MASt Seminar, Spring 2023 (Friday, May 19), Papers and Summary of the Discussions

Neighborly Relations: Continuity and disruption between Minoans and Mycenaeans and between Mycenaean and alphabetic Greek—two case studies

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Spring 2023 session of the MASt seminar by welcoming the participants to the May meeting and sharing great news as she presented the speakers of the meeting.

§2. The Spring 2023 MASt seminar marked Helena Tomas’s return to academic life and Bronze Age studies after a forced break due to a series of aneurysms she suffered in May 2019 requiring a long-induced coma. Before then, Helena was working on a paper, the completion of which was obviously put on hold until recently. With her characteristic energy and search for excellence, Helena enthusiastically committed to delivering an updated version of the paper at the Spring 2023 MASt seminar. However, due to the amount of scholarship on her topic that has appeared in the last four years, the speaker and the editors soon realized that a choice had to be made between fully updating the paper (and further postponing its publication) or publishing a slightly revised version of the paper now, which contains some updates in the comment session. We chose to publish with specific comments.

§3. On a more personal note, we celebrated a quite emotional Helena Tomas giving a talk in an international conference for the first time in over four years. While her physical recovery is still in progress, Helena’s excellent spirit, great humor, and brilliant mind are in great shape. No wonder she made history becoming the first director of an archaeological excavation directing from a wheelchair. All of us on the MASt team personally wish you a full and speed recovery, dear Helena!

§4. On a similar note, the organizers also expressed gratitude to Matthew for anticipating his talk, originally planned for a subsequent MASt seminar. The speaker originally planned for the Spring 2023 MASt seminar was compelled to withdraw with short notice due to health reasons—we are happy to report that our colleague is now fully recovered. The organizers adjusted the schedule accordingly and thank Matthew for his acceptance and the MASt network for the patience.

§5. The Spring 2023 MASt seminar “Neighborly Relations: Continuity and disruption between Minoans and Mycenaeans and between Mycenaean and the alphabetic Greek dialects—two case studies” focused on the analysis of Mycenaean tablets as a primary source for data at the crossroads between substratum cultures and languages and 1st millennium BCE outcomes.

§6. The speakers of the Spring 2023 MASt seminar examined different yet complementary aspects of the subjects, analyzed the scenario preceding Mycenaean as a language and Linear B as a script, and provided insights into what follows into the Bronze Age era.

§7. The first speaker was Helena Tomas, who gave the presentation “Similarities and differences between Linear A and Linear B clay tablets”. Tomas provided a multidisciplinary study of the clay tablets and focused on the pinacological aspects of the Linear A and Linear B documents. In particular, her paper examined how clay tablets were a crucial tool in both administrations but played quite different roles in each of the two systems.

§8. Matthew Scarborough was the second speaker and presented “Relative chronology and the outcomes of the Proto-Greek labiovelars in the context of ancient Greek dialect geography.” His talk focused on labiovelars, a quite unique linguistic feature in the context of the ancient Greek language since it is an Indo-European element that Mycenaean shows mostly as such, but underwent several changes and outcomes in the 1st millennium Greek dialects. Scarborough’s paper offers insights into the diachronic evolution of labiovelars and the geographical distribution of their alphabetic outcomes.

§9. Roughly 50 attendees took part in the Spring 2023 MASt seminar, among whom Matilda Agdler, Maria Anastasioadou, Eric H. Cline, Janice Crowley, Elena Dzukeska, Georgia Flouda, Anna Margherita Jasink, Hedvig Landenius Enegren, Joseph Maran, Michele Mitrovich, Leonard Muellner, Giulia Muti, Greg Nagy, Marie Louise Nosch, Thomas Olander, Birgit Olsen, Tom Palaima, Rachele Pierini, Vassiliki Pliatsika, Linda Rocchi, Matthew Scarborough, Kim Shelton, Helena Tomas, Brent Vine, Judith Weingarten, Roger Woodard, Assaf Yasur-Landau, Katarzyna Żebrowska.

§10. Substantial discussions followed each presentation. Specifically, contributions to the seminar were made by Maria Anastasioadou (see below at §42), Greg Nagy (§§50—51; 57; 80—95; 87; 98—99), Marie Louise Nosch (§§57—64), Tom Palaima (§§45—49; 53—54; 57—64; 86; 95—97), Rachele Pierini (§§57—64; 78; 91), Matthew Scarborough (§§75—77; 79; 90; 92; 94; 96), Helena Tomas (§§43; 44; 52; 56), Brent Vine (§89), Judith Weingarten (§55), and Roger Woodard (§§88; 93).

Similarities and differences between Linear A and Linear B clay tablets

Helena Tomas

University of Zagreb

§11. A comparison between Minoan and Mycenaean administrative systems has established that the former influenced the development of the latter, i.e. two Minoan administrative systems (Cretan Hieroglyphic and Linear A) influenced the development of the Mycenaean Linear B system (as elaborated in Tomas 2004; 2017b). This would appear obvious from a basic look at the similar types of administrative documents. However, more meticulous study shows that some similarities are only superficial and that in the scholarly literature the same names are sometimes applied to fairly distinct types of documents in the Minoan and Mycenaean systems. This problem has been stressed by Hallager (Hallager 1996; 2000; 2002) whose careful comparison of Minoan and Mycenaean sealings has revealed cases of similarities and dissimilarities between the Minoan and Mycenaean systems. I undertook my own analysis and reached similar conclusions as Hallager (see, for example, Tomas 2012b).

§12. This example of different sealings indicates that we must be more careful in equating the types of documents in the Minoan and Mycenaean administrative systems. This paper is dedicated to another case in which using the same term for groups of documents in Linear A and Linear B may mislead us to believe that they played the same role in the Minoan and Mycenaean administrative systems. The case in question is that of Linear A and Linear B page-shaped tablets. Elongated tablets are not discussed here simply because they were not used during the last phases of Linear A (they are discussed, however, in Tomas 2017a).

§13. The clay tablet is the most prominent document-type in Linear A and Linear B administrations (Palmer 2008:61–68; Palaima 2011:100–112). However, remarkable differences are noticeable on three levels: pinacology, epigraphy (the first two sets of differences are in detail discussed in Tomas 2011) and their roles in the administrative cycle.

§14. A comparison of pinacological[1] aspects of Linear A and B tablets shows differences in all the examined features. The shape of tablets, for example, differ significantly: whereas Linear B makes use of both page-shaped and so-called elongated tablet, only the former was employed during the latest stages of Linear A (see Tomas 2004:71 ff.; 2010; 2011).

§15. Size is also important. Linear A page-shaped tablets are generally smaller, as is the average amount of information on them. The proportions of the size of tablets and the crowdedness of signs show that Linear B page-shaped tablets hold a larger amount of information in the space available on the chosen writing surface.[2] There may be several reasons for this: one may be the different nature of the two languages, since the comparison of the number of signs in syllabic groups indicates that Linear A words may be generally shorter than those in Linear B (as argued by Duhoux 1978). Secondly, the methods of recording information may be different in the two scripts; one possibility, for example, is that Linear A used abbreviations more frequently—this was suggested to me by the late Anna Morpurgo Davies, who was the examiner of my dissertation at Oxford (Tomas 2004). Finally, the disparity in the length of texts may also imply certain differences in administrative practices; for example, Linear B page-shaped tablets may have been specifically intended to contain more information than Linear A tablets. There are three possible reasons for this last option: (1) in Linear A more extensive information was recorded on some other material, possibly perishable and Linear A flat-based nodules (with imprints of what may have been folded papyrus or parchment with a thin thread around it) which, according to Hallager, support the idea that a perishable material was used for writing;[3] (2) that Linear A tablets never reached an administrative level of recording for more extensive texts—in connection to this we may remember Olivier’s suggestion that Linear B tablets recorded palatial economy, whereas Linear A lower, so-called domainal economy;[4] or (3) that the larger and better organized Linear B page-shaped tablets were simply a result of the accumulation of administrative practices over time or of the expansion of the economy so that transactional relationships increased and required more sophisticated record-keeping.

§16. Epigraphical features which are even more relevant for the examined differences between Linear A and Linear B page-shaped tablets, such as opisthography, ruled lines, spacing or erasures become crucial in comparing and contrasting the extant inscriptions in both scripts, since these also reveal striking differences between Linear A and B tablets.

