Edited by Rachele Pierini and Tom Palaima

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Winter session of the MASt seminars by welcoming the participants to the February meeting. Before entering into the heart of the Winter MASt talks, all the participants joined the MASt organizers in congratulating Marie Louise Nosch, a steady member of the MASt network, for her latest exceptional achievement of high-profile awards. Nosch has been the 2022 recipient of the Gad Rausing prize, the most important prize of the Swedish Academy of Science. Here is the Gad Rausing prize official web site, with the full description of the awards and the motivations. Congratulations Marie Louise!

Little things make big things happen—Aegean textiles and the EuroWeb COST Action CA 19131 ‘Europe through Textiles. Network for an integrated and interdisciplinary Humanities’

EuroWeb COST Action CA 19131

§8. All COST Actions aim to achieve their objectives through sharing, creation, dissemination and application of knowledge organized via the work of Working Groups. The main aims and objectives of the EuroWeb are to be fulfilled with the help of four Working Groups and their leaders:

- WG 1 Textile Technologies (leader: Christina Margariti): technology behind textiles through instrumental analysis, textile tools, experimental archaeology, traditional crafts and conservation;

- WG 2 Clothing Identities (leader: Magdalena Woźniak): gender, age and status: meaning of clothing through ages, areas and cultures; a key to explain values in society and to understand individuals, self-representation, and groups;

- WG 3 Textile and Clothing Terminologies (leader: Louise Quillien): exploring and comparing the vocabulary of textiles and garments in Europe and its neighbors, across time;

- WG 4 The Fabric of Society (leader: Francesco Meo): economic and agricultural impact of textile production and consumption; the basis for textile crops and trade by tracing textile trade patterns and paths through Europe and through time.

Studies on Aegean textiles as the ‘new black’

Textiles from Bronze Age Greece—highlights

§15. Due to the specific preservation pattern for excavated textiles and their impressions, there are several notable discrepancies among the evidence of actual textiles, textual and iconographic evidence, and general knowledge of Aegean textile technology resulting from other archaeological and experimental data. For example, the economic and symbolic importance of wool, commonly considered as the innovative and even revolutionizing raw material, is well attested by the Linear B tablets, [11] but very poorly evidenced among the extant textiles. Woolen fabrics are known from Middle Bronze Age Eleon [12] and Akrotiri, [13] and Late Bronze Age or Early Iron Age Stamna [14] and Lefkandi. [15] Similarly, patterned, multicolored and diaphanous textiles, so distinct in the imagery, especially in wall paintings, are almost not attested at all by the excavated textiles. Exceptions are fragments again from Lefkandi. These display chevron pattern, tapestry, soumak and pile knotting technique. [16] Traces of other decorative techniques, such as the use of supplemental thread and stitch are attested by fragments from Akrotiri, [17] Eleon, [18] and one textile impression on the cast from Phaistos (Figure. 2). [19] Also purple-dyed textiles are indeed few in number, [20] although purple-dyeing industry, both small- and larger-scale, is well confirmed at several Aegean sites, especially on Crete. The preserved evidence comprises finds of crushed Murex shells, dyeing installations, [21] the actual presence of the purple pigment in wall paintings [22] and residues of Murex dye on pots from dye-works. [23]

