2025.03.31, rewritten from 2022.06.19, rewritten from 2021.08.09 | By Gregory Nagy

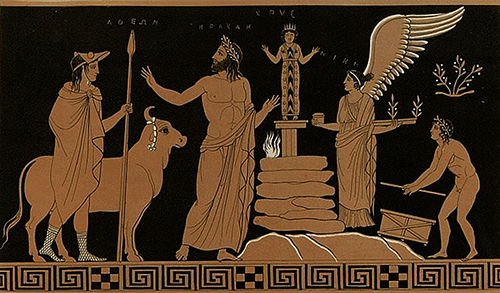

§0. The featured image for this essay is a drawing, made in the early nineteenth century of our era, which copies with some clarity and flair a picture painted on a vase manufactured in Athens in the fifth century BCE and now housed in Vienna. A follow-up illustration, immediately below the drawing, is a photograph of this ancient painting, and further below is an overall photograph of the vase itself. What we see pictured here is a scene derived from myths about the hero Philoctetes. We see him participating in a sacrifice that took place on an island named Chryse, sacred to a goddess named Chryse, whose cult statue, viewed frontally, is overseeing the sacrifice. This scene will be unfamiliar to readers who are familiar only with the version of the myth of Philoctetes that we see foregrounded by Sophocles in his tragedy named after this hero, Philoctetes, the première of which took place in 411 BCE at the festival of the City Dionysia in Athens. Before I focus on what will be unfamiliar, however, I review here what will seem quite familiar. In the version of Sophocles, as in the version of the myth we see in the picture I show here, Philoctetes is participating in a sacrifice. According to the letterings that label the characters involved in this picture, the sacrifice took place on the island Chryse, sacred to the goddess Chryse. In the version of Sophocles, however, unlike the version we see pictured here, the sacrifice went wrong. A snake guarding the cult statue of the goddess bit Philoctetes in the foot. This toxic wounding of the hero was a primal event to be hauntingly remembered in the tragedy created by Sophocles. But here is where things get unfamiliar, as we take a second look at what we see painted on the vase now housed in Vienna: there is no snake to be seen here. So, the sacrifice that is pictured in this painting is not marred by a traumatic snakebite. In fact, there cannot be any snakebite here, since the sacrifice that is pictured in this painting is not the same as the sacrifice pictured in the tragedy by Sophocles. The occasion for the sacrifice pictured in the painting, as we will see in what follows, was a prelude to a “First” Trojan War, whereas the occasion for the sacrifice pictured retrospectively in the tragedy of Sophocles was a prelude to the “Second” Trojan War as narrated in the Homeric Iliad. If we take into account all the surviving versions of myths about Philoctetes, we find that this hero visited the sacred island of Chryse two different times, participating in two different sacrifices. Despite, however, such a pattern of divergence to be noted in the surviving myths, we must also note a most salient point of convergence in the attested versions of these same myths about the two visits of Philoctetes to Chryse. The point of convergence has to do with the visualization of the cult statue that is sacred to the goddess Chryse. How this statue is pictured reveals glimpses, as I call them, of different traditions in the formation of myths that told about the two visits of Philoctetes to the sacred island of the goddess.

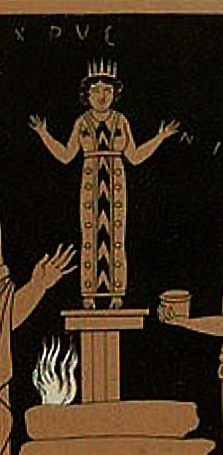

§1. In the picture I have just shown, to which I will hereafter refer short-hand as “Vienna 1144,” we see the goddess Chryse, visualized as a cult statue, presiding over the sacrifice of a bovine victim. Now I show a close-up of this same goddess in the same picture, where the goddess is clearly identified as Chryse by way of the Greek lettering above her head (ΧΡΥΣΕ).

