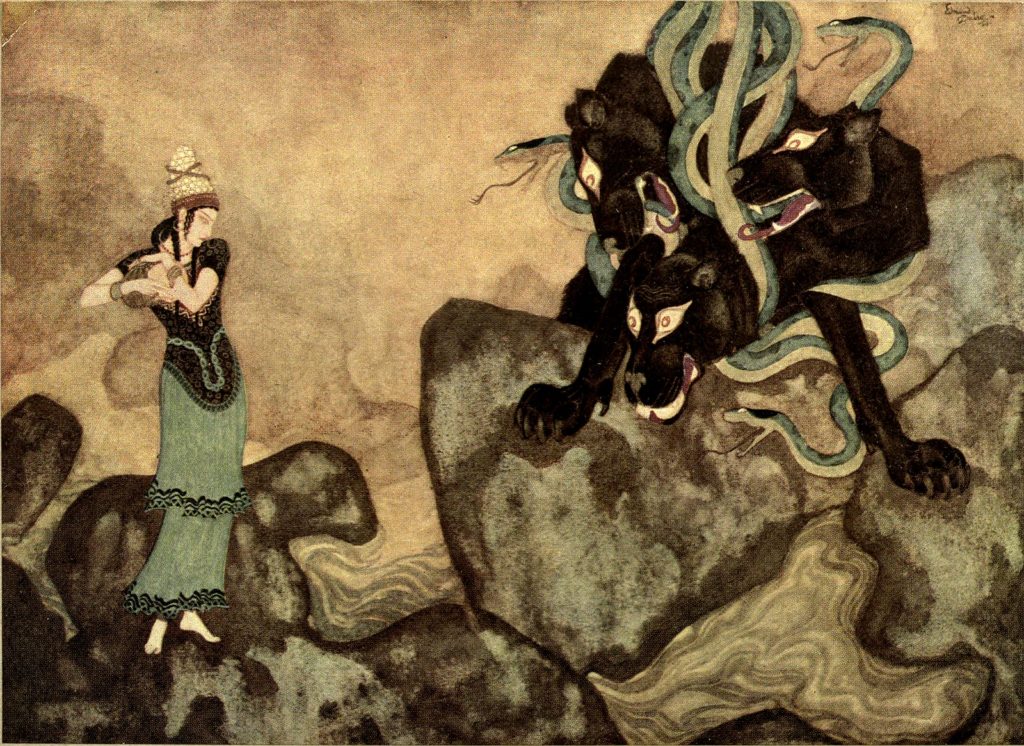

§0. In the passage I quote and translate here from Pausanias 3.25.5–6, our traveler is citing Homeric references to a monster described as ‘the hound of Hādēs’, commonly known as Cerberus, Pausanias must have in mind what we can read at Iliad 8.368 and at Odyssey 11.623; in the case of the Chimaera, a more multiform monster that exhibits snake-like as well as dog-like features, the relevant Homeric passage is Iliad 6.181. In the context of his describing the ‘hound of Hādēs’ as visualized at Tainaron in a region controlled by Sparta, Pausanias here at 3.25.5–6 decides to take an agnostic stance in analyzing the visualization. In other contexts, however, as we will see, our traveler reverts to pure reportage in narrating other versions of the myth as linked with other specific locales. As we will also see, Pausanias in those other contexts is not disputing the various different visualizations of the ‘hound of Hādēs’ as a dog. Accordingly, I argue that even here at 3.25.5–6 Pausanias does not really dispute the localized visualization of Cerberus as a dog. He is merely expressing here, in a not-so-unguarded moment, his learned affinities with Hecataeus of Miletus, FGH 1 F 27, who demythologizes Cerberus by trying to match localized mythological descriptions with his own scientific thinking about animals in real life, as it were.

{3.25.5} ἐποίησαν δὲ Ἑλλήνων τινὲς ὡς Ἡρακλῆς ἀναγάγοι ταύτῃ τοῦ Ἅιδου τὸν κύνα, οὔτε ὑπὸ γῆν ὁδοῦ διὰ τοῦ σπηλαίου φερούσης οὔτε ἕτοιμον ὂν πεισθῆναι θεῶν ὑπόγαιον εἶναί τινα οἴκησιν ἐς ἣν ἀθροίζεσθαι τὰς ψυχάς. ἀλλὰ Ἑκαταῖος μὲν ὁ Μιλήσιος λόγον εὗρεν εἰκότα, ὄφιν φήσας ἐπὶ Ταινάρῳ τραφῆναι δεινόν, κληθῆναι δὲ Ἅιδου κύνα, ὅτι ἔδει τὸν δηχθέντα τεθνάναι παραυτίκα ὑπὸ τοῦ ἰοῦ, καὶ τοῦτον ἔφη τὸν ὄφιν ὑπὸ Ἡρακλέους ἀχθῆναι παρ’ Εὐρυσθέα·

