How to kill a snake (with a sherd): New approaches to administrative ostraka in 1st millennium BCE Cyprus and the Minoan Snake Goddess.

Paper and Summary of the Discussion held at the Spring 2024 MASt Seminar (Friday, April 12)

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Spring 2024 session of the MASt seminars by welcoming the participants to the April meeting and sharing some great news about some MASt’s members recent achievements.

§2. MASt editorial assistant Linda Rocchi has been awarded a Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellowship. Massive congratulations dear Linda!

§3. MASt secretary Giulia Muti has received the Seal of Excellence from the same grant scheme, namely the Marie Skłodowska Curie Fellowship. A lot of very well-deserved congratulations, dear Giulia!

§4. MASt editorial assistant Katarzyna Żebrowska has obtained her PhD title in archaeology. You rock dear Kasia, congratulations!

§5. MASt steady member Janice Crowley has published the book she presented during the Summer 2023 MASt seminar, titled ICON: Art and Meaning in Aegean Seal Images. Huge congratulations dear Janice!

§6. The Spring 2024 MASt seminar featured Artemis Karnava and Nicoletta Momigliano as speakers.

§7. Artemis Karnava talked about “Administrative ostraka in Cyprus during the 1st millennium BCE”. Her paper, which will be published in full in a future report, focused on inscribed sherds with Cypriot syllabic texts of administrative character dating to the first millennium BCE that have been discovered on the island of Cyprus.

§8. The chronology of these Cypriot documents spans over three centuries since the earliest evidence seems to date to the sixth century BCE and, despite the syllabary surviving as late as the third century, the latest administrative evidence comes from the later of part of the fourth century BCE.

§9. In her talk, Karnava provided an overview of the available inscribed sherds with Cypriot syllabic texts of administrative character and explored their purpose and role in the overall Cypriot social circumstances of the period.

§10. Nicoletta Momigliano gave a presentation titled “The Many Lives of a Snake Goddess: Diachronic, Multicultural, and Multisensory Perspectives” (henceforth MLSG), centered on a collaborative and interdisciplinary project with the same title involving the University of Bristol, Trinity College Dublin, King’s College London, the Ashmolean Museum, the British School at Athens, and the Heraklion Museum as well as several artists and writers.

§11. The MLSG project focuses on two of the most iconic finds from Minoan Crete. Specifically, the figurines of the “Snake goddess” and her “votary” discovered by Arthur Evans during the 1903 campaign of his excavations at Knossos.

§12. Ever since, the figurines have beguiled not only archaeologists and other scholars concerned with past worlds, but also modern artists, writers, psychoanalysts, feminists, fashion designers, and followers of modern Paganism, among many others—all of whom have re-imagined these objects for their own purposes.

§13. However, despite their iconic status, the figurines pose several issues, a neglected area that Momigliano and her team are tackling in their current project by addressing challenges such as understanding their original appearance in Minoan times, their significance, and how they have been perceived and reimagined beyond archaeology.

§14. In her MASt talk, Momigliano provided insights into how her collaborative project explores these issues and examines the public’s interaction with these figurines and the modern creations they have inspired. The MLSG project operates a 3-pronged tactic based on archaeology, reception studies, and a multi-sensory approach, all in dialogue with each other, and involving engagement with writers, artists, herpetologists, specialists in access strategies, among others.

§15. In addition to the MASt board members (Editor-in-Chief: Rachele Pierini; Associate Editor: Tom Palaima; Editorial committee members: Elena Džukeska, Joseph Maran, Leonard Muellner, Gregory Nagy, Marie Louise Nosch, Thomas Olander, Birgit Olsen, Helena Tomas, Agata Ulanowska, Roger Woodard; Secretary: Giulia Muti; Editorial Assistants: Harriet Cliffen, Linda Rocchi, Katarzyna Żebrowska; Student Assistant: Matilda Agdler), roughly 75 attendees took part in the Spring 2024 MASt seminar, among whom Ellen Adams, Maria Giulia Amadasi Guzzo, Maria Anastasiadou, Eric H. Cline, Stephen Colvin, J. L. García Ramón, Benjamin Huber, Maria Iacovou, Bernice Jones, Artemis Karnava, Elisabeth Keyser, Ido Koch, Daniel Kölligan, Martin J. Kümmel, Hedvig Landenius Enegren, Olga Levaniouk, Matteo Macciò, Nicoletta Momigliano, Christine Morris, Sarah Morris, Dimitri Nakassis, Massimo Perna, Vassiliki Pliatsika, Mnemosyne Rice, Ester Salgarella, Matthew Scarborough, Andrew Shapland, Morena Stefanova, Malcolm H. Wiener, Assaf Yasur-Landau, José Ángel Zámora López.

§16. Substantial discussions followed both presentations. Specifically, contributions to the seminar were made by Maria Iacovou (see below at §55), Bernice Jones (§§63—65; 67; 78; 80; 86; 88; 93), Artemis Karnava (§§42; 44; 48—49; 52; 56; 58; 60; 99—100), Nicoletta Momigliano (§§66; 68; 72; 75—77; 79; 82; 84—85; 87; 96; 101), Greg Nagy (§62), Tom Palaima (§§50—51; 53; 59; 61; 92; 94—95; 97—98), Massimo Perna (§§45—47), Rachele Pierini (§§89—91), Vassiliki Pliatsika (§§73—74; 76; 81), Andrew Shapland (§§69—71), Roger Woodard (§§41.2—41.2; 43; 54; 57; 83).

The Many lives of a Snake Goddess: Diachronic, Multicultural, and Multisensory Perspectives

Presenter: Nicoletta Momigliano

§17. Nicoletta Momigliano, on behalf of her colleagues, presented a seminar on their new collaborative and interdisciplinary project titled “The Many Lives of a Snake Goddess: Diachronic, Multicultural, and Multisensory Perspectives”.

§18. The project is spearheaded by Ellen Adams, Christine Morris, and Nicoletta Momigliano, in collaboration with colleagues from museums and other research institutions (Katerina Athanasaki, Heraklion Museum; Kostis Christakis Knossos Research Centre, British School at Athens; Andrew Shapland, Ashmolean Museum), Doctoral students, writers, artists, herpetologists, musicians, and many other specialists (see §39. Appendix).

§19. Why have we chosen to create a new project focusing on these well-known objects and what are we trying to do? The figurines are among the most iconic finds from Minoan Crete. Ever since their discovery in 1903 (Evans 1903:74–87), they have fascinated not only archaeologists and other scholars concerned with the past, but also modern artists, writers, fashion designers, and followers of modern Paganism, among many others—all of whom have reused and reimagined these objects for their own purposes and have given them new lives, so to speak. The figurine that Evans dubbed the “votary” has become a poster girl for Minoan Crete, since it is her image that is most often reproduced in a wide variety of media: she even took pride of place in the “Clepsydra”, the parade of Greek history at the opening ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympics (see e.g. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YYvnvr8Cpzo, from 22’57’’ to 23’08’’; Boze 2016:2, figure 3).

§20. And yet, despite their iconic status, many people do not realize that the figurines are problematic in many respects. Issues involve both their ancient and modern lives and can be encapsulated in these three broad questions:

- How have they been reconstructed, both physically and interpretatively? (To put it in other words: what did they really look like originally? What did they signify?)

- How have they been reimagined and recreated beyond archaeology since their discovery?

- How have they been described to, as well as perceived and appreciated by the general public?

These three questions can also be broken down into many other separate, more specific queries, such as: How accurate are their reconstructions? What ideas about the female body do they convey? How can we enhance the appreciation of these objects for the public, including people with sensory impairments?

§21. All these and other issues resonate with aspects of our past and current research, and so we decided to join forces and create this research project, which involves a three-pronged tactic based on elements from archaeology, reception studies, and a multi-sensory approach—all in dialogue with each other. In this seminar it is not possible to discuss all these questions and aspects in detail, so the focus will be on elements of our work so far, that are relevant to the reconstructions, modern reimaginings, and multisensory approach.

§22. First, however, it may be useful to provide a brief reminder about the discovery of these iconic objects. Evans unearthed the figurines during the 1903 excavation campaign at Knossos (Evans 1903:74–87). They were found broken and incomplete inside two receptacles or cists, which Evans dubbed the “Temple Repositories”. The cists were hidden under a paved floor, in the West wing of the palace and contained fragments of another 3 or 4 similar figurines (so the figurines would have numbered at least 5 or 6 in total: cf. Panagiotaki 1993:57–59, figure 2; Panagiotaki 1999:96–104, and plates 16d and 16f). Besides the figurines’ fragments, the cists contained many other finds, such as dozens of clay vases, and other items including hundreds of shells, clay seal impressions, Linear A inscriptions, animal and fish bones, carbonized corn and wood, objects in marble and other precious or semi-precious materials as well as more objects made in faience.

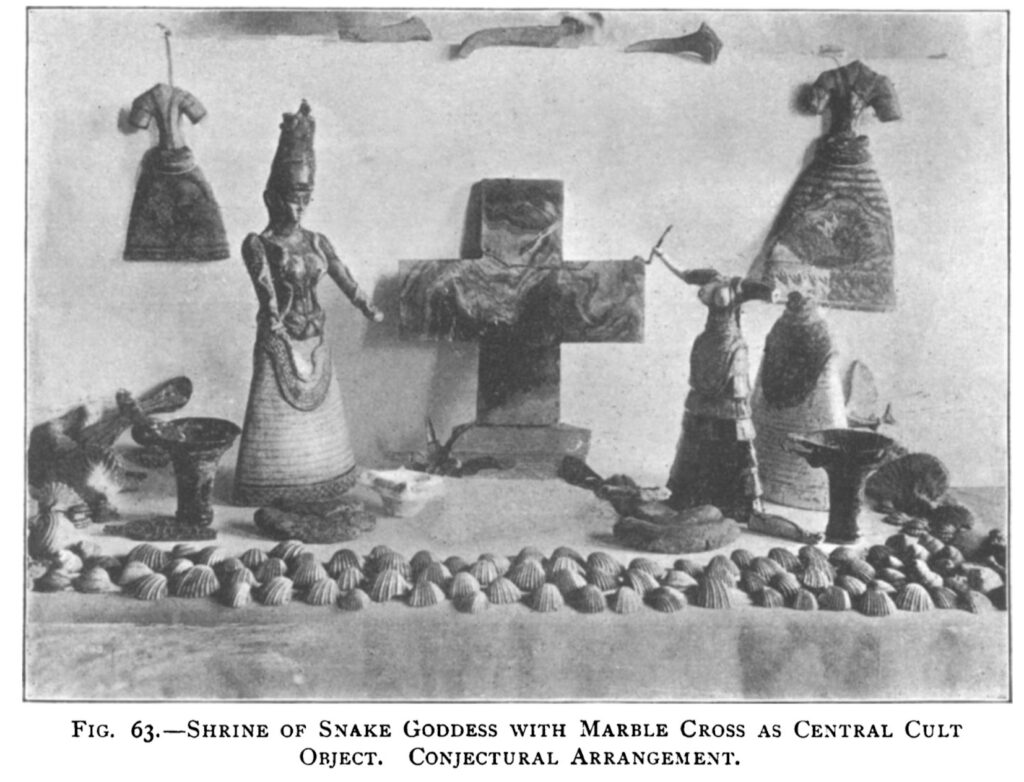

§23. The character of these finds, their careful placement inside the cists in separate layers, in a kind of structured deposition (cf. Hatzaki 2009), all suggested that these were objects that required special disposal and thus could have come from a shrine. This is why Evans dubbed the cists the “Temple Repositories”. Figure 1 (after Evans 1903: figure 63) shows how Evans used a selection of finds to illustrate how he thought the shrine might have been arranged.

Figure 1. Evans’s hypothetical reconstruction of the shrine of the “Snake-Goddess” (after Evans 1903: figure 63).

Figure 1. Evans’s hypothetical reconstruction of the shrine of the “Snake-Goddess” (after Evans 1903: figure 63).

§24.1. As already mentioned, Evans discovered fragments belonging to a total of 5 or 6 figurines, but only two were fully reconstructed: one that he called the “goddess”, because of her larger size and headgear, and the other, slightly smaller, that he called the “votary” (Evans 1903:74–87). A Danish artist, Halvor Bagge, who worked at Knossos between 1902 and 1905, reconstructed them in two stages. The first was immediately after their discovery in 1903, as can be gathered from photographs and drawings published at that time (cf. Figures 2 and 3, after Evans 1903: figures 56 and 57).

Figure 2. Photograph of “votary” after first stage of reconstruction by Halvor Bagge (after Evans 1903: figure 56).

Figure 3. Drawing of “votary” showing reconstructed parts in lighter shade (after Evans 1903: figure 67).

§24.2. These show the “votary” still without her head and left arm, but with the lower part of the item clenched in her right fist already reconstructed as a snake (see also Evans 1903:78 with notes 2 and 3 about restorations). Like Figure 3, two unpublished drawings made around 1903, kept in the Evans Archive of the Ashmolean Museum, show the original pieces in darker shades and also illustrate a rather different reconstruction of the “votary”, based more closely on the larger figurine. In the second stage of the reconstructions, which occurred between 1903 and 1905, Bagge restored the left arm and snake of the “votary” and her head. He also placed on top of her entirely reconstructed head two original Minoan fragments: a piece of headgear and an animal that looks like a cat (Figure 4).

Figure 4. The “goddess” and “votary” as they appear today in the Heraklion Museum after second stage of reconstruction by Bagge (photo: N. Momigliano).

§24.3. Since Bagge’s reconstructions were never fully documented, it is by no means certain that the headgear and the cat-like creature belong together, let alone that they both belong to the “votary”, since her head is entirely modern. At some point between 1903 and 1905, Bagge also created the replicas that are now on display in the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, which have now become historic artefacts in their own right (see https://collections.ashmolean.org/object/561573). One could easily spend some time playing a game of spot the difference between reconstructed originals and replicas (e.g. different positions of the cat-like creature on top of the “votary’s” reconstructed head in the Heraklion and Ashmolean pieces).

§25. To summarize what has been discussed so far about the reconstructions, there are considerable doubts regarding the “votary” from the base of her neck up. In addition, MacGillivray and Bonney have suggested that the much-restored item held in the votary’s right hand (and, by symmetry, in her left hand) is not a snake (but possibly twine or rope), because of its stripy appearance, which is not snake-like and looks quite different from that of the unmistakable snakes found on the “goddess” and on other fragments of arms belonging to other figurines, all of which present spotted (not stripy) skin marks (MacGillivray 2000:223; Bonney 2011:178; see also Jones 2016).

§26. Bonney also noted that the stripy or segmented appearance of the item clinched by the “votary” recalls that of garlands and ropes that one finds on the finial of a pin from the Shaft Graves at Mycenae and in many Old Syrian cylinder seals showing a goddess opening her skirt (Bonney 2011:177–181, figures 8 and 10). Partly based on Bonney’s suggestions as well as other evidence, Bernice Jones (forthcoming: figure 16) has recently proposed an alternative reconstruction of the “votary” (Figure 5). Her reconstruction considers the original segment clenched in the votary’s hand to be shorter than suggested by Evans and Bagge (cf. further discussion of segment in §29 below).

Figure 5. Bernice Jones’s alternative reconstruction of the “votary” (after Jones forthcoming; photo courtesy of Bernice Jones).

§27. Intrigued by the remarks and reconstructions made by MacGillivray, Bonney, and Jones, we looked again at the figurines and their restorations. We commissioned the archaeologist and artist Céline Murphy to create similar reconstructions of the votary (Figures 6, 7, 8). We used drawings instead of photographs (cf. Figure 5) because these seemed to us to allow a clearer distinction between original fragments and reconstructions. In the course of our work, we noticed that segmented or striped ropes, as part of female garments, also appeared in the well-known fresco of a young woman with wounded foot from Xeste 3 at the site of Akrotiri on Thera (Doumas 1992: figure 105) and on some Minoan clay figurines in the Heraklion Museum. Moreover, we noticed that goat-horns sometimes present a stripy or segmented appearance when depicted in seals of the Neopalatial period, which often show female figures accompanied by these animals (see e.g. CMS II,6 030; CMS VS1A 175; CMS VS1A 369; CMS II,7 023; CMS VI 322; CMS XI 027).

Figure 6. MLSG commission: Céline Murphy’s reconstruction of the “votary” holding segmented rope, based on Jones forthcoming.

Figure 7. MLSG commission: Céline Murphy’s reconstruction of the “votary” holding two loose ropes, or rope-like strips of cloth, partly inspired by fresco of wounded woman in Xeste 3, Akrotiri.

Figure 8. MLSG commission: Céline Murphy’s reconstruction of the “votary” holding (goat) horns as shorthand (pars pro toto) of animal, partly inspired by imagery of Neopalatial sealings.

§28. Based on these observations, Céline Murphy has created for our project the reconstructions illustrated in Figures 6–8, with ropes and horns. Figure 6 is effectively based on Jones’s reconstruction (Figure 5); Figure 7 is largely inspired by the fresco from Akrotiri mentioned above; and Figure 8, showing the figuring holding goat-horns (as pars pro toto of the animal), is partly inspired by the imagery of women accompanied by goats found on Neopalatial seals.

§29. We also toyed with other potential reconstructions, like the one illustrated in the pencil sketch in Figure 9, which is partly based on Andrew Shapland’s thought-provoking suggestion that the so-called “Snake Frame” motif, which appears on Minoan seals, represents a bow made with horns from Cretan wild goats (personal communication; see also Shapland forthcoming). Although Shapland’s new interpretation of the “Snake Frame” motif is very intriguing, we decided, in the end, not to proceed beyond this pencil sketch for a possible reconstruction of the “votary”. This was largely for three reasons: first, in Minoan iconography the snake-frame/bow usually rests on the open palms of the female figure, whereas the votary is clenching the object in her fist; secondly, the original item in her hand, as shown in this photo and in an x-ray published by Walter Müller (2003:plate XXXVa), apparently stops with a rounded point. Thirdly, the object seems to be a bit too twisted to be part of a bow. One should note, however, that the upper segment of the object clenched by the “votary” appears to be composed of two fragments, i.e. there seems to be a join as indicated by the arrow in Figure 10. For this reason, Bernice Jones thought that the original fragment held in the right fist of the “votary” was shorter and that the rest was modern reconstruction or at least rather uncertain. She is probably right, but in defense of Evans and Bagge, one might say that they were very explicit about the restoration of the lower part of the item as part of the body and head of a snake (cf. above and Evans 1903:78 with note 3), whereas they implied that the upper part was all authentic. If Bernice Jones is correct, and the original object held by the “votary” is much shorter, and broken, then there are more possibilities regarding its reconstruction (including Shapland’s suggestion that it could be part of a bow). But if Evans and Bagge did not add the top part (or added it correctly), the possibilities for alternative reconstructions are reduced. For the time being, until anyone is allowed to study this item more closely (and perhaps perform some analyses), we decided to give Evans and Bagge the benefit of the doubt and treat the whole of the upper part of the segment in the votary’s right hand as original.

Figure 9. MLSG commission: Céline Murphy’s pencil sketch of potential reconstruction of “votary” holding a bow made of goat horns in a pose similar to “snake frame” iconography (after A. Shapland’s suggestion).

Figure 10. Detail of stripy item held in the right hand of “votary” (photo: N. Momigliano).

§30. In any case, given all the uncertainties, it is impossible to say at present which of these reconstructions is more accurate and, perhaps, we should not categorically exclude that the so-called votary held snakes in her hands. We can be sure that the “goddess” is covered with snakes with spotted skins, which are reminiscent of two of the indigenous Cretan species, namely the European rat snake or leopard snake (Zamenis situla) and the European cat snake (Telescopus fallax).[1] There are no stripy snakes on Crete, but perhaps the artisan wanted to show the “votary” as holding different snakes or perceived the skin markings on the wriggling snakes as stripes rather than spots, for, after all, the so-called naturalism of Minoan iconography often gives the essence of an object without being necessarily very accurate. Probably we shall never know.

§31. Nevertheless, the most important elements that have emerged from our engagement with the reconstructions are that 1) the devil is in the detail; 2) more analyses (macroscopic and microscopic) of these objects would be useful; and 3) (last but not least) one should never take for granted that even the most familiar and iconic Minoan objects are fixed entities never to be questioned, and we believe that the public should be made aware of these uncertainties, rather than be encouraged to believe in cliché narratives about both figurines being images of the great Minoan mother goddess in her chthonic aspect. The past is always reconstructed from fragments, and even if our reconstructions of the votary are not accurate, at least they have been very “good to think with” and made us reflect about different interpretations regarding the figurines’ symbolism in Minoan times.

§32. It is, however, beyond the aims of this paper to dwell on the interpretations of what the figurines signified in the Bronze Age. Instead, other aspects of our project—namely our work on modern reimagining’s and multi-sensory approaches—are briefly discussed below. They are also very good to think with.

§33. As hinted earlier, one of the aims of our project is to examine the impact of the figurines beyond archaeology, and this involves the documentation and contextualization of the diverse reuses and reimaginings of the figurines in different cultural practices. We have collected over 300 hundred examples so far, spanning over a century and many different countries, as well as a wide variety of media. Today we can show you only a few examples, which come from Greece and different decades of the 21st century. One is from the opening ceremony of the 2004 Athens Olympics (cf. above §19.), designed by Dimitris Papaioannou, where the use of the “votary” is interesting for a variety of reasons, ranging from the incorporation of the non-Greek Minoans in the long continuum of Greek history (whereas the Romans and the Ottomans were excluded: cf. Momigliano 2020:237), to the strong erotic emphasis given to the “votary”, which led to numerous complaints by prudish elements among the television spectators (Morris 2009:243). The other is an image by the designer Kostas Bekiaris, created for the Facebook page of No Budget Epics (ca. 2019) (Figure 11). This is also linked to the sexualization of the Minoan figurine, but here the “votary” is strangling the two snakes because she is fed up with their typical male sexist remarks, and this is to indicate the artist’s belief that women have the right to dress and behave as they like without being sexualized by men (K. Bekiaris, personal communication).

Figure 11. Image created by Greek designer Kostas Bekiaris (ca. 2019) for the Facebook pages of “No Budget Epics” (reproduced courtesy of Kostas Bekiaris).

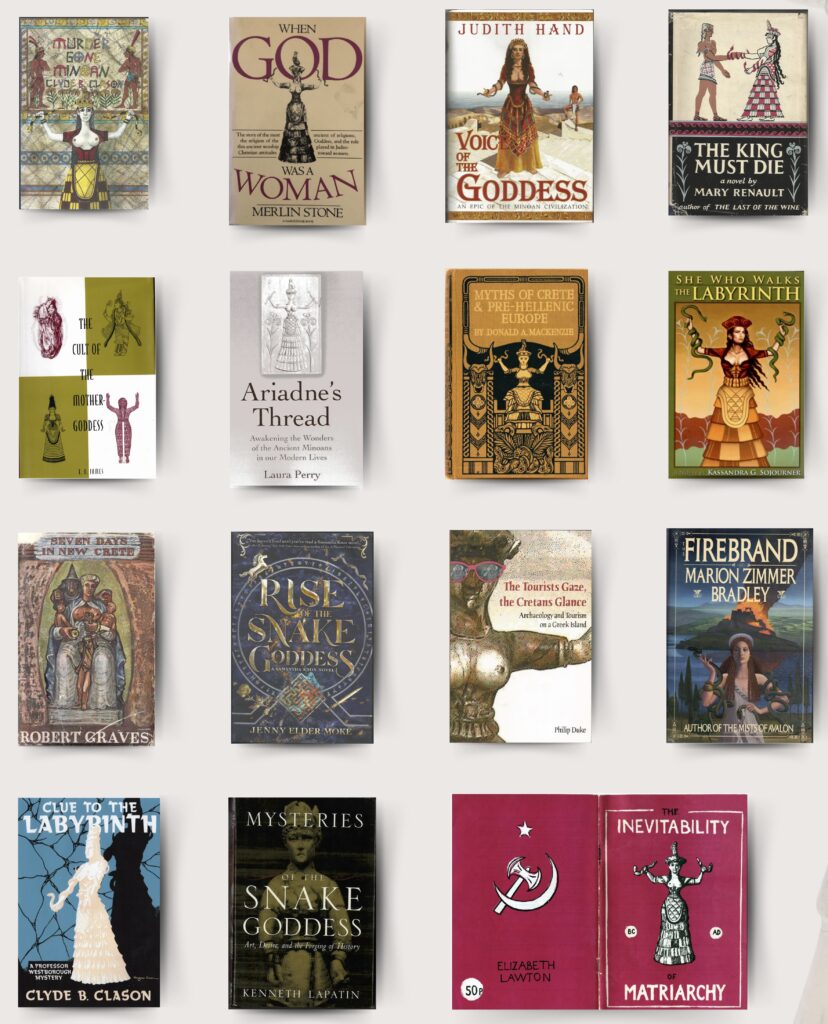

§34. Many other examples of modern reimaginings come from the field of literature, where the figurines appear in works of every genre one can think of—from pulp fiction to political pamphlets (Figure 12). Many examples come from poetry. The earliest poem that we have identified so far is “Minoan Porcelain”, published in 1917 by Aldous Huxley, the author of Brave New World (Momigliano 2020:119). Most recently, as part of our multisensory approach, our project commissioned award-winning British author and poet Ruth Padel to compose new poems inspired by the figurines. One of her poems was included in the audio-recordings that accompanied the splendid exhibition Labyrinth: Knossos, Myth and Reality curated by Andrew Shapland at the Ashmolean Museum in 2023, which included Bagge’s replicas of the snake goddess figurines.

Figure 12. Examples of books in English language, covering different genres (from pulp fiction to political pamphlets), the covers of which prominently display modern reimaginings of the snake goddess figurines (image created for the MLSG project by Sarah Lidwell Durning).

§35. The use of audio-recordings in this exhibition is a reminder of the importance of synesthesia as a strategy for enhancing the museum experience of visitors (see, e.g., Levent and Pascual-Leone 2014; see also, e.g., the experience of the people who toured the Jorvik Viking Centre over the last three decades: https://www.jorvikvikingcentre.co.uk/ and https://www.jorvikvikingcentre.co.uk/press/norse-ty-niffs-historic-aroma-packages-trialled-bring-vikings-smells-home/). This brings us to the third aspect of our project, our multisensory approach.

§36. Besides the new poems by Ruth Padel, we have commissioned other works, and this part of our research is closely linked to the MANSIL project led by Ellen Adams (Museum Access Network for Sensory Impairments, based in London, https://mansil.uk/). Other commissions by the MLSG project so far include:

- Audio descriptions of the figurines for blind or partially sighted people.

- A piece on “mindful looking” which applies “mindfulness technique” to the figurines.

- As we are keen to give voice and agency to people with sensory impairments, we commissioned partially sighted writer Tanvir Bush, who has retinitis pigmentosa, to share her reflections on her encounters with the figurines. Her texts describe her experience of handling replicas and explore the process of piecing together meaning from the fragments that her condition allows her to see (something that recalls what archaeologists do).

- Since our research involves exploring different modes of communication about archaeological objects, we have commissioned deaf actor Zoë McWhinney to create videos describing the discovery and reconstructions of the figurines, as well as translating two of Padel’s poems into British Sign Language. This is to compare how people can engage with the figurines using a visual-spatial language, in contrast with linear spoken English.

- In July 2024 there will be an event at the Knossos Research Centre of BSA, where some Cretan artists will present new works inspired by the figurines, and these will include visual art and Cretan μαντινάδες[2].

Although some of these works were commissioned for the benefit of people with sensory impairments above all, we believe that everybody can benefit from these.

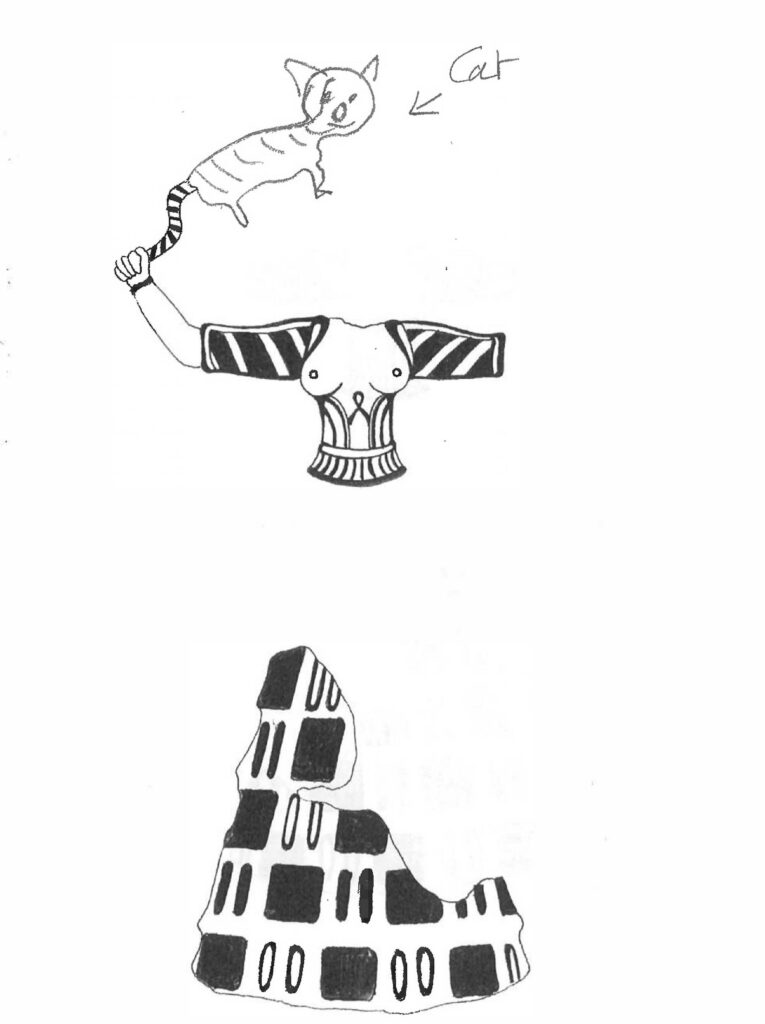

§37. Indeed, under the lead of Ellen Adams, our project has conducted several surveys to assess the impact that audio descriptions and other commissioned works also have on people who do not have sensory impairments. In addition to this, at a recent event held in Dublin we have explored the public’s reactions to different reconstructions of the “votary” and encouraged people to offer their own suggestions. There were many interesting suggestions: our favorite is the votary swinging a cat (Figure 13), but many people really liked the idea of the votary holding something over her head, like the so-called Snake-Frame iconography, as illustrated in the example in Figure 14.

Figure 13. Ironic alternative reconstruction of the “votary” created by a member of the public attending a MLSG event held at Trinity College Dublin in 2024.

Figure 14. Another alternative reconstruction of the “votary” created by a member of the public attending a MLSG event held at Trinity College Dublin in 2024.

§38. To sum up and conclude, nowadays millions of people have encountered the snake-goddess figurines in the Heraklion Museum and their images in other media. Yet, despite their iconic status, many aspects of the figurines’ ancient and modern lives remain obscure. Our project aims to provide an overview of the current state of knowledge (and disagreements) regarding these figurines. In particular, we wish to enhance the public’s appreciation of these objects and illustrate their complex lives using a variety of methodologies and approaches. All this places our research at the interface between archaeology, the creative arts, and museum studies and by using these figurines as a case study, we also hope to address important and broader questions relevant to the production of knowledge, dissemination, and uses of the past in our society.

§39. Appendix: list of contributors to the project so far (April 2024)

Karly Allen (art lecturer and museum educator, Limina Collective https://www.liminacollective.com/)

Tanvir Bush (writer, film-maker, and photographer, https://tanvirbush.com/about/)

Petros Lymberakis (herpetologist, University of Crete)

Sarah Lidwell Durnin (PhD student, Bristol)

Kalia Lyraki (singer and musician, https://kalialyraki.com/)

Zoë McWhinney (actress, poet, theatre maker, Visual Vernacular artist)

Céline Murphy (archaeologist and artist, https://celinemurphy88.wordpress.com/)

Ruth Padel (writer, https://www.ruthpadel.com/)

Roussetos Panagiotakis (artist)

Daniel Peatfield (IT consultant)

Mnemosyne Rice (PhD student, Trinity College Dublin)

Mina Trikali (Library and Photographic Archive, Museum of Natural History of Crete)

Teresa Valavani (psychologist and artist)

Lucia Van der Drift (teacher and writer in meditation, mindfulness, and Buddhism, Limina Collective https://www.liminacollective.com/)

§40. Momigliano’s Bibliography

Bonney, E. M. 2011. “Disarming the Snake Goddess: a reconsideration of the faience figurines from the Temple Repositories at Knossos.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 24(2):71–190.

Boze, D. 2016. “Creating history by re-creating the Minoan Snake Goddess.” The Journal of Art Historiography 15. Available at: https://arthistoriography.wordpress.com/15-dec16/ and https://arthistoriography.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/boze.pdf.

Doumas, C. 1992. The Wall Paintings of Thera. Athens.

Evans, A. J. 1903. “The palace of Knossos. Provisional report for the year 1903.” Annual of the British School at Athens 9:1–153.

Hatzaki, E. 2009. “Structured deposition as ritual action at Knossos.” In Archaeologies of Cult: Essays on Ritual and Cult in Crete in Honor of Geraldine C. Gesell, ed. A. L. D’Agata and A. Van de Moortel, 19–30. Hesperia Supplement 42.

Jones, B. R. 2016. “The Three Minoan ‘Snake Goddesses’.” In Studies in Aegean Art and Culture: A New York Aegean Bronze Age Colloquium in Memory of Ellen N. Davis, ed. R. Koehl, 93—112. Philadelphia.

Jones, B. R. forthcoming. “The iconography of the Knossos Snake Goddess based on their gestures, stances, movements and attributes”. In Gesture–Stance–Movement. Communicating Bodies in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of a Conference at Heidelberg, 11–13 November 2021, ed. U. Günkel-Maschek, C. Murphy, F. Blakolmer, and D. Panagiotopoulos, 243–257..

Levent, N. S. and A. Pascual-Leone, ed. 2014. The Multisensory Museum: Cross-disciplinary Perspectives on Touch, Sound, Smell, Memory, and Space. Lanham.

MacGillivray, J. A. 2000. Minotaur: Sir Arthur Evans and the Archaeology of the Minoan Myth. New York.

Momigliano, N. 2020. In Search of the Labyrinth: The Cultural Legacy of Minoan Crete. London.

Morris, C. 2009. “The iconography of the bared breast in Aegean Bronze Age art.” In Fylo: Engendering Prehistoric ‘Stratigraphies’ in the Aegean and the Mediterranean. Proceedings of an International Conference, University of Crete, Rethymno 2–5 June 2005, ed. K. Kopaka, 243–249. Aegaeum 30. Liège and Austin.

Müller, W. 2003. “Minoan works of art seen with penetrating eyes: X-ray testing of gold, pottery and faience.” In Metron: Measuring the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 9th International Aegean Conference/9e Rencontre égéenne internationale, New Haven, Yale University, 18–21 April 2002, ed. K. Polinger-Foster and R. Laffineur, 147–154. Aegaeum 24. Liège and Austin.

Panagiotaki, M. 1993. “The Temple Repositories of Knossos: new information from the unpublished notes of Sir Arthur Evans.” Annual of the British School at Athens 88:49–91.

Panagiotaki, M. 1999. The Central Palace Sanctuary at Knossos. British School at Athens Supplementary Volume 31. London.

Shapland, A. forthcoming. “Tentacular thinking in Bronze Age Crete”. In Ontologies in the Making: Anthropological and Archaeological Perspectives.

Discussion following Karnava and Momigliano’s talks

§41.1. Roger Woodard opened the discussion by mentioning Assyrian ostraca and remarking that we do not possess much evidence for the Assyrian use of ostraca. Yet, it has been speculated that ostraka were probably much more widely used in the Neo-Assyrian Empire than has been traditionally thought, Woodard added.

§41.2. Woodard reflected that one really good example of an ostrakon that we possess from the Neo-Assyrian period is dated to the seventh century. In light of this, he asked whether anyone has speculated that the introduction of ostraka into Cyprus may have had an Assyrian connection.

§42. Artemis Karnava replied that, unfortunately, we do not possess a wealth of material in the 6th century BCE, when the practice seems to be coming over. Nevertheless, the Assyrian administration seems to be a good precedent for the use of this practice, Karnava noted.

§43. Woodard continued by remarking that the semitists processing this material tend to think that the material is Phoenician, and so he asked whether there is any indication that Aramaic could be involved.

§44. Karnava was hesitant about the involvement of Aramaic, and both she and Woodard agreed that there exists a distinction that, fine as it might be, is a real distinction.

§45. Massimo Perna remarked that the ostraka shown by Karnava remind us of the Cypro-Minoan tradition. He noted that we possess a very famous ostrakon, which is the only document of economic nature, presenting figures and ideograms. Perna argued that this artifact demonstrates that there is a Cypriot tradition connected to the autochthonous tradition of the second millennium BCE.

§46. Perna added that the lack of actual accounting documents and, conversely, the preservation of ostraka from the first and second millennium BCE is probably due to a trivial reason, namely, that ostraka are not perishable, differently from other perishable documents that must have been used.

§47. This, Perna continued, is very different from the Phoenician scenario since there is a high number of Phoenician economic documents but this is not the case for the Cypriot material. A possible explanation for the small number Cypriot documents might be that they were recapitulated on parchment, which was not the case for the Phoenician documents, Perna concluded.

§48. Karnava agreed with Perna on the existence of a local tradition, demonstrated by the existence of an ostrakon in Cypro-Minoan dating to the second millennium BCE. However—Karnava warned—this does not necessarily mean that there is continuity, even if a tradition is present. Of course, she continued, the writing system at play in the first millennium BCE follows the Cypro-Minoan writing system, even though there is an interval during which writing practices cannot be tracked. To conclude this excursus, Karnava agreed with Perna that it is important also to look at earlier evidence.

§49. Regarding the comparison with the Phoenicians, Karnava noted that the small amount of ostraka might also be a matter of chance. By way of example, she mentioned the case of Idalion, a Phoenician polity that has been extensively excavated, and added that the same goes for Kition. However, numbers might not be the key point since even only one or two ostraka might be indicative for thousands, Karnava concluded.

§50. Tom Palaima questioned the necessity to introduce ostraka from other cultures. In his opinion, the notion is problematic, because it is very natural to write on broken clay—that is, it is natural to use something that would otherwise be no longer useful. In that case, the only thing that is needed is a sharp implement to incise or some pigmented liquid to paint, Palaima noted. Therefore, he remarked, it is possible that there may be an economic factor at play, such as access to a metallic implement that can function as a stylus or to a pot of painted liquid.

§51. Moreover, there could be other practical factors such as how long a pot of pigmented liquid can last if sealed properly, Palaima added. Even allowing for these factors, the practice seems to be very natural, Palaima continued. Thus, it may be necessary to think about direct administrative contact with another culture, from which the practice might have been borrowed, but it may also be possible to look at the diffusion of ideas, and in particular the idea of writing, Palaima stressed. Therefore, he concluded, we must really posit that the Phoenicians, the Neo-Assyrians, and the Greeks might have borrowed the practice from the Eteocypriots—but writing on broken pottery would seem a natural practice to develop internally.

§52. Karnava agreed on this point, adding that she would like to know what the internal necessity was. She remarked that, while the practice does not need to be imported, it would be important to think about the reasons why the practice itself arose.

§53. Palaima added that another element to consider is the extremely narrow application of literacy in the Mycenaean period—an element that really stands out in comparison with other cultures. To this, we should add other possible economic or political factors, Palaima concluded.

§54. Woodard noted that the introduction of ostraka could be another example of idea diffusion of the type Palaima studied. He added that we know there was a Cypriot presence among the armies of the Neo-Assyrians. Therefore, this could be taken as a starting point from which that idea could diffuse to Cyprus, Woodard concluded.

§55. Maria Iacovou remarked that, according to scholars now in Nicosia working on the Idalion archive, Idalion was not a Phoenician polity. It was using the Greek syllabary and issuing coins with the kings’ signatures in the syllabary until the Kition kings attacked and occupied the citadel of Idalion ca. mid-fiftth century BCE, Iacovou noted.

§56. Karnava noted that the administrative evidence does not tell us what people actually spoke, but it might nevertheless be a misuse of the term to speak about a Phoenician polity. She concluded by agreeing with Iacovou and adding that the administration could very well be a separate thing than the rest of the population.

§57. Woodard added that the exact same process can be seen for the Neo-Assyrian empire since Neo-Assyrians were writing in Aramaic while speaking Accadian. Thus, Aramaic was simply the official language of the administration, he stressed. Therefore, Woodard concluded, it is possible to imagine that for some Cypriot administrative unit in some place the Phoenician language could have become an administrative language.

§58. Karnava agreed with Woodard and added that she had this thought in mind at the beginning of her work. She added that the only image that we get of this population is through epigraphy, but we cannot be sure that the epigraphical habits are representative of all the population trends. Nevertheless, it is important to consider, in the first place, the languages that were used and the languages that are actually attested, Karnava concluded.

§59. Palaima asked about the practice of ostracism more in general: Did other Greek poleis ever adopt the practice of ostracism as it was practiced in Athens?

§60. Karnava replied that she does not think that this is the case. She added that, oddly, the debate tends to concentrate on the beginning of the practice (when exactly does it start? When does it take place for the first time? How many times did it take place?). Moreover, there are questions about its effects and about how it died out, Karnava continued. Nevertheless, she added, the practice does not seem to be found outside of Athens and seems, in a way, an Athenian “oddity”. As for the beginning of the practice, it is of course very hard to investigate, Karnava noted.

§61. Palaima added that it is important to consider some of the ostraka from the agora, which show that some of these ostraka were being mass-produced. This might mean that we need to downscale the literacy rate for Athens to something around 10%—not considering the amount of people who might have had simply “name literacy” (that is, who were able to write their name and nothing else). Therefore, he continued, we need to consider the degree to which it was necessary to know how to write in order to function in the society. These questions, he concluded, are also going to be extremely relevant to Karnava’s exciting work.

§62. Gregory Nagy added two parallels about writing practices. Specifically, his piece A Minoan-Mycenaean scribal legacy for converting rough copies into fair copies and his piece Echoes of a Minoan-Mycenaean scribal legacy in a story told by Herodotus.

§63. Bernice Jones thanked Momigliano for including some of her most recent research in her talk (forthcoming). Jones explained how, in her work, she approached the relevant iconographic motifs as both snakes and ropes, following the evidence behind the interpretations of Arthur Evans, Sandy MacGillivray, and Emily Bonney Miller.

§64. Jones further highlighted the extreme similarities between the Shaft Grave pin figurine from Mycenae and the Snake Goddess, apart from the apron, further pointing out her identification of ropes held on the former. She further connected these ropes with the presence of what Karo identified as papyrus paraphernalia on the figurine’s head.

§65. Considering the recently recovered evidence from Egypt, that proves the use of papyrus in rope making, and the extensive association of the latter with ship building, Jones suggested that such figurines depict a Papyrus Goddess. She concluded her comment by acknowledging the thorough work done by Momigliano in this presentation and by pointing out the associated insightful ideas present in the work of Andrew Shapland regarding the “Snake-Frame”.

§66. In her response, Nicoletta Momigliano emphasised that the “Snake-Frame” motif consistently appear to rest on the open palms of the figurines, whereas the item reconstructed as a snake by Evans is firmly clenched in the “votary’s” fist. She further indicates her doubts on their identification of the item held in the votary’s hand as a “snake” but mentioned that in her opinion there was no compelling reason for Arthur Evans and Halvor Bagge to fudge the reconstruction of the upper part of the item held in the votary’s hands in 1903.

§67. Jones expressed her disagreement with Momigliano, arguing that the preserved surface is rough from the hand to what looks like a break just above the curve and is smooth above it to the rounded tip, suggesting that the smooth upper part was attached.

§68. On her end, Momigliano references the meticulous description of the 1903 reconstructions of the “snake”, as they are reported in the relevant volume of the Annual of the British School at Athens and available drawings, specifically confirming the authenticity of the end piece of the motif.

§69. Andrew Shapland praised Momigliano’s presentation and suggested that some pieces of the snake, like the end, could be original but reconstructed wrongly and not “dishonestly” by Evans. Reflecting on the possibility of an alternative assembling of the pieces, he argues for their reconstruction as a snake frame. This motif, he explained, appears at around the same time as the Snake Goddesses on seal impressions at Zakros.

§70. Shapland then added that elaborately dressed women holding a snake frame is a recurrent motif on seals in Late Minoan II and III, and thus slightly later than the Snake Goddess figurine. He argued that later depictions of women with a snake frame could have “evolved” from earlier prototypes.

§71. Shapland then asked Momigliano’s opinion on what the reaction would be in Crete in case the snake motif is successfully deconstructed from the Snake Goddess.

§72. Momigliano pointed out that an attempt to present alternative reconstructions of the Snake Goddess to the Cretan public would take place in the coming July. For her, it is important that this attempt will not aim to dismiss the work of Evans, but to make the public aware of the issues linked to the current reconstruction, including among others that of symmetry and the problematic reconstruction of the snakes in the hands of the “votary”.

§73. Vassiliki Pliatsika praised Momigliano’s presentation and her project and collaborators. She observed how much potential it has in highlighting the need to showcase emblematic archaeological objects in museums, incorporating different perspectives and taking into account the huge impact that such artefacts had in 20th and 21st century CE culture.

§74. Pliatsika remarked that projects like Momigliano’s help us not only as archaeologists but also as museum specialists, to assist the public in reading and reflecting upon these iconic objects again. They also help us review our own preconceptions, improving the current display strategies and methodologies used in museums, she added. Pliatsika also praised the use of literature and art in the project to appreciate and disclose antiquities in a new light.

§75. Momigliano added that what she found most interesting was to listen to audio descriptions and reading pieces written by partially blind writers. The reason, Momigliano stressed, is because people who do not have sensory impairments such as blindness or partial blindness often do not see things in any case, or do not find the right words when it comes to describe things, while people who are blind or partially sighted can often sense other aspects and describe them and present new “views” of archaeological objects.

§76. Pliatsika suggested that next research level would be that of “dismantling” the figurines to get the answer. She then added that 3D printing may help with that, as it is becoming easier to find in museums nowadays. Pliatsika suggested making a 3D copy of a Snake Goddess, to destroy and “play” with it, and asked Momigliano if she had thought about it.

§77. Momigliano replied that it is extremely difficult to study these objects and that she could never recall the last person who actually physically handled the figurines. She added that, for example, Bernice Jones had to use photographs of them to conduct her recent analysis.

§78. Jones specified that she had been allowed to photograph the Snake Goddess upon removal of the glass case, but she was not able to handle them.

§79. Momigliano observed that it should be possible to produce 3D printing or reconstructions and even radiographies of the objects. This is much needed, she stressed, as the x-ray photographs she showed in the presentation were more than 20 years old.

§80. Jones expressed her doubts that 3D imaging can be made for the snake goddesses as they are too fragile, but it may work with good replicas.

§81. Pliatsika highlighted that the National Archaeological Museum is currently open to such research activities—namely, producing 3D images from well-photographed objects. Pliatsika added that Momigliano’s talk was also inspiring to think of removing unnecessary or false restorations from the artefacts.

§82. Momigliano replied that her project offered to pay for having 3-D images of the snake goddess figurines for some time, but unfortunately the Herakleion museum is currently reluctant to allow such work to be carried out.

§83. Roger Woodard thanked Nicoletta Momigliano for the thought-provoking talk and observed that an interesting comparison are the images of Ephesian Artemis and Zeus Labrandeus, as these deities are depicted as having a rope-like garland suspended from their wrists. One other thought, he added, goes to the cult officiants mentioned in the Linear B tablets, the key bearers, and the figure depicted as a snake goddess may actually be an officiant carrying some implements such as a snake or a rope.

§84. Momigliano replied that first and foremost what is original and what is not original needs to be assessed. She also added that, as Bernice Jones and Andrew Shapland pointed out, even if one piece is original it may have been refitted in the wrong place. It is thus important, she remarked, to evaluate what was actually there before opening up to other kinds of possible reconstructions. The snakes depicted in all the other figurines have spots, Momigliano remarked.

§85. In jest, Momigliano suggested that the reconstruction she likes best is the one done by a member of the public in Dublin, showing the votary swinging a tabby cat from its tail. She also mentioned that the “votary” as reconstructed is holding the snakes from their tails, which does not seem the safest way to handle these animals (unlike the way they are handled by the “goddess”).

§86. Jones argued that the votary varies from the other two snake goddesses, as those actually carry snakes that are endemic to Crete even nowadays, and have only one snake, with the snake’s tail in one hand and the head in the other. So, she concluded, there are many differences between these two types of figurines as the votary is also much smaller in size and wears a Near Eastern garment and hairstyle.

§87. Momigliano agreed about the differences pointed out by Jones between the “votary” and “goddess” and highlighted that herpetologists had confirmed that the Snake Goddess, unlike the “votary”, holds the snakes properly.

§88. Jones then remarked that trying to distinguish genuine parts from additions and reconstructions is a huge problem, even with x-ray analysis. She explained that in the x-ray analysis performed by Walter Müller (Müller 2003) the modern plaster was not distinguishable from the faience material of the figurines. She then concluded by hoping that in the future a new technology that will enable us to distinguish the original materials from the additions within these figurines will be designed.

§89. Rachele Pierini addressed three points. First, Pierini observed that the snakes had a prominent role in ancient sacred dances, originally performed with a living animal and subsequently substituted with a rope imitating the snake movements (Serrano Laguna 2014, with further references and details).

§90. Additionally, Pierini highlighted that first millennium BCE Greek literature attests the use of snakes within rituals. In particular, Demosthenes 18.260 refers to priests and worshippers holding the snakes next to their face and calls these snakes “fat-cheek” snakes, thus stressing a physical characteristic of these animal also connected to them being harmless reptiles (Pierini 2017 and Pierini 2020)—Pierini continued.

§91. Moreover, Pierini added that the Linear B word for rope is ru-de-a2, the initial interpretation of which was “perhaps therefore the ru-de-a2 are straps, hinges or fastenings, such as are often made of leather to attach lids to hampers, or for strengthening” (Docs2 491, 580). Such an interpretation, Pierini continued, was implemented by Melena (1976) and revisited by Peruzzi, who hypothesized the etymological connection with Latin rudens ‘rope’ (Peruzzi 1977). Currently, ru-de-a2 is interpreted as a neuter plural meaning ‘(leather) strips’ (Luján 2014; Pierini 2014), Pierini concluded.

§92. Palaima asked why the immediate suggestion for the material of which the rope was made is papyrus, having delivered a large work on “The papyrus dilemma” at the Summer 2021 MASt seminar. In the Summer 2012 Seminar Palaima showed that the images once thought to be papyrus are more likely Arundo donax found locally, along riverine areas, especially in Messenia.

§93. Jones replied that although she was unaware of Palaima’s MASt study until now, she was aware of the papyrus controversies (summarized by Porter 2000), but followed Karo’s identification of the Shaft-grave pin figurine’s headdress as papyrus in a hybrid sense because it suggested that what she held was its product of ropes (made from papyrus for Egyptian ship building, but also made of plant fibers in general) rather than Karo’s identification as garlands or chains (Karo 1930). She feels that Palaima’s point is well taken, and whether papyrus or another plant headdress, her main theory is that what the goddess holds is identifiable as its product: a rope, and, in turn, is important for possibly being the same for the Votary—Jones concluded.

§94. Palaima stressed that his point was around papyrus and the papyrus dilemma. What was being called papyrus, he explained, in a fresco fragment from Pylos was not a papyrus and, as well, other plant images were called papyrus rather loosely. He then provocatively asked whether researchers are absolutely certain that what is depicted on the snake goddesses is papyrus. In other instances, he highlighted, it turned out to be false. Palaima observed that Evans called various plant motifs papyrus but most were not such a plant, as naturalists also noted.

§95. Palaima drew the attention to the problem of Egyptomania and the willingness to find forceful connections between Minoan Crete and Egypt to prove that an Aegean branch could have matched the Egyptian society. For example, he highlighted that a connection between the wine ideogram and an Egyptian hieroglyphic sign was proposed, and Egyptian connections were sought wherever they could find them. He concluded that he does not trust this early identification for plants that could have been even imaginary, especially as papyrus did not grow in the Aegean.

§96. Momigliano then specified that Jones did not argue that all the ropes are made of papyrus.

§97. Palaima replied that he was not claiming that all ropes are made of papyrus but rather reflecting about these particular, important images that are used to reconstruct or suggest royal and palatial rituals, such as in the work of Mabel Lang and Sarah Immerwahr, and that Evans was just loosely using the term papyrus for plants that were not papyrus.

§98. Palaima added that he did not question that the rope per se could be made of papyrus, although that may also be an assumption, even though Bernice Jones has made explicit her application of papyrus to the rope because of the papyrus headdress. He thus concluded by suggesting checking what is called papyrus and why, considered that there were a number of important images connected with throne rooms that were called papyrus but have revealed not to be as such by naturalists upon careful re-examination for the Papyrus Dilemma Seminar.

§99. Artemis Karnava proposed a reflection on the stripes on clothing. The stripes, she observed, are not accidental and could have a symbolic value, even though maybe not ubiquitous. She then referred to the 500 pairs of goat horns from Akrotiri and the fact that most of them display red painted stripes. In that case, she argued, it is tantalizing to suggest that it is more than a simple decoration.

§100. Karnava also observed that Minoan figurines often have striped clothing and the female Mycenaean figurines are also wearing clothes with vertical stripes. She then concluded that even if we do not know the symbolism behind these depictions, we can observe that they are always dressed in stripes, and this must have had a specific meaning.

§101. Nicoletta Momigliano thanked Karnava for the observation and agreed to her conclusions by noting that in the Temple Repositories at Knossos there were hundreds of shells painted with red pigments and this must also have had a meaning.

§102. Karnava and Momigliano’s discussion bibliography

Bernabé, A. and E. R. Luján, ed. 2014. Donum Mycenologicum. Mycenaean Studies in Honour of Francisco Aura Jorro. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 131. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Docs2 = Ventris, M., and J. Chadwick. 1973. Documents in Mycenaean Greek. 2nd ed. Cambridge.

Jones, B. R. forthcoming. “The iconography of the Knossos Snake Goddesses based on their Gestures, Stances, Movements and Attributes.” In: Gestures–Stance–Movement: Communicating Bodies in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of a Conference at Heidelberg, 11–13 November 2021, ed. U. Günkel-Maschek, C. Murphy, F. Blakolmer, and D. Panagiotopoulos, 243–257.

Karo, G. 1930. Die Schachtgraber von Mykene. Munich.

Luján, E. 2014. “Los temas en -s en micénico.” In Bernabé and Luján 2014:51–74.

Melena, J. L. 1976. Review to Docs2. Minos 15:233–239.

Müller, W. 2003. “Minoan Works of Art—Seen with Penetrating Eyes: X-Ray Testing of Gold Pottery and Faience.” In Metron. Measuring the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 9th International Aegean Conference/9e Rencontre égéenne internationale, New Haven, Yale University (18–21 April 2002), ed. R. Laffineur and K. Polinger Foster, 147–154. Aegaeum 24. Liège and Austin.

Peruzzi, E. 1977. “A Mycenaean antecedent for rudens.” Minos 16:228–235.

Pierini, R. 2014. “Ricerche sul segno 25 del sillabario miceneo.” In Bernabé and Luján 2014:105–138.

Pierini, R. 2017. “An alphabetic parallel for Mycenaean ma-ka.” Kadmos 56:89–106.

Pierini, R. 2020. “Posibles menciones dionisíacas en las tablillas de Tebas.” In Nunc est bacchandum. Congreso en homenaje a Alberto Bernabé, ed. P. De Paz, J. Piquero, and S. Planchas, 309–316. Madrid.

Porter, R. 2000. “The Flora of the Theran Wall Paintings: Living Plants and Motifs–Sea Lily, Crocus, Iris and Ivy.” In The Wall Paintings of Thera.Proceedings of the First International Symposium. Petros M. Nomikos Conference Centre, Thera, Hellas, 30 August–4 September 1997, ed. S. Sherratt, II:603–630. Athens.

Serrano Laguna, I. 2014. “Danzas de animales micénicas.” In Bernabé and Luján 2014:163–172.

Final remarks

§103. Rachele Pierini thanked the speakers for their excellent papers and invited the audience to join the Summer 2024 MASt Seminar, to be held on Friday, June 28th and that will be devoted to Early Career Researchers (ECRs).

[1] Four snake species have been identified on Crete: besides the two mentioned above, the other two are the Balkan whip snake (Hierophis gemonensis) and the dice snake (Natrix tessellata). Of these four, only the cat snake is venomous, but its poison is not dangerous to humans.

[2] See now https://mlsg.squarespace.com/events/conversations-with-the-snake-goddess-2024 and also https://mlsg.squarespace.com/news/the-many-lives-of-a-snake-goddess-mandinada-poetry