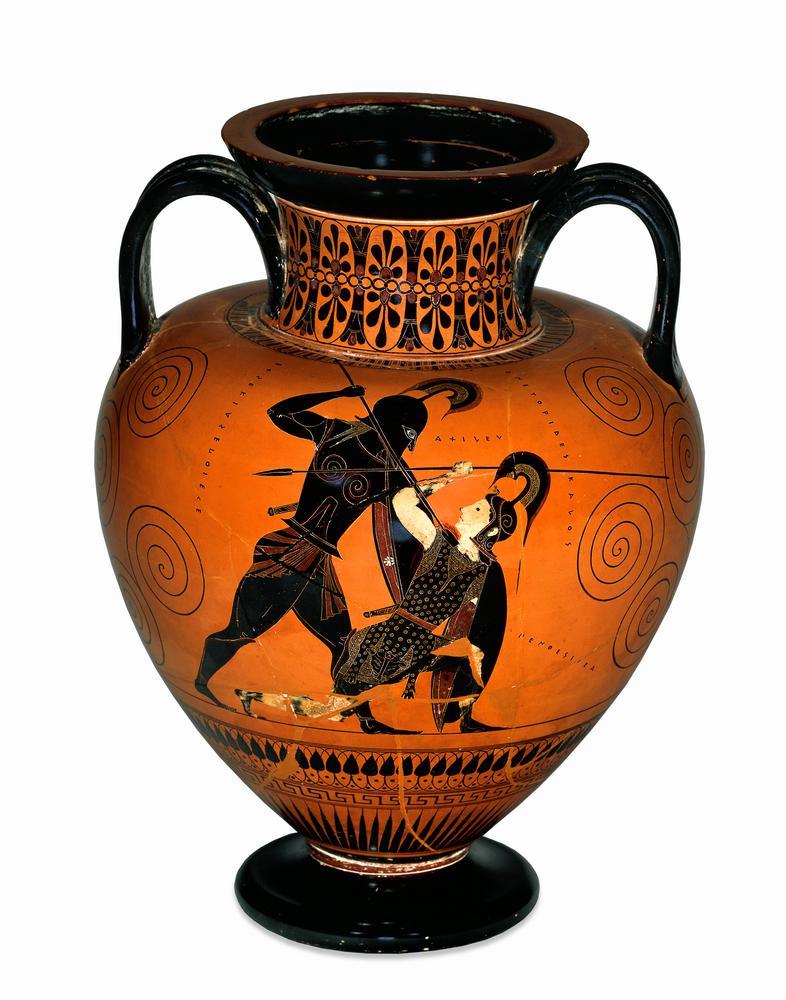

2022.06.13 | By Gregory Nagy

§0. The featured image for Phase 5 is a close-up of the face of a dying Amazon. She is Penthesileia, daughter of the war-god Ares. The close-up comes from an ancient Athenian vase painting that pictures this female hero, an Amazon, at the moment of her death, killed by the male hero Achilles, with whom she is engaged in mortal combat, one-on-one. And, at this precise moment of death, the Amazon looks up at her killer, Achilles, while he, in turn, is looking down at her. As their eyes meet, Achilles falls in love with Penthesileia, but now it is too late: a fatal wound is about to penetrate the beautiful body of the Amazon. In my book about ancient Greek heroes, H24H 3§§4–9, I comment on this deadly erotic moment, which must have been highlighted in the epic Aithiopis, attributed to the poet Arctinus of Miletus (plot-summary by Proclus p. 105 lines 22–26 ed. Allen 1912). And I argue there that Achilles and Penthesileia are heroic body-doubles of each other—one male and one female. Here in this book on ancient Greek heroes, athletes, and poetry, I now refine the general description I just gave, “heroic,” since Penthesileia, as an Amazon in epic, is not only a hero in general. As I have just argued in Phases 2 and 3 of my Introduction, where I compared what we know about this Amazon with what we know about other Amazons, Penthesileia must have been also a cult-hero in particular—just as Achilles and other such he-warriors in epic were also cult heroes. Despite such a parallelism between the she-warrior Penthesileia and the he-warrior Achilles as cult heroes, however, I must note also a basic non-parallelism that sets this pair forever apart: unlike Achilles, who was primarily a warrior, the Amazon Penthesileia was primarily a hunter. Only for special tragic reasons, as we saw in Phase 3 of the Introduction, did she become primarily a warrior. And Penthesileia had once been primarily a hunter precisely because she was and is and always will be an Amazon. Further, since Amazons as hunters are modeled on the goddess Artemis, who is the ultimate hunter, the sexuality that we see implied in the Death Scene where Achilles kills Penthesileia signals, tragically, the unavailable eroticism of Artemis, not the ever-available eroticism of Aphrodite. Such a tension between sexual availability and unavailability, as we saw in Phase 4, goes to the heart of the myth about the unrequited love of the queen Phaedra for her step-son Hippolytus the hunter, whose genealogy as the son of an Amazon even makes him a lookalike of the goddess Artemis herself. Thus the erotic longings of Phaedra, as verbalized in the poetry of Euripides, are doomed from the start. For Phaedra to long for self-identification with Hippolytus the hunter is to be longing for the unavailable sexuality that we see embodied in the goddess Artemis. Such longing, in the Hippolytus of Euripides, leads to Phaedra’s doom, of course, just as the longing of Hippolytus himself to stay forever in the company of Artemis leads to his own doom. And what is thus illuminated about Artemis here in the poetry of Euripides is relevant, as we will now see in Phase 5, to something elemental about Amazons in general, not only about Penthesileia in particular: Amazons are all modeled, erotically and all too tragically, on the ideal of Artemis the Hunter.

