2. What do Linear B tablets tell us about Mycenaean diplomatic relations? A comparison between Mycenaean and Hittite Documents recording vessels and furniture

Presenter: Lavinia Giorgi

MASt Summer Seminar 2024 Report, Friday, June 28

Bronze Age Intergenerational Dialogues (BA.ID), 2:

Early Career Researchers (ECRs) at MASt,

https://doi.org/10.71160/QLGX4215

Introduction

§50. Diplomatic relations during the Late Bronze Age (LBA) in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean are documented by written, iconographical, and archaeological sources. For example, the royal correspondence testifies to political contact accompanied by gift-exchange (Mauss 1925; Liverani 1994:217—260; Liverani 1999:324—331; Zaccagnini 1999:181; Feldman 2006:14—18; Walsh 2016:54—55), such as the Amarna Letters and the Hittite diplomatic texts (Moran 1992; Liverani 1998; Liverani 1999; Beckman et al. 2011; Rainey 2015). Egyptian tomb paintings show diplomatic ceremonies and prestige objects, which are sometimes similar to gifts mentioned in the texts and the artifacts also present in archaeological contexts (Feldman 2006:16—18, 22, 29; Walsh 2014:202; Walsh 2016:58—61). These artifacts can be interpreted in two ways, either as the result of gift-exchanges between elites, in accompaniment with political relations, such as, the faience plaques and scarabs with the cartouche of the pharaoh Amenhotep III and his wife Tiyi found in Mycenae and Crete (Cline 1987; Cline 1993:22—34; Cline 1994). Alternatively, they might have been produced locally, consistent with a hybrid style shared throughout the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean, which scholars have called “International Style” or “International koine” (Feldman 2006:1—71 with quoted bibliography).

§51. Archaeological evidence shows that the Aegean communities participated in the LBA Near Eastern network (illustrative but not exhaustive bibliography in Cline 1993). However, written sources do not explicitly testify to diplomatic and political relations between the Mycenaeans and other contemporary rulers. The Amarna Letters, for example, do not mention the Mycenaeans among the pharaoh’s partners (Feldman 2006:9), and Linear B tablets are silent about any diplomatic relationship (Snodgrass 1991:16; Olivier 1997:277; Jasink 2005:60, 67; Kelder 2012:48) because they deal with the internal administration of Mycenaean kingdoms.

§52. A possible reference to political relations involving the Mycenaeans could be found in the Hittite texts mentioning Aḫḫiyawa, assuming the validity of the link between the words Aḫḫiyawa and Achaeans and/or Achaea (Forrer 1924:9—10; Muhly 1974; Atila 2021:335—337). The first term occurs mainly in diplomatic documents, but also in historical, political, religious, and inventory texts (Beckman et al. 2011; Dickinson 2019; Melchert 2020). These texts have been extensively studied to better understand Aḫḫiyawa’s identity, its relationship with the Hittites, and the history of Western Anatolia (Güterbock 1983; Bryce 1989; Taracha 2001; Bryce 2003; Hope Simpson 2003; Bryce 2018; Greco 2018; Kelder 2018; Taracha 2018; Weeden 2018; Waal 2019; Atila 2021; Blackwell 2021. All with quoted references). However, the connection between Aḫḫiyawa and Mycenaeans is still debated.[1]

§53. Despite the limited and uncertain data available, possible indirect evidence of diplomatic exchanges/relations involving the Mycenaean kingdoms can be identified in the prestigious objects described in some Linear B tablets. Such artifacts may have reached the Mycenaean courts as luxury gifts circulated among the palace elites (Feldman 2006:30; Walsh 2014:211—213) as a possible signifier of political-diplomatic relations. However, this is likely to be indirectly associated, because they were recorded in texts responding to a purpose other than diplomatic.

§54. Most of the goods are furniture and precious vessels made and/or decorated with precious materials such as ebony, gold, silver, ivory, lapis lazuli, blue glass, and semi-precious stones. These paraphernalia are mentioned not only in the Linear B tablets, but also in the Hittite inventory texts and in the Amarna Letters, all of which fall into the same chronological framework (fourteenth–early twelfth century BCE). The Amarnian correspondence explicitly documents the circulation of luxury materials and goods in the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East during the LBA, while the Mycenaean and Hittite administrative texts provide little or no information about the nature of the objects, possible senders, and/or recipients or the reasons for the record, preventing a definitive understanding of whether the recorded items were the result of gift exchanges or locally craftwork consistent with shared patterns of wealth and power.

§55. By comparing Mycenaean written sources with Hittite administrative texts and combining the data with data from the Amarna Letters and archaeology, this paper aims to investigate what information Linear B tablets can indirectly provide on the diplomatic relations of the Mycenaeans with other partners.

The Linear B evidence

§56. The valuable items recorded in the Linear B tablets are mainly luxury furniture and vessels made of precious materials, such as those that are described in the Ta and Tn series from Pylos (Doria 1956; Higgins 1956; Ventris 1956; L. Palmer 1957; Hiller 1971; Gallavotti 1972; Sacconi 1987; Del Freo 1990; Killen 1998; Palaima 1999; Palaima 2000; Varias 2008; Godart 2009; Shelmerdine 2012; Tsagrakis 2012; Varias 2016; Palaima and Blackwell 2020; Aura Jorro 2021; Pierini et al. 2021; Blackwell and Palaima 2021; Morton et al. 2023; Palaima 2023; Killen and Bennet 2024).

§57. The Ta series includes 13 tablets that list “what Phugegwris saw when the king appointed Augewās as da-mo-ko-ro” (PY Ta 711.1). The tablets describe furniture, utensils, and vessels required for an unknown event. From the late fifties, scholars have proposed several hypotheses (Del Freo 1990; Aura Jorro 2021:16—24 for an overview), namely:

- a registration of furniture in a reception hall (Ventris 1956; Sacconi 1971:36—38; Gallavotti 1972; Docs2 334; Del Freo 1990).

- an inventory of furniture stored in a palatial storeroom (Doria 1956; Higgins 1956).

- a temple inventory (Hiller 1971).

- an inventory of funerary goods in Augewās’ grave (Palmer 1957) or used in a funerary feast (Palaima 2023).

- a list of paraphernalia for a ritual ceremony, that included the sacrifice and consumption of animals during a banquet (Killen 1998; Speciale 1999:292; Palaima 2000; Palaima 2004:234; Bennet 2008:151, 154; Palaima and Blackwell 2020; Blackwell and Palaima 2021). The items could be used for both sacrifice and banquet, or just as a ritual sacrifice (Pierini 2021:128—130; Morton et al. 2023).