{3.25.6} Ὅμηρος δὲ—πρῶτος γὰρ ἐκάλεσεν Ἅιδου κύνα ὅντινα Ἡρακλῆς ἦγεν—οὔτε ὄνομα ἔθετο οὐδὲν οὔτε συνέπλασεν ἐς τὸ εἶδος ὥσπερ ἐπὶ τῇ Χιμαίρᾳ· οἱ δὲ ὕστερον Κέρβερον ὄνομα ἐποίησαν καὶ κυνὶ τἄλλα εἰκάζοντες κεφαλὰς τρεῖς φασιν ἔχειν αὐτὸν, οὐδέν τι μᾶλλον Ὁμήρου κύνα τὸν ἀνθρώπῳ σύντροφον εἰρηκότος ἢ εἰ δράκοντα ὄντα ἐκάλεσεν Ἅιδου κύνα.

{3.25.5} Some Greeks [Hellēnes] made[-in-their poetry] [poieîn] [a tale that told] how Hēraklēs had brought-up [-to-the-realm-of-light] [an-agein] the hound of Hādēs at-this-place [= Tainaron], though there is no pathway that leads underground through the cave—and though one cannot be readily persuaded to think that the gods originated any underground dwelling [oikēsis] where spirits [of the dead] [psūkhai] are to be assembled. But Hecataeus of Miletus invented a rationale that is a likely one: he said that a terrifying serpent [ophis] grew up at Tainaron and was called the hound of Hādēs, since anyone whom it bit was bound to die of its poison right then and there, and it was this serpent [ophis], he said, that Hēraklēs had brought [for display] to Eurystheus.

{3.25.6} But Homer, who was the first to refer to it as the hound of Hādēs—whatever it was that had been brought [for display] by Hēraklēs—did not give it any name, nor did he figure it into any [specific] form as he did in the case of the Chimaera. Those who came later [than Homer] made[-in-their-poetry] [poieîn] the name Cerberus [Kerberos], and, though in other respects they made him look like a hound, they say that he had three heads. Homer, nevertheless, does not imply that it was a hound domesticated by humanity, any more than if he had called a real serpent the hound of Hādēs.

§1. Despite his intellectual affinities with Hecataeus, Pausanias accepts whatever localized myths he reports. But he accepts these myths only as myths, in all their varieties, without incorporating into his own personal belief-system any truth-value claimed by the myths themselves. What we may consider to be true about these localized myths, it can be said in general, is not any single truth-value claimed by any single local myth, since each and every one of these myths will have its own different truth-values, and such truth-values will be mutually contradictory in their divergences just as they will be mutually reinforcing in their convergences. Rather, what is true about these local myths is that they are linked with local rituals. In terms of localized myth-ritual complexes, different locales could make the claim that it was at some special place in their very own locale where the hero Hēraklēs brought up into the light, out from the darkness of Hādēs, an infernal hound that he had subdued, and now Hēraklēs will deliver this prize to the cowardly king Eurystheus. This way, Hēraklēs can proudly display his own heroic bravura in overcoming—for the moment—the experience of death. He had entered Hādēs and had still somehow managed to return, after entrance, to the zone of light and life. For the moment, Hēraklēs seems to have overcome death by way of having subdued Cerberus, the guard-dog of Hādēs, and by even having brought the monster with him out of Hādēs.

§2. In the case of the locale named Tainaron, as in the case of other such locales, the landmark for the specific place where Hēraklēs came back up from down there in Hādēs, bringing Cerberus with him as his captive, is visualized in the context of a ritualized world that frames such a myth, and the landmark itself can be understood to signal in these cases both an entrance into and an exit out of the realm of darkness below.

§3. There is a striking parallel in Pausanias at 2.31.1, where our traveler retells another local version of the myth—this time, as he heard it told in the city of Troizen. During his visit there, he was shown a precinct sacred to the goddess Artemis which marked the place where Hēraklēs came up from the netherworld, bringing with him ‘the hound of Hādēs’. Pausanias also says here at 2.31.1 that this temple was founded, according to local myth, by the hero Theseus in gratitude to Artemis the Sōteira ‘Savior’ for her saving him from the Labyrinth; and it was at this same temple of Artemis, Pausanias continues, where the god Dionysus came out from Hādēs after having entered the netherworld in order to bring his mother Semele back to light and life after her experiencing of darkness and death. Pausanias goes on to remark that he cannot accept as a truth-value the idea that Semele ever died, and, as for the ‘hound of Hādēs’, he cross-refers to his statement of agnosticism further on at 3.25.5–6—the same statement that I have already analyzed.

