Sappho I, Version Alpha via Beta: Essays on ancient performances of her songs

December 28, 2023; revised December 21, 2024; preprint May 24, 2025

By Gregory Nagy

Preface

This book about the songs of Sappho is one of three interrelated books published online by Classical Continuum in 2023 and revised in 2024 for printed versions published by ΕΠΟΨ Publishers in 2025.

The title of this book, Sappho I, Version Alpha via Beta: Essays on ancient performances of her songs, complements the title of another one of the three books, Sappho II, Version Beta: Essays on ancient imitations of her songs. As for the third book, the content is more introductory, and I have therefore given it a title that is not symmetrical with the titles of the other two books. In that case, the title is, simply, Sappho from ground zero, which I will abbreviate hereafter as Sappho 0, to be contrasted with the titles of the two other books, which I will hereafter abbreviate simply as Sappho I and Sappho II.

By contrast with Sappho 0, the chronological starting-point for Sappho I here is not “zero.” Rather, my starting-point for Sappho I is a time that historians posit as the era of Sappho herself, whom they date at around 600 BCE. This era cannot be considered an absolute starting-point, however. As I argue in Sappho 0, especially in Essay 4 there, the traditions of songmaking exemplified by the received text of Sappho can be reconstructed farther back in time, much farther, than the date posited by historians for Sappho herself, around 600 BCE.

These three books about Sappho can be read independently of each other, though all three, in their online versions as first published in the last month of 2023, are provided with cross-references by way of links. The links also keep track of the older as well as the newer online content of each essay. Even in the printed versions of these three books, cross-references to online content—newer or older—are retained.

Wherever I simply cross-refer from one book to another in this set of three books, my format for citation will be in short-hand: Sappho 0, Sappho I, Sappho II. For readers of the printed versions of these three books, I should add that none of them needs an Index, since the corresponding online versions, all three of which are available gratis via https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu, are completely “searchable.”

Also, I need to comment on a special feature of the present volume, Sappho I. I occasionally cite here a few publications that are dated after 2023, the year of my original online publication. For example, I list in my Bibliography a book by Melissa Muller, Sappho and Homer: A Reparative Reading, published in the first half of the year 2024. The author not only presents an engaging synthesis of her own interpretations of Sappho as compared with “Homer.” More than that—and this is most helpful to me—she also manages to keep track of an extraordinarily wide range of alternative interpretations that are not tracked in my own Bibliography here. I recommend her book especially to readers who are looking for a wider view of the many interpretations that have more recently been published. By contrast with her book, though, my three books on Sappho are far more sparing in citations of alternative views, especially where the authors of such views show little interest in matters of primary concern to me.

Finally, I take this opportunity to pay homage to five extraordinarily collegial friends who have edited with me all three of my books on Sappho. I list these friends here in a sequence that reflects a chronological order of their essential involvement: Claudia Filos, Noel Spencer, Keith DeStone, Arin Jones, and Leonard Muellner.

Introduction: Diachronic Sappho

rewritten from 2015.10.22

0§1. My approach to the songmaking of Sappho is diachronic as well as synchronic—to be contrasted with other approaches taken by some other classicists who seem to be disinterested in diachronic perspectives. In order for me to emphasize the importance of diachronic approaches to Sappho, I have pointedly made a subtitle here for my Introduction, “Diachronic Sappho.”

0§2. Before I say more about diachronic approaches to Sappho, I first offer some general observations about the terms “synchronic” and “diachronic,” taken together. These terms stem from a distinction established by a pioneer in the field of linguistics, Ferdinand de Saussure. For Saussure (1916:117), synchrony and diachrony refer respectively to a current state of a language and to a phase in its evolution. I draw attention to Saussure’s connecting of diachrony with evolution—a connection that has proved to be crucial, over the years, for my analysis of Homeric poetry in particular. And the same connection of diachrony with evolution has also been crucial for my analysis of Sappho’s songmaking. Here I find it relevant to mention again a reference I made, in the Preface, to the book Sappho and Homer, by Melissa Muller (2024), who consistently compares the poetics of Sappho and Homer—but without insisting that the text of Sappho is referring to a text of Homer. To my own way of thinking, then, her comparisons are implicitly diachronic. By contrast, however, most other publications of classicists whom she cites on the general subject of “intertextuality” are clearly devoid of any diachronic perspectives. Major exceptions are essays by Richard P. Martin (2001), whom she cites at her p. 28, and by Olga Levaniouk (2018), cited in passing at her p. 132. My own overall approach comes closest to theirs.

0§3. In my work here on Sappho, as in my work elsewhere on Homer and Sappho, I add two restrictions to my use of the terms synchronic and diachronic. First, I apply these terms consistently from the standpoint of an outsider who is thinking about a given system, not from the standpoint of an insider who is thinking within that system. Second, I use “diachronic” and “synchronic” not as synonyms for “historical” and “current,” respectively. Diachrony refers to the potential for evolution in a structure. History is not restricted to phenomena that are structurally predictable. As for synchrony, a synchronic approach is simply the study of a structure, not of any historical status quo.

0§4. In the formulations I have made so far in 0§§1–3 about synchronic and diachronic approaches, I have drawn most of the content and wording from the first page of a book I wrote about Homer, and I cite it now: it is Homeric Responses, the printed version of which was published in 2003. Here and in the rest of my book, I will be making further such citations, where relevant, from earlier publications of mine. A prime example is an essay published in 2011(b), “Diachrony and the Case of Aesop.”

0§5. Though all such publications are fully listed in the Bibliography for my book here, I have designed a streamlined format for immediate citations I will be making as my argumentation now gets underway. I will be referring to relevant studies of mine by noting simply the dates of publication. I now list here, in chronological order, the dates for publications that are particularly relevant, together with the titles I had previously given to these publications, many of which were originally available only in printed versions:

1973/1990b = “Phaethon, Sappho’s Phaon, and the White Rock of Leukas.”

1974 = GIM = Comparative Studies in Greek and Indic Meter

1979/1999 = BA = The Best of the Achaeans: Concepts of the Hero in Archaic Greek Poetry

1985 = “Theognis and Megara: A Poet’s Vision of His City”

1990a = PH = Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past

1990b = GMP = Greek Mythology and Poetics

1993 = “Alcaeus in Sacred Space”

1994 = “Genre and Occasion”

1995 = “Transformations of Choral Lyric Traditions”

1996a = PP = Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond

1996b = HQ = Homeric Questions

2003 = HR = Homeric Responses

2004 = “Transmission of Archaic Greek Sympotic Songs”

2007|2009 = “Did Sappho and Alcaeus Ever Meet?”

2009/2010 = “The ‘New Sappho’ Reconsidered”

2011a = “Diachrony and the Case of Aesop”

2011b = “The Aeolic Component of Homeric Diction”

2013a = H24H = The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours

2013b = “The Delian Maidens and their relevance to choral mimesis in classical drama”

2015 = MoM = Masterpieces of Metonymy

2015.10.01 = “Genre, Occasion, and Choral Mimesis Revisited”

2015.10.22 = “Diachronic Sappho: some prolegomena”

2015.11.05 = “Once again this time in Song 1 of Sappho”

2015.12.31 = “Some imitations of Pindar and Sappho by Horace”

2015|2016 = “A poetics of sisterly affect in the Brothers Song and in other songs of Sappho”

2017.06.10 = “Diachronic Homer and a Cretan Odyssey”

2018.06.30 = “Sacred Space as a frame for lyric occasions”

2018.12.06 = “Previewing an essay on the shaping of the Lyric Canon in Athens”

2021.11.29 = “On the Shaping of the Lyric Canon in Athens”

0§6. In my book here, Sappho I, the online version provides links embedded in the date of original publication for all but one of the works listed above. The exception is the first work, dated 1973, an article that was rewritten as Chapter 9 of a book of mine listed as Nagy 1990b in the Bibliography below. Where possible, the dating indicates the year/month/day of online publication; otherwise, the dating indicates only the year.

0§7. From here on, whenever I cite these publications, I will refer to them simply by “author’s name”—in this case, “Nagy,” regularly abbreviated as “N”—followed by date of publication. For example, the essay “Diachrony and the Case of Aesop” will regularly be cited simply as N 2011a. On the other hand, in cases where I cite any one of the nine books among the works that I just listed, I will add, as prefixes to the original dates of publication in print, the following abbreviations for their titles: GIM, BA, PH, GMP, PP, HQ, HR, H24H, MoM. Thus for example the book Pindar’s Homer will regularly be cited simply as PH=1990a; in such cases, of course, there is no need for an additional prefixing of N.

0§8. In what follows, then, I will be using this streamlined system of citations as I proceed to track references to my own studies concerning the songmaking of Sappho—with special emphasis on my dual perspective in analyzing the songs of Sappho diachronically as well as synchronically.

0§9. What will become increasingly clear, as the reading progresses, is that the combining of diachronic with synchronic approaches to Sappho’s songmaking can help us see the coherence of her art as an evolving medium. To be contrasted, as I already noted, are single-minded views about Sappho’s poetics in the publications of some experts who seem to avoid any diachronic perspective. What results, I think, from such avoidance is a lack of clarity in viewing Sappho’s medium as it changes through time.

0§10. To make more specific what I mean, I now offer a working inventory of five hypothetical formulations, numbered ABCDE, where I symbolize contrasting views by way of contrasted boldface and non-boldface fonts. In boldface font, I will paraphrase various views that seem to ignore diachronic perspectives, to be countered in non-boldface font by paraphrases of my own views combining diachronic with synchronic perspectives. These paraphrases of mine are based mostly on relevant publications as listed above, many of which I will now be citing below in streamlined format.

A. Sappho wrote poems. I disagree. There is no proof that the composition of songs by Sappho depended on the technology of writing. In N 1974 as also in the Appendix to PH=1990a, I offer proof that a composition like Song 44 of Sappho was created by way of a formulaic language that is cognate with the formulaic language used in the compositions that we know as the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey. Such formulaic language provides evidence for thinking of Sappho’s songmaking in terms of oral poetics. As I summarize in N 2011b:155–156, the songs attributed to Sappho—and, as we will see, also the songs attributed to a male contemporary of hers named Alcaeus—cannot be divorced from the performing of these songs. To put it as simply as possible: the songs of Sappho—and of Alcaeus—were meant to be performed, not read as texts. And here is an additional specific point that I need to make already now: the compositions attributed to Sappho and Alcaeus are not simply poems. They are, as I have been saying already, songs—that is songs meant to be sung. More on this point in what follows.

B. Sappho is a historical person, to be dated around 600 BCE, who intended her songs for other historical persons named or unnamed in the wording of these songs. This formulation is based on assumptions of obvious certainties, but things become less obvious when we stop and think further about what we actually know—and what we cannot know for sure. Before we can speak of what we know about Sappho, we must first ask ourselves this all-important question: for whom were her compositions intended? The answer, as I hope to show in the essays I present in this book here, is that Sappho’s compositions were songs that had been “intended,” ultimately, for the people of Lesbos in general. In other words, these songs were ultimately “intended” not only for, say, some inner circle of women or girls, not only for any sub-group of the population. And I view the concept of “intention” diachronically here, not only synchronically. The persons to whom Sappho speaks in her songs become personae or—let me say it more simply—characters in the world of these songs. So also Sappho—by virtue of speaking (1) to these characters and (2) about these characters and (3) about herself—becomes a character in her own right. The ancient Greek word for the functioning of personalities or personae or characters in the world of song is mimesis, as I argued in N 2015.10.01—rewritten as Essay 5 below. A more extended argument, with reference to Greek songmaking in general, is made in N 2013b.

C. The occasion for the songs of Sappho can be determined by whatever the words of these songs have to say about the world of Sappho. But is there a static world of Sappho? As I hope to show in the essays that follow, the actual occasion for each of Sappho’s songs was determined by the historical circumstances that shaped the traditions of performing the songs—and these circumstances changed over time.

D. The medium of Sappho, in the performance of her songs, was monodic—in other words, the medium was a solo performance of song. As I hope to show, however, Sappho’s songs were choral as well as monodic. When I say choral, I have in mind the general idea of performances by a khoros, conventionally translated as ‘chorus’—though the word in Greek includes dancing as well as singing, whereas the English word excludes dancing. From the start, I offer here a working definition of the khoros ‘chorus’: the Greek chorus is a group of performers who both sing and dance a given song within a space (real or notional) that is sacred to a divinity or to a constellation of divinities. This working definition will be tested and further developed diachronically in the essays that follow. Time and again, the question will arise: how can we tell whether a given song of Sappho is sung as a choral or as a monodic form of singing? From a diachronic point of view, as we will see, both choral and monodic singing were accommodated in the overall repertoire of Sapphic songmaking. If we deprived ourselves of a diachronic point of view, on the other hand, we would be forced to choose, in the case of each song we read, whether its performance had been meant to be either choral or monodic, as if choral performance excluded the possibility of monodic performance or the other way around. It would all depend on which one of Sappho’s songs we happened to be reading. Without a diachronic point of view, we could be tempted to assume that any given song of Sappho must have been only choral or only monodic.

E. The personality of Sappho shows that she is a woman who loves girls. To say it this way is to engage in an overly narrow typing of Sappho as represented by the words of her songs. The songs of Sappho, as we will see, reveal a wide variety of female personae. Sappho can be a middle-aged woman or even an old woman, but she can also be a young girl. She can be a woman who loves girls, or a girl who loves another girl or is loved by other girls or by women. She can behave in a wide variety of ways, ranging from the stateliness exemplified by a priestess of the goddess Hera (Essay 4 at §35) all the way to frivolities evoking visions of a courtesan who enchants men listening to her songs sung at their drinking parties (Essay 21). She can also be a loving or a scolding sister (again, Essay 4). She can even show her love of boys, as we will see when we read Sappho’s poetic declaration of an erotic desire for radiant young male heroes like Phaon (Essay 8 and beyond).

0§11. Having outlined here, in ABCDE, some diachronic perspectives on the songmaking of Sappho, I will now need to find the most basic possible point of departure for tracing the evolution of this songmaking in light of my central argument, noted at point “C” in the Introduction at 0§10 above, that the occasions for each of the songs attributed to Sappho were determined by the historical circumstances that shaped the traditions of actually performing the songs. My plan, in what follows, is to start by focusing on one particular kind of occasion for performance—an occasion that I will initially describe simply as the celebration of a festival. And I already ask myself this hypothetical question: what would it be like, to hear—and see—a song of Sappho being performed at a festival in a given time and place? For answers, I will need to find evidence for the existence of such a festival, celebrated in Lesbos.