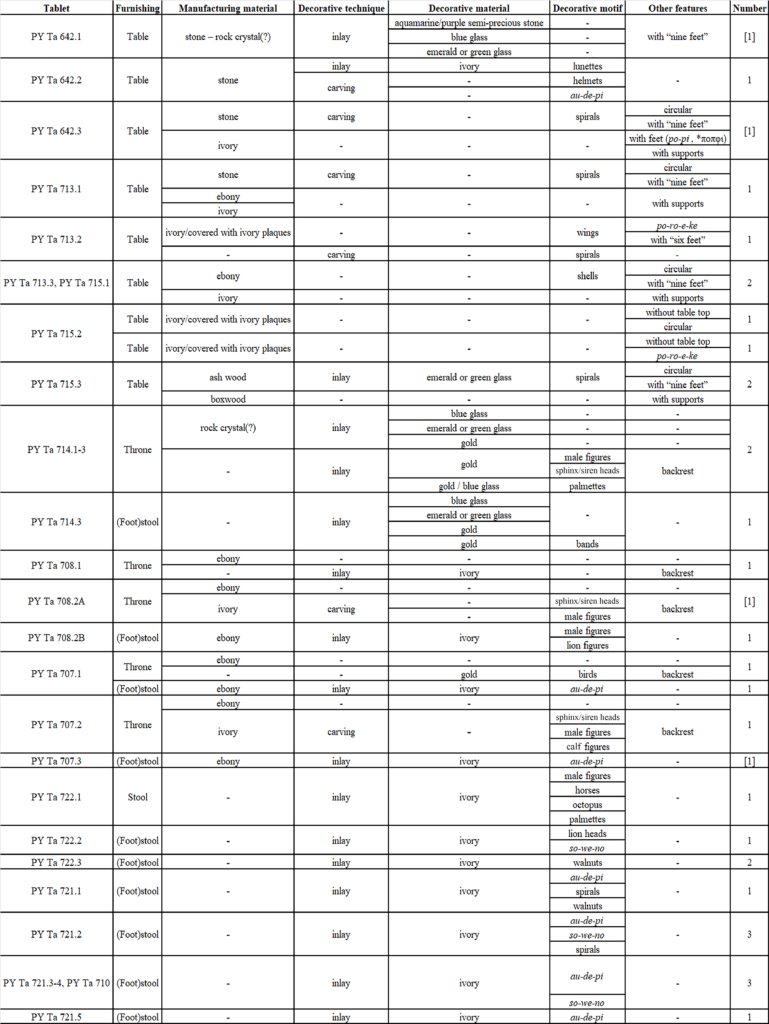

§58. Following Palaima’s sequence, the tablets record: libation vessels, offering vessels, fire implements, tripods, other vessels, slaughtering paraphernalia, and furniture.[2] Furniture included eleven tables (Piquero 2021; Morton et al. 2023:172–178), six thrones,[3] and sixteen (foot)stools (Palaima 2004:115; Tsagrakis 2012:327—329; Perna and Zucca 2021; Pierini 2021:117—118) and appear to be the most luxurious objects in the document, especially in terms of materials[4] and decoration patterns (Table 2). Stone (ra-e-ja), rock crystal? (we-a-re-ja/we-a2-re-jo),[5] false ebony (ku-te-so), boxwood (pu-ko-so), and ivory (e-re-pa-te/-te-jo/a)[6] form the furnishings or parts thereof. Ivory is also used for inlaying (a-ja-me-na/o) furniture, along with gold (ku-ru-so), ku-wa-no, probably blue glass (Docs2:559; Halleux 1969; Nightingale 1998:213—215; Bennet 2008:159—162; Piquero 2015:288—292; Varias 2016:554; Killen and Bennet 2024:787—788),[7] pa-ra-ku, i.e. emerald, green glass or green decoration (DMic s.v.; Piquero 2015; Killen and Bennet 2024:788), and a2-ro[ ]u-do-pi, aquamarine or purple semi-precious stone (Piquero 2021:46; Romani 2021; Killen and Bennet 2024:787). The furniture is also decorated using the carving technique (qe-qi-no-to/qe-qi-no-me-na).

§59. Inlaid and carved decorative motifs are:

- geometric: spirals (to-qi-de), bands (ko-no-ni-pi);

- plant: palmettes (po-ni-ke/-ki-pi), walnut (ka-ru-we/-pi);

- animal: shells (ko-ki-re-ja), wings (pi-ti-ro2-we-sa), birds (o-ni-ti-ja-pi), octopuses (po-ru-po-de), calves (po-ti-pi), horses (i-qo), lions (re-wo-pi), or lion heads (ka-ra-a-pi re-wo-te-jo);

- human: male figures (a-di-ri-ja-te/-pi, a-to-ro-qo), sphinx/siren heads (se-re-mo-ka-ra-a-pi/-o-re: Luján et al. 2017);[8]

- objects: lunettes (me-no-e-ja), helmets (ko-ru-pi);

- unidentified: so-we-no, au-de-pi.

§60. The Ta series provides additional information, including the circular shape of the tables (a-pi-qo-to) and the component parts of the furniture. The thrones have an inlaid backrest (o-pi-ke-re-mi-ni-ja: Luján and Piquero 2022), while the tables may or may not have the top (a-ka-ra-no) and the supports (e-ka-ma-te). Tables are also defined as we-pe-za (‘with six legs’), or e-ne-wo-pe-za (‘with nine legs’: Morton et al. 2023:172–174), although the terms have been alternatively interpreted as indicating the number of leg pieces (Yasur-Landau 2005), whereas the most common Mycenaean tables would have had three legs, as testified by etymological and iconographic evidence (Sabattini 2021).

Table 2. Summary table of the furniture described in the Pylos Ta series.

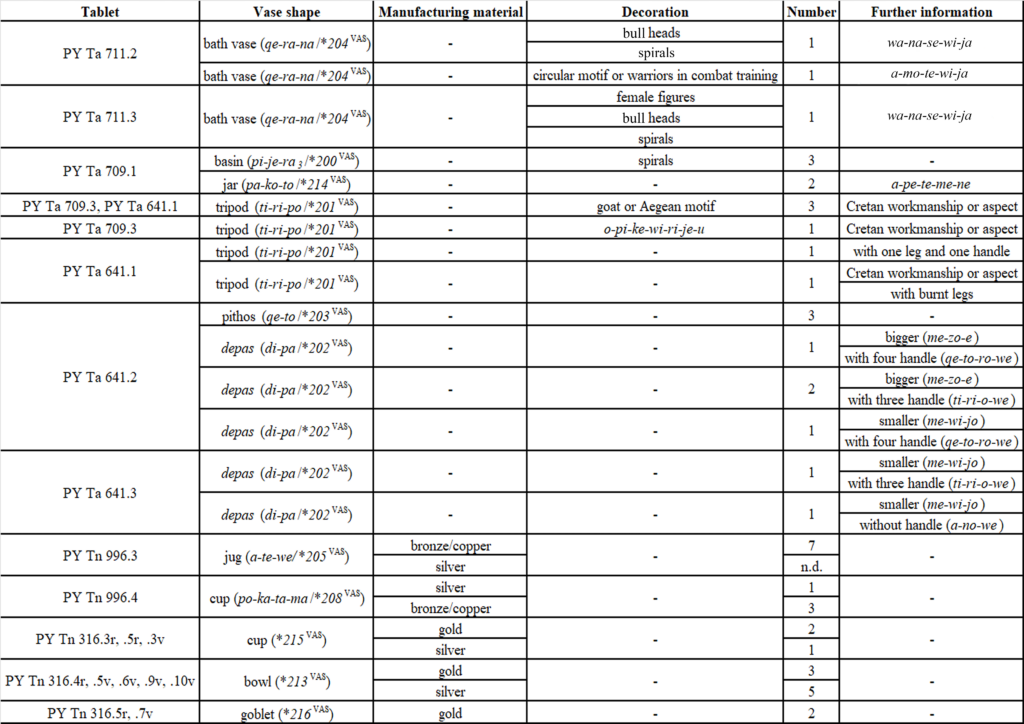

§61. The value of the vases recorded in the Ta series is less clear because the manufacturing materials are not specified but can be inferred from the shape of the vessels (Table 3). Comparison with archaeological evidence shows that di-pa/*202VAS (cf. later /depas/) and qe-to/*203VAS (cf. later /pithos/) would have been pottery vessels, probably not particularly valuable, while qe-ra-na/*204VAS (bath vase: DMic s.v.; Shelmerdine 2012:693), pi-je-ra3/*200VAS (basins), pa-ko-to/*214VAS (jar?), and ti-ri-po/*201VAS (tripod: Russotti 2021) could have been metal vessels, perhaps precious, as suggested by their description (Vandenabeele and Olivier 1979:221—241, 246—257; Dialismas 2001:129—134).

