Untangling linguistic riddles: Mycenaean Greek terms in -eus and the new Anatolian language of Kalašma

Paper and Summary of the Discussion held at the Winter 2024 MASt Seminar (Friday, February 9)

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Winter 2024 session of the MASt seminar by welcoming the participants to the February meeting, which fully focused on linguistics.

§2. Both talks analyzed exciting linguistic riddles. Torsten Meissner talked about ‘The Greek nouns in -eus. Some further thoughts and recent developments’, focusing on the origins of nouns in -εύς in Greek. Elisabeth Rieken, in collaboration with Ilya Yakubovich, gave a presentation titled ‘On the Language of Kalašma: A New Indo-European Anatolian language’, centered on a cuneiform tablet found at the Boğazköy-Hattusha archaeological site.

§3. More than 150 years after their origin was first discussed, the nouns in -εύς remain one of most controversial and complex categories of Greek word formation. As such, Meissner’s talk re-examined some of the Mycenaean and early 1st millennium Greek evidence, both appellative and onomastic, so as to advance the understanding of the status of these formations in early Greek. On this basis, he discussed some of the proposals advanced regarding the origin of these nouns. While Meissner had not yet arrived at firm conclusions as to the origin of the formations, he put forward some areas for future research and some suggestions.

§4. Great excitement followed the recent news regarding the discovery of a new Indo-European language in Summer 2023 on a Cuneiform tablet at the Boğazköy-Hattusha archaeological site, the capital of the Hittites. The tablet contains an introduction stating that a ritual expert conjures in (the language) of Kalašma. What follows is a text that is not yet fully comprehended (but on which significant progress is made on a regular basis), written in a language sharing obvious similarities with the other Anatolian languages known so far but also exhibiting isolated features. During the Winter 2024 MASt seminar, Rieken presented the complete text and offered some hypotheses concerning its lexical and grammatical interpretation, which resulted from her collaboration with Dr. Ilya Yakubovich.

§5. While both papers were fully presented and extensively discussed at the live session of the Winter 2024 MASt seminar, the present MASt report only reports Meissner’s paper and following discussion due to copyright agreements.

§6. The MASt board wholeheartedly thank Elisabeth and Ilya for generously sharing images, contents, progress, and brand-new hypotheses during the Winter 2024 MASt seminar. We can hardly wait to read in full the stellar work there are producing!

§7. More than 100 attendees took part in the Winter 2024 MASt seminar. Substantial discussions followed both presentations, though we only report here the discussion following Meissner’s talk for the above-mentioned reasons. Specifically, contributions to Meissner’s talk were made by Daniel Kölligan (see below at §§ 53; 55; 57), Torsten Meissern (§§35–36; 40; 42; 44; 48; 50; 52; 54; 56; 58; 60), Gregory Nagy (§§33–34), Tom Palaima (§§38–39; 41; 43; 45; 49), Rachele Pierini (§59), Carlos Varias (§46), Brent Vine (§37), Roger Woodard (§§47; 51).

Topic 1. The Greek Nouns in -εύς : some further thoughts and recent developments

Presenter: Torsten Meissner

§8. It can be said without exaggeration that the nouns in -εύς are one of the most problematic and most controversially discussed group of nouns in the whole of Greek. This concerns both the formation itself and, in particular, their origin. Attested from Mycenaean onwards, in the most general terms, they are attested both as masculine personal names and as appellative nouns. In alphabetic Greek, most of the appellatives indicate men in their professions or social roles, such as βασιλεύς “king”, χαλκεύς “smith” < χαλκός “bronze”, ἱππεύς “horseman” < ἵππος “horse”, οἰκεύς “servant” < οἶκος “house”. Since they intrinsically indicate an activity, we also find, probably secondarily, proper agent nouns such as φονεύς “murderer” < φόνος “murder”. We also find a small number of instrument nouns such as ὀχεύς “holder”, cf. ἔχω “I hold”, or ἀμφιφορεύς “amphora”, lit. “carrier on both sides” < ἀμφί “on both sides” and φέρω “I carry”. It seems unproblematic to motivate this latter extension; the use of agent noun suffixes for instrument nouns is seen in other IE languages as well, e.g. in English -er, ultimately < Lat. -ārius primarily derives profession nouns such as teacher, painter and agent nouns like sender, listener, just like Greek -εύς, but also, less frequently, instrument nouns like cooker, freezer, carrier, the latter being ambiguous of course. It is important to note that almost all of these nouns are simple nouns in Homeric Greek;[1] there is a very small number of exceptions like ἀμφιφορεύς that will be considered further below (§17).

§9. There is one single noun in -εύς in Homer denoting a place: δονακεύς “thicket of reeds” < δόναξ “reed”, and again we will come back to this (§18). The total number of proper nouns, however, is not large in Homer: 23 appellatives in total are attested, and several of them are but attested once. Much more frequent are the personal names in -εύς: Homer has 62 different names of this type, most prominently of course the chief characters of the two epics, Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς and Ὀδυσ(σ)εύς respectively. Some of these names are speaking names and transparent inventions of Homer, such as the names of the Phaeacians like Ναυτεύς “Sea-Farer” (: ναύτης “sea-farer”), Ἐρετμεύς “Rower” (: ἐρετμόν “oar”), all semantically obviously close to the agent/profession nouns that we have already seen. But in their majority, the names are completely unclear such as Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς and Ὀδυσ(σ)εύς, Τυδεύς, Βρισεύς, Νιρεύς. To be sure, for the former two, and Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς in particular, there has been no shortage of attempts at finding an Indo-European etymology for them; but epigraphically attested variants such as ΟΛΥΤΤΕΥΣ, ΟΛΥΤΕΣ, ΟΛΙΣΣΕΥΣ, ΟΛΙΣΕΥΣ, ΟΛΥΣΕΥΣ, ΟΛΥΣΣΕΥΣ and of course Latin Ulixes hardly inspire confidence in such attempts; in my view, the most charitable thing that can be said about such attempts is that they are unprovable given that the words in questions are names. By necessity, therefore, the argumentation needs to concentrate on the appellative terms when it comes to evaluating the inner-Greek derivational patterns, restrictions and productivity. However, when considering the origin of the formations it seems methodologically unacceptable to me to ignore, dismiss and/or separate the onomastic evidence, implicitly or explicitly, from the appellative terms, or to claim that somehow non-Greek names were secondarily adapted to pre-existing Greek formations in -εύς,[2] especially in view of the fact that both in Homeric Greek and, as we shall see presently, in Mycenaean Greek, the personal names are substantially more numerous than the appellatives.

