4. The Enigma of the Eteocretans: Language, Identity, and Politics in Ancient Crete

Presenter: Jasmine Zitelli

MASt Seminar Report Summer 2024, Friday, June 28

Bronze Age Intergenerational Dialogues (BA.ID), 2:

Early Career Researchers (ECRs) at MASt,

https://doi.org/10.71160/XPWU8208

Introduction: The Discovery of the Eteocretans

§119. The debate concerning the Eteocretans officially began in 1884, when Italian archaeologist F. Halbherr discovered the first Eteocretan inscription during his investigations at the third acropolis of Praisos (Halbherr 1894:540; IC III, vii.1), an ancient polis located in eastern Crete. This discovery marked the beginning of a series of findings that would capture the attention of the academic community. The inscription garnered significant interest after its publication in 1888 by D. Comparetti (Comparetti 1888:673—676), as it documented a non-Hellenic language despite being written in the Greek alphabet. Comparetti promptly linked the language to the Eteocretan people, primarily mentioned in the Odyssey (Hom. Od. 19.172—179) as one of the pre-Hellenic groups of Crete. This connection was reported by Strabo (Strab. 10.4.6), which placed the Eteocretans in Praisos.

Figure 15. Map of central and eastern Crete, showing the main sites mentioned in the text. Drawn by author.

§120. Further excavations conducted at Praisos by the British School at Athens uncovered more Eteocretan texts (Bosanquet 1901/1902:255), confirming the presence of an ethnically diverse group that retained its local language. The plot thickened in 1936, when investigations conducted by P. Demargne and van Effenterre in the polis of Dreros, located in northeastern Crete, revealed several official texts regulating the public and religious life of the city (Demargne and van Effenterre 1937; van Effenterre 1946a:588—604.). One of these inscriptions was partially written in a non-Hellenic language resembling that used at Praisos (van Effenterre 1946b). Another text from Dreros was long thought to be bilingual (Eteocretan-Greek), however, it was later proven to be entirely written in Greek (van Effenterre 1989).

§121. A crucial moment in Eteocretan studies occurred in 1958, when S. Marinatos edited a Hellenistic inscription (Marinatos 1958) which scholars used to believe came from the territory of Arcades, in east-central Crete. The inscription was not unearthed during regular excavations but was part of the private collection of S. Giamalakis. The Arcades inscription sparked a huge debate concerning its genuineness due to the inaccurate information provided by the owner regarding its discovery circumstances and location (which is sometimes referred to as Psychro and other times as Ini in the Arcades region), as well as the unusual presence of three signs traceable to the Cretan syllabic scripts of the second millennium BCE, positioned at the end of the text. A recent analysis by C. Kritzas suggested that the inscription is a modern forgery, created on a piece of clay floor plaque of the late Roman period and then cut by forgers to shape it into a small stele (Kritzas 2005; Facchetti 2009:75—84). According to Kritzas, in addition to the chronological inhomogeneity of the letters and the similarity of the text to common Greek tombstone inscriptions, elements previously observed by other linguists (Faure 1988/1989:108), compelling evidence of forgery is demonstrated by the fact that the original surfaces of the stele show concretions and patinas that are completely missing on the later cut sides.

§122. In 2006, excavations carried out by the American School of Classical Archaeology at the Archaic site of Azoria, eastern Crete, uncovered two pithos handles, both inscribed with the same sequence: ΞΡΤΑΚ (Haggis et al. 2011:57—58; West 2015). The brevity of the inscription renders uncertain its classification as an Eteocretan text. The handles may come from the same pot and probably bear the name of the pithos owner. However, the peculiar succession of consonants and the presence of the letter 𐤐, rarely attested on the island during the Archaic period, bear resemblances to the Eteocretan inscriptions found at Praisos (PRA1.2; Duhoux 1982:164). Currently, there are six inscriptions definitively identified as Eteocretan. Five originate from Praisos, dating from the sixth to the third centuries BCE, while one hails from Dreros dating to the mid-seventh century BCE, totaling 422 characters (Duhoux 1982).

The Linguistic Studies

§123. Since the discovery of the Eteocretan inscriptions, scholars have dedicated their efforts to unraveling the mysterious language. R.C. Conway was among the first scholars to attempt to identify this language. He noted resemblances between Eteocretan and languages within the Italic linguistic family, particularly Venetic (Conway 1901/1902). Over the years, the Eteocretan language has been variously identified as Phrygian, Proto-Slavic, a Greek dialect, and even Sumerian. However, with the discovery of the Dreros texts and, notably, the publication of the Arcades inscription, two theories have gained traction: one posits Eteocretan as an Indo-European language akin to Anatolian languages, while the other places it within the Northwest Semitic language family. These perspectives stem from a broader debate regarding the nature of the Aegean substrate before the arrival of the Hellenic peoples. This controversy animated the academic community during the twentieth century and developed alongside newly acquired knowledge about ancient languages, particularly the Anatolian ones.

The Anatolian Hypothesis

§124. In 1915, Czech linguist B. Hrozný revolutionized the understanding of ancient languages in Asia Minor by deciphering the Hittite language from the Ḫattuša tablets and identifying it as belonging to the Indo-European language family (Hrozný 1915). Further research conducted between the 1920s and 1950s confirmed the linguistic link among various languages in Asia Minor, such as Luwian, Lycian, and Hittite, categorizing them as “Anatolian languages” and recognizing their Indo-European affiliation (Finkelberg 2005:42—64).

§125. The newfound insights into Anatolian languages, along with the excitement following the decipherment of Linear B in 1952, spurred increased interest in studies related to the pre-Hellenic substratum, particularly in Crete, where undeciphered scripts remained. Attention was particularly focused on Linear A, which, unlike Cretan Hieroglyphic, featured a greater number of signs and attestations. The presence of disputed suffixes like –nth– and –ss– in Greek place names led many linguists to speculate about an Anatolian-type substrate in Crete. Leonard Palmer was a prominent advocate of this theory, proposing Luwian as a possible language for Linear A (Palmer 1980).

§126. Instead, S. Davis was among the first to extend this Anatolian-type continuity to Eteocretan, suggesting it may be related to Hittite (Davis 1961). The publication of the inscription from Arcades significantly bolstered this theory. Despite doubts about its authenticity and the differences between the alphabetical sequences of the Arcades text and those of the Praisos and Dreros inscriptions, the presence of three signs in syllabic script seemed to support the hypothesis of continuity between second-millennium languages and Eteocretan. Several scholars, who advocated for an Anatolian-type substratum in Crete and proposed hypotheses about the Linear A language, also applied their interpretations to Eteocretan inscriptions, assuming they were written in the same language as the syllabic script texts. Among these scholars, M. Finkelberg suggested that this language might be Lycian (Finkelberg 2006).

§127. From an archaeological perspective, C. Renfrew’s theories on the Indo-Europeanization of the Aegean world further reinforced the notion of an Anatolian substratum in Crete. In 1987, Renfrew suggested that Indo-European languages arrived with the first farmers from Anatolia following the Neolithic revolution, around the seventh or sixth millennium BCE. This event, according to Renfrew, contributed to the spread of Indo-European languages in the Aegean world (Renfrew 1987).

The Semitic Hypothesis

§128. During the same period when the Anatolian hypothesis gained traction, an alternative theory emerged, seeking to underscore the significant influence of the Semitic world on the development of Aegean writing and culture. The proposed existence of a Proto-Indo-European or Indo-European substratum in the Aegean region challenged prevailing theories dating back to the eighteenth century, which suggested colonization of the Hellenic world by Egyptians and Phoenicians, resulting in the dissemination of their culture. In the nineteenth century, the movement for Greek independence from the Ottoman Empire fueled a strong pro-Hellenic sentiment. Particularly in Crete, the discoveries by A.J. Evans and the parallels with the culture uncovered by H. Schliemann on the mainland helped foster a strong sense of identity within the Greek world. However, this period of fervent philhellenism was also marked by widespread anti-Semitism (Bernal 1987).

§129. The Phoenicians’ role in transmitting the Greek alphabet was recognized in antiquity, as evidenced by Herodotus’s tradition (Hdt.5.58—61). While Herodotus suggests Boeotia as a possible birthplace of the alphabet, many scholars have noted the close resemblance of the Cretan alphabet to the Phoenician model. This is further supported by the persistence of the vertical stroke as a word separator in Cretan inscriptions from the Archaic period and the adoption of retrograde writing, consistent with Semitic writing conventions (Guarducci 1967:181). Additionally, the oldest evidence of Phoenician writing in Crete comes from the necropolis of Tekke near Knossos, represented by an engraved cup dating back to the ninth century BCE (Sznycer 1979).

§130. While the notion that Crete might have been the birthplace of the alphabet remains speculative, it is indisputable that the island had early exposure to the Phoenician alphabet. This is affirmed by the oldest alphabetic inscription from Crete, dated to the eighth century BCE (Duhoux 1981:288). The striking similarities between the Cretan and Phoenician alphabets, coupled with the early dating of alphabetic writing in Crete and the Semitic roots found in Linear A and B, have led to the suggestion that Phoenician influence may represent a genuine substratum.

§131. C. Gordon pioneered this theory, initially focusing on Linear A and later directing attention to Eteocretan. Gordon concluded that Eteocretan inscriptions demonstrate continuity with the Bronze Age and were written in the same language as Linear A (Gordon 1975:148—158). Once again, the edition of the false Arcades inscription played a pivotal role in bolstering this hypothesis.

§132. One of the main arguments used to support this theory is the highly conservative aspect of the Eteocretan texts, especially those from Praisos, which exhibit features closely resembling the Phoenician model. Alongside the use of the vertical bar as a word/paragraph separator, the archaic nature of the letters, and the retrograde writing pattern, a distinctive characteristic of Eteocretan inscriptions is the frequent occurrence of consonantal succession, reminiscent of the Abjad script seen in Semitic texts.

Limits of Previous Research and New Perspectives for the Eteocretan Studies

§133. The work of Gordon and Davis is now somewhat outdated, as it is based on old and inaccurate editions of the Linear A corpus as well as erroneous reconstructions of many terms found in Anatolian languages. These studies were also influenced by a true pro-Semitic and pro- Indo-European ideology regarding the pre-Hellenic substratum that characterized the academic world of those years. However, the major weakness of linguistic studies on Eteocretan, even the more recent ones, lies in the methodology applied to the texts, primarily focused on isolating lexical roots. This approach is universally adopted by linguists studying this language since it appears as the sole viable method. The scarcity of Eteocretan inscriptions, totaling only 422 characters, largely contributes to this. Additionally, these texts are often incomplete, poorly preserved, or comprised of short sequences, further hindering analysis.

§134. While the Dreros inscription presents the possibility of being bilingual (Eteocretan–Greek), it poses considerable challenges in reading and interpretation. Furthermore, the temporal gap between the two sections of the inscription raises doubts about the authenticity of the Greek translation as a faithful rendition of the Eteocretan text (van Effenterre 1946b).

§135. Compounding the scarcity of textual sources, only three out of the six Eteocretan texts display dividers. This lack of structural cues makes determining sequence breaks arbitrary, impacting the interpretative outcome. Consequently, the predominant focus on isolating lexical roots has led to interpretations suggesting linguistic connections across vastly different languages.

§136. The Arcades inscription, despite being pivotal for linguistic theories, raises several problems. Notably, the supposed syllabic signs closing the text lack exact correspondence with any known Cretan script from the second millennium BCE, and compelling evidence suggests it is a modern forgery. Furthermore, it is worth noting that the persistence of signs from the Cretan syllabic scripts of the Bronze Age into the first millennium is not unique to the Arcades inscription. This phenomenon does not necessarily indicate the survival of languages spoken in Crete during the second millennium BCE. These signs remained legible within the palace ruins but likely underwent evolution detached from their original linguistic context, transforming into religious marks or structural elements like dividers (Bousquet1938:405—408)[1].

§137. Before the Kritzas article proving the forgery of the inscription and even after, the Arcades inscription has notably influenced assumptions regarding Eteocretan, particularly the unsubstantiated belief that it directly corresponds to languages recorded in Cretan syllabic scripts of the second millennium BCE, notably Linear A.

§138. It is impossible to rule out a connection between the language of Linear A and Eteocretan since both languages remain unknown. It is noteworthy that there is a significant time gap between Eteocretan and Linear A. The latter ceased to exist within the palatial administration around the fifteenth century BCE, with its last known attestation on the island dating back around the fourteenth century BCE, recorded in clay figurine (Perna 2016:94). The oldest attested inscription in the Eteocretan language dates to around 650 BCE.

§139. Certainly, the mere temporal distance between the two languages is not sufficient to exclude continuity. In fact, the chronological gap between Linear A and Eteocretan texts might be attributed to the use or loss of a form of writing and does not necessarily affect the possibility of linguistic continuity. Furthermore, one can assume that the Eteocretan language likely existed on the island long before it was used for official and monumental inscriptions. However, it is important to consider that the syllabic scripts used on Crete in the Bronze Age mainly represent the languages of the ruling elites responsible for political and often religious affairs in palatial society. This monopolization of writing provides an incomplete picture of the linguistic diversity on the island during the second millennium BCE.

§140. Regarding cultural continuity and identity, the coexistence of two different populations, the Minoans and the Myceneans, during the late Bronze Age is also an important factor to consider.

§141. Tsipopoulou coined the term “Mycenoans” to describe the ethnicity of Cretans between the end of the Bronze Age and the beginning of the Iron Age (Tsipopoulou 2005:303). This identity appears to have been formed as early as the twelfth century BCE and blends Minoan and Mycenaean elements. According to Tsipopoulou, the Eteocretans constructed their identity by reconnecting with a mixed, non-purely Minoan past to differentiate themselves from the Dorians, a new group on the island seen as a possible threat.

§142. This research aims to approach the Eteocretan issue from a new perspective, integrating insights from the archaeological context of inscriptions and the significance of bilingualism in the first millennium BCE Crete. In doing so, it is essential to delve into the origins and implications of the term “Eteocretan” by reexamining ancient sources referring to this population.

The Archaeological Evidence

§143. As a part of the Eteocretan studies, the archaeological context of the inscriptions holds a prominent significance. As previously indicated, the Eteocretan texts primarily originate from Praisos and Dreros.

§144. Praisos is a polis that emerged during the Geometric period (eighth century BCE). The ancient city sprawls across three hills or acropolises. The Eteocretan inscriptions were unearthed along the slopes and atop the third acropolis, dubbed Altar Hill, since it hosted a prominent sanctuary, originally comprising solely an altar. The sanctuary area yielded a rich votive deposit dating from the eighth to the fiftieth centuries BCE (Halbherr 1901). This deposit included terracotta figurines, votive bronzes (comprising mainly miniature and life-size weaponry and armor), vases, and animal bones. By the fifth century BCE, the sanctuary underwent significant development, marked by the building of a temenos enclosing the altar. Also dating to this age, are numerous architectural terracotta, likely associated with structures erected within the sacred area, possibly including a temple, although no conclusive evidence has emerged (Bosanquet 1901/1902). The excavation also yielded Greek-language inscriptions along with the Eteocretan ones. The Greek text consists of decrees and treaties of Hellenistic data. Both Eteocretan and Greek inscriptions likely leaned against the temenos walls (Duhoux 1982:57).

§145. The deity venerated on the third acropolis of Praisos remains uncertain. The abundance of weaponry suggests Athena (Duhoux 1982:56—57), while Bosanquet identified the sanctuary with that of Zeus Dicteus, located by Strabo in Praisos (Bosanquet 1908/1909:351; Bosanquet 1939/1940:64—66). However, it is important to consider that bronze offerings were widespread in Archaic Crete and did not necessarily indicate the deity’s identity. The weaponry attests to aristocratic involvement in the cult, particularly the agonistic and martial aspects of elites charged to administrate the sanctuary, and reflects the protective role expected from the deity (Morgan 1990:19; Prent 2005:369; De Polignac 1995:26, 49). The elite nature of this sanctuary is further underscored by remnants indicative of communal dining, suggesting its civic function in which established citizens participated (Prent 2005:497—498; Erickson 2009:386—389).

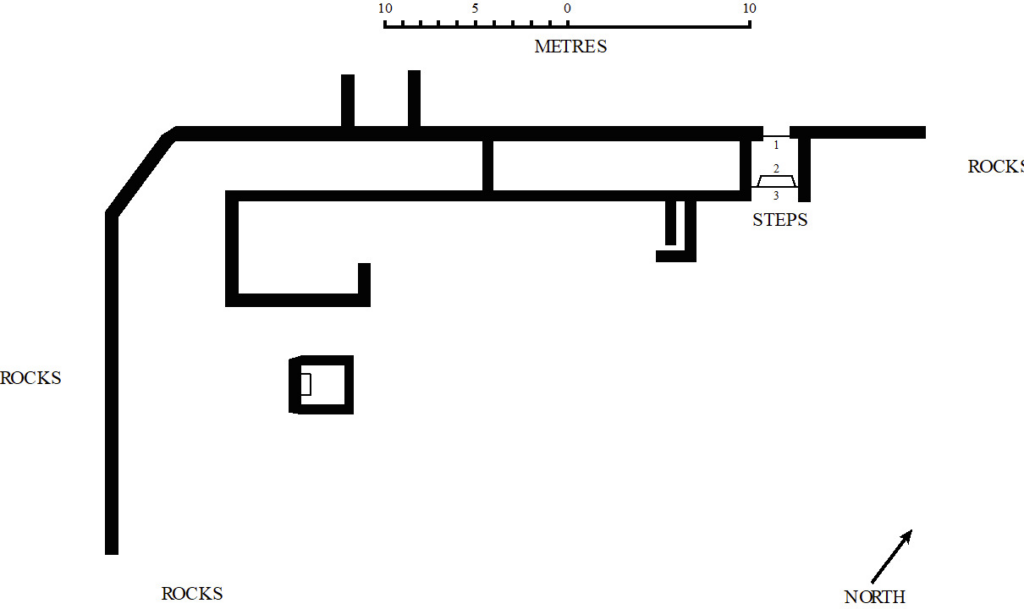

Figure 16. Plan of the temenos. Drawn by author after Bosanquet 1901/1902, figure 27.

Figure 16. Plan of the temenos. Drawn by author after Bosanquet 1901/1902, figure 27.

§146. Similarly, Dreros, also a geometric polis, spanned two acropolises. The Eteocretan inscription lay in a Hellenistic cistern situated in the saddle between the two acropolises. Numerous other archaic inscriptions, written in Greek, were recovered from the cistern, primarily laws and decrees regulating the city’s public and religious life (Demargne and van Effenterre 1937; van Effenterre 1946a). The inscribed blocks were likely part of the eastern wall of the adjacent temple of Apollo Delphinios. Dating back to the eighth century BCE, this temple contained an eschara, a bench, and a keraton altar in its main room (Marinatos 1936). The temple follows the Hearth Temples typology known in Crete, used for smaller-scale meals of magistrates (Prent 2005:441—476, 462). Its civic significance is evident not only from the presence of official inscriptions but also from its proximity to the agora, situated immediately to the north. Although the agora dates to the Hellenistic period, it is supposed that the Archaic agora occupied the same or a nearby location (Zographaki-Farnoux 2014).

Figure 17. Dreros. The Agora area. Photo by author.

§147. While the specific content of the Eteocretan texts remains unknown, it is possible to deduce their nature from accompanying Greek texts. These Greek inscriptions typically consist of official texts, laws, and decrees. The placement of the Eteocretan texts within sacred spaces, which concurrently served civic functions, further underscores their essentially public nature. These sanctuaries served as platforms for elites to assert their role and influence through lavish votive offerings, solidifying civic cohesion through communal banquets and ceremonies. Consequently, sanctuaries emerged as early forms of civic space, and in the cases of Praisos and Dreros, they served as venues for expressing an emerging ethnic identity.

§148. However, the phenomenon of bilingualism appears to differ between the two city-states. Dreros exhibits a less pronounced presence of bilingualism, yet the use of the local language for drafting official inscriptions seems comparatively limited. Only one surviving inscription in the local language has been found in Dreros, coexisting with Greek texts. Furthermore, evidence suggests that the use of the local language ceased in the first half of the seventh century BCE.

§149. In contrast, Praisos showcases a different linguistic dynamic. Eteocretan inscriptions emerged in the sixth century BCE and persisted until the Hellenistic period. Despite the widespread use of Greek in Praisos, indicated by Classic coins (Svoronos 1890:285—292), Eteocretan remains the sole language deliberately chosen for official inscriptions, at least until the third century BCE when Greek inscriptions began to appear alongside Eteocretan ones. The state of preservation of both Greek and contemporary Eteocretan texts makes it impossible to determine whether one was a translation of the other. However, it is interesting to note that in Praisos, the Greek texts appeared alongside the spread of treaties and agreements between different poleis in Crete, particularly the isopoliteia treaties, which granted full reciprocal citizenship rights to the citizens of the contracting cities. One of the purposes of these treaties was to strengthen the bond between allies. Observance of a treaty between two city- states was part of the duties of citizenship; for this reason, young ephebes swore to respect the treaties their polis had established with the other contracting community (Chaniotis 1996:124). Members of the contracting polis were often present during the proclamation of this oath. Contracts and treaties were also read out by the magistrates on special festive occasions, always in the presence of members of the contracting city (Chaniotis 1996). In Praisos, the Greek texts from the third acropolis are mostly fragments of treaties with other poleis, especially Lyttos. As for the Eteocretan texts from Praisos, the only word that can be distinctly read is φραισο- (PRA 2.2; PRA .6; Duhoux 1982:69), the name of the city. No other toponyms can be read in the Eteocretan texts. Therefore, it can be assumed that inscriptions in the local language regulated the internal life of the city. At the same time, Greek spread for drafting official texts when treaties with other poleis began to be established and read in public during specific ceremonies in the presence of the contracting partners. However, this hypothesis remains speculative, given the small number of Eteocretan texts and their incomplete state.

§150. The need for alliances may have stimulated the phenomenon of bilingualism in Praisos, while the prevalence of a Dorian elite or more in general Dorian influence in Dreros may have prompted the abandonment of the local language, at least in the official sphere. In this regard, it must be emphasized that the city of Praisos seems to have preserved more conservative cultural aspects than Dreros. For example, the sanctuary on the third acropolis remained en plein air at least until the Classical period.

§151. Additionally, local deities, such as the famous Zeus Dicteus, seem to have predominated in Praisos, while Dreros appears to have been Hellenized much earlier, perhaps influenced by its alliance with Knossos.

The Origins of the Eteocretans

§152. The Eteocretans are deemed to have inhabited Crete during the Bronze Age, before the arrival of the Hellenic people. From an archaeological point of view, Dreros and Praisos arose at the beginning of the Iron Age. However, traces of settlements dating to the final phase of the Bronze Age have been unearthed in the small hill immediately east of Praisos, known as Kypia Kalamafki (Whitley et al. 1999:238—242), and in the small hill of Kephali Limnes (Gaignerot-Driessen 2016:223), east of the Dreros Hills, where the Eteocretans may have originally settled.

§153. The ancient sources attest to the antiquity of the Eteocretans, revealing them as an ethnic group known as far back as Homer’s time. In the Odyssey, they are listed among the diverse ethnolinguistic communities of Crete (Hom. Od. 19.172—179). Ephorus (FGrHist 70 F145), Pseudo-Scymnus (Pseudo-Scymn. 541—548), and Diodorus Siculus (Diod. Sic. 5.64.1) subsequently portray them as one of the oldest indigenous peoples of the island, ruled by King Kres. However, Strabo is the first and only author to locate the Eteocretans in Praisos (Strab. 10.4.6).

§154. Since the ancient sources mentioning the Eteocretans emphasize their antiquity, they have always been used to support the link between this population and the Minoans. However, doubts arose as early as the early twentieth century regarding the authenticity of the Homeric passage mentioning the peoples of Crete (Beloch 1910:219—221). Mentions of the Eteocretans disappear from historical records until the fourth century BCE (Ephorus). This hiatus is puzzling, particularly given Herodotus’s account in the Histories (Hdt. 7.169—171), where Praisos, alongside Polichna, abstained from participating in the Cretans’ punitive expedition to Sicily following the death of King Minos. While the inhabitants of Praisos lay claim to their antiquity and autochthony in Herodotus’s account, they are never called Eteocretans. This suggests that the term “Eteocretan” may have first appeared in the fourth century BCE, potentially coinciding with the interpolation of Homeric passages.

§155. The term Eteokretes has a Greek etymology (Chantraine 2009:381), prompting speculation about whether it was the Hellenic peoples who coined the term to indicate the indigenous inhabitants of Crete, or if the Eteocretans themselves chose a Greek name to identify themselves. The unmistakably Greek origin of the name is confirmed by similar formations, notably Eteobutadai and Eteokarphatioi, both of which have connections to Athens. The former refers to an Attic ghenos (Marginesu 2001:48—49), while the latter denotes certain inhabitants of the island of Karpathos, situated east of Crete, mentioned in Athenian records from the Classical period and in a Hellenistic decree concerning Athens and the community of the Eteokarpathioi (Foucart 1888).

§156. Y. Duhoux hypothesizes that the term “Eteocretan” could be the Greek translation of an originally indigenous name meaning “true Cretans.” This term might have developed after the Mycenaean conquest of the island (1450 BCE) or after the Dorian invasion (1150 BCE). According to Duhoux, the success of this term in Homeric poems might have led to the creation of similar names, such as Eteokarpathioi (Duhoux 1982:17—21). However, the possible interpolation of the Homeric passage in the late Classical or Hellenistic period, the absence of any mention of the Eteocretans in Herodotus, and the significant influence exerted by Athens in the Aegean world between the Archaic and Classical periods make it plausible that the term “Eteocretan” was coined after, or at least at the same time as, the spread of the term Eteokarphatoi. In both cases, the resonance of Athenian terms, such as Eteobutadai, might have inspired its creation.

§157. There are further parallels between the Eteocretans and Athens. From the fourth century BCE onwards, sources describe the Eteocretans as indigenous people descended from Kres. This inevitably evokes the myth of autochthony elaborated by Athens during the fifth century BCE. The Athenians, who previously traced their lineage back to Hellen through the character of Ion, departed from this tradition to align themselves with the mythical figure of Erechtheus. This shift allowed them to establish a stark contrast with other Hellenes, ultimately evolving into a profound dualism between Greeks and non-Greeks (Hall 1989). In the case of Crete, the Eteocretans rally around the name of Kres. They are not just the authentic Cretans but, more importantly, the genuine descendants of Kres. Praisos asserts its autochthony and distinctiveness from other Cretans in Herodotus’s account by refusing to claim Minos, the legendary king of the island. Praisos, as indicated by Strabo, was the stronghold of the Eteocretans, thus likely affiliated with Kres rather than Minos. The Eteocretans are not the only ones to follow the model of Athens; numerous other poleis, between the Classical and Hellenistic periods, reworked or invented myths centered on local eponymous heroes, often mentioned in Homeric poems, claiming their autochthony. Examples are the inhabitants of Amathus, on the island of Cyprus, who are recorded in fifth- and fourth-century sources as autochthonous, having as their mythical ancestor Kinyras, the only Cypriot mentioned in the Homeric poems, who was present in Cyprus before the Achaean arrival (Petit 1995). Amathus, too, preserves a local language which alongside Greek is employed in the writing of official texts (Steele 2013:160—172).

The Rise of the Eteocretan Identity

§158. There is certainly a significant difference between the Athenian experience and the myth of autochthony developed by poleis such as Praisos. While the Attic dialect was part of a broader context of Greek linguistic traditions, the situation in Praisos illustrates the persistence of a local idiom on an island that had become entirely Dorian. However, in this regard, it is crucial to consider the role language plays in the formation of ethnic identity.

§159. The term Eteocretan marks the formation of an ethnic identity. Studies on ethnicity in the ancient world show that ethnic groups are social entities rather than biological ones. Attributes like language, religion, and material culture contribute to this identity, with a common ancestor serving as a fundamental criterion. This group must accept and recognize the descent, even if its historical accuracy is uncertain (Hall 1997; Hall 2002).

§160. According to this perspective, it is plausible that not only the poleis displaying a local language were Eteocretan, but also any communities tracing their lineage back to the shared ancestor, Kres. For example, in Phaistos, a genealogy attributed to Cinaethon of Sparta links Rhadamanthys to Kres (Federico 2008). Even though no Eteocretan inscriptions come from there, this suggests the possibility that Phaistos, too, may have distanced itself from the traditional association with Minos, aligning itself with Kres and adopting an “Eteocretan” identity. However, caution is warranted, as genealogy alone, like language, is not a sufficient criterion for defining an exclusive or oppositional ethnic identity (Malkin 1998:61).

§161. Even in the case of Dreros, an Eteocretan-type ethnic identity is only presumed. The example of Athens demonstrates that a common language does not preclude the formation of a distinct identity. Similarly, the potential shared language of Praisos and Dreros does not necessarily indicate that these two poleis shared the same Eteocretan ethnic identity. While literary sources link Praisos to the Eteocretans, there is no mention of Dreros as an Eteocretan polis. Furthermore, there is no association with Kres, around whom the specific Eteocretan identity is consolidated. Therefore, it is important to distinguish between the phenomenon of bilingualism and the emergence and institutionalization of an ethnic identity known as Eteocretan. Bilingualism has been documented in Crete since Archaic times and clearly indicates the survival of local peoples expressing their distinct identity from the Dorian one. However, the term Eteocretan refers to a specific ethnic identity centered around Kres. The creation of a collective name is precisely one of those elements that enable an ethnic group to be recognized in the historical record. It should also be noted that in the same Homeric passage, the Eteocretans are mentioned along with other local peoples of Crete, outlining the complex ethnic and linguistic scenario of the island.

§162. The rise of an ethnic identity involves reclaiming a distant past and cultural heritage. Communities project their history into a mythical past to create a sense of temporal continuity, often to legitimize present circumstances or to deliberately forge a narrative where none existed (Whitley 1995:49). Elites play a significant role in this process, fostering unity and cohesion within the community. Asserting indigenous roots and authenticity, like the Athenian paradigm, holds political significance. Political alliances and perceived threats are prominent in molding or strengthening ethnic identities (Hall 1989:12).

§163. In the case of Crete, the threat to autonomy came from influential cities like Knossos or Gortyn seeking to dominate the island. The myth of the Eteocretans may have originated from attempts to maintain autonomy, especially evident in Praisos, the sole Eteocretan city mentioned in historical records. Praisos adopted this myth of autochthony during its period of expansion, which led to conflicts with Hierapytna, its rival in eastern Crete (Spyridakis 1970). Conversely, Dreros came under the influence of Knossos early on, potentially leading to the abandonment of its local language and, possibly, its local ethnic identity.

Conclusion

§164. In investigating the Eteocretan phenomenon, it becomes essential to analyze the historical and archaeological backdrop where bilingualism manifests. While there is no explicit prohibition against linking the Eteocretan language with that of Linear A, current data does not firmly establish this connection, even though it remains the most logical way to follow at present. Cretan bilingualism, varying from one city-state to another, suggests that writing in Crete was a political act (see Detienne 1988:40—41; Brixhe 1991:55), with the local language surviving in official texts displayed within civic and religious spaces managed by elites. Despite their limited understanding, Eteocretan texts offer insights into the rise of civic and ethnic identity, used by elites to legitimize themselves and foster community cohesion, thereby safeguarding polis autonomy. Language is only one of the factors that contributed to the creation of the Eteocretan identity. Praisos appropriated or even created this identity and made it the bulwark of its myth of autochthony inspired by the Athenian model.

§165. Bibliography

FGrHist: Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker. F. Jacoby 1923—1958.

IC: Guarducci, M. Inscriptiones creticae opera et consilio Friderici Halbherr collectae/ curavit Margherita Guarducci, Roma.1935—1950.

Beloch, K.J. 1910. “Origini cretesi.” Ausonia 4:220—221.

Bernal, M. 1987. The Afroasiatic Roots of Classical Civilization 2. New Brunswick and New Jersey.

Bosanquet, R.C. 1901/1902. “Excavations at Praesos, I.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 8:231—270.

Bosanquet, R.C. 1908/1909. “The Hymn of the Kouretes.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 15:339—356.

Bosanquet, R.C. 1939/1940. “Dicte and the temples of Dictaean Zeus.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 40:60—77.

Bousquet, J. 1938. “Le temple d’Aphrodite et d’Arès à Sta Lenikà.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 62:386—408.

Brixhe, C. 1991. “La langue comme reflet de l’histoire, ou les éléments non doriens du dialecte crétois”. In Sur la Crète antique: histoire, écritures, langues, ed. C. Brixhe, 43—77. Nancy.

Chaniotis, A. 1996. Die Verträge zwischen kretischen Poleis in der hellenistischen Zeit. Stuttgart.

Chantraine. P. 2009. Dictionnaire étimologique de la langue grecque. Histoire des mots. Paris.

Comparetti, D. 1888. “Iscrizioni di varie città cretesi.” Museo Italico di Antichità Classica 2:669-—686.

Conway, R.S. 1901/1902. “The pre-Hellenic inscriptions of Praesos.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 8:125—126.

Davis, S. 1961. The Phaistos Disk and the Eteocretan Inscriptions from Psychro and Praisos. Johannesburg.

De Polignac, F. 1995. Cults, Territory and the Origins of the Greek City-State. Chicago and London.

Demargne, P., and H. van Effenterre. 1937. “Recherches à Dréros.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 61:5—32.

Detienne, M. 1988. “L’espace de la publicité : ses opérateurs intellectuels dans la cite”. In Les savoirs de l’écriture en Grèce Ancienne, ed. M. Detienne, 29—81. Lille

Duhoux, Y. 1981. “Les Etéocrétois et l’origine de l’alphabet grec.” L’Antiquité Classique 50:287—294.

Duhoux, Y. 1982. L’étéocrétois: les textes, la langue. Amsterdam.

Erickson, B. 2009. “Roussa Ekklesia, Part 1: Religion and Politics in East Crete.” American Journal of Archaeology 113/3:353—404.

Facchetti, G. 2009. Scrittura e falsità. Rome.

Faure, P. 1988/1989. “Les sept inscriptions dites ‘Étéocrétoises’ reconsiderées”. Kretika Cronika 28/29:107—108.

Federico, E. 2008. “Una genealogia festia in Cinetone spartano. Dati per una cronologia.” Creta Antica 9:287—300.

Finkelberg, M. 2005. Greeks and Pre-Greeks. Aegean Prehistory and Greek Heroic Tradition. Cambridge.

Finkelberg, M. 2006. “The Eteocretan Inscription from Psychro and the Goddess of Thalamai.” Minos 37/38: 95—97.

Foucart, P.F. 1888. “Décrets athéniens du IVe siècle.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 12:53—179.

Gaignerot-Driessen, F. 2016. De l’occupation postpalatiale à la cité-État grecque: le cas du Mirambello, (Crète). Leuven and Liège.

Gordon, C. 1975. “The Decipherment of Minoan and Eteocretan.” Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland 2:148—158.

Guarducci, M. 1967. Epigrafia Greca, I. Caratteri e storia della disciplina, La scrittura greca dalle origini all’età imperiale. Rome.

Haggis, D.C., M.S. Mook, R.D. Fitzsimons, C.M. Scarry, L.M. Snyder, and W.C. West. 2011. “Excavations in the Archaic Civic Buildings at Azoria in 2005-2006.” Hesperia 80:1—70.

Halbherr, F. 1894. “American Expedition to Crete under Professor Halbherr.” American Journal of Archaeology 9/4:538—544.

Halbherr, F. 1901. “Cretan Expedition XVI: Report on the Researches at Praesos.” American Journal of Archaeology 5:371—392.

Hall, E. 1989. Inventing the Barbarian. Greek Self-Definition through Tragedy. Oxford.

Hall, J. 1997. Ethnic Identity in Greek Antiquity. Cambridge.

Hall, J. 2002. Hellenicity. Between Ethnicity and Culture. Chicago.

Hrozný, B. 1915. “Die Lösung des hethitischen Problems.” Mitteilungen der Deutschen Orient- Gesellschaft 56:17—50.

Kritzas, C.B. 2005. “The “Bilingual” Inscription from Psychro (Crete). A coup de grâce.” ΜΕΓΑΛΑΙ ΝΗΣΟΙ. Studi dedicati a Giovanni Rizza per il suo ottantesimo compleanno 1:255—261. Catania.

Malkin, I. 1998. The Returns of Odysseus: Colonization and Ethnicity. Berkeley.

Marginesu, G. 2001. “Gli Eteobutadi e l’Eretteo: la monumentalizzazione di un’idea.” Annuario della Scuola archeologica di Atene e delle missioni italiane in Oriente 79:37—54.

Marinatos, S. 1936. “Le temple géometrique de Dréros.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 60:214—285.

Marinatos, S. 1958. “Γραμμάτων διδασκάλια.” In Minoica: Festschrift zum 80, Geburstag von Johannes Sundwall, ed. E. Grumach, 226—227. Berlin.

Morgan, C. 1990. Athletes and Oracles. The Transformation of Olympia and Delphi in the Eighth Century B.C. Cambridge.

Palmer, L. 1980. The Greek Language. London.

Perna, M. 2016. “La scrittura lineare A”. In Manuale di epigrafia micenea, ed. M. Del Freo and M. Perna, 87—116. Padova.

Petit, T. 1995. “Amathous (Autochtones eisin). De l’identité amathousienne à l’époque des royaumes (VIIIe -IVe siècles).” Sources, Travaux historiques 43/44:51—64.

Prent, M. 2005. Cretan Sanctuaries and Cults. Continuity and Change from late Minoan III C to the Archaic Period. Leiden.

Renfrew, C. 1987. Archaeology and Language. The Puzzle of Indo- European Origins. London.

Smith, A. 1986. The Ethnic Origins of Nations. Oxford.

Spyridakis, S. 1970. Ptolemaic Itanos and Hellenistic Crete. California.

Steele, P. M. 2013. Eteocypriot in context: Eteocypriot at Amathus. Cambridge.

Svoronos, I.N. 1890. Numismatique de la Crète ancienne. Paris

Sznycer, M. 1979. “L’inscription phénicienne de Tekke, près de Cnossos.” Kadmos 18:89—93.

Tsipopoulou, M. 2005. “‘Mycenoans’ at the Isthmus of Ierapetra.” In Ariadne’s threads: connections between Crete and the Greek Mainland in Late Minoan III, ed. D’Agata A. L. and J.A. Moody, 303—352. Athens.

Van Effenterre, H. 1946a. “Inscriptions archaïques crétoises.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 70: 588—606.

Van Effenterre, H. 1946b. “Une bilingue étéocrétoise?.” Revue de Philologie 20:131—138.

Van Effenterre, H. 1989. “De l’étéocrétois à la selle d’agneau”. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 113:447—449.

West, W.C. 2015. “Informal and Practical Uses of Writing on Potsherds from Azoria, Crete.” Zeitschrift für Papyrologie und Epigraphik 193:154—155.

Whitley, J. 1995. “Tomb cult and Hero cult. The uses of the past in Archaic Greece.” In Time, Tradition and Society in Greek Archaeology, ed. N. Spencer, 43—63. London.

Whitley, J., M. Prent and S. Thorne. 1999. “Praisos IV: A Preliminary Report on the 1993 and 1994 Survey Seasons.” The Annual of the British School at Athens 94:215—264.

Zographaki, V., and A. Farnoux. 2014. “Mission franco-hellénique de Dréros.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 138:785—791.

Footnote

[1] One of the Eteocretan inscriptions from Praisos (PRA 5) also bears a sign similar to the Linear A syllabogram used as a divider (IC III.vi.4).

For a discussion of this and the other ECRs’ papers, go the MASt Summer 2024 report landing page and scroll to §166