§1. Masters of art in the ancient Greek world—I am thinking here of verbal as well as visual arts—seem preoccupied with picturing Amazons engaged in hunting, which is after all the most exquisite delight in life for these female heroes. And the divine model of Amazons as hunters, the goddess Artemis, takes her own delight in hunting. I think of the celebrated “Hunting Cantata” of Johann Sebastian Bach (BWV 208; première 1713), where the soprano Artemis/Diana leads off, singing: “Was mir behagt, ist nur die muntre Jagd!” I translate: “What delights me is the lively hunt—nothing else” (https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yc_btdk-_d4). As we have seen in Phase 3, a shining illustration of Amazons engaged in their lively hunt is the Edessa Mosaic, which pictures a veritable choreography of four hunting Amazons in a wide variety of poses that show off their athleticism. And, as we have also seen, a special feature of the athletic bravura that is being shown off by such Amazons is their prodigious skill in shooting arrows or in casting javelins while they ride on horseback. Woman and horse, speeding woman mounted on speeding horse, the two together are exquisitely synchronized in motion as they chase after her prey and as she takes aim at her moving target.

§2. Such a linking of Amazons with horses, of horses with Amazons, is I am sure a most ancient idea—an idea we find attested, I think, already in the verbal art of Homeric poetry. I have in mind here the wording of Iliad 2.811–815, a passage that pictures an Amazon who is seen in the act of running—but she is not simply running, since she is also exuberantly leaping and bounding as she runs, like some racing horse. Perhaps her motion is synchronized with the running of a racing horse that she is riding. Or perhaps she herself is running like a racing horse. Either way, the imagery is compressed into a single word. The word, as we read it at Iliad 2.814, is polú-skarthmos, a compound adjective used here as an epithet that describes a speeding Amazon, and I propose to translate this epithet as ‘speeding ahead with many leaps and bounds’. The Amazon who is described by way of this epithet polú-skarthmos at line 814 here in the Homeric Iliad is named Múrīna / Murī́nē (πολυσκάρθμοιο Μυρίνης). I will hereafter write her name simply as Murinē. In Homeric diction, the same element skarthmós that we see embedded in the Amazon’s epithet—the element that I render as ‘leaping and bounding’—is built into another Homeric compound adjective, eú-skarthmoi, which I translate as ‘beautifully leaping and bounding’, which is an epithet that describes the divine horses that draw the chariot driven by the lord of horses himself, the god Poseidon, as we see in Iliad 13.31 (ἐΰσκαρθμοι … ἵπποι). The verb from which these epithets are derived, skaírein, is conventionally translated as ‘skip’ or ‘dance’ or ‘frisk’.

