From Endings to Headings: Body Parts and Case Endings in Mycenaean Greek. Papers and Summary of the Discussion held at the Spring 2025 MASt Seminar (Friday, April 4)

§1. Rachele Pierini opened the Spring 2025 session of the MASt Seminar by welcoming the speakers Elena Džukeska and José Miguel Jiménez Delgado as well as the attendees of the April meeting.

§2. Elena Džukeska presented “Words for Objects and Parts of Objects Derived from Words for Body Parts: The Evidence of Mycenaean Greek.” In her work, Džukeska explored how words for body parts are used to denote objects or parts of objects in Mycenaean Greek. Through an analysis of the Linear B records, she investigated the semantic changes involved in this practice, its formation patterns, and its continued use in later Greek.

§3. In the second presentation, José Miguel Jiménez Delgado shared his thoughts on “Syncretism, Lenition of Inherited *s, and Linear B: A New Perspective on Dative Plural Endings in Mycenaean Greek.” In his talk, Jiménez Delgado focused on the Mycenaean Greek dative plural endings, particularly on their syncretism and the lenition of inherited *s.

§4. In addition to the MASt board members (Editor-in-Chief: Rachele Pierini; Associate Editor: Tom Palaima; Editorial committee members: Elena Džukeska, Joseph Maran, Leonard Muellner, Gregory Nagy, Marie Louise Nosch, Thomas Olander, Birgit Olsen, Helena Tomas, Agata Ulanowska, Roger Woodard; Secretary Coordinator: Giulia Muti; Secretary: Linda Rocchi; Editorial Assistants: Matilda Agdler, Harriet Cliffen, Diana Wolf, Katarzyna Żebrowska), roughly 75 attendees took part in the Spring 2025 MASt seminar, among whom Alcorac Alonso Deniz, Roberto Batisti, Stephen Colvin, Panagiotis Filos, Patricia García, David Goldstein, José Miguel Jiménez Delgado, Martin J. Kümmel, Georgios Kostopoulos, Hedvig Landenius Enegren, Olga Levaniouk, Chiara Mancini, Ester Salgarella, Kim Shelton, Sanja Smodlaka Vitas, Philippa Steele, Carlos Varias García, Brent Vine.

§5. Substantial discussions followed both presentations. Specifically, contributions to the seminar were made by Alcorac Alonso Deniz (see below at §§25; 63; 65—66; 68; 70), Elena Džukeska (§§15; 18; 20; 23; 26; 29; 32; 35; 72; 74), David Goldstein (§§45; 47; 49; 51; 53), José Miguel Jiménez Delgado (§§16—17; 19; 46; 48; 50; 52; 54—55; 57; 59; 61; 64; 67; 69; 71; 73; 75—76; 78; 80; 82), Hedvig Landenius Enegren (§§21; 24), Tom Palaima (§§12—14; 27—28; 30; 33—34; 36; 56; 58; 60; 62; 83), Rachele Pierini (§§22; 31), Carlos Varias García (§81), Brent Vine (§§77; 79).

Words for objects and parts of objects, derived from words for body parts: The evidence from Mycenaean Greek

Elena Džukeska

Introduction

§6.1. The practice of using words for body parts to denote objects or parts of objects is common in many languages. In Greek, it can be traced back to the Mycenaean period. For example, the word for ‘foot, leg’, πούς, refers to a human or animal limb, but it is also used to denote a table, bed, chair, or cauldron support, cf.

Α. τράπεζαν ἡμῖν ‹ἔκ›φερε τρεῖς πόδας ἔχουσαν, τέτταρας δὲ μὴ ‘χέτω.

Β. καὶ πόθεν ἐγὼ τρίπουν τράπεζαν λήψομαι;

(A) Bring us out a table with three legs; it mustn’t have four.

(B) And where am I to get a three-legged table?

Aristophanes Telemessians, fr. 545 (K.–A.III.2)

(transl. Henderson 2008)

In the Mycenaean Linear B records its basic meaning can be inferred from compounds such as τετράποδα ‘four-footed animals’, attested in instrumental plural, cf. qe-to-ro-po-pi (PY Ae 134 et al.), whereas its extended meaning is evident in a phrase like to-pe-za … e-re-pa-te-jo, po-pi (PY Ta 642.3b) ‘table … with legs made of ivory’.

§6.2. Furthermore, not only one, but multiple body part words can be systematically used to denote parts of the same object. For instance, in English, words like toe, foot, shoulder are used to describe in detail the design of a table leg, i.e. specific parts of the table leg. In Greek words like οὖς ‘ear’, πούς ‘foot, leg’, γάστρα ‘belly’ are used to indicate the handle, feet and lower part of a tripod cauldron. Cf.

γάστρην μὲν τρίποδος πῦρ ἄμφεπε, θέρμετο δ’ ὕδωρ·

Then the fire played about the belly of the cauldron, and the water grew warm.[1]

Homer Iliad, 18.348

δῶκε δ’ ἄγειν ἑτάροισιν ὑπερθύμοισι γυναῖκα

καὶ τρίποδ’ ὠτώεντα φέρειν· …

… and gave to his comrades, high of heart, the woman

and the eared tripod to bear away …

Homer Iliad, 23.512-513

Clearly, this is primarily a matter of semantic change, an extension of meaning. However, morphological processes can also be included, such as derivation with suffixes or compounding. For example, in English, the word hand itself has an extended meaning ‘hour and minute pointer on a watch’, but there are also words denoting objects derived from the word for hand with suffixes, such as hand-le ‘part of an object designed to be held in the hand when used’, and compounds like handbrake ‘a brake operated by hand’ or wash-hand-basin ‘a basin for washing the hands’. Similarly, in Greek, the word for ‘hand/arm’, χείρ has an extended meaning ‘kind of gauntlet, grappling iron’. From this word, χειρ-ίς ‘covering for the hand/arm’ is derived, and compounds like χειρο-λάβη (χείρ, λαβή) ‘handle’, or χειρό-νιπτρον (χείρ, νίζω/νίπτω, -τρο-) ‘basin/water for washing the hands’ are created.

§6.3. The purpose of this presentation is to discuss examples found in the Mycenaean Linear B records, highlighting some important aspects regarding the patterns of their formation and meaning, the continuity of their use in later Greek, and their significance as evidence for the history of the semantic relationship between words for body parts and words for objects in the Greek language.

Previous research and theoretical framework

§7.1. The etymology and morphological processes involved in the derivation of words for objects or parts of objects from body parts terms in the Greek language, including the Mycenaean period have been studied in detail from various perspectives. The semantic relationship between words for body parts and words for objects, on the other hand, has been the subject of inquiry mainly in cognitive linguistics studies dedicated to linguistic universals, embodiment, and conceptual metaphor.[2] The underlying theories in this research area are as follows: All languages have words for body parts, which often exhibit similar semantic extensions (Andersen 1978:352–353). Mental representations are based on the sensorimotor perception of the human body. Human thought processes are largely metaphorical. The metaphorization of body-part terms is one of the basic means of forming and expressing concepts in other domains (Lakoff and Johnson 1980:6; Pasch 2020:53–54; Kraska-Szlenk 2020:78–79).

§7.2. Regarding the domain of body parts, one of the topics discussed is the role of visually perceptible properties such as shape, size, or location as motivating factors for establishing nomenclature. Additionally, the polysemous relationship of terms referring to anatomically adjacent body parts (arm/hand, leg/foot, face/eye) has been explored (Andersen 1978:345, 354–359). In line with this, in his Dictionary of Selected Synonyms C. D. Buck argues that from the evidence of the Indo-European languages, it is demonstrable that so far as the etymology of inherited words for parts of the body is clear “the underlying notion is more often relating to the position or shape of the part than to its function.” Buck also notes that “there is frequent shift of application between words for parts of the body that are adjacent, of similar relative position, associated in function, or through common figurative uses with reference to the emotions.” (Buck 1949:197).

§7.3. Regarding the conceptualization of objects and their parts, the following regularities have been observed and discussed. Only those body parts that are perceptually salient tend to serve more frequently as source concepts. The underlying semantic relation, the metaphor AN OBJECT IS A HUMAN BODY, is based on establishing similarity in shape, size, relative position, and functionality between an object and a source body part. For instance, the leg is an elongated body part, which is why it serves as a source for the elongated part of the table, chair etc. (Kraska-Szlenk 2014:17, 31).

§7.4. The directionality of metaphorization has also been debated. It has been observed that the body parts domain can also be the target domain in the metaphorical process, with objects serving as conceptual sources (Pasch 2020:59; Tjuka 2024:385). In view of this, in a recent study, words for body parts and objects were analyzed in terms of three cognitive processes – similarity, contiguity, and part-of relations. These processes underlie body-object colexifications and reflect the semantic relations of metaphor, metonymy, and meronymy. It was observed that “it is crucial to consider body-object colexifications on a scale of literal versus figurative similarity.” (Tjuka 2024:381, 385–386, 412).

Mycenaean repertoire of words for body parts used in the domain of objects?

§8.1. Exploring the semantic relationship between words for body parts and objects in linguistic material from the Mycenaean archives may seem like an odd task. Human bodies were not of interest to Mycenaean scribes, and the only context in which body part terms only circumstantially refer to humans are the personal names.[3] However, scribes did record animals and objects, and it is in these specialized records that we find mentions of body parts. This along with the use of logograms, makes the Linear B tablets a very specific corpus. While, body parts can easily be related to objects, the administrative style of the scribes makes understanding their cognitive relations not always easy and straightforward.