§10. In Mycenaean Greek, many more nouns in –eus are attested than in Homer, about 245 in total.[3] We find a plethora of personal names about 150, and indeed partly the same ones as in later Greek such as a-ki-re-u = Ἀχιλλεύς, and appellative words like qa-si-re-u /gu̯asileus/ ‘foreman’ or ‘local official’, corresponding formally, though not semantically, to later Greek βασιλεύς ‘leader’, after Homer generally ‘king’, i-je-re-u = ἱερεύς ‘priest’, ke-ra-me-u = κεραμεύς ‘potter’, ka-ke-u = χαλκεύς ‘smith’. But in Mycenaean Greek, the suffix is used much more widely. It can denote ethnics such as pe-di-je-we ‘people of the plain’ < πεδίον ‘plain’ or do-ri-je-we ‘Dorian’; it is also use liberally to form instrument nouns. A particularly instructive example is ke-ni-qe-te-we/kher-niku̯-tēwe(s)/ “hand wash basins”. In later Greek, the word is χέρνιβον, i.e. without a functional suffix. But in Mycenaean, in addition to the formation in -eus we also find a –t-; the most plausible explanation for this is that Mycenaean first had an extension with the ubiquitous instrument noun suffix –tro– as in e.g. ἄροτρον ‘plough’ (cf. Lat. aratrum), and this seems to have been extended secondarily with -eus, with a dissimilatory loss of the second r, i.e. *kher-niku̯-tr-eus > kher-niku̯-t-eus.[4]But in Mycenaean we also find a number of place names in –eus. Many of them are pl. e.g. a-pa-re-u-pi, formally an inst. pl. but clearly used as a locative. The most common and likely explanation for this is that these are in origin the names of the inhabitants which, used collectively, are equivalent to a place name, cf. apud Oxonienses = Oxonii “in Oxford”. A variant on this is the collective name for people in charge of a shrine, temple or other locality of a divinity, e.g. po-si-da-i-je-u-si “people in charge of the po-si-da-i-jo, i.e. the temple of Poseidon”.

§11. Clearly the most controversial aspect of these formations, however, concerns their origin. This question has been tackled many times over the last 170 years or so and there is absolutely no agreement. Almost all conceivable positions have been taken here:

- The suffix is inherited from PIE; this position is taken, e.g., by Schindler 1976, Hajnal 2005, de Vaan 2009, Olsen 2019. Though this view is not uncommon, it is worth pointing out that there is precious little agreement on the internal analysis and thus the precise origin of the suffix.

- The suffix was created in Greek based on inherited morphology (Santiago Álvarez 1987 and 2017, Szemerényi 1957; again, the details vary considerably).

- The suffix is borrowed from another, unattested ‘para-Greek’ IE language (Leukart 1994).

- The suffix is borrowed from an unknown, foreign language (Debrunner 1916, Risch 1974, Chantraine 1933, Boßhardt 1942).

- The suffix is partly inherited, partly borrowed (Beekes 2010).

§12. This is neither the place to discuss in detail the various suggestions, nor is there enough space to do so. I intend to do so in a monograph in preparation, however, and will only outline the principal problems with the various theories and suggestions.

§13. As to the claim that the formation is inherited, the main problem is that it has no clear parallel in any other IE language. The Lithuanian agent noun suffix -ius seems relatively close and has repeatedly been invoked as either a closely related formation (thus Schindler 1976) or as directly comparable (Olsen 2019). The former is tenuous because of the problems with Schindler’s assumption itself as will be explored in the next section,[5] the latter does not work without invoking several stages of reanalysis and remodelling; readers will make up their own minds as to whether they regard this as plausible. There certainly are no word equations between these two languages here.

§14. A few Phrygian words in -avos have also been adduced in order to argue for the suffix to be inherited: proitavos and akenanogavọṣ have both been taken to be the gen. sg. of papponyms, with -avos < *-ēu̯-os.[6] That proitavos should be anything like this, or indeed should be a gen. sg., is far from clear, however,[7] and even if it is a name it does not prove in any way that nouns in -eus were in any way integrated into Phrygian morphology – the name may have been borrowed from an unknown language into Phrygian in the same way that names in -eus may have been borrowed into the closely adjacent Greek language.[8] The meaning and formation of akenanogavọṣ are equally unclear; if it were a formation in -eus[9] then the length of the word suggests that it is a compound which is precisely not what Greek nouns in -εύς tend to be. In either case, the Phrygian evidence is inadequate to prove that the suffix was inherited from the parent language.

§15. Of the various attempts to reconstruct the suffix for PIE the one advanced by Jochem Schindler 1976 has proved to be the most influential. He assumes, amongst other things, that

- That the nouns in -eus are originally secondary derivatives from o-stem nouns, i.e. that we start from a pattern like ἵππος > ἱππεύς.

- That these o-stem nouns show the alternative form of the thematic vowel namely –e– here; this is seen in the declension of these nouns, in Latin dominus, voc. domine, same in Greek and many other IE languages, κύριος : κύριε, and that this form in –e– would have formed the basis for the derivation.

- The derivation then occurred with a suffix that in itself showed paradigmatic ablaut, *-u– : *-éu– or in prevocalic position *-éu̯-, the distribution being that *-u– appears in the ‘strong cases’ nom. and acc. where the word accent would be on the lexical root while in the weak cases (essentially the rest, with question marks regarding the locative) would have had the accent on the suffix which then displays the full form of the suffix, i.e. *-éu– or in prevocalic position *-éu̯-. This in itself is a pattern found elsewhere in PIE and not as such objectionable. This means that we would have had something like this as the original paradigm, staying with the PIE word for horse:

nom. *ék̑u̯e-u̯-s

gen. *ek̑u̯e-éu̯-os

The nom. would thus give us Gk -εύς straightaway, in the weak cases *-e-eu̯– would give us –ēu̯.

In the accusative, being a strong case, we would expect *ek̑u̯e-u̯-m. If the formation is old enough, i.e. of early PIE age, we would expect this to develop to *ek̑u̯ēm by Stang’s Law, whereby the *u̯ is probably assimilated to the *m, so that * -eum > *-emm > *-ēm with simplification of the double consonant and compensatory lengthening of the preceding vowel so as to maintain the syllable weight. This process is well known, of course, from two very old words, namely the word for sky and cow: *di̯eu̯s (or conceivably *di̯ēu̯s) > Skt. dyaus, acc. *di̯eu̯m > di̯ēm, Greek Ζῆν, Skt dyām; *gu̯ou̯s > βοῦς, Skt gaus, acc. * gu̯ou̯m > Greek βῶν “ox-hide shield”, but in Mycenaean Greek the w-less forms are still paradigmatic as shown by acc. pl. qo-o /gu̯ōns/, corresponding to Skt. gām. This could then conveniently explain the acc. forms in -ēn sometimes seen in Greek dialects, e.g. Arcadian hιερεν, and from this form a new nom. in *-ēs would have been created by analogy, resulting in forms parallel to o-stem –on : -os, or masc. ā-stem -ān : –ās.

The feminine would have been in *-ē̆u̯-i̯a and all that remains to claim then is that this had developed to *-eyya (later Greek -εῖα) already by the Mycenaean Greek period, in view of feminine formations like i-je-re-ja, ke-ra-me-ja.

§16. While this has some attractive points there are major difficulties with Schindler’s suggestion. The one I would like to focus on here is the derivational basis, i.e. the claim that nouns in *-eus were first derived from o-stems, not least because many later works accept this and build their argumentation on it. It is true that in Homer the majority of the appellatives are derived from o-stems but Leukart is clearly right in pointing out that no such pattern can be seen in Mycenaean where the picture is much more blurred.[10] While we do find such formations like i-je-re-u/i-e-re-u, ἱερεύς : i-je-ro, ἱερεύς or ka-ke-u χαλκεύς : ka-ko χαλκός, many nouns in -eus are formed from other bases in Mycenaean Greek, e.g. ko-to-ne-we “land-holders” (pl.) < ā-stem ko-to-na κτοίνα “parcel of land”; a-mo-te-wo“charioteer” (gen.) < mn̥(t)-stem a-mo, gen. a-mo-to, corresponding to later ἅρμα, ἅρματ-ος; ze-u-ke-u-si dat. pl. derived from the neuter s-stem noun found in Myc. in the dat. pl. ze-u-ke-si (and also in the acrophonic abbreviation ZE), later Gk. ζεῦγος “yoke, pair”; gen. me-ri-te-wo from the t-stem Myc. me-ri, gen. me-ri-to, later Gk. μέλι, μέλιτος “honey.”

§17. Mycenaean Greek, it would seem, does not allow to establish an original derivational basis but there clearly is no preponderance of derivatives from o-stem nouns. This is not convenient for Schindler who therefore claims that the Homeric situation is closer to the original, turning the chronology of attestations on its head. His reasoning is that if the formation had originally been limited to o-stems then it is easy to see how it could have spread to other stems while the converse is not true: why, if it had been a ubiquitous suffix, should it later on have been limited to o-stems which are so clearly in the majority in Homer as far as the basis for the derivation is concerned. What I wish to pursue here is the questions as to whether this is actually true, and if it is, whether it is decisive. Schindler himself says that in Homer there are only 8 attestations of nouns in -eus not derived from o-stems, and this is dwarfed by 176 attestations from o-stems. This may be true, but this concerns the total number of attestations, not different lexemes. If we take, as we should, this as the basis for our comparison, the figures look rather different: there are 23 different appellative lexemes in -eus, of which at best 5 are formed from non-o-stem nouns. The o-stems still form a considerable majority but in fact I think this list needs to be pruned further. We established at the beginning that the nouns in -eus in alphabetic Greek are essentially simple nouns. However, we do find in Homer 3 compounds: ἀμφιφορεύς, which is already attested in Mycenaean a-pi-po-re-we, ἡνιοχεύς “charioteer”, literally “rein-holder” and πατροφονεύς “father-murderer”. Or so the dictionaries would have it. A closer look reveals, however, that things are not so simple. ἡνιοχεύς is certainly remarkable. The original form is ἡνίοχος and this is also the form seen in Myc. a-ni-ọ-ko. ἡνιοχεύς as such does not even exist; what we find is nom. pl. ἡνιοχῆες (1x) and acc. sg. ἡνιοχῆα (3x), and all of these instances are found at the end of the line where the regular formation would not have scanned, filling a fixed metrical slot, namely the position following the bucolic diaeresis, i.e. they have the metrical shape ̶⏖ ̶x. The same is true for πατροφονεύς. Having the exact same metrical shape as the previous word, this is only attested in the acc.sg. πατροφονῆα (3x), and clearly a secondary extension of πατροφόνος, regularly formed and found from Aeschylus onwards. For sure, these words are derived from o-stems but are very clearly secondary formations[11] that cannot tell us anything about the original basis for the derivation. Forms in -ῆα, nom. pl. -ῆες and acc. pl. -ῆας can be formed from any base in Homer if the metre requires it, i.e. in verse-final position. Thus, from an ā-stem masc. name Ἀντιφάτης, lit. “Gain-sayer” or, possibly, “Reflector”, we find in Homer, alongside the regular forms Ἀντιφάτης, Ἀντιφάτην and “Aeolic” gen. Ἀντιφάταο, the remarkable acc. Ἀντιφατῆα in precisely this position where the regular acc. Ἀντιφάτην would not scan. As long as the word has the metrical shape ̶⏖ ̶x and the semantics are vaguely agentive, anything goes, and suddenly Homer and Mycenaean look much more alike. By way of contrast, the only compound that seems “real”, i.e. not a form created or indeed preserved metri gratia is ἀμφιφορεύς. This is confirmed not just by the existence of this word in Mycenaean but also, and saliently, by the fact that in Homer there is no metrical restriction as to the cases – the nom. sg. ἀμφιφορεύς is attested, as is the dat. pl. ἀμφιφορεῦσι, and there is likewise no restriction as to the metrical slot, the word occurs in all sorts of positions in the line in Homer.

§18. Words like πατροφονῆα, ἡνιοχῆα, -ες must thus be left out of consideration here. But the point is worth pushing further. Schindler also counts the noun φονεύς “murderer” as derived from an o-stem, namely φόνος“murder”. However, quite apart from the fact that φονεύς is a proper agent noun and as such probably secondary anyway,[12] this word is found no more than three times at best in the whole of Homer, and indeed only in verse-final position, and only the gen. φονῆος and the acc. pl. φονῆας:

Iliad 9.632 νηλής· καὶ μέν τίς τε κασιγνήτοιο φονῆος (v.l. φόνοιο)

Iliad 18.335 τεύχεα καὶ κεφαλήν, μεγαθύμου σoῖο φονῆος·

Odyssey 24.434 εἰ δὴ μὴ παίδων τε κασιγνήτων τε φονῆας

§19. In other words, this word only occurs in the exact same position as the secondary formation πατροφονῆα. The attestation in Il. 9.632, if genuine at all, and certainly παίδων τε κασιγνήτων τε φονῆας in Od. 24.434—a notoriously late book—“murderer of one’s children and siblings” very strongly evokes πατροφονῆα. I think there is a not inconsiderable chance that the simplex word φονεύς is secondarily derived from the verb φονεύω, meaning that the derivational chain was φόνος > φονεύω > φονεύς and that the creation of the latter was helped along by the existence of the compound πατροφονῆα. This seems to be the most plausible way to account for the positional restriction and the rarity of attestation found in Homer. Another case in point is φορεύς “carrier”. It is found once in Homer (Il. 18.566) and then disappears from the record altogether until the 3rd century BC when, tellingly, the epic poet Apollonius of Rhodes uses it again who in general draws very heavily on Homer. This word has all the hallmarks of purely epic creation, and it can hardly be derived from the o-stem noun φόρος as this means “tax, contribution”. Much rather, this word could be formed because ἀμφιφορεύς already existed, and was a real word. Other words like νομεύς “herdsman” are also suspicious, and the number of unequivocal derivations from o-stem nouns in Homer is in my view considerably smaller than Schindler makes out to be. Also, for some words, above all βασιλεύς, there is no derivational basis in sight in Greek at all. In addition, Schindler, as well as practically all others, completely disregard the personal names which, as we have seen, are nearly three times more frequent than the appellative words. Some of them are clearly speaking names, such as Ἐρετμεύς “Rower” which is derived from the o-stem ἐρετμόν “oar” but then again Ναυτεύς “Sea-Farer” is not but is a derivative from the ā-stem ναύτης. But very many of them like Νιρεύς, Βρισεύς do not have any derivational basis in Greek at all, let alone an o-stem. It was pointed out above (§9) that those scholars who claim a double origin of the Greek formations in -εύς[13] explicitly or implicitly separate the names from the appellatives which are not; apart from maybe βασιλεύς, βραβεύς and ἑρμηνεύς. I find this unsatisfactory. Personal names and names of professions often go hand in hand. We see this not just in the names of the Phaeacians in Homer but also, and in particular, with foreign titles or appellatives which are routinely misinterpreted by people who are not competent in the language to which these terms belong. Thus, in Homer, Πάλμυς is used as the name for one of the Trojan fighters (Il. 13.792) but it is of course based on the Anatolian word for “king” that in Lydian is qaλmλus. And in Mycenaean Greek personal names and names of professions are sometimes blurred: ka-ke-u indicates the profession “smith” but on PY Jn 750 it is used as or like a personal name and serves as the sole identifier of one person.

§20. The primacy of o-stems that Schindler claimed in order to legitimize his approach of taking the Homeric evidence as more original than the Mycenaean one, is really rather questionable and I think that we must start from the Mycenaean evidence when considering the origin of the formations in -eus.

§21. A very different approach was taken independently, and in different ways, by Santiago Álvarez first in 1973, then in more detail in 1987 and again in 2017, and by de Vaan 2009. The latter takes as his starting point the Anatolian word for horse. The standard reconstruction of this is *h1ek̑u̯o-s, in other words, an o-stem. But de Vaan notes that Kloekhorst argued that in Anatolian, the word is a u-stem, cf. Hittite ANS̆E.KUR.RA-us, Hieroglyphic Luwian asu- etc. all < *h1k̑ēu-.[14] The development to an o-stem would be a post-Anatolian PIE development. From this old form of the word, we would get a locative *h1k̑ēu “on the horse”. From this, a new lexeme would be derived: *h1k̑ēu-s “the one on the horse, horseman”, a form of hypostasis or internal derivation without suffixation. Now, a form *h1k̑ēu-swould in Greek perhaps have given **ἰκεύς so de Vaan has to argue that in the new word *h1k̑ēu-s “the stem form *h1k̑ēu- was reintroduced”, giving *h1k̑u̯ēus. A stem *h1k̑u- is not attested anywhere. De Vaan reconstructs it for the gen.sg. but it remains hypothetical. The reconstruction is thus tenuous and also uneconomical as it relies on analogy. Furthermore, this derivational type would then be extremely old which renders its non-existence outside Greek more of a mystery. This casts a clear shadow on what otherwise undoubtedly is a great merit of de Vaan’s reconstruction, namely the fact that he establishes an actual and direct link between nouns in *-u- and those in *-eu̯-, a link that otherwise is sorely missing.[15]

§22. Santiago Álvarez, on the other hand, begins by observing that in Mycenaean we find a considerable number of likely toponyms in -eus (as already mentioned §10).[16] Such formations also exist in later Greek but are rare. In Homer, we have seen the word δονακεύς “thicket of reed” and later on we find words and names like Πειραιεύς “Piraeus”, the port of Athens, ἐλαιεύς “olive grove” and φελλεύς “stony ground, poor quality land”[17] < φελλός“cork-oak”. The latter two clearly go particularly well with δονακεύς which is a derivative from δόναξ “reed”.[18] In Mycenaean, Santiago Álvarez further notes, we sometimes find a form in -e-u where from a syntactic point of view we would expect a locative (i.e. a form in -e-wi or -e-we), e.g. PY Jn 320.1 o-re-mo-a-ke-re-u,[19] and on other tablets belonging to the same series in the same position, in other words in the slot where we would expect to find a place name we do indeed get one, and in a form that is morphologically interpretable as a dative/locative, e.g. a-ka-si-jo-ne Jn 389.1. According to Santiago Álvarez, these are actually morphological locatives themselves, and she explicitly points to Sanskrit where locative of u-stem nouns such as sunús “son” is, after all, sunaú which can go back to *-ēu. The Mycenaean forms in em>-e-u in locatival function are consequently interpreted by Santiago Álvarez as actual archaic locatives in -ēu. These then would provide the starting point for the entire declensional type, i.e. a new paradigm is built on the locative forms. This is different from de Vaan’s approach since this would a) have happened within Greek and b) it does not involve the creation of a new lexeme, i.e. no derivational process but just the creation of a new declensional paradigm. This then means that there is an important difference between the Greek and Sanskrit forms as the Greek forms stems in –eu-. There are two issues that need to be examined here: a) Do the forms in -e-u actually point to locatives in -ēu? b) Can we see in them the starting point for the stems in -eus?

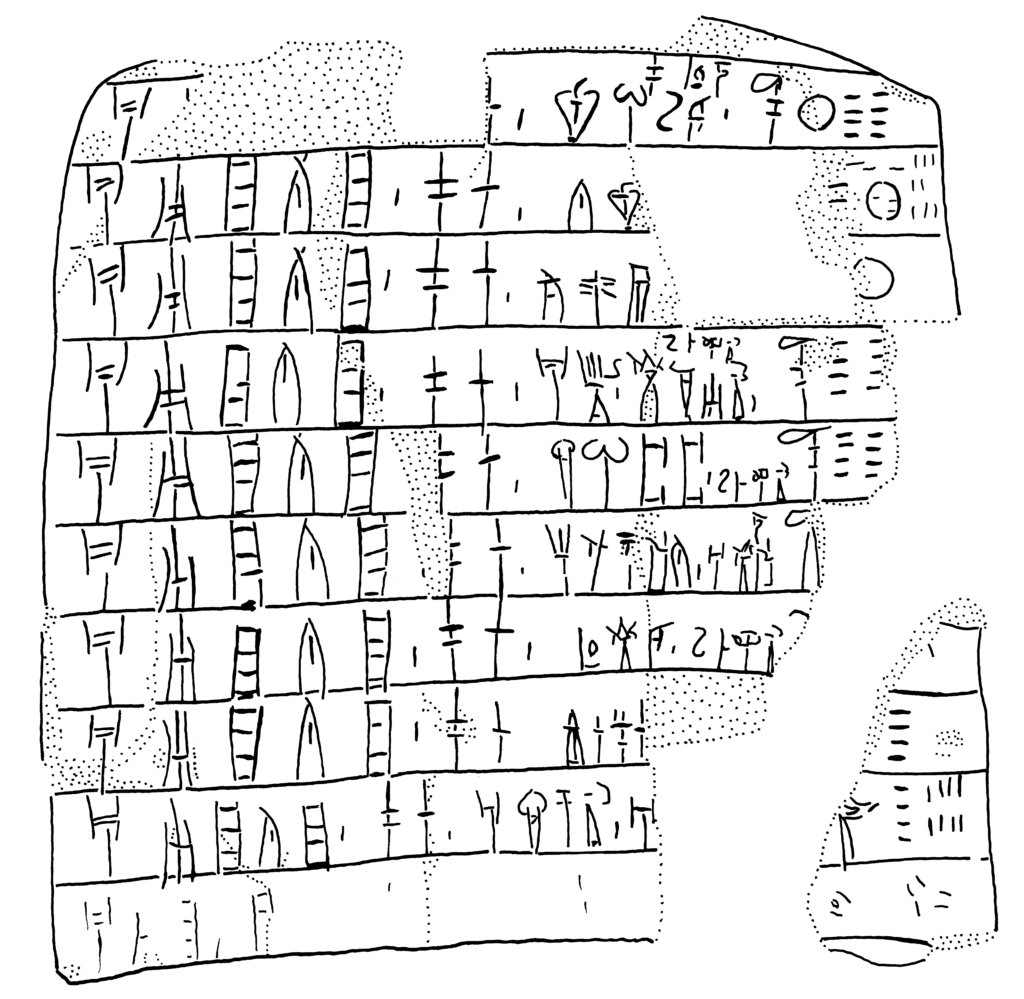

§23. Locative forms in -e-u are very rare, Santiago Álvarez lists a maximum of 11 forms in total. The most obvious problem here is the so-called nominative of rubric, i.e. the frequent replacement of the syntactically expected case with the nominative which doubtless is a frequent phenomenon.[20] Much of the evidence adduced by Santiago Álvarez can be explained in this way. However, there are two pieces of evidence that seem rather strong, at least at first sight. The first one is PY Cn 254:

.1a pa-ra-jo

.1b a-si[-ja-ti-ja pa-]ṛọ , tu-ru-we-u , OVISm 180

.2 a-si-ja-ti-ja , pa-ro , ti-tu[ ]ỌṾỊṢṃ 100

.3 a-si-ja-ti-ja , pa-ro , e-te-wa[ OVISx] 100

.4a we-da-ne-wo

.4b a-si-ja-ti-ja ,̣ pa-ro , a-no , de-ki-si-wo , OVISm 80[

.5 a-si-ja-ti-ja⌞ ⌟pa-ro , ko-ru-ta-ta , we-da-ne-wo OVISm 80[

.6a -jo

.6b a-si-ja-ti-ja⌞ ⌟pa-ro , i-sa-na-o-ti , a-ke-o- OVISf[ qs

.7 a-si-ja-ti-ja , pa-ro , ra-ke-u , we-da-ne-wo C̣ẠP̣x[ qs ] vacat

.8 a-si-ja-ti-ja , pa-ro , pi-ro-qo-ṛọ[ ] 40

.9 a-si-ja-ti-ja , pa-ro , a-ko-to-wo , a[ ]SUSf 48

.10 ⟦a-si-ja-ti-ja pa-ro ⟧[ ]⟦ SUSx ⟧

§24. Here, uniquely, we seem to be getting a locative in -e-u following a preposition, pa-]ṛọ , tu-ru-we-u in line .1b and pa-ro , ra-ke-u. It is furthermore remarkable that we find the forms in -e-u here not with toponyms but with personal names. The latter may give one pause. For a formation that, if it existed at all, must have been archaic even in Mycenaean times and that one might expect to survive in toponyms to be used with personal names and dependent on a preposition would seem to be rather surprising. But even if we allow for this, there are very good reasons to be skeptical.

§25. It was Nicole Maurice who first argued that these two names are actually in the nominative, despite the fact that they follow the preposition pa-ro: “En effet, la ligne 10, dont le texte a été raturé, révèle la manière dont le scribe a procédé pour rédiger la tablette: il a dû, dans la première phase de son travail, préparer dix débuts de lignes “asijatija , paro” pour n’avoir plus, ensuite, qu’à les compléter avec le nom du berger […]. Le nominatif de rubrique peut donc se recontrer, accidentellement, dans de tels conditions, en concurrence avec le datif-locatif.”[21]

§26. I think that this is completely right and that an even stronger argument comes from a look at the complete palaeography of the tablet:

Figure 1a. PY Cn 254 (photo) reproduced with kind permission of Louis Godart.

Figure 1b. PY Cn 254 (drawing) reproduced with kind permission of Louis Godart.

§27. The writing is regular and confident in every line (except the last one) until about the middle of the tablet. The remainder is written in characters that are clearly smaller, the signs closer together and, judging from the 2-dimensional photograph, incised less deeply. The last word written in the larger type is the preposition pa-ro. It really looks as though the entire tablet was pre-prepared and inscribed up to that point. The remaining information, i.e. the actual names and the signs for the various animals and their number were added later, after that information had been gathered. The scribe, or indeed a different scribe, thus returned to the tablet to complete it, quite possibly transferring information from smaller palm-leaf tablets. Given that all 9 or 10 entries on this list refer to the same place, a-si-ja-ti-ja, the palm leaf tablets may have contained only the personal name, the ideogram for the animal in question and the relevant number. Here, the personal names would naturally have been in the nominative, and when it came to completing the consolidated record, these names were simply transferred as they were.

§28. I should also like to point out that i-sa-na-o-ti in line .6 does not weaken the case. It is often taken as a dative but in fact the name is a hapax and may well be in the nominative, and comparable to a name like i-pa-sa-na-ti/e-pa-sa-na-ti on the PY E tablets; it might even be the same name. Finally, it is worth mentioning that case use is not at all consistent in the Cn series; cf. e.g. Cn 655 where unambiguous nominative forms like o-pe-re-ta, a-ta-ma-ne-u contrast with clear genitive forms like qe-re-wa-o, ke-ro-wo-jo, ra-pa-sa-ko-jo etc.

§29. The second piece of evidence is a cause célèbre, TH Ft 140:

.1 te-qa-i GRA+PE 38 OLIV 44

.2 e-u-te-re-u GRA 14 OLIV 87

.3 ku-te-we-so GRA 20 OLIV 43

.4 o-ke-u-ri-jo GRA 3 T 5

.5 e-re-o-ni GRA 12 T 7 OLIV 20

.6 vacat

.7 vacat

.8 to-ṣọ-pa GRA 88 OLIV 194

.9 vacat

§30. Here, we get a list of toponyms, and where the case form can be determined, it is in the locative te-qa-i line .1, the name of Thebes itself, and e-re-o-ni in line .5, clearly the locative of the town that in the Iliad is Ἐλεών. This might lead one to the conclusion that e-u-te-re-u in line .2 is also a locative. But again, it could be a nominative of rubric and is indeed so analyzed by Duhoux (2024: 631). Palaeographically, the tablet is remarkable as the final -u and the following ideogram seem to overlap. However, the reading seems clear, and e-u-te-re-u thus is real, but it seems difficult to square this form with the historical Boeotian Εὔτρησις. In order to build a bridge between Mycenaean e-u-te-re-u and later Greek Εὔτρησις, two suggestions have been put forward. Plath has argued that e-u-te-re-u is a mistake for e-u-te-re-se[22] which, in principle, is an attractive proposal. Watkins noted that the non-assibilated form is actually attested in later Boeotian Greek: ΤΕΥΤΡΕΤΙΦΑΝΤΟ on the famous “cantharus Mogeae”, IG 7.3467 = CEG 446, and we also find ΕΥΤΡΕΙΤΙΔΕΙΕΣ in a dedication to Apollo (IThesp 224) and he wants to correct e-u-te-re-u to e-u-te-re-te-u and explain this as “reverse dittography” of the locative of the non-assibilated i-stem Eutrētis.[23] This is ingenious but, quite apart from having to admit an error on the part of the scribe, having to assume the non-assibilated form for Mycenaean Greek is difficult; as is the assumption of a loc. sg. ending *-ēu for an i-stem in Greek.[24]However, the non-assibilated form in later Greek does show that this place name must have entered the Greek language, in whatever way, before the *ti > si in the East Greek dialects. What room this leaves for e-u-te-re-u must remain open. In any event, e-u-te-re-u is much better taken as a nominative, and perhaps the place is not identical with later Greek Εὔτρησις.[25]

§31. There are thus good reasons to reject the assumption of locatives in -e-u in Mycenaean Greek. But if at least some of them are genuine, would they help us explain the stems in -eus? Santiago Álvarez claims that there might be direct evidence:[26] In KN Vs 653 we find a personal name ra-ku and, according to her, this could be the same name as the “locative” ra-ke-u in PY Cn 254; this, then, would be the origin of the entire inflectional type which would have arisen within Greek but on the basis of inherited morphology. This is highly problematic. We have already seen that there is no good reason to take ra-ke-u as a locative and it must be very questionable whether the Pylian and the Knossian forms actually render the same name. ra-ku in KN Vs 653 very much looks like a Minoan personal name, just like the other names on that tablet, *49-sa-ro, ku-ka-ro[ and ra-te-me. Most problematic of all, however, is the fact that Minoan names ending in -u when adapted into Greek either retain their stem class or become o-stems as one might expect, e.g. LA qa-qa-ru, ku-*56-nu, a-ti-ru > LB qa-qa-ro, ka-*56-no, a-ti-ro respectively, and the same is true for the Minoan word for wool, written MA+RU which in Greek becomes μαλλός. The fact remains that there still is no obvious nexus between stems in -us and stems in -eus.

§32. A brief word, finally, on the view that the entire type is borrowed. An argument in favor here is the complete lack of a derivational basis for some salient words like βασιλεύς, βραβεύς and of course for countless PN such as Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς, Ὀδυσ(σ)εύς, Τυδεύς, Βρισεύς, Νιρεύς etc. (though for the first two of these, many etymologies have been proposed). Yet, what gives one pause is the fact that the formations are so very numerous in particular in the earliest period of the language, and they seem very well established and completely integrated into Greek morphology; not only this, we also find many denominative verbs in -εύω, and already in Homer these are not only vastly more numerous than the nouns in -εύς but also no longer in any way dependent on them: ἡγεμονεύω “Ι lead” is formed from ἡγεμών “leader”), ἀγορεύω “I speak in an assembly” from ἀγορά “assembly” etc.[27], and incidentally there is also ἡνιοχεύω (: ἡνίοχος) which may have helped to legitimize the outrageous ἡνιοχῆα that we saw earlier. And then there is of course the methodological issue – a borrowing from an unknown language is in a way the “last refuge of the scoundrel”, and with regard to the nouns in -εύς, this approach was castigated by Paul Kretschmer nearly 90 years ago: “Der Fall ist typisch: man glaubt eine griechische Spracherscheinung nicht aus dem Indogermanischen erklären zu können und schreibt sie ohne weiteres dem Vorgriechischen zu, dem großen Unbekannten; man kann es zwar nicht beweisen, aber man denkt, daß man auch nicht widerlegt werden kann.”[28] His words are as true now as they were then, and, for the moment at least, the nouns in -εύς jealously keep their secret.

Discussion following Meissner’s presentation

§33. Gregory Nagy thanked Meissner for his presentation and kicked off the discussion by commending Meissner for his attentiveness in transcribing Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς with the second λ in parentheses, representing two variant forms used for metrical purposes in Homeric texts—a topic that Nagy extensively discusses in his 2022 paper “Comments on Nick Allen’s thinking about myth and epic, Part II: On the dyadism of Achilles and Odysseus in the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey”

§34. Further, Nagy drew attention to an article by Gregory R. Crane (Crane 2022), in which he argues that Ἀχιλλεύς and Ὀδυσσεύς behave as a formula in Homer and are in fact metrically identical. Thus, Ὀδυσσεύς should also be written Ὀδυσ(σ)εύς, parallel to Ἀχιλ(λ)εύς. Nagy suggested that the peculiar behavior of these two -ευς-stems, which is perfectly consistent throughout both the Iliad and the Odyssey, could be further investigated and possibly enlightening to Meissner’s enquiries.

§35. Torsten Meissner agreed with Nagy, and further pointed out the great epigraphic variance found within the -ευς-stems in Homer in general, in relation to the work which is yet to be done on this topic.

§36. Meissner continued the discussion by bringing up the palaeography of TH Ft 140 and welcoming the audience to share thoughts on the interpretation of the final -u in e-u-te-re-u (line .2). Traditionally analyzed as a nominative of rubric, Meissner discussed in his talk the alternative reading -ēu, originally advanced by Santiago Alvarez, which would be indicative of a locative form.

§37. Building on this, Brent Vine added on the analysis, which Meissner mentioned with skepticism, of e-u-te-re-uby Calvert Watkins (2007). Watkins proposed a reading e-u-te-re-<te->u (locative, cf. Hom. Ἔυτρησις), with a syllabic sign missing due to reverse dittography, Vine highlighted.

§38. Tom Palaima stated that he would agree with the analysis of Melena in this case, and argues that the last sign is most likely an -u. Palaima also drew attention to the tablet PY Cn 245 and praised Meissner’s observation, as presented in the talk, that the left half of the line look like a template for the right half, possibly suggesting that they were filled in at a later date.

§39. Palaima added that, by looking at the RTI scan of PY Cn 245, he could see tu-ru-we-u and ra-ke-u at the bottom. He then highlighted that the nominative of rubric is a recurring feature in these tablets. Keeping in mind Chadwick’s distinction between oral and aural, it is important to try and imagine the conditions under which the scribes were receiving information, Palaima added. There would be times when the scribe would then go back and fix the syntax, but, on other occasions, he would be receiving the information and then just lapse and put down a so-called ‘nominative of rubric’ just to fill in the information, Palaima concluded.

§40. Meissner fully agreed and noted that this is especially likely if the scribe is working on dictation, that is in aural form.

§41. Palaima agreed and added that, in order to understand the aural process, we need to develop empathy and sympathy for these scribes, so that we can put ourselves in their situation and try to understand how they worked. Understanding how the information came to them is absolutely crucial, Palaima remarked.

§42. On Palaima’s request, Meissner shared again the image of TH Ft 140, and added that the enlarged portion of the tablet, corresponding to the bottom-left part, is quite poorly written. The sequence looks like e-u-te-re-u, but it is very hard to make sense of the text, Meissner continued. Meissner agreed with Palaima’s analysis and stated that his earlier interpretation of the last sign as -se no longer seems plausible.

§43. Palaima noted that it looks as if the sign for -u is being squeezed in. In his opinion, it looks as if the scribe was making a desperate effort to keep a stoichēdon format, that is to keep the ideogram GRA as carefully in line with its equivalents in the other lines as possible. He added that this forces him to squeeze the sign for u up against the ideogram in a way that causes the distortion—and this is all compounded by the break in the tablet, which is slightly crushed at the bottom part. Palaima wondered whether this might have something to do with the handling of the tablet, as it is possible to see some whorls on the tablet surface. According to Palaima, then, the reading –u- is accurate: the sign is simply jammed up against the ideogram for GRA.

§44. Meissner, with regards to the -u in TH Ft 140, agreed with Palaima, and further pointed out that the scribe possibly even wrote the ideogram down first and subsequently had to squeeze the preceding word to make it fit in the space left.

§45. Palaima found this solution possible but added that it would be necessary to look at an RTI scan to understand the situation better. He also remarked that he will keep looking at the tablet and thanked Meissner again for an excellent presentation.

§46. Carlos Varias mentioned Melena’s interpretation of o-ke-u-ri-jo (in line 4) as scriptio continua of o-ke-u and ri-jo /Orke:u Rhioi/ ‘at the Peak Orkeus’, with o-ke-u being interpreted as a locative in -e-u (Melena 2001:49). In Melena’s in fieri edition of Pylos tablets, the critical apparatus of the tablet recording o-ke-u-ri-jo reads “.4 read o-ke-u ri-jo?”, Varias concluded.