§3. But this Amazon Murinē, so lively in her speeding athleticism as she is seen leaping and bounding ahead, is no longer alive in Iliad 2.811–815. Despite what her epithet says about her—that she is ‘speeding ahead with many leaps and bounds’—she is now dead. And she is not only dead, she is a cult hero. Her body is hidden underneath the earth somewhere inside a tumulus—I am using here a term frequently used by archaeologists in referring to a prominent mound of earth—which is the site of her tomb, and, at this tumulus, we see her being worshipped as a cult hero by the people of Troy. That is how I interpret Iliad 2.811–815 in a cumulative Homeric commentary of mine (Nagy 2016–2022). The word kolōnē here at line 811, which I will translate simply as ‘tumulus’, refers to the place where, as we read further at line 814, the sēma ‘tomb’ of the Amazon named Murinē is located. We may compare the word kolōnē ‘tumulus’, as used here in the Homeric Iliad, with the word kolōnos ‘tumulus’ referring to the tomb of the cult hero Protesilaos in Philostratus On heroes 9.1. (In Hour 14 of H24H, I offer extensive commentary on this hero Protesilaos and on the relevant work of Philostratus, On heroes, dated to the early third century CE.) Elsewhere in On heroes, at 9.3, this same tomb of the cult hero Protesilaos is called a sēma ‘marker’—in the sense of ‘tomb’. Also, the same word kolōnos ‘tumulus’ refers to the tomb of Achilles himself in On heroes 51.12 (also at 53.10, 11). This tomb of Achilles, which marks the site on the Hellespont where he is worshipped as a cult hero, is also called a sēma in On heroes 53.11 (also 51.2, 52.3; further analysis in H24H 14§§23–26).

§4. In the Homeric passage about Murinē in Iliad 2.811–815, she is not described explicitly as an Amazon, but her Amazonian identity is amply documented in two historical sources, Diodorus of Sicily, first century BCE, and Strabo the Geographer, first century BCE/CE. Both sources report on a wide variety of regional variations in the transmission of myths about Murinē the Amazon: Diodorus at 3.54.2 through 3.55.11 and Strabo at 11.5.4, 12.3.21, 12.8.6, 13.3.5–6. For now I simply focus on one particular detail about her cultural identity: Murinē is linked to the Aeolian populations who lived in mainland Asia Minor and on the offshore island Lesbos. Her name even becomes synonymous with a mainland Aeolian city, Murinē, while she has a sister, named Mutilēnē=Mytilene, whose own name becomes synonymous with the dominant city on the island of Lesbos, Mytilene.

§5. Having made a case for viewing this Homeric passage about Murinē in Iliad 2.811–815 as one of the earliest attestations of ancient Greek hero cult, I will now argue that Murinē is comparable to the Amazons who are worshipped, according to historical sources, as cult heroes at tombs where they are believed to be buried. In Phase 3, I have highlighted three such Amazons whose tombs are mentioned by Pausanias: Antiope, Molpadia, Hippolyte. And I will also agree that the epithet of Murinē in Iliad 2.811, polú-skarthmos, ‘speeding ahead with many leaps and bounds’, is indirectly relevant to these three Amazons in particular and even to Amazons in general.

§6. The Amazon Murinē is lively in her life inside her epithet polú-skarthmos ‘speeding ahead with many leaps and bounds’ at Iliad 2.811, and I ask myself: what if the Amazon’s life was cut short in the act of leaping and bounding? And, if so, how could such an interruption be pictured in the verbal arts—or in the visual arts? If such a picturing could stop her motion, even for a moment, in a kind of cinematic freeze-frame, we could then imagine our Amazon as ascending to the very highest point in her arc of leaping. And, as we will see in what follows, such a stop-motion-picture of an Amazon is actually attested in the visual arts of classical Athenian sculpture.

§7. For the moment, though, I must turn to the testimony of Pausanias, who makes a passing mention at 1.17.2 about the picturing of a famous mythological scene: it is the Battle of the Athenians and Amazons, known in other ancient sources as the Amazonomakhiā ‘Amazonomachy’. Pausanias at 1.2.1 and at 1.15.2 already makes reference in those earlier passages to the fighting between the Amazons and the Athenians as led by their hero-king Theseus. And here at 1.17.2, Pausanias also mentions a picturing of the Amazonomachy by the Athenian artist Pheidias, contemporary and protégé of the Athenian statesman Pericles.