0§12. Such a festival did in fact exist. It was called the Kallisteia, and the name of this festival can be translated, roughly, as ‘Pageant of Beauty’. I summarize here some relevant details originally presented in N 2007|2009, rewritten as Essay 2 in the book Sappho 0. Those details are numbered here as ##1 2 3 4 (corresponding to §§4 5 6 7 in Essay 2 of Sappho 0):

#1. In the words of Alcaeus, preserved in a papyrus fragment (F 130b.13), there was in Lesbos a federal space called the temenos theōn ‘sacred precinct of the gods’, which was the designated place for celebrating a festival described as the occasion for recurring assemblies or ‘comings together’ of the people of Lesbos (F 130b.15, sunodoisi; N 1993:22). This festival, as we will see later (Essay 4§25 and following), was seasonally recurrent, celebrated at a place called Messon, which means, appropriately, ‘middle ground’, situated at the very center of the island of Lesbos. In the words of Alcaeus, this festival featured as its main spectacle the choral singing and dancing of Lesbiades ‘women of Lesbos’, described as ‘judged for their beauty’ (130b.17, krinnomenai phuān).

#2. The reality of such a seasonally recurring festival in Lesbos featuring the choral performances of women—or, to say it more broadly, women and girls—is independently verified by a scholion—that is, a learned note—written in a manuscript of the Homeric Iliad (scholion for 9.130), and from this note we learn that the name of this festival, as already mentioned, was the Kallisteia or ‘Pageant of Beauty’. In the relevant passage of the Iliad (9.130) as well as elsewhere in that epic, we find mythologized references to the women of Lesbos, described as exceptional in their beauty, who were captured by Achilles in the years that preceded the final destruction of Troy (Iliad 9.128–131, 270–273). These references in the Iliad can be analyzed as indirect references to the festival of the Kallisteia in Lesbos (further details in HPC=2010|2009:236, 242 = II§§289–290, 302).

#3. Another reference to the Kallisteia is attested in a poem from the Greek Anthology (9.189), where we read that this festival is celebrated within the temenos ‘sacred precinct’ of the goddess Hera, and that the celebrations involve choral singing and dancing by the women of Lesbos, with Sappho herself pictured as the leader of their khoros ‘chorus’ (Page 1955:168n4). Sappho in her songs is conventionally pictured as the lead singer of a chorus composed of the women of Lesbos, and she speaks as their main choral personality (PH=1990a:370 [12§60]).

#4. As we see from the wording of this poem in the Greek Anthology, Sappho’s songs are pictured as taking place within this sacred place. And such a place is marked by the deictic word tuide ‘here’, as for example in Sappho’s Song 17 (line 7). The whole song is quoted and translated in Sappho 0 4§50. Also, in Song 96 of Sappho, this same federal space of the people of Lesbos is once again marked by the deictic word tuide ‘here’ (line 2) as the sacred place of choral performance, and the noun molpā (line 5) makes it explicit that the performance takes the form of choral singing and dancing. In archaic poetry, the verb for ‘sing and dance in a chorus’ is melpesthai (PH=1990a:350–351 [12§29n62 and n64]).

0§13. One common feature of most ancient Greek festivals was that they were seasonally recurrent (extensive documentation in Nilsson 1906). And the festival of the Kallisteia in Lesbos was no exception, as we have already seen from the wording of Alcaeus in referring to this festival. In the very first essay of this volume, I will argue that there is a poetics of recurrence built into the songmaking of Sappho, and the wording that refers to such recurrence is most evident in the very first Song in the received textual tradition of Sappho’s songs.

Essay 1: Once again this time, Song 1 of Sappho

rewritten from N 2015.11.05

1§0. The seasonal recurrence of the festival of the Kallisteia in Lesbos is ostentatiously signaled, I argue, in Song 1 of Sappho. The wording that actually refers to such recurrence, I further argue, is the expression dēute (δηὖτε), which I translate this way: ‘once again, this time’.

1§1. This expression dēute ‘once again, this time’, which occurs at lines 15 and 16 and 18 in Song 1, refers not only to some episodically recurrent emotion of love as experienced by the speaker but also to the seasonally recurrent performance of the song on the festive occasion of the Kallisteia—a festival that I reconstruct all the way back to the earliest attested phases of the song’s evolution. About my translating this expression dēute specifically as ‘once again this time’, I cannot resist noting here, for the first but also the last and only time in this book, the delight I recurrently feel whenever I read Jonathan Culler, in his interpretation of Sappho’s Song 1, where he cites this translation of mine.[1]

1§2. I now show the Greek text of Song 1, followed by my working translation of the whole text, where I have highlighted the three occurrences of dēute (δηὖτε) ‘once again this time’:

|1 ποικιλόθρον’ ἀθανάτ’Αφρόδιτα, |2 παῖ Δίοc δολόπλοκε, λίϲϲομαί ϲε, |3 μή μ’ ἄϲαιϲι μηδ’ ὀνίαιϲι δάμνα, |4 πότνια, θῦμον,

|5 ἀλλὰ τυίδ’ ἔλθ’, αἴ ποτα κἀτέρωτα |6 τὰc ἔμαc αὔδαc ἀίοιϲα πήλοι |7 ἔκλυεc, πάτροc δὲ δόμον λίποιϲα |8 χρύϲιον ἦλθεc

|9 ἄρμ’ ὐπαϲδεύξαιϲα· κάλοι δέ ϲ’ ἆγον |10 ὤκεεc ϲτροῦθοι περὶ γᾶc μελαίναc |11 πύκνα δίννεντεc πτέρ’ ἀπ’ ὠράνωἴθε|12ροc διὰ μέϲϲω·

|13 αἶψα δ’ ἐξίκοντο· ϲὺ δ’, ὦ μάκαιρα, |14 μειδιαίϲαιϲ’ ἀθανάτωι προϲώπωι |15 ἤρε’ ὄττι δηὖτε πέπονθα κὤττι |16 δηὖτε κάλημμι

|17 κὤττι μοι μάλιϲτα θέλω γένεϲθαι |18 μαινόλαι θύμωι· τίνα δηὖτε πείθω |19 βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα [philotēs];[2] τίc ϲ’, ὦ |20 Ψάπφ’, ἀδικήει;

|21 καὶ γὰρ αἰ φεύγει, ταχέωc διώξει, |22 αἰ δὲ δῶρα μὴ δέκετ’, ἀλλὰ δώϲει, |23 αἰ δὲ μὴ φίλει [phileîn], ταχέωc φιλήϲει [phileîn] |24 κωὐκ ἐθέλοιϲα.

|25 ἔλθε μοι καὶ νῦν, χαλέπαν δὲ λῦϲον |26 ἐκ μερίμναν, ὄϲϲα δέ μοι τέλεϲϲαι |27 θῦμοc ἰμέρρει, τέλεϲον, ϲὺ δ’ αὔτα |28 ϲύμμαχοc ἔϲϲο.

Song 1 of Sappho = Prayer to Aphrodite[3]

stanza 1||1 You with pattern-woven flowers, immortal Aphrodite, |2 child of Zeus, weaver of wiles, I implore you, |3 do not dominate with hurts and pains, |4 Mistress, my heart!

stanza 2||5 But come here [tuide], if ever at any other time |6 hearing my voice from afar, |7you heeded me, and leaving the palace of your father, |8 golden, you came,

stanza 3||9 having harnessed the chariot; and you were carried along by beautiful |10 swift sparrows over the dark earth |11 swirling with their dense plumage from the sky through the |12 midst of the aether,

stanza 4||13 and straightaway they arrived. But you, O holy one, |14 smiling with your immortal looks, |15 kept asking what is it once again this time [dēute] that has happened to me and for what reason |16 once again this time [dēute] do I invoke you,

stanza 5||17 and what is it that I want more than anything to happen |18 to my frenzied [mainolās] heart [thūmos]? “Whom am I once again this time [dēute] to persuade, |19 setting out to bring [agein] her to your love [philotēs]? Who is doing you, |20 Sappho, wrong?

stanza 6||21 For if she is fleeing now, soon [takheōs] she will be pursuing. |22 If she is not taking gifts, she will be giving them. |23 If she does not love [phileîn], soon [takheōs] she will love [phileîn] |24 even against her will.”

stanza 7||25 Come to me even now, and free me from harsh |26 anxieties, and however many things |27 my heart [thūmos] yearns to get done, you do for me. You |28 become my ally in war.

1§3. As I proceed to elaborate on my interpretation of dēute (δηὖτε) ‘once again this time’ at lines 15 and 16 and 18 here, I begin by examining the context of line 18, where we see a shift from the persona of Sappho as the first-person speaker to the persona of Aphrodite herself, who now takes over as the first-person speaker. This shift is correlated with a shift from the persona of Aphrodite as the second-person addressee to the persona of Sappho, addressed by Aphrodite as Psapphă at line 20. Here is how I interpret this correlation:

In the part of Song 1 that we see enclosed within quotation marks in the visual formatting of modern editions (lines 18–24), the first-person ‘I’ of Sappho is now replaced by Aphrodite herself, who has been a second-person ‘you’ up to this point. We see here an exchange of roles between the first-person ‘I’ and the second-person ‘you’. The first-person ‘I’ now becomes Aphrodite, who proceeds to speak in the performing voice of Sappho to Sappho herself, who has now become the second-person ‘you’. During Aphrodite’s epiphany inside the sacred space of the people of Lesbos, a fusion of identities takes place between the goddess and the prima donna who leads the choral performance tuide, ‘here’ (line 5), that is, in this sacred space.[4]

1§4. I add here a detail, with reference to line 20: I interpret the underlying vocative form for the name of Sappho here, Ψάπφ’, as Psapphă, to be contrasted with the nominative form Psapphō. In terms of this interpretation, the short final vowel of Psapphă is then elided into the initial vowel of the next word (similarly in the case of Ψάπφ’ at line 5 of Song 94). The morphological variation that I posit here, Psapphă / Psapphō, corresponds to the morphological variation we see in the hypocoristic terms of affection apphă / apphō (ἄπφα / ἀπφώ), meaning something like ‘dear little girl’—and referring to a sister or some other girl or woman who is being addressed in a demonstratively loving way.[5]

1§5. That said, I now proceed to analyze further the affectionate exchange that is taking place between the persona of Aphrodite and the persona of Sappho in the context of praying a prayer. Why the prayer? It is because the persona of Sappho is suffering from the torment of unrequited love: some unnamed girl refuses to love her. But what is it that Aphrodite should do about this torment? The answer depends on the wording that we read at lines 18–19: τίνα δηὖτε πείθω |19 βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα; ‘Whom am I once again this time [dēute] to persuade, |19 setting out to bring [agein] her to your love?’. The restored form βαῖϲ᾿ ‘going’ at line 19 can be credited to Maryline G. Parca,[6] and I agree with the restoration.[7] The idiom that we see here involves the combining of bainō / bainein ‘go’ as a primary verb with the infinitive of a secondary verb, which in this case is agēn (agein), meaning ‘bring’, and Parca finds a comparable idiom in Homeric usage, citing this example:

βῆ δ’ ἰέναι ‘he set out to go’ (Iliad 4.199)

1§6. This idiom, which occurs frequently in both the Iliad and Odyssey—there are almost forty attestations—is the only Homeric example cited by Parca. But there are other examples, and I show two of them here:

βῆ δὲ θέειν ‘he went and ran’ (Iliad 2.183; 11.617, 805; 12.352; 14.354; 17.119, 698; 18.416; Odyssey 14.501; 22.19)

βῆ δ’ ἐλάαν ‘he went and drove off [in his chariot]’ (Iliad 13.27)

1§7. In these two Homeric examples, I have chosen to translate the idiom in informal English. Instead of saying ‘he set out to run’ and ‘he set out to drive off’, I have chosen more colloquial expressions that correspond more closely to the meaning of the first part of the idiom: ‘he went and ran’ and ‘he went and drove off’. But what about the first Homeric example, the one that was cited by Parca? In this case, βῆ δ’ ἰέναι, the colloquialism that I used to translate the second and the third examples won’t work. It would be a pleonasm to say in English ‘he went and went off’, matching ‘he went and ran’ or ‘he went and drove off’. That is why I resorted to the wording ‘he set out and went off’. Even in this case, though, colloquial English gives us a useful equivalent: ‘he up and went off’, which could be matched by saying ‘he up and ran’ or ‘he up and drove off’.

1§8. Now that I have compared the three Homeric examples I have cited, I am ready to interpret βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα at line 19 in Song 1 of Sappho. The prayer spoken by the persona of Sappho here, as understood by Aphrodite, expresses a wish that the goddess should set out and bring the girl, or, to say it more colloquially, Aphrodite should go and bring the girl. And now let me say it even more colloquially: the goddess should go out and get her. Sappho is too shy to go out and get the girl. She wants Aphrodite to do it for her. In saying it this way, I am thinking of the line in “Hey Jude”…

Hey Jude, don’t be afraid | You were made to go out and get her | The minute you let her under your skin | Then you begin to make it better.

“Hey Jude,” composed by Paul McCartney and performed by The Beatles; recorded 1968, side B: “Revolution”

1§9. In Song 1 of Sappho, to repeat, it is not the persona of Sappho who goes out and gets the girl: rather, she wants Aphrodite to do it for her, and the wording of Aphrodite at lines 13–24 shows that she understands what Sappho wants. Similarly in Iliad 3.399–412, the persona of Helen says reproachfully to Aphrodite that the goddess has a nasty habit of ‘bringing’ her, as a love-object, to her multiple lovers, and the Greek word that is used here for the ‘bringing’ of Helen by Aphrodite is agein (401: ἄξειc)—which is the same word used in Song 1 of Sappho with reference to the wish of Sappho—a wish well understood by Aphrodite—that the goddess should be ‘bringing’ (1.19: ἄγην) the unnamed girl, as a love-object, to Sappho.

1§10. As I said before, I agree with the reading and the interpretation of Parca for lines 18–19 of Song 1 of Sappho: τίνα δηὖτε πείθω |19 βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα; ‘Whom am I once again this time [dēute] to persuade, |19 setting out to bring [agein] her to your love [philotēs]?’ But I disagree with her view that the adverb dēute (δηὖτε) ‘once again this time’ at line 18 (and, by extension, at lines 15 and 16) is some kind of textual reference to the Homeric exchange between Aphrodite and Helen in Iliad 3.[8] In my view, the poetic language of Sappho does not cross-refer to the text of the Homeric Iliad as we know it: as I argued in the Introduction (above, point “A” at 0§10), the poetic language of Sappho is cognate with but not dependent on the poetic language of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey.