§8.2. For the purpose of my analysis, I examined a number of Mycenaean forms that are presumably related to the following Greek words for body parts: πούς, ὁ ‘foot, leg’, σκέλος, τό ‘leg’, χείρ, ἡ ‘hand, arm’, ὦμος, ὁ ‘shoulder’, κάρα /κάρη, τό ‘head’, ὤψ, ἡ ‘eye, face’, οὖς, τό ‘ear’, ὀδούς (ὀδών), ὁ ‘tooth’, and ὄνυξ, ὁ ‘nail, claw’. All of these body part words have served as source concepts for objects in later Greek. I compared their metaphorical meanings in the domain of objects as attested on the Linear B tablets and in the later period of the Greek language. It should be noted that a more thorough analysis of this topic would likely need to include other Mycenaean words for objects related to body part terms as well.[4] Nevertheless, even a limited analysis reveals that the use of body part terms in the domain of objects spans a wide range of series and contexts (Knossos K, Od, L, Ln, Ld, Ws, V, Vs, So, Sd, Sg, Sk; Pylos Ta, Ub; Mycenae Wt, Ue series that deal with furniture, vessels, wheels, textiles, armour, horse equipment), confirming that the practice was common in Mycenaean Greek. As expected, in the alphabetic sources the evidence is even more abundant, including many other body part words and various objects.[5]

Patterns of formation and semantic change

§9.1. It seems that in the Mycenaean records there is evidence of the same patterns of formation that exist in later Greek and are also found in other languages: polysemy, extension of meaning without morphological changes, and morphologically more complex derivation with suffixes and through compounding. The extension of meaning can be inferred from the use of body part nouns in an appropriate context or indirectly from adjectives derived or compounded from the same stem or root. In the case of πούς, a word which is most frequently used in its metaphorical meaning and obviously denoting perceptually salient body part, all patterns are attested. As a noun πούς is attested in instrumental singular and plural, cf. po-de (PY Ta 641.1b), po-pi (PY Ta 642.3b). Items such as tables or portable hearths are described as being pe-de-we-sa (PY Ta 709.2b) ‘with feet/legs’ or we-pe-za (PY Ta 713.2) ‘with six feet/legs’ or e-ne-wo-pe-za (PY Ta 713.3) ‘with nine feet/legs’. A derivative with the suffix -ilo- from the ablaut grade πεδ– is πέδιλον ‘sandal, shoe’. On the Pylos tablet Ub(1) 1318 this word is attested in nominative plural, cf. pe-di-ra (r.3), genitive plural, cf. pe-di-ro (r. 5), and dative plural, cf. pe-di-ro-i (r. 7). Finally there are compound words with πούς, such as ti-ri-po, τρίπος ‘tripod cauldron’ or to-pe-za, τράπεζα ‘table’.

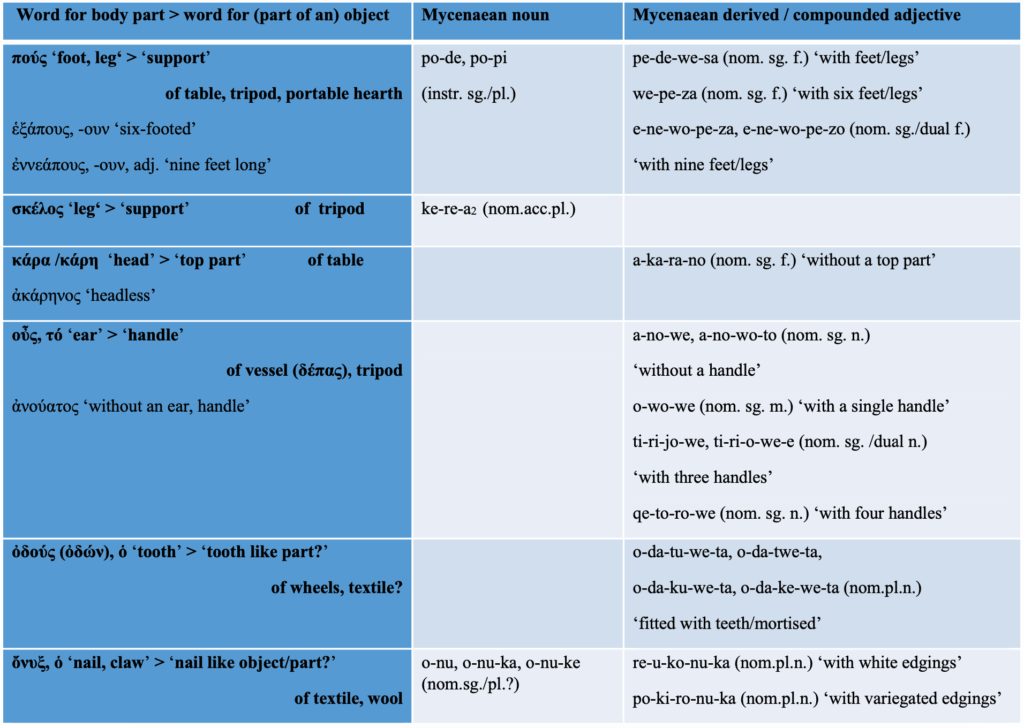

Table 1. Mycenaean words for body parts used in the domain of objects.

§9.2. Table 1 presents Mycenaean forms that testify to the polysemy of body part words, i.e., extension of meaning. As regards nouns, the case forms of πούς and σκέλος, instrumental singular and plural and accusative plural respectively are found in phrases describing tripods and a table, into which they seem to fit well syntactically and allow for interpretations such as ‘with a foot/feet/legs’ and ‘burned at the legs’.[6] Cf.

PY Ta 641.1b

ti-ri-po , e-me , po-de , o-wo-we *201VAS 1

“one tripod cauldron with a single foot and one handle”

PY Ta 642.3b

to-pe-za , ra-e-ja , a-pi-qo-to , ‘e-ne-wo , pe-za’ e-re-pa-te-jo, po-pi

“one stone table, a-pi-qo-to, with nine legs, with legs made of ivory”

PY Ta 641.1a-b

.1a , ke-re-a2 , *2̣0̣1̣VAS[

.1b ti-ri-po , ke-re-si-jo , we-ke , a-pu , ke-ka-u-me-ṇọ[

“one tripod of Cretan workmanship, burnt at the legs”

On the other hand, the forms of ὄνυξ are attested in elliptical constructions referring to logograms for textile and wool followed by numbers, which do not always align straightforwardly with the grammatical number.[7] Various solutions have been proposed: o-nu is considered of neuter gender, not masculine, with o-nu-ka corresponding as the nominative plural, and o-nu-ke as the dative singular form (Delgado 2016: 34–35); o-nu-ka is the scriptio plena of the nominative singular o-nu, and o-nu-ke is nominative plural (Meissner 2008:517); o-nu-ka is analyzed as a back formation on the compounded adjectives po-ki-ro-nu-ka ‘with variegated o-nu-ke’ and re-u-ko-nu-ka ‘with white o-nu-ke’ (Killen 1979:158). Alternatively, o-nu-k- has been interpreted as a stem of a root compound adjective meaning ‘stitched on, to be decorated with applications’, consisting of the first member ὀ- ‘on, to’, cf. ὀ-κέλλω ‘drive on, put to shore’, ὀ-τρύνω ‘stir up, encourage’, and second member νυχ–, cf. νύσσω ‘touch with a sharp point, prick, pierce’ (Leukart 1987:183–187). It can be added to this discussion that in order to understand better the morphosyntactic features of this noun and the elliptical constructions in which it is found, perhaps it could be compared with nouns such as θρίξ, τριχός ‘hair’ that is used in plural, and later collectively in singular or with θύσανος ‘tassel, fringe’ that is mainly used in plural.

§9.3. Regarding adjectives, their formation generally follows the patterns of the Greek language and features specific to the Mycenaean period. There are adjectives formed with the inherited Proto-Indo-European suffix -went-, such as nom. sing. fem. pe-de-we-sa, /pedwessa/ from the ablaut grade *ped- of πούς and the nom. plur. neutr. o-da-tu-we-ta/o-da-twe-ta and o-da-ku-we-ta/o-da-ke-we-ta, /odatwenta/ and /odakwenta/, variants from the alternative stems odat- (< *odn̥t-) and odak- (cf. adv. ὀδάξ ‘biting with the teeth’) of ὀδών.[8] Cf.

PY Ta 709.2b

e-ka-ra , a-pi-qo-to , pe-de-we-sa 1

“one portable hearth, a-pi-qo-to , equipped with feet”

KN So(1) 4440.b

.a de-do-me-na

.b a-mo-ta , / pte-re-wa , o-da-twe-ta ROTA ZE 6 [̣

“wheels, of elm-wood, fitted with teeth/mortised, delivered, WHEELS six pairs”

KN So(2) 4446

.1 a-mo-ṭạ[ / e-]ri-ka , o-da-ke-we-ta ROTA ZE 6̣2̣[ ] MO ROTA[ 1

“wheels, of willow-wood, fitted with teeth/mortised, WHEELS sixty-two pairs single WHEELS [1”

§9.4. There are compound adjectives with the word for body part as the second member and the first member number,[9] such as ti-ri-jo-we/ti-ri-o-we-e, nom. sing. neutr. and dual /triyōwes/, /triōwehe/ ‘with three handles’ and qe-to-ro-we, nom. sing. neutr. /kwetrōwes/ ‘with four handles’, compounds with τρι-(τρεῖς) ‘three’ and κwετρο-(τέσσαρες) ‘four’ and οὖς. Adjective forms we-pe-za, nom. sing. fem. /(h)we(ḱ)spegya/ ‘with six feet/legs’ and e-ne-wo-pe-za, e-ne-wo-pe-zo, nom. fem. sing. and dual /en(n)ewopegya/, /en(n)ewopegyō/ ‘with nine feet/legs’ are compounds with ἕξ ‘six’ and ἐννέα ‘nine’ and πεδ– (πούς), loosely corresponding to later ἑξάπους, –ουν ‘six-footed’ and ἐννεάπους, –ουν, adj. ‘nine feet long’ and regarding its second member to forms like τράπεζα ‘table’ and ἀργυρόπεζα ‘silver footed’, epithet to Thetis, Aphrodite, Artemis. Another adjective in this category is probably o-wo-we, nom. sing. masc. /oiwōwēs/ ‘with a single handle’ a compound with οἶος ‘alone’ and οὖς.[10] Cf.