§17. Opisthography[5]

§17.1. A large number of Linear A tablets contain inscriptions on both of their sides. The function of Linear A opisthographic tablets is twofold. On some, the text from the recto is continued on the verso due to a lack of space on the recto (e.g. HT 93, HT 116). On some others, however, the recto and verso appear to be two separate lists and these changes are indicated by a different textual structure on the two sides, or by the introduction of new headings (e.g. HT 28, HT 85, HT 95), new logograms (e.g. HT 11) or new transaction signs on the verso (e.g. HT 44).[6] Linear A tablets are more commonly opisthographic than Linear B tablets. According to Schoep (2002:73), 26% of all Linear A tablets are opisthographic; more than half of these come from Haghia Triada. In Linear B administration opisthography is less frequently used: less than 4% of all Knossian tablets are opisthographic, and in Pylos this practice is even rarer, while it appears to have been unknown in Thebes and Tiryns. Only Mycenae shows a somewhat larger percentage—9% (Bennett 1958).[7]

§17.2. In Linear B administration, opisthographic tablets typically have continued lists on their recto and verso (e.g. KN Ce 152, KN Bk 799, KN C(2) 912), i.e. they do not have different lists on the recto and the verso, as is often the case with Linear A opisthographic tablets. From this we may tentatively argue that Linear B tablets, even when opisthographic, represent a single list, whereas Linear A tablets may contain more than one list. This reinforces an idea, elaborated below, that Linear A tablets were meant mostly for rough and temporary records. It did not matter that there were two different lists on a single tablet, as long as they were clearly separated (for example, by a ruled line), so that there could be no confusion when text was transferred onto a more permanent document. In Linear B, on the other hand, it was important that at the ‘page-shaped level’ of the administrative chain, each tablet was already a separate list, and not just a medium for ‘rough notes’ which were thereafter organized onto other documents (like papyrus, or parchment, as suggested by the use of flat-based nodules in the Linear A system (see above), and perhaps this feature indicates less reliance on perishable material amongst Linear B scribes.[8]

§18. Pleurography

§18.1. Pleurography is a rare epigraphic feature. It involves inscribing the sides of tablets, mostly due to a lack of space on an over-crowded tablet. A small number of Linear B tablets display this feature (ca. 50 tablets in Knossos, a few in Thebes and Pylos, one in Mycenae). No pleurographic inscriptions have been preserved on Haghia Triada tablets. As for other LM IB Linear A documents, there is one tablet from Palaikastro (PK 1), with a single sign inscribed on its latus dextrum. The reason for this appears to be the same: a lack of space.[9]

§19. Ruled lines.

§19.1. Nearly all Linear B tablets that have more than one inscribed line contain ruled lines between the lines of the text. In Linear A, ruled lines are not common. Not only are they rare, but their purpose is different from the purpose of ruled lines on Linear B tablets: with an exception of a tablet from Palaikastro (PK 1) and another one from Phaistos (PH 8a), they do not divide the lines of the text, instead they usually divide sections of contents, that is separate lists that form their own sections (e.g. HT 9b, HT 86a, HT 117a). This practice is irregular and not all sets of contents are divided by a ruled line. A change of contents is sometimes indicated by other means; for example, by spacing or a blank line.

§19.2. One tablet is unique: on HT 131b the ruled line does not separate two sections of contents, but the word that is taken to mean ‘grand total’ (PO-TO-KU-RO when we substitute known Linear B values for signs to their Linear A equivalent: Duhoux 2011:3, 6) from the rest of the text, probably to avoid confusion and make this word more noticeable in a somewhat messy text on this tablet.

§20. Line-spacing and blanks.

§20.1. Differences in line-spacing and blanks between Linear A and Linear B documents are mostly a result of a different lay-out of the text. In most cases Linear B scribes employ a columnar arrangement of the text (e.g. KN K(1) 875). In order to organize the text in this manner, blanks are often left between words, logograms and numbers. On Linear A tablets blank spaces are often a result of a disproportion between the size of the tablet and the length of the text (e.g. HT 17, HT 18). In some cases, however, spacing and blanks are used to emphasize certain words (like KU-RO, or PO-TO-KU-RO—e.g. HT 9b, HT 13, HT 94b, HT 122b) or to separate different sets of contents (e.g. HT 115b, HT 27b), but again this practice is not regular.

§21. Insertions and squeezing.

§21.1. On Linear A tablets there are three main reasons for insertions and squeezing: (1) scribal omission, (2) lack of space and (3) additional clarification. In Linear B these are relatively rare, which means that scribes relatively seldom made mistakes while inscribing, or misjudgments regarding the space necessary to fit the text on the tablet. Linear A scribes had a higher percentage of insertions and squeezing. This not only indicates that Linear A scribes made mistakes more often, but also that they were less skillful in organizing the space on a tablet in relation to the length of the text. If, however, clay tablets were only used for rough notes, perhaps no special attention was paid to fitting in the text properly (examples of a lack of space: HT 8b.4, HT 10a.4, HT 93a, HT 94a.2; (examples of squeezing due to scribal omissions: HT 10a.2, HT 12.6, HT 97a.1).

§22. Majuscules and minuscules.

§22.1 The practice of employing majuscules and minuscules has been noticed in Linear B, but not in Linear A. In Linear B majuscules were obviously used to put stress on a particular word (e.g. KN Lc (1) 525, KN Lc (1) 526).

§23. Palimpsests and erasures.

§23.1. On both Linear A and Linear B, palimpsests and erasures occurred for the same reason. Palimpsests were made once the information on the tablet became obsolete, and the tablet could be reused for a new record, whereas erasures were the result of scribal mistakes. As one may expect, more erasures occur on Liner A tablets (e.g. HT 29, HT 115).

§24. Layout of the text.

§24.1. Most of the epigraphical features addressed so far contribute to the layout of the text. Presented features show that Linear B tablets are better organized, more comprehensible, and clearer than those in Linear A (e.g. KN B 798, KN C (2) 911). Some Linear B tablets commence with a word in majuscule, interpreted as a sort of a heading, or as a more general information on the data to follow. This more general information was intended to catch the attention of the reader at the first glance. In the majority of cases Linear B tablets are very neat. When they contain more than one line, a ruled line is regularly incised between lines of the text to enhance clarity. Other means are also employed to improve the neatness of the inscription. For example, particular attention is paid to the arrangement of information: list-words, logograms and numerals are regularly arranged in columns. Spacing and squeezing (e.g. KN C (2) 911) have been used where necessary to preserve this columnar arrangement. Even when there is a lack of space, which is not often the case, signs are inserted in a way that maintains visual order (e.g. KN C (2) 911.6, .10). The text often fits comfortably on Linear B tablets,[10] without too much space left over or signs squeezed in due to a lack of space. This indicates a close collaboration between scribes and those who produced tablets (so-called flatteners), or perhaps even that scribes made their own tablets, as has been suggested by Palaima in the case of Pylos (Palaima 1985:102).

§24.2. In comparison to neat Linear B tablets, Linear A tablets look less organized and somewhat messy (e.g. HT 30, HT 31, HT 26a). On Linear A tablets no obvious means of emphasizing more significant information were applied, such as majuscules. Headings are therefore difficult to spot. Sometimes, when a new heading is introduced in the middle of the text, a blank space or a ruled line has been inserted preceding it to indicate the change, but not always. Apart from some examples of KI-RO (possibly meaning ‘deficit’), KU-RO (‘total’) and PO-TO-KU-RO (‘grand total’), no other parts of the text have a privileged position on the tablet that would be emphasized. Nor do Linear A tablets observe a columnar arrangement: no attention whatsoever is paid to placing list-words, logograms, and numerals under each other, which makes understanding the text more difficult. The lines were inscribed until there was no more space left, and then continued onto the next line.

§24.3. These remarks suggest that, unlike Linear B tablet-writers (Palaima 2011:34, 95, 121–127), their Linear A predecessors did not have strict rules about the organization of the text. Even apart from the lack of standardization, the text often looks messy. For example, the lines of the text are not straight on some tablet (e.g. HT 16), sometimes the ruled lines are not straight either (e.g. HT 106, HT 131b); on some tablets the sizes of the signs vary, etc.

§24.4. Three explanations for the textual disorganization of Linear A tablets are possible: (1) that Linear A scribes did not reach the level of writing clarity achieved by their Linear B counterparts—the chronological gap between the two groups may have given Linear B scribes enough time to improve the organization of their texts; (2) no general and strict rules about the organization of the text existed in Linear A and they varied from scribe to scribe. Finally, (3) Linear A tablets may have been less exposed to their future readers than those in Linear B.

§24.5. If that was really the case, Linear A scribes could allow themselves to write in the described way. Perhaps these tablets were more temporary than those in Linear B, possibly just drafts, and clearer and more comprehensible texts were to be copied soon afterwards; perhaps even by the same tablet-writers who would have had no trouble in understanding the text which they themselves had written.

§24.6. The same conclusion has been reached by Jan Driessen (1997:216), who names this phenomenon as writing in “familiar fashion”—it was either the same scribe who further processed the tablet, or his assistant who was familiar with his master’s handwriting. Ilse Schoep (1999:210) agrees and suggests that Linear A tablets “were intended to circulate within a restricted group, whereas Linear B tablets were destined for archival processing by third parties.” the only proper archive discovered so far has been a Linear B one – the Archive Rooms at Pylos (Chadwick 1958; 1968; Palaima and Wright 1985), no such archive with Linear A tablets has yet been discovered.

§25. To conclude this part of the paper. A detailed comparison of page-shaped tablets in the two groups of documents has revealed that there are more dissimilarities than similarities. Both their pinacological features and the relevant epigraphical features indicate profound differences. In some cases, these differences can be explained as an improvement of scribal practice from Linear A to Linear B, but in most cases, they clearly show that Linear A page-shaped tablets served a different administrative purpose from those in Linear B. The purpose of a detailed study of this issue, summarized in this paper, is to show that what we call a page-shaped tablet is in fact two distinct types of documents in Linear A and Linear B: I think that it is misleading to refer to them by the same name and, moreover, to assume that they played a similar role in the administrative cycle.