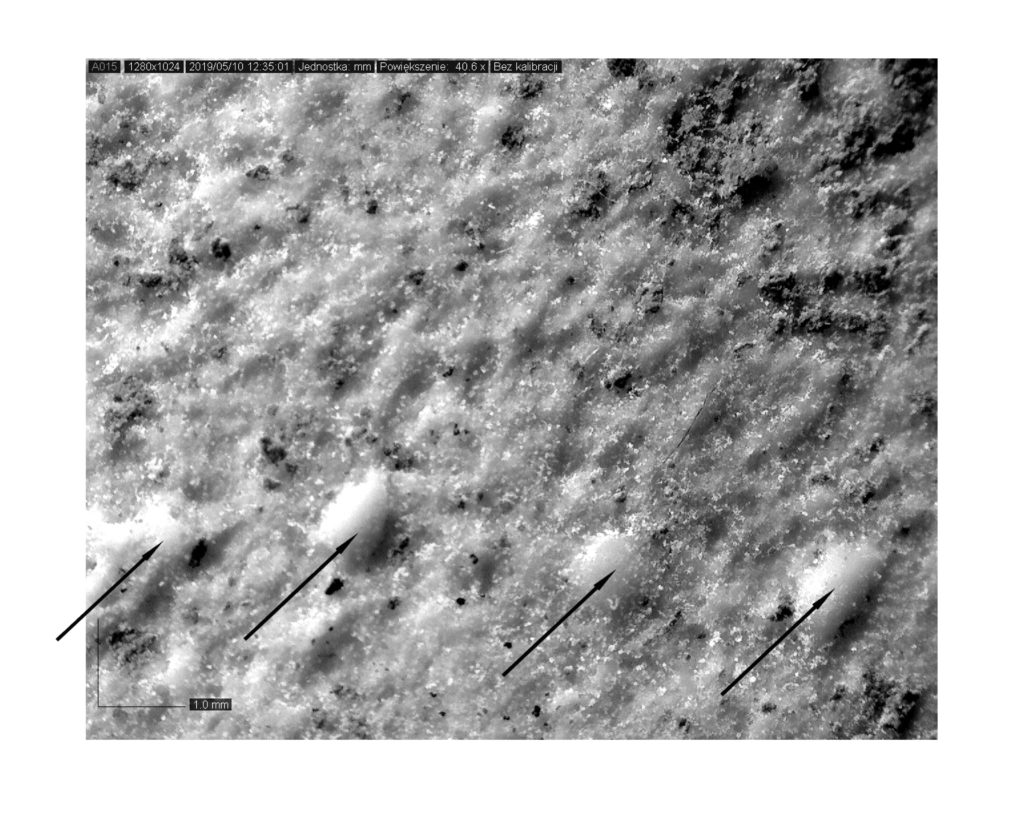

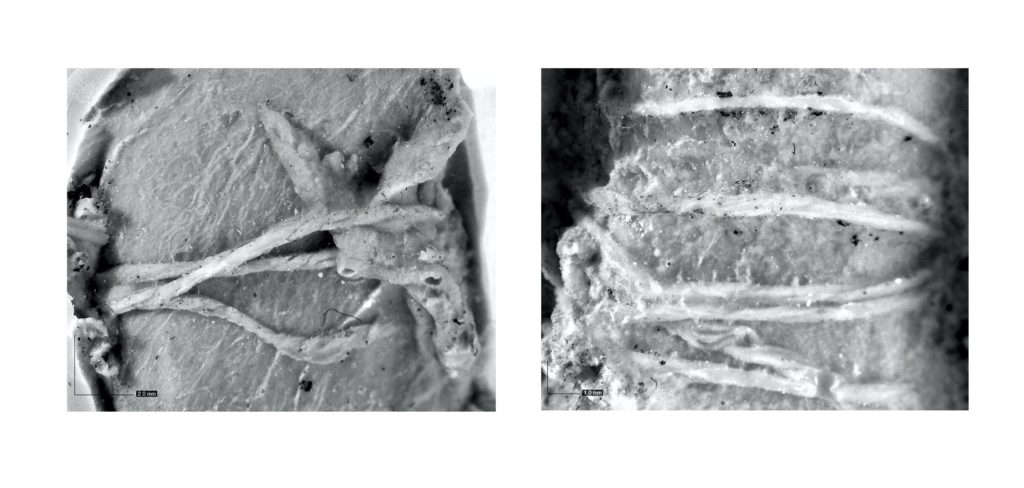

§16. Except for Lefkandi, all the preserved textiles, regardless of their date, origin and function, were made in a tabby weave, which seems to constitute an important characteristic of textile culture(s) in Greece in the Bronze Age and possibly beyond. [24] More technological variety, however, has been observed in techniques for making yarns and threads. Recent research on the European and Near Eastern textiles implies that splicing was the oldest technique for making threads of plant-origin fibers, such as tree-bast and fibers from plants of fibrous stems. Draft spinning, the technique suitable for short fibers such as wool, was a later innovation, however both techniques must have been in use in the Bronze Age. [25] In Greece, the earliest examples of spliced yarns come from the first millennium BCE, but characteristic features for splicing have been observed in textiles from Mycenae [26] and on imprints of fine threads on the CMS casts (Figure 3). In excavated textiles from Bronze Age Greece, yarns have been identified as S-plied of z-twisted single elements. [27] However, textile impressions from the undersides of clay sealings, especially the ones from Middle Bronze Age Phaistos, provide information about Z-plied and braided threads and cords, implying that more techniques might have been in use at one site in the same chronological and functional contexts. [28]

Textile tools—highlights

Iconography of textiles and clothing—highlights

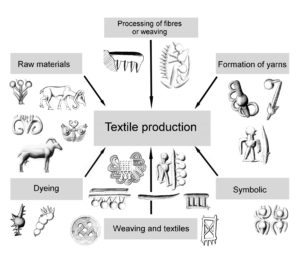

§21. Iconography of textile production is less frequent and almost exclusively limited to Aegean seals. The entire network of semantic references to textile manufacturing has been revealed by the “Textiles and Seals” project (Figure 4). [40] Textile motifs have been recognized based on a visual resemblance of motifs to their potential real-world references: actual fibrous plants, woolly animals, tools, tasks, etc. Characteristic features specific for each referent and motif, such as the shape of stem, leaves, crown and seed capsules in flax plant and ‘flax motif’, shape of head, horns, ears, tails, presence of fleece in woolly animals and ‘woolly animal’ motifs, features of functional significance such as loom weights as a part of a warp-weighted loom and specific technical gestures, have been distinguished in order to test the validity of new interpretations.

