1§5. While I agree that the over-scaled winged warrior represents the afterlife hero Achilles, my account will reject the notion that the composition illustrates a scene based on a text or myth directly. The entire song culture backgrounds the artist’s effort. Integral to the background is the interaction of mythology and hero cult. Very often the scholarship avoids the importance of hero cult in the interpretation of vase paintings. Gregory Nagy unequivocally contests such an approach:

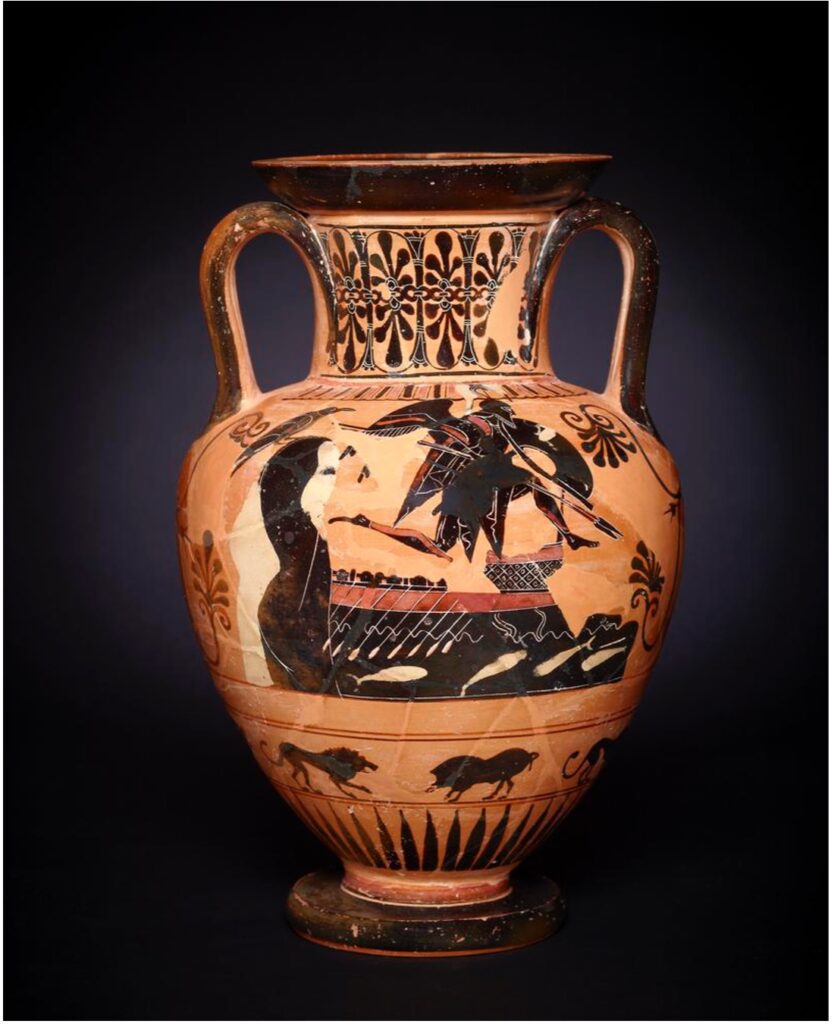

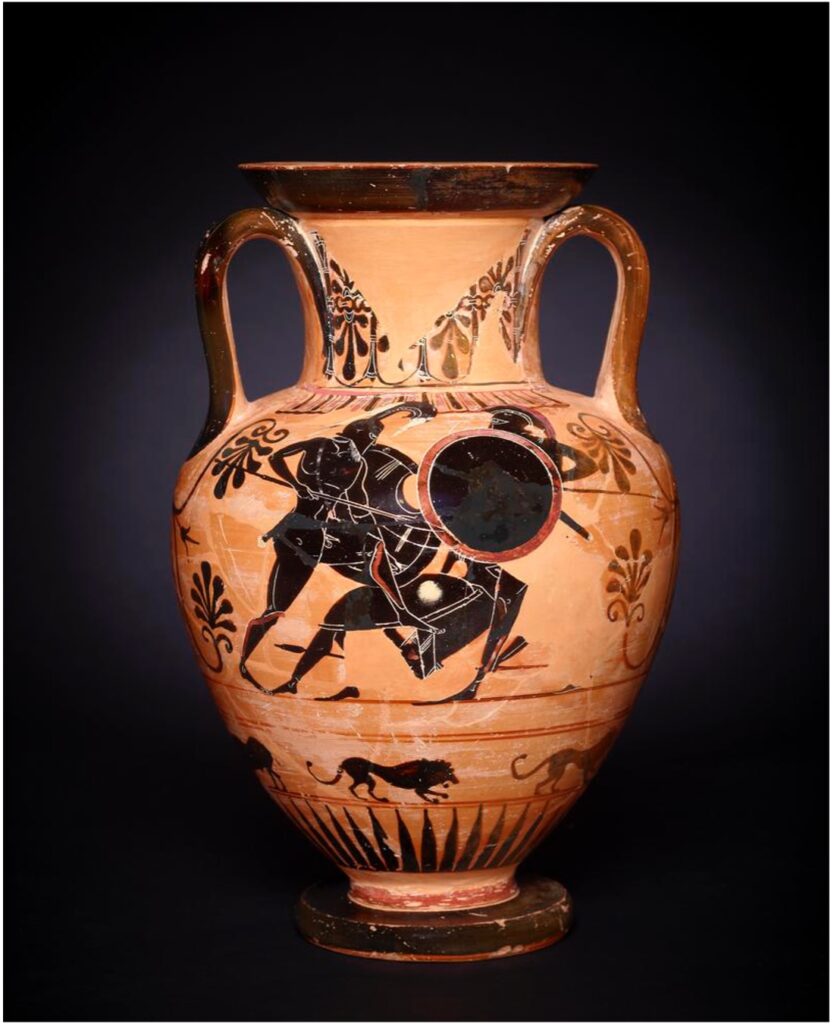

What seems to be specific references are not indicative of direct quotation by the vase painter. Iconographic, metaphoric, and metonymic references are sourced from the ambient culture at large. [4] Drawing on the ambient culture, the vase painter enacts, by using the iconography, an evocation of the cult hero. Given the dating of the vase to around 500 BCE, the painting visually invokes the hero Achilles to assist Athens in supporting its allies rising up against Persia at the time of the Ionian Revolt. This is the contemporary relevance and urgency of the vase painting. Viewed synoptically every component on both the obverse and reverse together reinforces this interpretation.

1§6. Invoking the gods or heroes for support was commonplace in the face of an imminent threat. Herodotus attests to several invocations of and interventions by both epichoric and Panhellenic heroes, especially those from the Trojan War. No example is more dramatic than before the battle of Salamis:

Before the sea battle in 480 BCE the Athenians sent to Aegina to bring the Aiakidai to Salamis (likely in the form of their agalmata) and to enlist them in their fight against the Persian fleet. The invocation occurs as a matter of course in the campaign. Herodotus’s account of the ensuing battle attests to the intervention of Ajax on behalf of the Greek fleet. [6] Upon their victory Themistocles, the presiding Athenian commander, dedicated one of the captured Persian ships to Ajax (Histories 8.121). His account vividly attests to the perceived agency and power of hero cult during this time frame. It also attests to the reciprocal relation between the parties.

1§7. On my reading, this vase-painting on B 240 should be interpreted as an invocation of Achilles to aid the Greeks in the broader context of the Persian threat in the late 6th century/early 5th century. Achilles himself might even have satisfied the Athenian invocation from Themistocles of the Aiakidai at the battle of Salamis. Aiakos was the grandfather of both Ajax and Achilles. In the Iliad Achilles is identified twenty four times with the epithet “grandson of Aiakos.” And Pindar frequently includes Achilles as a son of Aiakidai. In Pythian 8.98-100 (after 446 BCE) he specifically invokes Achilles in the roll call of the Aiakidai (this time for the aid of the Aeginetans):

πόλιν τάνδε κόμιζε Δὶ καὶ κρέοντι σὺν Αἰακῷ

Πηλεῖ τε κἀγαθῷ Τελαμῶνι σύν τ᾿ Ἀχιλλεῖ.