§26. Just above, I listed three possible reasons for the lack of organization of Linear A tablets in contrast to the later Linear B tablets. It is precisely the second of those options that I studied in more detail (Tomas 2012a). My next question therefore was: is it possible that all previously presented features are characteristic of only some tablet writers and not Linear A tablets in general. In other words: is it possible that different tablet writers simply had different rules for writing?

§27. In Linear B a study of scribal hands has been very successful and significant and has indeed improved our understanding of many aspects of Linear B administration.[11] When we move to Linear A such studies become more difficult and rarer, mostly because the study sample is much smaller. From some 400 Linear A tablets in total, only two sites have yielded a significant quantity of inscribed tablets: Haghia Triada has 147 tablets, and Chania 96 tablets. Unfortunately, most tablets from Chania are too fragmentary for any meaningful study of scribal hands and the epigraphical features tested against these, which means that the 147 tablets from Haghia Triada remain the best option, and this is why I focused my research on this assemblage (Tomas 2012a).

§27. The very first study of Linear A scribal hands was published by Raison and Pope (1971:XXn64). Later studies were undertaken by Louis Godart,[12] and his results were later included in the 5th volume of GORILA (1985:83-104). According to GORILA, out of the total of 147 Haghia Triada tablets, distinct scribal hands have been recognized on 63 of them, and the total number of these scribal hands is 18. Militello (1989), who carefully compared and modified Raison and Pope’s (1971 and 1977) and Godart’s (GORILA) classifications, differentiated 23 scribal hands (on 78 tablets). By adopting Militello’s classification, I tested particular scribal hands against pinacological and epigraphical features of the Haghia Triada tablets. My aim was to see if some of these features, like ruled lines to separate sets of contents, or spacing and blanks to separate and stress more important words, such as ‘total’ or ‘grand total’, are generally a Linear A scribal practice or they are specific only to some scribes. (I would like to remind you that those epigraphical features are not uniform in Linear A but occur sporadically, which prompted an idea that some features occur only on tablets of some scribes, but not of others.)

§28. Very detailed comparisons have shown that unfortunately this cannot be established as the case. The first problem was that the number of tablets allocated to each scribe was very small, sometimes only two tablets. The largest number of tablets allocated to one scribe is 10 – that is scribal hand 9. Thus some of the examined features do not occur frequently enough to establish firmer conclusions Furthermore, tablets allocated to some scribes are so fragmentary that the relevant pinacological or epigraphical features are simply not visible. Despite these difficulties, some results have been reached and I came to the conclusion that most Linear A scribes did not have their own writing rules, that is to say their individual writing style. They used the discussed features randomly, their style varied from tablet to tablet, sometimes even on the same tablet they applied different principles of organizing the text features on them.

§29. First of all, we cannot establish that some scribes specialized in writing only single-sided tablets, whereas others only opisthographic tablets. Many scribes have written both types, I said above that Linear A opisthographic tablets followed two different patterns: (1) the continuation of the text on the verso due to a lack of space on the recto, and (2) starting a completely new list on the verso. Most scribes employing opisthography do not appear to have preferences for either of these patterns. Ruled lines are a very rare epigraphical feature on Linear A tablets. As it has already been said, they do not divide each line of the text as on Linear B tablets, but different sets of contents or more significant words, such as ‘total’ or ‘grand total’. Spacing is sometimes also used for the same purpose. Both features are used sporadically: even on tablets by the same scribe they are sometimes used and sometimes not. Blanks are sometimes also used to divide sets of contents, or more significant words, but this feature is again used occasionally. Generally, Linear A scribes did not have strict rules about blanks before or after KU-RO: sometimes they put in blank space thus highlighting KU-RO, sometimes they did not care to make KU-RO more pronounced.

§30. Blank space is an interesting epigraphical feature and more frequent than ruled lines and line spacing. As we have just seen, blank space is sometimes left at the end of a line: either to separate and accentuate the following significant word, like KU-RO, or to separate a new heading and thus to signal the beginning of a new list. But blank space is also used to avoid splitting associated entries (by an entry I mean a cluster of information that goes together, for example a word and the associated quantity, or an ideogram and its quantity). Again, scribes used this feature randomly and Hand 11 is a good example of a scribe who had no strict rule about that. On tablet HT 7, line 3 he left a blank space to start a new entry in the following line, but then he split an entry in the very next line.

§31. The same is the case with Hand 9. Sometimes he shows these inconsistencies even on the same tablet. Thus, on HT 85a he makes sure not to split entries, on HT 85b he splits them although there is blank space on the bottom of the tablet and by using that space the split entries could have been avoided.

§32. Much more could be said about this topic. I focused mostly on epigraphical features, but testing pinacological features against each scribal hand has also been fruitful. It was, for example, interesting to notice that some scribes always used tablets of roughly the same shape and size (like Hand 1), but this could be just a pure chance of what has survived. Some other scribes did not show this feature: some of their tablets are bigger, some smaller; some of their tablets had sharp corners and straight edges, some had rounded corners and curved edges. The fact that a number of scribes wrote on tablets of a fairly distinct shape naturally led me to believe that they did not produce their own tablets, but that others were in charge of that task.

§33. To conclude. A careful comparison of specific Linear A epigraphical features and particular scribal hands did not result in showing that specific features are characteristic of only some Linear A Hands. Most epigraphical features appear to be known to all examined Linear A Hands but they used them occasionally and no specific pattern of when to use them and when not use them could be discerned. Not a single scribe proved to be consistent in applying the examined epigraphical features, and it was really interesting to see this sort of lack of consistency even on the same tablet. These Hands appear to be only occasionally preoccupied with writing their tablets in a clear fashion, some other times they could not be bothered with all those details. Sometimes they cared, sometimes they did not, and I have no idea which factors influenced their mood. We may suppose that on some days they were simply rushed, but the fact that epigraphical patterns sometimes vary on a single tablet goes against that excuse.

§34. In any case, Linear A scribes proved themselves to be very unpredictable. No examined scribe was consistent in his writing and most of them showed that they could be quite messy. In this paper I have mostly discussed the visual appearance of inscriptions. It has been observed that Linear B clay tablets are much more complex in how the text is laid out: they are better organized, handwriting is neat, the arrangement of the text is careful and orderly (e.g. Palaima 1988 and 2011).

§35. Most Linear A tablets, by contrast, are messy and disorganized. Whereas some scholars understand this as an advantage of Linear B, others take it as a sign of limited literacy: a Linear B scribe wrote in a neat manner to make sure that the other party would have no difficulties in reading the text, whereas a Linear A scribe even when messy (according to this scenario) would encounter no trouble in being understood, since people around may have been more acquainted with reading.[13]

§36. This contrast in neatness, however, provides ground for a different explanation. If we go back to the proposed explanations for the poor organization of Linear A tablets (see above), we can now introduce a fourth one: Linear B clay tablets may have been neat because they were summarizing records of previously recorded data. We know for sure that some Linear B large page-shaped tablets are records that compile and present the data from sealings and primary records of elongated tablets. Driessen (1999:207-208) named this practice a ‘three-tiered system’.

§37. In Linear A, on the other hand, we have no evidence of a similar process of transfer of information (apart from one case in Haghia Triada – tablet HT 24 and 45 noduli recording transactions of wool, see Hallager 2002; Del Freo 2008, 2012). I would therefore like to suggest that Linear A tablets were being composed on the basis of oral data (perhaps a dictation to a hand, and not written, hence their messiness. If Linear A scribes wrote tablets by following oral dictation, they may not have had time to organize their texts nicely. If the dictation was slow, they could have applied some of the described epigraphical features, but if it that dictation was fast, they not only had no time for advanced epigraphical features but were also messy as a result.

§38. Throughout my research on this topic, I was always ‘disappointed’ by these Linear A scribes, since it is sometimes so difficult to work out what they wrote. But perhaps they are not necessarily the ones to blame. Perhaps all those erasures, additional insertions, squeezing and similar non-pleasing aspects of Linear A texts, may not have been the fault of scribes, perhaps the dictating person was giving a confusing account.

§39. If all this makes sense, we may conclude that the visual organization of Linear A and Linear B tablets is not just a matter of aesthetics, but it reveals much more about the process of composing clay tablets in Minoan and Mycenaean societies, with the tradition (orality standing behind the former, and the tradition of scriptuality behind the latter. That would mean that there is yet another difference between Linear A and Linear B page-shaped tablets: their role in the administrative cycles of Minoan and Mycenaean societies.

§40. To summarize differences between Linear A and Linear B clay page-shaped tablets can be observed on three factors: pinacology, epigraphy and the role in the administrative cycle.

§41. The purpose of a detailed study of this issue, is to show that what we call a page-shaped tablet is in fact two distinct types of documents in Linear A and Linear B. It is misleading to assume that they played a similar role in the administrative cycle. All the presented differences indicate that that page-shaped tablets from the two administrative traditions have little more than their name in common.