§47. Roger Woodard thanked Meissner for the fantastic presentation and asked how far in advance a scribe would need to pre-populate a clay tablet with symbols before the clay gets too hard to be worked on again.

§48. Meissner explained that the scribe might have had to soften again the right-hand side. He then went on to explain that some experiments have been conducted in order to determine for how long it is possible to work on a clay tablet before the clay gets too hard; from these experiments, it was ascertained that, depending on storage method and location, it is possible to keep working on the tablet for up to 24 hours.

§49. Palaima added that, if a scribe had started inscribing a tablet and received new information some hours later, he would have been able to write it down with the tablet still being fairly moist. This, of course, would also depend on the weather conditions of that day, Palaima highlighted.

§50. Meissner concluded by adding that, even without modern artifacts such as zip-lock bags, it is still possible to keep the clay moist for a reasonable amount of time.

§51. Woodard went on to ask Meissner what his stance is on the so-called “borrowing explanation” of the -ευς form.

§52. Meissner replied that, although in the past he has been more sympathetic to it, he is now a bit more skeptical—the “borrowing explanation” is, in a way, “the last refuge of the scoundrel”. If indeed the form is inherited, Meissner observed, where is this form in other languages? If, on the other hand, the form has been created from within the Greek language, it is very difficult to see the nexus between inherited u-stems and the stems in -eu-, Meissner added. If the suffix is borrowed, it would be very tempting to see Minoan as the language from which the form comes, Meissner remarked. However, there are no names in -e-u in the Linear A record and, therefore, for the time being, the question has to remain open, Meissner concluded.

§53. Daniel Kölligan asked about forms like χαλκεύς or κεραμεὐς—these first words that seem to occur and are apparently not based on Indo-European roots.

§54. Meissner interjected by saying that these forms seem to be ubiquitous from their first attestations, meaning that it is not proven that these words lie at the bottom of the formations in -eus.

§55. Kölligan continued by highlighting that productivity in itself is not an argument for or against borrowing, so it might not be a decisive point for this specific question.

§56. Meissner agreed and added that, as it stands, it still seems very hard to identify the starting point of the formation from a morphological point of view.

§57. Kölligan agreed that the question remains open. He then brought the example of Latin forms in -arius, which were borrowed into German as agent nouns (Meissner had already referred to the agent nouns in -er in his talk); the process started with professional names, such as piscarius (‘fisher’).

§58. The parallel is tempting, but of course it is impossible to prove that a similar process occurred in Mycenaean, Meissner noted.

§59. Pierini thanked Meissner again for the great presentation and wished to close the section on a personal note by asking Meissner to say a few words on Anthony Snodgrass, a very dear friend of the MASt seminars and whose Festschrift hosts a paper by Meissner with his preliminary thoughts on the Greek forms in -ευς (Meissner 2017).

§60. Meissner shared that, when he arrived in Cambridge, Anthony Snodgrass was professor of archaeology. Meissner added that he has always admired him and his work, and in particular the fact that he was not only looking at archaeological questions, but also at epigraphical and linguistic aspects. Meissner reflected that he learnt the most from him and John Killen and informed the audience that the volume of The New Documents of Mycenaean Greek, edited by John Killen, is now out and available on the Cambridge University website.

§61. Bibliography

Beekes, R. 2010. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. Leiden and Boston.

Boßhardt, E. 1942. Die Nomina auf -ευς. Ein Beitrag zur Wortbildung der griechischen Sprache. Zürich.

CEG = Hansen, P. A. 1983. Carmina Epigraphica Graeca Saeculorum VIII-V a. Chr. n. Berlin.

Chantraine, P. 1933. La formation des noms en grec ancien. Paris.

Crane, G. R. 2022. “Achilles and Odysseus, formulaic counterparts of Tweedle-Dee and Tweedle-Dum.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/achilles-and-odysseus-formulaic-counterparts-of-tweedle-dee-and-tweedle-dum/.

Duhoux, Y. 2024. “Land Tenure.” In The New Documents in Mycenean Greek, vol II (Selected Tablets and Endmatter), ed. J. T. Killen, 565–632. Cambridge.

Debrunner, A. 1916. “Review of E. Boisacq, Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque.” Göttingische gelehrte Anzeigen 178: 737–742.

Hajnal, I. 2005. “Das Frühgriechische zwischen Balkan und Ägäis: Einheit oder Vielfalt?”. In Sprachkontakt und Sprachwandel: Akten der XI. Fachtagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft, 17. bis 23. September 2000, Halle an der Saale, ed. G. Meiser, and O. Hackstein, 185–214. Wiesbaden.

IThesp = Roesch, P. 2007. Les inscriptions de Thespies V. Lyon.

Jiménez Delgado, J. M. 2018. “Nominative Case and Brachylogic Syntax in Mycenaean Greek”. Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici N.S. 4: 75–94.

Killen, J. T. 2024. “Mycenaean Glossary”. In The New Documents in Mycenean Greek, vol II (Selected Tablets and Endmatter), ed. J. T. Killen, 921–1056. Cambridge.

Killen, J. T., ed. 2024. The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek, vol. I-II. Cambridge.

Kloekhorst, A. 2008. Etymological Dictionary of the Hittite Inherited Lexicon. Leiden and Boston.

Krasilnikoff, J. A. 2008. “Attic φελλεύϛ. Some Observations on Marginal Land and Rural Strategies in the Classical Period.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 167: 37–49.

Kretschmer, P. 1935–1936. “Literaturbericht für das Jahr 1933”. Glotta 24: 56–95.

Kuiper, F. B. J. 1942. “Notes on Vedic noun-inflexion”. Mededelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie van Wetenschappen 5(4): 161–256.

Leukart, A. 1983. “Götter, Feste und Gefäße. Mykenisch -eus und -ēwios: Strukturen eines Wortfeldes und sein Weiterleben im späteren Griechisch”. In Res Mycenaeae: Akten des VII. Internationalen mykenologischen Colloquiums in Nürnberg vom 6.-10. April 1981, ed. A. Heubeck, and G. Neumann, 234–252. Göttingen.

Leukart, A. 1994. Die frühgriechischen Nomina auf -tās und -ās: Untersuchungen zu ihrer Herkunft und Ausbreitung (unter Vergleich mit den Nomina auf -eús). Vienna.

Ligorio, O. and A. Lubotsky. 2018. “Phrygian”. In Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics, ed. J. Klein, B. Joseph, and M. Fritz, 1816–1831. Berlin and Boston.

Maurice, N. 1987. “Existe-t-il des locatifs singuliers en -eu en grec mycénien?” LALIES Actes des sessions de linguistique et de littérature 5: 65–74.

Meissner, T. 2017. “Archaeology and the archaeology of the Greek language. On the origin of the Greek nouns in -εύς.” In The Archaeology of Greece and Rome. Studies in Honour of Anthony Snodgrass, ed. J. Bintliff, and N. K. Rutter. Edinburgh.

Meister, K. 1921. Die homerische Kunstsprache. Leipzig.

Melena, J. L. 2001. Textos griegos micénicos comentados. Vitoria.

Obrador-Cursach, B. 2020a. The Phrygian Language. Leiden and Boston.