1§11. Distancing myself from the argument that the wording of Sappho’s Song 1 at lines 18–19 is based on “Homeric allusion,” I agree with the position of J.C.B. Petropoulos, who argues instead that this wording, including the insistent dēute (δηὖτε) ‘once again this time’ at line 18 (and, by extension, at lines 15 and 16), is related to the kind of wording we find in the language of love spells.[9] As Petropoulos shows, Sappho’s prayer in Song 1 is asking Aphrodite to go and bring an unnamed girl to Sappho by persuading this girl: τίνα δηὖτε πείθω |19 βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα; ‘Whom am I once again this time [dēute] to persuade [peithein], |19 setting out to bring [agein] her to your love [philotēs]?’ But what will it take to ‘persuade’ the girl, peithein, and thus ‘bring’ her, agein, to Sappho? In the traditional language of love spells, as we will now see, the actual ‘bringing’ of the beloved to the lover can readily modulate from ‘persuasion’ into compulsion.

1§12. In love spells, as Petropoulos shows, the lover who suffers from unrequited love can pray to the powers of the higher—or lower—world to compel the unresponsive beloved to start loving in return.[10] The act of compelling the unwilling beloved to become a willing lover can be seen as physical, not just mental and emotional. A striking example comes from a papyrus found at Hawara and dating from around the second century CE. In this text, a woman named Hērais is casting a spell on an unresponsive female beloved named Sarapias:

ἐξορκείζ[ω] cε Εὐάγγελε | κατὰ τοῦ ᾿Ανούβι[δο]c καὶ | τοῦ ῾Ερμοῦ καὶ [τ]ῶν λοι[πῶν] πάν|των κάτω, ἄξαι καὶ καταδ|ῆcαι Cαραπιάδα ἣν ἔτε|κεν ῾Ελένη ἐπ’ αὐτὴν ῾Ηρα|είδαν ἣν ἔτεκεν Θερμο|υθαριν, ἄρτι ἄρτι, τα|χὺ ταχύ. ἐξ ψυχῆc καὶ καρδίαc | ἄγε αὐτὴν τὴν Cαραπιά|δα . . .

Papyri Graecae Magicae (see PGM in the Bibliography) II 32.1–11

I adjure you, Euangelos, by Anubis and Hermes and by all the rest of you down below, bring [agein] and bind Sarapias whose mother is Helenē, [bringing Sarapias] to this Hērais here whose mother is Thermoutharin, now, now, quick [takhu], quick [takhu]. By way of her soul [psūkhē] and her heart [kardiā], bring [agein] this Sarapias herself [to me] . . .

1§13. I highlight the sense of urgency in the desire that is being expressed in the wording of this love spell. The ritualized haste that we see at work here in the insistent repetition ἄρτι ἄρτι, ταχὺ ταχύ ‘now, now, quick, quick’ is comparable to the wording of Aphrodite as she responds to the prayer of Sappho about the unresponsive girl: καὶ γὰρ αἰ φεύγει, ταχέωc διώξει, |22 αἰ δὲ δῶρα μὴ δέκετ’, ἀλλὰ δώϲει, |23 αἰ δὲ μὴ φίλει, ταχέωc φιλήϲει |24 κωὐκ ἐθέλοιϲα ‘For if she [= the girl] is fleeing now, soon [quickly: takheōs] she will be pursuing. |22 If she is not taking gifts, she will be giving them. |23 If she does not love [phileîn], soon [quickly: takheōs] she will love [phileîn] |24 even against her will’. As in love spells, the wording of Sappho’s prayer is meant to compel the unresponsive and unwilling beloved to turn around and love back, all too willingly.[11]

1§14. In this love spell, the act of agein ‘bringing’ the beloved to the lover is more a matter of physical compulsion and less a matter of verbal persuasion by way of sweet talk. And the compulsion can get even more intense. In the texts of other love spells, we see that the lover who suffers from unrequited love can pray to the powers of the netherworld to compel the unresponsive beloved to suffer in the same way—that is, to suffer the same physical symptoms of unrequited love as suffered by the compulsive lover.[12] The compulsion can be made visible by the symptoms of the torment caused by the experience of falling in love. For an example, Petropoulos cites the text of a love spell inscribed on a lead tablet from Hermoupolis Magna, dating from the third or fourth century CE. In this text, Supplementum Magicum I 42 (ed. Daniel and Maltomini, as cited in my Bibliography), a woman named Sophia who loves another woman named Gorgonia adjures a nekuodaimōn or ‘demon of corpses’ (line 12) to bring the unresponsive Gorgonia to a balaneion ‘bath-house’ (line 14), where the demon will then change into a balanissa ‘female bath-house attendant’ (again, line 14) who will now heat up the bath-water for Gorgonia. In this steamy situation, the torment of falling in love can begin:

καῦcον ποίρω|cον φλέξον τὴν ψυχὴν, τὴν καρδίαν, τὸ ἧπαρ, τὸ πνεῦμα ἐπ’ ἔρωτι Cοφία<c> ἣν αἴτεγεν ᾿Ιcάρα. ἄξατε | Γοργονία<ν> ἣν αἴτεγεν Νιλογενία, ἄξατε αὐτὴν, βαcανίcατε αὐτῆc τὸ cῶμα νυκτὸc καὶ ἡμαίραc, δαμάcα|ται αὐτὴν ἐκπηδῆcη ἐκ παντὸc τόπου καὶ πάcηc οἰκίαc φιλοῦcα<ν> Cοφία<ν>

Supplementum Magicum I 42.14–17 (ed. Daniel and Maltomini)

Burn and set on fire her soul [psūkhē], her heart [kardiā], her liver, and her breath with love [erōs]for Sophia whose mother is Isara. [All] you [powers] must bring [agein] Gorgonia, whose mother is Nilogeneia, [to me]. You must bring [agein] her [to me], tormenting her body night and day. Compel her to bolt from wherever she is, from whatever household, as she feels the love for Sophia.

1§15. Reading such attestations of agein ‘bring’ in these love spells, we can see clearly the specialized use of this word in expressing sexual attraction. I suggest that we can see a comparable use of agein ‘bring’ in the expression βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην ἐc ϲὰν φιλότατα ‘setting out to bring [agein] her to your love [philotēs]’ at line 19 of Song 1, where Aphrodite’s wording refers to the action of attracting most urgently the unresponsive beloved. But the urgency of sexual attraction that we see expressed in the songmaking of Sappho is more subtle, as Petropoulos observes in making this wry comment: “What Aphrodite tactfully omits, it seems, is the provision that Sappho’s new favo[u]rite will suffer the impediments of bodily and psychological functions and activities conventionally associated with love spells.”[13]

1§16. Petropoulos concludes his comparison of love spells with Song 1 of Sappho by observing: “Once the girl falls in love and comes to Sappho, the poetess will be only too glad to accept her philotēs [love].”[14]

1§17. But there is an alternative interpretation of Sappho’s prayer to Aphrodite, as formulated by Anne Carson. She thinks that Sappho is asking Aphrodite to make sure that the unnamed girl who is being pursued, once she is a woman, will suffer the same torment of unrequited love that Sappho is now suffering: the next time around, it will be this new woman who will be rejected by some new girl emerging from the next generation of girls—and deservedly so, because such is the “justice” of Aphrodite.[15] A variation on this kind of interpretation is offered by Benjamin Bennett: in terms of his argument, the unrequited love that will be suffered by the new woman is better understood as the “revenge” of Aphrodite—or, we may say, the “revenge” of Sappho.[16]

1§18. So, how am I to choose between two such interpretations? From a diachronic point of view, as I outlined it in the Introduction, I would argue that I really do not have to choose. Here is what I mean. The persona of Sappho may be praying to Aphrodite to go and bring to her the girl who has so far rejected her love, but this girl may in the future become a woman who prays the same prayer. Now it will be this future woman’s turn to be praying to Aphrodite to go and bring to her the girl, but, this time around, that girl will be a new girl—and, this time around, the future woman will be the new Sappho. Each successive ‘dear little girl’ pursued by Sappho will become a new Sappho in her own turn. And here once again (going back to 1§4 above) I recall the meaning of the name of Sappho, ‘dear little girl’. So, each successive Sappho was once upon a time a ‘dear little girl’ in her own right.

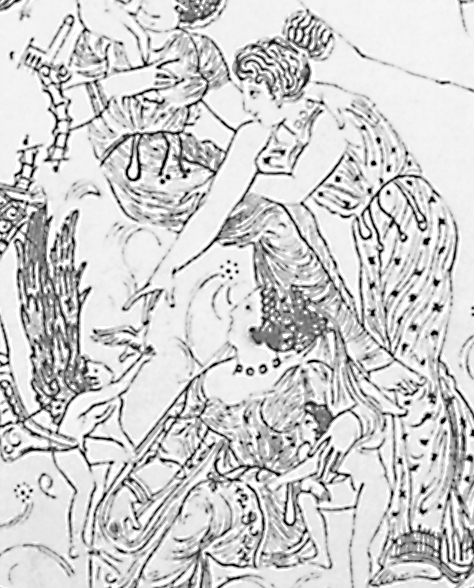

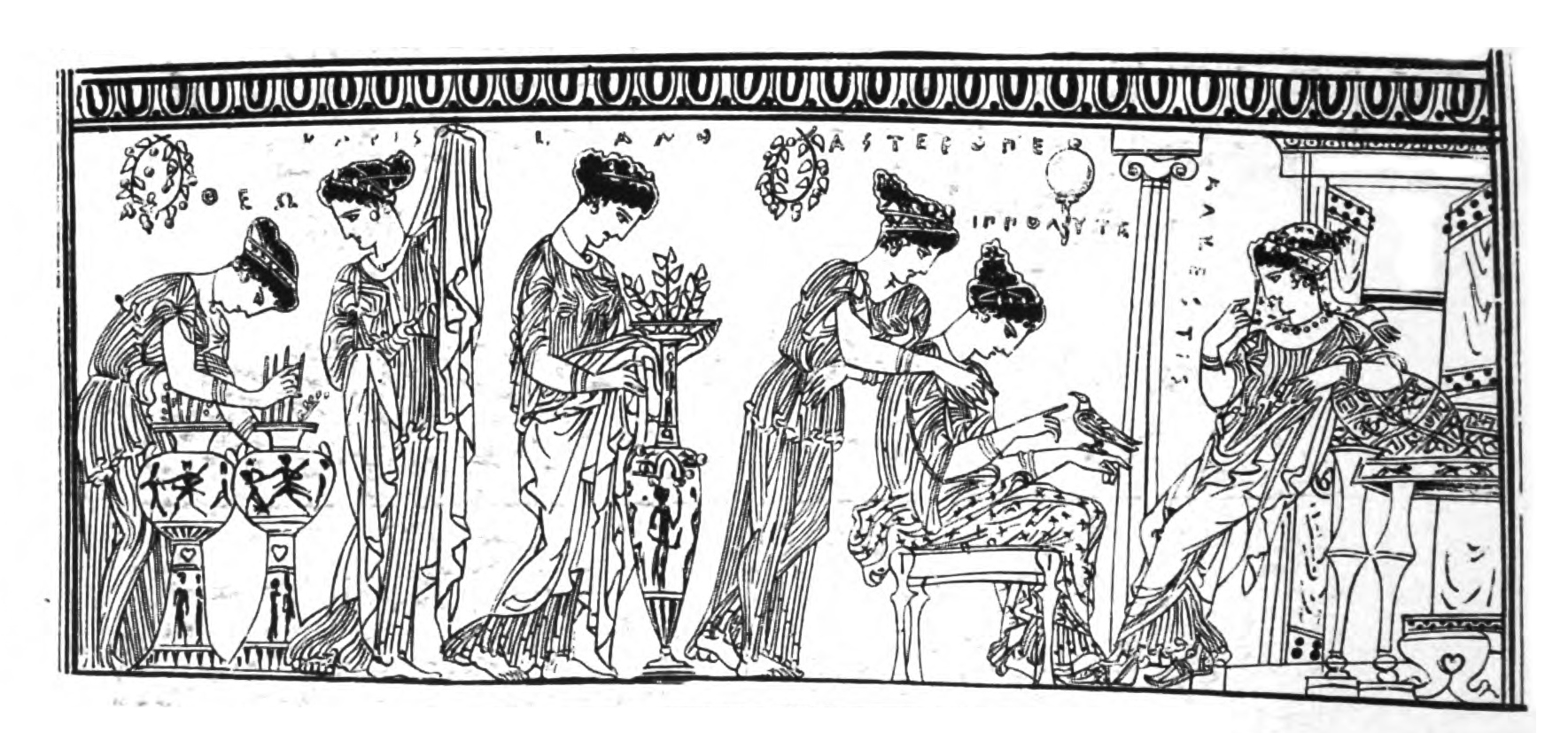

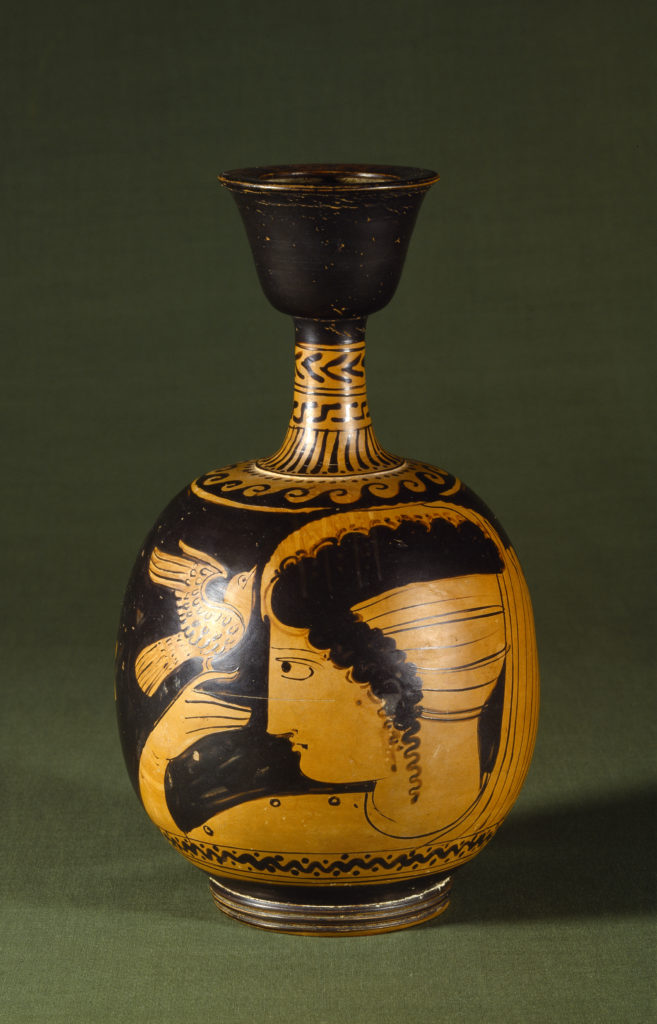

1§19. Support for this diachronic interpretation can be found in the visual arts of Athens in the fifth century. I have in mind an image of Sappho that is painted on a red-figure kalyx-krater dated to the first third of the fifth century BCE and attributed to the Tithonos Painter (Bochum, Ruhr-Universität Kunstsammlungen, inv. S 508).[17] On the obverse side of this vase, we see the image of a woman in a dancing pose.[18] She is wearing a cloak or himation over her khitōn, and a snood (net-cap) or sakkos is holding up her hair. As she “walks,” she carries an orientalizing string instrument called the barbiton in her left hand (more on this instrument at 2§15 below). Meanwhile, her gracefully extended right hand is holding a plectrum (Greek plēktron). The inscribed lettering placed not far from her mouth indicates that she is Sappho (CΑΦΦΟ).