Discussion following Tomas’s presentation

§42. Maria Anastasiadou asked whether it is possible to establish if the scribes were also the makers of Linear A tablets.

§43. Helena Tomas referred to the work of Erik Hallager, who worked on detecting and recording fingerprints on the tablets (Hallager 1996; 2000; 2002). Tomas specified that there is usually a number of different fingerprints on tablets, some of which seem to belong to the scribes as the clay should have been still moist to inscribe the tablet. This leads us to think, Tomas added, that in Linear A the makers and scribes were different people.

§44. Tomas then asked Tom Palaima if the same evidence has been retrieved for the Linear B tablets.

§45. Palaima observed that this method started to be used in the mid-1980s and what they initially discovered were two oddities. One, Palaima noted, was that fingerprints were not very visible at that time. Nowadays, different methods allow to detect a much larger number of fingerprints. Hopefully, Palaima continued, they will soon be able to clarify who handled the texts as it is still unclear because of the size of the palm prints.

§46. Tom Palaima moved on to discuss the second oddity; namely, the occurrence of peculiar left handedness that was explained by the possible presence of young apprentices using their young left hands to flatten the tablets against their right hands, so to apply the right force on them. This, Palaima remarked, justified also the predominance of small palm prints on the tablets. However, Palaima specified, it is not possible to know to what degree after the flattening process a scribe would pick up a flattened piece of clay.

§47. Tom Palaima observed that elongated tablets were made differently, and the clay was smoothed only after it had been rolled up. Palaima added that there may be traces of organic material, such as plant or woven material going through the center of the elongated tablets to give them protection against breakability.

§48. Palaima then remarked that he rejects the definition of scribe for this period as it may import ideas from Medieval times or the Near and Middle East that may not apply to the Minoan and Mycenean societies. Therefore, Palaima observed, the term tablet writers is preferable.

§49. Tom Palaima concluded that tablet writers would have played a role in the final shaping of the objects and their size to suit their needs, given especially the fact that long texts, like the landholding texts at Pylos, are preserved, where an elaborated formula on a columnar arrangement, such as the one of modern accounting book, is visible.

§50. Greg Nagy complimented Helena Tomas for her convincing work. Nagy added that he found particularly appealing the idea, accepted by Tomas, that the content of Linear A tablets may have been later transcribed into parchment or papyrus.

§51. Building on this point, Nagy asked Tomas about her interpretation of two Linear B words, namely za-we-te, which is like σῆτες in first millennium Greek and means ‘this year’, and pe-ru-si- which is like πέρυσι and means ‘last year’. Nagy explained that he interprets these terms as indicating the designations of this year versus the last year. This mind-set, Nagy observed, seems to indicate that the tablet writers of Linear B texts used perishable materials to transfer the information from the clay tablets into a more lasting format that is not yearly—as indicated by ‘this year’ and ‘last year’.

§52. Tomas remarked that the idea of perishable materials being used for Linear A texts had been suggested by Eric Hallager in the above-mentioned works. In reference to the words meaning ‘this year’ and ‘last year’ mentioned by Nagy, Tomas recommended Angeliki Karagianni’s PhD dissertation (Karagianni 2011), which deals with the topic of temporality.

§53. Tom Palaima further reflected on the possible use of perishable materials for keeping records by pointing out the different character of Linear B texts that are written on tablets and on parchment. Palaima suggested that the latter material, which does not preserve and neither did its impressions on, e.g., flat based nodules (out of use by that time), was reserved for the ornate and calligraphic type of script. Palaima then referred to the rare find of a tablet series on which such a complex sign had been written by a scribe in place of the usual simple header.

§54. Tom Palaima observed that Tomas mentioned Jean-Pierre Olivier’s idea that Linear A texts are domain whereas the Linear B texts are palatial. Palaima added that we have similar evidence, for example, from the House of the Oil Merchant at Mycenae. It is entirely possible, Palaima continued, that we are missing key aspects because of the archeological focus and what kinds of Linear B texts have been discovered.

§55. Judith Weingarten pointed out the existence of tablet PYR 2 which, although very fragmentary, has two ruled lines preserved on it.

§56. Tomas added that two more tablets with ruled lines are known, one from Palaikastro, the other from Phaistos.

§57. The last part of the discussion focused on bibliography. First, participants discussed a paper by Nagy (Nagy 1965) that compares Linear A and Linear B data. Next, we focused on the points for Tomas to review and expand in her ongoing research. The points Helena Tomas discussed with Marie Louise Nosch, Tom Palaima, and Rachele Pierini included:

§58. Olivier’s suggestion for identifying scribal hands in Linear B paleography was to have 30 reasonably diagnostic signs, and the potential application of such a minimum number to the comparisons Tomas is carrying on;

§59. How to explain the different length of Linear A and Linear B words, about which Palaima suggested that it might not have to do with the length of words spelled phonetically, but rather that in adapting a script that may have been created for an open-syllable language (like Japanese), to use with a language that has both closed syllables and consonant clusters, more signs were called into play (i.e. the same word might be spelled with different numbers of letters in the two scripts);

§60. The concept of “archive”, since some scholars are now pushing back against the very notion of “archives” based mainly on the lack of temporal span within the Linear B records—most modern-period archives are intended to last years, not months;

§61. Rethinking some Linear A and Linear B differences as well as some conclusions about the scribal hands at Hagia Triada in light of Salgarella’s work (Salgarella 2020);

§62. Reconsidering the impact of dictation of information during the record-making process in both Linear A and Linear B since records can be confused if one is distracted by having to examine or count or verify quantities, types and conditions of objects, recipients, etc. and devise formats for organizing this information extemporaneously;

§63. Accounting for further elements to be considered in the visual organization of Linear B tablets since there is a divide as to what the status of Linear B tablet-writers is and how they took in information (John Chadwick traced what he called aural/oral mistakes and Palaima thinks that in the Ta series a tablet writer was receiving item by item—sometimes grouped—oral descriptions of the inventoried items, some 74 or 75 in number).

§64. Reconsidering the impact of domainal vs. palatial sites in creating differences between Linear A and Linear B texts, which might be a much bigger factor than orality vs. literacy, in light of the fact that many Linear B texts are recording information that is truly vital to the functioning of the overall sociopolitical system (e.g. rations for specialist dependent workers and children connected with them; collections of recycled bronze for the production of military weaponry; ritual objects and instruments and foodstuffs for public ceremonies; offerings to sanctuaries and so on).

§65. Tomas’s Bibliography

Aravantinos, V. L., L. Godart, and A. Sacconi. 2002. Thèbes. Fouilles de la Cadmée III. Corpus des documents d’archives en linéaire B de Thèbes (1–433). Pisa and Rome.

Bennet, J. 2001. “Agency and Bureaucracy: Thoughts on the Nature and Extent of Administration in Bronze Age Pylos.” In Economy and Politics in the Mycenaean Palace States, Proceedings of a Conference held on 1-3 July 1999 in the Faculty of Classics, Cambridge, ed. S. Voutsaki and J. Killen, 25–37. Cambridge.

Bennett Jr., E. L. 1957. “Notes on Two Broken Tablets from Pylos.” Minos 5:113–116.

Bennett Jr., E. L., ed. 1958. The Mycenae Tablets II. Transactions of the American Philosophical Society 48(1). Philadelphia.

Chadwick, J. 1958. “The Mycenaean Filing System.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 5:1–5.

Chadwick, J. 1968. “The Organization of the Mycenaean Archives.” In Studia Mycenaea: Proceedings of the Mycenaean Symposium, Brno, April 1966, ed. A. Bartonĕk, 1–21. Brno.

Del Freo, M. 2008. “Rapport 2001–2005 sur les textes en écriture hiéroglyphique crétoise, en linéaire A et en linéaire B.” In Colloquium Romanum. Atti del XII Colloquio Internazionale di Micenologia (Roma, 20-25 febbraio 2006), ed. A. Sacconi, M. del Freo, L. Godart and M. Negri, 1:199–218. Pasiphae I. Pisa and Rome.

Del Freo, M. 2012. “Rapport 2006–2010 sur les textes en écriture hiéroglyphique crétoise, en linéaire A et en linéaire B.” In Études mycéniennes 2010. Actes du XIIIe colloque international sur les textes égéens, Sèvres, Paris, Nanterre, 20-23 septembre 2010, ed. P. Carlier, C. de Lamberterie, M. Egetmeyer, N. Guilleux, F. Rougemont, and J. Zurbach, 3–23. Biblioteca di Pasiphae X. Pisa and Rome.

Driessen, J. 1997. “Linear A Tablets and Political Geography.” In The Function of the ‘Minoan Villa’, Proceedings of the Eighth International Symposium at the Swedish Institute at Athens, 6-8 June 1992, ed. R. Hägg, 216–221. Skrifter utgivna av Svenska institutet i Athen 46. Stockholm.

