Integrating Perspectives: New Insights into Mycenaean Research Strategies and Western Anatolia. Papers and Summary of the Discussion held at the Fall 2024 MASt Seminar (Friday, October 4)

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Fall 2024 session of the MASt seminars by welcoming the participants to the October meeting and sharing some great news about MASt’s members’ recent achievements.

§2. MASt secretary Giulia Muti has been awarded the Council for British Research in Levant (CBRL) 2024 Levant Summer Prize for Early Career Best Paper for her paper “Discoid loom weights on Cyprus: new insights into textile tools and practical knowledge from the Aegean”. Massive congratulations, dear Giulia!

§3. The Fall 2024 MASt seminar featured Tom Palaima and Livio Warbinek as speakers.

§4. Tom Palaima presented “First Principles and Research Strategies in Mycenology. New Old Problems: PY Vn 130 and PY Un 267; o-ze-to and ze-so-me-no; the use and meaning of pa-ro in sealings and feasting/sacrifice and landholding texts”.

§5. Palaima’s paper focused on the relationship between the Pylos tablets PY Vn 130 and PY Un 267 and the implications that their connection, or the lack thereof, have on the interpretation of both texts and their broader context.

§6. As such, Palaima read both tablets within the context of the perfumed oil from Late Bronze Age Pylos as attested to in the Linear B tablets. As such, his paper expanded on his 2014 paper “Pylos Tablet Vn 130 and the Pylos Perfume Industry”, thus adding new thoughts on the old problems of the PY Vn 130 and Un 267 connection, as well as the interpretation of the Mycenaean words o-ze-to, ze-so-me-no, and pa-ro.

§7. Livio Warbinek gave a presentation titled “Hittites and Ahhiyawa in Western Anatolia: Two Worlds face-to-face”, offering an overview of the relationship between the Aegean and the Anatolian societies during the Late Bronze Age and addressing the hotly debated matter of the “Ahhiyawa Question”.

§8. By doing so, Warbinek showed how problematic the relationship between the Ahhiyawa and Hittite people was. In addition, he collected the available sources to compare the two cultures.

§9. Warbinek’s conclusions addressed how difficult the dialogue between the two parties was due to their different sense of self and others’ perceptions. In his view, such a challenge explains why mutual relations face-to-face have never been consolidated as in other circumstances or contexts of the Ancient Near East.

§10. In addition to the MASt board members (Editor-in-Chief: Rachele Pierini; Associate Editor: Tom Palaima; Editorial committee members: Elena Džukeska, Joseph Maran, Leonard Muellner, Gregory Nagy, Marie Louise Nosch, Thomas Olander, Birgit Olsen, Helena Tomas, Agata Ulanowska, Roger Woodard; Secretary: Giulia Muti; Editorial Assistants: Harriet Cliffen, Linda Rocchi, Katarzyna Żebrowska; Student Assistant: Matilda Agdler), roughly 90 attendees took part in the Fall 2024 MASt seminar, among whom Clara Candisano, Stephen Colvin, Janice Crowley, Sophie Cushman, Paola Dardano, Lavinia Giorgi, José Miguel Jiménez Delgado, Bernice Jones, Robert Koehl, Daniel Kölligan, Maria Kostoula, Hedvig Landenius Enegren, Daniela Lefèvre-Novaro, Olga Levaniouk, Christian Lindesay, Jesse Lundquist, Nicoletta Momigliano, Sarah Morris, Konrad Mueller, Leonard Muellner, Alexandra Patrianakou, Jeremy Rau, Matthew Scarborough, Kim Shelton.

§11. Substantial discussions followed both presentations. Specifically, contributions to the seminar were made by Janice Crowley (see below at §§164; 166), Elena Džukeska (§113), José Miguel Jiménez Delgado (§§106; 108; 111; 117), Robert Koehl (§§168; 170; 172), Sarah Morris (§§139—142; 154), Greg Nagy (§§155; 158—162), Tom Palaima (§§107; 109—110; 112; 114—116; 118; 121—126; 128—129; 147; 150; 156; 171), Rachele Pierini (§§120; 127), Matthew Scarborough (§157), Livio Warbinek (§§143—146; 148—149; 152—153; 163, 165; 167; 169), Roger Woodard (§§105; 119; 151; 173).

First Principles and Research Strategies in Mycenology. New Old Problems: PY Vn 130 and PY Un 267; o-ze-to and ze-so-me-no; The Use and Meaning of pa-ro in Sealings and Feasting/Sacrifice and Landholding Texts

Presenter: Tom Palaima

§12. In 1987 I published a long paper delivered at the five-year CIPEM conference in Ohrid, then Yugoslavia, on the texts of Mycenaean inscribed sealings as they relate to the texts of Linear B tablets (Palaima 1987). In their ground-breaking study of how sealings (also known as inscribed nodules) work administratively, Olivier, Melena and Piteros 1990 cite Palaima 1987 and say this about the interpretative framework in which their own ideas developed:

Le traitement d’ensemble le plus complet de ce genre de document est dû à Th. G. Palaima, lequel a eu parfaitement raison d’écrire :

The focus in Mycenology has so far been very specialized, concentrating on inscribed sealings and especially on those individual sealings or coherent groups of sealings whose brief inscriptions: (1) relate directly to the contents of tablets found in exactly or approximately the same archaeological context; (2) relate to the functions of the areas where they were discovered, as determined by artefacts, architecture, and the overall archaeological record; (3) contain lexical items pertinent to a more general discussions

et d’en tirer la conclusion, une page plus loin, que si l’on voulait comprendre quelque chose aux «sealings», inscrits et non inscrits, il fallait les prendre en considération dans l’ensemble des systèmes économiques à Knossos, Pylos et Mycènes.

Vaste programme, dont l’auteur a d’ailleurs fort bien tracé les cadres et commence à exploiter la matière. Nous verrons in fine comment les nouveaux documents de Thèbes confortent certains de ses résultats. Mais signalons dès à present, afin que les choses soient parfaitement claires, que nous sommes entièrement d’accord avec son ultime conclusion, laquelle est de type négatif : “no sealings need have been used to label collections of tablets or storage boxes.”

§13. In the course of studies of Linear B tablet and sealing administration during the 37 years since Palaima 1987, I have looked at particular problems, often with epistemological ramifications.[1]

§14. A decade ago, I published an article (Palaima 2014a) in the Cynthia Shelmerdine Festschrift with the title “Pylos Tablet Vn 130 and the Pylos Perfume Oil Industry.” I dealt with the puzzling, and therefore largely neglected, tablet Vn 130 and addressed five main problems relating to its interpretation. My starting point was the definite and unique pairing of Pylos tablet Vn 130 in size, shape, textual format and, I argued, a key shared term with Pylos tablet Un 267, a much-cited text having to do with the major industry of manufacturing perfumed olive oil.[2]

§15. A recent article by John Killen (Killen 2023) rejects the pairing of Vn 130 and Un 267 and interprets them using Killen’s distinctive intertextual method. I therefore have re-examined the Vn 130/Un 267 connection and rethought my own arguments on five main points, which I discuss here.

§16. The five problems are:[3]

- The relationship of Vn 130 and Un 267, two tablets by Hand 1, the ‘master scribe at Pylos’.

Figures 1 and 2. Vn 130 and Un 267 compared side by side. Rectos (Figure 1). Versos (Figure 2).

CREDIT: Photo of Vn 130 and Un 267 rectos courtesy of The Pylos Tablets Digital Project

Palace of Nestor Excavations, the Department of Classics, University of Cincinnati. Photo by Dimitri Nakassis. Image editing by John Klausmeyer. Katerina Voutsa and Kostas Nikolentzos of the National Archeological Museum in Athens for facilitating their work made photographing possible.

- On sealings and on tablets relating to livestock and landholdings, the specific meaning (or semantics and historical development) of the preverb/preposition pa-ro.

- The interpretation of the heading phrase on Pylos tablet Vn 130 and its initial word-unit o-ze-to in the context of other such tablets with text-heading phrases beginning in o- or jo-.

- The role of qa-si-re-we (singular qa-si-re-u) in Mycenaean regional economic systems and how ‘specialized’ within one ‘sphere’ of the economy individuals clearly documented as working in a sphere like bronze-working are likely to have been in the annual administrative period when the Palace of Nestor at Pylos in Messenia was destroyed.

- More generally, understanding the contents of the Linear B documents and their implications for what kinds of economic activities can be going on during the days, weeks, or months when the Linear B documents that have survived were written and stored relevant to human activities in the palatial territory in late Bronze Age Messenia during the last days of the Pylos polity (Palaima 1995; Davis et al. 2024).

§17. All five points are important for reconstructing the social, economic, religious, and political activities taking place, in this case in the region of Messenia, in the period preceding the LH III C:1 (ca. 1170 BCE) destruction (Davis et al. 2024) of the Palace of Nestor.

§18. Tablet Vn 130 has long been open to discussion (but it has also been avoided by major handbooks including Killen 2024)[4] chiefly for three reasons.

§19. Reason 1: the identification and meaning of the main verb (-ze-to) in the formulaic header of Vn 130 were uncertain; its stem is spelled in Linear B as ze- and, given how the form is represented on Vn 130, the verb in question would seem to be athematic. Most solutions, therefore, including my own in 2014 following J.L. Melena 2014, have argued in favor of an athematic form. I now here have a different and more cogent proposal, but connected with the same verbal root, so that my overall argument remains generally intact.

§20. Reason 2: on tablet Vn 130, Hand 1 records, in whole numbers, items that have no ideograms, but most likely are identified in line 2 of the text by the rubric word a-ke-a2. It is generally accepted now that a-ke-a2 are aggeha = ἄγγεα, but what kind of ‘receptacles’ these are and for what purpose(s) they are being recorded is open to question in part because the main verb has long been unidentified.