1§20. This picture of Sappho on the obverse side of this vase painted by the Tithonos painter must be contrasted with the picture on the reverse side, as Dimitrios Yatromanolakis has shown.[19] He argues that the obverse and the reverse must be viewed together, seeing a symmetry in the depiction of Sappho on the obverse and the depiction of another female figure dressed similarly on the reverse: she too, like Sappho, is wearing a cloak or himation over her khitōn, and a snood or sakkos is holding up her hair.

1§21. The correlation of the pictures painted on the two sides of this vase is analyzed further by Yatromanolakis, and I offer here an epitome:

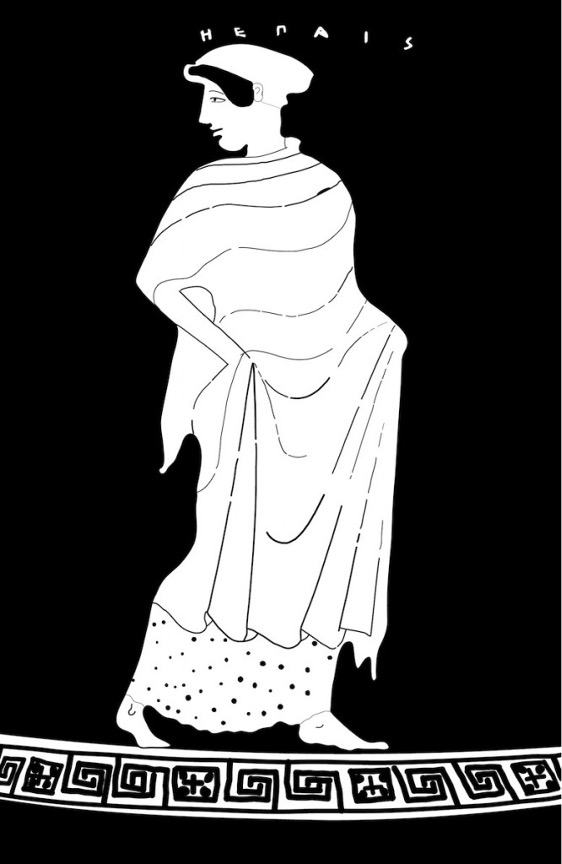

The symmetry is clarified as soon as we realize that there is a second, hitherto unknown, inscription on the reverse of this vase. Near the sakkos holding up the hair of this female figure paired with Sappho is lettering that reads ΗΕ ΠΑΙC (= hē pais), meaning ‘the girl’. If the viewer’s eye keeps rotating the vase, the two female figures eternally follow each other, but because their position is symmetrically pictured, they can never gaze at each other. Nor can a viewer ever gaze at both figures at the same time—at least, without a mirror.[20]

1§22. So, the pais ‘girl’ is eternally pursued by the singing and dancing Sappho as painted by the Tithonos painter. But Sappho is in turn eternally pursued by the girl. The girl of the present time will become the woman of a future time who will pursue a girl of that future time just as she herself had once been pursued in time past. As we hear in Song 1 of Sappho, line 21, καὶ γὰρ αἰ φεύγει, ταχέωc διώξει ‘for if she is fleeing now, soon [takheōs] she will be pursuing’.

1§23. Still, I think that the moment of catching up is eternally deferred. The woman cannot catch up with the girl she once had been, and the girl cannot catch up with the woman she will become. This is not just amor versus, it is amor conversus. It is a yearning for a merger of identities as woman pursues girl pursues woman. Such a merger could conceivably happen, but only in the mentality of myth fused with ritual. I have studied this mentality elsewhere, comparing it to the concept of the “Changing Woman” in the female initiation rituals and songs of the Navajo and Apache peoples:[21] as we learn from interviews with women who experience such rituals, Changing Woman defies old age even as she grows old, since “she is always able to recapture her youth.”[22]

1§24. I come to the end of this essay without being able to come to a full stop. A diachronic Sappho will need further contemplation, and I will have to come back to this subject not just once again as I go ahead with my argumentation.

Notes

[1] Culler 2015:356n1, with reference to my translation in PP=1996a:100. In an article about dēute (δηὖτε) by Sarah Mace (1993), she points to an idea I expressed in an earlier work of mine: that the specific attestations of this word at lines 15 and 16 and 18 in Song 1 of Sappho should be compared with all other attestations in ancient Greek lyric poetry (Mace 1993:337n8 with reference to N 1973:142n18). While surveying these attestations in the same article, she goes on to say that I do not “pursue the idea to any distinct conclusions” (Mace p. 338n11). I object. Instead, I would say that my conclusions about this word, as outlined in my essay here (and as already noted in N 1973:142n18), are distinct from hers.

[2] In what follows, I will comment on the restored reading βαῖϲ᾿ ἄγην at line 19.

[3] H24H Hour 5 Text F.

[4] H24H 5§50, with reference to a more detailed analysis in N 1996a:97–103.

[5] I elaborate on this point in Essay 4§§4–5 below.

[6] Parca 1982:47–48.

[7] PP=1996a:98n34

[8] Parca 1982:60, relying on the argumentation of Rissman 1980.

[9] Petropoulos 1993. At p. 51n51, he specifically argues against the idea that the wording in Sappho 1.18–19 is a matter of “Homeric allusion,” as argued by Parca 1982:49–50. See also Petropoulos p. 44n5.

[10] Petropoulos 1993:45–53. For more on the theme of “compulsory persuasiveness,” see Petropoulos p. 48.

[11] For further examples of ritualized haste in love spells, see Petropoulos 1993:47.

[12] Petropoulos 1993:45–53.

[13] Petropoulos 1993:52.

[14] Petropoulos 1993:52.

[15] Carson 1980.

[16] Bennett 2014:14–18.

[17] In what follows, I present a compressed version of what I argue in Essay 3 of Sappho 0.

[18] I have more to say in Essay 3 of Sappho 0 about the stylized dance implied by such a “walking style” in fifth-century Athenian paintings.

[19] Yatromanolakis 2005; also 2007: 88–110, 248, 262–279.

[20] Essay 3 of Sappho 0, following Yatromanolakis 2005, who was the first to read and publish this inscription.

[21] PP=1996a:101–103.

[22] Basso 1966:151.

Essay 2: Sappho’s Tithonos

rewritten from N 2009|2010

2§0. Essay 2 here, which is rewritten from an essay about the “New Sappho” that was originally printed as Nagy 2009/2010 (the page-breaks in the printed version of that text will be tracked here), had been rewritten once before, in Classical Inquiries (Nagy 2015.11.12) and that rewriting is now superseded by a newly rewritten version that I present here. We pick up from where I left off in Essay 1 of Sappho I, where I have highlighted the idea of a cycle from girl to woman back to girl in the poetics of Sappho—and where I noted the use of the word pais in the sense of ‘girl’ as inscribed in a vase painting that showed the pursuit of a girl by a woman who was in turn pursued by the girl in a seemingly eternal cycle. I see a comparable use of the word pais in line 1 of a song of Sappho about Tithonos. This song has been reconstructed by way of joining previously unjoined fragments of papyrus, and the song that emerged from the reconstruction came to be known as the “New Sappho” (as in a book about this song, edited by Greene and Skinner, 2009/2010), though now we must reckon with an even newer set of discoveries involving papyri that contain fragments of other songs of Sappho that are nowadays called the “Newest Sappho” (as in a book about these songs, edited by Bierl and Lardinois, 2016). With these qualifications duly noted, I will hereafter refer to the song of Sappho about Tithonos simply as Sappho’s Tithonos.

2§1. There are two versions of Sappho’s Tithonos, attested in two distinct sets of papyrus fragments. I start here by quoting the first of the two versions of this song (based on an initial publication by Dirk Obbink in 2010), followed by my own working translation:

|1 [. . . words missing . . . ἰ]ο̣κ[ό]λ̣πων κάλα δῶρα, παῖδεϲ, |2 [. . . words missing . . .τὰ]ν̣ φιλάοιδον λιγύραν χελύνναν· |3 [. . . words missing . . .] π̣οτ̣’ [ἔ]ο̣ντα χρόα γῆραϲ ἤδη |4 [. . . words missing . . .]ἐγ]ένοντο τρίχεϲ ἐκ μελαίναν· |5 βάρυϲ δέ μ’ ὀ [θ]ῦμο̣ϲ̣ πεπόηται, γόνα δ’ [ο]ὐ φέροιϲι, |6 τὰ δή ποτα λαίψηρ’ ἔον ὄρχηϲθ’ ἴϲα νεβρίοιϲι. |7 τὰ ⟨μὲν⟩ ϲτεναχίϲδω θαμέωϲ· ἀλλὰ τί κεν ποείην; |8 ἀγήραον ἄνθρωπον ἔοντ’ οὐ δύνατον γένεϲθαι. |9 καὶ γάρ π̣[ο]τ̣α̣ Τίθωνον ἔφαντο βροδόπαχυν Αὔων |10 ἔρωι φ̣ ̣ ̣α̣θ̣ε̣ιϲαν βάμεν’ εἰϲ ἔϲχατα γᾶϲ φέροιϲα[ν], |11 ἔοντα̣ [κ]ά̣λ̣ο̣ν καὶ νέον, ἀλλ’ αὖτον ὔμωϲ ἔμαρψε |12 χρόνωι π̣ό̣λ̣ι̣ο̣ν̣ γῆραϲ, ἔχ̣[ο]ν̣τ̣’ ἀθανάταν ἄκοιτιν. |13 [. . . words missing . . .]ιμέναν νομίϲδει |14 [. . . words missing . . .]αιϲ ὀπάϲδοι |15 ⸤ἔγω δὲ φίλημ’ ἀβροϲύναν, . . .⸥ τοῦτο καί μοι |16 τὸ λά⸤μπρον ἔρωϲ ἀελίω καὶ τὸ κά⸥λον λέ⸤λ⸥ογχε.

Sappho’s Tithonos 1–16

(On the reading φίλημ’ not φίλημμ’, I agree with de Kreij 2016:68.)

|1 [. . .] gifts of [the Muses], whose contours are adorned with violets, [I tell you] girls [paides] |2 [. . .] the clear-sounding song-loving lyre. |3 [. . .] skin that was once tender is now [ravaged] by old age [gēras], |4 [. . .] hair that was once black has turned (gray). |5 The throbbing of my heart is heavy, and my knees cannot carry me |6 —(those knees) that were once so nimble for dancing like fawns. |7 I cry and cry about those things, over and over again. But what can I do? |8 To become ageless [a-gēra-os] for someone who is mortal is impossible to achieve. |9 Why, even Tithonos once upon a time, they said, was taken by the dawn-goddess [Eos], with her rosy arms |10 —she felt [. . .] passionate-love [eros] for him, and off she went, carrying him to the ends of the earth, |11 so beautiful [kalos] he was and young [neos], but, all the same, he was seized |12 in the fullness of time by gray old age [gēras], even though he shared the bed of an immortal female. |13 [. . .] |14 [. . .] |15 But I love [phileîn] luxuriance [(h)abrosunē] [. . .] this, |16 and passionate-love [erōs] for the Sun has won for me its radiance [tò lampron] and beauty [tò kalon].

2§2. Before proceeding, I need to note that there have been many improvements in editing this fragmentary text since its initial publication (2010); I prefer the updated edition published by Camillo Neri in 2021 (Sappho F 58a and F 58b). Also, I need to offer some basic background about the papyri that have led to the reconstruction of Sappho’s Song of Tithonos. The papyrus texts, varying in date, can be designated as Π¹ and Π². The first, Π¹, is a Cologne papyrus dated to the third century BCE (P.Köln inv. 21351 + 21376); the second, Π², is an Oxyrhynchus papyrus dated to the second or third century CE (P.Oxy. 1787). The papyrus Π¹ preserves those parts of the Tithonos Song that occupy the opening portions of the lines, while the papyrus Π² preserves the closing portions. The text that follows line 12 in Π¹ is another song, composed in non-Sapphic meter, and that text is not given in what I have just quoted above. The text that follows line 12 in Π² continues the same song, and it is this text that I give in lines 13–16 above. These lines Π² 13–16 are the equivalent of lines 23–26 in a text that used to be known simply as Fragment 58 of Sappho. At lines 15–16, the wordings enclosed in half-square brackets include restorations from an incomplete quotation by Athenaeus 15.687b (who in turn is citing Clearchus, F 41 ed. Wehrli). My translation of lines 15–16 above is based on the reading ἔρωϲ ἀελίω (PH=1990a:285 [10§18], GMP=1990b:261–262, PP=1996a:90, 102–103) instead of a commonly accepted emendation ἔροc τὠελίω. In terms of the first reading, ἔρωϲ ἀελίω, the Sun is the objective genitive of erōs, ‘passionate-love’. In terms of the second reading, ἔροc τὠελίω, the translation would be … ‘passionate-love [eros] has won for me the radiance and beauty of the Sun’. I agree with Neri (2021:676), who argues for the first reading and against the second reading.