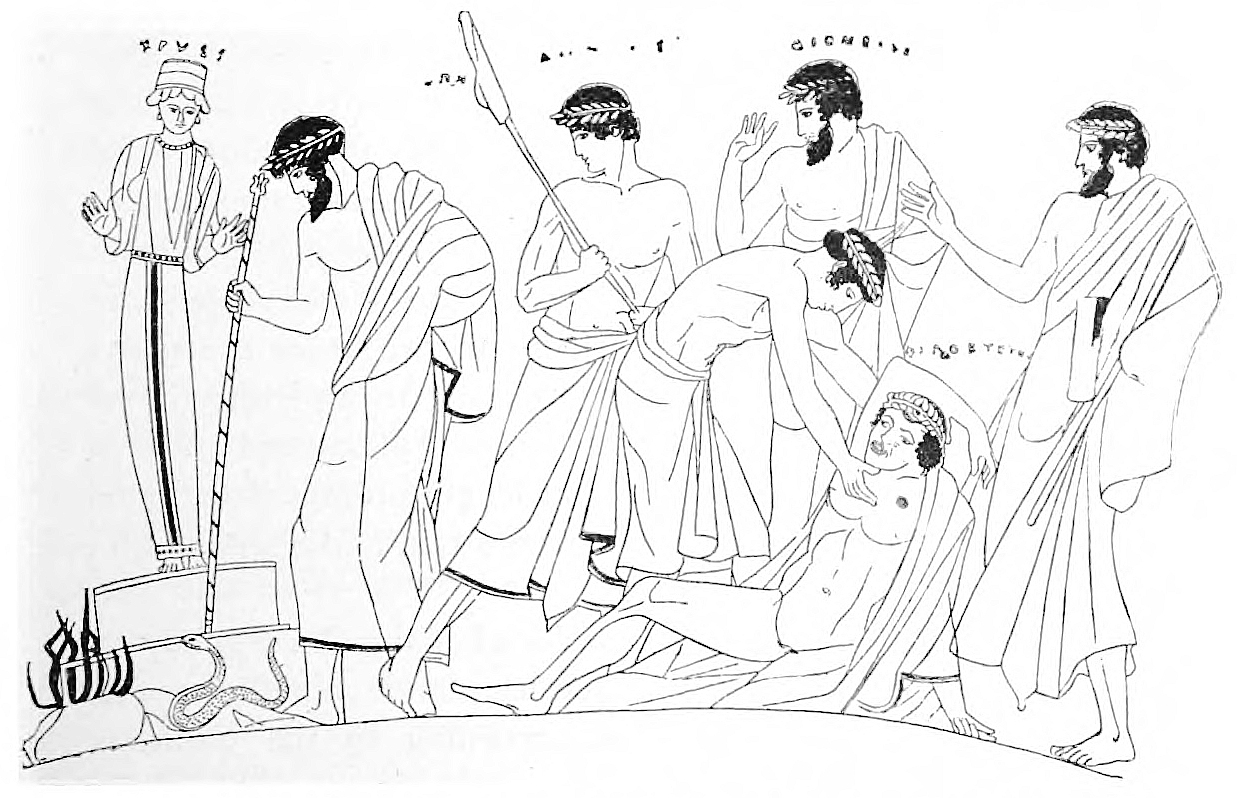

§2. But now I turn to another picture, painted on another vase. I now show here a drawing based on that picture, which derives, as I indicate in the caption shown below the drawing, from a painting on a vase housed in Paris, at the Louvre:

This drawing was featured, as I note in the caption, in Richard Jebb’s edition (1898) of the Philoctetes of Sophocles, with commentary, and the commentator adds his own interpretation of what we see being pictured in the original vase painting (Jebb p. 204):

The image of Chrysè stands in the open air on a low pedestal; just in front of it is a low and rude altar, with fire burning on it; close to this is the serpent, at which Agamemnon is striking with his sceptre, while the wounded Philoctetes lies on the ground, with Achilles and others around him.

