1. The Enigmatic Exchange: Cross-Material Influence Between Crete and the Mainland in Late Bronze Age Glyptic

Presenter: Diana Wolf

MASt Seminar Report Summer 2024, Friday, June 28

Bronze Age Intergenerational Dialogues (BA.ID), 2:

Early Career Researchers (ECRs) at MASt,

https://doi.org/10.71160/QSMN2851

Introduction

§13. Used as sphragistic instruments,[1] tools for securing and identification, as jewelry, amulets, and status symbols,[2] seals were an indispensable part of life in Aegean Bronze Age Crete.[3] Their multiple functions made these small, engraved objects carriers of meaning that contributed to the formation, maintenance, and transformation of social relations. While Pre- and Protopalatial seals have already been covered extensively by comprehensive studies,[4] Late Minoan (LM) seals have not yet received such detailed treatment, the exception being the hard-stone seals of the “Talismanic” style and metal signet rings.[5] Although many detailed iconographic studies exist,[6] their objective is not to provide a comprehensive treatment with in-depth discussions of materials, techniques, chronology, and other craft-related aspects of the seals. Soft-stone seals are especially under-studied, despite the large number of currently over 1.500 known LM soft-stone seals. In comparison, hard stone seals from this period number about 1.300, and ca. 200 metal seals have been documented.

§14. Soft-stone seals have the longest, most prolific history of Bronze Age Cretan seals, dating from Early Minoan (EM) II—LM III.[7] Engraved with simpler techniques and easily abraded, seals cut in soft materials (Mohs 1–3/4) are less impressive in appearance than their hard stone (Mohs 4+) and metal counterparts. Hard-stone seals began to be produced during the Protopalatial period, following the introduction of the lapidary lathe, which enabled the cutting of semi-precious stones.[8] In scholarly discussions, this resulted in comparative approaches to soft-stone and hard-stone seals that often highlight the aesthetic and technological superiority of the latter. Evan’s notion of “primitive pictographic figures” on soft-stone seals that “from the second Middle Minoan period onward were transformed into intaglio types of the highest naturalistic and artistic merit”[9] is reflected throughout the literature of the 20th century and can still be recognized in more recent contributions. Boardman in his seminal work Greek Gems & Finger Rings did not bother to explore the “many poorer stones […] mainly of interest for their subjects since they exhibit no technical bravura and several are simply hand cut in softer stones.”[10] This apprehension is still reflected in later archaeological reports that tend to specify soft-stone seal finds only when individual pieces are considered exceptional due to an iconography of special interest or excellent preservation.[11] Otherwise, they are usually mentioned in side notes on “μικρά ευρήματα”[12] (small finds) without specification. As a result, the corpus of soft-stone seals has been relatively neglected, rarely receiving individual attention without being utilized as a simplistic backdrop to other groups.[13] The soft stones’ aesthetically less striking appearance, their proclivity to poorer states of preservation, and the graphic impression of intaglios created by hand-held tools (often described as ‘simple’ or ‘crude’) have led scholars to internalize the role of this object group as subordinate to other seal types and to suggest that soft-stone seals were owned and used by low-ranking social groups.[14]

§15. Comparisons of cross-material influence can be made most effectively through seals with similar motifs, as this allows for observing and comparing the execution of specific details. This approach is particularly suitable for evidence from the Late Bronze Age (LBA), a period rich in seals featuring detailed representational imagery across various materials. The lack of comprehensive studies of the iconography, style, and distribution of soft-stone seals has resulted in simplified models explaining their relationship to other glyptic groups. Regarding hard-stone seals specifically, previous scholarship has proposed two models of cross-material influence: Either the production of soft-stone seals was thought largely dependent on the production of hard-stone seals, or vice versa. For example, Krzyszkowska stated that “[…] in composition, pose, and the rendering of anatomical parts, soft stone engravers clearly emulated their cousins working in other materials.”[15] Betts, on the other hand, contended that “[i]nfluence more often passed in the other direction, hard-stone engravers attempting to mimic techniques or follow motifs used more consistently by their colleagues working in soft stone.”[16] Systematic iconographic analysis, however, strongly suggests that these models both fall short of the reality of LBA glyptic development. Here, we explore cross-material influences in LBA glyptic based on an extensive study of over 1.000 LM soft-stone seals with representational iconography. Methodologically, it involved detailed scrutiny of all available impressions of LM soft-stone seals at the CMS Archive Heidelberg (over 960) and close examination of approximately 80 original seals.[17] Based on the results of this extensive study, the following discussion begins with stylistic transfer, going on to motif exclusivity and transfer, thereby revealing connections between soft-stone and hard-stone seals as well as between Crete and the mainland. A concluding case study of a signet ring from Pylos illustrates various aspects of motif transfer in the context of Minoan-mainland connections during this period.

Stylistic Transfer

§16. Due to the different production techniques of each material group (Table 1), stylistic analysis is usually not useful for comparing seals made of different materials.[18] Style is primarily dependent on technology, specifically the way tools are used,[19] and the material of the workpieces (e.g. soft, medium, hard stone, their respective density, granularity, etc.).[20] Clear stylistic influences between seals of different materials are evident only in a few instances.

Table 1. Production techniques for different materials prevalent in LBA Aegean glyptic. In bold: materials used for LBA representational soft-stone seals.

§17. Due to the limited length of this article, style groups are referred to without detailed specification. The transfer of stylistic traits can best be observed in a small number of soft-stone and hard-stone seals, of which three examples are given here.

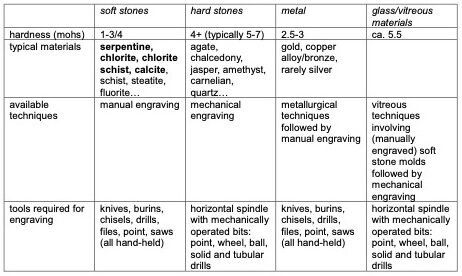

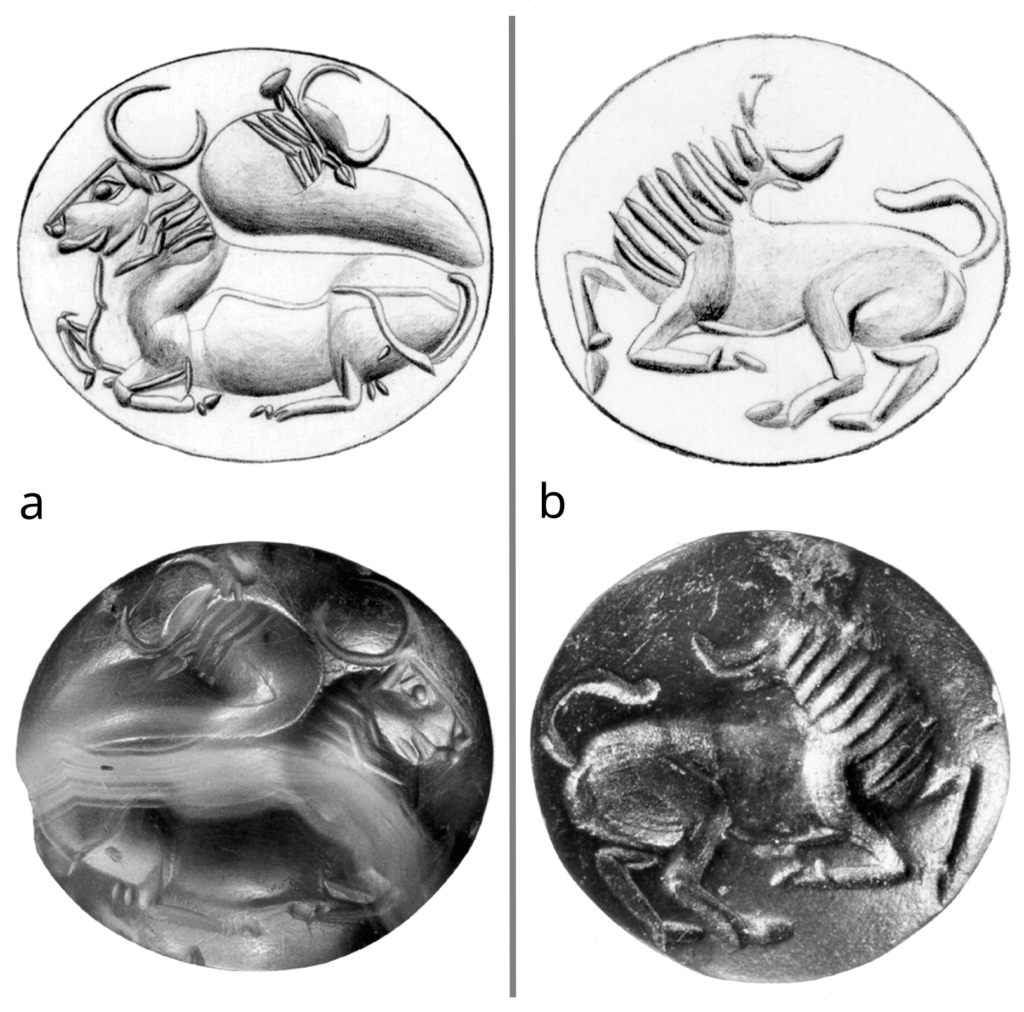

Figure 1. Transfer of stylistic traits between soft-stone and hard-stone seals: Cut Style in a LM I soft- (a, CMS III no. 444) and a *LB I-II hard-stone (b, CMS VS1B no. 37), “spectacle eyes” in LM IIIA soft- (c, Heraklion Museum Seal inv. no. 2540) and *LB IIIA1–2 hard-stone (d, CMS V no. 188), LM IIIA/B soft-stone engraved in hard-stone style (e, CMS IS no. 147) with a *LB IIIA1 hard-stone example (f, CMS I no. 105). Drawings and modern impressions. *CMS dating. Not to scale (a–b, d-f courtesy CMS Heidelberg; c courtesy M. Anastasiadou).

§18. The first example of stylistic transfer from hard to soft stone is a serpentine seal depicting a goat, reportedly from Knossos (Figure 1a). The undisguised tool marks on the piece consist of simple straight lines along the back and horns and drilled solid dots for the eye, muzzle, and hooves of the wild goat. Combined with limited internal modeling, these are characteristic features of the Cut Style.[21] Wild goats are a favorite motif of this style that appeared mainly in LM IA and to a lesser extent in LM IB (Figure 1b). It relies on mechanical engraving, allowing for precise, straight lines. A second example is the rendering of “spectacle eyes.”[22] This typical Final Palatial (FP) trait observed in many hard-stone seals features on a LM IIIA/B serpentine seal from the cemetery of Kalochorafitis (Figure 1c).[23] This idiosyncratic feature is created by a solid drill and a tubular drill which together produce a large dot-eye with a circular outline (Figure 1d). A third case of stylistic transfer is found on a soft-stone seal of unknown provenance (Figure 1e). It not only copies hard-stone style traits but was also engraved with rotary tools.[24] The seal depicts a ram with a stout, well-modeled body and thin, short legs, features typical of hard-stone seals (Figure 1f, further CMS X no. 122).

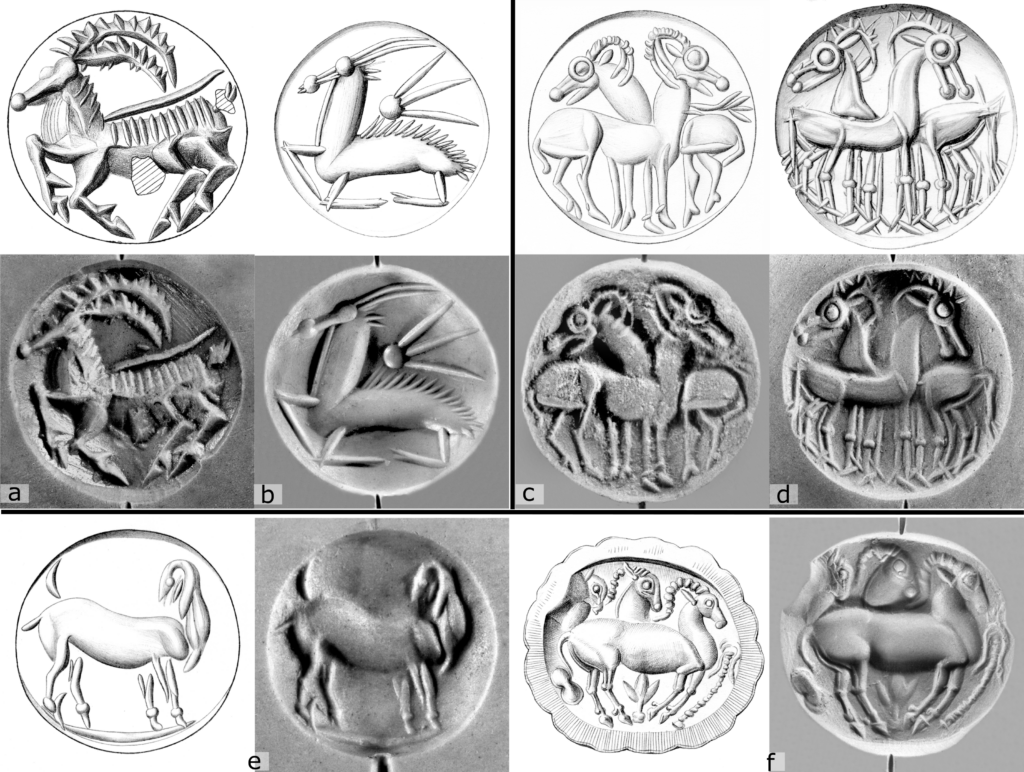

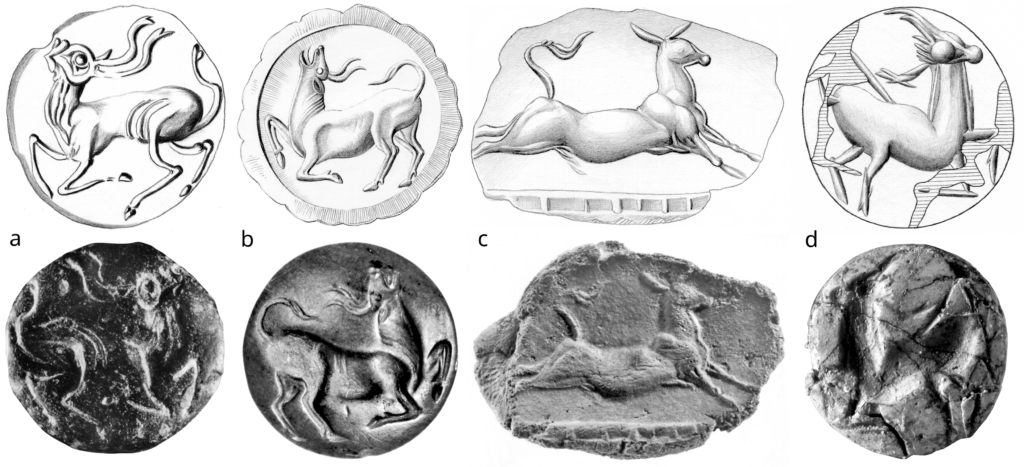

Figure 2. Stylistic transfer from soft-stone to hard-stone seals: soft-stone style deer on a *LB I–II amethyst lentoid (a, CMS II3 no. 74) and typical soft-stone deer on a LM I serpentine seal (b, CMS II4 no. 113); (c, CMS II3 no. 210) *LB IIIA carnelian seal showing a deer attacked by a lion. Modern drawings and impressions. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§19. Examples of stylistic transfer from soft-stone to hard-stone are rare. Two amethyst lentoids, one from Knossos (Figure 2a) and one from Mycenae,[25] depict deer with bodies covered in short dashes or dapples, a feature typical of Neopalatial soft-stone seals (Figure 2b).[26] Additionally, the collapsing pose of the Knossian specimen[27] is characteristic of soft-stone seals of the period, whereas hard-stone seals usually depict deer in attack scenes (Figure 2c).

Motif Exclusivity and Motif Transfer

§20. Soft-stone seals are best compared to other glyptic materials based on their imagery. By eliminating the more restrictive category of style and focusing on iconography, larger clusters of seals can be assembled and compared. In the following, we will discuss motif exclusivity and transfer from the perspective of soft-stone seal imagery. Motif exclusivity where certain motifs are restricted to one material type is rare. Seal designs usually range from being mostly soft-stone-related to mostly soft-stone-unrelated. Typical soft-stone motifs were sometimes replicated in hard materials, and vice versa. The next section provides a basic overview of the material specificity of common motifs in LM glyptic.

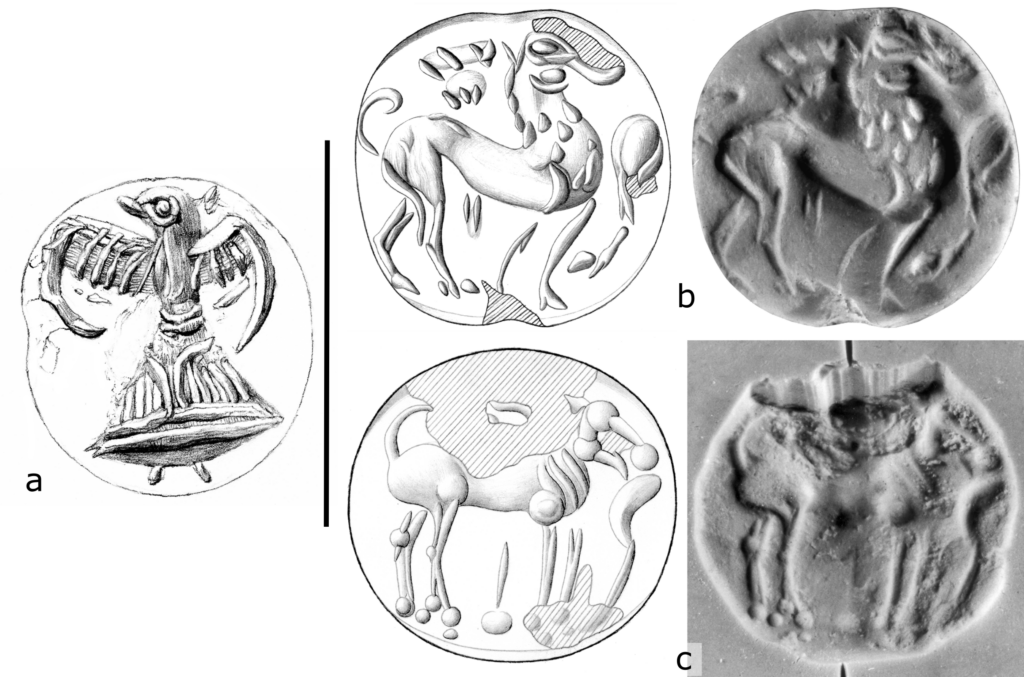

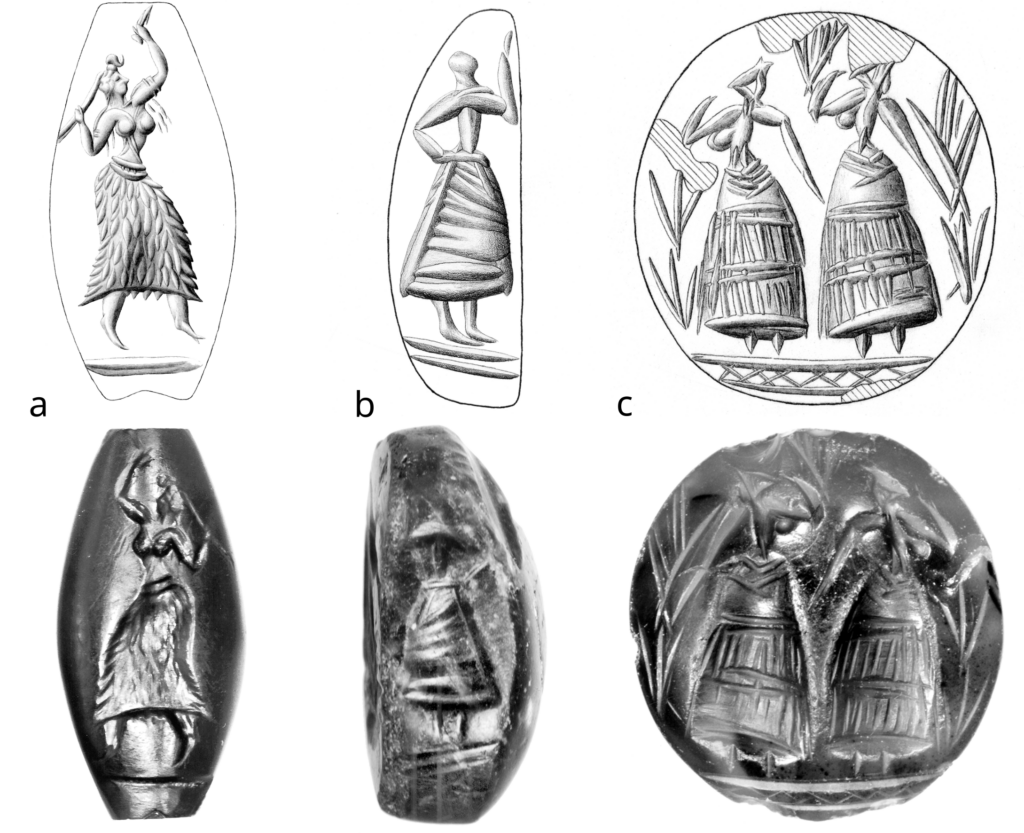

Figure 3. Example of a Neopalatial hybrid bird-woman (a, CMS VII no. 143), and of a Final Palatial LLC seal (b, CMS II4 no. 74) with the only non-soft-stone example (c, CMS VS1A no. 107). Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§21. Based on the available evidence, only one iconographic group appears exclusively in soft stone.[28] The Neopalatial hybrid bird-women (Figure 3a) and variants of these fantastic creatures have not been recognized in any other Aegean object with pictorial imagery. Similarly, the FP lion-leg-column (LLC) group is found almost (?) exclusively in soft stone (Figure 3b). A single possible exception is a seal of indeterminate material that has been described as a very soft, possibly vitreous or paste-like, white substance (Figure 3c).[29] Its eroded surface reveals traces of rotary tools despite the soft material—possibly favoring an interpretation of the material as vitreous or perhaps glazed.[30]

Predominantly soft-stone motifs

§22. Three Neopalatial soft-stone groups revolve around female human figures performing a selection of gestures (Figure 4).[31] Over 50 seals bear motifs related to one of three types: the female figure may appear alone on the seal face (Figure 4a), in pairs of two (Figure 4b), or alone and carrying a quadruped (Figure 4c).[32] The seal provenances, when known, cluster around north-central and central Crete.

Figure 4. Gesturing Female Figures on Neopalatial (LM I) soft-stone seals. Type 1: Individual figure (a, CMS III no. 352). Type 2: pairs of figures, here with pointed headdress (b, CMS XII no. 168). Type 3: Individual figure carrying a quadruped (here a caprid) over her shoulder (c, CMS II4 no. 111). Drawings and seal faces. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§23. This imagery is not exclusive to soft stone, as evidenced by several hard-stone seals with the same or closely related motifs, as well as occurrences on metal signet rings. Intriguingly, evidence comes predominantly, and in the case of hard stones exclusively, from the mainland, where seals are typically found in LH II contexts. Judging by the context dating, it appears that the inception of the soft stone seals, some of which are found in LM IA contexts, predates the hard-stone specimens, but further observations are necessary to corroborate this.[33] The following instances of Minoan soft-stone motifs can be evidenced on mainland hard-stone seals:

§24. Type 1: Individual female figures performing gestures

Material: carnelian | shape: amygdaloid | provenance: Vaphio (Figure 5a)

Material: amethyst | shape: scaraboid | provenance: Aidonia (Figure 5b)

§25. Type 2: Pairs of female figures performing gestures

Material: carnelian | shape: lentoid | provenance: Modi (Figure 5c)

Material: carnelian | shape: lentoid | provenance: unknown[34]

Material: gold | shape: signet ring | provenance: Pylos (Figure 13a)

§26. Type 3: Female figure carrying a quadruped

Material: carnelian | shape: lentoid | provenance: Vaphio (Figure 6a)

Material: agate | shape: lentoid | provenance: Vaphio (CMS I no. 222)

Material: hematite | shape: lentoid | provenance: Epidauros (Figure 6b)

§27. Variations of Types 1–3

Imagery: 3 female figures| material: lead | shape: signet ring | provenance: Malia (CMS VS1A no. 58)

Imagery: 3 female figures | material: chlorite mold for metal seal production | provenance: Malia[35]

Imagery: 2 females, one carrying a quadruped | material: chalcedony | shape: lentoid | provenance: Vaphio (Figure 6c)

Figure 5. Neopalatial soft-stone seal imagery on *LB I–II semi-precious sealstones found on the mainland, Type 1 (a, CMS I no. 226, and b, CMS VS3 245b) and 2 (c, CMS VS3 no. 80). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

Figure 6. Neopalatial soft-stone seal imagery on semi-precious sealstones found on the mainland, gesturing females Type 3 (a, CMS I no. 220 [*LB II], and b, CMS I no. 221 [*LB I–II]) and variation of Type 2 and 3 (c, CMS VS1A no. 369 [*LB I]). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§28. These seals feature the same constellations and gestures found on the soft stones. However, details are often modified or added, such as ground lines (Figures 5, 6b–c). In particular, the hard-stone images tend to occupy more space, while the larger surface of the metal seals was used to render more figures. Their style varies from including organic forms to degrees of linearity and abstraction. Idiosyncratic Minoan styles related to hard-stone seals are also present, as testified by the Cut Style seal in Figure 6c. The hard-stone lentoids tend to be larger (median ∅ 2,1 cm) and thicker (median Th. 0,88 cm) than the soft-stone examples (median ∅ 1,7; Th. 0,6 cm),[36] and the range of seal shapes is wider. The fact that all hard-stone seals come from mainland contexts (where known) suggests that these examples in particular, were designed exclusively for mainland consumption. Interestingly, the Cretan soft-stone seals derive predominantly from upper-tier settlement contexts, some associated with religious activities, at Knossos, Archanes, Malia, Agia Triada, Gournia, Tylissos, and Petras, for example.[37] The mainland seals, on the other hand, were recovered from burial contexts.

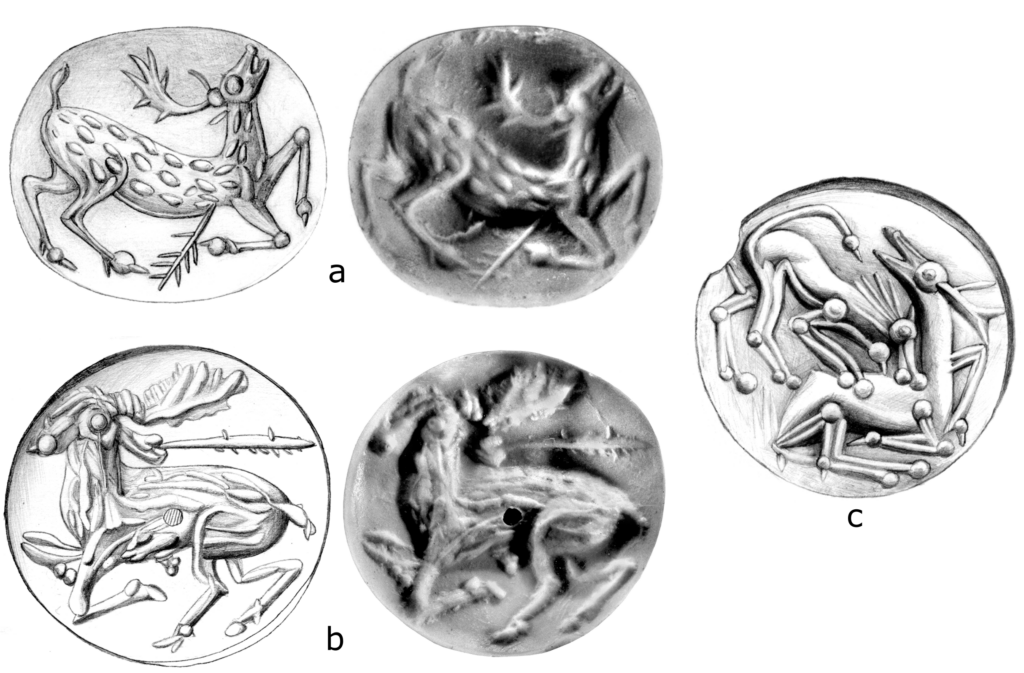

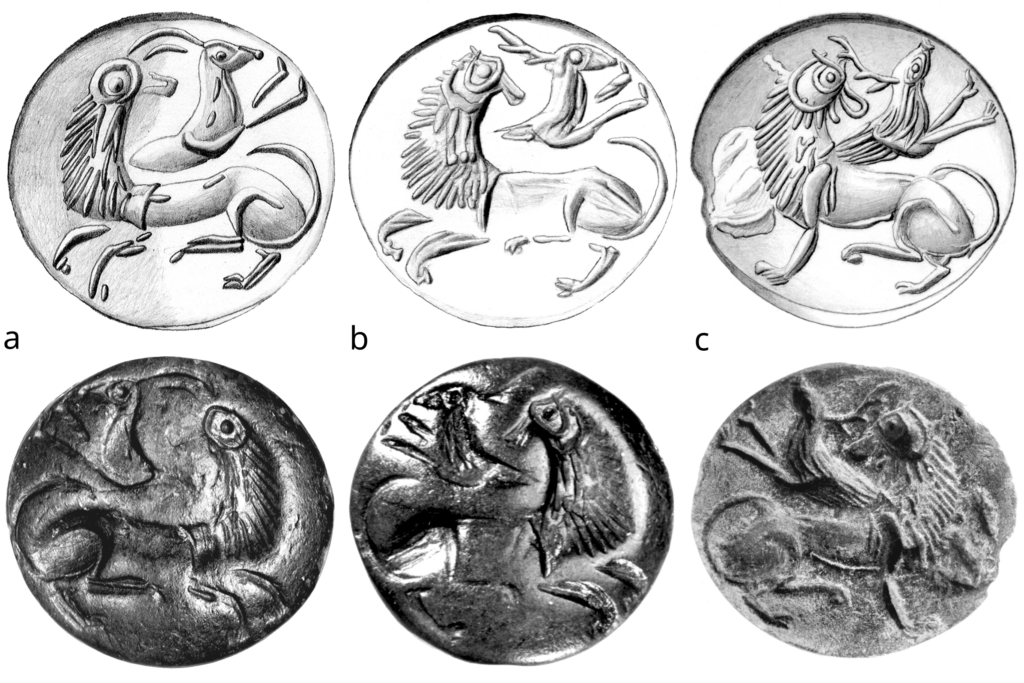

Figure 7. Soft-stone seal examples of the LM I Leaping Lion’s Prey group. Drawings and seal faces, CMS XI nos. 50, 22; CMS V no. 222. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§29. Another idiosyncratic LM soft-stone seal group is that of the Leaping Lion’s Prey (LLP, Figure 7).[38] LLP seals depict a seated or recumbent lion, regardant, facing an animal of prey leaping through the background. It is one of the most widespread groups among the corpus of LM soft-stone seals and found throughout north-central Crete, with some imports to the Argolid and Korinthia. The soft-stones date to LM IA/B-early. The hard-stone seals on the mainland are found in later contexts, (Kallithea-Patras: LH IIIA–C; Kalapodi: LH IIB–IIIA1; Mega Monastiri: LH IIIA–B), again suggesting that these succeeded the inception of the soft-stones.

§30.

Material: carnelian | shape: amygdaloid | provenance: Achillion, Larisa (Figure 8b)

Material: carnelian | shape: lentoid | provenance: Mega Monastiri, Larisa (Figure 8c)

Material: carnelian | shape: lentoid | provenance: Kalapodi (Figure 8d)

Figure 8. Neopalatial soft-stone seal imagery on semi-precious sealstones found on the mainland, Leaping Lion’s Prey group: CMS VS1B no. 176 (*undated); CMS V nos. 750, 725 (*LB I–II), CMS VS3 no. 63 (*LB II–IIIA1). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§31. These examples adhere closely to the original imagery, although the lentoids include an additional ground line (Figure 8c–d). Several seals are in the Cut Style (Figure 8a–c), an idiosyncratic Neopalatial hard-stone style often exported from Crete.[39] Nevertheless, their imagery is clearly derived from the soft-stone repertoire (Figure 7) and finds no parallels in other materials. Compared to their soft-stone equivalents, the LLP hard-stone seals are significantly larger. The soft-stone group’s median diameter is 1,76 cm, whereas that of the lentoids in the hard-stone group is 2,4 cm. In comparison to the Neopalatial soft-stone lentoids, the latter’s median thickness is even twice as large (1,2 vs. 0,6 cm; Figure 14). It appears that one soft-stone lentoid from Epidauros (Figure 7c) connects these two phenomena. Apart from its unusual size (2,55 × 2,35; Th.0,9 cm), it is engraved in a typical Minoan material and style.[40] Is it possible that this is an instance of a soft-stone seal intended for trade with the mainland? Its provenance at Epidauros corresponds to that of a hematite lentoid (Figure 6c) showing a female figure bearing a quadruped, which, as suggested above, was presumably also made for mainland consumption. On Crete, LLP seals are found in a variety of contexts, such as the palatial buildings at Archanes or Zominthos, the agora at Malia, or the peak sanctuary of Mt. Giouktas, but also in burials at Archanes-Katsoprinias and Poros-Katsambas.[41] The mainland hard-stone seals are, yet again, found exclusively in necropoleis.

§32. Both groups suggest that Minoan soft-stone seal images were transformed into hard-stone seals specifically for mainlanders. Based on context dating, it appears that the Cretan soft-stone seals preceded the mainland hard-stone seals. However, stylistic factors, like the prevalence of the LM IA–B Cut Style, suggest caution, as the motif’s presence in different materials may in fact be more contemporary than indicated by context dating. Modifications were made to accommodate different aesthetic preferences, including material, shape, size, and scaling of the motifs. Current evidence does not conclusively determine whether the hard-stone seals were engraved in Crete or on the mainland. It was previously proposed that Cretan artisans may have traveled to the mainland during the Neopalatial period to satisfy the demand of local elites for Minoan artifacts, since there was no tradition of seal engraving in early Mycenaean Greece.[42]

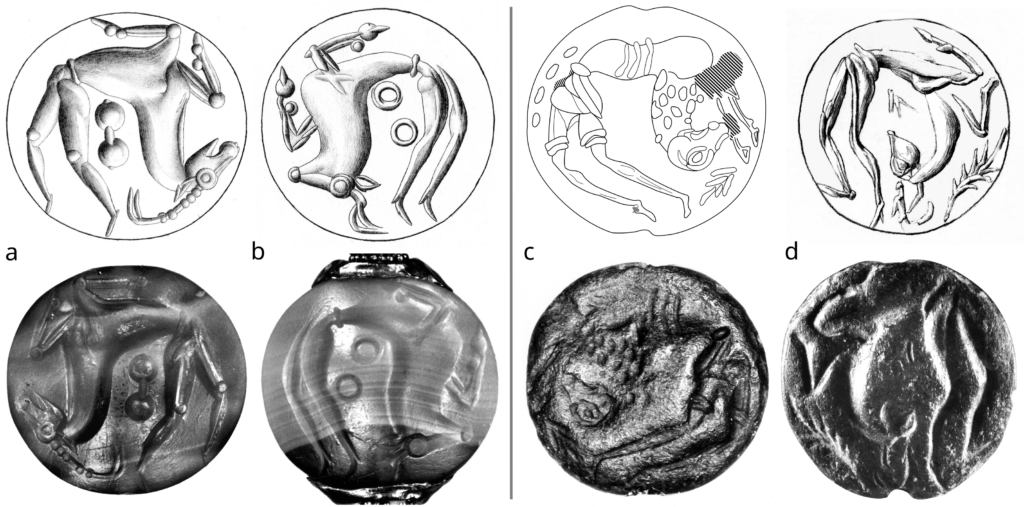

Motifs not primarily associated with soft-stone seals

§33. Two examples of motifs not typically associated with soft-stone seals that are rendered in soft stone are given here. The first comprises bi-somatic hybrids (Figure 9), fantastic creatures with the lower body of a human and the foreparts of a quadruped. This novel motif in FP hard-stone seals is attested in over thirty instances (e.g. Figure 9a–b). However, the motif occurs only twice in soft stone (Figure 9c–d). These are a lion- and a goat- or deer-man, both following the same compositional principles: a twisted mid-section, elongated legs, large heads, oriented along the circular seal face.

Figure 9. Bi-somatic hybrids on *LB II–IIIA1 hard-stone seals, example of a goat-man (a, CMS VS3 no. 11) and bull-man (b, CMS VS3 no. 150); and the only two soft-stone seals of the group, a lion-man (c, Heraklion Museum Seal inv. no. 2309) and goat- or deer-man (d, CMS VI no. 300). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (c by author, rest courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§34. The second example is a soft-soft stone seal influenced by a long-recognized hard-stone seal group discussed by Pini and Drakaki.[43] The original hard-stone image, discussed as Bildthema der zwei gelagerten Rinder (motif of two recumbent bovines), consists of two bovines, one lying behind the other (Figure 10a). The animal in the foreground is in profile, gardant, the one in the background has its head turned away from the viewer, in frontal view. Typically, their necks are striated as if wrinkled. This feature and the position of the head are reproduced on a soft-stone seal reportedly found at Kalyves (Figure 10b). The producer of the seal must have been familiar with the traditions of hard-stone seal engraving and may have been skilled in both free-hand and mechanical engraving techniques, with the necessary knowledge of how to adapt from one medium to the other. The adaptation is evident in the differences between the soft-stone seal, which lacks the depiction of the recumbent bovine in the foreground, and its extended neck folds, resulting from hand-engraving a soft material, which lacks the precision achievable in mechanically engraved hard-stone intaglios.

Figure 10. Typical hard-stone seal motifs (a, CMS IS no. 20) and a rare example in soft-stone (b, CMS IS 100). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

Motifs not restricted to a specific material

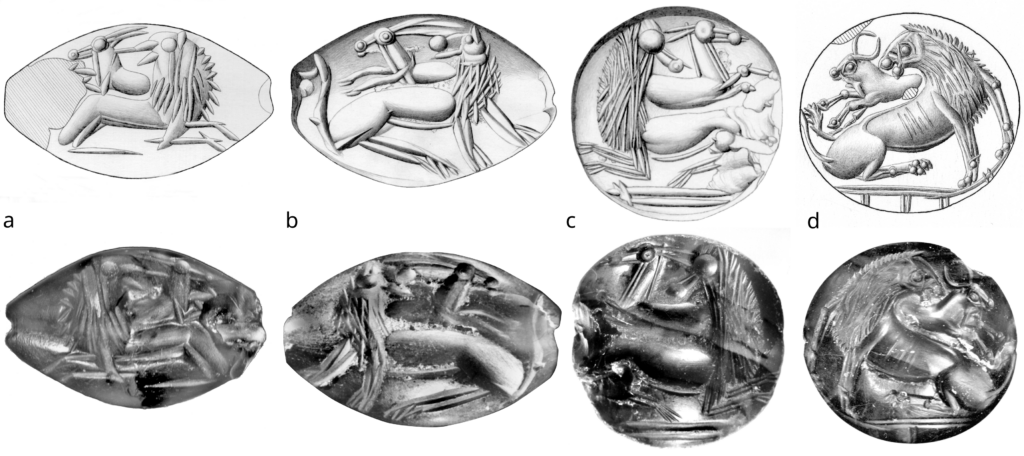

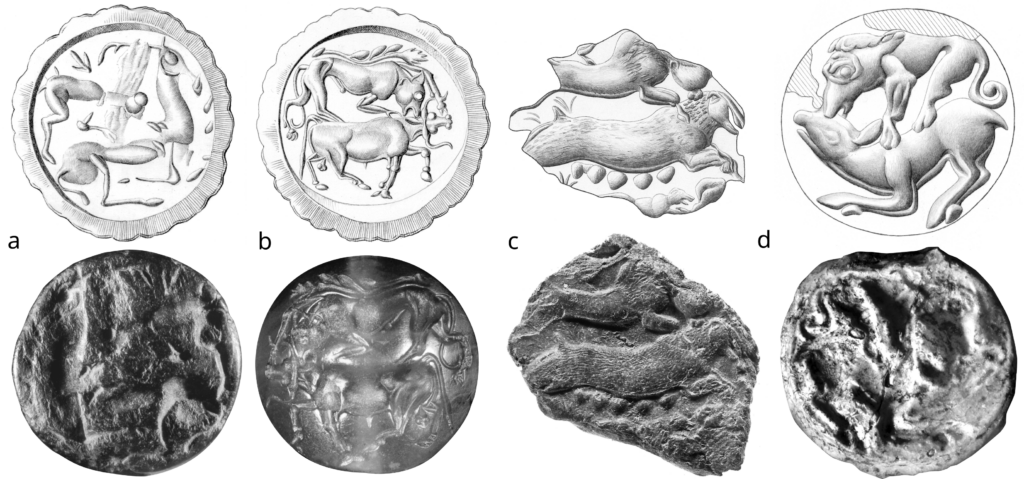

§35. Many images of LM soft-stone seals are also present in vitreous materials, metal, and hard stone. Among these are representations of a single quadruped, be it standing or sitting, gardant or regardant. For the most part, the observation made by Krzyszkowska that engravers of soft- and hard-stone seals, as well as manufacturers of metal signet rings, were using the same patterns remains valid.[44] A full description is beyond the purview of this work, so only two examples of this common phenomenon are given. Running or collapsing bovines (Figure 11) reflect the occurrence in the Neopalatial record, while animal-attack scenes (Figure 12) represent the FP period.

Figure 11. Neopalatial examples of iconographic types that are found throughout different materials: running / leaping bovines on a LM I soft-stone (a, CMS VIII no. 126), a *LB I–II hard-stone (b, CMS I no. 234), a *LM I metal seal impression (c, CMS VS1A no. 145), and a *LB II(?) engraved glass seal (d, CMS I no. 148). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

Figure 12. Final Palatial examples of iconographic types that are found throughout different materials: animal-attack imagery on a LM II–IIIA soft-stone (a, CMS I no. 511), a *LB II–IIIA1 hard-stone (b, CMS I no. 70), a LB II–III metal-seal impression (c, CMS II8 no. 342, dating cf. Becker 2018, A 171), and a *LH IIIA1–B engraved glass seal (d, CMS I no. 100). Drawings and seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§36. The execution of shared motifs in different materials results in several differences. The degree of internal detail is reduced on soft-stone and glass seals, richer on hard-stone, and most elaborate on metal seals. Individual motifs may be combined into more elaborate representations on hard-stone and metal seals. For example, running / collapsing bovines are regularly combined with a human leaper in metal, i.e. they are merged to form bull-leaping scenes (Figure 11c), whereas animal-attack scenes may include additional attackers below the prey, or details such as landscape elements (e.g. CMS II6 no. 274 and II8 no. 192).

Summary of findings

§37. The discussion of motif exclusivity and transfer exposes the recurrence of distinctly soft-stone seal-related motif groups on semi-precious seals found in mainland contexts. On Crete, the home of the motifs, these images never appear in hard-stone seals. Mainlanders, unlike Minoans, generally did not use and own soft-stone seals in this period, as suggested by their sporadic appearance in LH II contexts.[45] However, the archaeological record suggests that mainlanders valued semi-precious sealstones engraved with Minoan motifs, prizing large seals in vibrant colors.

§38. The analysis of hard-stone seals found on the mainland with Cretan soft-stone seal imagery leads to the following findings:

- The hard-stone seals are often stylistically different from one another. This suggests that more than one individual was involved in their production.

- The mainland seals include details not found in the Minoan soft-stone seals, like ground lines.

- The hard-stone lentoids from the mainland are considerably larger and thicker than the Minoan soft-stone seals bearing the source motif.

- While the motifs in soft stone occur almost exclusively in lentoid seals, the shapes of the hard-stone specimens are more diverse, even though the motif was originally designed for a round seal face, which led to difficulties in transferring it to another ‘frame’ such as the amygdaloid shape.

- While the Neopalatial soft-stone seals from Crete are predominantly, albeit not exclusively, found outside of funerary contexts, the mainland hard-stone seals with secure provenances always derive from funerary contexts, implicating a rather different social role and context of the seals there.

Soft Materials—Strong Connections: the Pylos Gold Signet Ring 2 and Minoan Soft-Stone Seals

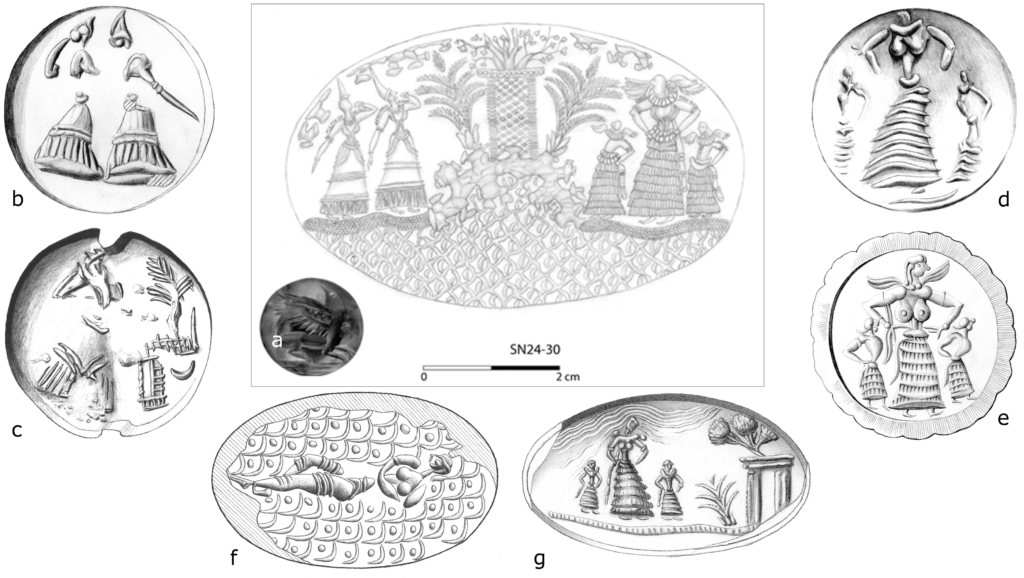

§39. This article has discussed two main phenomena: cross-material links between different seal types and the transfer of distinct soft-stone seal motifs to semi-precious seals for mainland consumption. Cross-material influences and the export of Minoan imagery for mainland consumption culminate in a gold signet ring discovered in the LH II “Grave of the Griffin Warrior” at Pylos.[46] Ring 2 provides a unique case study for discussing these cultural phenomena (Figure 13a). The craftsperson(s) responsible for the signet ring’s imagery combined individual motifs known from different types of sealstones, thereby creating an extended scene.

Figure 13. Pylos Ring 2 (SN24-30) and motif parallels in LM I soft stone (b–d, CMS XI no. 282, CMS IX no. 163, CMS II3 no. 218), *LB II hard stone (e, CMS I no. 159), and *LM I metal signet ring impressions (f–g, CMS II8 no. 264, CMS II6 no. 1). Drawings of seal faces. *CMS dating. Not to scale (a Courtesy of The Palace of Nestor Excavations, The Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati, drawing T. Ross; rest courtesy CMS Heidelberg).

§40. Ring 2 has been published in detail,[47] so the following description is limited to the most relevant aspects. The intaglio depicts five female figures to the left and right of a built structure. To the right (from the impression) is a group of three female figures wearing horizontally banded skirts and a fleeing cloth around the neck. The central figure is taller and gestures with her hands to her hips. Her body is frontal, with her head and feet facing the structure. The smaller figures on either side are also facing the center of the intaglio, but in profile, likely mimicking her gesture, though only one arm is visible. To the left, two differently dressed female figures with pointed head ornaments, depicted in profile, are making an asymmetrical gesture with an outstretched rear arm and a raised and bent front arm. The built structure is positioned on an elevated outcrop and flanked by two palm trees. A foliage tree appears to be growing from within or behind it. The figures stand on a hatched ground line beneath which a reticulated pattern appears to represent the sea.

§41. This imagery combines motifs individually known from the Minoan, particularly the soft-stone, glyptic repertoire. The pair of women with the pointed headdress is attested on a minimum of six soft-stone seals (i.a. Figures 13b, 4b). Examples come from Gournia (CMS II3 no. 236), and reportedly Knossos (Figure 13b, CMS VI no. 288), others have no known provenance (Figure 4b). The five extant hard-stone examples of pairs of gesturing female figures lack the headgear and are, moreover, considered here as derivatives of the soft-stone group (cf. above with Figure 5c). The three heraldically arranged female figures on the opposite side find a close parallel on a soft-stone lentoid (Figure 13d). The main differences are related to technology (amounting to style), material, and scaling. More intricate details can be seen on the signet ring, such as the gowns’ vertical folds, intricate waistbands, collars, and necklaces. The motif is further found on an agate lentoid from Mycenae (Figure 13e). This piece should also be considered in the context of Minoan seals that were exported for consumption on the mainland. Indications for this lie in the considerably larger diameter and thickness (∅ 2,1; Th. 0,8 cm) of this lentoid compared to the corpus of Neopalatial soft-stone lentoids (∅ 1,7; Th. 0,6 cm). Another constellation of this type is attested in the impression of a metal signet ring from Agia Triada (Figure 13g). The data on this constellation is, therefore, inconclusive as to its possible origins within glyptic in either metal or soft stone. The Agia Triada impression includes a depiction of a built structure with a foliate tree: Although this is different from that on the Pylos ring, the same spatial context is evoked. Such shrines can also be found on soft-stone seals with female figures: One prominent example renders a female figure gesturing towards the structure (Figure 13c). Finally, the reticulated pattern of the sea is testified by three other metal signet rings. One is the so-called ‘Ring of Minos’ where the interpretation is made clear by the presence of a boat on the sea-pattern.[48] The other two instances are preserved by their impressions, one on a string nodule from Knossos (Figure 13f), the other on the infamous ‘Master Impression’ from Chania.[49]

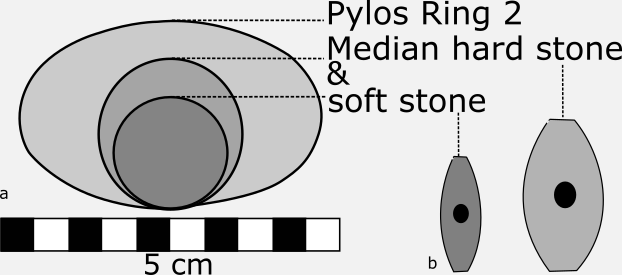

§42. The large size of Ring 2 (Figure 14a) allows it to combine and expand motifs that otherwise tend to occur in isolation. The soft-stone repertoire in particular, contains many recurring motifs, most notably the duo of female figures with the pointed headdresses. Others, such as the trio, are found on metal, soft-, and hard-stone seals—although the latter are suggested to be mainland-targeted derivatives of Minoan soft-stone images. The structure with a tree occurs in both soft-stone and metal seals. Surprisingly, the iconographic repertoire of hard-stone seals seems to have been less significant as a source material. Whether this is a case of data bias resulting from preservation is unclear, although it appears probable given the evidence for motif transfer from Cretan soft-stone to mainland hard-stone seals as discussed in the previous sections.

Figure 14. Comparison of the dimensions of Pylos Ring 2 and the median diameters of the hard-stone and the soft-stone lentoids in this study (a); comparison of the median thickness of the soft- and hard-stone lentoids in this study (b) (line art by author).

Conclusions

§43. The findings suggest that, contrary to previous views, cross-craft influence between soft-stone, hard-stone, and metal seal manufacturers was not unidirectional. Instead, the boundaries between different materials and seal types were open to reciprocal influence. The semi-precious sealstones found on the mainland but engraved with Minoan soft-stone motifs in Minoan hard-stone styles, like the Cut Style, demonstrate the seal cutters’ knowledge of different seal types (in terms of material and style), their ability to switch between these media and respective technologies, as well as a “consumer-oriented” approach on behalf of the commissioners.

§44. Appearances of the discussed Minoan soft-stone seal motifs, as well as of the individual elements combined in the imagery of the Pylos Ring 2 in hard stone are found exclusively on the mainland and in funerary contexts. Semi-precious stones were greatly favored there, whereas soft-stone seals were of little relevance in the Early Mycenaean period. These hard-stone seals, it is argued here, were a product derived from Minoan soft-stone prototypes (regarding imagery) but adapted in hard stone (sometimes copying Minoan hard-stone styles) to meet mainland tastes and needs. While the Cretan soft-stone seals relate to representational structures in upper-tier settlement areas, spaces of ritual practice, and only rarely feature in burials, it appears that mainlanders appreciated their larger-scale hard-stone versions for their representative quality within a social arena connected to signification through burial customs.

§45. Accepting this hypothesis prompts a consideration of Pylos Ring 2 as a product intended for mainland consumption—rather than a reflection of Minoan cultural traits or a means of contextualizing previously ‘fragmented’ images belonging to a hypothetical “complete” scene from a nowadays lost instance in the Minoan iconographic repertoire. While it may be appealing to use the signet ring to elucidate the social contexts and roles of motifs found on Minoan soft-stone seals, this approach risks conflating the emic understanding with an outsider’s interpretation. Variations in mainland seal usage impede drawing conclusions about Minoan soft-stone motifs and their societal function, given the distinctiveness of mainland society (or societies). While individual motifs may have been associated with particular social practices or beliefs in Crete—predominantly among living members of the community—, in a mainland context, this same imagery may have served a conceivably different function, related—as far as the extant evidence goes—exclusively to burial practices. The adaptation and combination of motifs in semi-precious stones and gold may have functioned as a branding device and cultural marker of foreign origin, exoticism, or possibly “mystical” associations which enhanced their perceived value and ultimately, their owners’ prestige. This may explain the larger size of the mainland seals and the predilection for precious materials.

§46. In conclusion, it is conceivable that mainlanders used seals very differently, likely as prestige objects, during the Early Mycenaean period. Qualities like the exoticism of the motifs and foreign origin of the materials were probably paramount—and likely to obscure—any concern with the original “meaning” of these objects in their vernacular context. Simultaneously, this enigmatic exchange between objects previously considered crude and restricted to the Minoan lower social strata,[50] on the one hand, and mainland prestige objects, on the other, highlights the interconnections among seal-craft technologies and the versatility of their mutual influence, while simultaneously challenging our previous assessment of the social role of the soft-stone seals on Crete. Finally, it should be noted that this is only a case study, offering preliminary insights into the cross-material influence between Crete and the mainland during the LBA. A comprehensive analysis of imagery and techniques is necessary to substantiate the observations presented here and to better define the local origins of certain motifs in different areas of Crete.

Acknowledgements

§47. I am deeply grateful to the MASt seminar team for the opportunity to contribute to this Early Career Researcher installment and to the three anonymous reviewers for their highly constructive feedback.

§48. This research was made possible through the support of the Fonds de la Recherche Scientifique—FNRS. I would like to express my heartfelt gratitude to my former PhD supervisors, Jan Driessen and Maria Anastasiadou, for their unwavering support. The results of this project were also enabled by the kind support of the following institutions: the CMS Heidelberg, the National Archaeological Museum Athens, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, and the Staatliche Münzsammlung Munich.

§49. Bibliography

Anastasiadou, M. 2011. The Middle Minoan Three-Sided Soft Stone Prism: A Study of Style and Iconography, Vol 1. Mayence.

Anastasiadou, M. 2015. “The Seals.” In Kalochorafitis. Two Chamber Tombs from the LM IIIA2–B Cemetery, ed. A. Karetsou, L. Girella, M. Anastasiadou, I. Antonakaki, A. Nafplioti, and E. Nodarou, 257—276. Studi di archeologia cretese 12. Padova.

Becker, N. 2018. Die goldenen Siegelringe der ägäischen Bronzezeit. Heidelberg.

Betts, J. H. 1989. “Seals of Middle Minoan III: Chronology and Technical Revolution.” In Fragen und Probleme der bronzezeitlichen ägäischen Glyptik. Beiträge zum 3. Internationalen Marburger Siegel-Symposium, 5.-7. September 1985, ed. I. Pini, 1—17. Corpus der minoischen und mykenischen Siegel Beiheft 3. Berlin.

Betts, J. H., and J. G. Younger. 1982. “Aegean Seals of the Late Bronze Age: Masters and Workshops,” Kadmos 21:104—121.

Blaklomer, F., ed. 2020. Current Approaches and New Perspectives in Aegean Iconography. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Boardman, J. 1970. Greek Gems and Finger Rings. Early Bronze Age to Late Classical. London.

Crowley, J. 2024. IKON. Art and Meaning in Aegean Seal Images. Heidelberg.

Drakaki, E. 2005–2006 (2009). “The Ownership of Hard Stone Seals with the Motif of a Pair of Recumbent Bovines from the Late Bronze Age Greek Mainland: A Contextual Approach,” Aegean Archaeology 8:81—93.

Dubcová, V. 2020. “Bird-demons in the Aegean Bronze Age: Their Nature and Relationship to Egypt and the Near East.” In Blakolmer 2020:205—222.

Effenterre, H. van. 1980. Le palais de Mallia et la cité minoenne. Étude de synthèse 2. Rome.

Evans, A. J. 1935. The Palace of Minos: a Comparative Account of the Successive Stages of the Early Cretan Civilization as Illustrated by the Discoveries at Knossos 4.2: Camp-Stool Fresco, Long-Robed Priests and Beneficent Genii; Chryselephantine Boy-God and Ritual Hair-Offering; Intaglio Types, M.M. III-L.M. II, Late Hoards of Sealings, Deposits of Inscribed Tablets and the Palace Stores; Linear Script B and its Mainland Extension, Closing Palatial Phase; Room of Throne and Final Catastrophe. London.

Evely, D. 1993. Minoan Crafts, Tools and Techniques. An Introduction. Gothenburg.

Hallager, E. 1985. The Master Impression: A Clay Sealing from the Greek-Swedish Excavations at Kastelli, Khania. Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology 69. Gothenburg.

Hallager, E. 1996. The Minoan Roundel and other Sealed Documents in the Neopalatial Linear A Administration. Liège.

Iliopoulos, T. 1998. “Ζένια Μιραμπέλλου,” Archaiologikon Deltion 53 B3:880—81.

Kanta, A. 1980. The Late Minoan III Period in Crete. A Survey of Sites, Pottery, and Their Distribution. Gothenburg.

Karetsou, A. 1978. “Τὸ ἱερὸ κορυφῆς Γιούχτα,” Praktika tes en Athenais Archaiologikes Etaireias 1978:232—258.

Knappet, C. 2020. Aegean Bronze Age Art. Meaning in the Making. Cambridge.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2005a. Aegean Seals. An Introduction. London.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2005b. “Travellers’ Tales: The Circulation of Seals in the Late Bronze Age Aegean.” In Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Proceedings of the 10th International Aegean Conference Athens, Italian School of Archaeology, 14–18 April 2004, ed. R. Laffineur and E. Greco, 767—775. Aegaeum 5. Liège and Austin.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2011. “Seals and Society in Late Bronze Age Crete.” In Πεπραγμένα Ι΄ Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου, Χανιά, 1–8 Οκτωβρίου 2006, A1, ed. M. Andreadaki-Vlazaki and E. Papadopoulou, 437—448. Chania.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2012. “Worn to Impress? Symbol and Status in Aegean Glyptic.” In Kosmos: Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 13th International Aegean Conference University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21–26 April 2010, ed. M.-L. Nosch and R. Laffineur, 739—747. Aegaeum 33. Leuven and Liège.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2020a. “A Traveller Through Time and Space: The Cut Style Seal from the Megaron at Midea.” In Neoteros. Studies in Bronze Age Aegean Art and Archaeology in Honor of Professor John G. Younger on the Occasion of his Retirement, ed. B. Davis and R. Laffineur, 155—167. Aegaeum 44. Leuven.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2020b. “Changing Views of Style and Iconography in Aegean Glyptic: A Case Study from the Cabinet des Médailles in Paris.” In Blakolmer 2020:253—271.

Krzyszkowska, O. 2022. “On the Wings of Birds: Reflections on the Cut Style in Minoan Glyptic.” In Kleronomia: Legacy and Inheritance. Studies on the Aegean Bronze Age in Honor of Jeffrey S. Soles, ed. J. M. A. Murphy and J. E. Morrison, 85—94. PM 61. Philadelphia.

Müller, W., 1995. “Bildthemen mit Rind und Ziege auf den Weichsteinsiegeln Kretas. Überlegungen zur Chronologie der Spätminoischen Glyptik.” In Sceaux minoens et mycéniens: IVe symposium international, 10-12 septembre 1992, Clermont-Ferrand, ed. I. Pini and J.-C. Poursat, 151—167. Berlin.

Onassoglou, A. 1985. Die “Talismanischen” Siegel. Berlin.

Palmer, J. L. 2014. An Analysis of Late Bronze Age Aegean Glyptic Motifs of a Religious Nature, PhD diss. University of Birmingham.

Pini, I. 1980. “Kypro-ägäische Rollsiegel. Ein Beitrag zur Definition und zum Ursprung der Gruppe,” Jahrbuch des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts 95:77—108.

Pini, I. 1995. “Bemerkungen zur Datierung von Löwendarstellungen der spätminoischen Weichsteinglyptik.” In: Sceaux minoens et mycéniens: IVe symposium international, 10-12 septembre 1992, Clermont-Ferrand, ed. I. Pini and J.-C. Poursat, 193—207. Berlin.

Pini, I. 2000. “Das Bildthema der zwei gelagerten Rinder.” In Minoisch-mykenische Glyptik: Stil, Ikonographie, Funktion. V. Internationales Siegel-Symposium Marburg, 23.-25. September 1999, ed. I. Pini, 245—255. Berlin.

Pini, I. 2010. “Soft Stone versus Hard Stone Seals in Aegean Glyptic: some Observations on Style and Iconography.” In Die Bedeutung der minoischen und mykenischen Glyptik. VI. Internationales Siegel-Symposium des CMS Marburg, 9.–12. Oktober 2008, ed. W. Müller, 325–339. Mayence.

Rupp, D. W., and M. Tsipopoulou. 2012. “Priestess? at Work: a LM IA Chlorite Schist Lentoid Seal from the Neopalatial Settlement of Petras.” In Petras, Siteia. 25 Years of Excavations and Studies. Acts of a Two-Day Conference Held at the Danish Institute at Athens, 9–10 October 2010, ed. M. Tsipopoulou, 305—314. Åarhus.

Sakellaraki, E. 2017. “Ανασκαφή Ζωμίνθου,” Praktika tes en Athenais Archaiologikes Etaireias 2017:301—448.

Sakellarakis, Y., and E. Sapouna-Sakellaraki. 1997. Archanes. Minoan Crete in a New Light. Athens.

Sapouna-Sakellaraki E., and Y. Sakellarakis. 1988. “Αρχάνες,” To Ergon tes Archaiologikes Etaireias 1988:156—160.

Sbonias, K. 1995. Frühkretische Siegel. Ansätze für eine Interpretation der sozial-politischen Entwicklung auf Kreta während der Frühbronzezeit. Oxford.

Sherrat, S. 2008. “Vitreous Materials in the Bronze and Early Iron Ages: Some Questions of Values.” In Vitreous Materials in the Late Bronze Age Aegean, ed. C. M. Jackson and E. C. Wager, 209—232. Sheffield Studies in Aegean Archaeology 9. Oxford.

Stocker, S. R., and J. L. Davis. 2016. “The Lord of the Gold Rings: The Griffin Warrior of Pylos,” Hesperia 85.4:627—655.

Warren, P. 1980-81. “Knossos: Stratigraphical Museum Excavations, 1978–1980. Part I,” Archaeological Reports 27:73—92.

Warren, P. 1982-83. “Knossos: Stratigraphical Museum Excavations, 1978–82. Part II,” Archaeological Reports 29:63—87.

Warren, P. 2010. “The Absolute Chronology of the Aegean circa 2000 B.C.-1400 B.C. A Summary.” In Die Bedeutung der minoischen und mykenischen Glyptik: VI. Internationales Siegel-Symposium aus Anlass des 50 jährigen Bestehens des CMS, Marburg, 9.-12. Oktober 2008, ed. W. Müller, 383—394. Berlin.

Wolf, D. Forthcoming 2024a. “Ariadne’s Dance—Staging Female Gesture in Neopalatial Soft-Stone Glyptic.” In Gesture, Stance, and Movement. Communicating Bodies in the Aegean Bronze Age, ed. U. Günkel-Maschek, C. Murphy, F. Blakolmer, and D. Panagiotopoulos. Heidelberg.

Wolf, D. Forthcoming 2024b. Late Minoan Representation Soft Stone Seals. Chronology, Contexts, Craft, and Cognition. Louvain-la-Neuve.

Younger, J. G. 1983. “Aegean Seals of the Late Bronze Age: Masters and Workshops II. The First-Generation Minoan Masters,” Kadmos 23.1:38—64.

Younger, J. G. 1986. “Aegean Seals of the Late Bronze Age: Stylistic Groups V. Minoan Groups Contemporary with LM IIIA1.” Kadmos 25.2:119—140.

Younger, J. G. 1991. A Bibliography for Aegean Glyptic in the Bronze Age. Berlin.

Younger, J. G. 2000. “The Spectacle-Eyes Group: Continuity and Innovation for the First Mycenaean Administration at Knossos.” In: Minoisch-mykenische Glyptik: Stil, Ikonographie, Funktion. V. Internationales Siegel-Symposium Marburg, 23.–25. September 1999, ed. I. Pini, 347—360. Berlin.

Yule, P. 1981. Early Cretan Seals. Mayence.

Footnotes

[1] On sphragistic use, cf. references in Younger 1991:94—95; further Hallager 1996.

[2] Krzyszkowska 2005a:21—22; 2011; 2012.

[3] Krzyszkowska 2012:739.

[4] Yule 1981; Sbonias 1995; Anastasiadou 2011.

[5] Onassoglou 1985; Becker 2018.

[6] Most recently: Crowley 2024.

[7] Dates after Warren 2010:393.

[8] Krzyszkowska 2005a:83—85.

[9] Evans 1935:484—485.

[10] Boardman 1970:48.

[11] An example of this practice is the selective way that soft-stone seals are mentioned and extensively discussed, while others are glanced over in the reports on the excavations of the Knossos Royal Road; cf. Warren 1980—81; 1982—83.

[12] E.g. in Iliopoulos 1998:881.

[13] Krzyszkowska 2005b:773—774; 2011:439. An exception are the early articles by J. G. Younger (1983, 1986), who provided the first overview of the material, and later case studies of iconographic groups by Pini (1995, 2010) and Müller (1995).

[14] Boardman 1970:48; Betts and Younger 1982:120; Krzyszkowska 2005a:20.

[15] Krzyszkowska 2005a:20. Cf. further, p. 124, “[..] soft stone engravers often imitated stylistic features of hard stone seals and metal signet rings, they also drew on much the same iconographic repertoire.”

[16] Betts 1989:15.

[17] This included, in 2021, The National Archaeological Museum Athens, the Heraklion Archaeological Museum, the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Antikensammlung, and, in 2022, the Staatliche Münzsammlung München; further the seals of the Sissi Archaeological Project (2019). I warmly thank these institutions and their representatives for giving me the opportunity to study the originals, despite the many restrictions caused by the covid-19 pandemic.

[18] Pini 2010:325.

[19] Tools and techniques of seal engraving: Evely 1993.

[20] Parameters for identifying style include: (1) depth and thickness of engraving; (2) depth and modeling of details; (3) drill use; (4) shapes of individual elements; (5) ratio of motif size to free space; (6) scaling; (7) poses.

[21] On the Cut Style: Krzyszkowska 2020a; 2022.

[22] Younger 1986; 2000.

[23] Anastasiadou 2015:262—263 figure 9.4a.

[24] This phenomenon occurred sporadically in the Protopalatial period (cf. Anastasiadou 2011:45—46). The same accounts for the Neopalatial and FP soft-stone repertoire, which includes only few soft-stone seals engraved in the hard-stone technique (e.g. the LM I seal in Figure 1a or the LM III seal Heraklion Museum no. 2540, cf. Anastasiadou 2015:262—263, 433 pl. XI).

[26] Further soft-stone deer: CMS I no. 499; II4 no. 140.

[27] Poses: cf. Wolf forthcoming 2024b, Chapter 5.4.1.

[28] CMS II3 no. 279, a Cypro-Aegean hematite cylinder seal from Palaikastro engraved in the hard-stone technique could be considered a possible exception. It is only marginally related to the seals under discussion, based 1. on the seal-shape, an outlier in the Aegean repertoire related to Asia Minor glyptic, and 2. on stylistic accounts, discussed in more detail by Pini 1980: 81 C5, 101; Dubcová 2020:215. Cf. Pini 1980 on Cypro-Aegean cylinder seals; Dubcová 2020 on bird-human hybrids in their possible origins in Egypt and the Asia Minor. I thank the anonymous reviewer for referring this seal to me.

[29] Cf. the description in CMS VS1A, p. 113.

[30] On terminological and identificatory difficulties viz. Bronze Age vitreous materials: Sherratt 2008:209—210. On engraved glass seals in LM II–III: Krzyszkowska 2005a:198.

[31] The iconographic groups are discussed in Wolf forthcoming 2024a.

[32] The iconography of the latter is discussed extensively by J.L. Palmer 2014:252—256.

[33] A clear LM IA horizon is present in a Type 3 soft-stone from a Neopalatial building in Petras, cf. Rupp and Tsipopoulou 2012. The prevalent style of the seals (Delineated Style) can be found in a large number of LM IA seals but appears to have lasted into at least LM IB-early, cf. Wolf forthcoming 2024b, chapter 6.3.1.

[34] Cabinet des Médailles no. M6621, cf. Krzyszkowska 2020b, fig. 1.

[35] Krzyszkowska 2005a:129 fig. 219.

[36] See Figure 14 for a comparison of the median diameters and thicknesses of soft-stone and hard-stone lentoid seals covered in this study.

[37] Knossian examples were found in the Unexplored Mansion, House of the Frescoes, Gypsum House, and House of the Ivories (Heraklion museum nos. 2094, 2995, 3190; CMS II3 no. 17; II4 no. 111). The Malia specimen (CMS II4 no. 165) is from Quartier Epsilon, the Archanes seal from a possible sanctuary, (Sakellarakis and Sapouna-Sakellaraki 1997:696). Distribution is discussed in detail in Wolf forthcoming 2024b, chapter 6.4.2.

[38] Previously discussed by Pini 1995:198—199 as “Chimära-Typus”.

[39] Further CMS VI no. 267; and X no. 264.

[40] Wolf forthcoming 2024b, chapter 6.3.1.

[41] Sapouna-Sakellaraki and Sakellarakis 1988:159; Sakellaraki 2017:379—380, fig. 35; van Effenterre 1980:572—574, fig. 847; Karetsou 1978:255 Pl. 169 γ–δ; Pini 1995:199 n. 3; Kanta 1980:32; Pini 2010:338 n. 46.

[42] Knappett 2020:89—90; Krzyszkowska 2005a:235—236.

[43] Pini 2000; Drakaki 2005–2006 (2009).

[44] Krzyszkowska 2005a:124.

[45] Krzyszkowska 2005a:236.

[46] Stocker and Davis 2016.

[47] Stocker and Davis 2016:640—643.

[48] https://www.heraklionmuseum.gr/en/exhibit/the-ring-of-minos/ (accessed 2024-06-02).

[49] Hallager 1985. I thank the anonymous reviewer for this observation.

[50] Cf. above, n. 14.

For a discussion of this and the other ECRs’ papers, go the MASt Summer 2024 report landing page and scroll to §166