2§3. Before I comment on the paides ‘girls’ who are addressed by the speaker at line 1 as I have quoted it above—the word paides here refers not to ‘boys’ but to ‘girls’— I first give further background about the overall composition of Sappho’s Tithonos.

2§4. This composition, Sappho’s Tithonos, belongs to a larger textual set that is sometimes called the “New Sappho”—where the “newness,” as I already noted, is due to the “new” text of a newly-found Cologne papyrus, already mentioned, which is dated to the third century BCE (P.Köln inv. 21351 + 21376). This “new” text, as we have seen, is distinct in both form and content from an already-known text of Sappho, found in an Oxyrhynchus papyrus, which is dated to the second or third century CE (P.Oxy. 1787). In the two papyri, Π¹ and Π², dated about a half a millennium apart, the songs of Sappho are evidently arranged in a different order. Both papyri contain fragments of three songs, but only the second of the three songs in each papyrus is the same. The other two songs in each papyrus are different from each other. The sameness of the second song in each papyrus is evident from an overlap between the wording of lines 9–20 in the earlier papyrus (Π1 in the initial edition of 2010, quoted above) and of lines 11–22 in the later papyrus (Π2). But even this same song, which is about Tithonos, is not really the same in the two papyri. The text of Sappho’s Tithonos in the later papyrus is longer, as we have already seen. After line 22, which corresponds to line 12 in the version of the earlier papyrus as I quoted it above, the song seems to keep going for another four lines, all the way through line 26, before a third song starts at the next line. By contrast, the text of Sappho’s Tithonos in the earlier papyrus is shorter: after line 12, there are no further lines for this song, and a third song starts at the next line. This difference between the two texts of Sappho’s Tithonos leads to a question: which of the texts is definitive—the shorter one or the longer one? In what follows, I will formulate an answer based on what we know about the reception of Sappho in the city-state of Athens during the fifth century BCE.

2§5. This reception, as I argue, was an aspect of the actual transmission of Sappho’s songs in performance—a continuous transmission that I trace all the way back to the foundational context of these songs as they had been performed at Lesbos—maybe as early as around 600 BCE. In other words, I am arguing that the reception of Sappho in Athens, many years later, was not some new revival of an old Aeolian lyric tradition that had been discontinued. This is not a story of Sappho interrupted and then revived. Instead, it is a story of Sappho continued—and thereby transformed. As an analogy for the reception of Sappho’s songmaking in Athens during the fifth century, I think of the reception of Homeric poetry in the same city during {176|177} the same period. This Athenian Homer was not some revival of an old Ionian epic tradition that had been discontinued: rather, the Homeric tradition in Athens during the Classical period of the fifth century BCE was an organic continuation of earlier Preclassical traditions stemming from Ionians inhabiting the Asiatic side of the Aegean Sea.[1]

2§6. An essential aspect of Sappho’s reception in Athens, I argue, was the tradition of performing her songs in a sympotic context, which differentiated these songs from what they once had been in their primarily choral context.[2] Before proceeding further, I pause for a moment to explain what I mean by sympotic and choral contexts.

2§7. When I speak of a choral context, I have in mind the general idea of performances by a khoros, conventionally translated as ‘chorus’. Already in the Introduction, §10D, I offered a working definition of the khoros: it is a group of performers who sing and also potentially dance a given song within a space (real or notional) that is sacred to a divinity or to a constellation of divinities.[3] In the case of songs attributed to Sappho, they were once performed by women or girls who were singing and dancing within such a sacred space.[4] And the divinity most closely identified with most of her songs was Aphrodite.[5]

2§8. When I speak of a sympotic context, I have in mind the general idea of performances at a sumposion or ‘symposium’—but also a related idea. Besides sympotic performances, we have to account also for comastic performances, that is, performances by a kōmos, which is a group linked with an occasion conventionally termed a ‘revel’. Pragmatically speaking, we can say that the kōmos is both the occasion of a ‘revel’ and the group engaged in that ‘revel’. I offer a working definition of the kōmos: it is a group of male performers who sing and also potentially dance a given song on a festive occasion that calls for the drinking of wine.[6]

2§9. Here I review the implications of this definition. The combination of wine and song expresses the ritual communion of those participating in the kōmos. This communion creates a bonding of the participants with one another and with the divinity who makes the communion sacred, that is, Dionysus.[7] To the extent that the kōmos is a group of male performers who sing and dance in a {177|178} space (real or notional) that is sacred to Dionysus, it can be considered a subcategory of the khoros.[8] The khoros is the general category, since it can be sacred not only to the god Dionysus but also to other divinities. Morever, the kōmos can be viewed as a subcategory because comastic performers are understood to be male whereas choral performers can be male or female.

2§10. The concept of the kōmos is linked with the concept of the symposium, and the primary link is the god Dionysus himself, since the drinking of wine, sacred to Dionysus, is linked with comastic as well as sympotic occasions. That is why I have found it convenient to use the term comastic interchangeably with the term sympotic in referring to contexts involving Dionysus. I should note, however, that the symposium, in all its attested varieties, could occasionally accommodate more innovative kinds of singing and dancing besides the kinds we find generally attested in cases involving the kōmos. In particular, as we will see later, various orientalizing contexts of symposia could be different in some ways from traditionally older contexts of the kōmos.[9] Moreover, as we will see in upcoming argumentation, attendance at a symposium, in all its varieties, was not necessarily limited to male participants, by contrast with the more conventional understanding of a kōmos. This is not to say that women of social standing could mingle freely with men at a symposium, but the fact remains, as we will see, that there did exist all-female events that can definitely be described as symposia. In any case, for now I concentrate on conventional concepts of the kōmos.

2§11. Back when Sappho is thought to have flourished in Lesbos, around 600 BCE, we expect that her songs would be performed by women in the context of the khoros. Around the same time in Lesbos, on the other hand, the songs of Alcaeus would be performed by men in the context of the kōmos. This context is signaled by the use of the verb kōmazein ‘sing and dance in the kōmos’, which is actually attested in a song of Alcaeus (F 374.1). On other occasions, however, the songs of Alcaeus could be performed, potentially, not by a kōmos but even by a male khoros, as for example his Hymn to the Divine Twins, the Dioskouroi (Alcaeus F 34).

2§12. There is an overlap, on the other hand, in performing the songs attributed to Sappho. I argue that such songs could be performed not only by women in a khoros but also by men in a kōmos.[10] To avoid any misunderstanding here, I should note that the kōmos involves forms of “high art” as well as “low art.” A prominent example of the higher forms is the epinician poetry of Pindar and Bacchylides, which is stylized as comastic performance. And, within the mythological framework of the stylized kōmoi of Pindar and Bacchylides, the male singers and dancers could be imagined at special moments as female singers and dancers who are performing in a chorus. A case in point is Song 13 of Bacchylides, which features a mythically performing khoros ‘chorus’ of nymphs embedded within a ritually performing kōmos of men.[11]

2§13. I trace this kind of embedded choral performance from Lesbos to Samos, where it became part of the court poetry of Anacreon. In the subsections of 2§13 that follow (§13.1–6), I epitomize the relevant arguments that are presented more fully in the book Sappho 0.[12]

§13.1. Anacreon was court poet to Polycrates of Samos, the powerful ruler of an expansive maritime empire in the Aegean world of the late sixth century. The lyric role of Sappho was appropriated by the imperial court poetry of Anacreon. {178|179}

§13.2. This appropriation can be viewed only retrospectively, however, through the lens of poetic traditions in Athens. That is because the center of imperial power over the Aegean Sea shifted from Samos to Athens when Polycrates the tyrant of Samos was captured and executed by agents of the Persian empire. Parallel to this transfer of imperial power was a transfer of musical prestige, politically engineered by Hipparkhos the son of Peisistratos and tyrant of Athens. Hipparkhos made the powerful symbolic gesture of sending a warship to Samos to fetch Anacreon and bring him to Athens (“Plato” Hipparkhos228c). This way, the Ionian lyric tradition as represented by Anacreon was relocated from its older imperial venue in Samos to a newer imperial venue in Athens. Likewise relocated was the Aeolian lyric tradition as represented by Sappho—and also by Alcaeus.

§13.3. The new Aegean empire that was taking shape under the hegemony of Athens became the setting for a new era in lyric poetry, starting in the late sixth century and extending through most of the fifth. In this era, Athens became a new stage, as it were, for the performing of Aeolian and Ionian lyric poetry as mediated by the likes of Anacreon. The most public context for such performance was the prestigious Athenian festival of the Panathenaia, where professional monodic singers performed competitively in spectacular restagings of lyric poetry. The Aeolian and Ionian lyric traditions exemplified by Anacreon figured prominently at this festival.

§13.4. This kind of poetry, despite the publicity it got from the Panathenaia as the greatest of the public festivals of Athens, could also be performed privately, that is, in sympotic contexts. Most telling are the references in Athenian Old Comedy to the sympotic singing of Aeolian and Ionian lyric. I cite an example from Aristophanes (F 235 ed. Kassel/Austin), where singing a song of Anacreon at a symposium is viewed as parallel to singing a song of Alcaeus: ᾆσον δή μοι σκόλιόν τι λαβὼν Ἀλκαίου κἈνακρέοντος ‘sing me some skolion, taking it from Alcaeus or Anacreon’.[13] {179|180} Elsewhere, in the Sympotic Questionsof Plutarch (711d), singing a song of Anacreon at a symposium is viewed as parallel to singing a song of Sappho herself: ὅτε καὶ Σαπφοῦς ἂν ᾀδομένης καὶ τῶν Ἀνακρέοντος ἐγώ μοι δοκῶ καταθέσθαι τὸ ποτήριον αἰδούμενος ‘whenever Sappho is being sung, and Anacreon, I think of putting down the drinking cup in awe’.

§13.5. In general, the Dionysiac medium of the symposium was most receptive to the Aeolian and Ionian lyric traditions exemplified by the likes of Anacreon, Alcaeus, and Sappho. There is an anecdote that bears witness to this reception: it is said that Solon of Athens became enraptured by a song of Sappho as sung by his own nephew at a symposium (Aelian via Stobaeus 3.29.58).[14]

§13.6. The correlation of Aeolian lyric with the Ionian lyric of Anacreon in these contexts is relevant to an explicit identification of Anacreon with the Dionysiac medium of the symposium. In a pointed reference, Anacreon is pictured in the lavish setting of a grand symposium hosted by his patron, the tyrant Polycrates, in the heyday of the Ionian maritime empire of Samos. The reference comes from Herodotus (3.121), who pictures Polycrates in the orientalizing pose of reclining on a sympotic couch in the company of his court poet Anacreon: καὶ τὸν Πολυκράτεα τυχεῖν κατακείμενον ἐν ἀνδρεῶνι, παρεῖναι δέ οἱ καὶ Ἀνακρέοντα τὸν Τήιον ‘and he [= a Persian agent] found Polycrates reclining in the men’s quarters, and with him was Anacreon of Teos’.[15]

2§14. The poet Anacreon, as a protégé of the tyrant Polycrates, would of course be featured as the celebrated performer of the poet’s own songs at such symposia, which in ordinary contexts would be private events. In the case of tyrants however, the distinction between singing in a symposium and singing in a concert, which would be a public event, could easily be blurred, since the political ambitions of a tyrant like Polycrates led to a mentality of claiming ownership of public events like concerts featuring the singing of songs, as if such events were the tyrant’s own private property—property that he would be willing to share with the public in his claimed role as a generous sponsor. In a standalone essay (N 2024.01.11) I have more to say about such an ideological merger of what is private and what is public in media controlled by tyrants, especially with reference to songs as publicly performed by Anacreon and sponsored by Polycrates as patron. For now, however, I will focus not on the songmaking done by Anacreon himself in Samos but on his appropriation, in that same context, of the earlier songmaking of Sappho and Alcaeus in the context of Lesbos. Such appropriation, I must emphasize, would still be part of Anacreon’s songmaking in the context of Samos, where he merged his own songs with the earlier songs of predecessors like Sappho and Alcaeus. Accordingly, I will hereafter refer to such merged songmaking more generally: such songs were not so much Anacreon’s songs, they were merely Anacreontic songs. And the point is, the performance traditions of Anacreontic songmaking in Samos lived on in Athens. Even the compatibility of Anacreontic songmaking with both private and public contexts of performance lived on in Athens, where the traditions of performing Anacreontic songs continued to be shaped and reshaped {180|181} in two different contexts—both the private context of symposia and the public context of grand concerts organized at the festival of the Panathenaia.

2§15. A symbol of the convergence of sympotic and Panathenaic traditions in performing the songs of Anacreon—and of Sappho and Alcaeus—was an exotic string instrument of Lydian origin known as the barbiton (a byform is barbitos), as we see from references in the visual as well as the verbal arts.[16] The morphology of this instrument made it ideal for a combination of song, instrumental accompaniment, and dance. With its elongated neck, the barbiton produced a low range of tone that best matched the register of the human voice, and its shape was “ideally suited to walking musicians, since it could be held against the left hip and strummed without interfering with a normal walking stride.”[17] What is described here as “a normal walking stride” could modulate into a dancing pose, as we see in pictures representing Anacreon himself in the act of singing and dancing while accompanying himself on the barbiton.[18]

2§16. The figure of Anacreon as a performer at the Panathenaia is parodied in the verbal as well as the visual arts. A case in point is Women at the Thesmophoria, a comedy by Aristophanes. Here the tragic poet Agathon is depicted as wearing a turban and a woman’s khitōn—costuming that matches the costume of the lyric poet Anacreon as depicted by the Kleophrades Painter (Copenhagen MN 13365).[19] In the comedy of Aristophanes, the stage Agathon even says explicitly that his self-staging is meant to replicate the monodic stagings of Ibycus, Anacreon, and Alcaeus (lines 159-163). This reference indicates that Agathon as a master of tragic poetry was strongly influenced by the tradition of performing lyric poetry monodically at the Panathenaia.[20]

2§17. Another source of influence was the tradition of performing lyric poetry in an ensemble like the kōmos. There is a potential for choral as well as monodic parody in Old Comedy.[21] {181|182}The case in point is again the Women at the Thesmophoria. In this comedy of Aristophanes, the Panathenaic persona of the tragic poet Agathon extends into a Dionysiac persona when the acting of the actor who plays Agathon shifts from dialogue to chorus. Once the shift takes place, there can be a choral as well as monodic self-staging of the stage Agathon.[22] And such choral stagings would most likely be comastic in inspiration.

