MASt – Summer Seminar 2022: Summaries of Presentations and Discussion

§1.1. Rachele Pierini opened the Summer session of the MASt seminars by presenting the different structure of the July event, which hosted the mentor(s) and mentee session. During the meeting, graduate students presented their thesis along with their mentors. Specifically, the mentees were Cassandra Donnelly, Jared Petroll, and Jennifer Lowell.

§1.2. Roger Woodard acted as co-organizers of the Summer 2022 MASt mentor(s) and mentee seminar along with Rachele Pierini and Tom Palaima and, in addition, coordinated the session. Moreover, Woodard chaired the Summer 2022 MASt seminar.

§2. Donnelly presented her PhD dissertation on Cypro-Minoan script signs and the relationship between writing and trade in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean. Petroll shared insight from his work on apiculture in the Aegean Bronze Age. Lowell focused her MA thesis on the lozenge and offered diachronic perspectives on the interaction between syllabic/alphabetic signs and logographic signs by examining the multivalent representation of the Chi in Early Medieval Insular manuscripts.

§3. Substantial discussions followed each presentation. Specifically, contributions to the seminar were made by Janice Crowley (see below at §§27.1; 100), Cassandra Donnelly (§§25.2—25.3; 26.2; 27.2; 28.2; 28.4; 29.2; 29.4; 30.2; 103.1), Nicolle Hirschfeld (§26.1), Hedvig Landenius Enegren (§§101.1; 103.2), Jennifer Lowell (§§98.2; 98.4—98.5), Tom Palaima (§§25.1; 104.1), Vassilis Petrakis (§§29.1; 29.3; 102), Jared Petroll (§§99.2; 101.2; 104.2), Rachele Pierini (§§30.1; 99.1), Malcolm Wiener (§§28.1; 28.3; 28.5; 31), Roger Woodard (§§98.1; 98.3).

Topic 1: Presenting ‘Signs of Writing? Writing and Trade in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean’: PhD dissertation presented by Cassandra Donnelly, defended on October 15, 2021, at the University of Texas; supervisor: Thomas G. Palaima; second supervisor: Nicolle Hirschfeld

Presenter: Cassandra Donnelly (cmdonnelly@utexas.edu)

§4. As part of the MASt mentor/mentee seminar, my presentation aimed to solicit feedback on directions for future research after the completion of my dissertation. To that end, I presented a summary of my dissertation Signs of Writing? Writing and Trade in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean (supervisor: Thomas G. Palaima), my publications during and since my dissertation defense (Donnelly 2021b), and the directions of my current research. I finished the presentation by discussing three objects that epitomized the ongoing difficulties presented by the material, notably, questions of terminology (writing vs. mark, literacy vs. illiteracy, etc.) and typology (what counts as a Cypro-Minoan inscription, for instance). The presentation was followed by a fruitful question and answer session, reported below at §§25.1—31. I began the presentation with an overview of the state of knowledge regarding the Cypro-Minoan script, which has seen a relative fluorescence of attention in the past two decades.

Figure 1. Map of the distribution of scripts in the Eastern Mediterranean during the Late Bronze Age. Map drawn by author, outline adapted from Knox 2012:17.

§5. The Cypro-Minoan script is unlike the other Aegean scripts in its chronological and geographical breadth (see Figure 1). It overlaps chronologically with both Linear A and Linear B and is the only “Aegean” script to have survived the Late Bronze Age collapse (ca. 1180 BCE; see Figure 2). Cypro-Minoan was likely derived from Linear A, but both the archaeological and textual evidence of Cretan-Cypriot contact during the period of script transmission (ca. 1525 BCE) is meagre. There are very few Cypro-Minoan texts from the first two centuries of Cypro-Minoan script use in the fifteenth and fourteenth centuries, a circumstance which hinders our ability to study the process of script transmission and adaptation. Further obscuring the connection between Linear A and Cypro-Minoan is the fact that Cypro-Minoan inherited a rough 60% of Linear A signs (depending on one’s count)[1] and jettisoned the ideograms, the only Aegean script to have done so. Cypro-Minoan signs are sometimes drawn into clay with a bladed implement, the dominant method of rendering signs in Linear A and Linear B texts, but at other times their components are impressed or “punched” into clay in a manner more like cuneiform wedges but made with a round-tipped stylus. The majority of Cypro-Minoan texts date to the LCIIC and LCIII periods, overlapping with the heyday of Linear B, but there is no suggestion of contact between the two scripts, whether in the textual, geographical, or archaeological record. The Cypro-Minoan script was written locally at Tiryns (Vetters 2011, Donnelly 2022), but only after the collapse of the Tyrinthian palace and the concomitant abandonment of Linear B.

Figure 2. Chronological chart indicating the appearance and disappearance of Aegean scripts in the Late Bronze Age. The placement of grey text in each box reflects the approximate absolute date in which the given script went into or out of use. Chart created by author, with outline adapted from Hesse 2008:3, fig. 1.1.

§6. Cypro-Minoan is the only Aegean script written locally in both the Levant and the Aegean. This observation is fundamental to the distinctiveness of the Cypro-Minoan, the only Aegean script for which we have evidence of its use in trade contexts. The Cypro-Minoan script frequently appears on mercantile objects. Whereas the use of Linear B is most certainly linked to administrative centers, and the use of Linear A to administrative centers and ritual settings, Cypro-Minoan lived a life of the sea. It is true that a small number of Linear A texts did travel, and that Linear A was likely produced locally outside of Crete in the Cyclades and at Samothrace. The stray finds of Linear A in the Levant, however, show no evidence of being made locally and are all one-off imports (Finkelberg et al. 2004; Karnava 2004). Linear A went where “Minoans” settled. Cypro-Minoan went where “Cypriots” conducted trade and was then used locally in those places, albeit in small amounts, in the case of Tiryns and Ugarit.

§7. The relationship between Cypro-Minoan and Levantine cuneiform scripts has been hotly debated and at times overstated. The Cypro-Minoan texts at Ugarit, most of which, if not all, appear to be locally produced (for a contrasting view, see Ferrara and Bell 2016), are influenced by local writing practices in their writing medium. Four of the twelve Cypro-Minoan texts from Ugarit are clay tablets, three of which are thought to be administrative based on the presence of numerals (##213, ##214) and a list (##215). Clay administrative tablets are incredibly common at Ugarit in both Akkadian cuneiform and alphabetic cuneiform, aka “Ugaritic”, but totally absent from Cyprus, where only six clay tablets have been discovered, none of which contains numerals (##001, ##207-##209, and the still unpublished ADD##256-257).

§8. The discoveries of clay tablets at Ugarit in the 1950s initiated a debate over whether and to what extent Cypro-Minoan text underwent a process of “cuneiformization”. It was argued that the linear and drawn character of the signs was replaced by their impressed or “cuneiformized” sign-rendering under the influence of cuneiform (for a critique and bibliography, see Palaima 1989). The recent PhD work of Martina Polig shows that the dichotomy of “impressed” vs. “drawn” signs is not as stark as previously thought (Polig 2022). Polig undertook a close paleographic study of the Cypro-Minoan texts based on 3-D models of around 75% of the Cypro-Minoan corpus. Polig’s models are constructed from sophisticated laser scans of the Cypro-Minoan texts. Polig’s finely detailed models of the texts show that the majority of texts combine drawn and impressed techniques to render individual signs, and that neither method on its own is dominant. It is certainly possible that the aesthetics of the Cypro-Minoan script was inspired by or developed in response to cuneiform, but there is no evidence that the actual technique of rendering impressed signs was under the influence of cuneiform practice.

§9. The history of Cypro-Minoan scholarship is divisible into two periods with two different approaches to classifying a text as Cypro-Minoan, the pre- and post-corpora periods (1870-2007, and 2007-present, respectively). In the pre-corpus period, any text with a Cypro-Minoan script sign was regarded as an inscription, regardless of whether the text contained only a single sign or multiple signs. Single sign texts were excluded from both corpora, however, starting with Jean-Pierre OIivier’s HoChyMin and continuing into Silvia Ferrara’s CM II corpus, single-sign texts were excluded from the corpora (see Ferrara 2012:18 for four notable exceptions). The decision to exclude single-sign texts from the corpora is consequential for how we understand the sociohistorical context of writing in Cyprus, who the writers were and what they were using writing for.

§10. Olivier’s choice to exclude single-sign texts was in response to the sheer number of single-sign texts, over 1000, and a desire to keep the corpus project manageable (HoChyMin:36). For Ferrara, the decision was ideological, a matter of what counts or does not count as writing. Ferrara rejects the single-sign texts on the grounds of their ambiguity, believing that a single-sign text can just as likely record a linguistic feature (i.e., be writing) as a non-linguistic one (i.e., be a mark). A single-sign text, she argues, can only be shown to be writing provided we have sufficient archaeological data to contextualize the text in literate settings. She asserts that we lack sufficient data to make such determinations in most every instance (Ferrara 2012:18). As I show in my dissertation, however, it is possible to show that the single-sign texts come from literate contexts. Olivier and Ferrara’s exclusion of the single-sign texts from the corpora essentially relegated all single-sign texts to marks, even though a proper study of the question had yet to be undertaken.

§11. The Cypro-Minoan corpus, as currently constituted in Ferrara’s CM II, consists of 244 inscriptions. The corpus reveals a script with a unique profile. Many of its writing media are unattested in the other scripts of the region and almost none of the writing is administrative. The majority of the inscriptions were written at a single site on Cyprus, Enkomi, though a portion of texts from within and outside of Cyprus suggest a connection to overseas trade. The script recorded in the corpora is almost hyper local in its uses and profile.

§12. About 30% of the corpus consists of small clay balls approximately 2cm in diameter, a writing medium unattested outside of Cyprus. All but five of the 90 clay balls come from Enkomi. Of the five non-Enkomi balls, four come from the neighboring sites of Hala Sultan Tekke (2) and Kition (2), and one comes from Tiryns and is likely made of local Tirynthian clay (Vetters 2011:18). So the balls are otherwise hyper local, their production tied almost exclusively to a single site on Cyprus but the Tiryns ball being made locally subverts that picture. In contrast to the balls, the vessel texts, which account for another 30% of the corpus, have associations with overseas trade (Hirschfeld 2004). They are found at every site where Cypro-Minoan has been found outside of Cyprus (see Figure 1). The rest of the corpus consists of texts on a miscellany of writing media, including cylinder seals, metal bowls, jewelry, and more. Clay tablets (12) comprise less than 1% of the corpus.

§13. The single-sign texts excluded from HoChyMin and CM II are much more numerous than the number of texts in the corpus, numbering at minimum 2000. This number includes both single-sign texts with script signs and non-script signs. The vast majority of single-sign texts are vessel texts (often referred to as potmarks in Cypro-Minoan literature; for their definitive study see Hirschfeld 1999), with smaller numbers of texts appearing on copper ingots (full size and miniature), tin ingots, lead ingots, copper tools, cylinder seals, architectural blocks, anchors, loom weights, and more. If the single-sign texts are regarded as Cypro-Minoan writing, then the script can no longer be described as hyper-local and the vessel texts, with their wider geographic reach and connections to trade, become the Cypro-Minoan writing medium par excellence.

§14. The profile of Cypro-Minoan changes according to whether the single-sign texts are considered part of the script. The Cypro-Minoan of the multi-sign texts, embodied in the clay balls, is an idiosyncratic, Cyprus-based script whose use is concentrated at the site Enkomi. Cypro-Minoan inclusive of the single-sign texts is best represented by the vessel texts, a script found on mercantile objects in use throughout the Eastern Mediterranean at the sites where Cyprus’s trade connections were tightest (Ugarit and Tiryns). The stark differences in profile between pre-and post-corpus Cypro-Minoan raise vital questions about the nature and extent of literacy in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean and the role of traders in the use and transmission of script. The conflicting pre- and post-corpus approaches to Cypro-Minoan and the post-corpus material itself put our understanding of Cypro-Minoan and its writers at an impasse.

§15. My dissertation aimed to loose this impasse, by establishing the bounds of Cypro-Minoan script use and literacy through a case study of the vessel texts. I chose the vessel texts as my case study because of the relatively large number of both single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts. I compared the material features of the single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts to one another to assess whether the texts were made in the same literate contexts. I concluded that both multi-sign and single-sign texts were, on the whole, written by literate persons participating in the same mercantile institutions. This statement is true even when the script signs in single-sign texts were being used as part of a marking system, i.e., were not being used to convey linguistic content. I conclude that the Cypro-Minoan script was visible to non-literate as well as literate viewers and that the Cypro-Minoan script was written locally at Tiryns and Ugarit, where we find small numbers of multi-sign vessel texts but large numbers of single-sign vessel texts.

§16. I rooted my dissertation’s argumentation on a complementary theory, “scriptworlds,” and method, diplomatics, drawn from the fields of world literature and archival studies, respectively. The theory of scriptworlds and the method of diplomatics treat script and writing as comprised not exclusively of script signs, but also of the attendant material practices related to a given script’s use. This wider conception of writing circumvents the impasse caused by the pre- and post-corpus approaches to Cypro-Minoan, which define a text as writing based solely on the presence or absence of a certain number of script signs. Instead, a piece of writing belongs to a scriptworld not only if the script is present, but also if the text-bearing object’s material features match those of other texts. Is the text-bearing object made of the same material as other texts? Was the same or a similar writing implement used to make it? Does its use of punctuation and paleography fit other texts? This holistic way of looking at texts is not new in the field of Aegean scripts, where attention to the material features of texts has been central to the identification of scribal hands (for just one example, see Driessen 1999), but it had not been applied to the single-sign texts as a way of discerning whether they were made by the same people who made the multi-sign texts, i.e., whether the single-sign texts were produced in literate contexts.

§17. According to scriptworlds, a theory developed by David Damrosch, a “script” is more than just signs of writing but is a “package” or “scriptworld”, consisting of script signs, the institutions in which the script is taught, and the specific material practices supported by the script’s institutions (Damrosch 2007). Diplomatics is a branch of archival studies and Information Sciences developed in the Middle Ages in response to the need to authenticate archived contracts (Duranti 1998). Diplomatics likewise conceives of texts as comprised of not only the signs on a page but also the material features of the text-bearing object. A diplomatics study identifies a text as coming from the same institutions as other contemporary texts according to the physical features of the text-bearing object, including but not limited to the material features of its writing medium, writing implement, formatting and punctuation practices, and paleography. In the diplomatic method, texts with the same material features are treated as belonging to the same “document form” and are believed to originate from the same institutional and sociocultural contexts. This is true regardless of the content of the text itself. The focus of diplomatics on the material features of texts is particularly convenient in the case of an undeciphered script like Cypro-Minoan. The diplomatic conception of a text framed the approach I took to the single-sign vessel texts in my dissertation. Instead of asking whether a text has a script sign and is writing, I studied the material features of single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts to ask whether the texts were the same document form and therefore were part of the same scriptworld.

§18.1. My dissertation consists of five chapters, which together assess the extent of the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld. The chapters are:

- Chapter One: Single-Sign Texts in the Study of Cypro-Minoan

- Chapter Two: Vessel Texts from the Eastern Mediterranean

- Chapter Three: The Diplomatics of Single-Sign and Multi-Sign Texts

- Chapter Four: Punctuation and Sign Use

- Chapter Five: Cypro-Minoan Texts Abroad

§18.2. Chapter One presents an overview of the pre- and post-corpus approaches to single-sign texts and the various definitions of writing employed in Cypro-Minoan studies. Chapter Two provided an overview of vessel-writing and vessel-marking practices in the Eastern Mediterranean and identified the distinctive material features of vessel-writing and vessel-marking practices of the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld. Chapter Three compared the material features of single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts, showing that both the single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts should be regarded as the same document form deriving from the same institutional setting. The same people who made the multi-sign texts also made the single-sign texts. The single-sign texts should therefore be regarded as products of a literate environment. Chapter Four compared the content of the single-sign and multi-sign vessel texts to show that they both employ the same limited sign repertoire. It is therefore likely that the texts share the same referents, and that the single-sign texts should be viewed as writing. Chapter Five broadens its purview from the vessel texts to the body of Cypro-Minoan texts from outside of Cyprus. The chapter concludes that Cypro-Minoan was written locally at Tiryns, where the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld was established wholesale, and Ugarit, where the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld underwent creative changes. At Ashkelon, where at least one Cypro-Minoan text has been recovered, the Cypro-Minoan script seems to have been divorced from its scriptworld. On at least two documents from Ashkelon, we find signs of the Cypro-Minoan script or signs likely derived from the Cypro-Minoan script, but on text-bearing objects whose material features to do not fit the document forms of the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld. Overall, my dissertation shows Cypro-Minoan to be the script of the single-sign texts, a well-traveled script in relatively wide circulation on mercantile objects, and firmly puts the ability to write and create texts in the hands of traders.

§19. I published four articles and chapters during and shortly after my dissertation: Donnelly 2020; Donnelly 2021a; Donnelly 2022; Donnelly forthcoming. Two of these publications reproduce or rewrite portions of the dissertation. Donnelly 2022 reprises an argument made in Chapter Five of my dissertation, that the Cypro-Minoan material from Tiryns was made locally and is part of the Cypro-Minoan scriptworld. Donnelly (forthcoming) is an important contribution to the study of Cypro-Minoan, drawing on material presented in Chapter Four of my dissertation. Here, I argue for interpreting the single signs in certain single-sign and multi-sign texts as word abbreviations and show that not every two-sign text in Cypro-Minoan should be read as a poly-syllabic word but that some are two-sign abbreviations. I published parts of my dissertation in the form of chapters and articles because I do not want to publish a traditional dissertation monograph that reproduces a refined version of the dissertation. Instead, I want to write a monograph about the way that traders used the Cypro-Minoan script in the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean during and after the “collapse”. I am broadening the dissertation’s focus on vessel texts to include other text-bearing mercantile objects, such as copper tools, metal ingots, anchors, and so on.

§20. To end my presentation, I present three text-bearing objects that represent my current areas of inquiry and the ongoing questions I have in my study of Cypro-Minoan. Here, I will present only one of these objects, in a move to obey copyright restrictions and keep this written report to a concise length (see Figure 5). The object, copper ingot BM 1897,0401,1535, encapsulates much of what is frustrating and joyful in my ongoing study of Cypro-Minoan. Ingot BM 1897,0401,1535 is a copper ingot that was “excavated” by the 1897 Turner Bequest Excavations as part of the Foundry Hoard (Crewe 2007). The ingot is currently housed at the British Museum. The image of the ingot produced here, along with its bibliography, is available free online for your perusal here [https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/G_1897-0401-1535] thanks to the efforts of the British Museum’s Department of Greece and Rome. The copper ingot bears a single Cypro-Minoan script sign, CM 027, either stamped or molded into the metal, centered at the top of the ingot in between its two arms. I end this report with a short list of the challenges the ingot poses for me and my work, which are representative of my current lines of inquiry.

Figure 3. Ingot BM 1896,0401,1535. Photograph from the British Museum website, drawing by author.

Literacy of the writer

§21. Is the person who put the script sign on this ingot a writer trained in the Cypro-Minoan script? A study of the ingot suggests that the script sign was either part of the ingot’s mold or stamped into the ingot while still hot (Catling 1964:267). In either case, its maker would have been a craftsperson. Would the craftsperson have been able to write more script signs than just this one here, or was it a commission made by a literate person perhaps drawn from a sketch? If the craftsperson was not a writer of the script, where would the writer have been during the craft production process? What do any of these scenarios say about the social context of writing on Cyprus? At minimum, we can say that the process of stamping the sign on the ingot or drawing the sign into an ingot mold would have entailed numerous people interacting with Cypro-Minoan writing. In all likelihood, the people involved would have had varying knowledge of and relationships to the script. What is the best way to describe the different types of literacy of the people involved in making the ingot?

Questions of audience

§22. The ingot’s sign was placed on a visible part of the ingot, centered on the object, and clearly impressed. The text was clearly visible and not hidden. Who was the intended audience? Was a specific audience intended or a general one? During the ingot’s production and subsequent life as a trade object, numerous people with varying relationships to the script would have interacted with the script sign on the ingot, from the person(s) who commissioned and made the text to a person tasked with moving the ingot from one building to another. It is likely that people who were not trained in how to read or write the script would have interacted with the ingot. In this sense, the ingot text is not unique. There are lots of other mercantile objects bearing visible Cypro-Minoan signs. For instance, many vessel texts are on visible parts of the vessels. Many of the vessels in question were not fancy or elite vessels, but prosaic vessels used within Cyprus and in overseas trade. Most vessels were not found in elite or restricted settings. The vessels and their signs, much like the ingot, would have been visible to many different sets of eyes, some trained in script and some not. Writing on Cyprus was certainly not hidden. What did the signs mean to the people who were trained in how to read them? And to those who were not?

Characterization of script use

§23. What is the best way to characterize the use of script on the ingot? The ingot is one of the very few ingots bearing a stamped or impressed text with a script sign. Whatever information the text conveys, it was likely not integral information about the ingot, its trade value, or its qualities. If any of this were the case, we would expect to find more text-bearing ingots and we would expect the texts themselves to be somewhat standardized. Even if the ingot text does not record mercantile information about the ingot, the ingot itself is undeniably a trade object. I would classify the ingot text as coming from a trade context, but the text itself as non-mercantile in nature. If the text is non-mercantile, what is its function? The Cypro-Minoan texts on ingots have sometimes been interpreted as “owner’s marks” (Galili et al. 2013). But isn’t this term a bit misleading? Ingots circulated widely and their raison d’être was to be melted down and transformed, their texts lost in the process. The concept of ownership with its connotations of inviolable personal property does not fit here. If the texts were meant to be seen and circulate widely in trade contexts, could they be thought of as a type of branding? If so, wouldn’t we expect to see many more texts than the few surviving ones? How do we characterize the use of script on the ingot?

Donnelly’s Bibliography

Catling, H.W. 1964. Cypriot Bronzework in the Mycenaean World. Oxford.

CM II = Ferrara, S. 2013. Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions: Volume 2: The Corpus. Oxford.

Crewe, L. 2007. “From lithograph to web: the British museum’s 1986 Enkomi excavations.” Κυπριακή Αρχαιολογία Τόμος V. Archaeologia Cypria, Volume V.

Damrosch. 2007. “Scriptworlds: Writing Systems and the Formation of World Literature.” Modern Language Quarterly68 (2):195–219.

Donnelly, C. M. 2020. “Signs, Marks, and Olivier Masson in the Development of the Cypro-Minoan Corpus.” Cahiers Du Centre d’Etudes Chypriots 50:91–108.

Donnelly, C.M. 2021a. “Repetition, Sortition, and Abbreviations in the Cyprio-Minoan Script.” In Repetition, Communication, and Meaning in the Ancient World, ed. D. Beck, 93–118. Leiden—Boston.

Donnelly, C. M. 2021b. “Signs of Writing? Writing and Trade in the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean.” PhD Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Donnelly, C. M. 2022. “Cypro-Minoan Abroad, Cypriots Abroad?” Athens University Review of Archaeology 9:195–206.

Donnelly, C. M. (forthcoming), “Cypro-Minoan and Its Potmarks and Vessel Inscriptions as Challenges to the Aegean Scripts Corpora.” In Writing around the Ancient Mediterranean: Practices and Adaptations. Oxford.

Driessen, J. 1999. The Scribes of the Room of the Chariot Tablets at Knossos: An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Study of a Linear B Deposit. Leuven.

Duranti, L. 1998. Diplomatics: New Uses for an Old Science. Lanham, Maryland.

Ferrara, S. 2012. Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions: Volume 1: Analysis. Oxford.

Ferrara, S. and C. Bell. 2016. “Tracing Copper in the Cypro-Minoan Script.” Antiquity 90 (352):1009–1021.

Finkelberg, M. et al. 2004. “The Linear A Inscription (LACH Za 1).” In The Renewed Archaeological Excavations at Lachish (1973-1994), ed. D. Ussishkin, 3:1629–1638. Tel Aviv.

Galili, E. et al. 2013. “A Late Bronze Age Shipwreck with a Metal Cargo from Hishuley Carmel, Israel.” The International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 42:2—23.

Hesse, K. J. 2008. Contacts and Trade at Late Bronze Age Hazor: Aspects of Intercultural Relationships and Identity in the Eastern Mediterranean. Umeå.

Hirschfeld, N. 1999. “Potmarks of the Late Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean.” PhD Dissertation, University of Texas at Austin.

Hirschfeld, N. 2004. “Eastward via Cyprus? The Marked Mycenaean Pottery of Enkomi, Ugarit and Tell Abu Hawam.” In La Céramique Mycénienne de l’Egée Au Levant: Hommage à Vronwy Hankey, eds. J. Balensi, J-Y. Monchambert and S. Müller Celka, 97–104. Lyon.

HoChyMin = Olivier, J-P. 2007. Édition Holistique des Textes Chypro-Minoens. Rome.

Karnava, A. 2004. “The Tel Haror Inscription and Crete: A Further Link.” In Emporia: Aegeans in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean. Proceedings of the 10th International Aegean Conference/10e Recontre Égéenne Internationale Athens, Italian School of Archaeology, 14-18 April 2004, ed. R. Laffineur and E. Greco, 837–843. Austin—Liège.

Knox, D-K. 2012. “Making Sense of Figurines in Bronze Age Cyprus: A Comprehensive Analysis of Cypriot Ceramic Figurative Material from EC I – LC IIIA (c.2300BC – c.1100BC).” PhD Thesis, The University of Manchester.

Palaima, T. G. 1989. “Cypro-Minoan Scripts: Problems of Historical Context.” In Problems in Decipherment, eds. Y. Duhoux and T. G. Palaima, 121–188. Louvain-La-Neuve.

Polig, M. 2022. “3D Approaches to Cypro-Minoan Writing—Advanced 3D Methods of Documentation, Visualization and Analysis.” PhD Dissertation, The Cyprus Institute and Ghent University.

Valério. 2016. “Investigating the Signs and Sounds of Cypro-Minoan.” PhD Dissertation, University of Barcelona.

Vetters, M. 2011 “A Clay Ball with Cypro-Minoan Inscription from Tiryns.” Archäologischer Anzeiger 2011 (2):1–49.

Discussion following Donnelly’s presentation

§24.1. Tom Palaima opened the discussion by describing Cypro-Minoan as an “odd duck” due to its appearance, which lacks similarities with the Aegean scripts we are more familiar with (i.e. Linear A and, even more, Linear B). In this regard, he mentioned a discussion during Donnelly’s viva about potential definitions for these single-sign inscriptions and how to differentiate them from potmarks. On this basis, Palaima asked Donnelly for what criteria she used to identify these single-sign inscriptions as “texts” as opposed to other options, and how the basic notion of texts applies to single-sign objects.

§24.2. Cassandra Donnelly acknowledged that reflections surrounding the term potmarks are important—though not a focus in this particular presentation. Traditionally, the single-sign texts have been referred to as potmarks since “potmarks” is usually considered a neutral term, Donnelly continued. However, her reason for choosing another term was aligned with her focus solely on script signs, whereas potmarks refer to both scrip-signs and non-script signs—Donnelly explained. She also added that this narrowed focus encouraged direct comparison, which served to create an understanding for whether there was a relation between the single sign and multi sign vessel texts.

§24.3. On the other hand, Donnelly highlighted that there is room for exploration regarding the significant number of vessel texts with non-script signs. Donnelly therefore suggested, following Hirschfeld, that the vessel texts comprise several different marking systems, at least one of which uses signs drawn from the Cypro-Minoan script. By way of example, Donnelly mentioned the dockets, functioning as roasters, at the site of Deir el-Medina, which combine script and non-script signs to refer to workmen. These texts span hundreds of years, and with time a higher frequency of script signs gets borrowed into the marking system as more literate administrators attend to the site of Deir el-Medina, Donnelly continued. In addition, Donnelly argued for a possible analogy since texts on Cypro-Minoan vessels show evidence for a marking system (or many). However, the most important point, she stressed, is that the people who made the signs were well trained. Whether or not they used the script-signs as writing, to represent a phonetic syllable or to convey some other form of information, they were knowledgeable within the script and that, Donnelly argued, is why there are vessel texts with multi-sign texts. With this, Donnelly concluded by emphasizing that the inventory of signs in the single-sign texts is the same as the signs that are used as abbreviations in the multi-sign texts.

§25.1. Nicolle Hirschfeld stressed that there are very few tablets available. For that reason she encouraged a focus on the context and was thus happy to see Donnelly’s work. Some single-sign texts, Hirschfeld argued, reflect knowledgeable people indeed, but not all of them, which complicates the investigation. Again, Hirschfeld highlighted that a contextual focus is desirable in order to not practice circular thinking. Questions such as what sorts of items were marked counteracts circular thinking and might be helpful to find the bigger pattern, Hirschfeld concluded.

§25.2. Donnelly pointed out that many, Hirschfeld and herself included, have called for a corpus of the potmarks but none has been published thus far and this makes it difficult to identify patterns in a meaningful way. However, Donnelly stressed that her ongoing research on Canaanite jars as transport vessels will shed light on this since these vessels often contain Cypro-Minoan single sign texts. She added that, by combining the results of this case study with an array of complementary analyses (e.g. petrographic and volumetric), she hopes to gain a better knowledge about non-script signs and, eventually, to set the foundation for a corpus of single sign vessels.

§26.1. Janice Crowley opposed separating out the single-sign as not a text and argued that doing so was rather artificial. In Minoan iconography many of the Hieroglyphic signs, like the eye, are used as symbols in art and these links between text and iconography need constantly to be kept in mind.

§26.2. Donnelly seconded Crowley’s scepticism about the efficacy of excluding single-sign tests on pottery and stressed that it prevents certain understanding. At the same time, Donnelly drew attention to taking the frame and the question asked into consideration (questions like how the script was used, who was able to use it, and how integrated it was). On this basis, looking at single signs seems necessary, Donnelly concluded.

§27.1. Malcolm Wiener asked how and why Cyprus decided to adopt a script that was close with Linear A and argued that it must have to do with the metal trade and the need for copper and tin. He stressed that more would have been known if careful excavation and careful records of more sites had been kept. Nonetheless, Cypro-Minoan lasted for a long time, which made Wiener consider if there could have been a link with it as a lingua franca since there was a trade language in use in the Mediterranean with a great mix of languages within it. Could the very long use of Cypro-Minoan as it is now seen in odd places be a reflection of the acts of traders, Wiener speculated.

§27.2. Donnelly supported the analogy and posited that the script, as it appears on the vessel texts, could have been a common script used by merchants operating in the late Bronze Age East Mediterranean on analogy to a lingua franca.

§27.3. Further, Wiener brought up the existence of uninscribed balls.

§27.4. Donnelly remarked that not many uninscribed balls are known. In connection to the metal trade that Wiener mentioned, Donnelly added that there are not plentiful Minoan material remains on the island of Cyprus. One reason for this, Donnelly argued, could be that the Minoans traded goods that did not survive in the archaeological record, with metal and cloth being possible examples.

§27.5. Wiener emphasized the lack of evidence due to the careless treatment of valuable sites and, by extension, the impossibility of knowing how the language came to Cyprus.

§28.1. Vassilis Petrakis expressed interest in the possibility of literate traders and drew attention to the potential connection between the Cypriote and the Mycenaean palatial administrations, which might be hinted at by references to a man named ku-pi-ri-jo, the /Kuprios/ arguably interpreted as referring to someone who had dealings with the Cypriot polities. Given the evidence for Cypro-Minoan being actually written later at Tiryns, he asked whether Donnelly would envisage a literate administrative overlap between Cypriot and Mycenaean bureaucracies of the palatial period.

§28.2. Donnelly argued that there were two administrations on Cyprus, although it is still uncertain whether there was one or many administrations and whether it was centralized. Donnelly acknowledged that a stronger sense of the chronology of the trade is required for a better understanding of the possible connection between administrations.

§28.3. Petrakis stressed the importance of the finding of another writing system being in use in the Aegean (namely Cypro-Minoan at Tiryns). On the complex topic of the genesis of Cypro-Minoan script(s), on which evidence is not abundant, Petrakis expressed some concern that the evidence linking most clearly early Cypriot writing to the Aegean is one the single tablet 1885 (HoChyMin ##001 ENKO Atab 001) from Enkomi, assigned to the so-called “Cypro-Minoan 0” script (whose relationship to later Cypro-Minoan is problematic), and asked whether Donnelly is of the opinion that the Aegean link is supported from further early (i.e. dated before LC IIC) Cypro-Minoan inscriptions.

§28.4. Donnelly stressed that that argument most recently was put forward by Philippa Steel and mentioned that some of the signs and or sign forms from the earliest Cypro-Minoan inscriptions, especially the earliest CM 0 tablet, were never in use again.

§29.1. Rachele Pierini asked Donnelly whether she considered comparative analyses with other single-sign attestations from other Aegean scripts like Cretan hieroglyphic and whether she noticed some differences or patterns in connection with elements like chronology, geography, support, or purpose of the inscribed object.

§29.2. Donnelly explained that thus far this kind of comparison has not been carried out, although she believes that there is a tendency to overstate the differences between Cypro-Minoan and Linear A due to the limited amount of tables. Therefore, her comparison has been more connected to Linear A than to Cretan Hieroglyphic and the chronology is a difficult topic because there are many elements that are yet to be fully elucidated.

§30. Wiener concluded the discussion on a hilarious note by joking that the survival of the texts has a lot to do with whether the fire or the rain comes first.

Topic 2: Measuring ΜΕΛΙ: The Scale and Religious Significance of Apiculture in the Aegean Bronze Age

Presenter: Jared Petroll (jppetroll@utexas.edu)

Introduction

§31. Despite the large body of work that has been done on honey and apiculture in the Aegean Bronze Age, which has focused on technology, the religious uses of honey, and its use as a sweetener of fermented beverages, few investigations have been conducted on the actual scale of the industry during this period. Oftentimes, when scale is brought up in literature, the generalizing label that honey production ‘must have occurred on a large scale’ is frequent, with little stipulation as to what that means.

§32. Additionally, since honey was so often used in religious dedications, issues of apiculture’s centralization and the role of religion should be assessed. We see in the tablets instances of flocks dedicated to different gods, workshops bearing religious associations, and even deities listed as “collectors” of foodstuffs and products. Since honey possessed religious value, could it have been produced in similar contexts? If so, could this suggest more concentrated, perhaps even palatial, control over the industry, or not?

§33. Here I take some first steps at addressing these questions through a synthetic approach, looking at the Eastern Mediterranean archaeological record, the Linear B record, and the later Greek literary record. In going broad, I hope to account for gaps that might exist in any singular source of evidence or region. Taken together, one achieves a better sense of what honey production might have looked like in the Minoan-Mycenaean world: its size, centralization, and religious importance.

Part 1: The Eastern Mediterranean Comparative Materials

§34. Examining the archaeological evidence for apiculture, honey, and beeswax in the Bronze Age Eastern Mediterranean was the first part of my thesis. Namely, I looked at the uses of honey and beeswax, the different hives attested, the organization of apiculture in Egypt, and the only surviving apiary in the archaeological record. The results of these inquiries set a firm backdrop from which I could examine the Linear B and later Greek evidence.

Uses of Honey and Beeswax

§35. Some of the best evidence for the use of honey and beeswax comes from mass spectrometry and organic residue analysis. Through these, archaeologists have identified honey’s presence in a variety of contexts, giving hints regarding its use. For instance, organic residue analyses of small vessels found in a MM IA aromatics workshop at Chamalevri produced evidence of honey alongside resin, olive oil, and iris oil (Vlazaki 2010:362). This indicates that the commodity was used in perfumery (Vlazaki 2010:362).

§36. Honey was also used in the wine-storage process in the Bronze Age Aegean. At the site of Akrotiri, organic lipid analysis identified beeswax on wine pithos sherds (Karnava and Nikolakopoulou 2005:224). It is thought that the honey was applied to the internal surface of the vessel to prevent the evaporation of its contents, which was a known practice in later antiquity (Karnava and Nikolakopoulou 2005:224).

§37. Honey seems to have been an ingredient in fermented beverages that were featured in ritual drinking practices as well. The results of a 1990s residue analysis study found evidence for honeyed mead include among other fermented drinks on various Late Minoan and Late Helladic drinking cups (McGovern 2003:202-204). Because the same combination of items appears across multiple cups, the authors argue that the cups all contained the same mixed fermented beverage cocktail for ritual use (McGovern 2003:202—204).

§38. Lastly, in addition to honey, beeswax itself was an important commodity in the Bronze Age Aegean. In a study that conducted lipid analyses of absorbed residues on Cretan ceramic lamps during the LM I period, evidence of beeswax was found, suggesting that beeswax was used as lamp fuel in the Late Bronze Age (Evershed et al. 1997:984). Moreover, beeswax could have been used for lost-wax bronze casting, attested at its earliest in the Near East at around 3500 BCE (Kritsky 2015:6).

Beehive Types

§39. Looking at the archaeological evidence has also helped scholars identify different hive types from the Bronze Age. Three main hive types are potentially attested: the horizontal hive type, the vertical hive type, and skep beehives. The horizontal hive type is cylindrical, closed on one end and sealed off on the other with a removable lid that had a hole for the bees to travel through. The vertical type refers to a similarly lidded vessel that stood on its own, with the entry hole instead at the base of the vessel. Skeps are upturned woven baskets turned into beehives, and a well-attested practice in the Greek historical periods (Harissis 2018:25).

§40. Of these three types, only the vertical type has archaeological correlates in the Aegean (Harissis 2018:22—25). The other two types are argued to appear in the iconographic record; the horizontal hive type on iconographic scenes in seal rings, and skeps in the Flotilla Wall Painting at Akrotiri (Crowley 2014 and Papageorgiou 2016). If one looks beyond the Aegean, however, the horizontal hive type is also featured heavily in Egyptian wall-paintings in the Old, Middle, and New Kingdom periods, which indicates that the type certainly was used in the Eastern Mediterranean (Kritsky 2015:9—12, 20, 31—32).

The Organization of Apiculture

§41. Among the comparative evidence, the Egyptian material provides the most information regarding apiculture’s organization and administration. Based on accompanying religious titularies assigned to beekeepers, it seems that beekeeping was heavily associated with temples, and that the honey production was even tended to by temple beekeepers. The god Min had priests who were called ‘fty-priests, likely temple beekeepers, who would produce honey for specific ritual uses (Hammad 2018:2). Another type were the bjty-priests, who were in charge of gathering wild honey from desert regions under Min’s control (Hammad 2018:2).

§42. The Egyptian iconographic material also provides a recurrent vessel type that might have been used to store honey. At Saqqara in the pyramid of Unas, dated to the fifth dynasty (2450—2300 BCE), a beekeeping scene appears in a relief. In it, three spherical vessels with conical bases are depicted with the hieroglyphic inscription above it, translating as “a hekat of honey,” which denotes an Egyptian unit of volume equivalent to about 4.8 liters (Kritsky 2015:20). This vessel type is also represented at the solar temple of Newoserre at Shesepibre (2400s BCE), which has a beekeeping relief representing the different stages of honey production (Kritsky 2015:9, fig. 2.5). The vessel appears in the final stage of honey collection, called “the sealing of honey,” where it is shown getting stamped and wrapped closed.

The Tel Rehov Apiary and Scale

§43. Of final interest is an Iron Age apiary found within the ancient city of Tel Rehov, dated to around 897-891 BCE. It is the earliest and only surviving apiary that has survived into the archaeological record, with 30 beehives recovered of an estimated total 100 (Bloch et al. 2010:11240). Based on ethnographic studies, the hives likely yielded 3-5 kg of honey annually, meaning that around 300-500 kg of honey and 50-75 kg of beeswax could have been collected yearly from the apiary (Panitz-Cohen 2007:211). Given that 1.38 kg of honey is equivalent to 1 L of the commodity, this is equivalent to 217-362 L of honey. These metrics are essential for the next section, which quantifies the Linear B evidence for honey and investigates the identity of two occupational terms related to honey.

Part 2: The Linear B Evidence

Honey at Crete and Pylos

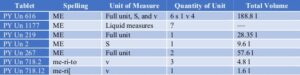

§44. The Linear B evidence for honey on Crete comes from Knossos and Khania and appears in varying textual and administrative contexts. At Knossos, the commodity appears in the Gg, Uc, U, and Fs series as the phonetic spelling “me-ri” (μέλι, or honey), the ideographic version “ME+RI,” or the genitive adjectival form “me-ri-te-o” or “honeyed.” Honey is typically quantified via the ideogram *209VAS at Knossos, which Bendall estimates to be 10.5-15.1 l, though the KN Fs series instead uses the Z liquid measurement and *211VAS ideogram (Bendall 2007:148—149). For Pylos, the evidence for honey, which is written instead as the logogram ME, is typically thought to be restricted to the PY Unseries, with also one instance of me-ri-ti-jo in PY Wr 1360. Further, only the “Major Unit” (MU) liquid measurement system is used. Within this system, one MU is equal to 28.8 l, one S unit 9.6 l, one v unit 1.6 l, and one z unit 0.4 l. While the other units have their own ideogram in the script, the 28.8 l MU does not. Instead, it is employed when ideogram and quantity alone is represented on a tablet, with no unique identifier of its own.

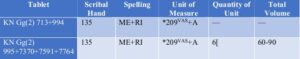

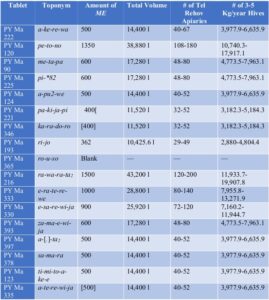

§45. In order to understand the scale of honey production at different sites, I quantified the tablets according to their equivalent volume in liters. For Knossos, these amounts are provided in the tables, which are divided according to set number and function per Bendall’s classifications (Bendall 2007:140—149):

Table 1. The Gg(1) set, offering records

Table 2. The Gg(2) set, perfumery records

Table 3. The Gg(3) set, more offering records

Table 4. The Gg(4) set, taxation records

Table 5. The Gg series, too fragmented to identify function

Table 6. The Fs series, function debated

Table 7. The KN Uc and U series

§46. Thus, in total, 969.2–1,449.2 l of honey are attested at Knossos. This means that 267.7–446.3 hives with yields of 3–5 kg/year, or 3–5 Tel Rehov apiaries, would have been required to produce honey in that amount. And given that the quantities listed on the Knossos tablets are mostly concerned with individual religious dedications, it is very likely that this is just a snapshot of a larger annual honey output.

§47. I also quantified the Pylos tablets, though things were more complicated here because of the PY Ma series. These are a series of tax assessment tablets that track whether certain agricultural products taxed from different regions of Pylos were actually paid in full (Shelmerdine 1973:261). In the series, the same six items, labelled as commodities A-F, are taxed, and all the tablets follow the same general proportion of 7A : 7B : 2C: 3D : 1.5E : 150F, albeit with some slight deviation (Shelmerdine 1973:263). This seems to indicate that the palace taxed different districts across Pylos according to the same general standard unit (Shelmerdine 1973:263).

§48. Despite commodity F being the ideogram *13 ME, which could be an abbreviation for honey, the general consensus is that the quantities that it is listed with are too big for it to represent honey. Numbers reach as high as 1500 ME (Docs2 53, Shelmerdine 1973:262, Bendall 2007:150). However, that honey is represented in the Ma series, I argue, should not be out of the question. While the standard MU full liquid amount is 28.8 liters, whether this should apply to honey here should not be assumed outright. The scribe is quantifying the honey without giving units. Does this mean that he is conforming to the liquid measurement system, or did he simply think it unnecessary to provide units? I.e., since he is using the tablets for his own system-internal reference, does he need to write out a specific vessel or measurement if he and other scribes know it, or can he simply record the number of an assumed unit? Moreover, given that these tablets are listing total amounts of different commodities in different districts surrounding Pylos, even if they are ‘large,’ without understanding how extensive honey production was in the region, the feasibility of such quantities cannot be determined outright.

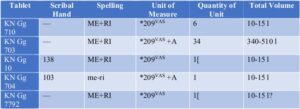

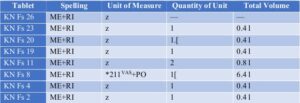

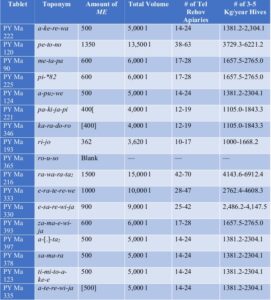

§49. If one excludes the PY Ma series when looking at the Pylos tablets, then around 291.2 liters of honey would be attested, as seen below:

Table 8. The PY Un tablets, feasting, perfumery, religious offerings

![]()

Table 9. The PY Wr tablet, wine ingredient

§50. This is equivalent to 80.4—134.2 3—5 kg/year hives, or 1—2 Tel-Rehov sized apiaries. However, if one does consider the Ma tablets, with the MU Liquid measurements used as is normally done, things look as they do in the table below:

Table 10. Hive and apiary estimations for the Ma series, full 28.8 liters liquid measure

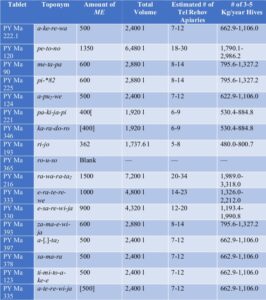

§51. Since the scribe might be using his own scribe-internal system and not recording units, what might also be helpful is if we broke the amounts down using two different units of measure—a 10 liter (~9.6 liter Linear B S liquid-measurement unit) amphora and a 4.8 L hekat of honey—as stand-ins for smaller vessels:

Table 11. Hive and apiary estimations for the Ma series, 10 liters amphora

Table 12. Hive and apiary estimations for the Ma series, 4.8 liters hekat of Honey

§52. Providing the totals for these three tables, if the MU 28.8 L unit is used in the Ma series, then 857 to 1,360 Tel Rehov-sized apiaries would need to exist to meet the capacity demand, or 85,222.5 to 142,168.5 3—5 kg/year hives. If the 10 L amphora measure is used, the total honey output for all of Pylos would equal 107,120 L per annum, requiring 29,591.2—49,364.1 3—5 kg/year hives. Finally, if the 4.8 L hekat measure is used, there would be a total per annum output of 51,417.6 L of honey, requiring 14,203.8—23,694.7 3—5 kg/year hives.

§53. If we knew the geographical extent of these regions, population size, etc., it might then be possible to reason out the plausibility of these numbers, but we do not. What we do have, however, is additional ethnographical data from Egypt. Eva Crane, an ancient beekeeping expert, reports in her book The World History of Beekeeping and Honeyhunting that when driving down a 70 km stretch of road in 1978, she counted horizontal hives stacked beside the Nile in numbers of 2,400, 2,600, 600, 4,200, 4,600, and 400, totaling to 14,800 hives (Crane 1999:168). Hive lengths she measured were only slightly longer than those found at Tel Rehov, 15 cm wide by 120 cm long (or around 6 inches wide 47 inches long) (Crane 1999:167). If horizontal hive apiaries in similar sizes existed in mainland Greece, it seems possible that the numbers in the Ma series could have been sustained district by district.

§54. At the same time, one does need to be careful. Egypt’s environmental setting is different from Greece’s, and modern numbers might be what they are because of a higher population, thus more people keeping bees. But given these ethnographic parallels, that ME is written as honey elsewhere in the Pylos tablets, and the potential that the scribe could be using his own system-internal reference to record the honey, perhaps the numbers listed in the Ma tablets are not as outlandish as initially thought. At the very least, their interpretation as honey should not be immediately dismissed.

Occupational Terms at Pylos

§55. Concerning job titles related to honey, there are two extant. First is me-ri-du/da-me-te, which appears almost exclusively at Pylos, with the exception of a fragmented KN X tablet that yields little information. At Pylos, the term appears in the An and Fn series, which both deal with individuals and groups who are designated by their occupation or position. The An series seems to record the number of people of a given profession according to the region they are from (PTT I 57). The Fn series deals with allotments of the HORD and GRA commodity (PTT I 153). Many of the recipients are groups of workers, and in the cases where μελιδάμαρτεϛ appears, grain is given directly to the work groups themselves. Combining these details with the linguistics of the term da-mo, which Roger Woodard connects to the cultic alongside the po-ro-du-ma-te ‘feather/wing-dumartes,” it seems that μελιδὰμαρτεϛ is a collective title of religious functionaries who did something related to honey (Woodard 2021:§121-124). What these officials did specifically, however, is not entirely clear.

§56. The second term is me-ri-te-wo, which represents the genitive singular μελιτῆϝοϛ, making the nominative form μελιτεύς (Aura Jorro 1985:440). The term appears exclusively in the PY Ea land tenure tablets. According to Nakassis, the individual named ku-ro-no in PY Ea 813 is the sole me-ri-te-u listed within the series, where he both possesses a sizeable lease of land and subleases four parcels to other people, including e-u-me-de the a-re-pa-zo-o, or “unguent boiler” (Nakassis 2013:302). Given this and Nikoloudis’ suggestion that the Ea series documents a tanning operation (Nikoloudis 2010:287—298), it could then be posited that the me-ri-te-u is perhaps someone who was involved with the collection of honey and its products for this entire area, and who relied on beekeepers to produce honey itself.

§57. When looking at these occupational terms and comparing them with the Eastern Mediterranean materials in the first section, we get a glimpse at how apiculture might have been organized. The “honeyman” who seems responsible for the collection and production of honey brings to mind the hierarchical structure of apiculture in Egypt. Further, the inclusion of the μελιδάμαρτες, which seems to possess a cultic connotation, reminds one of the temple beekeepers or wild honey-hunting priests. Combining the presence of these terms alongside the numbers we tabulated, it seems likely that honey was an important commodity that the palace had direct involvement with. Further, the presence of an administrative official for beekeeping suggests organization and bureaucracy, which is essential for our discussion of scale.

§58. These two chapters have done much to help answer questions concerning honey’s production and its potential involvement with religion. Less attention, however, has been given to the actual religious significance of honey in the Aegean Bronze Age. In order to understand this, a discussion of the significance of bees and honey in Later Greece follows.

Part 3: Later Greek Literary Record: Homerica and Religious References for Bees and Honey

§59. This final section presents the last stream of evidence for bees, honey, and apiculture discussed in my thesis: the Homeric and later Greek literary sources. Here, I looked at the religious and cultic significance of bees and honey’s appearance in Homer and later Greek Literature. This will help us understand the potential identity of the melidamartesas described by Woodard, whether honey production could have been ‘controlled’ by a religious group, and what that control might have looked like.

Religious symbolism of bees and in myth and ritual

§60. Bees possessed cultic and mythical significance in Greek Religion, featuring in numerous rituals and stories. Priestesses were often called bees in mystery cults. For instance, the devotees of Demeter Thesmophorus were called μέλισσαι, or “bees” (Detienne 1989:145). Similarly, in Aeschylus Fragment 87, found in the scholia of Aristophanes’ Frogs, the priestesses of Artemis are called μελισσονόμοι, the substantive version of an adjective that means “bee-keeping” (Aeschylus Fr. 87). Finally, in Pindar’s Pythia 4, the poet calls the Oracle the μελίσσας Δελφίδος or “Delphic Bee.”

§61. The title ‘μελίσσας Δελφίδος’ indicates how bees are often connected to prophecy and oracles. This is displayed as early as the Homeric Hymn to Hermes, where bees are described as having oracular capabilities. Near the end of the hymn, when Apollo and Hermes are exchanging gifts, Apollo gives his new friend “three virgins lifted on swift wings” who “teach their own kind of fortune telling…They like to tell the truth when they have eaten honey and the spirit is on them; but if they’ve been deprived of that divine sweetness, they buzz about and mumble lies” (Hymn to Hermes 59-60, transl. from Hyde 1998:317-331).

§62. Because they inhabit the Parnassus, scholars have linked these “bee maidens” with the Thriae, three virgin sisters with hybrid bee-human bodies who inhabited the sacred springs of the Corycian Cave in Phocis (Larson 1996:350). Larson suggests that a cave discovered in the same region, with religious activity dating back to the 7thcentury BCE, may in fact be a site where the Thriae were worshiped, which is fascinating because of the discovery of astragali at the site, which typically feature in fortune-telling rituals (Larson 1996:350). Using the behavior of the bee maidens in the hymn, which seems reminiscent of omen watching, she then suggests that the cave might have had an oracle, who used bees in divination rituals (Larson 1996:355-356). Since honey was often a dedicatory offering to nymphs, Larson posits that perhaps a libation was poured in the cave, causing bees to swarm around the honey, and their movements and/or sounds then might have been read and interpreted alongside the casting of lots (Larson 1996:355-356).

Honey in Homer and Myth: Funerary contexts and Bronze Age continuities

§63. In addition to bees, honey also features in both the Iliad and Odyssey, namely in funerary contexts. In the funeral of Patroclus in Il. 23.170, Achilles is seen setting amphorae of honey and oil against the bier alongside horses, bronze vessels, and other items. Moreover, in the Od. 24.68, when describing the funeral of Achilles, Agamemnon says that the dead hero’s body was burned with anointing oil and lots of honey. This leads to another symbolic value that honey possessed: its association with death. Later Greece keeps this association as well, and it is thought that part of this has to do with the cavernous settings that bees were associated with. Because caves were often considered as gateways to the underworld, bees had similar deathly associations (Tyree et al. 2012:330).

§64. Honey is also featured in the myth about the death of Glaucus, son of King Minos and Queen Pasiphaë (Tyree et al. 2012). After playing with a mouse, the young Glaucus goes missing (Tyree et al. 2012:330). When searching for him, Polyidus sees an owl driving away bees from the wine-cellar, and there he finds the boy submerged in a cask of honey, dead (Tyree et al. 2012:330).

Conclusions: What We Can and Cannot Say About Apiculture in the Aegean Bronze Age

§65. Looking at the various archaeological, iconographic, and literary sources for apiculture, honey, and bees in the Mediterranean world has proved an effective means for understanding apiculture’s scale and the degree of religious control over the industry in the Aegean Bronze Age. Examining the Eastern Mediterranean comparative material has helped elucidate the uses that could have incentivized honey and beeswax production and given ideas for how apiculture might have been organized in the Aegean. Further, quantifying honey in the Linear B corpus and comparing the numbers to ethnographic parallels has shown that the amounts listed in the PY Ma tablets, if ME stands for ‘honey’, originally found improbable, now have more backing.

§66. The comparanda and later Greek materials have also helped with clarifying the roles of the two occupational terms related to honey. The meliteus is likely a person in charge of the collection of honey for a given region. Further, the melidu/damartes seems to have been group of religious functionaries who dealt with honey in some way. While the precise identity of these functionaries and their responsibilities remains unclear, the female cultic officials of later Greece, the Egyptian beekeeper priests, and the potential oracular associations with bees evidenced in later Greek religion present a variety of options. Given that bees and honey had connections to death, the oracular, and devotion to the gods, as well as associations with Nymphs in historic Greece, the possibilities grow even further. At the very least, we can say that it is not surprising that the Mycenaeans had a cultic official who dealt with honey.

§67. More work can still be done. To truly get a sense of the scale and organization of apiculture in Bronze Age Greece, we need to compare our numbers to those attested in historic periods, as well as with other Bronze Age industries. We also need to define what ‘large-scale’ really means. Does it refer to the amount of human labor devoted to a given task in a society? Does it refer to the amounts of a commodity produced per annum? A sum of these two? Or does it refer to a singular type or methodology of honey production, such as formal apiculture? Finally, more study needs to be done on the environmental capacity of Pylos, and whether the numbers in the Ma tablets exceed or fit this capacity.

§68. Even so, we now have the groundwork necessary to do these sorts of things and answer these sorts of questions. We now know more about the industry than we did before: how honey was produced, how much was produced, and what people were involved in its production. By studying and quantifying apiculture in later periods, we might be able to understand not only more about the scale apiculture in the Bronze Age, but also establish a methodology for examining scale in other industries. This, in turn, will give us a window into the lives of the Mycenaean Greeks, their relationship to the palatial system, and to each other.

Petroll’s Bibliography

Aura Jorro, F. 1985. Diccionario micénico. Diccionario Griego-Español Anejo 1. Madrid.

Bendall, L. M. 2007. Economics of Religion in the Mycenaean World: Resources Dedicated to Religion in the Mycenaean Palace Economy. Oxford.

Bloch, G., T. M. Francoy, I. Wachtel, N. Panitz-Cohen, S. Fuchs, and A. Mazar. 2010. “Industrial apiculture in the Jordan Valley during biblical times with Anatolian honeybees.” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 107:11240–11244.

Crane, E. 1999. The World History of Beekeeping and Honeyhunting. New York.

Crowley, J. 2014. “Beehives and Bees in Gold Signet Ring Designs.” In KE-RA-ME-JA: Studies Presented to Cynthia Shelmerdine, eds. D. Nakassis, J. Gulizio, and S. A. James, 129–139. Philadelphia.

Detienne, M. 1989. “The Violence of Wellborn Ladies: Women in the Thesmophoria.” In The Cuisine of Sacrifice among the Greeks, eds. M. Detienne and J. P. Vernant, 129–147. Chicago.

Docs2 = Ventris, M. and J. Chadwick. 1973. Documents in Mycenaean Greek. 2nd ed. Cambridge.

Evershed, R. P., S. J. Vaughn, S. N. Dudd, and J. S. Soles. 1997. “Fuel for thought? Beeswax in lamps and conical cups from Late Minoan Crete.” Antiquity 71:979–985.

Hammad, M. B. 2018. “Bees and Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt.” Journal of Association of Arab Universities for Tourism and Hospitality 15:1–16.

Harissis, H. V. 2017. “Beekeeping in Prehistoric Greece.” In Beekeeping in the Mediterranean from Antiquity to the Present, eds. F. Hatjina, G. Mavrofridis, and R. Jones, 18–39. Nea Moudania.

Hyde, L. 1998. Trickster makes this world. New York.

Karnava, A. and I. Nikolakopoulou. 2005. “A pithos fragment with a Linear A inscription from Akrotiri, Thera.” Studi micenei ed egeo-anatolici 47:213—225.

Kritsky, G. 2015. Tears of Re: Beekeeping in Ancient Egypt. Oxford.

Larson, J. 1995. “The Corycian Nymphs and the Bee Maidens of the Homeric Hymn to Hermes.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 36:341–357.

McGovern, P. E. 2007. “The Chemical Identification of Resinated Wine and a Mixed Fermented Beverage in Bronze Age Pottery Vessels of Greece.” In Archaeology Meets Science: Biomolecular Investigations in Bronze Age Greece: The Primary Scientific Evidence, 1997-2003, eds. Y. Tzedakis, H. Martlew, and M. K. Jones, 169–218. Oxford.

Nakassis, D. 2013. Individuals and Society in Mycenaean Pylos. Leiden and Boston.

Nikoloudis, S. 2012. “Thoughts on a Possible Link between the PY Ea Series and a Mycenaean Tanning Operation.” In Études mycéniennes 2010. Actes du XIIIe colloque international sur les textes égéens, Sèvres, Paris, Nanterre, 20-23 septembre 2010, eds. P. Carlier, C. De Lamberterie, M. Egetmeyer, N. Guilleux, F. Rougemount, and J. Zurback, 285–301. Pisa and Rome.

Panitz-Cohen, N. 2007. “It is the land of honey: Beekeeping at Tel Rehov.” Near Eastern Archaeology 70:203–219.

Papageorgiou, I. 2016. “Truth Lies in the Details: Identifying an Apiary in the Miniature Wall Painting from Akrotiri, Thera.” In The Annual of the British School at Athens 111:95–120.

PTT I = Bennett, E. L., and J.-P. Olivier. 1973. The Pylos Tablets Transcribed. vol. 1. Rome.

Shelmerdine, C. W. 1973. “The Pylos Ma Tablets Reconsidered.” American Journal of Archaeology 77:261–275.

Tyree, L., H. L. Robinson, and P. Stamataki. 2012. “Minoan Bee Smokers: An Experimental Approach.” In PHILISTOR: Studies in Honor of Costis Davaras, eds. E. Mantzourani and P. P. Betancourt, 222–232. Philadelphia.

Vlazaki, M. 2010. “‘Iris cretica’ and the Prepalatial Workshop of Chamalevri.” In British School at Athens Studies18:359–366.

Woodard, R. D. 2021. “Linear B du-ma/da-ma, Luvo-Hittite Dammara-, and Mycenaean Dialects.” In Pierini, R. and T. G. Palaima. 2021. “MASt@CHS – Summer Seminar 2021 (Friday, July 23): Summaries of Presentations and Discussion.” Classical Inquiries.

Topic 3: Examining the Crossroads of the Chi: The Lozenge as a Multivalent Representation of Christ and Opportunity for Spiritual Meditation in Early Medieval Insular Manuscripts

Presenter: Jennifer Lowell (jenniferhlowell@gmail.com)

§69. The lozenge, defined here as the rhombus shape inclusive of subtle variations to this geometric form, comprises a uniquely multivalent symbol in the context of Insular manuscript illuminations. The illuminations and textual arrangements presented herein demonstrate that the lozenge is capable of multiple and flexible meanings, representing Christ as the Logos incarnate; hearkening to the complex nature of sacred text and the practice of engaging with them in the medieval era; and alluding to the Gospel of St John and Christ in majesty as well as broader associations with Christ as the manifestation of God’s creations and divine word.

§70. Insular works in the early medieval period are especially recognized as imbuing decoration of sacred texts with meaning. As Richardson explains, such adornment serves “as an aid to spiritual contemplation” (Richardson 1984:46), offering a venue for meditation upon sacred texts for readers, or simply those with visual access to manuscripts, who would commonly regard the process of beholding these texts as an act of faith. Indeed, Richardson suggests that it is “no wonder that early Irish writers were so fond of the expression ‘to see with the eyes of the mind’ or ‘the eyes of the heart’” (Richardson 1984:46), underscoring Insular scribes’ and readers’ awareness and intentional promotion of the relationship between sacred text and spiritual connection.

§71. The intricate composition of the so-called Chi Rho page, folio 34v in the Book of Kells (the Book of Kells. C. 800. Iona. Dublin: Trinity College Library, MS 58), provides one of the most exemplary illuminations in which the lozenge conveys its multivalent meanings and guides visually through and spiritually into the text at hand. This folio’s status as a masterpiece of medieval artwork and artistic genius is largely due to the purposeful and fascinating interweaving of abstract and figural ornamentations associated with Christian values and texts, of which the lozenges play an integral part.

§72. Lozenges are prominently displayed in this folio’s focal Chi shape as well as a myriad of ornamental designs. Forming the crux of the abstracted Chi shape that grounds the composition of this folio, lozenges draw one’s eye to the center of this intricate page and a bright white lozenge at very center of the sweeping Chi. Alongside the fancifully abstracted letter Rho, the lozenge reminds viewers that Christ is imbued in the sacred words contained in this text. It is also interesting to note that the moths drawn at the upper left-hand curve of the Chi seem to be nibbling on a small lozenge, perhaps sacramental bread, further alluding to Christ as the Logos incarnate.

§73. Tracing the transformation of the universal shape of the lozenge into a symbol with distinctly Christian meaning arguably requires more of a global and anthropological perspective than is feasible for a study of this length. For example, a wealth of textile fragments from late antiquity ascribed to Coptic and broader Egyptian communities employ the lozenge shape as both a decorative and spiritually salient motif; the Cleveland Museum of Art’s textile collections include sixth-century ornamental bands that demonstrate the use of the lozenge shape as a metonym for Christ and indication of divine splendor particularly well. Thus, while many cultures and media present the lozenge as a salient motif, this paper explores the opportunities for multivalence that the material and literary contexts of manuscripts offer.

§74. The Chi shape as a metonym for Christ and geometric ground of compositions is especially well suited for symbolic development in manuscript illuminations and text. Folios 30v and 31r in the Book of Kells clearly demonstrate the lozenge’s role as a metonym for Christ. Each of these facing folios bears a central lozenge adorned with golden yellow and regal purple pigments. Visually, each lozenge sits at the center of the folio and at the center of partially illuminated crosses dividing the written passages therein.

§75. The lozenge on folio 31r further illustrates the concept of Christ as Logos and the spiritual ground of the world, according to medieval Christian consciousness, by serving both as a focal symbol and as the letter O commencing the word Omnes in a passage describing the divine genesis of the world. As Tilghman notes, the purple and golden yellow colors used in these lozenges and in the name of Christ on folio 31r enhances the visual connections made between Christ, the lozenges, and Logos (Tilghman 2011:292). The lozenge thus connects the sacred text at hand to all that the Bible describes as being created by God.

§76. Folio 6r in the Codex Amiatinus, created circa 716 CE in Northumbria (Wearmouth-Jarrow, Northumbria. Florence: Biblioteca Medicea Laurenziana), reinforces this multivalent symbolism, offering an interpretation of equivalence between the cross shape and lozenge. As Darby explains, this composition enumerates book volumes and testamenta (Darby 2017:350) and presumably lays out elements of the Gospel of Luke, as indicated by the figure of the bull vividly colored at the top of the page. The alternating lozenge and cross shapes containing the testamenta provide another example of the lozenge as a metonym for the cross and Christ.

§77. The lozenges depicted in folios 2v and 3r in the Codex Amiatinus adorn the veil at the Tabernacle, presenting another instance of the lozenge as metonymic for Christ while serving as an element of decorative splendor. Although depictions of the veil at the Tabernacle vary, Tilghman notes that most portray the veil with lozenges, or “diaper pattern and fleurs de lis” as established in Late Roman Christian iconography (Tilghman 2017:171). That the Tabernacle veil, widely considered to be a representation of Christ’s body, is more or less consistently depicted with lozenges demonstrates the dual decorative importance and religious salience of this shape as analogous to Christ. Connections between the lozenge symbol used in textiles in late antiquity and in distinctly Christian settings present an intriguing point of further study.

§78. Folio 5r in the Codex Amiatinus further evidences the lozenge as multivalent symbol alluding to Christ as the Logos incarnate. The book covers depicted in this illumination are structured by lozenges, reflecting both a design and a recognizable composition associated with Christ. Though difficult to make out, the two lozenges appear to frame crosses or at least an equilateral geometric shape alluded to by these dots. Additionally, the white decorative shapes at the bottom of the bookcase appear to represent a cross and possible peacock, both well-known symbols of Christ, and thus underscore the interpretation of the decorative lozenges as representing Christ. Once again, readers of this text are reminded of Christ as the Logos incarnate as they embark on the spiritual practice of engaging with these sacred texts.

§79. The so-called Quoniam page on folio 188r in the Book of Kells further demonstrates the versatility of the lozenge, especially in the theological context of the apocalypse and material context of manuscripts. The first three letters of the incipit present the lozenge as a subtle, yet essential focal point rendered as central figure in this geometric composition. The letters Q, U, and O, presented as a Greek Omega,[2] are highly abstracted and appear to form an ornate book cover. More specifically, the rectangular Q frames a smaller rectangle, richly bordered with red, purple, and golden yellow pigments and designs, that contains a central lozenge, which in turn frames the U and O/Omega.

§80. The arrangement of the lozenge both framing and framed by these shapes looks just like medieval book cover designs, as seen in folio 5r in the Codex Amiantinus, and hearkens to the spiritual practice of engaging with these texts. This symbolism is further augmented by the fact that this illumination commences the Gospel of Luke, thus serving as a book cover itself. Tilghman points to the letters U and O, as a “visual puzzle” (Tilghman 2011:297) recalling Christ as the Alpha and Omega, or divine Logos grounding the universe; visually connecting the U and O would create a Chi cross shape framed by the central lozenge within the letter Q and thereby complete this symbolic and spiritual puzzle.

§81. The figural depictions surrounding the remaining letters of the word Quoniam also allude to these complex theological concepts as well as the Christian apocalypse, or rapture, wherein the earthly world ends and believers are transformed to join Christ and God in eternity. The lozenge thus serves many symbolic purposes, such as outlining a book cover, and apocalypse, and framing the Chi cross/Alpha and Omega puzzle hearkening to Christ as the Logos incarnate.

§82. Folio 796v in the Codex Amiantinus presents lozenges as a depiction of gemstones[3] adorning the representational figure of Christ, who sits enthroned in all his divine glory with the four evangelists and their symbols surrounding him, i.e. in the Maiestas Domini pose, associated with the apocalypse. Darby points out that the book held by Christ forms the center of the folio as well as the point of intersection created by tracing lines between the books held by the evangelists in this illumination, thus displaying “a new creation formed by the harmonious meeting of its constituent parts” (Darby 2017:364).