Driessen, J. 1999. “The Northern Entrance Passage at Knossos. Some Preliminary Observations on its Role as ‘Central Archive’.” In Floreant Studia Mycenaea: Akten des X. Internationalen Mykenologischen Colloquiums in Salzburg vom 1.–5. Mai 1995, ed. S. Deger-Jalkotzy, S. Hiller, and O. Panagl, 1:205–226. Vienna.

Driessen, J. 2000. The Scribes of the Room of the Chariot Tablets at Knossos. Interdisciplinary Approach to the Study of a Linear B Deposit. Suplementos a Minos 15. Salamanca.

Duhoux, Y. 1978. “Une analyse linguistique du linéaire A.” In Études minoennes I. Le linéaire A, ed. Y. Duhoux, 65 –129. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 14. Leuven.

Duhoux, Y. 2011. “Linéaire A ku-ro, ‘total’ vel sim.: sémitique ou langue ‘exotique’?” Kadmos 50:1–13.

GORILA I–V = Godart, L. and J.-P. Olivier. 1976 (I), 1979 (II), 1976 (III), 1982 (IV), 1985 (V). Recueil des Inscriptions en Linéaire A. Études Crétoises 21. Paris.

Hallager, E. 1996. The Minoan Roundel and Other Sealed Documents in the Neopalatial Linear A Administration. Aegaeum 14. Liège and Austin.

Hallager, E. 2000. “New Evidence for Seal Use in the Pre- and Protopalatial Periods.” In Minoisch-Mykenische Glyptik. Stil, Ikonographie, Funktion: V. Internationales Siegel Symposium, Marburg 23.–25. September 1999, ed. W. Müller, 97–105. Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen Siegel Beiheft 6. Berlin.

Hallager, E. 2002. “One Linear A Tablet and 45 Noduli.” Creta Antica 3:105–109.

Ilievski, P. H. and L. Crepajac, ed. 1987. Tractata Mycenaea: Proceedings of the Eighth International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, held in Ohrid, 15–20 September 1985. Skopje.

Karagianni, A. 2011. Time in the Late Bronze Age Aegean: Examining Temporality in Knossos and Pylos on the Basis of the Linear B Documents and the Archaeological Record. PhD diss., University of Sheffield.

Militello, P. 1989. “Gli scribi di Haghia Triada. Alcune osservazioni.” La Parola del Passato 44:126–147.

Nagy, G. 1965. “Observations on the Sign-Grouping and Vocabulary of Linear A.” American Journal of Archaeology69(4):295–330.

Olivier, J.-P. 1967. Les scribes de Cnossos. Essai de classement des archives d’un palais mycénien. Incunabula Graeca 17. Rome.

Olivier, J.-P. 1968. “Pinacologie mycénienne.” In Atti e Memorie del Primo Congresso Internazionale di Micenologia, Roma 27 Settembre–3 Ottobre 1967, 2:507–512. Incunabula Graeca 25. Rome.

Olivier, J.-P. 1987. “Structure des archives palatiales en linéaire A et en linéaire B.” In Le systéme palatial en Orient, Gréce et a Rome. Actes du Colloque de Strasbourg, 19-22 juin 1985, ed. E. Lėvy, 227–235. Travaux du Centre de Recherches sur le Proche-Orient de la Grèce antique 9. Leiden.

Olivier, J.-P. 1990. “Les grands nombres dans les archives Crétoises du deuxieme millénaire.” In Pepragmena tou ST’ Diethnous Kritologikou Synedriou, A2:69–76. Chania.

Palaima, T. G. 1985. “Appendix.” In Pylos: Palmprints and Palmleaves, ed. K.-E. Sjöquist and P. Åström, 99–107. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology Pocket-book 31. Gothenburg.

Palaima, T. G. 1988. The Scribes of Pylos. Incunabula Graeca 87. Rome.

Palaima, T. G. 1990. “The Purposes and Techniques of Administration in Minoan and Mycenaean Society.” In Aegean Seals, Sealings and Administration: Proceedings of the NEH-Dickson Conference of the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory of the Department of Classics, University of Texas at Austin, January 11-13, 1989, ed. T. G. Palaima, 83–104. Aegaeum 5. Liège. Available at: https://sites.utexas.edu/scripts/files/2020/05/1990-TGP-AdministrationinMinoanandMycenaeanSociety.pdf

Palaima, T. G. 2000. “Transactional Vocabulary in Linear B Tablet and Sealing Administration.” In Administrative Documents in the Aegean and their Near Eastern Counterparts: Proceedings of the International Colloquium Naples, February 29–March 2, 1996, ed. M. Perna, 261–276. Turin.

Palaima, T. G. 2011. “Scribes, Scribal Hands and Palaeography.” In A Companion to Linear B: Mycenean Greek Texts and Their World, Volume 2, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies, 33–136. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 127. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Palaima, T. G. and J. C. Wright. 1985. “Ins and Outs of the Archives Rooms at Pylos: Form and Function in a Mycenaean Palace.” American Journal of Archaeology 89(2):251–262.

Palmer, R. 2008. “How to Begin?” In A Companion to Linear B: Mycenean Greek Texts and Their World, Volume 1, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies, 25–62. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 120. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Raison, J. and M. Pope. 1971. Index du linéaire A. Incunabula Graeca 41. Rome.

Raison, J. and M. Pope. 1977. Index transnuméré du linéaire A. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 11. Leuven.

Salgarella, E. 2020. Aegean Linear Script(s). Rethinking the Relationship between Linear A and Linear B. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge.

Schoep, I. 1994–1995. “Some Notes on Linear A Transaction Signs.” Minos 29–30:57–76.

Schoep, I. 1999. “Tablets and Territories? Reconstructing Late Minoan IB Political Geography through Undeciphered Documents.” American Journal of Archaeology 103:201–221.

Schoep, I. 2002. The Administration of Neopalatial Crete. A Critical Assessment of the Linear A Tablets and their Role in the Administrative Process. Suplementos a Minos 17. Salamanca.

Tomas, H. 2004. Understanding the Transition between Linear A and Linear B Script. PhD diss., University of Oxford.

Tomas, H. 2010. “The Story of the Aegean Tablet: Cretan Hieroglyphic – Linear A – Linear B.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 53(2):133–134.

Tomas, H. 2011. “Linear A tablet ≠ Linear B tablet.” In Pepragmena tou I’ Deithnous Kritologikou Synedriou / Proceedings of the 10th Cretological Conference, Hania, 1–8 October 2006, ed. M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki and E. Papadopoulou, A1:331–343. Chania.

Tomas, H. 2012a. “Linear A Scribes and Their Writing Styles.” In Inner Workings of Mycenaean Bureaucracy: Proceedings of the International Colloquium University of Kent, Canterbury, 19–21 September 2008, ed. E. Kyriakidis, 35–58. Pasiphae 5. Rome.

Tomas, H. 2012b. “The Transition from the Linear A to the Linear B Sealing System.” In Seals and Sealing Practices in the Near East. Developments in Administration and Magic from Prehistory to the Islamic Period. Proceedings of an International Workshop at the Netherlands-Flemish Institute in Cairo on December 2–3, 2009, ed. I. Regulski, K. Duistermaat, and P. Verkinderen, 33–49. Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 219. Leuven.

Tomas, H. 2013. “Saving on Clay: The Linear B Practice of Cutting Tablets.” In Writing as Material Practice: Substance, Surface and Medium, ed. K. E. Piquette and R. D. Whitehouse, 175–191. London. Available at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv3t5r28

Tomas, H. 2017a. “From Minoan to Mycenaean Elongated Tablets: Defining the Shape of Aegean Tablets.” In Aegean Scripts: Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, Copenhagen, 2–5 September 2015, ed. M.-L. Nosch and H. Landenius Enegren, 115–126. Incunabula Graeca 105. Rome.

Tomas, H. 2017b. “Linear B script and Linear B Administrative System: Different Patterns in Their Development.” In Understanding Relationship between Scripts: The Aegean Writing System, ed. P. M. Steele, 57–68. Oxford.