Obrador-Cursach, B. 2020b. “On the Place of Phrygian among the Indo-European Languages”. Journal of Language Relationship 17: 233–245.

Olsen, B. A. 2019. “Indo-European syntax in disguise: the Greek type ἱππεύς and related formations”. Indogermanische Forschungen 124: 279–304.

Plath, R. 2014. “Mykenisch e-u-te-re-u und der Lokativ Singular der i-Stämme im spätbronzezeitlichen Griechisch”. In Das Nomen im Indogermanischen. Morphologie, Substantiv versus Adjektiv, Kollektivum. Akten der Arbeitstagung der Indogermanischen Gesellschaft vom 14. bis 16. September 2011 in Erlangen, ed. N. Oettinger, and Th. Steer, 307–317. Wiesbaden.

Risch, E. 1974. Wortbildung der homerischen Sprache. Zweite, völlig überarbeitete Auflage. Berlin and New York.

Santiago Álvarez, R.-A. 1973. “Mycenaean Locatives in …e-u”. Minos 14: 110–122.

Santiago Álvarez, R.-A. 1987. Nombres en -εύς y nombres en -υς, -υ en micénico: Contribución al estudio del origen del sufijo -εύς. Bellaterra.

Santiago Álvarez, R.A. 2017. “De nuevo sobre los nombres en -eus en micénico”. In Miscellanea Indogermanica. Festschrift für José Luis García Ramón zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. I. Hajnal, D. Kölligan, and K. Zipser, 745–757. Innsbruck.

Schindler, J. 1976. “On the Greek type ἱππεύς”. In Studies in Greek, Italic and Indo-European Linguistics offered to L. R. Palmer, ed. A. Morpurgo Davies, and W. Meid, 349–352. Innsbruck.

Szemerényi, O. 1957. “The Greek Nouns in -εύς”. In ΜΝΗΜΗΣ ΧΑΡΙΝ, Gedenkschrift Paul Kretschmer, vol II, ed. H. Kronasser, 159–181. Vienna.

de Vaan, M. 2009. “The derivational history of Greek hippos and hippeús.”Journal of Indo-European Studies 37: 198–213.

Watkins, C. 2007. “Mycenaean e-u-te-re-u TH Ft 140.2 and the Suffixless Locative.” In Verba Docenti. Studies in Historical and Indo-European Linguistics Presented to Jay H. Jasanoff by Students, Colleagues, and Friends, ed. A. J. Nussbaum, 359–363. Ann Arbor and New York.

Final remarks

§62. Rachele Pierini thanked the speakers for their outstanding papers and the audience for engaging in lively debates and offering insightful observations. She extended an invitation to all to participate in the upcoming Spring 2024 MASt Seminar, featuring speakers Artemis Karnava and Nicoletta Momigliano.

[1] See Risch 1974: 157.

[2] As done, e.g., by Olsen 2019: 281–282.

[3] The exact number is difficult to determine in view of the graphic ambiguities of Linear B and the sometimes fragmentary documentation. For an overview and detailed treatment of the Mycenaean formations in -e-u see, in the first instance, Santiago Álvarez 1987 and also Leukart 1994: 240–262.

[4] Thus Leukart 1994: 244. However, Mycenaean Greek attests to a certain number of formations in -te-u such as au-ke-i-ja-te-we, e-ni-pa-te-we, te-wa-te-u, tu-ra-te-u, to-wa-te-u, po-qa-te-u. None of these formations is particularly clear but tu-ra-te-uand po-qa-te-u probably are occupational terms (Killen 2024: 1012: “Probably a title: poss. phoigwasteus ‘purifier’ or ‘prophet’? [Cf. φοιβάζω]”). It is thus equally conceivable that Mycenaean had a ready-made suffix –teus (extension with -eu- of agent nouns in –tā-, cf. Hom. PN Ναυτεύς vs. appell. ναύτης? ) that could be used both for agent and instrument nouns. Either way, with the exception of γραπτεύς (= γραφεύς) found in Σ Ar. Th. 1103, this type of formation is unknown in later Greek.

[5] See Hajnal 2005: 200 for a brief but effective criticism and see also further below in §11.

[6] Thus Hajnal 2005: 200–201.

[7] See Obrador-Cursach 2020a: 86–88 for a sound analysis of these forms.

[8] Alternatively, it could be the case that the suffix was borrowed at an earlier, Graeco-Phrygian stage which is now commonly, and with good reason, assumed, cf. Ligorio and Lubotsky 2018: 1816 and Obrador-Cursach 2020b: 238–243.

[9] Advocated most recently by Obrador-Cursach 2020a: 87–88.

[10] Leukart 1983: 234; see also Hajnal 2005: 200.

[11] As first recognized and lucidly analyzed by Meister 1921: 173–174 who counts these formations among the “archaistische Kunstgebilde”.

[12] Cf. Risch 1974: 157.

[13] Such as Beekes 2010: xl or Olsen 2019: 281–282.

[14] See Kloekhorst 2008: 239.

[15] Kuiper 1942: 37, 47–49, and more recently Hajnal 2005: 202 have argued that Greek νέκῡς “dead body” with its long suffix vowel is a replacement for an older *νεκεύς (< PIE *nek̑ēu̯s) and that this is to be compared to Avestan acc. nasāum “dead body”. Why such a replacement should have occurred in the one language that maintained (in their view) the formations in *-eus remains entirely unclear. What does seem clear, on the other hand, is that the υ in Greek was originally short, see Beekes 2010: 1004 s.v. νεκρός; a lengthening would have occurred regularly and secondarily in the acc. pl. νέκῡς < *νέκυνς (in Homer attested alongside the more recent form νέκυας). From there it probably spread from there throughout the paradigm, resulting in the same oscillation between short and long υ in the paradigm as seen in ἰχθῦς/ἰχθύς “fish”. Furthermore, from a semantic point of view there is nothing that would link a putative *nek̑ēu̯s with the Greek nouns in -εύς.

[16] Santiago Álvarez 1987: 11.

[17] See Krasilnikoff 2008 for the precise meaning of φελλεύς.

[18] The Mycenaean place names in –eus may, in fact, differ subtly from these later ones. While, as seen, the former are often attested in the plural, the latter often have plant names as their base (ἐλαία, φελλός, δόναξ; for Πειραιεύς cf. Hom. acc.sg. πείρινθα ‘wicker basket?) and the formation may be close to that of an agent noun, e.g. φελλεύς may have to be understood as “the place that brings forth cork oak”, the “cork oak maker”.

[19] Santiago Álvarez 1987: 11.

[20] See Jiménez Delgado 2018 for a recent, in-depth exposé and analysis of the nominative of rubric in Mycenaean.

[21] Maurice 1987: 71.

[22] Plath 2014: 315.

[23] Watkins 2007: 362.

[24] See Plath 2014: 310–315 for a detailed criticism.

[25] Without wishing to put too much emphasis on this, it should also be noted that the syllabograms u and we sometimes seem interchangeable inasmuch as we is occasionally written where we might expect u, e.g. we-je-we “shoots” vs. later Greek υἱήν· τὴνἄμπελον Hsch., we-a2-re-jo vs. ὕαλος, we-e-wi-ja vs. ὕειος.

[26] Santiago Álvarez 1987: 24.

[27] See Risch 1974: 332–335 for details.

[28] Kretschmer 1935–1936: 84.