PY Ta 641.2

di-pa , me-wi-jo , qe-to-ro-we *202VAS 1

“one smaller δέπας vase with four handles”

PY Ta 641.3

di-pa , me-wi-jo , ti-ri-jo-we *202VAS 1

“one smaller δέπας vase with three handles”

PY Ta 713.2

to-pe-za , e-re-pa-te-ja , po-ro-e-ke , pi-ti-ro2-we-sa , we-pe-za , qe-qi-no-me-na , to-qi-de 1

“one ivory table, po-ro-e-ke , decorated with feather pattern, with six legs, carved with a spiral”

PY Ta 715.3

to-pe-zo , mi-ra2 , a-pi-qo-to , pu-ko-so , e-ke-e , e-ne-wo-pe-zo , to-qi-de-jo , a-ja-me-no , pa-ra-ku-we 2

“two tables of yew, a-pi-qo-to, with box-wood supports, with nine legs, decorated with spirals, inlaid with emerald”

§9.5. Other compound adjectives include formations with ἀ(ν)- (<*n̥-) such as a-no-we, /anōwes/ or a-no-wo-to, /anōwoton/ nom. sing. neutr. compounds with οὖς ‘without handles’, corresponding to later ἀνούατος ‘without an ear, handle’ and a-ka-ra-no, nom. sing. fem. /akarānos/, ἀκάρηνος ‘headless’, a compound with κάρα.[11] Cf.

PY Ta 641.3

di-pa , me-wi-jo , a-no-we *202VAS 1

“one smaller δέπας vase without handle”

KN K(1) 875.1-6

di-pa , a-no-wo-to

”δέπας vase without handle”

PY Ta 715.2

to-pe-za , a-ka-ra-no , e-re-pa-te-ja , a-pi-qo-to 1

“one ivory table without a top part, a-pi-qo-to”

Finally, re-u-ko-nu-ka, /leukō|ǒnukha/ and po-ki-ro-nu-ka, /poikilō|ǒnukha/ are nom. plur. neutr. forms of adjectives compounded from adjectives denoting color λευκός ‘white’, ποικίλος ‘many-colored, variegated’, and presumably ὄνυξ.[12]

§9.6. For our discussion it is important to note that all of these adjectives indicate possession and reflect a “part-of” relationship (body part > object part). Adjectives with the suffix -went- or the prefix an- simply indicate possession, whether the object has the specific part or not. Other compounded adjectives further specify the quantity, quality, or design of the specific part. The metaphorical meaning of these adjectives is closely related to the metaphorical meaning of the body part word involved in their formation. However, their precise applicability has sparked many questions, even when their metaphorical meaning is clear.

§9.7. In the case of πούς, σκέλος and οὖς, the metaphor seems to be based on the similarity in shape primarily. Πούς and σκέλος have elongated shapes and denote the elongated parts of an object, whereas οὖς has a rounded shape and denotes the handle of a vessel with a similar shape. However, the similarity in relative position should also be taken into consideration. In the case of πούς and σκέλος the function to provide support is also similar. In later Greek πούς and οὖς were used with the same metaphorical meaning as in Mycenaean, to denote support and handle of furniture and vessels. On the other hand, this was not the case with σκέλος. An important question is whether Mycenaean forms related to πούς exhibit the same polysemy that this word has in later Greek, in terms of referring to both the foot and the whole leg. Compound nouns like ti-ri-po, and to-pe-za, and adjective forms with πεδ– as a second member like pe-de-we-sa, we-pe-za, e-ne-wo-pe-za indicate that πούς was already polysemous in this regard in the Mycenaean period of the Greek language. However, its parallel use with σκέλος on the same tablet PY Ta 641 in reference to tripods could indicate a narrower meaning of πούς as ‘foot’. Such a distinction was perhaps necessary because the scribe was focused on pointing out the different shapes/lengths of the tripod’s legs, or perhaps because he wanted to specify which part of the leg his observations referred to.[13]

§9.8. Based on the similarity in position the meaning of the word κάρα ‘head’ in later Greek was expanded to include ‘top, edge, brim’, cf. Eubulus, Kybeutai 56 (K.–A.V) (according to Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae 471D)

ἄρτι μὲν μάλ’ ἀνδρικὴν

τῶν Θηρικλείων ὑπεραφρίζουσαν [παρα],

κωθωνοχειλῆ, ψηφοπεριβομβήτριαν,

μέλαιναν, εὐκύκλωτον, ὀξυπύνδακα,

στίλβουσαν, ἀνταυγοῦσαν, ἐκνενιμμένην,

κισσῶι κάρα βρύουσαν, ἐπικαλούμενοι

εἷλκον Διὸς σωτῆρος.

A moment ago they were draining a

muscular Thericleian with foam running over the top [corrupt]

and a brim like a Spartan flask, which rattles when a

pebble’s rolled around inside it,

and is black and round and pointed on the bottom,

and shines and gleams and has been carefully washed,

and is covered on top with ivy; and they were invoking

Zeus the Saviour.[14]

In the Mycenaean documents, the term κάρα likely refers to the upper flat part of a table, perhaps a detachable section of the top (Shelmerdine 2012:690; Pierini 2021:126–127, Petrakis 2023:129) or the detachable top itself. It has been argued recently that the tables mentioned in the Ta series are cradle tables used for slaughtering sacrificial animals, specifically designed to be used without the top part (Morton et al. 2023: 175–178).[15]

§9.9. The interpretation of the metaphorical meaning of ὀδούς and ὄνυξ is more complex. Regarding ὀδούς, in the Linear B records, in the context of wheels, it presumably refers to a part that allows the spokes to be mortised into the felloe (Ruijgh 1976:180–182; 1979:211–213; Crouwel 2024:804–805). The extension of the meaning of this word in later Greek is based on the similarity in the sharp shape; it denotes ‘prong, spike, teeth of a saw, of a comb’. This case could be the same in Mycenaean, but similarity in function is perhaps even more conceivable. Teeth-like tools bite the material, teeth-like elements in carpentry make or fit into the openings by hammering. It should be noted that the same metaphor is attested to in the Greek word γόμφος ‘peg, bolt, dowel, any bond, fastening’, which comes from the PIE root *ǵembh– ‘bite’ and corresponds to words meaning ‘tooth, cutting tooth’, and also ‘any object with a sharp shape, like gear, comb’ in other IE languages, cf. Skt. jámbha– , Alb. dhëmb, OCS zǫbъ, Latv. zùobs, Toh.A kam, ToB keme, OHG kamb ‘comb’, Bulg. zabec ‘sharp tooth-like part of an object’, Serb., Croat. zupčanik, Mac. zapčanik ‘gear’ < PIE *ǵombho– (see DELG s.v. and EDG s.v.). Cf. Homer, Odyssey 5.244–248:

εἴκοσι δ’ ἔκβαλε πάντα, πελέκκησεν δ’ ἄρα χαλκῷ,

ξέσσε δ’ ἐπισταμένως καὶ ἐπὶ στάθμην ἴθυνεν.

τόφρα δ’ ἔνεικε τέρετρα Καλυψώ, δῖα θεάων·

τέτρηνεν δ’ ἄρα πάντα καὶ ἥρμοσεν ἀλλήλοισιν,

γόμφοισιν δ’ ἄρα τήν γε καὶ ἁρμονίῃσιν ἄρασσεν.

Twenty trees in all did he fell, and trimmed them with the axe; that he cunningly smoothed them all and made them straight to the line. Meanwhile Calypso, the beautiful goddess, brought him augers; and he bored all the pieces and fitted them to one another, and with pegs and morticing’s did he hammer it together.

§9.10. As regards ὄνυξ, its meaning in post-Mycenaean Greek was also extended based on the similarity in the sharp shape to denote objects like ‘fluke of an anchor’, and based on the similarity in function to denote tools like ‘a tool for scraping, making incisions’. It has been proposed that in Mycenaean the noun and adjective forms re-u-ko-nu-ka and po-ki-ro-nu-ka refer to a finishing decoration applied additionally on the fabric, such as fringe, tassels or sim (Killen 1979:158–162, Meissner and Tribulato 2002:304), or that they refer to the heading band with the warp threads and to the edgings (Firth and Nosch 2002–2003:134–135, Nosch et al. 2010:345, 348). Both interpretations imply that the metaphorical meaning is based on similarity in position. It is interesting to observe the expressions attested in later literary works, in which the metaphorical meaning of ὄνυξ is ‘end, edge’ literally and figuratively, cf. Euripides, Cyclops, 158–159:

Ὀδυσσεύς: μῶν τὸν λάρυγγα διεκάναξέ σου καλῶς;

Σειληνός: ὥστ’ εἰς ἄκρους τοὺς ὄνυχας ἀφίκετο

Did it slip very sweetly down your throat?

Throat, man? – to my very toes! I feel ’em tingling.[16]

ᾗ Πολύκλειτος ὁ πλάστης εἶπεν χαλεπώτατον εἶναι τὸ ἔργον, ὅταν ἐν ὄνυχι ὁ πηλὸς γένηται·

… it is for this reason that the sculptor Polyclitus said that the work is hardest when the clay is at the nail.[17]

Plutarch Moralia 2.636c

Such a more figurative and metaphorical meaning could have already been developed in Mycenaean, possibly implied by the use of this word in the domain of textile production.