§4. There is yet another striking parallel in Pausanias at 2.35.10, where we read a description of three sacred spaces in the city of Hermione. These spaces, Pausanias says, are situated behind the sanctuary of the goddess Demeter, whom the local population invokes as Khthoniā ‘she of the underworld’. These three spaces, Pausanias goes on to say (again, 2.35.10), are sacred to

A) the god called Klymenos: the name means ‘the one who is called by a name [unspecified]’, which is an epithet that Pausanias earlier at 2.35.9 describes as referring to ‘the king of the underworld’.

B) the god called Pluto (Ploutōn), who is treated here, at 2.35.10, as distinct from Klymenos

C) the ‘lake of Acheron’—where the name conjures the realm of the dead.

Pausanias goes on to say, again at 2.35.10, that there exists ‘in the place of Klymenos’ a chasm in the earth, and that it was through this chasm, in the mythological world of the people of Hermione, that Hēraklēs came up from the underworld, bringing up with him ‘the hound of Hādēs’.

§5. I give one more example from Pausanias, at 9.34.5: while our traveler makes his way through the region of Mount Laphystios in Boeotia, he notes a place where, according to local myth, Hēraklēs—again—came up from the underworld, bringing up with him ‘the hound of Hādēs’.

§6. Having briefly surveyed the descriptions by Pausanias of various mythological sightings, as it were, that centered on the moment when Hēraklēs emerges from Hādēs and brings with him Cerberus as a prize to show off his victory over death, I near a conclusion by focusing on one particular detail in one of these descriptions: at 2.31.1, as we saw, Pausanias says that a temple of Artemis the Sōteira ‘Savior’ at Troizen was founded, according local myth, by the hero Theseus in gratitude for being saved from death in the Labyrinth—and that this same temple was where Hēraklēs emerged from Hādēs, bringing with him the monster Cerberus as his prize. Such a connectivity of Theseus with Hēraklēs is highlighted in the Herakles of Euripides, where the bringing of Cerberus from Hādēs is described as the last of that hero’s Twelve Labors—a Labor that is almost ruined by a seemingly added Labor, where Hēraklēs unglues, as it were, a hapless Theseus who is glued by amnesia to the Throne of Lēthē, where a permanent erasure of memory prevents you from ever standing up again once you have sat down. In my comment on line 619 of the Herakles of Euripides, I say (Nagy 2022.03.28):

Hēraklēs refers to his rescuing of Theseus from the Throne of Lethe, where komizein ‘rescue’ implies ‘bring back to light and life’: for this implied meaning, see H24H 24§40. This act of rescuing Theseus is presented here as if it were an additional Labor of Hēraklēs in Hādēs, besides the act of capturing the hound Cerberus and bringing it to the realm of light. This additional Labor resulted in a delay, as it were, for Hēraklēs, which meant that he almost did not arrive in time to rescue his family from Lykos.

§7. I think we see here a distinctly Athenian fusion of myths, dramatized in the Herakles of Euripides, where (1) Hēraklēs brings Theseus back to the zone of light and life while at the same time (2) Hēraklēs takes Cerberus out and away from the zone of darkness and death. In terms of such a mythological fusion, the negative result is that Hēraklēs has thus brought the monster not only into the zone of life but also into the hero’s own life. What now results is toxic damage to the life of Hēraklēs. A wolfish rage, embodied by Cerberus, is transferred from this “hound of hell” to Hēraklēs himself, since this hero will now go mad and commit a most horrific deed: he will kill his own family. But there is also something positive that results from this horror. The pollution caused by the toxic madness of Hēraklēs will now have to be compensated by Theseus in return for that hero’s being liberated by Hēraklēs from the darkness of Hādēs—a darkness once guarded by Cerberus. Now Theseus, who as king of Athens is also the city’s chief priest, will have a chance to purify the pollution caused by the toxic horrors that happened in Thebes when Hēraklēs went mad there. Theseus will now establish, in Athens, a hero cult for the family of Hēraklēs—though not for Hēraklēs himself. Thus the Herakles of Euripides can be seen as a dramatization of an Athenian aetiology for such a hero cult, where the city of Athens appropriates, at least in part, the legacy of Hēraklēs in the dimension of myth by way of establishing, in the dimension of ritual, a hero cult for the family of Hēraklēs.

Bibliography

H24H = Nagy 2013 (The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours)

Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013.

Nagy, G. 2022.03.28. “A sampling of comments on the Herakles of Euripides: ready for annotation.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-the-herakles-of-euripides/.

3 responses to “Pausanias 3.25.5–6, on Herakles and Cerberus”

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

[…] Nagy, G. 2022.04.04. “Pausanias 3.25.5–6, with translation and comments.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/pausanias-3-25-5-6-with-translation-and-comments/. […]

[…] Nagy, G. 2022.04.04. “Pausanias 3.25.5–6, with translation and comments.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/pausanias-3-25-5-6-with-translation-and-comments/. […]

[…] Nagy, G. 2022.04.04. “Pausanias 3.25.5–6, with translation and comments.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/pausanias-3-25-5-6-with-translation-and-comments/. […]