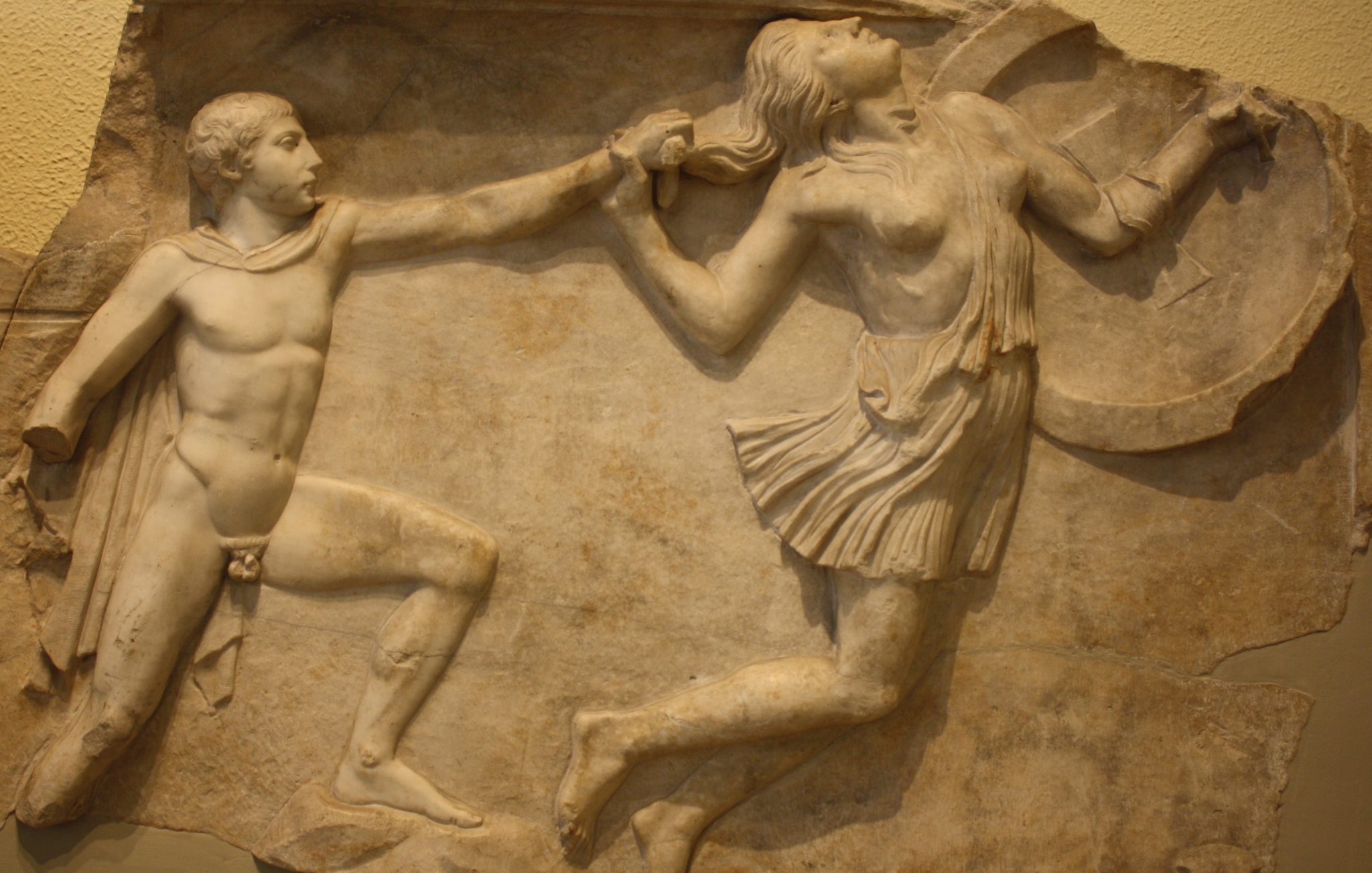

§8. For an illustration, I show here a close-up of a detail from the Amazonomachy as originally pictured by Pheidias in the fifth century BCE. The artist had metalworked the whole scene of the Amazonomachy into the shield of a colossal statue of Athena that was once housed in the Parthenon on the acropolis of Athens. As for the detail that I am showing here, it comes from the so-called Peiraieus Reliefs, dating from the second century CE, which replicate faithfully what was pictured in the Amazonomachy of Pheidias in the fifth century BCE. We see in this detail a fleeing Amazon whose head is violently jerked backward by a pursuing Athenian who has grabbed from behind the woman’s hair, which has come undone and is flowing luxuriantly in the air:

§9. What we see here in the second picture, which zooms out from the first picture, is beautiful but disturbing. The picturing of the violence inflicted on the woman by the man offends our contemporary sensibilities, but, then again, the whole myth of the Amazonomachy is difficult in and of itself for us to understand.