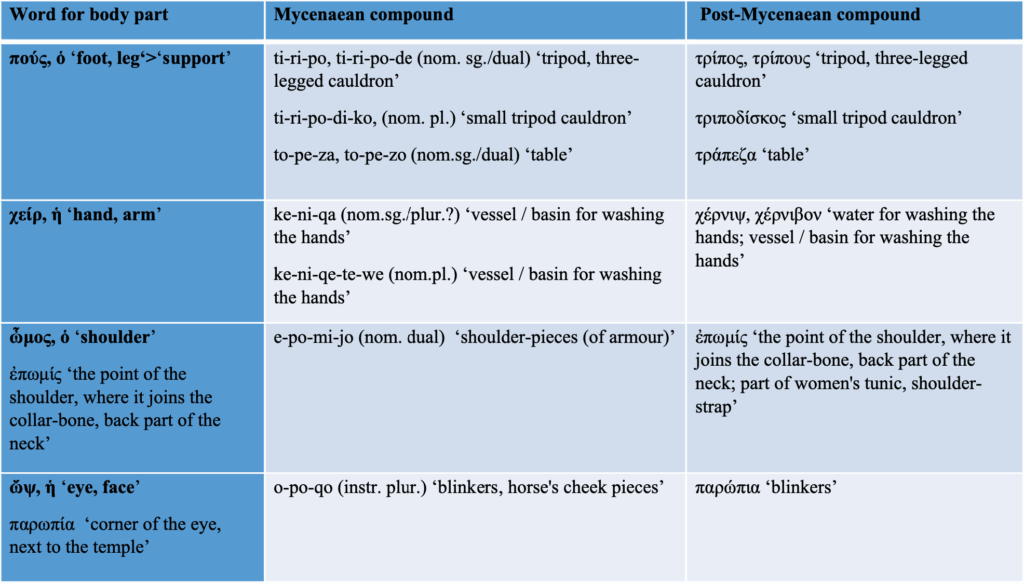

Table 2. Mycenaean compound words for objects derived from words for body parts

§9.11. In Table 2, Mycenaean words for objects that are compounded from words for body parts are presented. The words ti-ri-po, ti-ri-po-de, nom. sing. and dual. /tripos/, /tripode/, τρίπος, τρίπους ‘tripod’; ti-ri-po-di-ko, nom. plur. /tripodiskoi/, diminutive τριποδίσκος ‘small tripod cauldron’ and to-pe-za, to-pe-zo nom. sing. and dual /torpegya/, /torpegyō/, τράπεζα ‘table’ are compounds with πούς as the second member and the numbers three, τρι– (τρεῖς) and four τρ– < τετρα– (τέσσαρες) as first members. The relationship of the noun ‘tripod’ with the corresponding adjective τρίπους, –ουν ‘three-footed, three-legged, of three’ is obvious. The relationship of the noun ‘table’ with the adjective τετράπους, -ουν ‘four-footed’, cf. τετράποδα ‘four-footed animals’, Myc. instr. plur. qe-to-ro-po-pi, is disguised with phonological changes in the first member that have already taken place in Proto-Greek.[18] These words have been continually used throughout the history of the Greek language and have later served as a source for the conceptualization of other objects as well, τρίπους is used to denote ‘kind of earring’, ‘musical instrument’, while τράπεζα is used to denote ‘any flat surface, bench etc.’.

§9.12. Compounds with χερ– (χείρ) and the root of the verb νίζω/νίπτω ‘wash’ are Mycenaean forms ke-ni-qa (KN Ws 8497.β), nom. sing. scriptio plena for /khērnig(k)ws/, χέρνιψ used in reference to bath(s) a-sa-mi-to, /asaminthos/, ἀσάμινθος and ke-ni-qe-te-we (MY Wt 503), nom. plur. /khērnigwtēwes/, a noun in –ευς ‘hand-wash-basins’, cf. χειρόνιπτρον ‘hand-wash-basin’ (IG II.2/1427.col.II.24, Attica, fourth century BCE). In later Greek χέρνιψ means ‘water for washing the hands before meals’, cf. Homer, Odyssey 1.136–138:

χέρνιβα δ’ ἀμφίπολος προχόῳ ἐπέχευε φέρουσα

καλῇ χρυσείῃ, ὑπὲρ ἀργυρέοιο λέβητος,

νίψασθαι· παρὰ δὲ ξεστὴν ἐτάνυσσε τράπεζαν.

Then a handmaid brought water for the hands in a fair pitcher of gold, and poured it over a silver basin for them to wash, and beside them drew up a polished table.

On the Mycenaean tablets ke-ni-qa could also be interpreted as an adjective, but it is very probable that it is a noun meaning ‘vessel for pouring water/basin for washing the hands’. This meaning is supported by later Greek with the thematic form χέρνιβον, used alongside the athematic one, cf. ἔλαιον εἰς χέρνιβον (IG XI.2/144A.I.32, Delos, fourth century BCE).[19]

§9.13. On the Mycenaean tablets there are also prepositional compounds denoting objects, particularly parts of military equipment. In the Knossos Sk series, there is attested e-po-mi-jo, nom. dual /epōmiyō/ ‘shoulder-pieces (of armour)’, corresponding to the later Greek adjective ἐπώμιος, a compound with ἐπί and ὦμος, meaning ‘on the shoulders’ and a word for the body part ἐπωμίς ‘the point of the shoulder, where it joins the collar-bone, back part of the neck’, metaphorically ‘part of a women’s tunic, shoulder-strap’. In the Knossos Sd and Sf series, o-po-qo is found, instr. plur. /opōkwois/, a compound with ὀπί and ὤψ, meaning ‘blinkers, horse’s cheek pieces’, semantically corresponding to the later Greek body part term παρωπία, a compound with παρά and ὤψ, ‘corner of the eye, next to the temple’, metaphorically παρώπια ‘blinkers’.[20]

§9.14. The meaning of compound words for objects is primarily determined by the syntactical and logical relationship of its members and the aspect of centricity. These compounds typically highlight important aspects of the object. For instance, its function in the case of χέρνιβον, the number of feet/legs in possessive compounds like τρίπος or τράπεζα, and its relative position and function in prepositional compound such as παρώπια. However, to fully understand the semantics, we must also consider a metonymy based on contiguity, for example between the water used for washing hands and the vessel it is put in, or between any object with three or four legs and the specific one used for sitting or eating, the body part next the temple and its covering. Similarly, in the case of πέδιλον, the word is derived with the suffix -ilo- from πούς, highlighting the connection between the foot and its covering.

Conclusion

§10.1. There is no doubt that with the Linear B tablets, we have a unique opportunity to trace the history of words for parts of the body and objects within one language over a long-time span. It is striking to observe that the same principles of metaphorization (how similarity is established) and systematic conceptualization that we witness in our everyday lives were applied thousands of years ago. If we look at just one Mycenaean tablet, PY Ta 641 we will notice that the same object, the tripod, is described as having not only feet, but also legs and ears, just as in the alphabetic literary and epigraphic sources where it is described as having feet, ears and a belly. We will also notice that of these three parts, only one, πούς was essential enough to provide its name. It is also striking that the word tripod is still used today as the name of a three-legged stand for a camera or any other apparatus. The Mycenaean Linear B tablets probably testify to the same polysemy ‘foot/leg’ of this word that is attested in later Greek.

§10.2. Although the principles of metaphorization remain the same, the specific outcomes are generally more different than similar. The patterns of formation interchange, and the conceptualization takes different paths over time. Of the body part words that were analyzed for the purposes of this presentation, there is a continuity regarding the metaphorical meanings of only two words, πούς and οὖς. However, even in the case of these two words, there is a significant development. If the handle of a vessel was perceived as an ear in the Mycenaean period, later it was also associated with the act of taking or holding, and the word λαβή (λαμβάνω ‘take hold of, grasp, seize’), cf. also χειρολάβη (χείρ, λαβή) ‘handle’. The word πούς is used to denote other objects as well, such as the ‘lower corner of the sail or sheet, the rope fastened to the sail, by which the sail is tightened or slackened’ or ‘boundary stone’. The analysis also shows that the adjectives derived from the words for body parts attested in Mycenaean were preserved to a lesser degree. All of the compound words, on the other hand have exact or close parallels in the post-Mycenaean period of the Greek language.

§11. Bibliography

Andersen, E. 1978. “Lexical universals of body-part terminology.” In Universals of Human Language, ed. J. H. Greenberg, vol. 3 Word Structure: 335–368. Stanford.

Bernabé, A. 2016. “Testi relativi ad armi e armature.” In Manuale, 409–510.

Bernabé, A. and E. R. Luján. 2008. “Mycenaean Technology.” In Companion, 201–233.

Buck, C. D. 1949. A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages. Chicago and London.

Companion = Duhoux, Y. and A. Morpurgo Davies, ed. 2008. A Companion to Linear B: Mycenaean Greek Texts and Their World. Vol. 1. Bibliothèque des Cahiers de l’Institut de Linguistique de Louvain 120. Louvain.

Crouwel, J. 2024. “Finished Products II: Military Equipment. Part I: Archaeological Commentary.” In New Documents, 797–812.

DELG = Chantraine, P. 1968–1980. Dictionnaire étymologique de la langue grecque. Vols. I–IV2. Paris.

Delgado, J. M. J. 2016. Sintaxis del griego mycénico. Sevilla.

DMic. I = Aura Jorro, F. 1985. Diccionario micénico. Vol. 1. Madrid.

DMic. II = Aura Jorro, F. 1993. Diccionario micénico. Vol. 2. Madrid.

Duhoux, Y. 2008. “Mycenaean Anthology.” In Companion, 243–393.

EDG = Beekes, R. 2010. Etymological Dictionary of Greek. 2 vols. Leiden.

Firth, R. and M-L. Nosch. 2002-2003. “Scribe 103 and the Mycenaean Textile Industry at Knossos: The Lc(1) and Od(1) Sets.” Minos 37-38:121–142. https://dialnet.unirioja.es/servlet/articulo?codigo=2117613

Henderson, J. 2008. Aristophanes. Fragments. Loeb Classical Library 502. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

K.–A.III.2 = Kassel, R. and C. Austin, ed. 1984. Poetae Comici Graeci. Vol.III.2. Aristophanes. Testimonia et Fragmenta. Berolini et Novi Eboraci.

K.–A.V = Kassel, R. and C. Austin, ed. 1986. Poetae Comici Graeci. Vol.V. Damoxenus – Magnes. Berolini et Novi Eboraci.

Killen, J. T. 1979. “The Knossos Ld(1) Table.” In Colloquium Mycenaeum: actes du sixième Colloque international sur les textes mycéniens et égéens tenu à Chaumont sur Neuchâtel du 7 au 13 septembre 1975, ed. E. Risch and H. Mühlestein, 151–181. Recueil de travaux publiés par la Faculté des Lettres 36. Neuchâtel.

Killen, J. and J. Bennet. 2024. “Finished Products I: Vessels And Furniture.” In New Documents, 758–796. Cambridge. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/new-documents-in-mycenaean-greek/finished-products-i-vessels-and-furniture/3FD069269EBA785B37515E9470101A2F

Kraska-Szlenk, I. 2014. “Semantic extensions of body part terms: Common patterns and their interpretation.” Language Sciences 44:15–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langsci.2014.02.002.

Kraska-Szlenk, I. 2020. “Towards a semantic lexicon of body part terms.” In Body Part Terms in Conceptualization and Language Usage, ed. I. Kraska-Szlenk, 77–98. Amsterdam and Philadelphia.

Lakoff, G. and M. Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago and London.

Lejeune, M. 1971. Mémoires de philologie mycénienne. Rome.