2§18. Returning to the symbolic value of the barbiton, I next consider two conflicting myths about the invention of this string instrument. According to one myth, the inventor was Anacreon (Athenaeus 4.175e); according to the other, the inventor was an archetypal poet from Lesbos known as Terpander (Athenaeus 14.635d). I interpret the symbolic value of these myths as follows:[23]

Just as the figure of Anacreon was associated with the kitharā as well as the barbiton, so too was the older figure of Terpander. In fact, Terpander of Lesbos was thought to be the prototype of kitharōidoi ‘kitharā-singers’ (Aristotle F 545 ed. Rose; Hesychius under the entry μετὰ Λέσβιον ᾠδόν; Plutarch Laconic sayings 238c). Pictured as an itinerant professional singer, Terpander was reportedly the first of all winners at the Spartan festival of the Karneia (Hellanicus FGH 4 F 85 by way of Athenaeus 14.635e).[24] Tradition has it that the Feast of the Karneia was founded in the twenty-sixth Olympiad, that is, between 676 and 672 BCE (Athenaeus 14.635e-f).

Not only was Terpander of Lesbos thought to be the prototypical kitharōidos or ‘kitharā-singer’ (“Plutarch” On Music 1132d, 1133b-d). He was also overtly identified as the originator of kitharōidiā or ‘kitharā-singing’ as a performance tradition perpetuated by a historical figure named Phrynis of Lesbos; just like Terpander, Phrynis was known as a kitharōidos (“Plutarch” On Music 1133b). And the historicity of this Phrynis is independently verified: at the Panathenaia of 456 (or {182|183} possibly 446), he won first prize in the competition of kitharōidoi (scholia to Aristophanes Clouds 969). [25]

2§19. Given the interchangeability of barbiton and kitharā in traditions about Terpander as the prototypical kitharōidos ‘kitharā-singer’, I turn to the traditions about Anacreon as shown in Anacreontic vase paintings: here too we find an interchangeability of barbiton and kitharā. In both cases of interchangeability, it is implied that the kitharā is the more traditional of these two kinds of instrument, since the barbiton is figured as something invented by the Asiatic Ionian Anacreon according to one version (Athenaeus 4.175e) or by the Asiatic Aeolian Terpander according to another (Athenaeus 14.635d).