Relative Chronology and the Outcomes of the Proto-Greek Labiovelars in the Context of Ancient Greek Dialect Geography

Matthew J. C. Scarborough

University of Copenhagen

§66. Introduction: The problem of Classical Greek dialect geography

§66.1. A longstanding problem of Ancient Greek dialectology is the geographical distribution of the dialects as they are first attested in the Aegean in the Classical period (Figure 1). Since the ground-breaking studies of the dialect geography by Porzig (1954) and Risch (1955), most mainstream accounts of the dialects tend to admit the existence of four main subgroupings consisting of Attic-Ionic, Arcado-Cypriot, Northwest Greek / Doric, and Aeolic. In Porzig and Risch’s analyses these four groups may further fit more broadly into West Greek (Risch: North Greek) and East Greek (Risch: South Greek), although the exact alignment remains a perennial topic of debate.[14] A peculiar feature of Ancient Greek dialect geography is that it is characterized by two major dialect continua, namely those of Northwest Greek / Doric and Attic-Ionic, accompanied by four major dialect enclaves represented by Boeotian, Thessalian, Lesbian, and Arcadian.[15]

Figure 1: The Four Major Dialectal subgroupings of Ancient Greek in the Aegean[16]

§66.2. The main conundrum posed by the dialect geography here are the sharp discontinuities of these dialect enclaves. There is a need for a realistic historical hypothesis that can best explain the linguistic data in the geographic space that they are attested. The discontinuities are strongly suggestive of some kind of more recent disruption from a previous geographical distribution which would have preceded it in the late second millennium and early first millennium BCE, likely in connection with the general social and political disruptions in the Aegean following the collapse of the Bronze Age palatial economies. The lack of clear evidence for dialects other than Mycenaean and the apparent dialectal uniformity of Mycenaean Greek across sites, unfortunately, does not provide much to elucidate this picture.[17] To return to the picture of the first millennium BCE, some early literature attempted to use the Greeks’ own historiographic traditions about migrations at the end of the Bronze Age as an explanatory device for the attested dialect geography,[18] but the invocation of these traditions have since, quite rightly, been criticized, since much of the narratives from ancient authors claiming earlier migrations are closely bound up with the Classical Greeks’ constructions of ethnic identity that they were projecting onto mythic prehistory.[19] That said, it is nevertheless clear that the collapse of the Mycenaean palatial economies did entail great social upheavals in mainland Greece, and the dialect geography of the Classical Greek dialects may in itself provide some small clues towards broader historical processes.

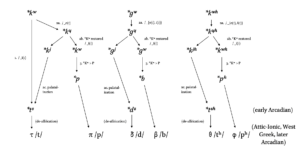

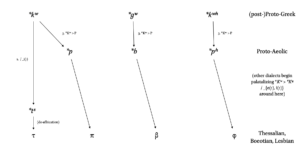

§66.3. For the remainder of this article, I would like to focus on the evolution of a single linguistic feature which may provide us an interesting case study to probe the limits of what the dialect geography of the early first millennium BCE may be able to tell us about the late second millennium, namely the evolution of the Proto-Greek labiovelar stops. The first reason for focusing on the labiovelars is that their loss is common to all Greek dialects of the first millennium BCE and demonstrably a late, post-Mycenaean development in most, if not all the first-millennium dialects. Secondly, the palatalization processes affecting the labiovelars appear to be spread throughout the dialects as an areal sound change irrespective of previous divergent evolution, and any discrepancies in the outcomes of the labiovelars may give indications of alternative relative chronologies in their development and have implications for the early history of the dialects. To this end, I will examine the evidence for labiovelar developments on the Greek mainland and propose that the developments in the dialects as attested in the first millennium BCE suggest two alternative relative chronologies of development: the first of these was a common Greek set of developments that affected most of the dialects, which the second chronology affected specifically the Aeolic dialects (Boeotian, Thessalian, and Lesbian). I will further argue that the first-millennium dialect geography is strongly suggestive that the Aeolic relative chronology applied earlier than those that affected the rest of the dialects. This has historical implications for the Aeolic dialect group as a whole and is of significance for interpreting some of the first-millennium discontinuities in Ancient Greek dialect geography.

§67. The labiovelars as an Ancient Greek dialectal isogloss

§67.1. To recapitulate the basic facts as can be found in the reference handbooks, Proto-Greek inherited a series of velar consonants from Proto-Indo-European with labial coarticulation (Proto-Greek *kʷ, *gʷ, *kʷʰ from PIE *kʷ, *gʷ, *gʷʰand secondarily labialized sequences of *k̑u̯, *g̑u̯, *g̑ʰu̯) conventionally called labiovelar stops.[20] It was realized early on in the comparative investigation of the Greek dialects that the labiovelars as reconstructed for Proto-Indo-European were retained in Proto-Greek on the basis of their differing sound correspondences among the attested Classical Greek dialects, for example:[21]

- PIE *kʷetu̯r̥- ‘four’ > Attic τέτταρες, Ionic τέσσερες, Doric τέτορες, but Thessalian and Boeotian πέτταρες(cf. Latin quattuor, Sanskrit catvā́raḥ, Old Lithuanian keturì, etc.)[22]

- PIE *gʷelbʰ– ‘womb, belly’ > Phocian and Attic-Ionic Δελφοί ‘Delphi’, etc., as a composition-member in Ionic ἀδελφεός < *sm̥-gʷelbʰ-ei̯o- ‘brother from the same mother’ (cf. Sanskrit sagarbhya- ‘brother of the same mother and father’), but cf. Boeotian Βελφοῖς ‘Delphi’ (dative plural at IG VII 2418.23, etc.), Thessalian Βελφαίο̄ ‘the Delphaian’ (genitive singular at IG IX,2 257.10),[23] Lesbian Βελφούς ‘Delphi’ (accusative plural, Etymologicum Magnum 200, 27)[24]

- PIE *g̑ʰu̯eh₁r- ‘wild animal’ > PGk. *kʷʰe̞ːr- > Attic θήρ, but Lesbian φῆρα (accusative singular at Alcaeus fr. 286b.3 Voigt); as a lexical Aeolism in Homeric φηρσίν ‘wild beasts; centaurs’ (dative plural at 1.268, etc.); cf. also the verbal derivative attested via Thessalian πεφειράκοντες (perfect participle active, nominative singular three times in IG IX,2 536, cf. Attic τεθηράκωτες)[25]

In addition to this, as Michael Weiss points out, there is also strong evidence from East Ionic to consider that the labiovelars were retained in East Ionic at the time of the colonization of Asia Minor, to judge from the basis of a sound law restricted to East Ionic which appears to have dissimilated labiovelar stops when occurring between two back vowels, e.g. Ionic ὅκως ‘how’ (cf. Attic πῶς), and additionally there is an outcome of a labiovelar which can be found the loanword πάλμυς (e.g. accusative singular πάλμυν in Hipponax fr. 3 West) < Early Ionic *kʷálmu- ultimately borrowed from Lydian qaλmλu ‘king’ (Weiss 2020:100, cf. also Hawkins 2013:188–190). In total, the internal evidence from the Classical dialects points to the retention of the labiovelars, being lost only relatively recently by the time of their earliest attestation.

§67.2. By the mid-twentieth century, the decipherment of Linear B as Mycenaean Greek through the cumulative efforts of Emmett Bennett Jr., Alice Kober, Michael Ventris, and John Chadwick led to the discovery that the labiovelars remained intact in the Mycenaean dialect and were represented using the q-series syllabograms, for example:

- PIE *gʷou̯-kʷól(h₁)o- ‘cowherd’ : Mycenaean qo-u-ko-ro /gʷou̯-kólos/ (TI Ef 2, etc.), Attic βουκόλος (cf. the nearly perfect cognate match to be found in Middle Irish búachaill, Middle Welsh bugail < Proto-Celtic *bou̯-koli-);[26] but

- PIE *h₂m̥bʰí-kʷol(h₁)o- ‘attendant’ : Myc. a-pi-qo-ro /ampʰí-kʷolos/ (TH Of 34.1, etc.), Attic ἀμφίπολος (Lat. anculus ‘servant’, cf. Skt. °cārá- in pari-cārá- ‘servant’, etc.)[27]

We may also note that while the labiovelars are intact here in early Greek, already one sound change has already occurred affecting them, since the labiovelar present in the compositional member *-kʷól(h₁)o- has regularly become a plain velar in the environment of a preceding *u or *u̯.[28] The discovery that the labiovelars were preserved almost completely intact in Mycenaean still in the late second millennium BCE (with the exception of this early dissimilation) may also corroborate the earlier adduced evidence that the loss of the labiovelar stops was relatively recent in the Classical Greek dialects; however, I would urge exercising some caution since we cannot assume that the state of affairs as attested in Mycenaean is the same in other second-millennium dialects that are unattested but we can assume to have existed on the basis of the first-millennium dialect geography.

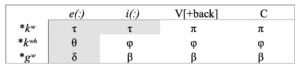

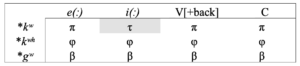

§67.3. The main distribution of the outcomes of the labiovelar stops in Attic-Ionic and in West Greek which overwhelmingly appear to be the ‘normal’ outcomes are summarized in Table 1 below:[29]

Table 1: The Reflexes of the Proto-Greek Labiovelars in Attic-Ionic and West Greek Dialects

Before *e(ː) the labiovelars become dentals with phonetic features corresponding to their original voicing and aspiration:[30]

- *-kʷe ‘and’ > τε ‘and’ (Latin -que, Sanskrit ca, etc.)[31]

- *sm̥-gʷelbʰ– in ἀ-δελφ-ός ‘brother’ (cf. Sanskrit sagarbhya- ‘brother of the same mother and father’)[32]

- *gʷʰer-mo- > θερμός ‘warm’ (Armenian ǰarm ‘warm’, cf. Sanskrit gharmá- ‘heat’, Latin formus ‘warm’, Proto-Germanic *warma- < *gʷʰor-mó-)[33]

Before *i(ː) the distribution is split: The voiceless labiovelar *kʷ also has a dental reflex /t/ as before *e(ː), for example in the case of the relative-interrogative pronoun:

- *kʷis, *kʷid > τίς, τί ‘who, what’ (Hittite kuiš, kuit, Latin quis, quid, etc.)[34]

Exceptionally, however, voiceless aspirated *kʷʰ and voiced unaspirated *gʷ have labial outcomes:

Typically, the dental reflexes that are found before *e(ː) and *i(ː) are explained as the result of a typologically common process of palatalization occurring before front vowels. In a typical palatalization process the place of articulation of a preceding consonant is moved forward in the mouth as a result of it being affected by the articulatory properties of a following mid- or high-front vowel.[37] The distribution before high-front *i(ː) in the majority of the Classical Greek dialects is split with the reflex of the voiceless labiovelar exhibiting a voiceless dental /t/, while the voiced and voiceless-aspirated labiovelars failed to undergo the same palatalization process. The split distribution of the labiovelars before *i(ː) is a separate problem which will be further addressed at §70 and §71 below. For now I will turn to the outcomes in Arcadian in §68 and in Aeolic in §69, since I will further argue below that the process of this unusual distribution in Attic-Ionic and West Greek can be better understood through comparison with the outcomes in these dialects and the nature of how the palatalization of the labiovelars was spread.

