2025.04.25 | By Gregory Nagy

A plane tree, in a corner of Syntagma Square, Nafplio. Image via Flickr (license). At §13 in the essay that follows, I explain why I think that the tree pictured here is fitting symbol of the ideals considered in this essay.

§0. Empires may take many different shapes, depending on their natural as well as political environments. Correspondingly, empires may collapse because of catastrophes that likewise involve, again, natural as well as political causes. In the summer of 2025, on June 30 and July 1 2 3, in the city of Thessaloniki, I offer a four-day seminar that takes into consideration a variety of such causes, and I focus on the civilizations of two empires that collapsed around the same time, toward the end of the second millennium BCE.

§1. One of these two civilizations is known to archaeologists today as Mycenaean—or, to say what it was called in Homeric language, Achaean—while the other of the two is known as Hittite. Relevant is a book by Eric H. Cline, who gives his work a most provocative title: 1177 B.C.: The Year Civilization Collapsed (Princeton University Press 2014; a significantly revised second edition appeared in 2021). As the author argues in this influential book, what happened to the civilizations of the Mycenaeans and of the Hittites—as also to other civilizations, especially in the Near East, is a prime example of what he calls a collapse of “civilization” itself.

§2. Even the civilization of pharaonic Egypt, in the era of the New Kingdom, was threatened with a decline that could have led eventually to a complete collapse, as in the case of the Mycenaeans and the Hittites, though, in the case of Egypt, its New Kingdom managed to survive well into the first millennium BCE. True, the ancient empire of the Egyptians underwent many of the same kinds of natural as well as political catastrophes—both short-term and long-term—that afflicted the empires of the Mycenaeans and the Hittites—except for a “mega-drought,” as Cline’s book calls it (p. xix), lasting for centuries, which plagued most empires of the Mediterranean region in the Late Bronze Age. In this one case, Egypt would have been an exception, since its territory kept on being fed by the Nile.

§3. One kind of affliction, though, that the ancient Egyptians did in fact share with the Mycenaeans and the Hittites is a wave of disastrous invasions by migrant populations. As his starting point, Cline’s book focuses on one particular year, 1177 BCE, which he estimates is a decisive time when, according to one particular ancient Egyptian source, the mighty state of Egypt was invaded by a massing of migrants who are nowadays generally described as “Sea Peoples.” According to ancient Egyptian sources, these invading migrants or would-be immigrants were on one particular occasion massively defeated—the date is estimated at 1177 BCE—by the joint armed forces of pharaonic Egypt—in both land-battles and sea-battles. Despite the victory described in the Egyptian sources, however, Cline’s book shows how this invasion, along with a host of other such comparable critical events that happened in that era, signaled a gradual decline for the civilization of Egypt—a decline that lasted for centuries thereafter. Moreover, around the same time, the neighboring civilizations of the Mediterranean region and beyond were likewise going into a decline and, in most of these cases, the decline was so steep that it eventually led to utter collapse. Among the civilizations that not only declined but actually collapsed in that era of decline were the Mycenaeans and the Hittites.

§4. It is commonly thought that such decline or even collapse was actually caused, at least in part, by the “Sea Peoples” who as we saw were described in Egyptian sources as invading marauders. But the realities of the time must have been far more complicated, as we see, for example, in a work by a former student of mine, Jeffrey P. Emanuel, https://chs.harvard.edu/jeffrey-p-emanuel-cretan-lie-and-historical-truth-examining-odysseus- raid-on-egypt-in-its-late-bronze-age-context/, who argues that the Homeric Odyssey actually reveals traces of the kind of event that pharaonic Egyptian sources describe as happening in, say, the year 1177 BCE. The bibliography of Cline’s book lists other relevant works of Emanuel.

§5. In any case, even the activities of such marauders as the “Sea Peoples” may have resulted from the same pattern of decline throughout the Mediterranean world and beyond. For example, at least some of the unstable populations that Egyptian sources described as invading marauders and that experts today describe more vaguely as “Sea Peoples” may have been migrants who were escaping from collapsing realms of their own and who were seeking to resettle as immigrants in relatively more stable realms such as pharaonic Egypt.

§6. In this connection, Cline’s book (ed. 2 p. 12) makes a most relevant observation, and I quote: “[T]he Sea Peoples may well have been responsible for some of the destruction that occurred at the end of the Late Bronze Age, but it is much more likely that a concatenation of events, both human and natural—including climate change leading to drought and famine, seismic disasters known as earthquake storms, internal rebellions, and ‘systems collapse’—coalesced to create a perfect storm that brought this stage to an end.”

§7. The seminar cited at §0 analyzes how such a “perfect storm,” resulting from a “concatenations of events,” could be rationalized by way of myths. For example, attempts at resettlement could have been rationalized, if they succeeded, as myths about immigration. Conversely, changes in régime could have been rationalized as myths about successful invasions.

§8. Here I bring into sharper focus the two great empires of the Mycenaeans and the Hittites. One of these two, the Mycenaean Empire, was both land-based and sea-based. It dominated a land-mass that matches today, roughly, the modern European state of Greece, but it dominated not only the land-mass that corresponds to Greece today but also the Aegean Sea, which borders on this land-mass and which includes hundreds of islands, large and small, that are crowded into this same sea. But this Aegean Sea, which is basically the eastern zone of the overall Mediterranean Sea, also borders on the second of the two ancient empires under consideration, known to archaeologists as the Hittite Empire. By contrast with the Mycenaean Empire, this rival empire was only land-based, dominating the land-mass that corresponds today, again roughly, to the modern state of Türkiye, better known to English-speakers as “Turkey.” Although Türkiye is nowadays considered to be European by many of its inhabitants, it is situated in a land-mass that had normally been considered to be non-European and thus “Asiatic” in the ancient world—witness the modern term “Asia Minor,” derived from an ancient name Asiā that had actually referred, in ancient Greek sources, to a supposedly Asiatic and thus non-European land-mass that was separated by the Aegean Sea from the land mass that was already in ancient times known as Europe.