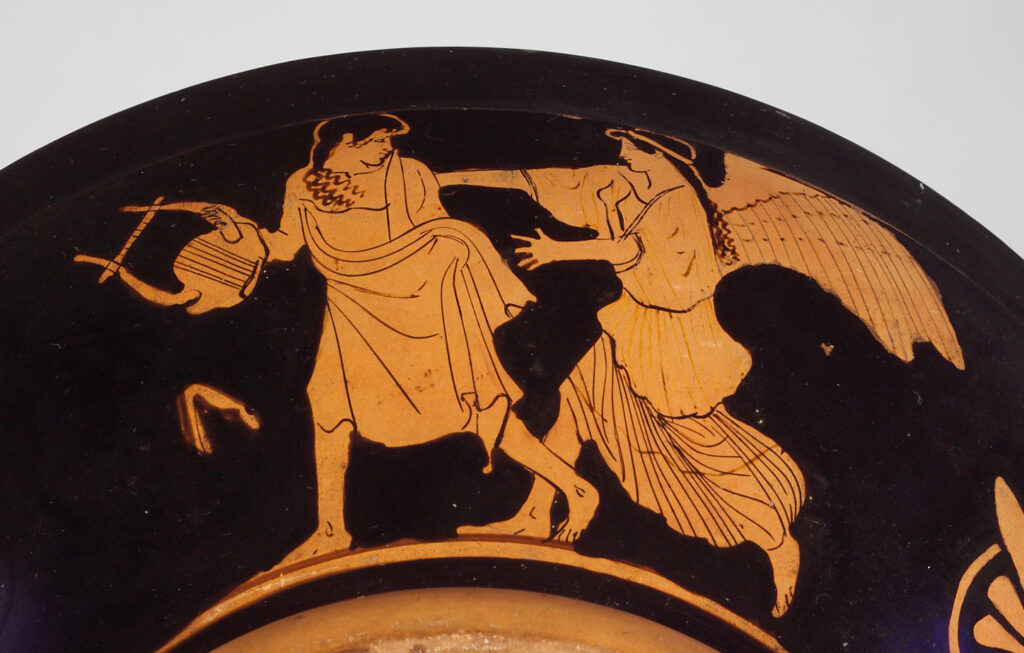

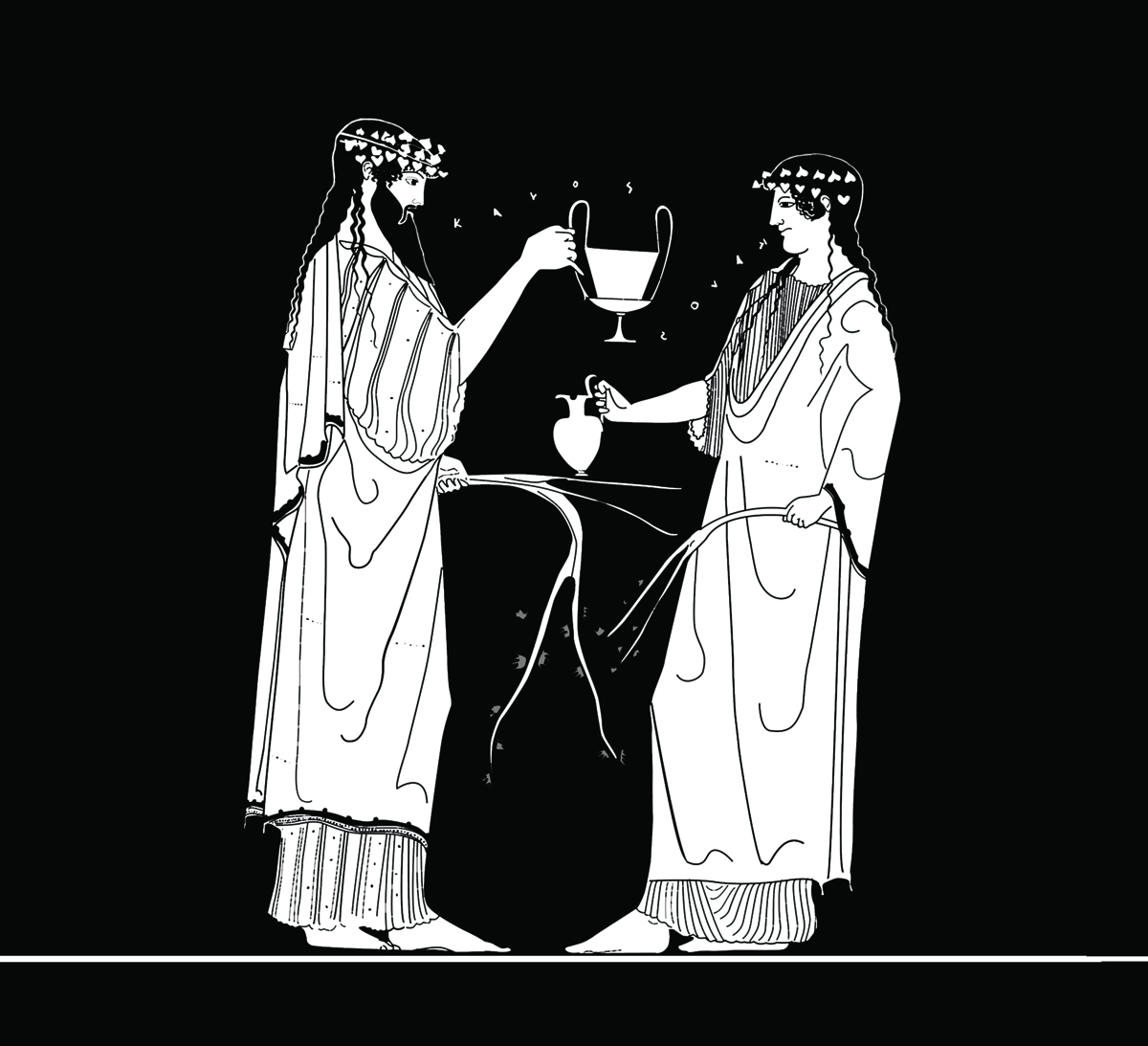

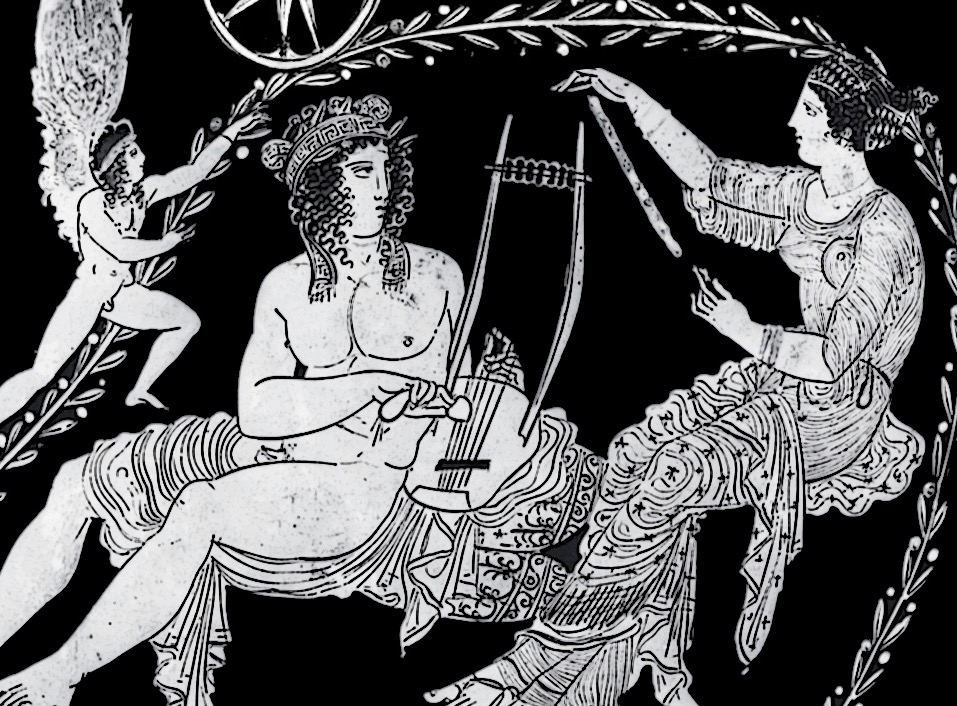

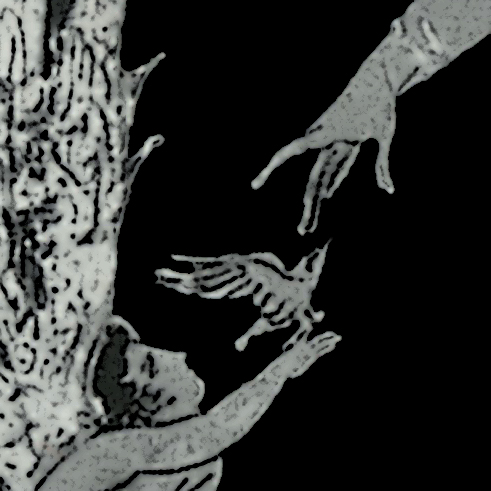

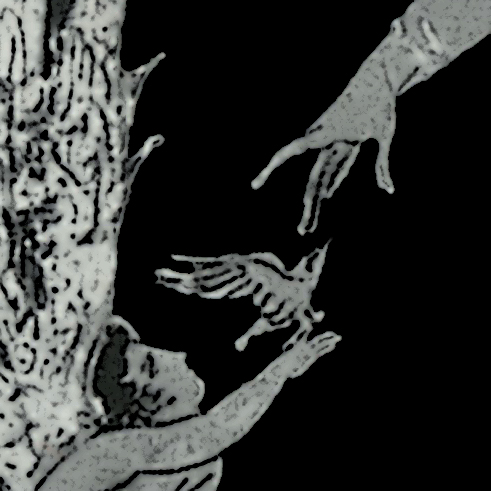

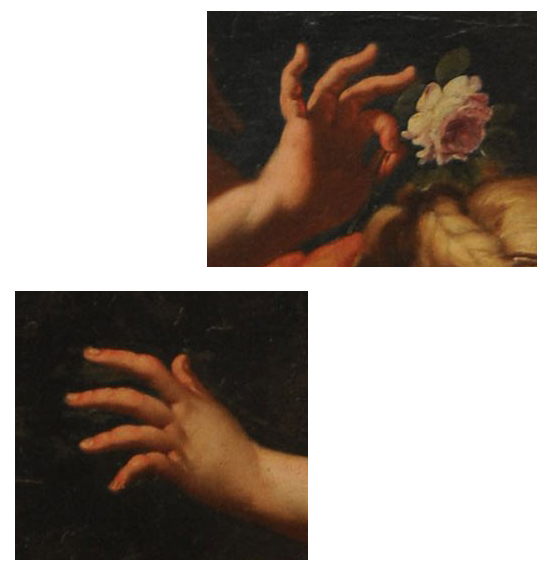

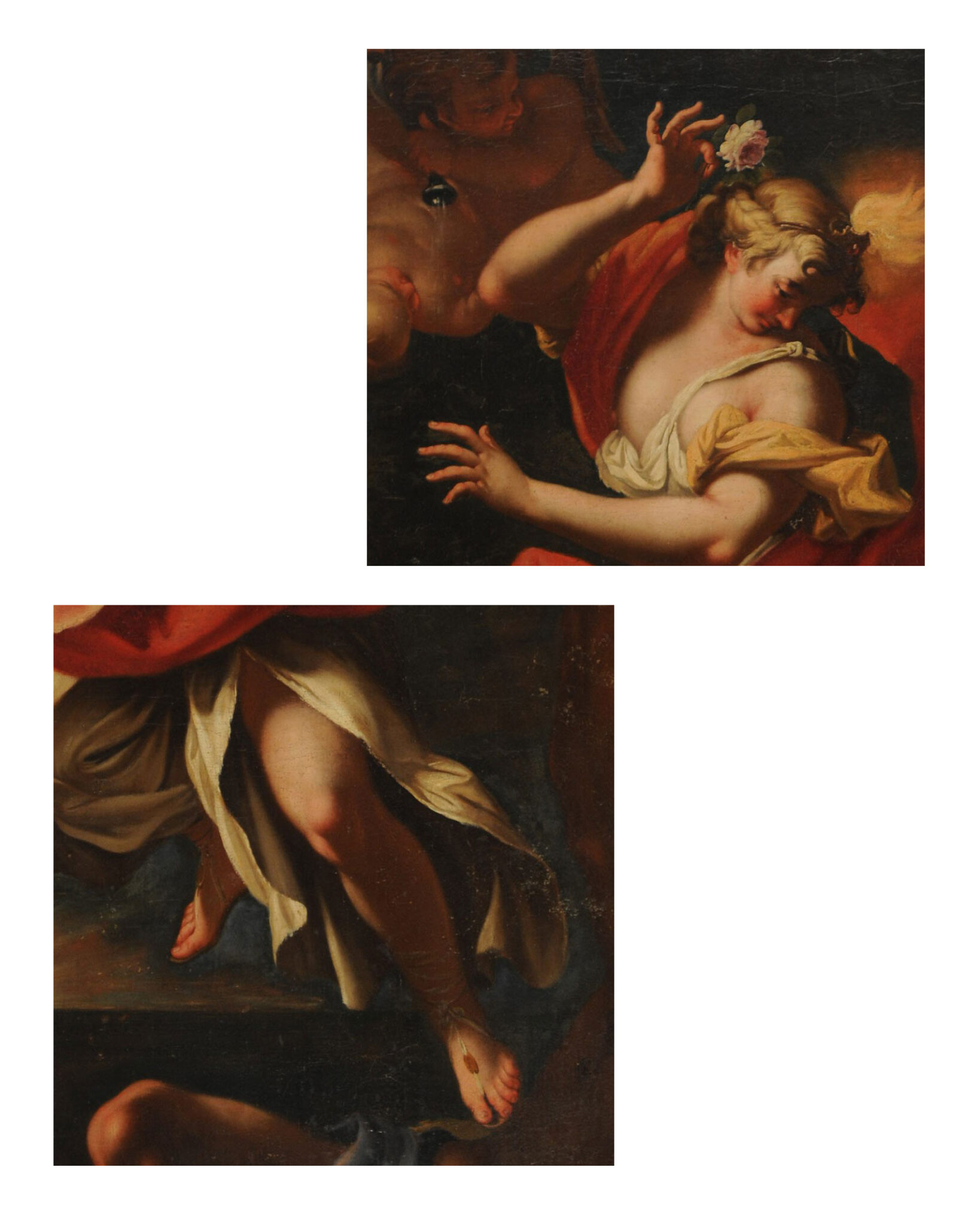

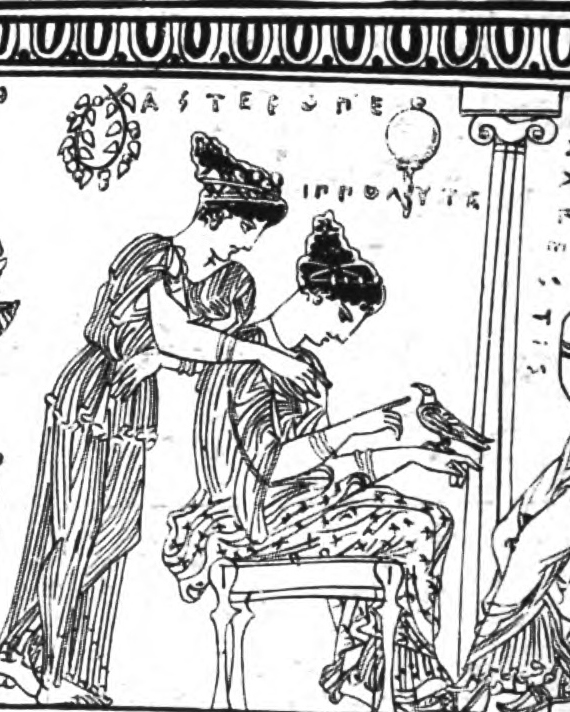

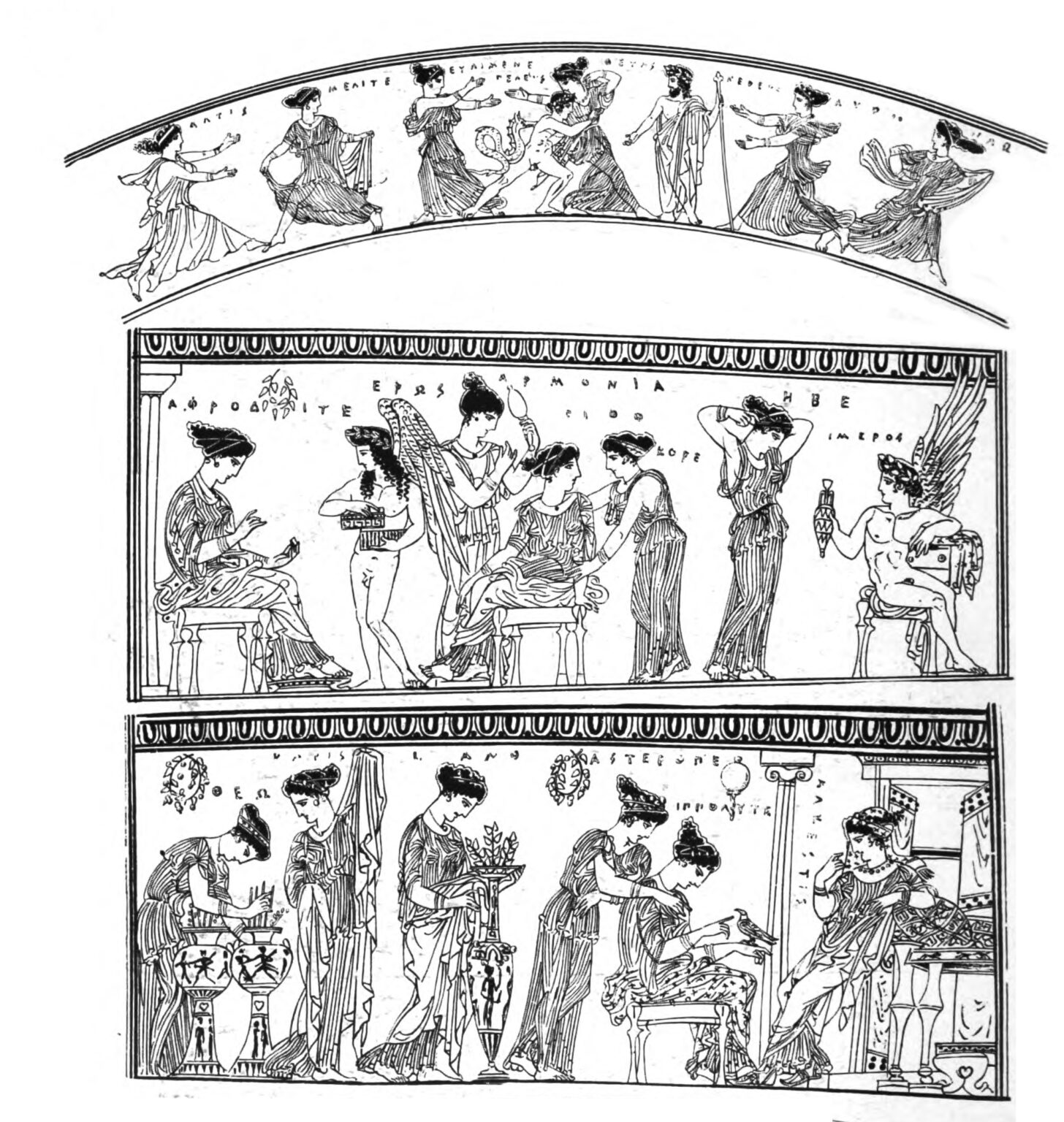

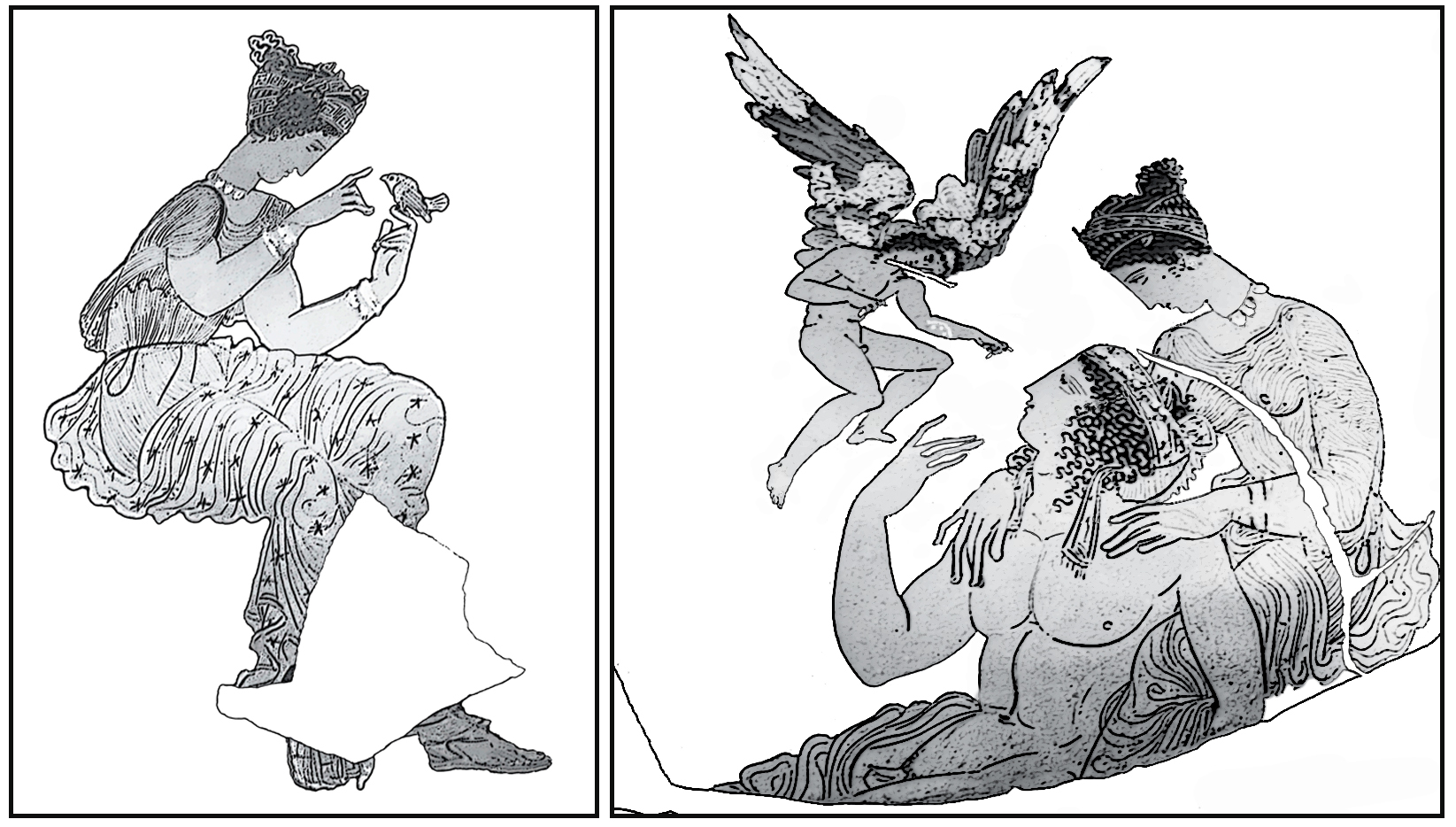

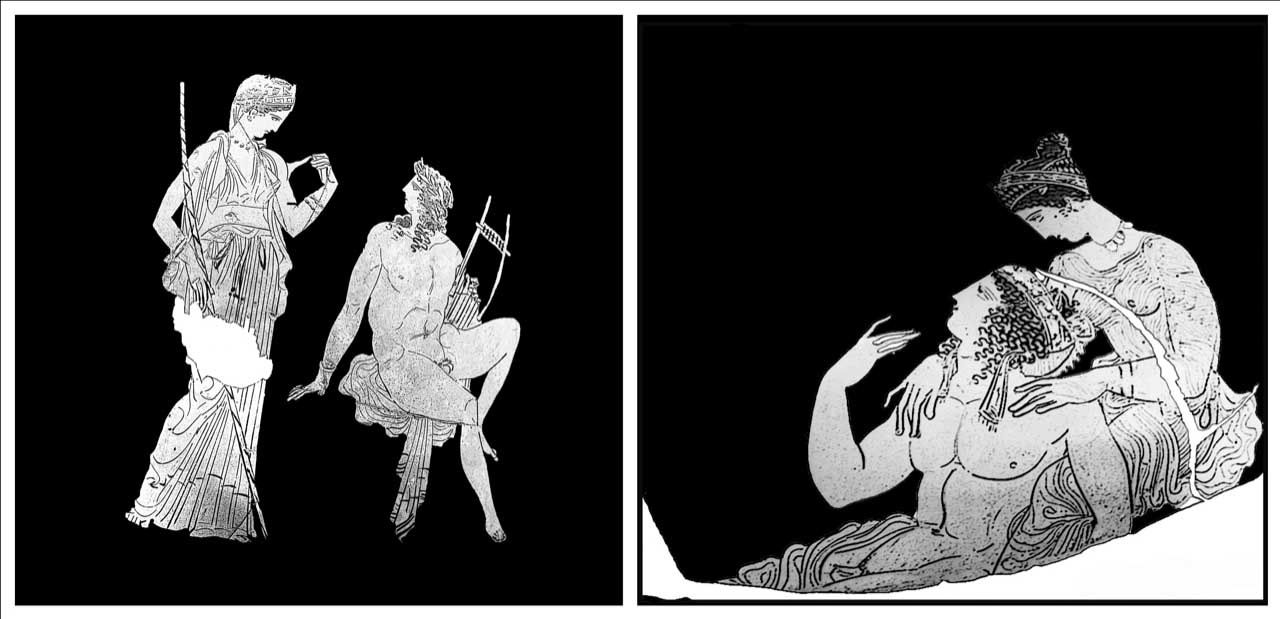

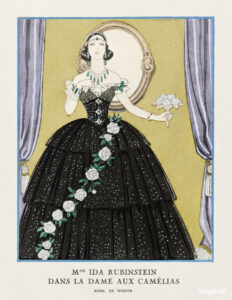

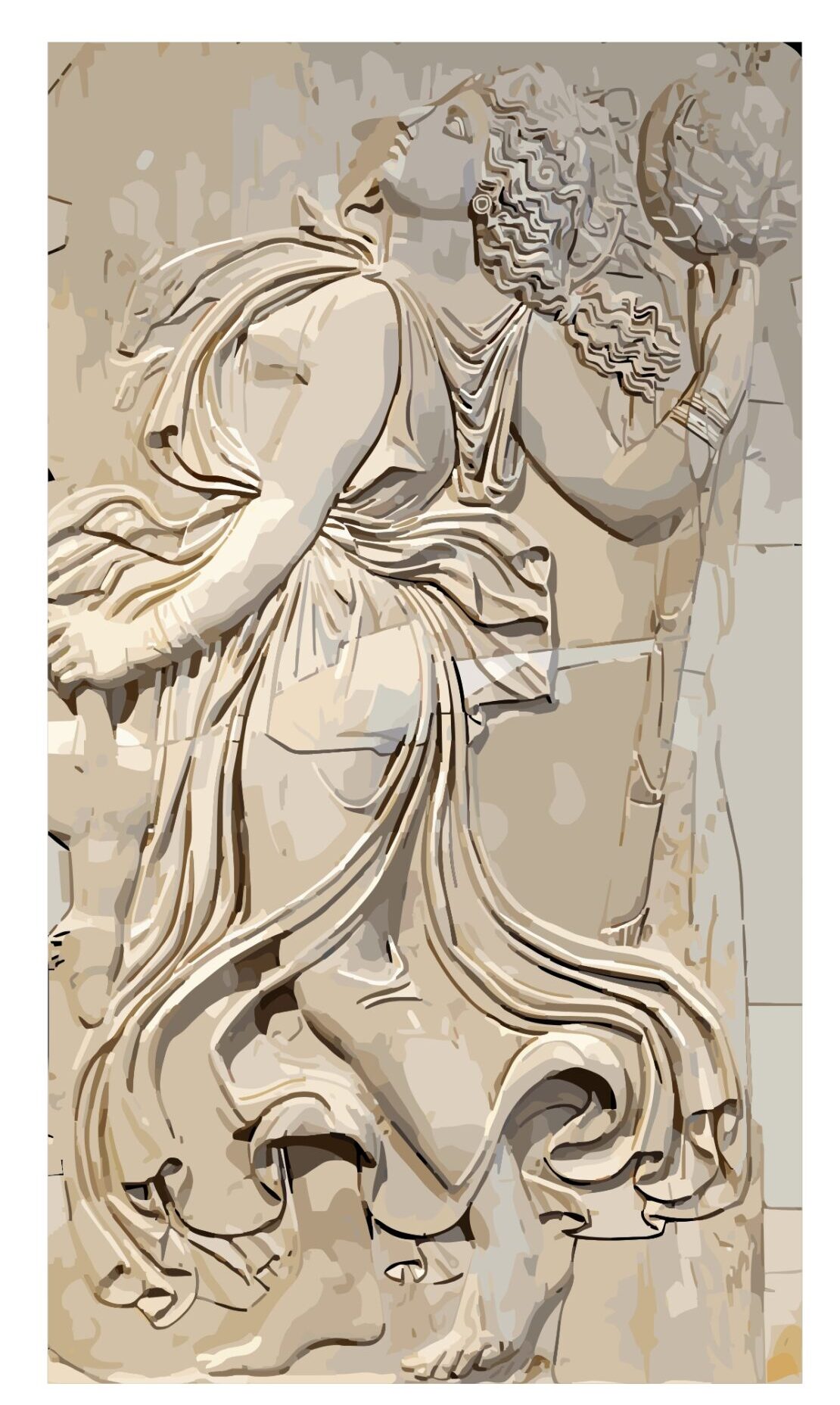

2§20. Pursuing further the idea of a Panathenaic context for the performance of songs attributed to Anacreon—and, by extension, of songs attributed to Sappho and Alcaeus—I highlight the evidence of two pictures painted on a red-figure vase of Athenian provenance. I have already shown, at the beginning of this book, a detail from one of these two pictures, and now I will show both pictures painted on the vase—but only after repeating what I wrote at the beginning about the vase itself. This vase, to repeat, is a “krater” shaped like a “kalathos,” made in Athens sometime in the decade of 480-470 BCE and painted by an artist known to art historians as the Brygos Painter. The vase is now housed in Munich, Antikensammlungen no. 2416; ARV2 385 [228]), but its original home had been the ancient Greek city of Akragas in Sicily, a city now called Agrigento in Italian. Accordingly, as I already said in the caption about this vase at the beginning of the book here, I continue to refer to this artifact simply as the Akragas Vase. The vase shows on its two sides paintings attributed to the so-called Brygos Painter. In what follows, I will analyze both pictures, as painted on the obverse and the reverse sides of this Akragas Vase, referring to line drawings of these pictures. These line drawings, which were originally made for me by Valerie Woelfel and which I will label Image 1 and Image 2, were first published in the printed version of the essay I list in the Bibliography as Nagy 2007|2009):[26]

2§21. In Image 1 we see two figures in a pointedly musical scene. The man who is figured on our left is playing the specialized string instrument known as the barbiton, while the woman who is figured on our right is playing her own barbiton. The lettering adjacent to the man identifies him as ΑΛΚΑΙΟΣ, that is, Alkaios =Alcaeus, while the lettering adjacent to the woman identifies her as ΣΑΦΟ, that is, Sapphō =Sappho. The two figures in the painting are described as follows by a team of art historians:

[They are] side by side in nearly identical dress. But under the transparent clothing of one – a bearded man – the sex [sic] is clearly drawn. The other is a woman – her breasts are indicated – but a cloak hides the region of her genitals, apparently distancing her from any erotic context. She wears a diadem, while the hair of her companion is held in a ribbon (tainia). Each holds a barbiton and seems to be playing. The parallelisms of the two figures, male and female, is unambiguous here. A string of vowels (Ο Ο Ο Ο Ο) leaving the man’s mouth {183|184} indicates song. An inscription, finally, gives his name, Alcaeus [ΑΛΚΑΙΟΣ], and indicates the identity of his companion, Sappho [ΣΑΦΟ] […] The long garment and the playing of the barbiton are […] connected with Ionian lyric. [27]

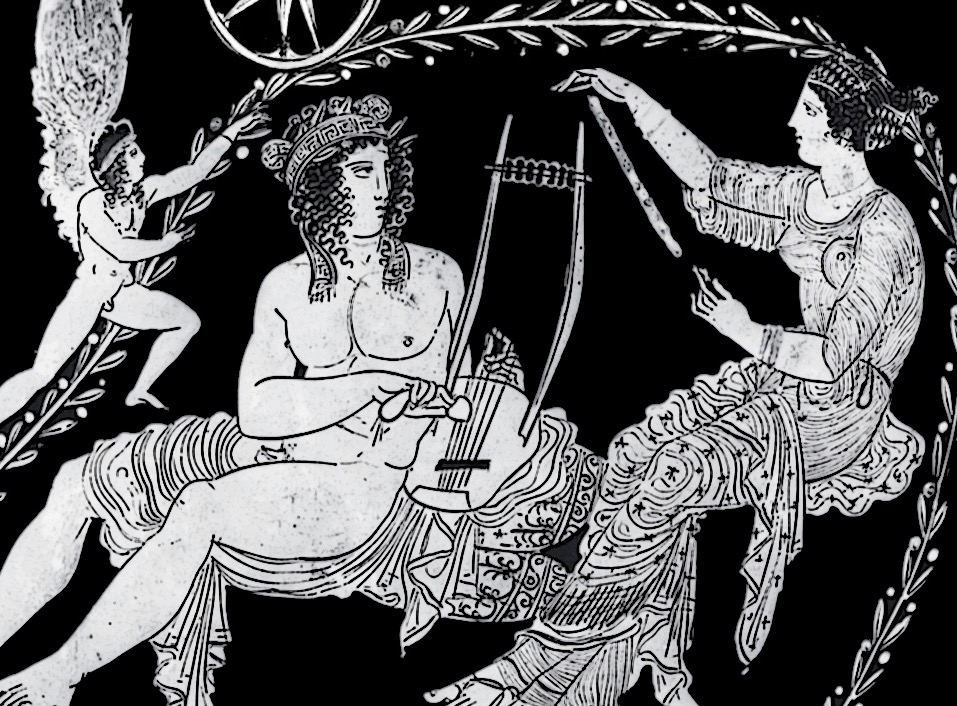

2§22. Next we turn to Image 2 as painted on the same Akragas Vase. Here we see two figures in a pointedly sympotic scene. The figure on our left is the god Dionysus, while the figure on our right is a female devotee, that is, a Maenad. Sympotic themes predominate. Dionysus, as god of the symposium, is directly facing the Maenad, who appears to be coming under the god’s possession, transfixed by his direct gaze. The symmetry of Dionysus and the Maenad is reinforced by the symmetrical picturing of two overtly sympotic vessels, one held by the god and the other, by his newly possessed female devotee: he is holding a kantharos while she is holding an oinokhoē. The pairing creates a sort of sympotic symmetry.{184|…}