§68. The special case of Arcadian <Ͷ> (and other unusual spellings)

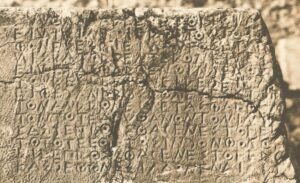

§68.1. It is well known that archaic Arcadian inscriptions occasionally attest a special character tsan, which I have transcribed here as <Ͷ>, and other unusual spellings whose precise phonological values remain unclear, but appear to represent an intermediary state of development of sounds that reflect labiovelars etymologically.[38] These are most famously attested in a fifth-century inscription from Mantinea recording judgements of persons guilty of sacrileges to the temple of Athena Alea (IG V,2 262, see Figure 2), but now with certainty four additional times in a new festival calendar from Arcadia (Heinrichs 2015, Carbon and Clackson 2016).[39]

Figure 2: Detail of IG V,2 262, col. ii, l. 24–36 (after Comparetti 1914, Plate 1)

To make my general point I will restrict myself to discussing the evidence of <Ͷ> for the palatalization of the labiovelars in archaic Arcadian inscriptions but see especially Dubois (1986a:64–70) and Duhoux (2006) for more extensive discussions of these forms and other unexpected spellings of Arcadian forms using <ζ> epigraphically and in glosses.[40]

- Examples of *kʷi- > Ͷι-

- Ͷι[ν]’ (τινά) (IG V,2 262.23)

- Ͷις (τις) (IG V,2 262.25, 27)

- Examples of *kʷe- > Ͷε-

- εἴͶ’ (εἴτε) (IG V,2 262.26)

- εἴͶε (εἴτε) (IG V,2 262.26, 27, 28, 29, 31)

- ὁͶέο̄ι (ὁτέωι) (IG V,2 262.14)

- Examples of *gʷe- > Ͷε-

- ὀͶελο̄́ ‘two obols’ (nom.-acc.du.) (Carbon and Clackson 2016:122, l.13) < Proto-Greek *ogʷeló- (cf. Attic ὀβολός < *ogʷoló-)

- ὀͶελόν ‘obol’ or ‘spit’ (contextual sense unclear) (acc.sg.) (Carbonand Clackson 2016:122, l.19)

- Other examples of <Ͷ>

- ἀπυͶεδομίν[ος](ἀποδεδομένους) (IG V,2 262.19)[41]

- ͶεσͶάρο̄ν̣ ‘four’ (gen.pl.) < *kʷetu̯r̥- (Carbon and Clackson 2016:122, l.11)

On the basis of these examples, we may observe that <Ͷ> is writing a sound that is intermediate and show an ongoing process towards the dental outcomes that are found in other Arcadian dialect inscriptions. It is notable that tsan is very likely being used primarily to distinguish what is probably a feature of affrication which is not phonemically identical in all cases, since the attested examples are used regardless of etymologically expected voicing contrasts (cf. εἴͶε (εἴτε) ‘and if’ versus ὀͶελόν ‘obol; spit’ above) or even specifically the affricates specific to the outcome of palatalized labiovelars (cf. <σͶ> in the spelling of ͶεσͶάρο̄ν̣ ‘four’ reflecting the intermediate outcome of *-tu̯-, possibly via *-stˢ-).[42]

§68.2. Later Arcadian from the fourth century onwards attests dental forms in these environments congruent with the outcomes found in Attic-Ionic and West Greek, for example:[43]

- Examples of *kʷi- > τι-

- τι ‘what’ (IG V,2 3.5), etc.

- τιμασίαν (Dubois 1986b:61–63, Té 4 l.17), abstract derivative of Arcadian *τιμά < *kʷi-meh₂[44]

- Examples of *kʷe- > τε-

- Full-grade derivatives of PIE 3.*kʷei̯- ‘to pay’ in ἀπυτεισάτω (3.sg.aor.imptv., IG V,2 6.32), etc.

- πέντε ‘five’ (IGV,2 3.1) < *pénkʷe

- In εἴτε ‘and if’ (IGV,2 343.10), etc. < *-kʷe

- τετόρταυ ‘fourth’ (gen.sg.f. IG V,2 6.104), cf. Attic τετάρτης from stem *kʷetu̯r̥-to-

- Examples of *gʷe- > δε-

- ὀδελός ‘obol’ (IGV,2 3.19, 24), cf. (14) above.

- ἐσδέλλοντες ‘throwing’ < as though continuing *eks-gʷelh₁-i̯e/o- (IG V,2 6.49), cf. Attic ἐκ-βάλλοντες[45]

§68.3. Individual problems in interpreting the granular phonetic data aside, we may nevertheless assume that the spellings using tsan represent an intermediary step to what also happened in Attic-Ionic and West Greek, given that the reflexes in later Arcadian are congruent with all other Greek dialects with the exception of Boeotian, Thessalian, and Lesbian.[46] The further implicature of this, taking the attested dialect geography into consideration, is that the sound changes associated with the palatalization of the labiovelars passed through the dialect geography as an areal sound change, regardless of existing isogloss boundaries or other linguistically divergent evolution. The fact that Attic-Ionic and West Greek agree on these outcomes was already suggestive of this, but taking the Arcadian evidence where the sound change only came to completion in the mountainous interior of the Peloponnese by the fifth century BCE is further strong evidence of the nature of the propagation of these developments.

§69. The outcomes of the labiovelars in Boeotian, Thessalian, and Lesbian

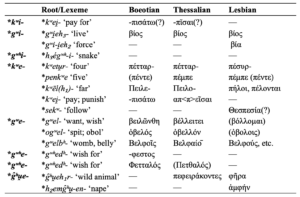

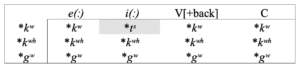

§69.1. As for the outcomes in the Aeolic dialects, there is a mixture of dental and labial reflexes between front vowels that need to be sifted and sorted. Elsewhere I have collected and analyzed the attested examples (Scarborough 2023:68–88, with full references from documentary sources). The main synopsis of the attested forms may be found in Table 2 and Table 3.[47]

Table 2: Synopsis of Labial Reflexes of Labiovelars

Regarding the labial reflexes of the labiovelars in the Aeolic dialects, I note that there are only two potential examples attesting a labial reflex for the labiovelars before high-front *i(ː), namely in Boeotian ἀποπισάτω ‘let him pay’ (SEG22:407.33, 3rd c. BCE, = Attic ἀποτεισάτω) and ποταποπιάτω ‘let him pay besides’ (IG VII 3172.85, ca. 222–200 BCE, = Attic προσαποτεισάτω). However, these two examples are not secure because they postdate the Boeotian narrowing of high-mid /eː/ to high /iː/,[48] and on the basis of comparison with other dialects the continuation of a full-grade form *ἀποπεισάτω is expected here.[49] Thessalian only attests a single counterexample ἀπ<π>ισαι (IG IX,2 1202.5, undated, archaic script), but in several other places the expected full-grade aorist forms are attested: infinitives ἀππε[ῖσ|α]ι (IG IX,2 1226.10–11, 5th c. BCE) and ἀπ<π>εῖσαι (Giannopoulos 1934–1935, No.1.11, 6th c. BCE?), and the third singular aorist imperative ἀππεισάτου (IG IX,2 1229.28, early 2nd c. BCE), so it is more likely that ἀπ<π>ισαι of IG IX,2 1202 is a one-off misspelling. Consequently, there are no clear examples for labial reflexes of original *kʷi- > πι- in Thessalian or Boeotian. In the remaining environments before high-front *i(ː) dental reflexes are found.