Leukart, A. 1987. “Mycenaean o-nu-ka, o-nu-ke etc.: a concealed root-compound?” In Tractata mycenaea: Proceedings of the Eighth International Colloquium on Mycenaean Studies, held in Ohrid, 15-20 September 1985, ed. P. Hr. Ilievski and Lj. Crepajac, 179–187. Skopje.

Manuale = Del Freo, M. and M. Perna, ed. 2016. Manuale di epigrafia micenea. 2 vols. Padua.

Meissner, T. 2008. “Notes on Mycenaean Spelling.” In Colloquium Romanum. Atti del XII Colloquio internazionale di micenologia, Roma, 20-25 febbraio 2006, ed. A. Sacconi, M. Del Freo, L. Godart, M. Negri, 507-519. Pisa and Rome.

Meissner, T. and O. Tribulato. 2002. “Nominal composition in Mycenaean Greek.” TPhS 100(3):289–330.

Morton, J., N. G. Blackwell and K. W. Mahoney. 2023. “Sacrificial Ritual And The Palace Of Nestor: A Reanalysis Of The Ta Tablets.” AJA 127(2):167-187. DOI: 10.1086/723242 https://works.swarthmore.edu/fac-classics/85.

New Documents = Killen, J., ed. 2024. The New Documents in Mycenaean Greek. 2 vols. Cambridge.

Nosch, M.-L., M. Del Freo, and F. Rougemont. 2010. “The Terminology of Textiles in the Linear B Tablets, Including Some Considerations on Linear A Logograms and Abbreviations.” In Textile Terminologies in the Ancient Near East and Mediterranean from the Third to the First Millennia BC, Ancient Textiles, ed. M.-L. Nosch and C. Michel, 338–373. Series 8. Oxford.

Palaima, T. 2023. “The Pylos Ta Series and the Process of Inventorying Ritual Objects for a Funerary Banquet.” In Processions: Studies of Bronze Age Ritual and Ceremony presented to Robert B. Koehl, ed. J. Weingarten, C. F. Macdonald, J. Aruz, L. Fabian, and N. Kumar, 222–233. Oxford. https://sites.utexas.edu/scripts/files/2023/10/2023-TGP-The-Pylos-Ta-Series-and-the-Process-of-Inventorying-Ritual-Objects-for-a-Funerary-Banquet.pdf

Pasch, H. 2020. “Body-part terms as a linguistic topic and the relevance of body-parts as tools.” In Body Part Terms in Conceptualization and Language Usage, ed. I. Kraska-Szlenk, 53–75. Amsterdam and Philadelphia.

Petrakis, V. 2023. “‘Heads’ of thrones: once more on Mycenaean se-re-mo-ka-ra-a-pi and se-re-mo-ka-ra-o-re.” SMEA NS 9: 115–136.

Pierini, R. 2021. “Mycenaean wood: re-thinking the function of furniture in the Pylos Ta tablets within Bronze Age sacrificial practices.” In Thronos: historical grammar of furniture in Mycenaean and beyond, ed. R. Pierini, A. Bernabé, and M. Ercoles, 107–135. Eikasmos 32. Bologna.

Plath, R. and J. Killen. 2024. “Finished Products II: Military Equipment. Part II: The Texts.” In New Documents, 797–837. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/abs/new-documents-in-mycenaean-greek/finished-products-ii-military-equipment/CDE6ED86AEB4EAA3120BB54501687209

Risch, E. 1974. Wortbildung der homerischen Sprache. 2nd ed. Berlin and New York.

Ruijgh, C. J. 1976. “Chars et roues dans les tablettes mycéniennes: la méthode de la mycénologie.” In Mededelingen der Kon. Ned. Akademie van Wetenschappen 39:171-200. Amsterdam.

Ruijgh, C. J. 1979. “Faits linguistiques et données externes relatifs aux chars et aux roues.” In Colloquium Mycenaeum: actes du sixième Colloque international sur les textes mycéniens et égéens tenu à Chaumont sur Neuchâtel du 7 au 13 septembre 1975, ed. E. Risch and H. Mühlestein, 207–220. Recueil de travaux publiés par la Faculté des Lettres 36. Neuchâtel.

Russotti, A. 2021. “Ti-ri-po: unusual description for an every-day object.” In Thronos: historical grammar of furniture in Mycenaean and beyond, ed. R. Pierini, A. Bernabé, and M. Ercoles, 31–41. Eikasmos 32. Bologna.

Shelmerdine, C. 2012. “Mycenaean Furniture and Vessels: Text and Image.” In KOSMOS: Jewellery, Adornment and Textiles in the Aegean Bronze Age. Proceedings of the International Aegean Conference, University of Copenhagen, Danish National Research Foundation’s Centre for Textile Research, 21–26 April 2010, ed. M.-L. Nosch and R. Laffineur, 685–695. Aegaeum 33. Liège and Austin.

Speciale, M.S. 2000. “Furniture in Linear B: The Evidence for Tables.” In Πεπραγμένα του Η΄ Διεθνούς Κρητολογικού Συνεδρίου, Ηράκλειον 9-14 Σεπτ. 1996, ed. Α. Καρέστου, Θ. Δετοράκης and Α. Καλοκαιρινός, 227–239. Iraklion.

Tjuka, A. 2024. “Objects as human bodies: cross-linguistic colexifications between words for body parts and objects.” Linguistic Typology 28(3):379–418.

Varias, C. 2016. “Testi relativi a mobilio e vasi pregiati.” In Manuale, 551–565.

Waanders, F. M. J. 2008. An Analytic Study of Mycenaean Compounds. Structure. Types. Pisa and Rome.

Yasur-Landau, A. 2005. “Mycenaean, Hittite, and Mesopotamian Tables ‘with Nine Feet’.” SMEA 47:299–307.

Discussing Džukeska’s talk “Words for Objects and Parts of Objects Derived from Words for Body Parts”

§12. Tom Palaima complimented Džukeska’s presentation and reflected on Ta 641, the last tablet shown by Džukeska, and the linguistic issue concerning -po-de ‘foot’ and ke-re-a2 (= skelos) ‘leg’, which the tablet highlighted. Palaima mentioned that he teaches a course on Bob Dylan, which had led him to explore other popular singers, including Neil Young. Palaima cited a lyric from Young’s song Old Laughing Lady, in which a drunkard “can’t tell his ankle from the rest of his feet” to point out that this line is one of the few instances in English where the boundary between leg and foot is blurred, akin to the semantic extension seen in the Mycenaean terms under discussion. Palaima speculated that this could be a Canadian idiom but saw it as a poetic example of such anatomical conflation.

§13. Palaima then returned to skelos, reflecting on its Indo-European roots and comparing it to the root for ‘foot’, namely ped- and pod-, which links the foot with the ground. Palaima referenced the military expression “feet on the ground” to illustrate the persistent conceptual connection between feet and the earth, and pointed to a deep-rooted semantic relationship dating back to Indo-European origins.

§14. In addition, Palaima considered the example of the tripod mentioned in the tablet, where the term used implies the loss of a ‘leg’. He noted that the term might have referred to an upward extension rather than a foot and that pod-de could have been used instead if the reference had been to a foot specifically. This interpretation, Palaima observed, echoed Neil Young’s lyric in its implication that certain parts of the leg and foot can be indistinguishable.

§15. Elena Džukeska acknowledged Palaima’s points and emphasized that body parts are indeed significantly involved across many conceptual domains. Džukeska noted that while the domain of objects tends to be more literal in its references, the use of body parts in other domains—particularly metaphorical ones—is far more intriguing. These metaphorical applications, she highlighted, are also connected to the more literal usages. Furthermore, Džukeska remarked that metaphors involving body parts often overlap and intersect across different contexts, suggesting that the relationships are more complex than they might initially appear.

§16. José Miguel Jiménez Delgado praised Elena Džukeska’s presentation, noting that little could be added given the clarity of the talk but noted that Palaima’s earlier remarks had been particularly thought-provoking. Building on those points, Jiménez Delgado suggested that the term skelos might have been used deliberately to highlight the leg, whilst pous could have been employed metonymically to refer to both the leg and the foot.

§17. Jiménez Delgado then raised a question regarding possible parallels in first-millennium Greek, asking Džukeska whether such parallels could help clarify why the scribe chose to use two different terms in the same context.

§18. Džukeska agreed with Delgado’s observation, stating that it seemed evident the scribe intentionally chose two different terms to denote distinct elements. She suggested that the distinction was deliberate, as the scribe aimed to differentiate between the ‘foot’ and the entire ‘leg’ of the object in question. Referring to the imagery associated with the tablet, Džukeska noted that, as with furniture, a leg may also have a foot, and the two are not the same. She emphasized that the scribe likely intended to describe a situation where the entire leg of the object had been burned, and thus chose specific terminology to convey this nuance more precisely.

§19. Jiménez Delgado then asked for Džukeska’s opinion on the meaning of onyx ‘nail’ in Mycenaean. Specifically, he wondered whether within textile terminology the term referred to a decorative motif or a utensil, perhaps a tool related to weaving.

§20. Džukeska replied that she is not a textile specialist but an intuitive interpretation could be toward a functional rather than purely decorative understanding of the term. Džukeska suggested that onyx could potentially refer to both a decorative element, such as a tassel or a base. She explained that she had recently come across images of ancient warps, which resembled something akin to onyx, prompting her to consider this connection further. Džukeska highlighted that the term o-da-ku-we-ta (= odakwenta) had also appeared in textile contexts and noted the lack of clear explanations for such adjectival usage. She speculated whether odakwenta might function similarly to onyx, perhaps as an adjective that became synonymous with a specific textile element. Džukeska referred to interpretations proposing that the term related to something positioned at the edge or end of a textile, but she admitted that she had no definitive explanation. She added that in Japan, some artists shape their nails into comb-like forms to create warp threads in textiles. While they found this technique fascinating, Džukeska acknowledged uncertainty as to whether such practices would have any relevance to the Mycenaean weaving technologies.

§21. Landenius Enegren thanked Džukeska for her interesting and very clear presentation, particularly in relation to the terms based on onyx. She suggested that these terms primarily denote the extremities of a weave, rather than referring to a specific shape. Landenius Enegren noted that the comparison lies more in the concept of location, such as nails on hands or feet, than in form. In her view, the terms point to fringes, which appear to have been significant elements in textile production. Landenius Enegren added that the existence of specialized fringe makers further supports this interpretation.

§22. Pierini seconded Landenius Enegren and added that she too concludes that o-nu-ka refers to fringes and edgings in her latest paper (Pierini 2024:418). Here, she has analyzed compound adjectives like re-u-ko-nu-ka ‘white-edged’ and po-ki-ro-nu-ka ‘multicolour-edged’, both describing luxury textiles, possibly intended for elite individuals, and concluded that the contexts in which they appear support the interpretation of o-nu-ka as edgings or fringes. Also, she remarked that a distinction can be proposed between o-nu-ka (decorative edgings) and o-nu-ke (a structural heading band).

§23. Elena Džukeska noted the existence of the term kraspedon in later Greek, which refers to the edge of a cloth. Džukeska pointed out that if kraspedon is derived from the word for ‘head’, then it could reinforce the semantic pattern that links bodily extremities with textile edges. This, she highlighted, aligns with the broader idea of using body-related metaphors, such as nails or heads, to denote the margins or terminal elements of woven fabrics.

§24. Hedvig Landenius Enegren reflected on personal experience in southern Italy, where traditional weaving practices are still maintained. She noted that while every weaver is capable of making a fringe, there are specialists dedicated specifically to this task. Landenius Enegren added that this topic would be further explored in an upcoming paper that she will present at the colloquium in Madrid.

§25. Alcorac Alonso Deniz expressed appreciation for the presentation and raised a question regarding the word pa-ra-wa-jo. He noted that this term is related both to the ear and to a part of the human body, and might also serve as a metaphor for a specific part of the brittle. Alonso Deniz suggested that there could be a combination of metaphorical and positional meanings at play. He further proposed that pa-ra-wa-jo, meaning something near the ear, could also be used in a more literal sense, referring to something defined by its position rather than as a metaphor. This duality, he added, might offer a solution to the question at hand.

§26. Elena Džukeska agreed that the term pa-ra-wa-jo should be added to the list of relevant words, noting that παρειά could also refer to ‘cheeks’, making it another example of a body part in the same conceptual scheme. Džukeska explained that παρειά is a prepositional compound used to denote a body part, much like other terms in Greek that describe body parts or equipment for both humans and animals. She further discussed how cognitive linguists have established a hierarchy in body part terminology, with primary terms related to the head at the top of the hierarchy, followed by other body parts. Džukeska, then, highlighted that in Greek, such terms are often formed using prepositions, fitting into the second level of this hierarchy.

§27. Tom Palaima inquired whether speed afoot was described in the ancient Greek poetic tradition using phrases like πόδας ὠκύς for ‘swift in regard to feet’ for other animals, such as horses galloping or deer or dogs or boars running fast with their legs, as we see in frescoes and on seal images. That is, do the Greek oral and later poets ever anatomize how non-human animals generate their speed?

§28. Palaima raised a second point focusing on the emphasis on feet for swiftness and noting that in American sports terminology, there is a famous running back known as “Crazy Legs”. He highlighted how swiftness is often associated with the legs rather than the feet and pointed out that, like Achilles, who is notable for his swiftness in battle, the feet are typically the focal point of descriptions of speed. Palaima further noted that even in modern sports, the focus is often on the feet, citing the popularity of training shoes and that Hermes is often described as swift due to the wings on his feet rather than his legs. He concluded by asking Džukeska whether Greek poets might use terms like ὄνυξ ‘hoof’, accus. plur. ὄνυχας ‘hooves’, in describing the swiftness of horses’ hooves, given their interest in animal-related terminology.

§29. Džukeska replied by reflecting on the use of pous, which means both ‘foot’ and ‘leg’ in Greek. She noted that it is the most frequent word used for both feet and legs in Greek, unlike skelos, which is less frequent and may refer more specifically to the ‘leg’ or ‘extremity’. Džukeska suggested that skelos could be understood as referring to the general extremities of the body, possibly including both the hands and legs. In contrast, pous is more commonly used for both feet and legs, she observed. Džukeska concluded by expressing uncertainty as to whether the distinction between feet and legs could always be made clear in Greek compounds.

§30. Palaima continued that he would be more closely scouring the literature for discussions of the “quickness” of animals while moving across the earth, as the ZOIA Conference (Laffineur and Palaima 2021) and its theme of animal/human Interactions had made him intrigued by this topic.

§31. Rachele Pierini returned to the discussion on the perception of the objects which were named with words for human body parts. She enquired about Džukeska’s opinion on the degree of etymological awareness among Mycenaean speakers and scribal hands.

§32. Elena Džukeska stated that she believed there was a large degree of awareness of this connection, as the act of naming the cauldron foot after the body part in the first place–the process of adjectivizing and later nominalizing it in a compound—shows this connection to be salient and important in speakers’ minds. Further, Džukeska drew attention to a paper by Petrakis (2023), where he discusses this naming phenomenon from an archaeological perspective and highlights the anthropomorphic aspect of the practice. Džukeska argued that anthropomorphism was probably a dominant factor in this practice and that we should take this non-linguistic perspective into consideration as well.

§33. Tom Palaima added another perspective to the discussion by highlighting the role of pous ‘foot’ as the human’s most prominent and frequent contact point with the earth, exemplified by our walking around. Palaima added that this could explain the prominence of pous in naming objects, especially as the feet of a cauldron also acted as the points of contact with the dangerous fire during cooking. In this view, skélos ‘cauldron leg’ represents a marked and, Palaima remarked, very conscious choice in a-pu ke-ka-u-me-no ke-re-a2 (PY Ta 641), used to describe the whole legs having been burnt off and not only the feet (as pous would be ambiguous).

§34. Palaima also referenced an article by T.W. Allen (1907), who highlights the significance of the kindship bond and the fact that modern philologists have done it a disservice by de-accentuating this bond. Palaima likened this bond to the way in which Bob Dylan named Woody Guthrie his “musical father”, and the way Jack Elliott came to see Bob Dylan as his son. Accordingly, it is important to take into consideration and try to reflect upon how the ancient human actually felt about their feet, and what it meant to have two feet on the ground back then—Palaima concluded.

§35. Elena Džukeska agreed with the previous point, adding that she was uncertain about how the issue would appear from an archaeological perspective. She suggested that perhaps the tripod only acquired its specific function once it had feet, questioning whether it would even work on a fire without them.

§36. Palaima responded by asserting that without feet, the object was essentially just a cauldron. He explained that the addition of feet transformed it into a tripod, though in some cases the feet were minimal. Palaima described certain tripods with feet resembling those of a lamp, using a lamp nearby as a visual reference. In such instances, he noted, the feet were not especially prominent and primarily served as a base. However, he emphasized that if the object were to be used over a fire, more substantial feet—or a more pronounced skelos—would be necessary. Palaima praised again the paper presented and expressed his admiration and gratitude toward those who had made the session possible, including Rachele Pierini and the MASt editorial team (Giulia Muti, Katarzyna Żebrowska, Linda Rocchi, Matilda Adgler, Diana Wolf) as well as Greg Nagy, Leonard Muellner, and Roger Woodard. He reflected on how privileged he felt to attend such a talk on a Friday morning from the comfort of a remote location.

§37. Bibliography

Allen, T. W. 1907. “The Homeridae,” The Classical Quarterly 1:135–143.

Petrakis, V. 2023. “‘Heads’ of Thrones: Once More on Mycenaean se-re-mo-ka-ra-a-pi and se-re-mo-ka-ra-o-re,” Studi Micenei ed Egeo-Anatolici NS 9:115—136.

Pierini, R. 2024. “Colour-Coding Aegean Elites: Status and Cultural Identities in Linear B Dyed Textiles and Late Bronze Age Socio-Political Changes,” Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History 11:401—424.

Laffineur, R. and T.G. Palaima (eds). 2021. ZOIA. Animal-Human Interactions in the Aegean Middle and Late Bronze Age Proceedings of the 18th International Aegean Conference, originally to be held at the Program in Aegean Scripts and Prehistory, in the Department of Classics, the University of Texas at Austin, May 28-31, 2020, Leuven 2021.

Syncretism, lenition of inherited *s, and Linear B: a new perspective on dative plural endings in Mycenaean Greek

José Miguel Jiménez Delgado

Dative plural endings in Mycenaean Greek

§38.1. The Mycenaean dialect as we know it from the texts written in Linear B presents a considerable number of endings for expressing values related to the dative plural in ancient Greek. These endings are as follows:

–Ca-i, –Co-i, and –si, which express plural forms of the dative and the locative[21]

–Ca and –Co, which express the instrumental plural

§38.2. In addition to these endings, there is the adverbial morpheme –pi, which is added to the stem and can be combined with nouns of the first declension, thematic nouns, and nouns of the third declension to express the plural forms of the instrumental and the locative.

§38.3. Therefore, it follows that syncretism of the dative with the locative and the instrumental had not fully occurred. In this sense, the plural forms of the dative and the locative were already expressed with the same ending, while the first and second declensions would have specific endings for the instrumental plural, in addition to an adverbial suffix for the expression of the plural forms of the locative and the instrumental.

§38.4. Beyond these processes of syncretism still in fieri, the interpretation of these endings has given rise to some debate among mycenologists. The vast majority of them follow Ventris and Chadwick (1956:84–85) — Merlingen (1954:12) was the first to make this proposal — and interpret –Ca-i and –Co-i as continuations of the inherited locative plural endings (-āsi and –oi̯si) with aspiration of the intervocalic sibilant, while –Co would be a continuation of the inherited instrumental plural ending (-ōi̯s) and –Ca would have been created by analogy with it. This interpretation takes into account both the distribution of these endings in the available documentation (Lejeune 1968) and the Indo-European comparison since –pi would be very rarely found in the second declension, in the same way that, in Indo-Iranian, the instrumental plural of thematic nouns is formed with –āis instead of –bhis, although –ebhis < *-oi̯-bhis is also found in Vedic.

§38.5. Nonetheless, Ruijgh (1967:76–78, 82–83) — see also Ruijgh (1958; 1979:82–84) — posits it as probable that the process of syncretism is more advanced, given that both –Co-i, which would be the continuation of the inherited instrumental ending, and –Ca-i, which would have been created by analogy with the previous ending, would express the three values under consideration. In this sense, –Co and –Ca would be graphic variants of the previous endings. Brixhe (1992; 2006:51–52) and Moralejo (1992)[22] share the same opinion. Ruijgh puts forth two arguments. First, he posits that the sibilant of the old inherited inflection of the locative plural –si has already been restored, as evidenced by the i– and u-stems of the third declension[23] and the sigmatic aorist and future.[24] Secondly, he proposes that the graphic representation of the corresponding diphthongs would be affected by the presence of a tautosyllabic sibilant.

