2022.09.26 | By Gregory Nagy

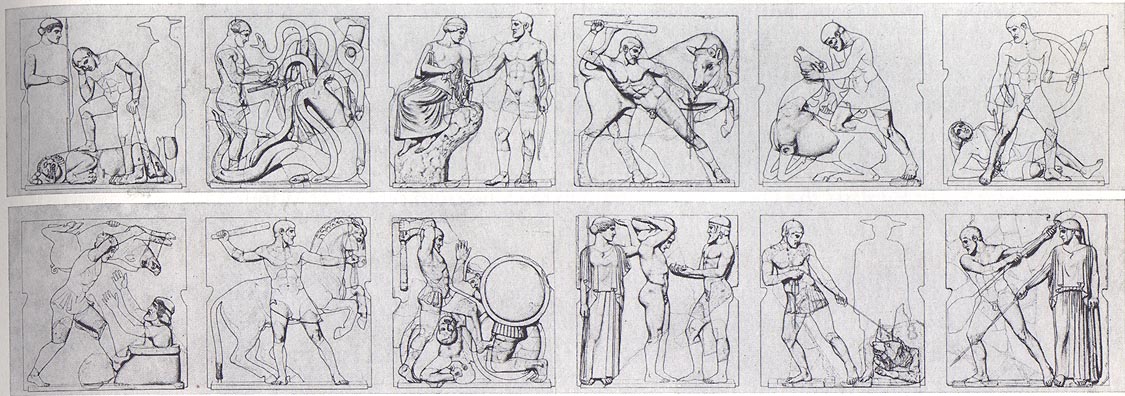

§0. In the preceding essay, I was looking at the Olympics from the standpoint of an earlier time in Olympia, around 600 BCE, which is approximately the time when the Temple of Hērā was built there, and I stopped looking, for the moment, at the “classical” time, in the mid-fifth century, when the Temple of Zeus was built next to it. Looking at the “preclassical” Olympics, I argued, we could view this festival through a wider lens, since we could see the relevant history from an earlier as well as a later perspective. If we were to consider only the Temple of Zeus, by contrast, the lens would be more narrow, since we could then view the Olympics mostly from the standpoint of the politics driven by the state of Elis. Such a later view, as I will now argue, can be described as “occlusive” by contrast with the inclusive earlier view. But I deliberately say “occlusive,” not “exclusive,” in describing the “classical” view. To illustrate my point, I will be concentrating on the twelve metopes of the Temple of Zeus. As we will see, the myths about the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs as pictured in the sculptures of these twelve metopes are hardly exclusive, since we read about the same Twelve Labors in written sources that narrate myths about the deeds of Hēraklēs. But the myths about the Twelve Labors as pictured in the twelve metopes of the Temple of Zeus they are indeed occlusive, in the sense that the picturing of the Labors shades over some aspects of these myths while highlighting other aspects. And this kind of occlusiveness must have been deeply appreciated by Pausanias when he looked up from ground zero at the metopes on high while visiting the Temple of Zeus at Olympia. His appreciation shines forth, I think, in the artistrty of his own rhetoric of occlusiveness in response to the what he sees in the visual art of the twelve metopes.

§1. While describing the Temple of Zeus in Olympia—that most celebrated building located in that most celebrated site designated for a most celebrated seasonally recurring event, the Olympics—the traveler Pausanias confines to a single paragraph, 5.10.9, his description of the heroic deeds represented by the marble relief sculptures of the twelve metopes looming above the two sets of enormous bronze doors that opened into the front and into the back of the Temple. There were six metopes in the front and six in the back, each one of which narrated each one of the canonical Twelve Labors of the hero Hēraklēs. Such bravura in compressing the description here into one single solitary paragraph is especially striking when we consider the lengthy and detailed accounts provided by Pausanias about the rest of the Temple. Starting at 5.10.10, where Pausanias enters the temple, his description slows down and lingers, providing a multitude of details about the colossal statue of Zeus as also about all the other wonders to be seen inside the Temple of Zeus in the days of Pausanias, that is, in the second century CE, when the whole site of Olympia was still in safe hands. So, why is Pausanias in such a hurry to account for the metopes on the outside before he makes his entrance inside the temple? I think is is because this single solitary paragraph crafted by Pausanias about the metopes gracing the Temple of Zeus is designed not only to describe but also to retell, in a most compressed manner, the canonical Twelve Labors of the hero Hēraklēs. It is the retelling that motivates the compression, which to my mind is a masterpiece in verbal artistry. In particular, I think that Pausanias is a master of what I call the rhetoric of occlusiveness.