§9. Of special interest for me is the fact, established by archaeological evidence, that both the Mycenaean Empire and the Hittite Empire collapsed toward the end of the so-called Bronze Age. This twin collapse led to an era that has conventionally been called a Dark Age, extending from the end of the second millennium BCE into the first few centuries of the following first millennium. As we can see in the course of our reading relevant evidence, however, the “darkness” of the Dark Age is contradicted by myths that stem from this era and that tell about the era that followed the Twin Collapse of Empires. And these myths also tell about the earlier era when the Twin Empires were still in power. Moreover, there have survived texts from both these empires—texts written on clay tablets that were accidentally baked in the fires that had put an end to royal palaces administering such empires. These texts, written on clay tablets that were in some cases (as I argue) “rough drafts” of “final drafts” that are no longer extant, provide us with indispensable information about the administrative histories of the empires.

§10. Besides reviewing the basic information stemming from the administrative texts of the palaces of the Mycenaean and Hittite empires in the latter half of the second millennium BCE, the seminar analyzes narratives, stemming from later written sources produced in the latter half of the first millennium BCE, concerning European Greeks as well as Asiatic Greeks and non-Greeks in the era of the Persian Empire and beyond.

§11. In what follows I offer a brief syllabus, divided into Day 1 / 2 / 3 / 4, which is tied to essays containing special references to ancient primary sources that are paraphrased in these essays. Included for analysis are samplings of relevant Greek passages, all translated into English. All the secondary sources are available online and are free of charge.

Day 1. The Twin Empires and their colossal collapse. How this collapse is related to myths about a war between Achaeans and Trojans. And how the myths about a Trojan War are related to myths about a Dorian Invasion and an Aeolian Migration.

To be covered in Day 1: Parts I/II respectively of the essay “Greek myths about invasions and migrations during the so-called Dark Age”.

Day 2. The Ionian Migration; patterns of displacement and colonization. About Ionians before and then during the era of the Lydian Empire in Asia Minor. Also, about Ionians during and then after the era of the Persian Empire.

To be covered in Day 2: Part III of the essay cited for Day 1, “Greek myths about invasions and migrations during the so-called Dark Age”. Also this essay: “Thinking Iranian, Rethinking Greek”.

Day 3. On patterns of massive interventionism and invasion. To be covered in Day 3: the essay “Mages and Ionians”..

Day 4 General Discussion, both hours.

The discussion includes this essay by Olga M. Davidson: “An occlusion of Xerxes in Persian medieval epic”.

§12. Davidson’s essay focuses on an event reported in the History of the Greek author Herodotus, which first circulated in the Greek-speaking world during the last decades of the fifth century BCE, and I quote from her essay:

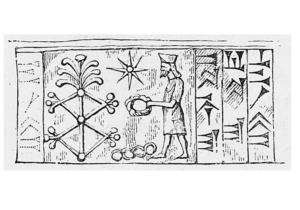

The historian reports (7.21) that Xerxes, at the beginning of his expedition against the Hellenes on the other side of the Aegean Sea, finds a plane tree that enthralls him with its beauty: he treasures this tree so dearly that he decorates it with gold ornaments and arranges for it to be guarded by one of his elite troops known as the Immortals. A later Greek author, Aelian (Varia Historia 2.14), ridicules Xerxes for idolizing a tree, but this worshipful gesture of the king is in fact true to the royal traditions of his dynasty. As Pierre Briant, an expert in the history of the Persian Empire, points out, the kings of the Persian empire could be pictured as worshipping the plane tree as a tree of life.

Seal of Xerxes. Perrot & Chipiez 1890 fig. 497, via Briant 2002 fig. 30.

Seal of Xerxes. Perrot & Chipiez 1890 fig. 497, via Briant 2002 fig. 30.

This act of adoration is reproduced at the beginning of an opera by Handel. Although Handel’s Xerxes differs from the historical emperor in many ways, they are both men given to intensely passionate acts, as we see and hear in the breathtaking aria, “Ombra mai fu.”

§13. The featured image at the beginning of my essay here is relevant to that famous plane tree so loved by Xerxes, mighty ruler of the Persian Empire, which he honored as his very own Tree of Life by decorating it with ornamentation fit for a king—or, better, for a king of kings. The fame of the king’s beloved plane tree has been perpetuated, as we saw in §12, by the corresponding fame of an aria composed by Handel for his opera about Xerxes. This aria, loved by lovers of music worldwide, features the intense countertenor voice of the king himself singing his song of adoration for his beloved plane tree: Ombra mai fu | di vegetabile, | cara ed amabile, | soave più. ‘Shade there never was | of any plant | so dear and lovely | or any more sweet’. To my mind, a fitting new symbol of this musical object of love may well be the plane tree gracing a corner of Syntagma Square in Nafplio: under its shade flourish countless memories of happy conversations about unforgettable travels in Hellenic realms. Such memories are now being encoded in the ornamentation for a new Tree of Life. The “ornaments” consist of photos, videos, and written comments contributed by fellow-travelers who participated in a travel-study program that is signaled here: “A reader for travel-study in Greece, keyed to the Scrolls of Pausanias.”