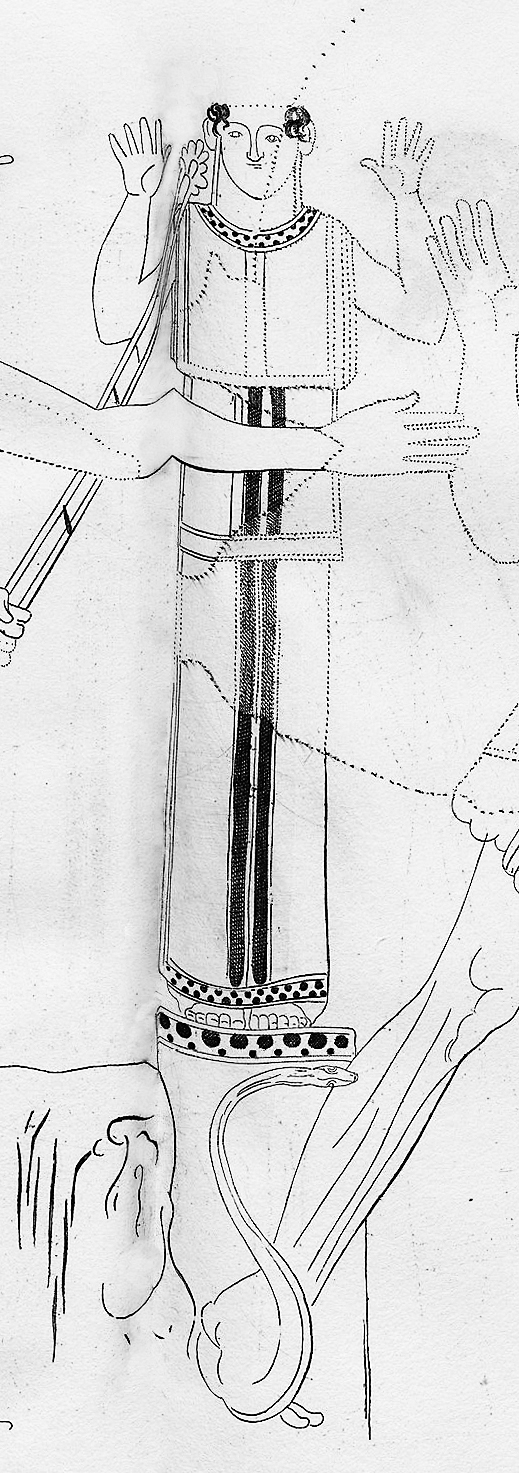

§3. Jebb’s comment here duly takes note of the goddess Chryse (he spells her name Chrysè), whose cult statue is seen on our left, far to the left—and whose identity is made clear by the Greek lettering above her head (ΧΡΥΣΕ). The fire that is blazing next to her altar signals that a sacrifice to her has been attempted, but the snake next to the fire signals that the sacrifice has failed, and that Philoctetes, whose open mouth signals his cries of pain, excruciating pain, has already been bitten by the serpent. The presence of the heroes Agamemnon and Achilles at this scene, both of whom are labeled by adjacent lettering, indicates that this attempted sacrifice to Chryse is a prelude to the Trojan War as narrated in the Homeric Iliad. And the wording of Sophocles in his Philoctetes actually refers to this goddess Chryse by name (lines 194 and 1327)—and to her island by the same name, Chryse (line 270). But there is a detail that is missing in the tragedy of Sophocles—a detail that is prominently displayed in the corresponding picture, Louvre G 143. That detail is the explicit visualization of Chryse as a cult statue. And I show here another such visualization, as painted on another vase that is housed at the Louvre. What we now see is a close-up from a line drawing, juxtaposed with a photograph of the actually attested fragments of the painting, to which I will refer hereafter as Louvre G 342:

§4. We have a problem here. The presence of a cult statue of Chryse in the two Louvre vase paintings G 143 and G 342, even though both these paintings are dated to the late fifth century BCE—perhaps late enough to postdate the relatively late première, in 411 BCE, of the tragedy Philoctetes by Sophocles—cannot be reconciled with the absence of any mention of such a statue in this tragedy. So, Sophocles cannot be the “source,” as it were, for visualizations of this cult statue in vase paintings.

§5. Such visualizations must have come from elsewhere. And the most plausible “source,” in the verbal arts, would have been a much earlier tragedy, the Philoctetes of Euripides, the première of which took place in 431 BCE (the information comes from “Argumentum 2” in the manuscript tradition for the Medea of Euripides, the première of which took place on the same occasion). A scenario for such a “source,” dated two decades before the première of the Sophoclean Philoctetes, has been offered by the noted art historian Edna M. Hooker (1950), and I quote here her formulation (p. 41): “It is quite likely that in the course of this play [by Euripides] Philoktetes described how, as a boy, he accompanied Herakles to the sanctuary of Chryse and how he subsequently visited it on his way to the Trojan War and was bitten by the snake; and it is possible that a vivid description was given of the sanctuary with its ancient altar and image.”

§6. In terms of this formulation, there were two visits by Philoctetes to the sacred island of Chryse. The myth about the second visit is of course well known, since it was foundational for the plot of the tragedy by Sophocles. But the myth about the first visit is hardly mentioned anywhere in ancient Greek texts that have survived to this day. I summarize here the essentials, derived mostly from three of the rare textual references to this myth (Philostratus Images 17.2; scholia for Sophocles Philoctetes 194; also “Argumentum 1” in the textual tradition of the drama). We learn from such textual sources that Herakles, before he engaged in the “First” Trojan War, sailed to the island of Chryse, together with heroes like the youthful Philoctetes, and, hoping for victory in the war, he sacrificed there to the goddess of the island. I should add that, even though the myth about this first visit is hardly known, it is connected with a set of very well-known myths about this “First” Trojan War, led by Herakles, as distinct from the “Second” Trojan War, led by Agamemnon. I have commented elsewhere on the pairing of these myths about the “First” and the “Second” Trojan Wars as depicted respectively in the sculptures of the East and West Pediments of the temple of “Aphaia” in Aegina, stemming from the early fifth century BCE (Nagy 2016.03.24 §14).

§7. The myth about the first visit of Philoctetes to Chryse, in the entourage of Herakles, who performed there a sacrifice of a bovine victim in hopes of achieving victory in the upcoming “First” Trojan War, is precisely what we see being pictured in “Vienna 1144”—to use again my short-hand way of referring to that painting. In “Vienna 1144,” as we look again at the drawing that I used as the cover illustration for this essay, we can see clearly that even the divine embodiment of victory, labeled as such, Nīkē, by the adjacent lettering (ΝΙΚΕ), is attending the sacrifice, standing next to the altar and assisting the chief sacrificer, Herakles, who is also assisted by the youthful heroes Iolaos and Philoctetes. I agree here with Edna Hooker (1950:37, 39), whose analysis makes it clear that not only Herakles but also Iolaos can surely be identified by the adjacent Greek letterings, barely visible in the painting, while the boy who is shown in the act of opening a casket—we see him at our right, far right—can just as surely be identified as Philoctetes. In the case of Philoctetes here, we find no adjacent lettering attached to the picture of the boy in “Vienna 1144,” but there is another painting, “London E 494,” dated as early as 430 BCE, which clearly shows the youthful Philoctetes, identified as such by adjacent Greek lettering (ΦΙΛΟ⟨Σ⟩ΚΕΤ[…]), and we see him here in the act of roasting sacrificial meat on a double spit, participating in a sacrifice at the altar of the cult statue of Chryse—a sacrifice attended by Herakles together with Philoctetes and with a second youth named Likhas (identified as ΛΙ[…]: Hooker p. 37). The youthful Likhas is also shown in another related painting that dates from the fifth century BCE, “Hermitage 43F,” where he is accompanied by another youth, who is most likely Philoctetes, in helping Herakles sacrifice a bovine victim to Chryse (Hooker p. 40). I mention here yet another painting that pictures the sacrifice, this one painted on a vase housed in Taranto (Museo Nazionale 52399; Hooker p. 35), where we see a closed casket placed directly in front of the altar of Chryse. This casket, as I will suggest in a few minutes, can be connected with the casket that we see being opened by the boy identified as Philoctetes in “Vienna 1144.”

§8. This review of surviving evidence from the visual art of vase painting shows that the cult statue of Chryse was in fact an integral part of the myth about the first visit of Philoctetes to the sacred island of Chryse. So, I agree with the analysis, as I have summarized it, by Edna Hooker (1950:41), where she traces this myth back to the Philoctetes of Euripides, on the basis of what we see in the relevant vase paintings. But can we say that this drama of Euripides, which goes back to 431 BCE, was really the “source” of the myth? I use the word “source” here in a qualified way, within “scare quotes,” since, as I argue in the next essay, I think there is no need to treat as “original” the Euripidean treatment of the myth.

§9. Before launching into the next essay, however, I must note that I cannot bring the present essay to a close without asking an open-ended question—about the presence of Chryse as a goddess presiding over an altar guarded by a snake. My question, which I cannot yet answer, has to do with the casket that we see being opened by the boy identified as Philoctetes in the first vase painting that I showed in this essay. Here, then is the question: was there something inside the casket that was being opened? In another vase painting that I have also already noted, we see another such casket—this one is closed shut—and it has been placed at the base of the altar sacred to Chryse. When he visited the sanctuary of Chryse the first time, in the entourage of Herakles, Philoctetes perhaps opened a casket containing a snake, releasing it to guard the sacred ground of the goddess—to guard it from future would-be sacrificers whose motives were unholy. And perhaps, when Philoctetes visited the same sanctuary of Chryse the second time, now in the entourage of Agamemnon, something went wrong, very wrong this time. When he set foot on the sacred ground of the goddess, Philoctetes was now bitten by the snake—a snake he may have once upon a time released from its casket to guard against sacrificers who dare to approach the goddess with unholy motives.

Bibliography

Alroth, B. [1992] 2013. “Changing Modes in the Representation of Cult Images.” In The Iconography of Greek Cult in the Archaic and Classical Periods, ed. R. Hägg. Liège. Open-access: https://books.openedition.org/pulg/185.

Heinrich, K. B. 1839. De Chryse insula et dea in Philoctete Sophoclis. Bonn.

Hooker, E. M. 1950. “The Sanctuary and Altar of Chryse in Attic Red-Figure Vase-Paintings of the Late Fifth and Early Fourth Centuries B. C.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 70:35-41.

Jebb, R. C., ed. 1898. Philoctetes. Cambridge.

Nagy, G. 2016.03.24. “Things noted during five days of travel study in Greece, 2016.03.13–18.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/things-noted-during-five-days-of-travel-study-2016-03-13-18/.

Nagy, G. 2016.10.08. “Sappho and mythmaking in the context of an Aeolian-Ionian Sprachbund.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/sappho-and-mythmaking-in-the-context-of-an-aeolian-ionian-poetic-sprachbund/.

Nagy, G. 2019. “A ritualized rethinking of what it meant to be ‘European’ for ancient Greeks of the post-heroic age: evidence from the Heroikos of Philostratus.” In Thinking the Greeks: A Volume in Honour of James M. Redfield, ed. B. M. King and L. Doherty, 173–187. London and New York. https://chs.harvard.edu/curated-article/gregory-nagy-a-ritualized-rethinking-of-what-it-meant-to-be-european-for-ancient-greeks-of-the-post-heroic-age-evidence-from-the-heroikos-of-philostratus/.

Nagy, G. 2021.02.20. “About Euripides the anthropologist, and how he reads the troubled thoughts of female initiands.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/euripides-the-anthropologist-and-his-imaginings-about-wandering-minds-of-female-initiands/.

Nagy, G. 2021.07.19. “Can Sappho be freed from receivership? Part One.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/can-sappho-be-freed-from-receivership-part-one/.

Nagy, G. 2021.07.26. “Can Sappho be freed from receivership? Part Two.” Classical Inquiries. https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/can-sappho-be-freed-from-receivership-part-two/.

Nagy, G. 2022. “Comments on the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey, by Gregory Nagy, restarted 2022.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/a-sampling-of-comments-on-the-homeric-iliad-and-odyssey-restarted-2022/.

Nagy, G. 2025.03.31. “Glimpses of two different myths about two different visits by Philoctetes to the sacred island of the goddess Chryse.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/glimpses-of-aeolian-traditions-in-two-different-myths-about-two-different-visits-by-philoctetes-to-the-sacred-island-of-the-goddess-chryse-2/.

Nagy, G. 2025.04.01. “Sappho’s Aphrodite, the goddess Chryse, and a primal ordeal suffered by Philoctetes.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/sapphos-aphrodite-the-goddess-chryse-and-a-primal-ordeal-suffered-by-philoctetes/.

Nagy, G. 2025.04.02. “How myths that connect the hero Philoctetes with the goddess Chryse are related to myths about a koúrē ‘girl’ named Chryseis in the Homeric Iliad.” Classical Continuum. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/how-myths-that-connect-the-hero-philoctetes-with-the-goddess-chryse-are-related-to-myths-about-a-koure-girl-named-chryseis-in-the-homeric-iliad/.

Pearson, A. C. 1889. The Fragments of Zeno and Cleanthes, with introduction and explanatory notes. Cambridge.

Tümpel, K. 1890. “Lesbiaka 2: Chryseïs-Apriate.” Philologus 49:89–120.