§2. Here, then, is the text of Pausanias 5.10.9, followed by my working translation:

{5.10.9} ἔστι δὲ ἐν Ὀλυμπίᾳ καὶ Ἡρακλέους τὰ πολλὰ τῶν ἔργων. ὑπὲρ μὲν τοῦ ναοῦ πεποίηται τῶν θυρῶν ἡ ἐξ Ἀρκαδίας ἄργα τοῦ ὑὸς καὶ τὰ πρὸς Διομήδην τὸν Θρᾷκα καὶ ἐν Ἐρυθείᾳ πρὸς Γηρυόνην, καὶ Ἄτλαντός τε τὸ φόρημα ἐκδέχεσθαι μέλλων καὶ τῆς κόπρου καθαίρων τὴν γῆν ἐστιν Ἠλείοις· ὑπὲρ δὲ τοῦ ὀπισθοδόμου τῶν θυρῶν [ὁ] τοῦ ζωστῆρος τὴν Ἀμαζόνα ἐστὶν ἀφαιρούμενος καὶ τὰ ἐς τὴν ἔλαφον καὶ τὸν ἐν Κνωσσῷ ταῦρον καὶ ὄρνιθας τὰς ἐπὶ Στυμφήλῳ καὶ ἐς ὕδραν τε καὶ τὸν ἐν τῇ γῇ τῇ Ἀργείᾳ λέοντα.

{5.10.9} At Olympia, most of the deeds [erga] of Hēraklēs are [represented] there. Above the doors of the Temple have-been-made [passive of the verb poieîn] [the following representations]:

- the hunting-down of the Arcadian Boar,

- the matters with regard to Diomedes of Thrace

- also with regard to Gēryonēs in Erytheia

- also, in connection with Atlas, what [weight] he is carrying, [the weight] that he [= Hēraklēs] is about to receive-in-relay [ek-dekhesthai]

- and [now] he is purging the land, [getting rid] of the manure, for the sake of the people of Elis.

Then, looming above the doors of the rear-chamber [of the Temple],

- there he is, removing the band-that-girds-the-waist of the Amazon

- and then there are the matters having to do with the Hind

- and [having to do with] the Bull at Knossos

- and [having to do with] the Birds at Stymphēlos

- also having to do with the Hydra,

- and, in the land of the people of Argos, with the Lion.

§3. Earlier, when I described as “canonical” the myth of the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs, I meant simply whatever was generally considered to be the standard set of twelve āthloi or ‘labors” attributed to Hēraklēs in the era of Pausanias. As I hope to show, the syntax of Pausanias here is meant to convey his own attitude about the canonicity of the Twelve Labors as represented in the twelve metopes of the Temple. In this context, I agree with a relevant point made by Greta Hawes (2021:58): wherever Pausanias expects his readers to be familiar with a given myth or set of myths, he tends to elide details. But I would add that such elision can in some cases becomes an artistic challenge: how to formulate familiar myths in a way that challenges the intelligence and the sensitivity of your readers? In the case of the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs, Pausanias rises to the occasion, I think. As I already signaled earlier, he is creating a masterpiece of artistic compression in his mode of retelling the myths as already retold in the metopes of the Temple of Zeus.

§4. My working translation of the text as I presented it right after my quoting the original Greek of Pausanias has been designed to convey how the verbal art of our traveler here has actually imitated the visual art that retold the myths that are represented in the marble relief sculptures of the metopes. In my translation, I have added signposts for such verbal artistry by way of formatting separately, in bullet-point style, each one of the twelve compressed retellings that correspond to each one of the Twelve Labors—as retold not only in the metopes but also in the compressed descriptions by Pausanias. Even the syntax of my translation, punctuated by way of bullet points, is meant to imitate the syntax of connections that Pausanias has constructed in framing his own retellings while describing the twelve narratives. Thus I have signaled, by way of literal translations that are made to correspond as closely as possible to the word-order we find in the original Greek, the artistic elisions we find in the transitions from one phase of retelling to the next.

§5. Among the elisions, I think, is a case of outright omission. When Hēraklēs brings the Hound of Hādēs from the realm of darkness and death to the realm of light and life, this deed of his should be the Twelfth of the Twelve Labors in terms of the sequence of Labors as narrated in some canonical narratives, as in the Herakles of Euripides, lines 359–427 (commentary in Nagy 2022.04.04). But the local version of the Labors as transmitted by the state of Elis in the narrative sequence of the metopes gracing the Temple of Zeus requires that the Twelfth Labor be the clearing of the Stables of Augeias, as I argued in Part I Essay 9: from Boar to Horses to Cattle to Apples to [Hound to] the Stables of Augeias. Accordingly, the bringing of the Hound, which would have to take eleventh place in the retelling by Pausanias, is simply elided here in his description of the metopes. Our traveler had already made room for a detailed retelling about the Hound, by way of another local version, at an earlier point in his far-flung journeyings, at 3.25.5–6 (Nagy 2022.04.04).