§38.6. This paper aims to elucidate the challenges inherent in maintaining the conventional interpretation from a purely Mycenaean perspective. It seems probable that the restoration of the sibilant took place in Mycenaean times, given the clear indications of the articulatory weakness of intervocalic aspiration in the texts available to us. Otherwise, the differentiation of the dative-locative plural endings of the first and second declensions (-āhi / āï, –oihi / oiï) from the singular ones (-āi, –ōi) would be very poor, especially in the first declension, as seen below:

–āhi / āï :: –āi

–oihi / oiï :: –ōi

Aspiration derived from the inherited sibilant in Mycenaean

§39.1 The inherited sibilant of the proto-language underwent lenition in Greek both in the initial position before a vowel and in the intervocalic position, cf. a2-te-ro /hateron/ (PY Ma 365.2) < *sm̥-tero-m, e-e-si /ehensi/ (KN Ai(1) 63.1, Sd 4422.b) < *h1s-enti, –u-jo /hūi̯os/ (TH Gp(1) 227.2) < *suHi̯-o-s. Furthermore, it evolved in contact with a sonorant, although the situation of the consonant clusters that gave rise to the first compensatory lengthening in Mycenaean remains unclear. This is evident in spellings such as a-ni-ja (KN Sd passim, PY Ub 1315.1.2.3), pa-ra-wa-jo (KN Sk 789.B, 8100.B, PY Sh 737), or pi-ra-me-no (KN E 36, PY Jn(1) 389.2, TH Fq(1) 798.3), demonstrating that the sibilant is no longer preserved as such — otherwise, we should expect those terms to be written *a-si-ja, *pa-ra-u-sa-jo, and *pi-sa-me-no. However, it is not possible to determine whether it had evolved into an aspiration (/anhiā-, parawhaio-, philhameno-/?), resulting in the gemination of the sonorant as in Aeolic (/anniā-, parawwaio-, phillameno-/?), or the lengthening of the vowel of the preceding syllable as in most dialects of the first millennium (/āniā-, parāwaio-, phīlameno-/?).

§39.2. Conversely, the aspiration from the lenition of the inherited sibilant constitutes a fully-fledged phoneme in second-millennium Greek, despite the absence of its graphic notation in Mycenaean, given that the Linear B script lacks specific syllabograms for its representation, except for a2, cf. a3-ki-a2-ri-ja /Aigihaliā/ (TH Of 25.1), si-a2-ro /sihalons/ (PY Cn(2) 608.1), pa-we-a2 /pharweha/ (KN Ld(2) 786.B, 787.B, 788.B, MY L 710.2, Oe 127). With all the other vowels, its representation is achieved through the use of different types of graphic hiatuses such as a-re-pa-zo-o /aleiphadzohos/ (PY Un(1) 267.2), e-ke-e /hekhehen/ (PY Eb 297.1.2, Ep 704.5.6) or ke-ra-i-ja-pi /kerahiāphi/ (KN Sd 4450.a). Nevertheless, the representation of this aspiration is not universal, as there are numerous instances in which it is not graphically explicit, cf. ke-ra-ja-pi (KN Sd passim, Sf(1) 4428.a), ko-ri-ja-da-na / ko-ri-a2-da-na (MY Ge 605.2B.3B / MY Ge 605.4B.5, PY Un(1) 267.5), me-nu-wa / me-nu-a2 (KN Sc 238, V(2) 60.3, Xd 7702, PY An(4) 724.2 / PY Aq 218.14, Qa(1) 1301), o-pi-ja-ro / o-pi-a2-ra (TH Av 106.2 / PY An(3) 657.1), pa-we-a (KN Lc, Ld, L passim), tu-we-a / tu-we-a2 (PY Un(1) 267.3 / HV X 4.2), etc.[25] It is important to highlight that this phenomenon encompasses the representation of aspiration resulting from the evolution of the inherited yod,[26] cf. qe-te-a / qe-te-a2 (KN Fp(2) 363.1 / PY Un(3) 138.1, TH Wu 51.γ, 65.γ, 96.γ). Moreover, it has been observed that the use of a2 is particularly rare in Knossian documentation,[27] to the point of having been related to the psilosis of the Cretan dialect in the first millennium.

§39.3. In any case, these vacillations account for the instability of the aspiration as an independent phoneme in Mycenaean.[28] Otherwise, it is probable that a greater number of syllabograms would have been created for its representation, rather than solely a2. Furthermore, the use of graphic expedients to represent it would have been more consistent.

§39.4. It can be reasonably assumed that the inherited dative-locative plural endings of the first and second declensions would have evolved in Mycenaean to a point where they would be very poorly differentiated from singular endings, especially in the first declension:

PIE *-eh2si, *-oi̯si > PG *-āhi, *-oihi > Myc. *-āhi / –āï, *-oihi / –oiï

§39.5. Given this situation, it is likely that the intervocalic sibilant should have been already restored in Mycenaean times by analogy with the third declension, cf. ti-ri-ṣị (PY Ub(1) 1318.4), ka-ke-u-si (PY An(7) 129.7, Na(1) 104.B), or that the evolution of Mycenaean involved the extension of the inherited instrumental plural ending to the expression of the dative-locative, creating –ais by analogy for the first declension.[29] If we accept Ruijgh’s interpretation, it becomes evident that both –Ca-i and –Co-i serve to represent these last two endings (-ais and –ois). The question thus arises as to how the endings of the instrumental plural in –Ca and –Co should be analyzed. According to the Dutch scholar, these are merely graphic variants aligned with the representation of diphthongs with a second element in –i. In Linear B, these diphthongs can be rendered in full writing or without this second element.

Distribution of the instrumental plural endings –Ca and –Co

§40.1. The instrumental plural endings –Ca and –Co have a very limited distribution. They are mainly documented in the Pylos Ta series, namely with thematic adjectives modifying nouns with the postposition –pi, as well as a feminine perfect participle, cf. e-re-pa-te-jo ‘made of ivory’ (PY Ta 642.3, 707.1.3, 708.3, 710.1, 713.1, 713.3, 715.1, 721.1-5, 722.2), ku-ru-so ‘made of gold’ (PY Ta 714.2-3), ku-te-se-jo ‘made of laburnum wood’ (PY Ta 713.1), ku-wa-ni-jo ‘made of blue-colored glass’ (Ta 714.3), re-wo-te-jo ‘decorated with lions’ (PY Ta 722.2); qe-qi-no-me-na ‘carved’ (PY Ta 707.2, 708.2A). Furthermore, they would also be documented with the terms o-po-qo ‘blinkers’ (KN Sd passim, Sf(1) 4428.a)[30] and de-so-mo ‘binding’ (KN Ra(1) 1543.a, 1548.a) in Knossos.[31] The general opinion is that this distribution is due, on the one hand, to the functional spectrum of these endings, which would be limited to the instrumental plural, a category much less well represented in our texts than that of the dative plural and the locative plural. On the other hand, this distribution would also represent a state of affairs closely aligned with Proto-Greek. In this context, only a particular instrumental plural ending was preserved for thematic nouns, while the adverbial morpheme –phi was used to express this function more generally. However, the use of –pi with thematic nouns is also documented in Mycenaean, cf. e-re-pa-te-jo-pi (KN Se 891.A, X 7814.1) and e-re-pa-te-jo-pi o-mo-pi (KN Se 891.B) having instrumental value; mo-ro-ko-wo-wo-pi (PY La(3) 635) having locative value, and ma-ro-pi (PY Cn passim) with that value. Nevertheless, in the latter case, the stem of the toponym[32] remains uncertain. Regardless of the interpretation of the data presented, it is evident that Mycenaean innovates with respect to Proto-Greek. For instance, clear innovations are the creation of –ais, which is difficult to question in the case of qe-qi-no-me-na (PY Ta 707.2, 708.2A),[33] and the extension of –pi to thematic nouns.

§40.2. As previously stated, Ruijgh’s hypothesis posits that –Ca and –Co in the aforementioned examples represent graphic variants of –Ca-i and –Co-i. It is worth noting that the scribe designated as Hand 2, to whom the Pylos Ta series is ascribed, also uses long graphic endings, cf. a-ke-ti-ri-ja-i (PY Fn 187.15), pa-ta-jo-i- (PY Jn(1) 829.3), te-o-i (PY Fr(1) 1226.1), but not, as far as we know, the Knossian scribes identified as Hand 126 and Hand 128, authors of the Ra and Sd, and Sf series, respectively. In any case, it seems probable that de-so-mo should be interpreted as a distributive singular, a category well-known in ancient Greek and texts written in Linear B, cf. Sintaxis 25-26. It appears as a component of the swords (or daggers) recorded in the Ra series, which consistently lists several items per tablet. Thus, de-so-mo likely refers to one binding per sword. The interpretation of o-po-qo is considerably more complex. It is commonly accepted that the term refers to the blinkers of the two draught horses of Mycenaean chariots, which would have meant that four blinkers were used per chariot.[34] However, blinkers are not documented in Greece until much later[35] and are designated by the terms παρώπια (Hdn.Gramm. 3,1.364.35; Poll. 1.140.7, 2.53.4, etc.) and ἀνθήλια / ἀντήλια (Poll. 10.54.5; Ael.Dion. pi.24.1, etc.), compiled by lexicographers from the 2nd century CE onwards. It can thus be posited that o-po-qo may be used to refer to a singular component of the chariot, regardless of its specific nature.[36]

§40.3. In essence, the majority of the examples are found within the Pylos Ta series, and solely with adjectives that are dependent on nouns where –pi is used. The number of examples is certainly striking. Nevertheless, the nouns in –pi also agree with thematic adjectives in –Co-i, as evidenced by the Theban tablet TH Uq 434, where the editors read pa-ro te-qa-jo-ị q̣ạ-si-re-u-pi in the heading. This syntagm is formed by the preposition pa-ro (= παρά), the adjective te-qa-jo ‘Theban’ in the dative plural, and the noun qa-si-re-u (= βασιλεύς) with the morpheme –pi, cf. Aravantinos et al. (2008).[37] Regarding the aforementioned adjectives from the Pylos Ta series, it is important to mention this series’ peculiarities, which include erasures, scribal errors, etymological writing of compounds, the use of alleged adjectives in –ēu̯-, and different word order patterns (Jiménez Delgado 2010:53–54). These peculiarities seem to indicate an effort by the scribe to adapt the information to the format of the tablet (cf. Palaima 2011:68–69). Hypothetically, this may be related to the use of the short –Ca and –Co instead of –Ca-i and –Co-i.

The graphic representation of diphthongs in Linear B

§41.1. Consistent with the orthographic conventions observed in the extant texts (Melena 2014:89–127; Docs3 113–125), the notation of the second element of a diphthong is only obligatory when u is involved, but not when i is involved. However, the i is also observed, particularly in Knossos, with some examples in other centers, cf. Melena (2014:92–98). It should be noted that a significant number of instances are in pre-Hellenic terms or of questionable interpretation, cf. ka-da-i-so / ka-da-si-jo (KN De 5018.B / PY An(3) 519.2), ro-i-ko (PY Va(1) 482), or ta-i-da (TH Ug 13), however, there are also cases of identifiable terms, cf. e-u-da-i-ta /Ehudaitās/ (KN Dl 47.1), da-i-ja-ke-re-u /Dai-agreus/ (PY Aq 218.3), ko-i-no /skhoinos/ ‘rush’ (MY Ge 606.7), or wo-i-ko-de /woikonde/ ‘to the (god’s) house’ (KN As(2) 1519.11). Furthermore, the diphthong ā̆i can be represented with two special syllabograms, a3, which is exclusively used at the beginning of a word, and ra3, which can be used, for instance, to indicate the nominative plural of first-declension nouns, cf. pi-je-ra3 /phielai/ (PY Ta 709.1) or di-pte-ra3 /diphtherai/ (PY Ub 1315.1), cf. Melena (2014:54–60). Nevertheless, the full spelling of the dative plural endings, if one accepts that they were read /-ais/ and /-ois/ in Mycenaean, is noteworthy, given the absence of such notation in the corresponding nominative plural endings, which were /-ai/ and /-oi/. In this regard, Ruijgh (1967:24) relates this full spelling to that of the Cretan toponym pa-i-to and its adjective pa-i-ti-ja/-jo, which are never written without –i– despite their frequency. Indeed, there are over fifty instances of the toponym and more than ten of the adjective in various series, including one on a tablet from the Room of the Chariot Tablets,[38] Og(1) 180.1. However, the only documented references of pa-i-to are Knossian and it is a pre-Hellenic place name, cf. PA-I-TO (HT 97a.3, 120.6), therefore, it is not possible to confirm with certainty that we are dealing with a diphthong. In any case, Ruijgh, like Doria (1965:40), proposed that this full spelling could be considered a means of indicating that the second element is followed by a tautosyllabic sibilant in the Cretan toponym and the dative plural endings.

§41.2. Identifying parallels for this writing convention is a challenging endeavor,[39] with the most consistent parallel presenting interpretive difficulties with regard to its ending. I am referring to the pronominal form pe-i (PY An(3) 519.15, 654.7, 656.5.8.14.16.19, 657.11.14, 661.7.13, Na(1) 395.B), which is evidently connected to Hom. σφι / σφίσι. In this form, we encounter the same issue as with the dative plural endings that we are currently examining. The spelling has been interpreted as the notation of an intervocalic aspiration /sphehi/, which would have derived from a protoform /sphesi/. It is not possible to state with certainty whether this is the case, and the related forms of the first millennium do not assist in resolving the question either. In addition to the Homeric forms mentioned above, which are Attic-Ionian, σφεις (IG 5(2) 6.10, 18, Tegea, fourth c. BC) and σφέσι (SEG 37.340.15, Mantineia, fourth c. BC) are documented in Arcadian, which have been considered a continuation of the Mycenaean form. In his appendix to te Riele (1987), Frederik Waanders proposes that both σφεις and σφέσι are the outcome of the Mycenaean form following the loss of the intervocalic aspiration. This would have been remodelled through an analogy with the dative plural endings of the nominal declension. Nevertheless, as has been demonstrated, the loss of intervocalic aspiration is a process that had already began in Mycenaean. Conversely, the original form in Proto-Greek remains uncertain. However, if the original form was *sphei̯, as is a plausible hypothesis (Petit 1999:263–265, 306–307, 326–327), it is probable that the full spelling of the diphthong was a method to circumvent a monosyllable (Melena 2014:125), or that the Mycenaean form had been reshaped as /spheis/ through analogy with dative plural endings.

§41.3. In short, the full writing of the diphthong in Mycenaean dative plural endings may be attributed to a tautosyllabic final sibilant. It is similarly conceivable that this was an intentional endeavor by the scribes to differentiate the dative plural from the singular. However, this strategy does not apply to the nominative or accusative of the first and second declensions, therefore it is unclear why it would apply in the case of the dative. A possible explanation could be its frequency and the fact that the recipients of the products recorded on the tablets are not usually accompanied by logograms determining their number, as is the case with these products, which tend to be written in the nominative/accusative.

From Proto-Greek to Mycenaean and from Mycenaean to the first millennium BC

§42.1. According to the data extracted from Mycenaean and first-millennium dialects, we can assume that Proto-Greek had the following dative, locative, and instrumental plural endings (García Ramón 2017:655):[40]

Dat.-loc. pl.: –āsi, –oi̯si, –si

Instr. pl.: –ōi̯s, –phi

§42.2. In Mycenaean, there are developments in this context. The most prominent of these is the extension of the ending –phi to the locative plural and the analogical creation of –ais. However, as has been shown, the interpretation of the documented endings remains uncertain. The two principal hypotheses are as follows:

- Conservative hypothesis, whereby the instrumental would remain partially differentiated:

Dat.-loc.: –āhi, –oihi, –si, –phi

Instr.: –ois, –ais, –phi

The distinction of the instrumental plural ending is partial because it is only well differentiated in the second declension, where –phi is also documented; –ais is a minority innovation compared to –phi in the first declension.

- Innovative hypothesis based on a partial syncretism of the three values:

Dat.-loc.-instr.: –ais, –ois, –si

Instr.-loc.: –phi

This syncretism is partial because, on the one hand, in the Mycenaean dialect –ois would replace –oisi, resulting in the creation of –ais in the first declension; on the other hand, –phi is used to distinguish the locative and the instrumental from the dative in the plural.

§42.3. In this context, we would like to propose an intermediate hypothesis:

- Intermediate hypothesis: The articulatory weakness of intervocalic –h– would have led to the replacement of –āhi and –oihi by –ais and –ois and, consequently, to the extension of –phi to differentiate the locative and the instrumental from the dative plural.

§42.4. In the first millennium, dative plural endings express dative, locative, and instrumental values. The most common endings are -ηισι / -ῃσι, -αισι, -ᾱσι/-ησι, -αις; -οισι, -οις; -σι, -εσσι, cf. Deplazes (1991). The dialectal distribution is complex, distinguishing between long and short endings, with the short endings ultimately imposed, and with very specific intradialectal phenomena (e.g., -ασσι in Tarentum and Heraclea; the use of -αισι / -οισι to distinguish the dative from the accusative plural in areas where the second compensatory lengthening produced a diphthong, as in Lesbian), as opposed to other very general ones (as in the case of -εσσι[41] or the apocope of -αισι and -οισι). The origin of these endings is complex, as they emerged through two different phenomena: the choice between the endings inherited from Proto-Greek and the post-Mycenaean analogical processes. In any case, Mycenaean has no continuity in any dialect of the first millennium on this point, since –phi is lost in the process of syncretism.[42]

§42.5. Although the evolution of the dative plural endings after the fall of the palaces is a question beyond the scope of this paper, it is interesting to note that in the evolution proposed by Deplazes (1991:157–161), the most detailed study of these endings to date, the restoration of the intervocalic sibilant in –āsi and –oisi would precede the loss of –phi. This would have occurred while –si and –phi remained functionally differentiated in the third declension, as long as the motivation for its restoration was to clearly distinguish the dative-locative from the instrumental plural.[43] Only with the complete loss of this last morpheme would the process of syncretism of the instrumental with the dative-locative come to an end, with dialects opting for the long or short forms. As we have already seen, the loss of this morpheme is post-Mycenaean — probably not much later, given the functional extension of the morpheme in Homer and its disappearance in the first millennium — however, the analogical creation of –ais is already observed in the tablets.

§42.6. In conclusion, we can say that the main problem in the transition from the second to the first millennium is posed by the long endings. If the inherited locative plural endings were retained and the sibilant was restored in them, this restoration must have taken place before the Mycenaean period. This is supported both by evidence from similar restorations and by the articulatory weakness of the intervocalic aspiration, which was already present in the Mycenaean period.[44]

Conclusions

§43.1. The Mycenaean endings for the expression of values related to the dative plural are as follows: –Ca-i, –Ca, –Co-i, –Co, –si and –pi. This plethora of possibilities points to a stage where the syncretism of the dative, locative, and instrumental had not yet occurred.

§43.2. Mycenaean is generally considered to represent a conservative situation, closer to Proto-Greek than to first-millennium Greek, in which the dative and locative would already be syncretized, but not the instrumental, so that the Linear B endings would read /-āhi/, -/ais/, /-oihi/, /-ois/, /-si/, and /-phi/, respectively. This conservative proposal, however, would lead to a certain indifferentiation of the endings of the first and second declensions with those of the singular. Given the articulatory weakness of the aspiration in intervocalic position already in Mycenaean, /-āhi/ would be practically homophonic with /-āi/, and /-oihi/ would differ from /-ōi/ basically by different vowel quantities. This lack of distinction within these two declensions seems to indicate that the restoration of the sibilant, which is said to have given rise to -ᾱσι/-ησι, -ηισι / -ῃσι, -αισι, and -οισι in the first millennium, should have already taken place, or would be at least in progress, in Mycenaean times. Moreover, the restoration of the intervocalic sibilant in the third declension and the aorist and sigmatic futures had effectively taken place in the Mycenaean period.