§62. Qe-ra-na and pi-je-ra3 vessels are characterized by the following decorative motifs:

- geometric: shell, spirals (to-qi-de-we-sa);

- animal: bull head (qo-u-ka-ra);

- human: female figures (ku-na-ja);

- uncertain: ko-ro-no-we-sa (either /korōnowessa/, ‘with circular motif’, or /klonowessa/, ‘with warriors in combat training’: DMic s.vv.; Varias 2016:554), a3-ke-u (/aigeus/, with a goat or an Aegean or a high waves motif: Biraschi 1993:78—79; Melena 2014, 213; Docs3 s.v.; Killen and Bennet 2024, 784—786), *34-ke-u, that has been read either as a graphic variant of a3-ke-u or as ru2-ke-u (/lukeus/, ‘decorated with a wolf’ or /lugkeus/, ‘decorated with a lynx’);[9]

- unidentified: a-pe-te-me-ne, o-pi-ke-wi-ri-je-u, so-we-ne-ja, au-de-we-sa.

§63. The similarity of the decorative patterns to those found on furniture supports the hypothesis that metal vessels are also valuable.

§64. Furthermore, qe-ra-na are qualified as wa-na-se-wi-ja and a-mo-te-wi-ja, adjectives perhaps indicating “a type, shape or material conventionally so named” (Killen and Bennet 2024:782—783), that can be derived from names in -eus, respectively *wa-na-se-u (potentially, an official connected to the wa-na-sa, ‘queen’) and a-mo-te-u (‘wheel-maker’). The tripods would be of Cretan workmanship or aspect (ke-re-si-jo we-ke: Heubeck 1986; Pierini and Rosamilia 2021. Otherwise, Biraschi 1993), and in two cases are damaged because one has burnt legs and another only a leg and a handle (PY Ta 641.1: DMic s.v.; Varias 2016:555; Russotti 2021:37—38. Alternatively, Doria 1973:27—35; Biraschi 1993).

§65. In contrast, the vases recorded in the two tablets of the Tn series could have had a high value due to their manufacturing materials (Table 3). Indeed, in PY Tn 996 jugs (a-te-we/*205VAS) and cups (po-ka-ta-ma/*208VAS) are made of bronze (*140/AES) and gold (*141/AUR), while in PY Tn 316 bowls (*213VAS), cups (*215VAS), and goblets (*216VAS) (Vandenabeele and Olivier 1979:183—185, 209—216, 252—253) are made of gold (*141/aur). In both tablets logogram *141 appears in two slightly different shapes (Godart 2009:112), which have been interpreted as graphic variants (*141a and *141b), perhaps with a different meaning: *141a would have represented gold, while *141b would have represented silver (Godart 2009:113–114; de Fidio 2024:267—268). Nevertheless, the decision whether to consider the two signs as different logograms is still to be made (Nosch and Landenius-Enegren 2017:837). Whether it was gold or silver, logogram *141 highlights that the vases recorded in the Tn series were made of precious metals.

Table 3. Summary table of the vases recorded in the Pylos T-class.

The Hittite inventory texts

§66. Hittite inventory texts record an extensive number of goods, including high-value items similar to those mentioned in the Linear B tablets, sometimes providing additional information about the occasion for which the documents were written or the origin and/or destination of the objects.

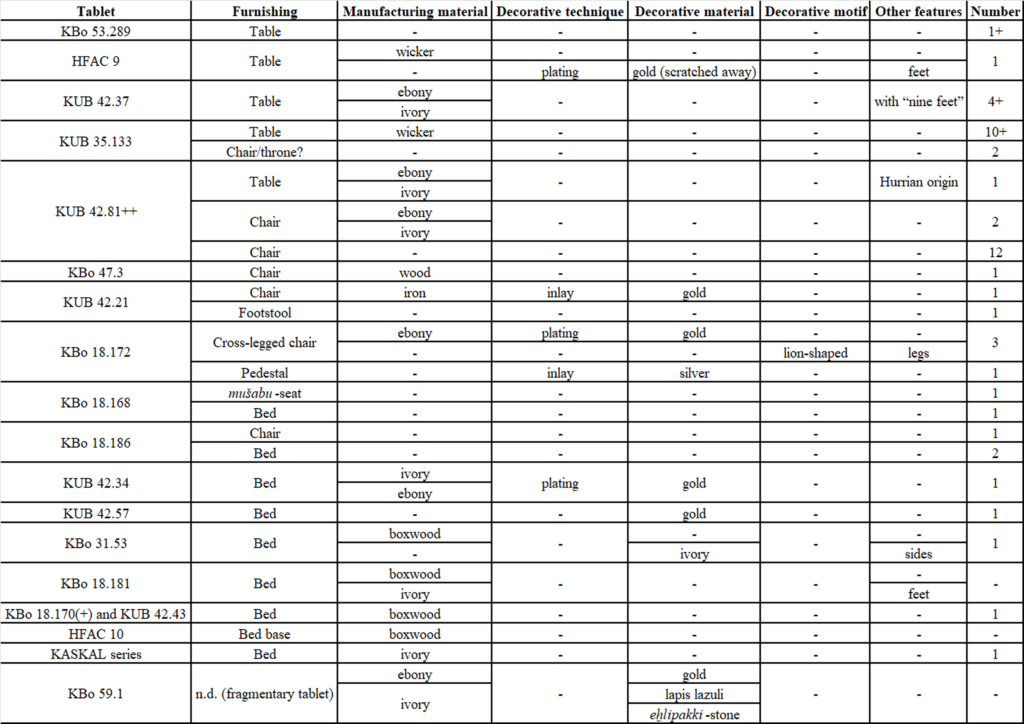

§67. As for the furniture (Table 4), tables (GIŠBANŠUR) are recorded in KBo 53.289, HFAC 9, and KUB 42.37 (Košak 1982:151—152; Siegelová 1986:70—71; Burgin 2022b:518—523). In HFAC 9, the table is made of wicker (GIŠḫariuzzi-), with feet covered with gold (KÙ.SI22), while in KUB 42.37 the tables have feet with nine pieces made of ivory (GÌR ZU9 AM.SI) and nine made of ebony (GIR GIŠESI) (Yasur-Landau 2005:300—302; Burgin 2022b:521—523).

§68. The fest ritual fragment KUB 35.133 lists more than ten tables and two chairs (GIŠŠÙ.A), one of them for the king, possibly the throne (https://www.hethport.uni-wuerzburg.de/TLHdig/tlh_xtx.php?d=KUB%2035.133). A wood chair (GIŠšarpa) is also mentioned in the fragment KBo 47.3 (Burgin 2022b:271–272) and one inlaid with gold (KÙ.SI22 GAR.RA) as well as a stool (GIŠGÌR.GUB) are listed in KUB 42.21 (Košak 1982:46–47; Siegelová 1986:137–139; Burgin 2022b:225–228).