§21. According to Chantraine 2009 s.v. and Beekes 2020 s.v., ἄγγεα are containers or vessels with no specification of shape or material. A gloss cited by Beekes gives ἄγδυς· ἄγγος Κρήτικον. This gloss suggests a tempting connection with what we conventionally call ‘Minoan’ or substrate terminology (cf., e.g., words in -inthos or -ssos like asaminthos, Tylissos, Knossos) for objects and items used originally in the early culture(s) of Minoan Crete and the later Greek mainland.

§22. Leonard Palmer (1963:370) did take up commenting on Vn 130. Palmer noted that the position of a-ke-a2 in line 2 of Vn 130 is “ambiguous” and proposed, N.B., that a-ke-a2 is probably not part of the introductory phrase on line 1 (italics mine for emphasis). Palmer proposed that the word-unit a-ke-a2 was ἄγχεα ‘mountain hollows’ specifying some ‘outlying place’ in the district of me-ta-pa, the place name registered in the first entry (also on line 2).

§23. Palmer’s reading of a-ke-a2 is no longer followed, but his observation about the anomalous and therefore ambiguous positioning of a-ke-a2 still stands. a-ke-a2 functions as a rubric specifying the objects listed in lines 2–13. It also takes up space on line 2 that makes the first of the twelve entries on the tablet irregular. This is important because the argument is made that the ἄγγεα are the accusative object of the heading verb -ze-to. It can be argued, however, that it is not part of the syntax of the opening phrase. In that case ze-to, as a causative middle, would have no expressed direct object.[5]

§24. Palmer also noted that there are ‘two hints’—thus making clear the tentative nature of such associations—in the twelve entries in Vn 130 about what the tablet is recording. We should note that by his peculiar ‘reading’ of a-ke-a2, Palmer eliminated the main clue as to what items were being enumerated on the tablet. Therefore, when one of the twelve entries on the tablet had a parallel in a text related to bronze-working and another to the ‘owner’ or ‘leader’ of a group of men known as a qa-si-re-wi-ja, he was unconstrained in suggesting that those two parallels held the key to interpreting the entire text on Vn 130.

§25. For convenience I give here at the start the texts of the two tablets we will be examining, PY Vn 130 and PY Un 267. The texts are taken from the forthcoming corpus edition of the tablets from Pylos, Palace of Nestor IV,1 now finally, as I write, in final (3rd) proofs.

Vn 130 (8, H1)

1 o-ze-to , ke-sa-do-ro , *34-to-pi ,

.a pa-ro

2 a-ke-a2 , me-ta-pa , pe-ri-te 1

3 a-pi-no-e-wi-jo , pa-ro , e-ru-si-jo 1

4 a-pi-no-e-wi-jo , pa-ro , a3-ki-e-we 4

5 e-na-po-ro , pa-ro , wa-do-me-no 9

6 sa-ri-no-te , pa-ro , o-wo-to 5

7 pa-ki-ja-si , pa-ro , a-ta-no-re 4

8 ka-ra-do-ro , pa-ro , to-ro-wo 1

9 pa-ki-ja-si , pa-ro , e-ri-we-ro 3

10 e-wi-te-wi-jo , pa-ro , wi-sa-to 1

11 ]ṃẹ-te-to , pa-ro , ko-do 3

12 ro-]u-so 24

13 ]me-te-to , pa-ro , e-u-qo-ne 3

Dimensions (HEIGHT, LENGTH, THICKNESS): 15.9, 8.6, 2.0 cm.

Format: after line 7, the rulings of original lines 8–11 were erased, and new, more narrowly spaced lines were drawn for 8–13. In any case scribe uncertain and making mistakes in lines 1–3.

Line 2: pe-ri-te written smaller; pa-ro written supra in unruled line space, as if me-ta-pa caused a slight confusion as if the scribe took it to be the first sign of necessary pa-ro and leading to omission of -ro; and then, of course, necessitating writing pa-ro above line and unruled.

Line 3: -wi-jo crowded with -jo added as an afterthought.

Un(1) 267 (8; H 1)

1 o-do-ke , a-ko-so-ta

2 tu-we-ta , a-re-pa-zo-o

3 tu-we-a , a-re-pa-te [[ ]]

4 ze-so-me-no [[ ]]

5 ko-ri-a2-da-na AROM 6

6 ku-pa-ro2 AROM 6 157 + WI 16

7 KAPO 2 T 5 VINa 20 ME 2

8 LANA 2 VINb 2

9 vacat

10 vacat

11 vacat

Dimensions (HEIGHT, LENGTH, THICKNESS): 15.5, 9.0, 1.7 cm.

Condition: gouges produced by finger on the verso where clay was extracted perhaps for applying on the recto.

Format: perhaps palimpsest; present ruling of 9–11 over vestiges of an earlier ruling and text.

Line 3: original word-divider and ze-so-me-no erased at right of existing text. ze-so-me-no then written in full on line 4.

§26. The first of the two interlinks with other tablets is the personal name a3-ki-e-u, which is listed in Vn 130 line 4 in the dative at the locality a-pi-no-e-wi-jo. a3-ki-e-u appears on PY tablet Jn 605.10 (also associated with the locality of a-pi-no-e-wi-jo). On Jn.605.10 the name appears in the genitive (a3-ki-e-wo) as the owner (or responsible party) of two do-e-ro (‘slaves’) who are doing bronze work.

§27. Second, the personal name a-ta-no is listed in the dative (a-ta-no-re) in Vn 130 line 7 at the site of pa-ki-ja-ne. a-ta-no recurs on Pylos tablet Fn 50 in the context of allocations of HORD and in the genitive, i.e. presumably somehow ‘in possession of’ and therefore ‘responsible for’ or ‘identified with’ a qa-si-re-wi-ja, i.e., perhaps a group of men at work under the supervision of the qa-si-re-u.[6]

§28. I would note here that a3-ki-e-u himself is not specified as a bronzesmith (ka-ke-u).[7] But he is an individual of sufficiently high station and means to be able to allocate two do-e-ro to bronze work. This implies, of course, that he likely is capable of allocating other do-e-ro to other tasks—or the same do-e-ro to other tasks once their bronzeworking commitments were fulfilled. In any event, his indirect ‘involvement’ in bronzeworking on Jn 605 is no compelling reason to assert that the tablet Vn 130 has to do with bronzeworking or bronze vessels. See Nakassis 2013:63–66 on this thorny problem and serious downside to making transitive inferences from prosopographical tracking tablet to tablet.

§29. The DGE has this entry for ἄγγος, -εος, τό:

1 recipiente, vasija, vaso frec. para líquidos: leche Il.2.471, Od.9.222, 248, χρυσίον ἄ. Alcm.56.3, vino Od.16.13, διὲξ σωλῆνος ἐς ἄγγος Archil.14, cf. Hdt.5.12, E.El.55, IT 953, 960, Gp.7.22

•tinaja para almacenamiento indistintamente de grano, vino o pasas καὶ ἄγγεσιν ἄρσον ἅπαντα Od.2.289, ἐκ δ’ ἀγγέων ἐλάσειας ἀράχνια, καί σε ἔολπα γηθήσειν βιότου αἱρεύμενον ἔνδον ἐόντος Hes.Op.475, εἰς ἄγγε’ ἀφύσσαι δῶρα Διωνύσου Hes.Op.613, cf. h.Cer.170, βότρυας ἄγγεϊ κοίλῳ δέχνυτο Nonn.D.12.338, para bálsamo, Call.Fr.43.89, para paja y lana, Aen.Tact.29.6, 8

• ἄγγος οὐρηρόν orinal Philum.Ven.14.5.

2 urna cineraria S.El.1118

•sarcófago, IAssos 72.1 (imper.), ISelge 66.1 (III d.C.), σορίδιον ἄ. TAM 2.1164 (Olimpo III d.C.).

3 cofre, caja S.Tr.622, para guardar documentos judiciales, Arist.Fr.455

•cesta, cesto para exponer un niño, Hdt.1.113, E.Io 32, 1337, de pescado Eu.Matt.13.48.

4 panal de abejas μέλισσαι … ἄγγεα κηρώσασθε AP 9.226 (Zon.), μέλισσα … μυριότρητα κατ’ ἄγγεα κηροδομοῦσα Ps.Phoc.174.

So in historical times it seems generically to refer to ‘containers’ or receptacles without specification of shape or materials.

§30. Reason 3a: entries in Vn 130 are specified line by line by place names: the case of nine of the place names is ambiguous, but two (in entries 6, 7, 9) are clearly dative/locative sa-ri-no-te (6) and pa-ki-ja-si (7, 9). This makes it tenable that the remaining ambiguous forms are dative/locative also—and not, for example, nominative or rubric nominative. That is to say, the activities behind the entries on lines 2–13 are likely going on at those places and not being contributed from those places.

§31. Reason 3b: for each toponym (except ro-u-so on line 12 with the relatively large number 24) particular anthroponyms are registered on each line in the formula pa-ro PERSONAL NAME dative.

§32. I should note that, in regard to the ἄγγεhα recorded without ideogram on Vn 130, J.L. Melena in 1987 drew a connection, which now seems sound, between Vn 130 and Un 1320[ +]1442 (C ii). Here is part of his discussion of Vn 130:

La exigüidad de las cantidades que se asignan a cada individuo, la formula misma empleada para dicha asignación y la posibilidad de que el encabezamiento fuera ocupado por un topónimo, todo ello nos sugiere que quizá Un 1320 pueda ser puesta en paralelo con la tablilla pilia Vn 130.

Estos a-ke-a2 representan en Vn 130 el acusativo neutro plural /angeha/ “recipients”, quizá de vino (cf. Od. 16.13), quizá de cereal (cf. Hes., Erga 600), y probablemente cerámicos. Vn 130 y Un 1320 recogen, si nuestra interpretación es acertada, una distribución de estas vasijas consignadas a determinados individuos en determinadas localidades del reino de Pilo.

§33. Un 1320 is transcribed as follows:

1 ka-ra[ ]ru-wa

2 ] A 5

3 vest.[ A ]4

4 ]vest.[

5 ]jo [ A

6 pa-ro ] a-ke-ra-wo , A[ qs

7 pa-ro ]e-ri-we-ro , A 3

8 pa-ro , e-u-ka-no , A 2

9 pa-ro , ru-na , A 1

10 vacat

§34. I accept Melena’s identification of the phonogrammatic ideogram A as ἄγγος and that these receptacles are under the care, control or authority of the individuals specified in each line. Unfortunately, the heading line is broken away. I would only modify Melena’s early discussion by pointing out that a-ke-a2 in Vn 130 can be either nominative plural or accusative plural. And here on Un 1320 there is no indication of what has been done or is being done with these likely aggeha. We only know that the specified quantities were pa-ro the specific personal names.

§35. The quantities of aggeha in each line are in the same range as on Vn 130. A super-hypothetical suggestion would be to restore the opening of line 1 as ka-ra[-re-we or ka-ra[-re-wa nominative or accusative plural of the Linear B word for ‘stirrup jars’ *χλαρῆϝες.

§36. On Pylos oil tablet Fr 1184.3 ka-ra-re-we are recorded as 38 in number pa-ro an individual named i-pe-se-wa. This entry is right beneath the explicit statement that an individual named ko-ka-ro a-pe-do-ke ‘delivered, rendered, paid’ (Killen 2024:730, 930, 932) 18 full units of OLE + WE to an individual named e-u-me-de-i. This connection would be important in linking aggeha with processed, i.e. perfumed, olive oil.

In my 2014a article, I signpost that Vn 130 has some key features:

- Vn 130 has a clear connection, in its (a) dimensions and (b) shape and even (c) the manner of entering its contents (formatting and information entry) with tablet Un 267 (cf. figures 1 and 2 and the texts above);

- Vn 130.1 has a heading with the formulaic syntactical structure (o- | VERB | PERSONAL or OCCUPATIONAL NAME), comparable to other important texts introduced by o- or jo-: PY Eq 213, Pn 30, Ta 711, Un 267, Vn 10, Wa 917;

- Vn 130, through the verbal form in its heading, is also possibly connected with Un 267. The future participle form ze-so-me-no occurs on Un 267.4—see also the compound noun a-re-pa-zo-o =*ἀλειφαζόος ‘unguent-boiler’ (also on other tablets as a-re-po-zo-o). The finite verb form on Vn 130.1 is o-ze-to;

- both tablets Vn 130 and Un 267 are by “master tablet-writer” Hand 1;

- I stressed that I agree with other scholars that Palmer’s (1963:370) two original proposals, that ze-to might represent γέντο ‘got’ or κεῖτοι ‘lies in store’, are untenable. But I also acknowledged then and do so again now that the meaning of ‘got’ or ‘received’ persists in ongoing discussions.

1. Vn 130 and Un 267

§37. Our crucial starting point is that Vn 130 and Un 267 are a Stylus pair written by the same scribal hand, in fact the so-called master-scribe, Hand 1, at Pylos.[8]

§38. This is a vital point since the grouping of tablets into sets by subject matter and formulae and vocabulary is based upon or reinforced by the physical forms of the tablets and the handwriting styles on the individual tablets. I have rechecked Vn 130 and Un 267 carefully for the much-delayed definitive corpus volume Palace of Nestor IV,1 now in proof.

§39. My further study confirms that “[Un 267] is a tablet of the same dimensions and shape as Vn 130. … Both of these page-shaped tablets even have, rather uncannily, erasures and re-settings of the final lines of their texts.” And their format and manner/instincts of information entry are similar (cf. here Figures 1 and 2).

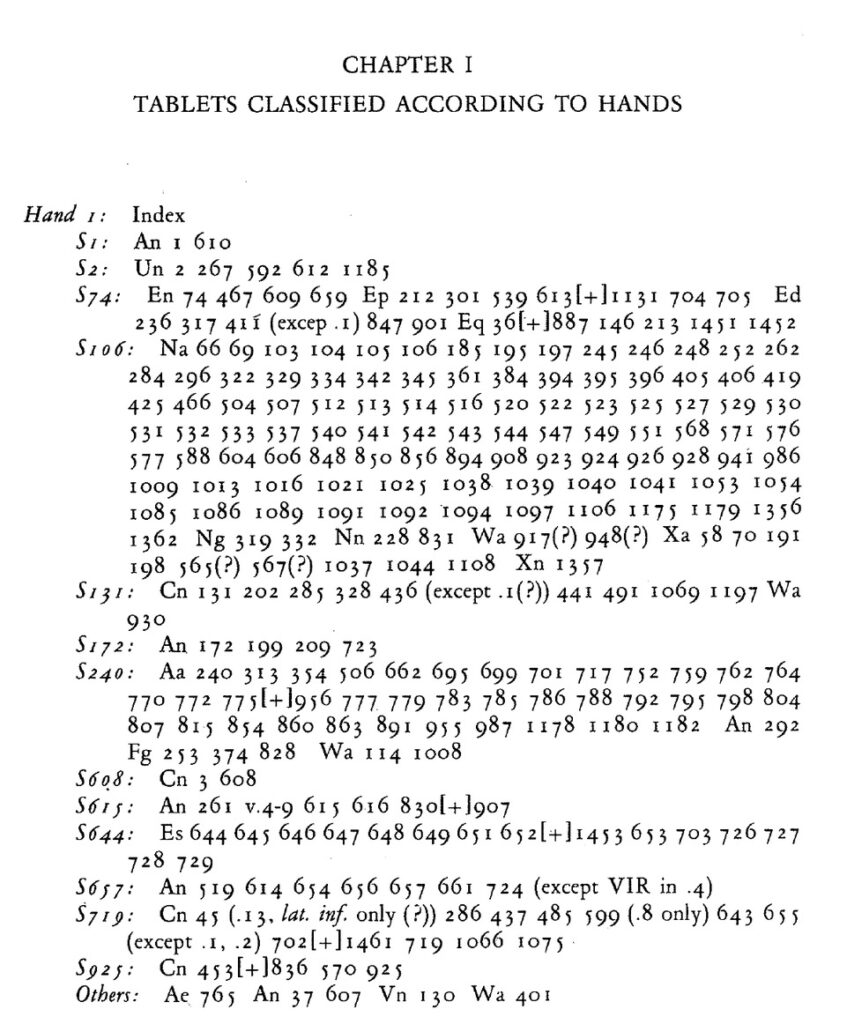

§40. More importantly, however, as can be seen in Palaima 1988:35 (see also Bennett and Olivier 1976), almost all of the 200 tablets by Hand 1 have long ago been readily placed into thirteen Stylus groups and the text series within them. Tablets/texts within these Stylus groups are often united by tablet shapes, layouts and similarities in contents (shared general subjects and specific details).

Figure 3. Tablet assignments to Hand 1 by Stylus groups (after Palaima 1988:35)

§41. The pairing of Vn 130 and Un 267 then is straightforward since in fact almost all the 200 or so tablets by Hand 1 have long been assigned to the large, important and distinctive Stylus group ‘sets’ and series written by Hand 1. These deal with livestock (Cn), rations to women’s work groups (Aa), coastal watcher texts (An), flax (Na, Ng, Nn), landholdings (En, Ep, Eq) and other topics. See Figure 3.

§42. The subject matter of Vn 130 does not adhere to the subject matters of any of these long-established groupings of texts. Thus we argue that by tablet shapes, formatting of texts, scribal hand and even vocabulary, it is possible and reasonable to pair Vn 130 with Un 267. In fact, only three (3) page-shaped tablets by Hand 1 among his two hundred tablets were heretofore unattributable to a Stylus group. See Figure 3.

§43. It is therefore impossible not to associate Vn 130 with Un 267, formerly in Stylus 2, and now together in Stylus 130. This is our bedrock. The tablets upon which texts are written are our hard evidence and our starting point. If we think about the tablets as tablets within an operating regional palatial administrative system and we take into account what I wrote in 2014a and 1988, Vn 130 and Un 267 do belong together.

§44. We should also note in passing here that in his voluminous output, Hand 1 nowhere deals with bronze per se (Jn, Ja), nor even with bronze vessels (e.g., bronze tripods in the Ta series of Hand 2) or with bronze recycling (in the Jn 829 also by Hand 2).

2. The Meaning of pa-ro

§45. The preverb/later prefix or preposition pa-ro in the Linear B period can be and is almost universally translated ‘from’. But ‘from’ is general and lacks the fuller administrative and ‘legal’ semantics of pa-ro in our texts. It also is hard to see why a preverb originally meaning ‘beside’ would come to mean ‘from’ when used with the dative or locative case. The genitive case conveys ‘origin from’ and is used in later Greek in relation to such preverbs/prepositions as ἐκ ‘out of’ and ἀπό ‘away from’ and ὑπό ‘from underneath’ and παρά ‘from the side of’. See discussion for historical Arcadian evidence.

§46. I have long translated pa-ro as uco = ‘under control, care or authority of’ (see Palaima 2000:263 and 266 with explanation).[9] This applies to its use in tablets and sealings relating to livestock management (e.g., Cn 40, 45, 418, 599), banqueting provisions (e.g., Un 138) and landholding (e.g., Ep 212, Ep 539, Ea and Eb series passim).

§47. Killen (2023:110–111) quotes correctly how I nuance (Palaima 2014a) the underlying meaning of pa-ro and how I render it as uco in my translation of the entire text of Vn 130 in the Schelmerdine Festschrift. Yet inexplicably Killen asserts that it will be “surprising to the quite numerous Mycenaean scholars” that Palaima translates pa-ro da-mo in landholding texts as “‘in’ (italics mine) the dāmos.”[10]

§48. But I do not translate pa-ro da-mo as ‘in the dāmos’. Why not? The dāmos is a locally based entity that sees to the distribution in usufruct of communally organized land. It is etymologically connected to the idea of partitioning. Cf. Lejeune 1965:6: “Dans nos textes, le damo apparait comme une entité administrative locale à vocation agricole. II possède des terres, dont une partie est morcelée et affectée en usufruit à des bénéficiaires individuels”; and Palaima 2014b:97.

§49. It is difficult to see how “‘in’ the dāmos” would make sense on a landholding record. Interested readers may consult Palaima 2000 and Palaima 2015:621–629 for detailed argumentation and documentation of landholding records and landholding terminology.[11]

§50. Killen also asserts that “pa-ro du-ni-jo following qe-te-a2 in the heading of Un 138 does not seem likelier to mean ‘chez du-ni-jo’ than ‘from du-ni-jo’. However, I translate it uco du-ni-jo. I do think, along with Olivier and Melena 1990, that ‘chez’ is closer to the real meaning here than ‘from’.[12] Here is my translation in Palaima 2000:266 concerning PY Un 138:

pu-ro , qe-te-a2, pa-ro , du-ni-jo

This tablet concerns Pylos (pu-ro) / specifically items that are ‘to be paid as a religious obligation’ (qe-te-a2) [13] / and the first batch of items is ‘under the control of’ (pa-ro) / an individual named du-ni-jo.

pa-ro is an original preverb meaning ‘beside’ or ‘next to’, and semantically when linked with nouns in the merged dative/locative in the Linear B records from Pylos means more than ‘from’. In fact, basically it still is locationally ‘beside’ (and therefore ‘within the reach, and therefore the control, of’) both in the fundamental meaning of the dative/locative case form and in the inherited basic meaning of pa-ro.

§51. In Mycenaean Greek pa-ro is used with dative forms in specific contexts dealing with transactions like landholding and the providing of sacrificial animals for rituals and feasting ceremonies.

§52. In both cases here, landholding and providing animals for sacrificial feasting, the meaning I am proposing gives a fuller understanding of what is going on than ‘from’ or ‘by’.

§53.1 So and so holds land “under control, care or authority of X” (X = personal name or da-mo) comes closer to the situation in the landholding texts. These landholding documents are not dealing with the transmission of ownership of a parcel of land but of holding—as Lejeune explained way back when—in usufruct depending on conditions of past and ongoing service.

§53.2 e-ke means ‘holds’ land, either as a reward for past or anticipated service or under particular current and future obligations and conditions. If the understood services or fulfilments of obligations fail, the landholding we assume reverts to the object of pa-ro. So pa-ro implies more than simply ‘from’ in landholding documents. It makes clear the ultimate continuing responsibility for the use of the land that is ‘leased’ or ‘sub-leased’ out.[14]

§54. Likewise, livestock that are brought in for sacrifice and later feasting sometimes come with enough fodder for 30 days (TH Wu 46, Wu 56, Wu 76) of maintenance to keep them in o-pa (‘finished’) condition. If the livestock are specified as qe-te-a2, they are being delivered as a kind of fine or compensatory payment (Thompson 2024) and most likely are cared for with the fodder “under control, care or authority of, for example, du-ni-jo.” pa-ro can be reduced to ‘from’ with the loss of the underlying implications that I explain.

§55. The pa-ro phrase is a nuanced and, as it were, ‘legal’ terminology. In one case, it specifies who truly has primary use of the land and retains ultimate continuing responsibility for it (again whether the da-mo or the individual named after pa-ro).

§56. In the other case here (sealings and animals for sacrifice and the tablet that records information derived from sealings), pa-ro conveys ‘under whose authority and care and in whose interests’ the animals are being transmitted into the sphere for ritual/ceremonial use—and, of course, who will get credit for so doing. I clearly explain this in Palaima 2000 and (in abbreviated form) in Palaima 2014a.

§57. Next let us consider the meaning of the verb form in the heading of tablet Vn 130. Killen (2023:108) argues that -ze-to must have a meaning of ‘received’ not because of Leonard Palmer’s early and now untenable interpretation of ‘got’, but because, in Killen’s opinion, heading phrases with jo- and o-, under certain further conditions such as having a personal name in the header phrase, in most cases fall into two basic categories (italics mine): ‘receiving’ and ‘giving’ ‘from’ and ‘by’ the centre.”[15]

§58. The sample pool here consists of five tablets—six if we include the tablet in question Vn 130 itself. So I think we should ask what weight does the claim “in most cases” have in our reasoning?

§59. Vn 10 and Jn 829 do not have a personal name in the header phrase. And on Vn 20, the personal-name word-unit in question pa-ra-we-wo is, according to Killen 2024:1005 “obscure” or, p. 545, unclear “[n]on liquet.” Even if pa-ra-we-wo is a personal name, the referend is in the genitive and ‘in possession of’ the commodity, so it does not function as an agent in the activity which the tablet is recording. So only in two of the five selected tablets, three of six if we include Vn 130 itself, do we have a personal name.

§60. I bring this point up for two reasons. First, in Mycenology, it is tempting to make ‘rules’ from sample pools so small that no statistician would deem them credible or valid. Second, in the current case, there are other texts to consider and there is also a need to ‘begin from the associated pair of tablets’ that I have identified by form, Hand and—I would argue—subject matter.

§61. Killen relies on the assertion that tablets with jo- and o- fall into two basic categories if we add other specifications. If we do not, I would cite here a tablet that falsifies the ‘rule’. Tablet Cn 608 begins jo-a-se-so-si, si-a2-ro o-pi-da-mi-jo which reads ‘thus the o-pi-da-mi-jo will fatten’ (jo-a-se-so-si asēsonsi meaning, Ventris and Chadwick 1973:534, and Killen 2024:935, “thus they will fatten” vel sim.). And then the nine main districts are listed, three unambiguously in the dative-locative, where the fattening process will take place.

§62. If we expand our scope to include other o- and jo- headed tablets, on Ta 711 and Eq 213 heading phrases begin o-wi-de in reference to ‘seeing’ during an inventory and ‘inspecting’ during a ‘tour’ of land parcels. So there are clearly more than two basic categories for headings of this kind. There are at least four. And this range of alternatives is within the work of the same scribes.

§63. We should also add, however, that there is in the standard heading vocabulary a basic verb for ‘receiving’: sigmatic de-ka-sa-to KN Le 641, PY Pn 30.1, and athematic de-ko-to KN Le 642, both from δέχομαι. This verb is not used here. And given the two additional attested categories of actions like ‘fattening’ and ‘seeing’ and ‘inspecting’, we should at least entertain the idea that ze-to means something else besides an unexplainable alternative to the standard word for ‘receive’ attested at Knossos and Pylos.

§64. Killen 2023 does not posit what verb ze-to might be. Nonetheless, Chadwick in Ventris and Chadwick 1973 cites Palmer 1963:440 as support for the tentative interpretation as ‘received’.[16] My proposal for -ze-to in Palaima 2014a, N.B. having identified the ‘pairing’ of Vn 130 and Un 267, was to link o-ze-to with ze-so-me-no (and a-re-pa-zo-o) on Un 267. ze-so-me-no is clearly the future medio-passive participle of ζέω ‘boil’ and Un 267 is clearly a text having to do with unguent boiling.

§65. In Palaima 2014a, I relied on the most current suggestion (Melena 2014) that the verb form ze-to on Vn 130 is either (1) aorist ō(s) dzesto (for the type of aorist, compare εὖκτο, δέκτο, and γέντο) “thus he boiled, seethed,” or (2) athematic present ō(s) dzestoi “thus he is boiling, seething.” Melena’s and my line of interpretation of the form and the tablet is also accepted by Lane (2016:49) and Piquero-Rodriguez (2019:236).

§66. Again I propose the obvious as a working hypothesis, namely that Hand 1 on both of two tablets of the same size, shape and format is dealing with the verb represented by ze-. So I pursued whether ze-to is related to ze-so-me-no and a-re-pa-zo-o on Un 267.

§67. Now there are objections to interpreting ze-to as an athematic form. Such a form is not historically attested for ζέω < *yes-. As Jeremy Rau explains (pers. comm. 10.04.2024) the forms cited as parallels for dzesto occur with verbs that are middle/deponent in the present tense (εὔχομαι, δέχομαι, γίγνομαι). ζέω is not.

§68. Taking this into account, I now suggest that the spelling ze-to is the result of the scribe hastily omitting the -e- between ze and to, and so read ze-<e->to,

either as a present dze-<he>toi

or as an augment-less imperfect dze-<he>to

of the verb ζέω.

§69. This new proposal gains support because the context here is ideal for interpretation as a ‘causative middle’ indicating that, as Rau explains, “the subject is indirectly involved in the carrying out of the verbal activity or causes someone else to do it.”

§70. We also have seen above in the notes to our transcriptions of Vn 130 and Un 267 that in both texts the scribe misfires in entering information on lines 2 and/or 3. Omission and/or correction of information in a header or opening line is not uncommon (cf. PY An 128, An 519, An 852, An 1281, Cn 40, Cn 131, Cn 254, Cn 418, Cn 599, Cn 643 etc.). The omission of -e- here is an understandable mistake especially given the repetition of /e/.

§71. A ‘causative middle’ form would fit the situation here. The figure ke-sa-do-ro in the heading phrase ze-to = ‘causes the perfumed oil boiling to be set in motion’ in his own interests vis-à-vis the palatial center. In eleven of the following twelve lines individuals in charge in different localities are specified as pa-ro (= uco), i.e., they see to the production of the specified number of ‘containers’ of scented oils at their separate sites. The site of ro-u-so is also somehow ‘under the care or concern of’ ke-sa-do-ro in meeting his responsibility for palatial interests. ro-u-so produces the large quantity of 24 a-ke-a2. The wildlands in this district (ro-u-si-jo a-ko-ro) produce large cut timbers for the chariot joinery clearing-house or workshop at the Palace of Nestor (PY Vn 10) (Palaima 2014b:97–98). There is a good supply of wood or firewood readily available in this district.

§72. The opening phrase then means ‘thus ke-sa-do-ro is causing the boiling’ or ‘thus ke-sa-do-ro was causing the boiling’ (sc. in the scribe’s mind ‘according to my [i.e., the scribe’s] knowledge’, however acquired). Essentially this is shorthand for: ‘he is in the process of seeing to making/producing perfumed unguent in the following places under the care of the named parties’.

§73. In Linear B times, imperfect forms in an augment-less stage are identical with some present forms. In the early days of Mycenaean studies, imperfects were entertained (see Aura Jorro passim).[17] They were gradually forgotten as alternatives and an unspoken rule has developed that there are no imperfects in our extant Linear B texts. But that needs to be reconsidered.

§74. Lastly here we should note that Killen, taking a-ke-a2 as the direct object of -ze-to objects that in historical times the verb ζέω is used with liquids as a direct object, not solid containers. While I have not done an exhaustive search, in Iliad 21.362 a lebēs ‘boils’ standing in for its contents:

ὡς δὲ λέβης ζεῖ ἔνδον ἐπειγόμενος πυρὶ πολλῷ

§75. ζεῖ in this Homeric line is translated in the LSJ as ‘as the kettle boils’, i.e., not the substance within it. Thus there is no impediment in ancient Greek to a pot boiling, nor, therefore to boiling a pot. This is a natural metonymic usage seen in our polite question, “Shall I boil/brew/make us a pot of coffee—or tea?”

§76. 4.-5. The late Pierre Carlier and I (Palaima 2014: 88; Carlier 1995:356) long ago pointed out that the central palace at Pylos interacts with the *qa-si-re-we ‘occasionally’ in fulfilling palatial needs for finished bronze products. Recycling document Jn 829 speaks to products like bronze points of javelins and spears and bronze end-covers for wooden spear and javelin shafts.

§77. What Carlier and I were both stressing is that the *qa-si-re-we (‘chieftains of surrounding villages’, ‘local headmen’; Ventris and Chadwick 1973:359 and 576) and the many individuals with and for whom they managed the allotment of small portions of bronze ingots would have had other types of work to manage and perform locally for themselves, for their local communities, for the district capitals and for the central palace often simultaneously during the calendar year.

§78. Thus the palatial centers would be interacting with *qa-si-re-we ‘on one or another economic occasion’ in which the palatial center had an interest. That is to say, the *qa-si-re-we were not exclusively palatial agents, nor were they exclusively bronze ‘guild leaders’ or palatial ‘work mobilizers’. In this we fully agree with Shelmerdine (2008:135): “It is likely, therefore, that these officials really derived their power from local communities, one part of a non-palatial hierarchy partly [viz. ‘occasionally’] assimilated and used by the central administration.”

§79. Killen (2008:194) catalogues conservatively an ample list of ‘industrial’ activities taking place throughout the seasonal calendars in the Mycenaean palatial territories. The six well attested are:

- textile production, including dye-making;

- bronze working;

- N.B. production of perfumed unguents;

- production of chariots, chariot wheels and weapons;

- leatherworking.

This understandably leaves out agricultural production of grains, arboricultural production of figs and olives and eventually olive oil, and viticultural production of grapes and eventually wine.

§80. Other activities are known through trade names. These include the following:

- pottery production;

- bow-making;

- gold-working;

- ship construction;

- carpentry;

- house and wall building; and

- working of precious materials like ku-wa-no and ivory.

We would add in here all the work entailed by gathering and converting raw materials for manufacturing, e.g., the cutting and retting of flax for linen; the shearing and cleaning of raw wool for the making of thread and eventual weaving; the gathering of flowers, herbs and resins (terebinth) for perfuming oil; the cutting (du-ru-to-mo) and selection of wood pieces for chariot axles (PY Vn 10).

§81. Perfumed unguent manufacture is one of Killen’s ‘big six’ well-attested industries. This increases the likelihood that the Stylus pair Vn 130 and Un 267 join the other texts and series related to this economically vital industry for Mycenaean participation in international trade. The Mycenaean palatial territories needed to keep the widely dispersed Mycenaean stirrup jars full of their internationally desired product: perfumed oil (Haskell, Jones, Day, and Killen 2011).

§82. A basic requirement for perfume manufacture and for bronze-casting is access to wood fuel for smithing metals and for boiling perfumes. Both can be done best in areas where the raw materials (ingot or scrap metal; oil, fixatives and flower and plant scent ingredients) are readily available and workable.

§83. The key word a3-to-pi in the heading of Vn 130 is not found in the Glossary of Killen 2024:940. We posit that it is an instrumental of an o-stem noun αἶθος ‘fire log’, stipulating that the individuals in question have and are using local firewood resources to do the boiling.

§84. Peter Warren, based upon his extensive study (Warren 2014) of what flowers were located where, and of what else is needed in order to produce, for example, Linear-B-attested rose-scented or rose-infused (enfleurage) oil (wo-do-we: Piquero-Rodríguez 2019:414; Killen 2024:1052), sent me this personal communication (09.24.2014):

Working from your paper I take it that ze-to implies that boiling is taking or has taken place at all these various locations. I think there may be a very good reason for these localized operations, namely that the cultivation of the perfume plants, especially roses, was taking place there. There would then have been local harvesting and thus have been no need to transport cut (rose) flowers around; on the spot manufacture would have enabled fragrances to be retained. Naturally details of the operations would have been reported to, or were required to be reported to, the centre (Pylos, but cf. also the relevant Knossian tablets too).

§85. Given the variety of economic interests represented in the tablets, there is no need to assume that when one single name appears as an owner/allocator of two ‘slaves’ (do-e-ro) in what is clearly a bronze allotment tablet (Jn 605) and another single name appears with his qa-si-re-wi-ja in a tablet allotting quantities of grain (HORD Fn 50) and both then recur as two of eleven names in a longer list on another tablet of heretofore unspecified purpose (because of the heretofore inscrutable nature of the heading verb and lack of ideograms) and subject (Vn 130), that the third tablet has to do with bronze.

§86. a-ta-no appears in the dative on Vn 130.7 and in the genitive as possessor or holder or leader or at least namesake of qa-si-re-wi-ja on Fn 50.3. Fn 50 is a text dealing with HORD allotted to three qa-si-re-wi-ja at the start and then to two individuals identified by personal names and then to nine occupational terms including a ‘superintendent of honey’ me-ri-du-<ma->te, a ‘hide-bearer’ (di-pte-ra-po-ro), a ‘bread-baker’ (a-to-po-qo), an ‘overseer of τεύχεα’ (o-pi-te-u-ke-e-we), plural ‘draft-animal-pair-drivers’ (ze-u-ke-u-si) and four groups of ‘slaves’ (do-e-ro-i) identified by personal names in the genitive. There is no indication of what economic interest(s) the qa-si-re-wi-ja of a-ta-no is serving on Fn 50.

§87. a3-ki-e-u appears on Vn 130.4 and also is recorded on Pylos tablet Jn 605 (a text having to do with the allotment of bronze and reckoning of bronze workers) as an owner of two do-e-ro (‘slaves’) at the same site (a-pi-no-e-wi-jo) as on Vn 130.

§88. Because these two out of eleven individuals on Vn 130 show up, one on a Jn tablet, the other on an Fn tablet, Killen proposes that the aggeha on Vn 130 are made of bronze. Note that Palmer (1963:370) wanted to connect Vn 130 with bronze in a vague way because of the two tenuous intertextual links.

§89. But there is no indication on Vn 130 (or on Un 1320) as to what material the receptacles are made of. To single out one individual in the text and use an entry in another text recording the periodic involvement of this individual’s slaves in bronze working as a determining factor is problematic. And of course, this is interpreting Vn 130 removed from its context as one of a pair with a record, Un 267, clearly in the perfumed oil sphere.

§90. A qa-si-re-u undoubtedly could mobilize local men and women to perform tasks for the palatial centers in all sorts of economic areas.

§91. Bronze working would not be continuous. This is especially so in the disturbed economic conditions of the last year of the palace when most of the Pylos texts were written. The piecemeal apportioning of the raw material for bronze working would depend upon obtaining bronze ingots through, in that period, irregular trade and standard redistributing of collected scrap bronze (Jn 829).

§92. A qa-si-re-wi-ja (if taken as a work group headed by a qa-si-re-u) could be put to all kinds of work as circumstances dictated. There is no conflict of interest for a3-ki-e-u to have two slaves at work on bronze on Jn 605 and for a3-ki-e-u to be involved in working on unguent boiling in the same rural area on Vn 130.

§93. In attending to the palatial needs of bronze production intermittently, there is plenty of opportunity for qa-si-re-we and their labor forces to do service for the palatial center in several areas.

3. Conclusion

§94. In conclusion, the clear and simple pairing of Vn 130 and Un 267 by Hand 1 must be the starting point of all future work associated with these two Pylos tablets.

§95. Both tablets deal with the major perfumed oil industry attested in the Linear B tablets from Pylos in the late palatial period in Bronze Age Messenia.

§96. The heading of Vn 130 puts it in company with other headings beginning in o- and jo-. The evidence that the verbal form in Vn 130 has to mean ‘receive’ or collect’ is tenuous at best and relies on dubious statistics.

§97. The main verb in the explanatory heading on Vn 130 can readily be interpreted as related to the same verbal root found in a participial form and a compound noun form on its archivally linked text Un 267: ζέω = ‘boiling of oil’ in the making of ‘perfumed unguent.’

§98. The form -ze-to is reasonably interpreted as a slip in the normal Linear B spelling, an error common enough in the first three lines of important page-shaped tablets at Pylos where we find a good many erasures and corrections, because even accomplished scribes were getting started on making a record.

§99. A middle form as causative middle (present or imperfect) is well-suited to the context of Vn 130 and Un 267. The imperfect tense was proposed for a good number of verb forms in the early days of Mycenaean studies, and although it has fallen into explanatory disuse, it perhaps should be reexamined.

§100. The specification of individuals involved in the unguent boiling by means of the preposition pa-ro and the dative case is clear, as it is in other areas of the regional economy, including landholding. uco = ‘under the care, authority or control of’ is a fuller nuancing of the implications of pa-ro plus the dative in the series where this formula is used.

§101. There is no compelling reason to refute these hypotheses because one out of eleven individuals involved in the perfumed oil production on Vn 130 elsewhere has two of his slaves working for an unspecified time on small-scale bronze-working.

§102. If a qa-si-re-wi-ja is a work group directed by a qa-si-re-u, there is no implication in the term itself that the work done by the individuals in the qa-si-re-wi-ja has to be bronze-work.

§103. There is no convincing evidence that the containers on Vn 130 are made of bronze. Nor is there any evidence that they are not made of bronze. They would, however, seem to be common enough receptacles to need no explicit notation as to their size, shape and material via ideogram on tablet Vn 130.

§104. There is one other byproduct of my reconsideration of PY Vn 130 and Un 267. It is clear that hypothesizing the subject matter of problem texts by intertextually tracking the names shared between tablets is much more tenuous than its practitioners make it out to be, especially if they ignore what the palaeographical and epigraphical evidence tells us about the relationships among Linear B tablet and sealing records. Scholars should be wary of general rules derived from selectively chosen small sample groups of texts.

Palaima’s Bibliography

Aura Jorro, F. 1985. Diccionario micénico. Vol. 1. Madrid.

———. 1993. Diccionario micénico. Vol. 2 Madrid.

Bennett, E. L., Jr. and J.-P. Olivier. 1976. The Pylos Tablets Transcribed II. Incunabula Graeca 59. Rome.

Bennet, J., A. Karnava, and T. Meissner, eds. 2024. KO‑RO‑NO‑WE‑SA: Proceedings of the 15th Mycenological Colloquium, September 2021. Ariadne Supplement Series 4. Rethymnon.

Beekes, R. 2010. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. 2 vols. Leiden.

Carlier, P. 1995. “Qa-si-re-u et qa-si-re-wi-ja.” In Laffineur and Niemeier 1995:355–365.

Chantraine, P. 2009. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grec. Histoire des mots achevé par Jean Taillardat, Olivier Masson et Jean-Louis Perpillou, avec en supplément, les Chroniques d’étymologie grecque (1–10) rassemblées par Alain Blanc, Charles de Lamberterie et Jean-Louis Perpillou. Paris.

Companion 1 = A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Vol. 1. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 120, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies. Louvain-la-Neuve. 2008.

Companion 2 = A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Vol. 2. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 127, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies. Louvain-la-Neuve. 2011.

Companion 3 = A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Vol. 3. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 133, ed. Y. Duhoux and A. Morpurgo Davies. Louvain-la-Neuve. 2014.

Davis, J. L. 2022. A Greek State in Formation: The Origins of Civilization in Mycenaean Pylos. Sather Classical Lectures 75. Oakland.

Davis, J. L., S. R. Stocker, S. Vitale, J. Bennet, H. Brecoulaki, and A. P. Judson. 2024. “The Date of the Final Destruction of the Palace of Nestor at Pylos.” In Bennet, Karnava, and Meissner 2024:521–537.

Del Freo, M. and M. Perna. 2016. Manuale di epigrafia micenea. 2 vols. Padua.

Duhoux, Y. 2008. “Mycenaean Anthology.” In Companion 1:201–397.

Haskell, H. W., R. E. Jones, P. M. Day, and J. T. Killen. 2011. Transport Stirrup Jars of the Bronze Age Aegean and East Mediterranean. INSTAP Prehistory Monographs 33. Philadelphia.

Killen, J. T. 2008. “Mycenaean Economy.” In Companion 1:191–195 (159-200).

———. 2023. “A Pot-boiler at Pylos?” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici, n.s., 9:107–114.

———. 2024. The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Cambridge.

Laffineur, R. and W.-D. Niemeier, eds. 1995. Politeia: Society and State in the Aegean Bronze Age; Proceedings of the 5th International Aegean Conference / 5e Rencontre égéenne internationale, University of Heidelberg, Archäologisches Institut, 10–13 April 1994. Aegaeum 12. 2 vols. Liège.

Lane, M. 2016. “Returning to Sender: PY Tn 316, Linear B i-je-to, Pregnant Locatives, *perH3-, and Passing Between Mycenaean Palaces.” Pasiphae 10:39–90.

Lejeune, M. 1965. “Le damos dans la société mycénienne.” Revue des Études Grecques 78:1–22.

Melena, J. L. 1987. “Notas de filología micénica, II: ¿Qué se asienta en PY Un 1320 [+] 1442?” In Athlon. Vol. 2, ed. P. Bádenas de la Peña, A. Martínez Díez, M. E. Martínez-Fresneda, and E. Rodríguez Monescillo, 613–618. Madrid.

———. 2014. “Mycenaean Writing.” In Companion 3:1–186.

Nakassis, D. 2013. Individual and Society in Mycenaean Pylos. Mnemosyne Supplements 358. Leiden.

Palaima, T. G. 1987. “Mycenaean Seals and Sealings in Their Economic and Administrative Contexts.” In Tractata Mycenaea: Proceedings of the 8th International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, Held in Ohrid, 15–20 September 1985, ed. P. H. Ilievski and L. Crepajac, 249–266. Skopje.

———. 1988. The Scribes of Pylos. Incunabula Graeca 87. Rome.

———. 1995. “The Last Days of the Pylos Polity.” In Laffineur and Niemeier 1995:623–633, plate LXXIV.

———. 2000a. “The Palaeography of Mycenaean Inscribed Sealings from Thebes and Pylos, Their Place within the Mycenaean Administrative System and Their Links with the Extra-palatial Sphere.” In Minoisch-mykenische Glyptik: Stil, Ikonographie, Function, ed. W. Müller, 219–238. Mainz.

———. 2000b. “Transactional Vocabulary in Linear B Tablet and Sealing Administration.” In Administrative Documents in the Aegean and Their Near Eastern Counterparts, ed. M. Perna, 261–276. Turin.

———. 2000c. “Θέµις in the Mycenaean Lexicon and the Etymology of the Place-Name *ti-mi-to a-ko.” Faventia 22.1:7–19.

———. 2003. “‘Archives’ and ‘Scribes’ and Information Hierarchy in Mycenaean Greek Linear B Records.” In Ancient Archives and Archival Traditions: Concepts of Record-Keeping in the Ancient World, ed. M. Brosius, 153–194. Oxford.

———. 2006. “FAR? or ju? and other interpretative conundra in the new Thebes Tablets.” In Die Neuen Linear B-Texte aus Theben, ed. S. Deger-Jalkotzy and O. Panagl, 139–148. Vienna.

———. 2011. “Mycenaean Scribes, Scribal Hands and Palaeography.” In Companion 2:33–136.

———. 2014a. “Pylos Tablet Vn 130 and the Pylos Perfume Industry.” In KE-RA-ME-JA: Studies Presented to Cynthia W. Shelmerdine, ed. D. Nakassis, J. Gulizio, and S. A. James, 83–90. Philadelphia.

———. 2014b. ““Harnessing phusis: The Ideology of Control and Exploitation of the Natural World as Reflected in Terminology in the Linear B Texts Derived from Indo-European *bheh2u- ‘grow, arise, be’ and *h2eg-ro- ‘the uncultivated wild field’ and Other Roots Related to the Natural Environs,” PHYSIS. Aegaeum 37, ed. G. Touchais, R. Laffineur and F. Rougemont, 93–99. Austin.

———. 2015. “The Mycenaean Mobilization of Labor in Agriculture and Building Projects: Institutions, Individuals, Compensation, and Status in the Linear B Tablets.” In Labor in the Ancient World, ed. P Steinkeller and M. Hudson, 617–648. Dresden.

———. 2017. “Emmett L. Bennett, Jr., Michael G. F. Ventris, Alice E. Kober, Cryptanalysis, Decipherment and the Phaistos Disc.” In Aegean Scripts. Incunabula Graeca 105. Vol. 2, ed. M.-L. Nosch and H. Landenius-Enegren, 771–788. Rome.

———. 2020. “Porphureion and Kalkhion and Minoan-Mycenaean Murex Dye Manufacture and Use.” In Alatzomouri Pefka: A Middle Minoan IIB Workshop Making Organic Dyes, ed. V. Apostolakou, T. M. Brogan, and P. P. Betancourt, 123–128. Philadelphia.

———. 2022. “Pa-ki-ja-ne, Pa-ki-ja-na, Pa-ki-ja-ni-ja.” In TA-U-RO-QO-RO: Studies in Mycenaean Texts, Language and Culture in Honor of José Luis Melena Jiménez. Hellenic Studies Series 94, ed. J. Méndez Dosuna, T. G. Palaima, and C. Varias García, 173–196. Cambridge.

———. 2024. “Historical Reflections on the Pylos Ta Series: Putting te-ke in Its Place.” In Bennet, Karnava, and Meissner 2024:449–466.

Piquero-Rodriguez, J. 2019. El Léxico del Griego Micénico: Index Graecitatis. Paris.

Palmer, L. R. 1963. The Interpretation of Mycenaean Greek Texts. Oxford.

Piteros, C., J.-P. Olivier, and J. L. Melena. 1990. “Les inscriptions en Linéaire B des nodules de Thèbes: La fouille, les documents, les possibilités d’interpretation.” Bulletin de Correspondance Hellénique 114:101–184.

Shelmerdine, C. W. 1985. The Perfume Industry of Mycenaean Pylos: Studies in Mediterranean Archaeology. Göteborg.

———. 2008. “Mycenaean Society.” In Companion 1:115–158.

Thompson, R. 2024. “Mycenaean qe-te-o and Greek Adjectives in -τέος and *-eyo-.” In Bennet, Karnava, and Meissner 2024:483–496.

Ventris, M., and J. Chadwick. 1973. Documents in Mycenaean Greek. Cambridge.

Warren, P. 2014. “Aromatic Questions.” Κρητικά Χρονικά 24:13–41.

Discussing Palaima’s talk “First Principles and Research Strategies in Mycenology”

§105. Roger Woodard opened the discussion by praising Palaima’s analysis of o-ze-to. Additionally, Woodard noted that the same usage of pa-ro, as argued for by Palaima, can be noted in Arcadian.

§106. José Miguel Jiménez Delgado stressed that he was particularly tantalized by the interpretation of *34-to-pi, which implies that that *34 is the equivalent to a3.

§107. Tom Palaima replied that a3 is equivalent to ai, so one would have αἶθος, interpreted in the plural as ‘fire logs’ with ai-to-pi being a masculine noun. Palaima added that Melena in BCILL 183 (2014:13, 16, 22, 59, 75, 82, 83, 88, 95, 113, 182) lays out the arguments for *34 = *35 = ai. Specifically, “Filling Gaps in the Mycenaean Linear B Additional Syllabary: The Case of Syllabogram *34,” in Homenaje a Manuel García Teijeiro, Valladolid 2013:211-230.

§108. Delgado remarked that this interpretation (*34-to- = αἶθος) is better than taking -to- as the agent suffix -τορ- with o-grade. He concluded that he agreed with this interpretation.

§109. Tom Palaima observed that with this interpretation, it is possible to see that these activities surrounding unguent-boiling were taking place mainly in remote locations. He then pointed out that ro-u-so with 24 aggeha on Vn 130 is noteworthy. Text Vn 10 records the ro-u-si-jo a-ko-ro, or the Lousian wild lands, from where raw timber items were delivered to the *a-mo-te-jo, he remarked. He highlighted that this refers to the forested areas, which supplied the materials needed for the general chariot workshop, and chariot and wheel construction and repair. These localities were essentially woodlands and wild fields, he concluded.

§110. Palaima then remarked that, well after the publication of his 2014 article, Peter Warren read it and noted that the production of such oils was thought not to take place at the central palace because they were, for example, rose-scented—and flowers and other locally grown plant infusions were used. Palaima then explained that in early LH III C there was no ‘FedEx’ fast transport, so by the time flower petals were transported to a central location, much of their aroma would have been lost. Thus, he inferred, it is logical to suggest that these remote locations, rich in timber, including firewood, and other natural resources, were where a good bit of the boiling and scented oil production occurred. And according to Warren’s view, even plots of roses and such were cultivated, he added. Palaima concluded that their proximity to both timber and aromatic substances made these wild areas ideal for such production processes.

I have been reading your excellent contribution to Cynthia’s Festschrift. It is one of those chance timings that I did not know of your paper when I was writing the attached: “Aromatic Questions,” Κρητικά Χρονικά ΛΔ´ (2014), 13-41. But it turns out that a possible and rather nice support for your argument emerges. One of the main points in my paper was to propose, in following up the work of my good friend Christos Boulotis, that the Minoan and Mycenaean perfume plants, notably roses, were not άγρια (as Christos took it) but cultivated. Since (Vn 130) ze-to implies that boiling is taking or has taken place at the various locations a very good reason for such localized operations would be that the cultivation of the plants was taking place there. Thus, there would have been no need to transport quantities of cut roses any distance from the cultivation plots (actions which would have soon reduced their aromatic properties).

Peter Warren (pers. comm. January 14, 2016).

§111. Delgado observed that an important point of Palaima’s work is the formal similarity between the two tablets.

§112. Palaima replied that his interpretation will now evoke further discussion and praised the MASt Seminars for giving scholars the chance to test ideas and get feedback before moving forward with further research.

§113. Elena Džukeska stated that she agreed with Palaima’s analysis of the pa-ro case, which seemed sound to her.

§114. Palaima replied that he revisited Lejeune’s monumental article “Le dāmos dans la société mycénienne” written February 1965 and appearing in REG 78 (pp. 1-22). In that article, he explained, Lejeune nuances finely what dāmos might mean in its different contexts within our tablets. However, Palaima highlighted, the question remains: does it carry the same range of meanings as it does in 5th-century Athens or what are its meanings in the late Mycenaean palatial period?

§115. Palaima continued by observing that most scholars would agree that the root of dāmos refers to an Indo-European concept of partitioning, separating things out. It represents, he clarified, an organization that can speak for itself, as we see in the E- series with the phrase da-mo-de-mi , pa-si, which seems to indicate control over land partitioning. Palaima then noted that the land, in these contexts, appears to be held (e-ke) in usufruct under specific conditions: e.g., individuals hold parcels of land because of their status, such as they are a priestess performing a particular service, or a shepherd for the lawagetas, for example. There is a wide range of roles involved, he noted.

§116. Palaima observed that, fortunately, there is always room for discussion in the MASt seminar because it creates a space for thinking, allowing the presenters and participants to reflect on what has been said during the discussion. Later either can contribute more or add to the conversation. It is really a wonderful forum to receive valuable feedback, he concluded.

§117. Jiménez Delgado clarified that he believed, based on Palaima’s interpretation, that Palaima himself did not agree with the alleged ablative meaning of pa-ro plus dative in Mycenaean and, therefore, he did not agree with the dialectal connection between Arcadian or Arcado-Cypriot and Mycenaean.

§118. Palaima deferred to Roger Woodard.

§119. At this point, Woodard pointed out that pa-ro used with the dative is attested in Arcadian.

§120. Pierini asked Palaima whether he could observe any variations in the chronology or geographical distribution of the tablets. Since not all tablets are synchronic, it is important not to expect a level of consistency that is virtually impossible, given the nature of the material.

§121. Palaima agreed that the chronology of the tablets is crucial. He explained that variations can be observed, for instance, within the work of the scribes who were active in Pylos, where it is possible to see that not only different scribes would spell certain words differently, but also that one scribe would change his own spelling and even traits in his handwriting in small ways at different points. There are tablets that come from non-final-destruction contexts. The texts under discussion here are from the final-destruction horizon.

§122. One word that stands out—Palaima continued—is certainly a-re-pa-zo-o by Hand 1, who also sometimes writes a-re-po-zo-o, with this alternation a/o being often explained as the result of different outcomes of an original sonant.

§123. Palaima then wondered: why the absence of an ideogram on Vn 130? If Melena is correct, on Un 1320 the scribe would be using /a/ = A to stand for aggos, and that would be by a scribe from Class ii, and thus clearly not by Hand 1.

§124. Palaima added that, on tablet Un 1320, no ideogram is used. This might suggest that an ideogram does not exist for this type of container, he argued. The relevant lemma in the Spanish-Greek dictionary (DGE) received some input from Martin Ruipérez. The word itself is connected to milk and wine, but also to cereals, beehives, and honey pots, and this caused Palaima to wonder whether this might not be a generic word for a receptacle or an object of that kind, and not a container having a very specific shape (as with other words referring to specific vases).

§125. Palaima also added that, during a hike through Attica with Eugene Vanderpool in the 1970s, he found a pithos sherd scored on the inside with a wavy pattern on the outside, and realized on that occasion that, in various cultures, beehives are simply ceramic pots designed for lying on their sides or upright, and they did not have an absolutely diagnostic shape, but rather certain necessary features. Still, it is doubtful whether the shape used for a beehive would be the same as that used for a wine container or a container to store grain. See Harassis, H. V. 2017. “Beekeeping in Prehistoric Greece.” In Beekeeping in the Mediterranean from Antiquity to the Present. Eds. F. Hatjina, G. Mavrofridis, and R. Jones. Nea Moudania.

§126. Therefore, there is a possibility that, in the case of Un 1320, we would have a container that is not identified by a specific ideogram: every native speaker would understand from the context the particular shape that was being described or assumed in each case, although we do have instances in which particular kinds of vases are connected to particular kinds of products, Palaima concluded.

§127. Pierini asked about possible parallels with alphabetic Greek, especially as related to land-holding.

§128. Palaima thought about the pre-classical period and especially the Solonian seisachtheia, which was the freeing of the land from the horoi. These are inscribed stones specifying the identity of the person who has a claim to the land that is technically under the control of a particular clan group and a particular family within a clan group, when land was still inalienable, Palaima specified. This is where we find mention of the hektemoroi, who might have gotten five-sixth of the produce having had to give away one-sixth of the produce and effectively became bonded servants of the people who held these mortgages, Palaima added. Thus, in these landholding records of the palace, the term pa-ro seems to have a legal connotation, something like ‘conditional’ ownership of and responsibility for specific land parcels—he remarked.

§129. To explain his point with an example from today’s life, Palaima analogized a situation like the myth of current ‘home ownership’ in the United States, where a person might have paid off their mortgage and not be beholden to a bank, but would still be beholden to the city, or the state, or the federal government for what are called property taxes; if these do not get paid, these institutions might foreclose on the person and seize their property, Palaima noted. Thus, ownership is just a notion—an illusion—he stressed. Palaima then concluded by saying that these tablets contain what in modern days would be labeled as legal nuances.

Hittites and Ahhiyawa in Western Anatolia: Two Worlds face-to-face

Livio Warbinek, University of Florence[18]

Abstract

This paper presents an overview of the relationship between the Aegean and the Anatolian civilizations during the Late Bronze Age and takes into consideration the complex topic defined as the “Ahhiyawa Question”. The aim is to show the problematic relations between the Ahhiyawa and Hittite people and to compare their worlds through the collection of the available sources. As it will be attempted to demonstrate, the dialogue between the two parties was seemingly impossible due to their different sense of self and others perception. This is why mutual relations face-to-face have never been consolidated as in other circumstances or contexts of the Ancient Near East.

§130. The Aegean world in the second half of the second millennium BCE was not limited to Mycenaean maritime domains, but also had intense relations with the Ancient Near East, primarily through the Anatolian coast (Cultraro 2006:201–211). On the other hand, the Hittite kingdom, during its long conquest of western Anatolia, came into contact with the Aegean world defined through the term Ahhiyawa, whose identification with the Αχαίϝοι-Mycenaeans is accepted here (Steiner 1998:169; Steiner 2010:591; Beckman et al. 2011:3–4; Egetmeyer 2022:1–2,9,12; Giusfredi 2022:II).

§131. The ongoing debate on the so-called “Ahhiyawa Question” originates from the studies of Forrer (1924a; 1924b), who first proposed the Ahhiyawa-Mycenaeans correspondence, and the subsequent publication of Sommer (1932), through which the scholar distanced himself from Forrer’s thesis by deeming Ahhiyawa an Anatolian state. After these two milestones in Hittite scholarship, scholars from both Hittitology and Classical studies have produced countless studies on the issue. The most recent and comprehensive contributions to this field of research are due to Fischer (2010) and Beckman et al. (2011). As for now, the identification of Ahhiyawa with the Mycenaean world is generally accepted, the debate remains open about the geographical location of the Ahhiyawa “kingdom” (Güterbock 1984:114–115; Freu 1990; Ünal 1991; Cultraro 2006:209; Giusfredi 2022:IV–V). The latter issue divides proponents of recognizing that country with one or more Mycenaean kingdoms on the Greek continent (Cline 1996:145; Beckman et al. 2011:3–4; Gander 2012:281–282), from those who prefer to locate the Ahhiyawa core on the Aegean islands, particularly Rhodes or Chios (Hawkins 1998:30; Mountjoy 1998:48–53; Egetmeyer 2022:17–18,28) or even in western Anatolia (Steiner 1998:170; Steiner 2010:600–608). The most recent studies show, however, that the geographical issue should be subordinated to the ethno-linguistic and socio-anthropological ones (Yakubovich 2010:79; Marazzi 2018:264–268).

§132. The available Hittite sources have retained an interesting collection of geographical names related to western Anatolia in the Late Bronze Age. The Hittite language, the most ancient Indo-European language attested so far, was recorded in cuneiform script composed of syllabic and logographic signs with a large use of determiners before or after a word. Among the various determinatives at disposal, some like URU “city” and KUR “land” served precisely to define geographical names. Therefore, the collection of Hittite geographical names is easier than locating them on the map. During the scholars’ attempt to reconstruct the Late Bronze Age Anatolian geography, some toponyms have aroused interest because of their assonance with names of Greek/Aegean origin (Assuwa/Asia, Apasa/Ephesus, Millawanda/Miletus, Wilusa/Ilios, Taruisa/Troy, Lazpa/Lesbos etc.). Those names recorded in the Hittite cuneiform texts piqued the interest of the first scholars to address the Ahhiyawa Question. The main problem related to the comparison of those toponyms concerns the different writing system: syllabic cuneiform vs. alphabetic script. The discussion involves also linguistics in relation to the several writing traditions in the same linguistic area which has an impact on the different vocalization of the related languages (Cotticelli Kurras and Giusfredi 2018:178–182; Giusfredi 2022:VIII–X; Egetmeyer 2022:3–6). Nevertheless, I would still consider the view expressed by Güterbock to be valid: “But I want to say that […] Common sense tells me that Hittites must have known the Mycenaeans, and that what they say about Ahhiyawa fits the picture if that name refers to them. I am not worried about the alleged linguistic difficulties: I do not think that phonetic laws apply to foreign names.” (Güterbock 1983:137).

§133. Having introduced the issue and related problems, it is necessary to indicate and identify sources that allow for a general historical analysis. The materials available to us in this regard are of two kinds: philological and archaeological. From a textual point of view, the available sources are all, or almost all, of Hittite provenance and report the toponym Ahhiyawa and the political role played by this kingdom in the affairs of western Anatolia. Indeed, these are those texts edited by Sommer (1932) and republished by Beckman et al. (2011). From a philological point of view, the Mycenaeans do not appear in the archives of the ancient Near East, thus delineating an apparent diplomatic absence of the “Achaeans” from the eastern political context (Bryce 2003:65; Waal 2019:24). From an archaeological point of view, however, the sources of interest to the Ahhiyawa Question concern the various archaeological findings, which can be divided into two macro-areas: a first central area comprising the Aegean and the coasts of western Anatolia, and a second peripheral comprising the Anatolian core under Hittite control. Concerning the first area, Mycenaean ceramics can be traced as early as LH I-II on the islands of Chios, Lemnos and Lesbos, and at Troy VI, probably the effect of trade, which increased during LH IIB, probably turned toward northern Anatolia along the Dardanelles route, establishing trade negotiations with the Hittites themselves (Cultraro 2006:206–207). The Mycenaean presence in western Anatolia during the Late Bronze Age became increasingly widespread; it is then plausible that the routes of Mycenaean merchants interested the areas of the Classical Lycia, Pamphylia and Cilicia, through an intermediate port of call at Ura, as a “sorting” area for goods to the Anatolian plateau and the island of Cyprus itself to the Syro-Palestinian coast (Jasink 2001; Bryce 2003:59–63). However, we have no Mycenaean archaeological findings in the Hittite hinterland, except for a few pieces of evidence.

§134. The first unique and interesting item is a fragment of incised local vessel from the Hittite capital Hattusa: it depicts a warrior who is somewhat different from the Hittite canon and who is significantly closer to representations of Mycenaean warriors (Waal 2019:25). Another case is the so-called “Walwaziti’s spearhead” (Bilgi 1989), which is a bronze spearhead with a slotted cannon graft, a characteristic that is typical of the Aegean environment and not of the Anatolian one where instead the points had a flat graft (as in the case of the so-called “dagger” of Anitta, see Özgüç 1956). However, what makes this product peculiar is the presence of an inscription in Anatolian hieroglyphic script (of the size of about 2 cm2) containing the following Anatolian hieroglyphic signs: LEO.VIR.ZI/A MAGNUS.SCRIBA “Walwaziti, Great Scribe” (Bilgi 1989). Therefore, the spearhead should be interpreted as a luxury good coming from the west, on which Walwaziti inscribed a “ownership mark” in consideration of it as a prestigious commodity. A similar case is the sword of Tuthaliya, one of the most important findings in Hittite Anatolia (Salvini and Vagnetti 1994; Cline 1996:137–140). In the summer of 1991, 750m away from the “Lion’s Gate” in the Hittite capital, a sword was found ten centimeters deep. The discovery occurred by chance during periodic road maintenance works and was perceived from the outset as extraordinary, since no similar objects have ever been found in central and eastern Anatolia. The sword, conserved today at the Çorum Museum, is made of bronze and was immediately striking both for the length of its blade (0.79 cm) and for the presence of an inscription in cuneiform script engraved along the blade. It reports in Akkadian language: “When Tuthaliya, Great King, has conquered the land of Assuwa, he dedicated these swords to the Storm-god, his Lord-protector” (Salvini and Vagnetti 1994:226–228). Such an inscription clearly informs us about the fate of this sword, which was dedicated by king Tuthaliya to the main god of the Hittite pantheon to thank him for the victory he achieved. From this information it has been argued that the king in question was that Tuthaliya I/II whose annals have come down to us referring to a series of military campaigns conducted against the “country of Assuwa” in western Anatolia, which rebelled against Hittite control (Salvini and Vagnetti 1994:228–232; Cline 1996:140–144). Two elements confirm that such a sword is not of Hittite manufacture but came from a spoil of war (Cline 1996:138). First, the Aegean typology: we are dealing with a sword of clear Aegean derivation, often generically referred to in archaeology as Cut & Trust because of the peculiarities of this type of weapon of having both a sharp blade and a pointed top. More specifically, it was juxtaposed with the type of swords classified as “B Swords” (Sanders 1961:22–25; Ünal 1999) mostly from the Greek continent and especially from Mycenae (Salvini and Vagnetti 1994:216–226; Cline 1996:139). Second, the particular plural term GÍR.HI.A used in the sword inscription should be translated as “daggers”, thus suggesting probably a case of ritual dedication in a sacred pit of weapons taken from enemies – knives or daggers mostly – including even a sword (Salvini and Vagnetti 1994:228).