2021.11.10 | By Natasha Bershadsky

There are two girls, or young women, portrayed on John Roddam Spencer Stanhope’s painting called Penelope. Both are barefoot; neither is cheerful.

One, who is seated, is chestnut-haired; her hair is plaited in a crown of braids. She sits pensively next to a piece of woven fabric (which I will call a web, honoring the word’s etymology), a brown thread gently held in her left hand. The thread leads to the name Odysseus, appearing in capital Greek letters on the web. She wears a pale red skirt.

Another is standing. Her hair is bright auburn and hangs loosely along her back. With a look of quiet focus, she pulls a tree branch down with her left hand; there is a golden fruit grasped in her right hand. She wears a blue dress.

Who are these two figures? Their white arms are painted in a way that creates a connection between them. Both have their left arm bared up to the shoulder and slightly bent; in a juxtaposition, the blue girl’s left arm is raised in action while the red one’s is lowered, lying obliviously in her lap (but still holding the thread). The right arms: both bare up to the elbow; both lifted up vertically. Blue girl’s fingers are downturned; red girl’s palm is facing up, cradling her cheek.

Some accounts identify the blue-dressed girl as a maidservant of Penelope, the one who revealed her deception of unweaving to the suitors. There is a clear contrast between the modest braided hair of the seated girl and the loose locks of the standing one, whose grasping of the fruit also indicates an appetite.[1] Yet the two figures are too similar in stature, in features, and in arm gestures to interpret them as a mistress and a maid. They seem more like twins. Could they be two versions of the same person, the free girl of the past and the melancholy woman of the present? In a different take, Simon Poë has suggested that both figures were inspired by the same model, Stanhope’s wife, who was a young war widow before her marriage to the painter:[2] so the melancholy woman would belong to the past, while the fruit-desiring beauty would be the current version.

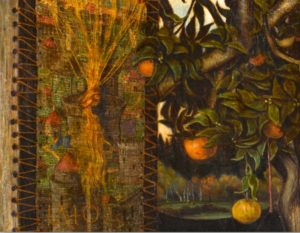

There are two corresponding figures threaded into the web. One wears red, another wears blue; both have their right arms bare, but the hair hues have been changed around in comparison to the characters on the exterior: the red figure has a golden coiffure, while the blue one seems to sport a darker shade. The name Brisēis is written on the skirt of the blue figure. The figure wearing red holds the beginning of a golden streamer inscribed with words (a banderole), winding around the two figures; the name Chrusēida is visible on it where the two figures’ white arms cross.

So the little figures are Briseis, wearing blue, and Chryseis, with the golden hair.[3] In the world of Penelope’s web, they are looking up at something with alarm. Pictured above them in the web are dark walls and towers of a fortified city, identified by two sets of gigantic letters, one blue and one golden: ILIO…, ILIOS: Ilion/Ilios, Troy.

Before we proceed further, let us read the letterings pictured in the web. A thin blue stripe under the walls of the city reads Skamandros, the river Scamander. But it’s the winding banderole that carries most of the letterings. The text starts with the words of Iliad 1.309–311: I underline the words or parts of words that appear on the tapestry:

ἐν δ’ ἐρέτας ἔκρινεν ἐείκοσιν, ἐς δ’ ἑκατόμβην

βῆσε θεῷ, ἀνὰ δὲ Χρυσηΐδα καλλιπάρῃον

εἷσεν ἄγων·

…[Agamemnon] chose a crew of twenty oarsmen, and sent a hecatomb

for the god. Moreover, he escorted fair-cheeked Khrysēis on board.

The middle part of the banderole continues where the previous part left off (Iliad 1.311–313):

ἐν δ’ ἀρχὸς ἔβη πολύμητις Ὀδυσσεύς.

Οἳ μὲν ἔπειτ’ ἀναβάντες ἐπέπλεον ὑγρὰ κέλευθα,

λαοὺς δ’ Ἀτρεΐδης ἀπολυμαίνεσθαι ἄνωγεν·

And Odysseus, intelligent in many ways, went as the leader.

Then they went on board and started sailing along the watery pathways.

But the son of Atreus bade the people purify themselves; …

Finally, a tiny fragment of text on the lower end of the banderole (mbas…getoio…)[4] seems to belong to the same passage (Iliad 314–317):

οἱ δ᾿ ἀπελυμαίνοντο καὶ εἰς ἅλα λύματα βάλλον,

ἕρδον δ᾿ Ἀπόλλωνι τεληέσσας ἑκατόμβας

ταύρων ἠδ᾿ αἰγῶν παρὰ θῖν᾿ ἁλὸς ἀτρυγέτοιο·

κνίση δ᾿ οὐρανὸν ἷκεν ἑλισσομένη περὶ καπνῷ.

so they purified themselves and cast their impurities into the sea.

Then they offered to Apollo hecatombs

of bulls and goats without blemish on the shore of unharvested sea,

and the smoke with the savor of their sacrifice rose curling up towards the sky.

The scroll of the banderole quotes the first passage of the Iliad where Odysseus appears,[5] but what is its relevance to the two figures outside of the pictures threaded into the web?

Faced with a reference to Penelope’s weaving and unweaving, I find it natural to think about completeness and incompleteness. The passage from the Iliad describes an action of completion: in a peacefully curling smoke of the sacrifice, we come to the story’s end as far as Chryseis is concerned. She returns to her father, forever preserved as a figure of a maiden. But at the same time for the Iliad as a whole, that is just a beginning. For Briseis, already a widow, being taken away from Achilles is neither a beginning nor an end, but a new twist of the thread; and hers is one of those stories whose end we never learn. What happens to Briseis when Achilles is dead? We lose any trace of her.

Penelope’s brown thread, leading to Odysseus’ name in the web, suggests that her activity is imagined by Stanhope not as weaving and unweaving, but as embroidering and unpicking the embroidery. Penelope creates the lines that identify the little figures on the web—or let us call it the tapestry—and these figures are the miniature images of herself and her opposite-twin. But there is something else on the tapestry that seems fixed, not changeable; and it is toward that fixed feature that the gazes of the little figures appear to be pointing anxiously. The golden threads of the tapestry’s warp are tied in a loose knot and hang down, partly obscuring the towers of Troy. Their color and their texture are identical to the bright hair of the fruit-picker; they are also the same color as the golden fruit, which we can recognize as oranges (given the tree’s leaves, blossoms, and pieces of the rind lying on the ground). The loose golden hair, the color of orange, the girl’s loveliness, and her craving are all linked with the tapestry’s constitution, its warp. But they are also part of the story: the golden strands overhanging the towers of Troy look like a raging fire that is burning Troy up. That is the source of terror in the upturned faces of Briseis and Chryseis. It is of course Helen who is the loveliness and the terror, the beginning and the ending of the story. Briseis and Chryseis, caught in the story, are helplessly watching the fire; their figures in a golden winding banderole resemble the sons of Laocoon being suffocated by the serpent.

Bibliography

Poe, Simon. 2002. “Penelope and her suitors: women, war, and widowhood in a pre-Raphaelite painting.” The Journal of Pre-Raphaelite Studies 11:68–79.

[1] https://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2017/victorian-pre-raphaelite-british-impressionist-art-l17133/lot.8.html.

[2] Poë 2002, 70–71.

[3] Poë 2002, 71.

[4] The lowest four letters, ssēs, do not seem to belong to this passage from the Iliad: perhaps we should imagine them as a part of the word thalassēs, ‘of the sea’?

[5] Poë 2002, 70–71.