Table 3: Synopsis of Dental Reflexes of Labiovelars

While the outcomes of labiovelars in the Aeolic dialects before front vowels are largely in favor of labial outcomes (except *kʷi- and *gʷʰi- where there are no clear examples for labials), a small handful of dental reflexes remain. The most prominent examples before high-front *i(ː) are the relative-interrogative τίς, τί < *kʷis, *kʷid, and Lesbian τίμα, Boeotian and Thessalian τιμά ‘compensation, payment’ < *kʷi-meh₂ (Attic τιμή), never attested as †πίς, †πί or †πίμα/πιμά. Additionally difficult is the regular form of the enclitic conjunction τε < *kʷe, never surfacing as †πε. The occasional reflexes of PIE *penkʷe ‘five’ and derivatives of PIE *gʷelbʰ– ‘womb, belly’ have counterexamples with the more marked labial outcomes elsewhere. There is also a single early example for *gʷʰe attested in θ̣έρμαν (Alc. 143.10 Voigt), albeit in a fragmentary context.[50]

§69.2. To assess the comparative value of labial vs. non-labial reflexes of labiovelars in the Aeolic dialects, it is clear that the labialized examples before *e(ː) strongly outweighs the evidence for dental reflexes in the same environment. The enclitic conjunction τε < *kʷe is the most puzzling counterexample, and the most economical hypothesis to account for it would be to assume an early loss in these dialects, and then a re-borrowing from the literary or Homeric oral-poetic register. Short of setting up a restricted sound law that applies only to this environment for clitics (cf., e.g. Stephens and Woodard 1986:147, Lejeune 1972:45), the hypothesis of supradialectal borrowing seems to me to be the most plausible solution, given that it seems methodologically difficult to justify an entire sound law for which this is the only example, in addition to the observation that cross-linguistically connectors are the grammatical structures most susceptible to borrowing.[51] The Aeolic treatment of *kʷi- > τι- in Boeotian and Thessalian τιμά, Lesbian τίμα and especially in the relative-interrogative pronoun τίς, τί, which is far less likely to be a borrowing,[52]strongly points to the regularity of this sound correspondence in this environment.[53]

§70. Remarks on the observed distribution of the labiovelars

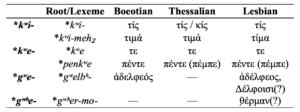

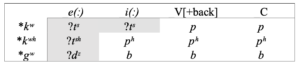

§70.1 To simply consider the attested sound correspondences, in addition to the ‘normal’ outcomes summarized in Table 1 above, we may add the synopsis of the observed ‘Aeolic’ outcomes in Table 4 below:

Table 4: Observed Reflexes of the Labiovelars in Boeotian, Thessalian, and Lesbian

As discussed at §69.1 and §69.2 above, the main distribution of the labiovelars in the Aeolic dialects tends towards complete labialization, but a small number of difficult exceptions remain. Most of these can be attributed to a concession to broader supradialectal tendencies and isolated dialectal loanwords, but the cases of the relative-interrogative *kʷis > τίς and *kʷi-meh₂ > Boeotian, Thessalian τιμά, Lesbian τίμα are much more difficult to dismissfor *kʷ developing to the voiceless dental /t/ before high-front /i/. Meanwhile, the ‘normal’ outcomes as found in Attic-Ionic, West Greek, and later Arcadian exhibit the outcomes described at §75.3. above, where the labiovelars are regularly palatalized to dentals before *e(ː), and the voiceless labiovelar *kʷ is palatalized to a dental before *i(ː). The first observation I make from this distribution is that there seems to be something special about the restricted environment of the voiceless labiovelar *kʷ before high-front /i/, where this appears to be not only the regular outcome in most of the dialects, but also in Aeolic where labialization appears to be regular in all other environments.

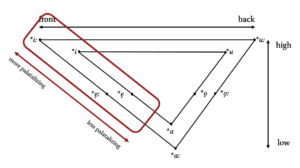

§70.2. The second observation that I would make following upon the previous one, is that the split distribution before *i where *kʷ palatalizes while *gʷ and *kʷʰ do not, despite regularly palatalizing before *e, is typologically unusual if one is expecting a simple palatalization process. To put it another way, the relative ability of a vowel to palatalize a consonant is on a gradient on the front-high axis of the vowel space, since this is the area of the vowel space where the tongue moves closer to the hard and soft palate of the mouth. Because of this the high front vowel /i/ gives the narrowest constriction to the palate, and so is the vowel that is most likely to palatalize a preceding consonant, and this effect becomes less likely the further back and low the articulation of the vowel is (see Figure 3).[54]

Figure 3: A Reconstruction of the Proto-Greek Vowel Space with a Typology of Typically Palatalizing Environments Overlaid

With this held in mind the crux of the matter is: if /i/ is the vowel that is prototypically more susceptible to palatalizing consonants, why do *gʷi-, *kʷʰi- escape palatalization while the labiovelars become palatalized before /e/ in the non-Aeolic dialects? Both observations from §70.1 and §70.2 appear to point to a much more complicated story in Aeolic and the other Greek dialects in the Aegean.[55]

§71. A proposed solution for Attic-Ionic, West Greek, and Arcadian

§71.1 The most economical solution to deal with the problem of the split reflex of the labiovelars before /i/, to my knowledge, was a proposal made by H. N. Parker (2013) which is the solution I adopt here and will outline in brief. Parker, however, has earlier argued against the historical unity of the Aeolic dialectal subgrouping and so the broader historical implications of his analysis in view of the dialect geography and the non-arboreal propagation of the palatalization of the labiovelars before /e/ in most of the dialects may be productively further expanded upon.[56]

§71.2 The first part of these developments addresses the first observation made in §70.1, namely that in all dialects, even Aeolic, the voiceless unaspirated labiovelar stop *kʷ has palatalized to a dental. The first stage of these developments therefore ought to be an early palatalization of only the voiceless unaspirated labiovelar *kʷ specifically restricted to the typologically most palatalizing environment preceding long or short *i (19).

- *kʷ > *tˢ > t / _i(ː)

A similar early palatalization of this specific environment was also proposed by Stephens and Woodard (1986:133) where the sequences of *kʷʰi and *gʷi may have been less susceptible to palatalization because of their additional phonetic properties (cf. Stephens and Woodard 1986:143–145 with typological parallels). In effect, this restricted sound change uniquely removes the voiceless unaspirated labiovelar *kʷ and sends it down an alternative sequence of developments from the other two labiovelars in this environment from the very beginning.

Table 5: The ‘normal’ reflexes after the Stage 1 developments

§71.3. The crucial intermediary step is the beginning of a palatalization process of the remaining labiovelars before i(ː) and e(ː). In these environments the labial element of the labiovelar stops would become labiopalatal in articulation:

- *Kʷ > *Kᶣ / _{e, i}(ː)

But crucially, following the argument of Parker (2013: 223), before long or short /i/ the labiopalatal element [ɥ] did not fully delabialize in the sequence [ᶣi] because it would have created a cross-linguistically disfavored sequence [ʲi].[57]In this environment new learners could have reanalyzed these retained sequences of [ᶣi] as allophones of the labiovelars that were still independent phonemes in the phonological system, and so in the specific environment before *i(ː) the labiovelars were restored.[58]

The remainder of the labiopalatals which continued to exist before *e(ː) would lose the labial feature and proceed down a familiar path of palatalization, eventually merging with the affricates and developing with them.

§71.4. Once the labiopalatals were restored to labiovelars before /i/ the remainder of the labiovelars would have lost their velar co-articulation in all environments giving the remainder of the labial outcomes. Cross-linguistically, at least among the early Indo-European languages this is a common sound change with parallel developments in the Sabellic languages and in some varieties of Celtic.[59] This is likely to have occurred in most dialects prior to the resolution of the palatalizations which took place as described at §71.3, since this wave of labialization is already present in the early Arcadian inscriptions which attest tsan as a grapheme, e.g. φονε̄́ς ‘murderer’ < *gʷʰon-es- (IG V,2 262.26, 30; cf. Attic φονεύς), βο̴ν ‘ox’ < acc.sg. *gʷōm (Carbon and Clackson 2016:122, l.7), etc. (see Table 6).

Table 6: The approximate state of affairs as attested in early Arcadian

Following the state which we have attested in early Arcadian, the only remaining change necessary to arrive at the pan-Greek ‘normal’ outcomes of the labiovelars is the resolution of the phonemes represented in early Arcadian through tsan (via de-affrication?) as dental stops, completing the palatalization process and is congruent with the observed outcomes as outlined in Table 1 at §75.3. above.

§71.5. An approximate relative chronology of the entirety of the developments concerning the palatalization and labialization of the labiovelars in Attic-Ionic, West Greek, and Arcadian is schematized in Figure 4.

Figure 4: A Schematized Relative Chronology for the Labiovelars in Attic-Ionic, West Greek, and Arcadian

§72. The relative chronology of the labiovelars in Aeolic versus other dialects

§72.1. At §69.2 and §70.1 I argued that the observed outcomes of the labiovelars in Boeotian, Thessalian, and Lesbian appears to regularly reflect *kʷi > τι, with full labialization in all other environments. The simplest solution to account for this distribution would be an assumption of a different rule ordering first assuming a pan-Greek palatalization of the voiceless unaspirated labiovelar *kʷ in the restricted environment when followed by high-front *i (§71.2), followed by a subsequent labialization of all the labiovelars in all remaining environments (§71.4), bypassing the process of the second palatalization before front vowels entirely (§71.3).