The relationship at the time between Aegina and Athens was fraught. In fact, their rivalry often involved claims on the Aiakidai. Both could and did invoke one or another of the sons of Aiakos. Another time Pindar calls Achilles οὖρος Αἰακιδᾶν, the guardian (or favorable wind!) of the Aiakidai (Isthmian 8.55). But the larger point is not just that one or another polis claimed a degree of their primogeniture for the sake of legitimacy and self-fashioning, but that they both almost reflexively invoked the Aiakidai to intervene against contemporary threats.

2§. Iconography of the Eidōlon

2§6. That the figure is usually winged on vase paintings is another characteristic distinct from an eidōlon in epic. When the deceased Patroclus appears to Achilles there is no mention of his psychē being winged. From where might the winged figure in vase-paintings have developed? I would suggest that the winged figure that appears in death scenes on vase-paintings is an artist’s visual interpretation of the metaphor which occurs in epic for the psychē departing the body. Recall Homer’s metaphor at Hector’s death (Iliad 22.362):

Ὣς ἄρα μιν εἰπόντα τέλος θανάτοιο κάλυψε,

ψυχὴ δ᾿ ἐκ ῥεθέων πταμένη Ἄιδόσδε βεβήκει,

ὃν πότμον γοόωσα, λιποῦσ᾿ ἀνδροτῆτα καὶ ἥβην.

So having spoken, the finality of death covered him

and his psychē having flown from his limbs went to Hades

bewailing his fate, leaving behind his manliness and youth.

At his death Hector’s psychē flies from his limbs to Hades. πταμένη is the aorist middle participle of πέτομαι, to fly, and is etymologically related to πτερόν, feather or wings. In vase paintings, Emily Vermeule identifies this departing psychē as a “soul-bird”. [16] Birds in the vicinity of a death or funereal scene have a long pedigree in Greek vase-painting. They appear on late Geometric funeral vases (circa 750 BCE) in friezes and adjacent to pyres (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248904). On a Protoattic “Nessos” amphora at the Metropolitan Museum (11.210.1) from around 660 BCE Heracles is depicted slaying the centaur. Above the struggling Nessos a bird appears to be departing (https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/248578). The iconography is nearly as old as the earliest figurative scenes on Greek vases, and I would suggest that the birds in some of these circumstances anticipate the eidōlon on late archaic vases. The metaphor was likely traditional in both verbal and visual culture. In some single combat scenes over a fallen hero, a bird in lieu of an eidōlon of the fallen warrior flies between the combatants (http://www.beazley.ox.ac.uk/record/671E9F06-D47A-467B-BB18-D87E28E0D314)(2§25). There is a later red-figure column krater in the British Museum, 1772,0320.36, (https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1772-0320-36-), that makes this equivalence explicit. The scene is the death of Prokris, from whose dying body a bird departs. While stylistically different from the late black-figure eidōlon, the artist depicts the head of the bird with a human face individualized in such a way that it matches the deceased.

2§19. The most complete surviving version of the myth is to be found in Euripides Hecuba (424 BCE). At the play’s opening the eidōlon of Polydorus, son of Priam and Hecuba, whom they believed to be sheltered by King Polymēstor, appears before the audience and explains that the Achaean fleet sits idle on the Thracian coast unable to depart for home. Achilles, he reports, appeared to them above his tomb to demand the sacrifice of Polyxena (Polydorus’s sister) as his “unique prize” γέρας (35-41). This point is then repeated in the course of the play by the Chorus Leader to Hecuba, Polyxena’s mother (106-117), and by Odysseus (389-90). While her mother protests, laments and grieves, Polyxena expresses that she is a willing victim, as death is better than slavery (342-378). Finally, once the sacrifice has been carried out, the herald Talthybius reports the event to Hecuba, quoting Neoptolemus’s address to Achilles while conducting the sacrifice (534-541):

ὁ δ᾿ εἶπεν· Ὦ παῖ Πηλέως, πατὴρ δ᾿ ἐμός,

δέξαι χοάς μοι τάσδε κηλητηρίους,

νεκρῶν ἀγωγούς· ἐλθὲ δ᾿, ὡς πίῃς μέλαν

κόρης ἀκραιφνὲς αἷμ᾿ ὅ σοι δωρούμεθα

στρατός τε κἀγώ· πρευμενὴς δ᾿ ἡμῖν γενοῦ

λῦσαί τε πρύμνας καὶ χαλινωτήρια

νεῶν δὸς ἡμῖν †πρευμενοῦς† τ᾿ ἀπ᾿ Ἰλίου

νόστου τυχόντας πάντας ἐς πάτραν μολεῖν.

Then he said, ‘Son of Peleus, my father,

accept these appeasing drink offerings from me,

elicitations of the dead; come, so you may drink the dark

unmixed blood of the maiden, which we, the army

and I, give to you; be propitious to us

and free the sterns and mooring cables of our

ships, and grant to us a favorable return

from Ilium that all happen to reach their paternal land.

While the ghost of Polydorus and the Chorus Leader, and later, Odysseus (303-320), insist that the epiphany of Achilles is to demand his γέρας (for services rendered), Neoptolemus’s address directly to Achilles makes plain the ongoing reciprocity of hero cult. He expects that Achilles will repay the Achaeans for her sacrifice with clear sailing. The first example, the Berlin hydria, F1902, is not inconsistent with Euripides’s version of the myth. Achilles’s ghost has demanded Polyxena’s sacrifice, and when his son Neoptolemos delivers her, he expects reciprocity from his cult hero father. As in Euripides’s play, she approaches the sacrifice willingly. The inclusion of the three accompanying warriors indicate the larger interest of the expedition and the anticipated reciprocity of their homecoming requested from Achilles for the sacrifice. (Eduard Gerhard in 1852 and Carl Robert two decades later, who were among the first to interpret B 240, suggested that the scene depicted Achilles’s eidōlon coming to stop the fleet departing Ilium until they had sacrificed Polyxena to him (see appendix 9§2-4)).

3§. Iconography of Islands

3§4. The predominant color of all these curvilinear masses is black (red in the case of red-figure), though a few have white accents, which serve to outline the object and distinguish it from adjacent features. White blotches perhaps indicate the island’s or rock’s ruggedness. Looking at the form alone, the black and white object on B 240 clearly belongs within this iconography of islands. But the extent of white on the rendering of the island on B 240 expands the iconography. White glaze or slip comprises over half the form. What on other vases is a mere outline or accent, is here the predominant feature of the island. This variation from tradition suggests the artist deliberately rendered the island to make a specific reference. If so, the obvious interpretation is that this island object on B 240 is Leuke, the White Island, the site of Achilles’s afterlife, as first attested in the Aethiopis, a part of the epic cycle attributed to Arctinus of Miletus:

3§8. On the other hand Strabo noted that in Homer’s day the Euxine Sea itself, which he called the Pontic Sea, was regarded as a second Oceanos, beyond the inhabited world:

Even had a Leuke Island in the Euxine Sea been known to the poet of the Aethiopis and the early oral tradition, regardless of when the poem was written down, it would have been considered a place apart beyond the inhabited world.

4§. Achilles as Cult Hero of Sailors

4§1. In arguing that the vase painter intended the island on B 240 to signify Leuke, Achilles’s afterlife role as a cult hero for sailors comes into play. In the composition of the vase-painting on B 240 the super-sized winged warrior shares the center of the frame with the ship. Here they are inexorably connected. But the hero clearly is the primary agent in the action. Like the unique island iconography the ship functions in a primary synoptic role and provides clues for the hero’s engagement. It also contributes secondarily to the identification of the hero as Achilles. That Achilles was worshipped by sailors requires some unpacking. A cult hero’s efficacy is usually narrowly circumscribed around his sēma or some other shrine. In the case of Achilles his cult efficacy is more expansive. Traces of this cult worship is subtly referenced in Homer. Nagy argues [60] that Iliad 19.373-386 alludes to his cult status for sailors in the scene in which he puts on his new armor from Hephaestus:

εἵλετο, τοῦ δ᾿ ἀπάνευθε σέλας γένετ᾿ ἠύτε μήνης.

ὡς δ᾿ ὅτ᾿ ἂν ἐκ πόντοιο σέλας ναύτῃσι φανήῃ

καιομένοιο πυρός, τότε καίεται ὑψόθ᾿ ὄρεσφι

σταθμῷ ἐν οἰοπόλῳ· τοὺς δ᾿ οὐκ ἐθέλοντας ἄελλαι

πόντον ἐπ᾿ ἰχθυόεντα φίλων ἀπάνευθε φέρουσιν·

ὣς ἀπ᾿ Ἀχιλλῆος σάκεος σέλας αἰθέρ᾿ ἵκανε

καλοῦ δαιδαλέου· περὶ δὲ τρυφάλειαν ἀείρας

κρατὶ θέτο βριαρήν· ἡ δ᾿ ἀστὴρ ὣς ἀπέλαμπεν

ἵππουρις τρυφάλεια, περισσείοντο δ᾿ ἔθειραι

χρύσεαι, ἃς Ἥφαιστος ἵει λόφον ἀμφὶ θαμειάς.

πειρήθη δ᾿ ἕο αὐτοῦ ἐν ἔντεσι δῖος Ἀχιλλεύς,

εἰ οἷ ἐφαρμόσσειε καὶ ἐντρέχοι ἀγλαὰ γυῖα.

τῷ δ᾿ εὖτε πτερὰ γίγνετ᾿, ἄειρε δὲ ποιμένα λαῶν.

In this rich passage Achilles’s new shield is compared to a bright moon and a beacon for sailors. Both the moon and burning fire on a hillside assist ships navigating at night or caught in the darkening clouds of a storm. The threats to the sailors are underscored by the phrase “on the fish-teeming sea,” πόντον ἐπ᾿ ἰχθυόεντα. In epic and in vase painting iconography fish are indicative of the dangers sailors face (see below §5.1-5). And suggestive of the eidōlon on B 240, Homer even sings that his re-arming so pleases Achilles that the arms “become like wings to him” (19.386), τῷ δ᾽ εὖτε πτερὰ γίγνετ᾽.

4§5. Achilles’s cult hero status on the island of Leuke was a natural association for Milesian merchant sailors. As noted above, (3§9-10) the island served as a refuge for ships going to and from their trading posts along the northwest coast of the Euxine Sea. The later Hellenistic literary testimony is abundant in this regard. Arrian (Periplus 21-23) specifically identifies the island as a shelter from the storm overseen by Achilles. The Periplus (131 CE) was a report to Hadrian on the condition of ports around the Euxine Sea, and though he did not himself visit the island, he transmitted to Hadrian what he had learned from sailors familiar with Leuke. Some sailors, he reports, came to port there specifically to offer sacrifices to Achilles. Arrian adds that these brought sacrificial victims with them, but that those who arrived unwillingly, driven off course by a storm, negotiated with the oracle (χρησμοὺς) on the island the price of their rescue (22). He continues (23):

Achilles’s benevolence to sailors is comparable to that of the Dioscuri. The twins and Achilles appear ἐναργεῖς “in bodily form” above masts. Sailors perceive his epiphany either asleep in a dream or awake, and benefit from his agency. On B 240 the over-scaled eidōlon of Achilles is darting above the prow of the ship. Both the ship and the hero are heading in the same direction. As noted above the threat is outside the frame. But in his role as cult hero he is apparently coming to their aid. Around the northwestern Euxine Achilles was identified as Pontarchos, ruler of the Pontus, that is, the Euxine Sea. [65]

5§. Contributing iconography

5§4. When Odysseus finally returns and approaches his father, Laertes does not recognize him and he laments his son’s likely death to the apparent stranger. The underlying basis of this fear is visceral to the audience (Odyssey 24.287-96). It is not merely a fear of death, but the fear of the the loss of proper funeral rites for both the victim and his family:

πόστον δὴ ἔτος ἐστίν, ὅτε ξείνισσας ἐκεῖνον

σὸν ξεῖνον δύστηνον, ἐμὸν παῖδ᾿, εἴ ποτ᾿ ἔην γε,

δύσμορον; ὅν που τῆλε φίλων καὶ πατρίδος αἴης

ἠέ που ἐν πόντῳ φάγον ἰχθύες, ἢ ἐπὶ χέρσου

θηρσὶ καὶ οἰωνοῖσιν ἕλωρ γένετ᾿· οὐδέ ἑ μήτηρ

κλαῦσε περιστείλασα πατήρ θ᾿, οἵ μιν τεκόμεσθα·

οὐδ᾿ ἄλοχος πολύδωρος, ἐχέφρων Πηνελόπεια,

κώκυσ᾿ ἐν λεχέεσσιν ἑὸν πόσιν, ὡς ἐπεῴκει,

ὀφθαλμοὺς καθελοῦσα· τὸ γὰρ γέρας ἐστὶ θανόντων.

Laertes’s lament highlights the true terror for those dying at sea. He directly links such a death , and the corresponding loss and mutilation of the corpse, to the loss of a proper burial, the γέρας of mortals which is due not only to the hero, but the hero’s family. A similar mutilation and loss of proper burial is also what Hector repeatedly tries to circumvent in his waning dialog and plea to Achilles, but which Achilles refuses to grant, telling Hector, ἐνταυθοῖ νῦν κεῖσο μετʼ ἰχθύσιν, οἵ σʼ ὠτειλὴν / αἷμʼ ἀπολιχμήσονται ἀκηδέες, “lie there among the fish who, uncaring, will lick the blood from your wound” (Iliad 21.122-3).

5§5. This intersection of the danger of seafaring and the terror of dismemberment by fish persists in the Greek Anthology. Quite a number of epigrams echo this fear of this fate: 7.274; 7.276; 7.278; 7.286; 7.288. That of Leōnidas is typical (7.273):

καὶ νύξ, καὶ δνοφερῆς κύματα πανδυσίης

ἔβλαψ᾿ Ὠρίωνος· ἀπώλισθον δὲ βίοιο

Κάλλαισχρος, Λιβυκοῦ μέσσα θέων πελάγευς.

κἀγὼ μὲν πόντῳ δινεύμενος, ἰχθύσι κῦρμα,

οἴχημαι· ψεύστης δ᾿ οὗτος ἔπεστι λίθος.

The last two lines get to the point poignantly: at sea Leōnidas became prey for fish, and the epigram reminds the viewer visiting his tomb that the tomb marker itself is a falsehood, that he never had a proper burial.

5§9. The birds’ behavior on Leuke has a parallel on Islands of Diomedes (Isole de’ Tremiti) in the Adriatic Sea. D’Arcy Thompson, based on this same behavior of wetting their wings and cleaning a shrine identifies the species there as αἴθυιαι, shearwaters. [76] There they were said to be Diomedes’s companions who were killed by invaders from the mainland and whom Zeus transformed into birds. Recall Arrian included shearwaters on Leuke. Perched on an outcrop a shearwater and a cormorant have a similar silhouette. However, a shearwater has a light underside, while a cormorant’s is darker. The bird on B 240 is predominantly black, with only a few white accents at its wingtips. Neither are white as Philostratus describes, but from below a shearwater in flight might appear to be white. For the sailors, both the shearwater and the cormorant were, like Pollard’s raven, foreboding. Again an epigraph from the Greek Anthology, 7.285, shows how:

ἣν ἐσορᾷς αὕτη πᾶσα θάλασσα τάφος·

ὤλετο γὰρ σὺν νηΐ· τὰ δ᾿ ὀστέα ποῦ ποτ᾿ ἐκείνου

πύθεται, αἰθυίαις γνωστὰ μόναις ἐνέπειν.

Like fish, the sea birds’ foreboding includes a loss of proper burial rites. From Artemidōros, Oneirocritica 2.17 we learn that “Gulls, cormorants, and other maritime species portend great peril for sailors but not their death, since these birds can submerse without drowning in the sea…They also indicate that things lost will not be recovered, since these birds gulp down whatever they get hold of.” [77] For sailors the final result is the same. Lost at sea, they will not receive a proper burial.