2024.05.28, rewritten from Classical Inquiries 2016.03.03 | By Gregory Nagy

This pre-edited standalone essay, rewritten for online publication in Classical Continuum, originally appeared in Classical Inquiries 2016.03.03. My rewritten version here supersedes the original version, partly because my online contributions to Classical Inquiries, extending from 2015.02.14 to 2021.10.13, are currently not being curated by the Center for Hellenic Studies.

Introduction

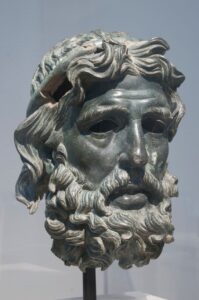

§0.1. This essay centers on a bronze statue of a head, dated somewhere between 227 and 221 BCE. The bronze head was on display at the National Gallery of Art in Washington DC, on loan from the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, in the context of a grand exhibition at the National Gallery, titled “Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World” and extending from December 13, 2015, to March 20, 2016. Together with Gloria Ferrari Pinney and Faya Causey, I was involved as a co-organizer of two public events focusing on two aspects of the exhibition. These events were panel discussions of two topics:

February 18, 2016: “A priestess or a goddess: The problem of identity in some female Hellenistic sculptures.”

February 25, 2016: “A poet or a god: The iconography of certain bearded male bronzes.”

About these two events I refer to overall reports, originally published in Classical Inquiries, by Keith DeStone, and now rewritten by him here:

At the second of the two events cited here, my friend Gloria Ferrari Pinney—hereafter I refer to her, in honor of our friendship, simply as Gloria—argued that the bronze head on loan from Houston is a representation of Homer. At the same event, I too offered supporting arguments, which were first published in my original essay of 2016.03.03 in Classical Inquires. As I now rewrite my essay, I must start by noting, with deep regret, the untimely death of Gloria in 2023.09.18, which now leaves me with the sad task of trying to sustain the essence of her argumentation without the benefit of any further consultation with her. I fear I can do no better than restate, as faithfully as possible, my memories of what Gloria had said about the bronze head in 2016.02.25. Taking my lead from what she did say, I will argue here that this bronze Homer—if indeed he is Homer, as I think he must be—is in this case imagined not only as the greatest of all poets but also as a cult hero.

§0.2. An essential aspect of GFP’s argument is the fact that the Houston bronze head resembles closely the head of the god Zeus himself as represented in statues and coins. In terms of this argument, Homer is figured as the greatest poet of the ancient Greeks just as Zeus is figured as their greatest god.

§0.3. There is further evidence, as Gloria shows, for the artistic construct of such a resemblance between Homer and Zeus. A most telling example is a marble monument known as the Arkhelaos Relief, conventionally dated to the second century BCE. The lower zone of the relief sculpture shows an enthroned Homer receiving sacrificial offerings while the upper zone shows Zeus himself, holding a scepter. Similarly, Homer holds a scepter, which is in his left hand. Also, he holds a scroll in his right hand. There is no mistake about the identification of Homer here, since the Arkhelaos Relief features adjacent lettering that reads ΟΜΗΡΟΣ (Homēros). We see comparable representations of an enthroned Homer as pictured on two coins, one from the city-state of Smyrna, reputed to be the place where he was born, and another from the island-state of Ios, where he was supposedly conceived—and where he died.

Smyrna, 190-130 BCE. Pictured is the poet Homer, seated and holding a staff and a scroll. ΣΜΥΡΝΑΙΩΝ = ‘of the people of Smyrna’. Named is a magistrate, AXIΛΛHTOΣ [A]XIΛΛHTO[Υ] = ‘Akhilletos, son of Akhilletos’. Pictured on the other side of the coin is the laureate head of Apollo. Classical Numismatic Group, Inc. http://www.cngcoins.com

Ios, 4th century BCE. British Museum number 1951,1007.8. Obverse: pictured is the bearded head of Homer, bound with a fillet; inscription OMHPOY = ‘of Homer’. Reverse: garland; inscription IHTΩN = ‘of the people of Ios’.

Picturing Homer as blind or as sighted

§1. As Gloria Pinney argues, the artistic construct of such a resemblance between Homer and Zeus comes with a requirement: Homer must be pictured as sighted, not blind. If Homer is to be compared to Zeus, he cannot be deformed by blindness, since the greatest of all gods must surely be exempt from such deformity.

§2. But there are well-known examples of an alternative artistic construct that features Homer as blind, and this construct is amply attested in the visual arts. Further, such an artistic construct of a blind Homer matches what we read in the stories produced by the verbal arts of mythmaking about Homer’s life. In those stories as I analyzed them in an essay dated 2016.02.25 and, in an earlier essay dated 2016.02.18, Homer in various different ways becomes a blind man in the course of his life. So, the question arises: what is the difference between a blind Homer and a sighted Homer?

§3. If we follow the logic of the artistic construct that we see at work in the Arkhelaos Relief, the enthroned Homer as pictured in that relief must surely be situated in a state of existence that follows his death. In other words, Homer now exists in an afterlife. That is why the Arkhelaos Relief has been thought to represent what is called the “apotheosis” of Homer: it is as if the greatest of poets had now become a theos or ‘god’, just as Zeus is a god.[1] And, in this transcendent state, Homer regains his vision. Here is a close-up of this transcendent Homer as represented in the Arkhelaos relief:

Picturing Homer as a cult hero

§4. I argue, however, that Homer in such a state of afterlife is not so much a god as he is a cult hero who looks like a god. Here I find it most useful to consult a book by W. H. D. Rouse on the iconography of votive offerings.[2] He collects images of cult heroes in the afterlife who are pictured as enthroned or reclining or engaged in other such poses.[3] In each case, as Rouse shows, the pose is matched by gods who are similarly engaged: in one particular case, Rouse describes the picturing of a reclining hero “with face approaching that of Zeus or Hades.”[4]

§5. Just as the enthroned Homer in the Arkhelaos relief receives sacrificial offerings from his worshippers, so also the enthroned cult heroes in the collection put together by Rouse are seen in the act of receiving offerings from their worshippers. Here is an example:

Bibliography

Clay, D. 2004. Archilochos Heros: The Cult of Poets in the Greek Polis. Hellenic Studies 6. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC.

H24H. See Nagy 2013.

Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013.

Rouse, W. H. D. 1902. Greek Votive Offerings: An Essay in the History of Greek Religion. Cambridge.

Notes

[1] For a brief history of this terminology, which also inspired the painting “L’Apothéose d’Homère” by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1827), see Clay 2004:1.

[2] Rouse 1902.

[3] Rouse 1902:20, 34 (heroes enthroned); 22 (heroes reclining).

[4] Rouse 1902:22.