2§22a. There is a homoerotic subtext at play in this picture, since the two facing figures, Dionysus and the Maenad, are both shown voicing, by way of lettering that emanates from their lips, the word ΚΑΛΟΣ, that is, kalos, a masculine-gender adjective meaning ‘beautiful’ and referring to an unnamed male referent. This erotic theme reinforces the eroticism that is built into the whole artifact, since this pot was made not for pouring wine. The spout at the base of the vessel, designed for a stopper that prevents leaking when there is no pouring to be done, was evidently designed, as we read in a formulation by the art historian Malcolm Bell (1995:28), for the pouring of honey from the spout at the bottom, not for the pouring of wine from the opening at the top: “the location of the opening at the bottom of the belly suggests that the contents issued from the spout when a cork or plug was removed, while the vase was sitting upright on a shelf or table.” The spout is clearly visible in the photograph of this vase that is featured at the beginning of Essay 27 here in Sappho II. Thus the Akragas vase was a “honey pot” (Bell p. 28n147 provides bibliography on attestations of such vessels), which was intended, I think, as a loving gift to an unnamed man described as kalos ‘beautiful’ by way of inscribed lettering that is spoken, as it were, by both Dionysus and his Maenad.

2§22b. I propose that the unnamed destinataire of this loving gift, the Akragas Vase, was Thrasyboulos of Akragas. I build here on argumentation I present in Sappho 0 (3§§65, 69, 73), where I follow a reconstruction, by Malcolm Bell (again, 1995), of relevant historical events: he links the Akragas Vase with a marble statue known to art historians as the Motya Charioteer. Both artifacts were custom-made by Athenian artisans sometime in the decade of 480–470 BCE, and both had been commissioned as artistic trophies intended for members of the dynastic family of the Emmenidai in Akragas—most likely for Xenokrates, tyrant of Akragas, and for Thrasyboulos, his son.

2§22c. As I also point out in Sappho 0 (3§70), Bell’s article (again 1995:16) links the Akragas Vase and the marble sculpture known as the Motya Charioteer with a third artistic trophy commissioned by the Emmenidai of Akragas: it is the song that we know as Pindar’s Isthmian 2. This song was commissioned to celebrate the victory of a four-horse chariot team sponsored by Xenokrates of Akragas in a chariot race that took place at the biennial festival of the Isthmia—most probably it was the festival held in the spring of 476; the same Isthmian victory is also mentioned in Pindar’s Olympian 2 (lines 49–51), which in turn celebrated the victory of a four-horse chariot team sponsored by the brother of Xenokrates, Theron of Akragas, in a chariot race that took place at the quadrennial festival of the Olympia in the summer of 476. According to the Pindaric scholia, the reference in Pindar’s Isthmian 2 (line 3) to paideioi humnoi‘songs of boys/girls’ is actually a reference to songs composed by the poets Alcaeus, Ibycus, and Anacreon (ταῦτα δὲ τείνει καὶ εἰς τοὺς περὶ Ἀλκαῖον καὶ Ἴβυκον καὶ Ἀνακρέοντα). As I argue in Sappho 0 (3§70), this reference in Pindar’s Isthmian 2 (line 3) must have included Sappho. As we have already seen, pais can mean not only ‘boy’ but also ‘girl’—as in the songs of Sappho. {…|185}

2§22d. Just as the “honey pot” can be seen as an eroticized gift to Thrasyboulos, so too the victory ode of Pindar that we know as Isthmian 2, presents itself as a gift to this same Thrasyboulos, who is addressed by name already in line 1 of the song. The song eroticizes itself as a sweet gift by referring to the poet’s Muse, Terpsichore, as ‘having the sound of honey’ (line 7: μελιφθόγγου… Τερψιχόρας)—and by referring to sympotic songs as melikomptoi ‘honey-sounding’ (line 32: μελικόμπων ἀοιδᾶν). As Bell notes (p. 28), the whole song is suffused with metaphors of sweetness. Even the sympotic songs of old that Pindar idealizes as paideioi humnoi ‘songs of boys/girls’ are described as meligārues ‘having the voice of honey’ (line 3: παιδείους … μελιγάρυας ὕμνους).

2§22e. And the honey-sweetness of songs sung amorously at symposia is matched by the picturing of Alcaeus, as painted on the surface of the honey pot that I am calling the Akragas Vase, since Alcaeus is imagined here as singing an amorous song to Sappho. There has actually survived a fragment of such a song, addressed by the figure of Alcaeus directly to the figure of Sappho:

ἰόπλοκ’ ἄγνα μελλιχόμειδε Σάπφοι

Alcaeus F 384

You with strands of hair in violet, O holy [(h)agnā] one, you with-the-honey-sweet-smile [mellikhomeide], O Sappho!

The honey-sweet words of Alcaeus are attempting, maybe in vain, to captivate the goddess-like Sappho, addressed here as ‘smiling with a smile that is honey-sweet’, mellikhomeide (μελλιχόμειδε).