§10. I find a comparable difficulty in the vase painting that I showed at the start, where we see the picturing of the Amazon Penthesileia being killed by Achilles—and where the picture is not only aestheticized but even eroticized. Here is another ancient example of such a picture:

And here is a modern reworking:

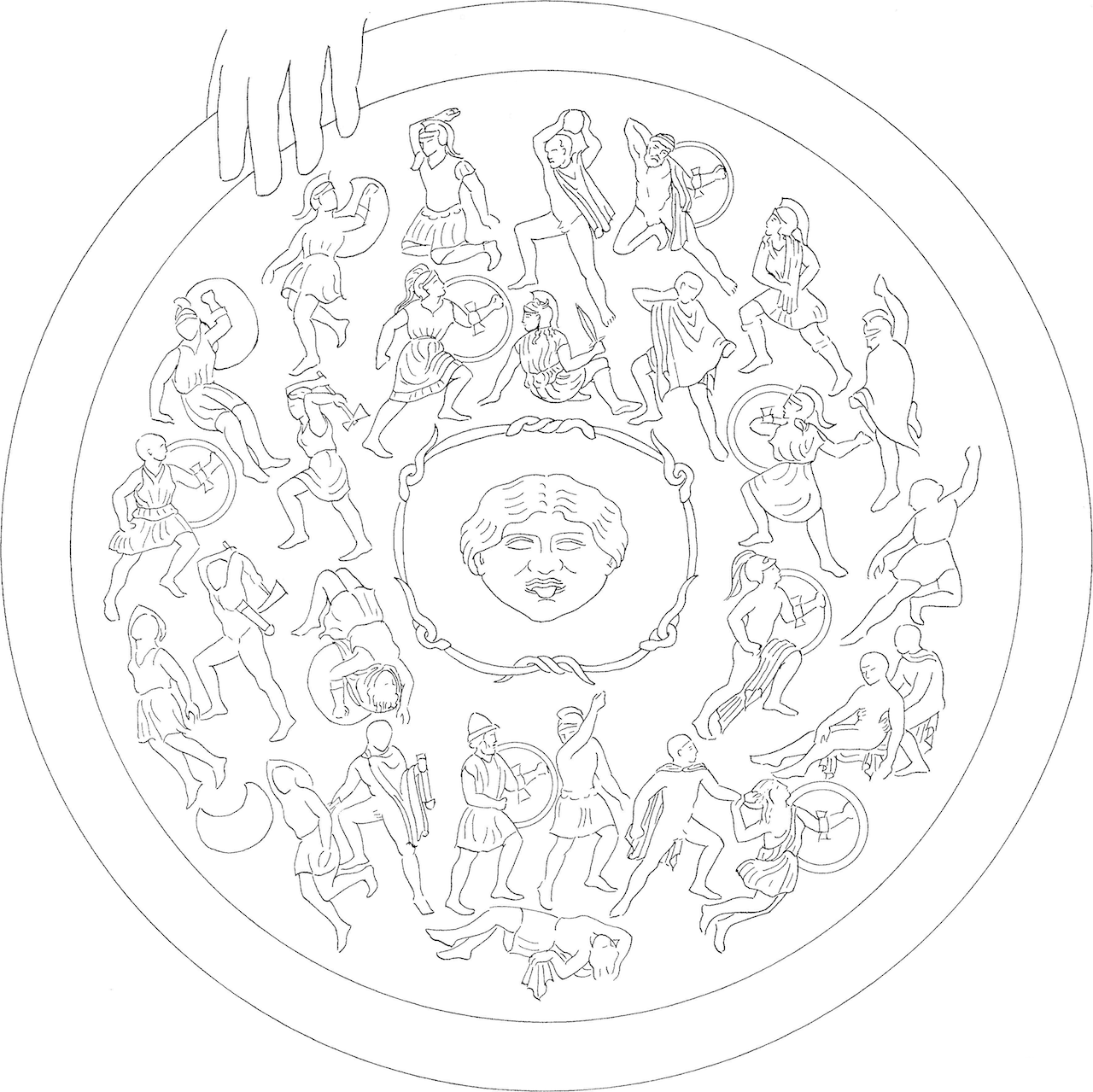

§11. I close by commenting further on the death of one Amazon as pictured by Pheidias in his masterpiece of metalwork. This is where, as I showed above, the Amazon is yanked back by the hair as she reaches the highest point in the arc of a graceful leap. And I show two relevant pictures where, this time, the perspective zooms out. The first picture is a line drawing that reconstructs the whole world of images that had been metalworked by Pheidias into the convex surface of Athena’s Shield. And the second picture is a close-up color photograph showing the reconstructed Athena-with-Shield as housed in Nashville, Tennessee. Featured there on the surface of the Shield is the narrative of the Battle of Athenians and Amazons in all their metallic glory. I find it most moving, somehow, to see the ivory fingers of the goddess as they make contact with the upper rim of her gigantic metal Shield. Both in the line drawing and in the color photograph, you get a good view of Athena’s white fingers poised over the action of the battle that is ongoing below. And, if you look closely in both pictures, you can see at the lower right corner of Athena’s Shield that striking detail from the Amazonomachy where the beautiful Amazon with the flowing hair, in her stop-motion choreography of death, is forever prevented from leaping forward and reclaiming her freedom from domination by men.

Bibliography

Allen, T. W., ed. 1912. Homeri Opera V (Hymns, Cycle, fragments). Oxford.

Barrett, W. S., ed., with commentary. 1964. Euripides, Hippolytus. Oxford.

Blok, J. H. 1995. The Early Amazons: Modern and Ancient Perspectives on a Persistent Myth. Leiden.

Dowden, K. 1997. “The Amazons: Development and Functions.” Rheinisches Museum 140:97–128.

Frazer, J. G., ed. and trans. 1921. Apollodorus: The Library. 2 vols. New York. https://archive.org/details/library00athegoog.

Jones, W. H. S., trans. 1918. Pausanias, Description of Greece I–X (II: with H. A. Ormerod). Cambridge, MA.

Loosley, E. 2018. “Cultural Imperialism at the Borders of Empire: The Case of the ‘Villa of the Amazons’ in Edessa.” Journal of Semitic Studies Supplement Series No. 41: Near East and Arabian Essays – Studies in Honour of John F. Healey (ed. by G. J. Brooke, A. H. W. Curtis, M. al-Hamad, and G. R. Smith) 215–229. Oxford. https://ore.exeter.ac.uk/repository/bitstream/handle/10871/31470/Mosaic%20article.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y.

Maehler, H., ed. 1980. Pindari Carmina cum fragmentis / post Brunonem Snell. 6th edition. Leipzig.

Mayor, A. 2014. The Amazons: Lives and Legends of Warrior Women across the Ancient World. Paperback 2016. Princeton and Oxford.

Nagy, G. 2008. Homer the Classic. Hellenic Studies 36. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Classic.2008. Print edition 2009.

Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Paperback 2020. Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013.

Nagy, G. 2016–2022. A sampling of comments on the Iliad and Odyssey. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hlnc.essay:Nagy.A_Sampling_of_Comments_on_the_Iliad_and_Odyssey.2017.

Nagy, G. 2017.10.19. “A sampling of comments on Pausanias: 1.1.1–1.2.1.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-pausanias-1-1-1-1-2-1/.

Nagy, G. 2018.01.12. “A sampling of comments on Pausanias: 1.16.1–1.17.2.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-pausanias-1-16-1-1-17-2/.

Nagy, G. 2018.06.14. “Smooth surfaces and rough edges in retranslating Pausanias, Part 1.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/smooth-surfaces-and-rough-edges-in-retranslating-pausanias-part-1/.

Nagy, G. 2018.06.21. “A placeholder for the love story of Phaedra and Hippolytus: What’s love got to do with it?” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/a-placeholder-for-the-love-story-of-phaedra-and-hippolytus-whats-love-got-to-do-with-it/.

Nagy, G. 2018.08.03. “More on the love story of Phaedra and Hippolytus: comparing the references in Pausanias and Euripides.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/more-on-the-love-story-of-phaedra-and-hippolytus-comparing-the-references-in-pausanias-and-euripides/.

Nagy, G. 2018.08.10. “Thoughts about heroes, athletes, poetry.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/thoughts-about-heroes-athletes-poetry/.

Nagy, G. 2020. Second edition of Nagy 2013.

Nagy, G. 2020.08.14. “Death of an Amazon.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/death-of-an-amazon/.

Nagy, G. 2022.01.31. “Pausanias 2.32.3-4, on the hero cults of Phaedra and Hippolytus at Troizen.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/annotation-for-pausanias-2-33-34-on-the-hero-cults-of-phaedra-and-hippolytus-at-troizen/.

Pitt-Rivers, J. 1970. “Women and Sanctuary in the Mediterranean.” Échanges et Communications: Mélanges offerts à Claude Lévi-Strauss (ed. J. Pouillon and P. Maranda) II 862–875. The Hague.