§69. Beds are also recorded, such as the one made of ivory and ebony and overlaid with gold (GIŠ.KIN KÙ.SI22) in KUB 42.34, one probably decorated with gold in KUB 42.57, and another made of boxwood (GIŠTÚG) in KBo 31.53.[10]

§70. In some texts, the furniture is associated with vessels, such as in KUB 42.81++ and KBo 18.172 (Košak 1982:98—100; Siegelová 1986:490—493; Burgin 2022b:69—72, 403—408). The first lists gold and silver zoomorphic vessels/BIBRI[11], cups ((DUG)GAL), chairs, and one Hurrian table made of ebony and ivory. The second records gold cups inlaid with semi-precious stones, silver vessels, and chairs made of ebony and overlaid with gold.

Table 4. Summary table of the furniture recorded in Hittite inventory texts.

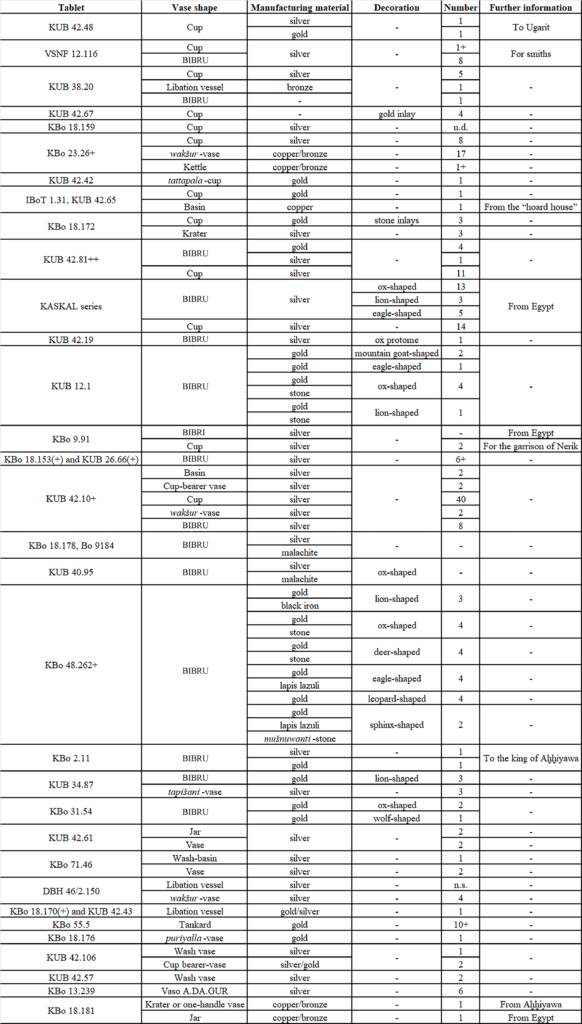

§71. Cups, zoomorphic vessels, and other vessels, made of precious metals (Table 5), are recorded in other texts,[12] where they sometimes appear as gifts. For example, KUB 42.48 lists diplomatic gifts potentially addressed to Ugarit, that includes two cups, one made of gold, the other of silver (Košak 1982:126—127; Siegelová 1986:242—245; Burgin 2022b:216—218). VSNF 12.116 is a preliminary inventory of chests which contains incoming gifts, including silver cups and BIBRI for smiths (Burgin 2022b:24—30). IBoT 1.31 and KUB 42.65 are part of a preliminary inventory of chests containing incoming gifts and tributes, that include a gold cup and copper vases for washing (warpuwaš and NÍG.ŠU.LUḪ URUDU) (Košak 1982:4—10, 158—159; Siegelová 1986:80—85; Burgin 2022b:37—47). Also, KBo 9.91 (Košak 1982:24—29; Siegelová 1986:332—335; Burgin 2022b:283—290) is an inventory of chests which contain clothes, garments, utensils, and silver zoomorphic vessels coming from Egypt, and two silver cups for the garrison of Nerik. Another example is KBo 2.11, a letter that mentions gold and silver rhyta as gifts originally intended for the pharaoh but redirected to the Aḫḫiyawa king (Beckman et al. 2011:149; Waal 2019:16).

§72. Lion-shaped BIBRI together with cow-, deer-, eagle-, leopard-, and sphinx-shaped BIBRI made of gold, black iron, stone, lapis lazuli, and mušnuwanti-stone are listed in KBo 48.262+ and gold lion-shaped BIBRI are recorded in KUB 34.87 as votive objects for several deities, along with silver vases, utensils, and weapons (Burgin 2022b:315—319, 391—402).

§73. Luxury materials like gold, silver, ivory, boxwood, lapis lazuli, carnelian, and others are also used to make and decorate other objects, such as boxes (GIŠDUB.ŠEN) and chests (GIPISAN), (wool) combs (GIŠGA.ZUM), jewelry, and statues of/for Hittite deities.[13]

§74. Texts that are part of the KASKAL series are of particular interest, with administrative texts dealing with the transportation of durable goods, that have in common a similar formula characterized by the presence of the Sumerogram KASKAL, meaning ‘way/journey/road’ (Košak 1982:10—23, 31—45, 125—126, 173—174, 181; Siegelová 1986:388—438; Burgin 2022a:144—148; Burgin 2022b:325—356). They list items made of precious materials and often inform on their provenience, like rings made of gold, lapis lazuli, and carnelian, coming from Egypt, Babylon, and Lukka.

Table 5. Summary table of the vases recorded in Hittite texts.

Comparison and integration of data

§75. The presented analysis revealed that the luxury objects described in Mycenean and Hittite texts share some similar aspects whilst also differing in others.

§76. A common element between Mycenean and Hittite furniture is the number of feet or feet pieces of tables, which equal nine, as well as the manufacturing material, as shown by the ivory feet of the tables described in PY Ta 642.3 and KUB 42.37.

§77. As for the manufacture materials, ebony, ivory, and gold are mentioned in Mycenaean and Hittite texts as well as in the Amarna Letters. Most beds, headrests, stools, chairs, and thrones recorded in EA 5, EA 14, EA 31, EA 34, and EA 120 are made of ebony, with ivory in some cases, such as a bed in EA 5, three headrests in EA 14, or inlaid ivory, such as ten chairs listed in EA 31, with gold plating (uḫḫuzu) used for decoration (Rainey 2015:76—79, 112—127, 326—329, 336—339, 632—635, 1329—1330, 1342—1345, 1378—1379, 1464—1465, with previous quoted editions Moran 1992; Liverani 1998; Liverani 1999). Boxwood appears as a raw material offered by the governor of Alašiya to Egypt in exchange for ivory (EA 40) (Rainey 2015:356—357, 1385—1386, with previous quoted editions Moran 1992; Liverani 1999), whilst in the Mycenaean and Hittite texts, which record it as a manufacturing material for a table in PY Ta 715.3 and beds in KBo 18.181, KBo 18.170(+)–KUB 42.43, KBo 31.35, and HFAC 10.

§78. The Ta series reveals additional differences in recorded materials because, besides ebony, boxwood, ivory, and gold, it mentions blue glass (ku-wa-no), green glass or emerald (pa-ra-ku), and semi-precious stones as materials for furniture decoration.

§79. Furthermore, the decoration techniques differ slightly: Linear B tablets mention inlays and carving, whereas Hittite texts and Amarna Letters mention plating (GIŠ.KIN and uḫḫuzu respectively) rather than carving, in addition to inlays.

§80. Decorative patterns distinguish furniture recorded on Linear B tablets from those mentioned in Hittite and Amarnian texts. The Ta series provides detailed information on decorative motifs for furniture, unlike the Hittite texts and Amarna Letters. The only exception is the lion motif, which appears on both Linear B and Hittite tablets. On the one hand, two ta-ra-nu were decorated with ivory lion-shaped inlays in PY Ta 708.3 and PY Ta 722.2; on the other, KBo 18.172 records three ebony crossed-leg chairs with gold plating and ivory lion-shaped feet.

§81. As a result, although Mycenaean and Hittite furniture share some elements, the furnishings described in the Hittite and Amarnian texts are more similar. This situation seems to reduce the likelihood that furniture recorded on Linear B tablets were obtained through inter-regional gift-exchanges.

§82. The available documentation instead suggests that the Mycenaean tables and seats may have been produced locally using precious imported raw materials, on the one hand adapting to shared etiquettes in the LBA courts, consistent with the idea of an “International koine” (Walsh 2016:194—222; Feldman 2006:1—71), whilst on the other hand considering the possible involvement of itinerant craftsmen to produce such luxury objects (Feldman 2006:12, 125—126). This hypothesis is supported by the reference of specialized craftspeople in the processing of non-local materials (ku-wa-no-wo-ko for blue glass, ku-ru-so-wo-ko for gold, pi-ri-je-te-re perhaps for ivory), in the Linear B corpus (Voutsa 2001:155—160), and in archaeological evidence of artisanal activities related to ivory, blue glass, and other precious materials.[14] The Uluburun wreck confirms this assumption because its cargo and possible destination towards the Aegean (Bloedow 2005:340; Cline and Yasur-Landau 2007) suggest that high-value raw resources, including ebony, ivory, and blue glass, which are also mentioned in the Pylos Ta series, would arrive in Mycenaean Greece (Caubet 1998:105; Bachhuber 2006:351). The same materials also appear in the Amarna Letters as commodities exchanged between Great Kings, as well as between the pharaoh and the vassal rulers, confirming their circulation in the Near East and Eastern Mediterranean. Furthermore, Hittite inventory texts that record votive statues for local deities made of ebony, gold, and ivory support the hypothesis of local production because they indicate that the Hittites used imported raw precious materials for internal purposes. However, the possible local production of Mycenaean furniture does not rule out that such precious objects were exchanged as gifts among the Mycenaean kings.

§83. In contrast, greater consistency has emerged regarding the vessels, as evidenced by the gold and silver cups mentioned in PY Tn 316 and Hittite inventories KUB 42.48, IBoT 1.31, KUB 42.65, and the KASKAL series. The latter record incoming gifts, perhaps from Ugarit or Egypt, with the queen present, proving the import of precious metal cups into Anatolia and the official character of the entry process.

§84. Hittite texts also mention zoomorphic vessels made of precious materials as diplomatic gifts (KBo 2.11, KBo 48.262+) as well as the Amarna Letter EA 41, which mentions a silver deer-shaped vessel promised to Amenophi IV by the Hittite king Suppiluliuma (Rainey 2015:358—361, 1386—1387, with previous quoted editions Moran 1992; Liverani 1999). Zoomorphic vessels, as appropriate offerings in elite contexts, are supported by archaeological evidence, for example a silver stag-shaped vessel of Anatolian origin discovered in the Shaft Grave IV of Circle A at Mycenae (Cline 1994:213–214; Koehl 1995; Koehl 2013; Stos-Gale 2014:199).

§85. These pieces of evidence provide credence to the hypothesis that the two qe-ra-na decorated with bull heads in Mycenaean tablet PY Ta 711 could have been obtained as diplomatic gifts and made of silver or, perhaps, gold.

§86. Based on the examined sources, the vases recorded in the Linear B tablets may have been imported as gifts accompanying diplomatic relations with the Great Kings.[15]

Conclusions

§87. In summary, although the Linear B tablets do not explicitly record diplomatic relations or gift exchanges, mentioning precious objects seems to provide complementary indirect information, which may help in increasing knowledge on the nature of the Mycenaean high-level contacts. On the one hand, luxury furniture showed that trade contacts ensured the entry of both the luxury materials of which they were made, and the ideas behind their precise stylistic articulation (Walsh 2014; Caubet 1998:109—110). The local processing of valuable imported materials to produce luxury items shows the intention to enjoy and flaunt the same prestigious goods exchanged by the Great Kings, following a pattern of wealth and power shared throughout the Eastern Mediterranean (Caubet 1998; Manning and Hulin 2005:285; Walsh 2014).[16] On the other hand, the precious vessels that match with those exchanged as royal gifts proved to be a valid indicator that gift-exchanges also involved Mycenaeans, who would, therefore, have been included in the Great Kings’ “club”.

§88. In the light of all this, the question in the title can be answered. The analysis of the Linear B tablets from a different perspective provides information that improves our understanding of the Mycenaeans’ diplomatic relations and, above all, on the exchange of goods that accompanied them.

§89. Bibliography

Archives = Godart, L., and A. Sacconi. 2019-2020. Les archives du roi Nestor: Corpus des inscriptions en linéaire B de Pylos. 2 vols. Pasiphae 13-14. Pisa and Rome.

Aura Jorro, F. 2021. “Las interpretaciones de la serie Ta de Pilo en su contexto.” In Pierini et al. 2021:7—26.

Atila, C. 2021. “The Ahhiyawa Question: Reconsidered.” Belleten 85/3:333—359.

Bachhuber, C. 2006. “Aegean Interest on the Uluburun Ship.” American Journal of Archaeology 110/3:345—363.

Beckman, G., T. Bryce, and E. H. Cline. 2011. The Ahhiyawa Texts. Atlanta.

Bennet, J. 2008. “PalaceTM: Speculations on Palatial Production in Mycenaean Greece with (Some) Reference to Glass.” In Vitreous Materials in the Late Bronze Age Aegean, ed. C. M. Jackson, and E. C. Wager, 151—172. Oxford.

Bennet, J., and P. Halstead. 2014. “O-no! Writing and Righting Redistribution.” In KE-RA-ME-JA. Studies Presented to Cynthia W. Shelmerdine, ed. D. Nakassis, J. Gulizio and S. A. James, 271—282. Prehistory Monographs 46. Philadelphia.

Biraschi, A. M. 1993. “Miceneo ke-re-si-jo we-ke. A proposito della tavoletta dei tripodi (PY Ta 641).” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 32:77—84.

Blackwell, N. G. 2021. “Ahhiyawa, Hatti and diplomacy: implications of Hittite misperceptions of the Mycenaean world.” Hesperia 90:191—231.

Blackwell, N. G., and T. Palaima. 2021. “Further Discussion on pa-sa-ro on Pylos Ta 716: Insights from the Ayia Triada Sarcophagus.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 7:21—37.

Bloedow, E. F. 2005. “Aspects of trade in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean: what was the ultimate destination of the Uluburun ship?.” In Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Proceedings of the 10th International Aegean Conference Athens, Italian School of Archaeology, 14-18 April 2004, ed. R. Laffineur, and E. Greco, 335—341. Aegeum 25. Liège and Austin.

Bryce, T. 1989. “Ahhiyawans and Mycenaeans. An Anatolian Viewpoint.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 8:297—310.

Bryce, T. 2003. “Relations between Ḫatti and Aḫḫiyawa in the Last Decades of the Bronze Age.” In Hittite Studies in Honor of Harry A. Hoffner Jr. on the Occasion of His 65th Birthday, ed. G. Beckman, R. Beal, and G. McMahon, 59—72. Winona Lake, IN.

Bryce, T. 2018. “The kingdom of Ahhiyawa: a Hittite perspective.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 4:191—197.

Burgin, J. 2022a. Studies in Hittite Economic Administration. A New Edition of the Hittite Palace-Temple Administrative Corpus and Research on Allied Texts Found at Ḫattuša. Vol. 1. Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten. Wiesbaden.

Burgin, J. 2022b. Studies in Hittite Economic Administration. A New Edition of the Hittite Palace-Temple Administrative Corpus and Research on Allied Texts Found at Ḫattuša. Vol. 2. Studien zu den Boğazköy-Texten. Wiesbaden.

Caubet, A. 1998. “The International Style: a point of view from the Levant and Syria.” In The Aegean and the Orient in the Second Millennium, Proceedings of the 50th Anniversary Symposium, University of Cincinnati, 18–20 April 1997, ed. E. H. Cline, and D. Harris-Cline, 105—113. Aegaeum 18. Liège andAustin.

Cline, E. 1987. “Amenhotep III and the Aegean: A Reassessment of Egypto-Aegean Relations in the 14th Century B.C.” Orientalia 56/1:1—36.

Cline, E. 1993. “Contact and Trade or Colonization? Egypt and the Aegean in the 14th-13th Centuries B.C.” Minos 25-26 (1990–1991):7—36.

Cline, E. 1994. Sailing the Wine-dark Sea. International Trade and the Late Bronze Age. British Archaeological Reports, International Series 591. Oxford.

Cline, E., and A. Yasur-Landau. 2007. “Musings from a Distant Shore. The Nature and Destination of the Uluburun Ship and its Cargo.” Tel Aviv 34/2:125—141.

de Fidio, P. 2024. “Economy.” In Docs3:267—289.

Del Freo, M. 1990. “Miceneo a-pi to-ni-jo e la serie Ta di Pilo.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 28:287—331.

Dialismas, A. 2001. “Metal artefacts as recorded in the Linear B tablets.” In Manufacture and Measurement. Counting, Measuring and Recording. Craft Items in Early Aegean Societies, ed. A. Michailidou, 120—143. Meletemata 33. Athens.

Dickinson, O. 2019. “The Use and Misuse of the Ahhiyawa Texts.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 5:7—22.

DMic = Aura Jorro, F. 1985-1993. Diccionario micénico. 2 vols. Madrid.

Docs2 = Ventris, M., and J. Chadwick. 1973. Documents in Mycenaean Greek. 2nd ed. Cambridge.

Docs3 = J. Killen ed. 2024. The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Cambridge.

Doria, M. 1956. Interpretazioni di testi micenei; le tavolette della classe Ta di Pilo. Trieste.

Doria, M. 1973. Varia Mycenaea. Trieste.

Egetmeyer, M. 2022. “Woher kam der Mann von Ahhiya?.” Kadmos 61:1—36.

Feldman, M. 2006. Diplomacy by Design, Luxury Arts and ‘International Style’ in the Ancient Near East, 1400-1200 BCE. Chicago.

Forrer, E. 1924. “Vorhomerische Griechen in den Keilschrifttexten von Boghazköi.” Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient Gesellschaft 83:1—22.

Gallavotti, C. 1972. “Note omeriche e micenee, III: la sala delle cerimonie del palazzo di Nestore.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 15:24—32.

Godart, L. 2009. “I due scribi della tavoletta Tn 316.” Pasiphae. Rivista di filologia e antichità egee 3:99—115.

Greco, A. 2018. “‘Ecco … ha assoldato contro di noi i re degli Ittiti e i re di ‘Ahhijawa’ per assalirci’. Alcune riflessioni sul contesto economico, politico e sociale del fenomeno Ahhijawa.” Pasiphae. Rivista di filologia e antichità egee 12:105—117.

Güterbock, H. 1983. “The Hittites and the Aegean World: Part 1. The Ahhiyawa Problem Reconsidered.” American Journal of Archaeology 87:133—143.

Halleux, R. 1969. “Lapis-lazuli, Azurite ou Pâte de verre? A propos de Kuwano et Kuwanowoko dans les Tablettes Mycéniennes.” Minos 9:47—66.

Hart, G. 1993. “Mycenaean se-re-mo-ka-ra-a-pi and se-re-mo-ka-ra-o-re.” Minos 25-26:319—329.

Heubeck, A. 1986. “Mykenisch ke-re-si-jo we-ke.” Munchener Studien zur Sprachwissenschaft 47:81—85.

Higgins, R. 1956. “The archaeological background to the furniture tablets from Pylos.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 3:39—44.

Hiller, S. 1971. “Beinhaltet die Ta-Serie ein Kultinventar?.” Eirene 9:69—86.

Hope Simpson, R. 2003. “The Dodecanese and the Ahhiyawa Question.” Annual of the British School at Athens 98:203—237.

Jasink, A. M. 2005. “Mycenaean Means of Communication and Diplomatic Relations with Foreign Royal Courts.” In Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Proceedings of the 10th International Aegean Conference Athens, Italian School of Archaeology, 14-18 April 2004, ed. R. Laffineur, and E. Greco, 59—67. Aegaeum 25. Liège and Austin.

Judson, A. 2020. The Undeciphered Signs of Linear B: Interpretation and Scribal Practices. Cambridge Classical Studies. Cambridge.

Kelder, J. 2012. “Ahhiyawa and the World of the Great Kings: A Re-evaluation of Mycenaean Political Structures.” Talanta 44:41—52.

Kelder, J. 2018. “The Kingdom of Ahhiyawa: Facts, Factoids, and Probabilities.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 4:200—208.

Kempinski, A., and S. Košak. 1977. “Hittite Metal “Inventories” (CTH 242) and their Economic Implications.” Tel Aviv 4:87—93.

Killen, J. 1998. “The Pylos Ta Tablets Revisited.” Bulletin de correspondance hellénique 122/2:421—422.

Killen, J. 2008. “Mycenaean Economy.” In A Companion to Linear B. Mycenaean Greek Texts and their World. Volume 1, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies, 159—200. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 120. Louvain-la- Neuve.

Killen, J., and J. Bennet. 2024. “Finished Products I: Vessels and Furniture.” In Docs3:758—786.

Koehl, R. B. 1995. “The Silver Stag ‘BIBRU’ from Mycenae”. In The Age of Homer: A Tribute to Emily Townsend Vermeule, ed. J. B. Carter and S. P. Morris, 61–66. Austin.

Koehl, R. B. 2013. “Bibru and Rhyton: Zoomorphic Vessels in the Near East and Aegean”. In Cultures in Contact: From Mesopotamia to the Mediterranean in the Second Millennium B.C., ed. J. Aruz, S. B. Graff, and Y. Rakic, 238–247. New York and New Haven.

Košak, S. 1982. Hittite Inventory Texts (CTH 241-250). Texte der Hethiter 10. Heidelberg.

Liverani, M. 1994. Guerra e Diplomazia nell’Antico Oriente, 1600-1100 a.C. Bari.

Liverani, M. 1998. Le lettere di el-Amarna. Le lettere dei Piccoli Re. Brescia.

Liverani, M. 1999. Le lettere di el-Amarna. Le lettere dei Grandi Re. Brescia.

Luján, E. R., and A. Bernabé. 2012. “Ivory and Horn Production in Mycenaean Texts.” In Kosmos: Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 13th International Aegean Conference University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21-26 April 2010, ed. M.-L. Nosch, and R. Laffineur, 627—638. Aegaeum 33. Leuven and Liège.

Luján, E. R., J. Piquero, and F. Díez Platas. 2017. “What did Mycenaean Sirens Look Like?”. In Nosch and Landenius-Enegren:435—460.

Luján, E. R., and J. Piquero. 2022. “Mycenaean o-pi-ke-re-mi-ni-ja”. In TA-U-RO-QO-RO: Studies in Mycenaean Texts, Language and Culture in Honor of José Luis Melena Jiménez, ed. J. Méndez Dosuna, T. G. Palaima, C. Varias García, 121—130. Hellenic Studies 94. Washington, DC.

Manning, S. W., and L. Hulin. 2005. “Maritime Commerce and Geographies of Mobility in the Late Bronze Age of the Eastern Mediterranean: Problematizations.” In The Archaeology of Mediterranean Prehistory, ed. E. Blake, and A. B. Knapp, 270—302. Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology 6. Oxford.

Mascheroni, L. M. 1979. “Un’interpretazione dell’inventario KBo XVI 83+XXIII 26 e i processi per malversazione alla corte di Ḫattuša.” In Studia Mediterranea Piero Meriggi Dicata, ed. O. Carruba, 353—371. Studia Mediterranea 1. Pavia.

Mauss, M. 1925. Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l’échange dans les sociétés archaïques. Paris.

Melchert, H. C. 2020. “Mycenaean and Hittite Diplomatic Correspondence: Fact and Fiction.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/mycenaean-and-hittite-diplomatic-correspondence-fact-and-fiction/

Melena, J. L. 2014. “Filling gaps in the Mycenaean Linear B additional syllabary: the case of syllabogram *34.” In Ágalma. Ofrenda desde la Filología Clásica a Manuel García Teijeiro, ed. A. Martínez Fernández, B. Ortega Villaro, H. Velasco López, and H. Zamora Salamanca, 207—226. Valladolid.

Moran, W. L. 1992. The Amarna Letters. Baltimore and London.

Morton, J., N. G. Blackwell, and K. W. Mahoney. 2023. “Sacrificial Ritual and the Palace of Nestor: A Reanalysis of the Ta Tablets.” American Journal of Archaeology 127/2:167—187.

Muhly, J. D. 1974. “Hittites and Achaeans: Ahhijawa redomitus.” Historia 23:129—145.

Nightingale, G. 1998. “Glass and the Mycenaean Palaces of the Aegean.” In The Prehistory & History of Glassmaking Technology, ed. P. McCray, 213—215. Westerville, OH.

Nosch, M.-L., H. Landenius-Enegren eds. 2017. Aegean Scripts: Proceedings of the 14th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, Copenhagen, 2-5 September 2015. Incunabula Graeca 105. Rome.

Olivier, J.-P. 1997. “El comercio micénico desde la documentación epigráfica.” Minos 31-32:275—292.

Palaima, T. 1999. “KN 02 – Tn 316.” In Floreant Studia Mycenaea: Akten des X. Internationalen Mykenologischen Colloquiums in Salzburg vom 1.–5. Mai 1995, ed. S. Deger-Jalkotzy, S. Hiller, and O. Panagl, 437—461. Vienna.

Palaima, T. 2000. “The Pylos Ta series: from Michael Ventris to the new millennium.” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies 44:236—237.

Palaima, T. 2004. “Sacrificial Feasting in the Linear B Documents”. In The Mycenaean Feast, ed. J. C. Wright, 217—246. Hesperia 73/2. Princeton.

Palaima, T. 2023. “The Pylos Ta Series and the Process of Inventorying Ritual Objects for a Funerary Banquet.” In Processions: Studies of Bronze Age Ritual and Ceremony presented to Robert B. Koehl, ed. J. Weingarten, C. F. Macdonald, J. Aruz, L. Fabian, and N. Kumar, 222—233. Oxford.

Palaima, T., and N. G. Blackwell. 2020. “Pylos Ta 716 and Mycenaean Ritual Paraphernalia: a reconsideration.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 6:67—96.

Palmer, L. R. 1957. “A Mycenaean tomb inventory.” Minos 5:58—92.

Perna, M., and R. Zucca. 2021. “Il ta-ra-nu nel Mediterraneo antico”. In Pierini et al. 2021:97—104.

Pierini, R. 2021. “Mycenaean wood: re-thinking the function of furniture in the Pylos Ta tablets within Bronze Age sacrificial practices.” In Pierini et al. 2021:107—136.

Pierini, R., A. Bernabé, and M. Ercoles. 2021. Thronos: Historical Grammar of Furniture in Mycenaean and Beyond. Eikasmos: Quaderni Bolognesi di Filologia Classica, Studi 32. Bologna.

Pierini, R. and E. Rosamilia. 2021. “Made in Crete: Tripods and other imported luxury items in Mycenaean and Classical Greek.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/mast-fall-seminar-2021-friday-december-17/

Piquero, J. 2015. “Incrustaciones con vidrios de colores en Pilo. Análisis lingüístico y arqueológico de micénico pa-ra-ku-we.” In Orientalística en tiempos de crisis: actas del VI Congreso Nacional del Centro de Estudios del Próximo Oriente, ed. A. Bernabé, and J. A. Álvarez-Pedrosa Núñez, 285—296. Zaragoza.

Piquero, J. 2021. “The tables of the Pylos Ta series: text and context.” In Pierini et al. 2021:43—54.

Rainey, A. F. 2015. The El-Amarna Correspondence. Leiden.

Romani, E. 2021. “‘The odd couple’: morpho-syntactic analysis of a-ja-me-na a2-ṛọ[ ]ụ-do-pi.” In Pierini et al. 2021:147—154.

Russotti, A. 2021. “ti-ri-po: unusual description for an every-day object.” In Pierini et al. 2021:31—41.

Sabattini, P. 2021. “Were Mycenaean tables three-footed? Etymological, iconographical, archaeological, and contextual remarks.” In Pierini et al. 2021:65—74.

Sacconi, A. 1971. Un problema di interpretazione omerica: La freccia e le asce del libro XXI dell’Odissea. Rome.

Sacconi, A. 1987. “La tavoletta di Pilo Tn 316: una registrazione di carattere eccezionale?.” In Studies in Mycenaean and Classical Greek Presented to John Chadwick, ed. J. T. Killen, J. L. Melena, and J.-P. Olivier, 551—555. Minos 20–22. Salamanca.

Shelmerdine, C. W. 2012. “Mycenaean Furniture and Vessels: Text and Image.” In Kosmos: Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 13th International Aegean Conference University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21-26 April 2010, ed. M.-L. Nosch, and R. Laffineur, 685—695. Aegeum 33. Leuven and Liège.

Siegelová, J. 1986. Hethitische Verwaltungspraxis im Lichte der Wirtschafts- und Inventardokumente. Prague.

Singer, I. 2011. “Aḫḫijawans Bearing Gifts.” In The Calm before the Storm: Selected Writings of Itamar Singer on the Late Bronze Age in Anatolia and the Levant, ed. I. Singer, 459—466. Writings from the Ancient World Supplement 1. Atlanta.

Snodgrass, A. M. 1991. “Bronze Age Exchange: A Minimalist Position.” In Bronze Age Trade in the Mediterranean, ed. N. Gale, 15—20. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 90. Gothenburg.

Speciale, S. 1999. “La tavoletta PY Ta 716 e i sacrifici di animali.” In Ἐπί πόντον πλαζόμενοι. Simposio italiano di Studi Egei dedicato a Luigi Bernabò Brea e Giovanni Pugliese Carratelli, Roma 18-20 febbraio 1998, ed. V. La Rosa, D. Palermo, and L. Vagnetti, 291—297. Rome.

Stos-Gale, Z. A. 2014. “Silver vessels in the Mycenaean Shaft Graves and their origin in the context of the metal supply in the Bronze Age Aegean.” In Metalle der Macht–Frühes Gold und Silber: 6. Mitteldeutscher Archäologentag vom 17. bis 19. Oktober 2013 in Halle (Saale), ed. H. Meller, R. Risch, and E. Pernicka, 183—208. Halle (Saale).

Taracha, P. 2001. “Mycenaeans, Ahhiyawa, and Hittite Imperial Policy in the West: A Note on KUB 26.91.” In Kulturgeschichten: Altorientalistische Studien für Volkert Haas zum 65. Geburtstag, ed. T. Richter, D. Preschel, and J. Klinger, 417—422. Saarbrücken.

Taracha, P. 2018. “Approaches to Mycenaean-Hittite Interconnections in the Late Bronze Age.” In Change, Continuity, and Connectivity: North-Eastern Mediterranean at the Turn of the Bronze Age and in the Early Iron Age, ed. Ł. Niesiołowski-Spanò, and M. Węcowski, 8—22. Philippika 118. Wiesbaden.

Tournavitou, I. 1995. The ‘Ivory Houses’ at Mycenae. The British School at Athens Supplementary Volume 24. London.

Tsagrakis, A. 2012. “Furniture, Precious Items and Materials recorded in the Linear B archives.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 54:323—341.

Vandenabeele, F., and J.-P. Olivier. 1979. Les idéogrammes archéologiques du Linéaire B. Études crétoises 24. Paris.

Varias, C. 2008. “Observations on the Mycenean Vocabulary of Furniture and Vessels.” In Colloquium Romanum: atti del XII colloquio internazionale di micenologia, Roma, 20-25 febbraio 2006, ed. A. Sacconi, M. Del Freo, L. Godart, and M. Negri, 775—793. Pasiphae 2. Pisa and Rome.

Varias, C. 2016. “Testi relativi a mobilio e vasi pregiati.” In Manuale di epigrafia micenea: Introduzione allo studio dei testi in lineare B, ed. M. Del Freo, and M. Perna, 551—565. Padua.

Ventris, M. 1956. “Mycenaean furniture on the Pylos tablets.” Eranos 53:109—124.

Voutsa, K. 2001. “Mycenaean craftsmen in palace archives: Problems in interpretation.” In Manufacture and Measurement. Counting, Measuring and Recording. Craft Items in Early Aegean Societies, ed. A. Michailidou, 144—165. Meletemata 33. Athens.

Waal, W. 2019. “My Brother, A Great King, My Peer: Evidence for a Mycenaean Kingdom from Hittite Texts.” In From ‘LUGAL.GAL’ to ‘wanax’. Kingship and Political Organisation in the Late Bronze Aegean, ed. J. Kelder, and W. Waal, 9—29. Leiden.

Walsh, C. 2014. “The high life: courtly etiquette in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean.” In Current Research in Egyptology 2013. Proceedings of the 14th Annual Symposium, University of Cambridge, United Kingdom, March 19-22, 2013, eds. K. Accetta, R. Fellinger, P. Lourenço Gonçalves, S. Musselwhite, and W. P. van Pelt, 201—216. Oxford and Philadelphia.

Walsh, C. 2016. The Transmission of Courtly Lifestyles in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. PhD diss., University College London.

Weeden, M. 2018. “Hittite-Ahhiyawan Politics as Seen from the Tablets: A Reaction to Trevor Bryce’s Article from a Hittitological Perspective.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 4:217—227.

Yasur-Landau, A. 2005. “Mycenaean, Hittite and Mesopotamian tables ‘with nine feet’.” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici 47:299—307.

Zaccagnini, C. 1999. “Aspetti della diplomazia nel Vicino Oriente antico (XIV-XIII secolo a.C.).” Studi Storici 40/1:181—217.

[1] Recently Aḫḫiyawa was identified with Chios (Egetmeyer 2022).

[2] PY Ta 711, PY Ta 709, PY Ta 641, PY Ta 716, PY Ta 642, PY Ta 713 PY Ta 715, PY Ta 714, PY Ta 708, PY Ta 707, PY Ta 722 PY Ta 721, and PY Ta 710.

[3] As for the number and type of seats, see Palaima 2004:115; Varias 2016:553—554. Differently, Shelmerdine 2012:686; Tsagrakis 2012:326—327; Archives; Pierini 2021:116.

[4] As for the wood, see Pierini 2021:115.

[5] Pierini recently proposed the meaning ‘spring type’ referring to tables and chairs (Pierini 2021:121—124).

[6] ‘Made of ivory’ or ‘covered with ivory plaques’ (Luján and Bernabé 2012:627).

[7] As lapis lazuli, DMic s.v.; Tsagrakis 2012.

[8] As ‘onager’s head’, see Hart 1993.

[9] DMic s.v. On the possible phonetic values of *34 see Judson 2020, 128—135, with quoted bibliography.

[10] Further texts are KBo 18.168 and KBo 18.186. Košak 1982:54—56, 153, 169—170, 184—185, 192; Siegelová 1986:56—59, 378—379, 489, 510—513, 529—530; Burgin 2022b:449—451, 516—518, 534—536, 565—568.

[11] Definition based on Koehl 2013:240–243.

[12] Further texts are KUB 38.20, KUB 42.67, KBo 18.159, KBo 23.26+, KUB 42.42, KUB 42.19, KUB 12.1, KBo 18.153(+)–KUB 26.66(+), KUB 42.10+, KBo 18.178, Bo 9184, KUB 40.95, KBo 2.11, KBo 31.54, KUB 42.61, KBo 71.46, DBH 46/2.150, KBo 18.170(+)–KUB 42.43, KBo 55.5, KBo 18.176, KUB 42.106, KUB 42.57, KBo 13.239, and KBo 18.181. For all, see Beckman et al. 2011:176—182; Singer 2011:461—466; Burgin 2022b: 58—60, 129—143, 151—162, 241—247, 253—259, 261—265, 410—414, 455—457, 483—484, with previous editions (Kempinski and Košak 1977:89—90; Mascheroni 1979; Košak 1982; Siegelová 1986).

[13] In addition to the texts in Figures 3—4: DBH 42/2.73, KBo 9.92, KBo 14.72, KBo 18.161–KUB 42.80, KBo 60.10, KBo 67.104, KBo 67.289, KUB 38.11, KUB 42.32, KUB 42.33+, KUB 42.38, KUB 42.58, KUB 42.59, KUB 42.64, KUB 42.70, KUB 42.75, KUB 42.78, KUB 60.71, and VBoT 62.

[14] For instance, the Ivory Houses at Mycenae (Tournavitou 1995).

[15] On the diplomatic gift-exchanges involving the Mycenaeans, see Killen 2008:181—189; Kelder 2012:50; Bennet and Halstead 2014:278—279; Kelder 2018:205—206. On the shared use of vessels in diplomatic ceremonies see Walsh 2016:85—86.

[16] Feldman describes a similar process for Ugarit (Feldman 2006:18–19).

For a discussion of this and the other ECRs’ papers, go the MASt Summer 2024 report landing page and scroll to §166