Figure 4. Network of potential real-world references to textile production on Aegean seals. A. Ulanowska, seal drawings after the CMS Arachne database.

EuroWeb and Aegean textiles: concluding remarks

Comments following Ulanowska’s presentations

§28. Nosch and, simultaneously, Natasha Barshadsky highlighted that the above-mentioned Bennett’s book also contains the analysis of a metal geometric belt, now situated at the Harvard museum, that shows plates of metal with leather and stitching.

§34. Ulanowska’s Bibliography

Thoughts on Landscape, Religion, and Toponymy in the Pylian Archive

§35. Since the 2007 field season, the Mt. Lykaion Excavation and Survey Project has been investigating the Mycenaean levels of the Ash Altar, located on the southern peak of the mountain at 1,382 masl (Romano and Voyatzis 2014). Cult activity on the peak was continuous from the Late Helladic II period until at least the Hellenistic era, and the use of the site extends back even further in time, as material dating from the Late Neolithic, Final Neolithic, and Early and Middle Helladic periods could very well imply earlier ritual activity. Analysis of the burnt thigh bones of sheep and goats has yielded the earliest radiocarbon date of 1527 +/- 97 BCE, and the Ash Altar accordingly presents us with one of the oldest archaeological records of ritual thysia (Starkovich et al. 2013; Mentzer et al. 2017).

Comments following Mahoney’s presentations

§61. Greg Nagy observed that, in light Sanskrit, agros seems to deal with uncultivated land (rather than cultivated land). However, Nagy continued, agros could mean ‘hunting’, or ‘cultivating the land’ in examples like Meleagros in Illiad 9, as he argued in his piece The Origins of Greek Poetic Language: Review (part II) of M. L. West’s Indo-European Poetry and Myth (Oxford 2007):

§65. Regarding the connection between a-ko-ro and the meaning of uncultivated, Palaima shared a passage from a recent paper: