2022.08.15 | By Gregory Nagy

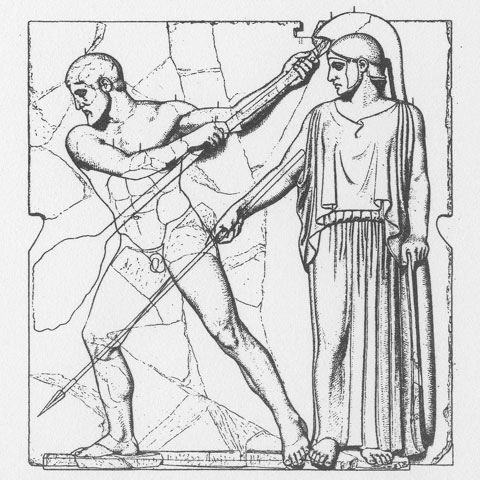

§0. Up to now, I have been reconstructing the mythological persona of the Greek hero Hēraklēs as a prototypical Strong Man by tracing him backward in time, back to the earliest reconstructable phases of myths that told his story. Here in Essay 9, I will trace such myths forward in time, relying on methods I already previewed in the Excursus of Essay 5. Applying the methodology of “reconstructing forward” as I defined it in Essay 5, I will focus on a myth that tells about a deed performed by Hēraklēs in the service of a king by the name of Augeias (the latinized spelling is Augeas). We see a narration of this myth in the visual art of relief sculpture adorning the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, which was built by the state of Elis in the mid-fifth century BCE. The temple displayed twelve narrative frames for these sculptures—the architectural term for such a frame, which I have already used in Essay 4, is metope—and the twelve metopes told the stories of twelve myths known as the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs. Of the twelve metopes, the last in the narrative sequence, Metope 12, pictured the myth that I have chosen as the focal point of my essay: we see in this metope the hero Hēraklēs perfoming a deed in the service of the king Augeias. But what is the deed ? What is the hero’s Labor here? In the line drawing of Metope 12 that I show here, we can see the essence of the deed being performed: Hēraklēs is shown in the act of shoveling an immeasurable accumulation of manure from the Stables of Augeias, and the hero’s laborious work is being supervised by his divine patroness, Athena. In my essay here, I will analyze the meaning of Metope 12 by forward-reconstructing three consecutive phases in the evolution of Hēraklēs as a mythological figure. Two of these phases are all too familiar by now—Indo-European and Mycenaean—but I will now add another phase that is as yet unfamiliar, post-Mycenaean.

§1. In Essay 4, I had analyzed an expanded narrative in the “Universal History” of Diodorus of Sicily (4.11.3–4.26.4), dated to the first century BCE, about all twelve of the âthloi or ‘Labors’ of Hēraklēs, and then I went back in time, backward from that relatively late source, back to the mid-fifth century BCE, the era when the Temple of Zeus at Olympia was being built. And I compared, briefly, the visual evidence of the twelve metopes gracing this temple. We saw here the Twelve Labors being narrated not by way of written text, as in the case of Diodorus, but by way of visual art. The relief sculptures of the metopes were telling their own story. And then, in what at first seemed in Essay 4 to be no more than an afterthought, I went back even further, further back in time, back to a time that predated by many centuries the building of the Temple of Zeus in Olympia—back to an early era when Homeric poetry was still in the making. At §16 of Essay 4, I highlighted Iliad 19.95–133, where we find a compressed narrative about, again, the Labors of Hēraklēs, the word for which is, again, âthloi (áethloi), at line 133. So, in Essay 4, I had already considered three different versions of myths about the Labors—two newer expanded versions and one much older compressed version—and then I went on to reconstruct still other versions that were even older than the compressed Homeric version. I described these even older versions, going further back in time, as Indo-European. And I concentrated on a central idea that all these versions had in common: that Hēraklēs was “a Strong Man in the service of a King.” My spelling Strong Man, I should add here, makes a distinction between the kind of man that was being reconstructed and another kind of man I would describe as a strongman, with lower-case s-. As I contemplate my own present time, with all its current horrors, I find it important to make such a distinction between Strong Man and strongman. For me the current usages of the word “strongman” evoke an entirely different story (as I ruefully explain in a different essay of mine, Nagy 2019.06.21).

§1.1. The oldest phases of deeds performed by Hēraklēs as a Strong Man in the service of a King, as I explained in Essay 4 §§14–20, can be reconstructed by way of using the methodology of linguists who compare not only the cognate languages stemming from the so-called Indo-European language family but also the cognate myths inherited by these languages. So, as we saw in Essay 4, such oldest phases of this mythological figure named Hēraklēs can be described as Indo-European.But there were evident complications, as we already started to see in Essay 4, when we reconstructed backward in time the Labors of Hēraklēs in terms of Indo-European myths about deeds performed by a Strong Man for a King.

§1.2. Such complications will now become even more evident as I begin to reconstruct the Labors of Hēraklēs by tracing them forward rather than backward in time, starting from Indo-European models. Here in Essay 9, I choose as my most useful point of departure the various Indo-European myths about a Strong Man and a King as reconstructed by Georges Dumézil in two books I have already noted in Essay 4: The Destiny of the Warrior (1970; in French, Dumézil 1969, second edition 1985) and The Stakes of the Warrior (1983b; in French, Part 1 of Dumézil 1971). Starting with such myths, I will look ahead in time to find relevant points of comparison in Greek sources. And the evidence of these sources will come from myths that concern not only the Labors of Hēraklēs but also what I already described in Essay 4 as the hero’s sub-Labors. In what follows, a primary point of interest will be a king who has a role both in the Labors and in the sub-Labors of Hēraklēs. That king is Augeias.

§2. To be contrasted with Augeias, king of Elis, is Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, who has a proper place primarily in the myths about the Labors of Hēraklēs, not in the myths about the hero’s sub-Labors. As we will see in what follows, where I rely once again on general methodology explained in the Excursus of Essay 5, such a distinction between the kings Eurystheus and Augeias can be highlighted by way of reconstructing the relevant myths forward in time, not backward.

§3. So, engaging in forward-reconstruction of Indo-European myths about a Strong Man and a King, I now focus on the myth about the Twelfth Labor of Hēraklēs as pictured in Metope 12 of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, a sacred site controlled by the state of Elis at the time when the temple was built, in the mid-fifth century BCE. We find a vivid retelling of the myth in the Library of “Apollodorus,” dating from the second century CE. According to “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; especially pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), as I now proceed to analyze here in more detail the essentials of the myth, Eurystheus the king of Mycenae ordered Hēraklēs to clear an immeasurable accumulation of manure produced by countless cattle in stables belonging to Augeias, the king of Elis. In terms of the myth as we see it being retold in the visual narrative of the metopes built into the Temple of Zeus, this deed of Hēraklēs, his removal of manure, was the twelfth and last of the hero’s Labors, represented in the twelfth and last of the twelve metopes gracing the temple.

§4. By contrast, in terms of the myth as retold by “Apollodorus” (again, 2.5.5), this deed of Hēraklēs, removing manure from the Stables of Augeias, is not Labor 12 but Labor 5, and the retelling makes it clear that this particular Labor was actually invalidated by the king Eurystheus—on the grounds that Hēraklēs had demanded that the king Augeias should pay wages to the hero for his labor. Similarly, as we also read in “Apollodorus” (2.5.2), Eurystheus had invalidated Labor 2, the hero’s killing of the Lernaean Hydra, on the grounds that Hēraklēs had fought the beast not alone but with the help of his nephew, Iolaos. In terms of this same version of the myth, as retold by “Apollodorus,” the Labors imposed by Eurystheus on Hēraklēs were originally ten, not twelve, and it was only because Labors 2 and 5 were invalidated that Labors 11 and 12 were added, centering respectively on the Apples of the Hesperides and on Cerberus the Hound of Hādēs. So we read in “Apollodorus” (2.5.11 and 2.5.12).

§5. The invalidation, by the king Eurystheus, of Labor 5 in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (again,2.5.5; pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I) is of particular interest. I will explain, in terms I developed in the Excursus of Essay 5. To start, our very first impression may well be that the invalidation of this Labor makes no sense—at least, it seems to make no sense to us from a purely synchronic point of view. Why should it matter, if Hēraklēs is to be paid or not paid any wages in compensation for labor performed in the service of a king? But it does matter—from a diachronic point of view. And that is because the labor that the hero is performing here is in the service of the king Eurystheus, not the king Augeias. If the hero Hēraklēs had been exclusively in the service of the king Augeias when he was shoveling out the manure from the Stables of that king, he could have demanded compensation. But he must perform this Labor gratis, not for payment, because he is really in the service of the king Eurystheus. It was Eurystheus, not Augeias, who had given the orders to our Strong Man. Here again I apply terminology developed in the Excursus of Essay 5: as we forward-reconstruct the model of “Strong Man in the service of King,” the Strong Man must obey the king’s orders, no matter what, since these orders are divinely authorized. If the Strong Man does not obey, it is a “sin.” In Essay 4 §§18–19, I have already pointed to the reconstructions of Georges Dumézil concerning various such mythologized “sins” committed by a generic Strong Man in the service of a generic King.

§6. The Labors of Hēraklēs are ordered by the king Eurystheus, yes, but the orders of this king are authorized by Zeus. These orders, these commands, can be quite arbitrary, but the authorization is purposeful. When Hēraklēs is commanded to shovel the immeasurable accumulation of manure produced by countless cattle—and that is what we see him actually doing at Metope 12 while his divine patroness Athena is sternly looking on—his choice to go ahead and shovel can count as a Labor only if he accepts the authorization of Zeus. If he accepts—I say it one more time here—he must perform the Labor gratis, not for payment.

§7. To apply again the terminology I developed in the Excursus of Essay 5, I am arguing that it is irrelevant, from a synchronic point of view, that Augeias, in the story as retold by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; again, pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), refuses to pay wages to Hēraklēs after the hero’s work is done. But it is relevant for Hēraklēs from a diachronic point of view—if the deed that he performs in this case is not a Labor but a sub-Labor, which is what the Labor becomes, a sub-Labor, because it is invalidated by the king Eurystheus.

§8. This sub-Labor, on the other hand, is still a Labor for the king Augeias. When Augeias devalues, by way of non-payment, the work of Hēraklēs, this king is acting without the authorization of Zeus. In terms of the myth as visually retold in Metope 12 of the Temple of Zeus at Olympia, which as we saw was commissioned by the state of Elis in the mid-fifth century BCE, the Labor performed by Hēraklēs for the king of Elis in the heroic age is relevant to the local traditions of Elis in the post-heroic age. In terms of the myth that is being retold in Metope 12 of the Temple of Zeus, which is based on mythology that is evidently meant to validate the state of Elis, the Strong Man will take revenge on a king who has acted in bad faith and who thus becomes polluted. In the version of the myth as reported by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; again, pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), the superhuman scale of the Labor performed by Hēraklēs for Augeias even magnifies the need for revenge against the polluter. In this version, as narrated by “Apollodorus,” the Strong Man had used his superhuman strength to divert the rivers Alpheus (Alpheiós) and Peneus (Pēneiós) in the direction of the Stables, thus washing away the polluting accumulation of manure. But Hēraklēs is denied remuneration in this narrative—despite the support of a prince of Elis named Phyleus, who was a son of Augeias. As we will soon see, the role of this prince Phyleus in the myths of Elis is relevant, since Phyleus is destined to become a future good king who will make up for the sins of the bad king Augeias, his father. But such a destiny for Phyleus is still on hold. For now, in the narrative of “Apollodorus,” the king Augeias continues to deny remuneration for the hero Hēraklēs, and, most contemptuously, he dismisses from his palace not only the hero but also the prince, who is his son Phyleus. And there is even more to the story: after Hēraklēs is dismissed by Augeias, the narrative immediately shifts to a most notable sub-Labor: Hēraklēs now goes off to a wedding feast and kills the Centaur Eurytion, who had forced the hero Dexamenos to give his daughter away to the beast. All this is happening in a very compressed retelling by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; again, pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I).

§10. And here is what I find most remarkable about this entire retelling: it is what “Apollodorus” says right after having said that Hēraklēs installed a new kingship in Elis. The very next thing that the hero does, says “Apollodorus” (again, 2.7.2; pp. 249 and 251 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), is to establish the athletic competition, agōn, of the Olympics. We see here an explicit correlation of this athletic festival with the very idea of sovereignty. And it is most relevant here to note the political motive, documented in Essay 1 Section C, for the state of Elis to undertake the building of the Temple of Zeus in the mid-fifth century BCE: the creation of this temple by this state was a grand way of celebrating the fact that Elis had taken control of Olympia and the Olympics a few decades earlier. So, the myth that was retold in the Twelfth Metope of the Temple, which was the Twelfth Labor of Hēraklēs, could be seen as a primal event that had set off a chain of further events that resulted not only in the founding of the Olympics by Hëraklēs in the heroic age but also in the re-founding of this festival by the state of Elis in the post-heroic age—now that Elis had taken away control of Olympia and the Olympics from Pisa, just as Hëraklēs had taken away control of Elis from the bad king Augeias and given it to the good king Phyleus.

§11. In this context, however, I need to emphasize that my intent is not to underrate the mythological significance of the king Augeias. Even if he is a negative model of kingship, since he is pictured as a bad king, he is nevertheless a good fit for an “Indo-European” pattern of stories about a Strong Man in the service of a King. In such stories, there are multiple opportunities for “sinning” to be committed by the King, not only by the Strong Man. I should add that the significance of the role of Augeias in the myth about the Stables is so old as to be Indo-European. After all, the name of this king Augeias, like the name of the hero Hēraklēs, even has an Indo-European etymology, as I have argued in earlier work (Nagy 1979/1999:174–175 at 15§9). The Homeric name of Augeas/Augeias, which is Augeíās (as in Iliad 11.701), can be analyzed as the Ionic reflex of *Augā́ās (by way of *Augḗās), derivative of a noun that survives as augḗ, referring to ‘sunlight’. And it may be relevant that Augeias was the son of the Sun according a myth mentioned in passing by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5). Similarly, as I have also argued in earlier work (again, Nagy 1979/1999:174–175 at 15§9), the Homeric name of Aeneas/Aineias, which is Aineíās, can be explained as the Ionic reflex of *Ainā́ās (by way of *Ainḗās), derivative of a noun that survives as aínē ‘praise’ (so Herodotus 3.74, 8.112), which is a by-form of aînos, again in the sense of ‘praise’. On Aeneas as a royal personality, I refer to my comments introducing Rhapsody 20 of Iliad 20 in my Homeric commentary. As I say there, “By virtue of being the son of Aphrodite/Venus, Aeneas possesses a genealogical and dynastic charisma that threatens to overshadow the purely epic charisma of his Iliadic opponent Achilles.”

§12. Having noted an Indo-European phase in the roles played, as it were, by the king Augeias and the hero Hēraklēs, I now introduce two subsequent phases, Mycenaean and post-Mycenaean. A forward-reconstruction of these two phases will be a useful way of tracking the various different myths about the Labors and the so-called sub-Labors of Hēraklēs. And I focus again on the relevance of the narrative by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; 2.7.2). As we have seen, the failure of Augeias, king of Elis, to compensate for the clearing of his stables by Hēraklēs results in a war waged by our hero against that king, and this war is brought to an end only after Augeias is defeated and killed by Hēraklēs, who then installs the king’s son Phyleus as the new ruler of Elis. Further, Hēraklēs then follows up by establishing the athletic festival of the Olympics at Olympia (“Apollodorus” 2.7.2, pp. 249 and 251 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I). It is this follow-up, accomplished by Hēraklēs, that I highlight again, arguing that such a sequence of events—where the hero (1) establishes a new kingdom and then, right after that, (2) establishes an athletic festival as the centerpiece of that kingdom—amounts to a myth that is meant to explain the origins of some form of sovereignty. And such sovereignty could be linked not only with the glory days of the Mycenaean Empire but also with a post-Mycenaean era that came thereafter.

§13. Relevant here is a detail that I have already noted in the overall story of Hēraklēs as retold by Diodorus of Sicily (4.14.2), where we read that Hēraklēs not only established the athletic festival of the Olympics but also competed and won in every athletic event. An earlier version of such a story comes to life in an ancient painting that shows Hēraklēs wearing on his head the olive garland that marks the sum total of his Olympic victories. As we will see in the analysis that follows, these athletic victories of Hēraklēs exemplify the emergence of new dynasties that were destined to dominate the overall region of the Peloponnesus in a post-Mycenaean age.

§14. The myth that tells about the defeat of Augeias, king of Elis, by the hero Hēraklēs is also told in a victory ode of Pindar, Olympian 10, composed for the celebration of an athlete’s victory at the Olympics in 476 BCE. I have already noted in Essay 1 Section C the relevance of this song of Pindar to myths about Olympia as the site of the Olympics. And now we learn from the wording of Olympian 10 a vitally important additional detail: it turns out that the royal wealth of Augeias, plundered by Hēraklēs in the course of his wartime victory over the king, became the funding, as it were, for the founding of the Olympics (lines 55–59). This ode of Pindar, composed decades before the state of Elis completed, in the mid-fifth century, its project of building the Temple of Zeus in Olympia, already anticipates the reason for the prioritizing, by the state of Elis, of one of the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs as the twelfth and culminating deed of the hero in the set of relief sculptures gracing the twelve metopes of the Temple. According to the logic built into the myth about the Twelve Labors of Hēraklēs as retold in the twelve metopes, it is this one Labor, the clearing of the stables, that required a compensation achieved in the form of plundered wealth. And the wealth was used to fund, in terms of the myth, the founding of the Olympics. Further, again in terms of the myth, the compensation for this Labor included not only the Olympics as an eternally lasting athletic festival but also the building of the Temple of Zeus, metopes and all, as the sacred centerpiece of that festival.

§15. By contrast with such a scenario for mythologizing the foundation of the Olympics, I see traces of an earlier scenario in another version of the myth—this time, as retold by Pausanias, who, like “Apollodorus,” is another source who is dated to the second century CE. We read the following details in the retelling by Pausanias (5.3.1):

Hēraklēs, evidently in revenge for not having been compensated by Augeias for the clearing of the Stables, ultimately defeated this king of Elis in war, having recruited an army from Argos, Thebes, and Arcadia.

Although Hēraklēs succeeded in capturing Elis, plundering its wealth, he did not kill Augeias; instead, he simply installed Phyleus, son of Augeias, as the new king of Elis.

Although Hēraklēs captured and plundered Elis, he spared another city, Pisa, from being overrun by his armed forces, even though this city was an ‘ally’ of Elis

Hēraklēs spared Pisa because the Oracle of Apollo at Delphi told him that Pisa was of special concern to the father of Hēraklēs—that is, to Zeus: πατρὶ μέλει Πίσης ‘[his] father cares about Pisa’.

§16. By hindsight, the last detail I have listed here, about the sparing of Pisa by Hēraklēs, implies an earlier version of the myth—a version that seems relatively unfavorable to Elis and favorable to Pisa. But the harsh reality, as I noted in Essay 1 Section C, is that the state of Pisa was eventually destroyed, as an independent power, by the rival state of Elis; Pausanias himself says so, in passing, at 6.22.4. And, as I also noted in Essay 1 Section C, Elis had already at an earlier time—in the fifth century BCE—annexed Pisa and taken control of Olympia and the Olympics. This takeover, as I also noted in Essay 1 Section C, happened well before the final destruction of Pisa, which happened some time after 364 BCE. As for the earlier time, when Elis (1) annexed Pisa and (2) took control of Olympia and the Olympics in the fifth century BCE, these two events preceded the actual building of the temple of Zeus in Olympia later on in fifth century BCE. The building of that temple, we know for a fact, was of course the project of Elis, not of Pisa.

§17. The ultimate destruction of Pisa by Elis was so radical, I must add, than even the precise location of Pisa is currently unknown—as I showed in Essay 1 Section C. And, as I also showed there, it is doubtful that the state of Pisa in its heyday was ever even a pólis in the sense of a centralized city-state, although there is evidence for an episodic form of statehood for Pisa many years later, in the fourth century BCE (documentation by Hansen and Nielsen 2004:500–501). By contrast, however, we do know for sure that the state of Elis, which won out over the state of Pisa, eventually became a pólis—precisely in the sense of a centralized city-state. It happened, as I noted in Essay 1 Section C , at a relatively late point in the history of Elis, that is, in the early fifth century BCE. In this context, I find it relevant that Hēraklēs, in myth, deposes Augeias as king of Elis and installs as the new king a prince who is son of the old king, and that this prince, as we have already seen in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (2.7.2; pp. 249 and 251 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), and, earlier, of Diodorus (4.33.3–4), is actually named Phyleus, Phūleús. The name is evidently derived from the noun phūlḗ, which is often mistranslated as ‘tribe’ but which refers, as I have argued in a different work (Nagy 1990b:277), to a subdivision of a pólis or ‘city’, as in the case of the traditional three- or four-phūlaí systems of most Dorian cities. And I find it also relevant that the state of Elis, in the process of evolving into a full-fledged pólis, was reorganized as a city-state that consisted of eight phūlaí, as we learn for example from Pausanias himself (5.16.7, commentary in Nagy 1990a:365–366 at 12§52). To put it another way, the eight phūlaí of Elis were the building-blocks of its new status as a full-fledged pólis or ‘city-state’. By contrast, Elis prevented Pisa from continuing to exist as the old city that once hosted the Olympics.

§18. Despite the displacement of Pisa by Elis as host of the Olympics, however, Pausanias records myths that reflect earlier realities, when Elis had not yet controlled the Olympics. Moreover, in the narrative of Pausanias, he takes even further back in time the myths about the Olympics—back to times that predate the era of Hēraklēs, son of Zeus. In the myths about the Olympics as retold by Pausanias (5.8.3), Hēraklēs the son of Zeus was not even the founder of this festival: he only presided over one particular celebration of the Olympics, and even this presidency happened only after he had deposed Augeias as king of Elis by defeating him in war; before the war, according to this version of the myth, it had been the king Augeias who had presided over the Olympics (again 5.8.3). Moreover, even before Augeias, as we also read in Pausanias (5.7.10–5.8.2), earlier heroes had likewise presided over the Olympics. In the inventory that follows, I list in chronological order, going forward in time from the earliest to the latest phases of the mythologized Olympics, all the presidents listed by Pausanias:

—A First Hēraklēs, who originated from Mount Ida in Crete (Pausanias 5.7.6–7).

—Klymenos, who also originated from Crete and who was descended from the First Hēraklēs, to whom he set up an altar at Olympia, so that this First Hēraklēs could thereafter be worshipped as the parastatēs ‘the one who stands by’ (Pausanias 5.8.1).

—Endymion son of Aethlios son of Aiolos—or, alternatively, Aethlios was son of Zeus (Pausanias 5.8.2).

—Pelops (Pausanias 5.8.2).

—Amythaon, son of Kretheus son of Aiolos (Pausanias 5.8.2).

—Pelias and Neleus, twin brothers presiding together (Pausanias 5.8.1); as we read elsewhere (Pausanias 4.2.5), Pelias and Neleus were sons of Kretheus son of Aiolos; or, alternatively, as Pausanias also reports (again 4.2.5), Pelias and Neleus were sons of Poseidon (this alternative version is affirmed elsewhere as well: Odyssey 11.254)

—Augeias (Pausanias 5.8.3)

—Hēraklēs (Pausanias 5.8.3).

§19. What I find especially remarkable about this reportage of Pausanias is that he is faithfully narrating myths that he himself does not accept, since we know, as I showed in Essay 1 Section C, that he accepts, instead, the idea that the date of inception for the Olympics was 776 BCE. To be contrasted is the reportage of Strabo, 8.3.30 C355, who likewise accepts the same date of inception but who then, on that basis, refuses even to entertain the very idea that the Olympics had been founded by mythological figures like Hēraklēs the son of Zeus—let alone a far more remote figure like the so-called First Hēraklēs.

§20. This refusal on the part of Strabo is at first sight quite understandable, since the myths about Olympic founders as reported by our later source, Pausanias, are so blatantly full of mutual contradictions. To cite the most notorious example, I come back to the First Hēraklēs. In the light of the skepticism expressed by a source like Strabo, we too may well ask ourselves: who on earth was such a First Hēraklēs? As I will now argue, however, an answer can be found by way of analyzing those same contradictions that are built into various different myths about different heroes named Hēraklēs and about other such heroes. The contradictions, as we will see, reveal different phases in the evolution of different myths.

§21. For example, in the myth about a First Hēraklēs as we see it retold by Pausanias (again, 5.7.6–7), I note the following points that I find particularly valuable for comparative analysis:

– The First Hēraklēs competed in the very first Olympics. He and his brothers, all five of them, competed with each other in the form of improvised athleticism, and Hēraklēs emerged victorious by engaging in a primordial footrace. This earlier Hēraklēs, as we also read in Pausanias (5.7.7), improvised, as a prize for such an athletic victory, the awarding of an olive garland.

– The First Hēraklēs and his brothers were five in number and were therefore called the ‘Dactyls’ or ‘Fingers’—in the sense that the Greek noun dáktulos means ‘finger’. Alternatively, I suggest that maybe the five of them were the five ‘Toes’ of the foot in footracing. I will have more to say in Essay 12 about the mythological implications of the foot of Hēraklēs as a standard of measure for competitios in footracing.

– Because the First Hēraklēs and his brother ‘Dactyls’ were five in number, the Olympics are celebrated on every fifth year (‘fifth’ by way of inclusive counting, since the Greek language had no zero).

– The First Hēraklēs and his fellow ‘Dactyls’ hailed from Mount Ida in Crete. I should note that the mention of Mount Ida, situated in Crete, seems to signal a local mythological variant, rivaling more familiar variants where the primal mountain linked with Hēraklēs would be Mount Olympus. I will have more to say in Essay 10.about such variations.

—So also in the case of the next known president of the Olympics after the First Hēraklēs, named Klymenos: this hero too was a Cretan by origin, as we have already seen in the reportage of Pausanias (5.8.1), who adds that this Klymenos presided over the Olympics precisely because he claimed descent from the First Hēraklēs.

§22. On the basis of the points I have made, then, I now have an answer to my own rhetorical question about the very identity of the “First Hēraklēs.” I propose that this First Hēraklēs was a Mycenaean or even Mycenaean-Minoan variation on the theme of Hēraklēs as founder of the Olympics—by contrast with a chronologically later Hēraklēs who funds the Olympics by way of plundering the royal wealth of Augeias, king of Elis. In terms of such a contrast, the later Hēraklēs would be a post-Mycenaean variant. In the myth of this later Hēraklēs as retold by Pausanias (5.8.4), the hero competed in two athletic events on the occasion of his re-founding, as it were, of the Olympics, and he emerged victorious in both competitions, which were the events of (A) wrestling and (B) pankration, a less regulated form of combat sport. But this later Hēraklēs, as we have already seen, was not the original founder of the Olympics—from the standpoint of the myth as retold by Pausanias. According to that version of the myth, it is the First Hēraklēs who qualifies as the true founder of the Olympics.

§23. I now draw a contrast between the myth of a First Hēraklēs, originating from Mount Ida in Minoan-Mycenaean Crete, and the myth of a later Hēraklēs who leads an army recruited from Argos, Thebes, and Arcadia in his successful effort to defeat Augeias, king of Elis, and to establish himself as the founder or at least the re-founder of the Olympics. In terms of the later myth, attested in the reportage of Pausanias (5.7.6–5.8.4), both the earlier and the later Hēraklēs had a role in the evolution of the athletic events that took place in the Olympics at Olympia in Elis, but it was the Minoan-Mycenaean Hēraklēs who counted as the very first competitor and winner, in the footrace known as the stadion, as distinct from the later Hēraklēs, who competed and won in the athletic events of wrestling and the pankration.

§24. But I am not claiming, I must now emphasize, that the later Hēraklēs, by contrast with a Minoan-Mycenaean Hēraklēs, is only “post-Mycenaean.” The Labor of our “later” Hēraklēs, which is the clearing of the Stables of Augeias, may be “post-Mycenaean” in some respects, but the same Labor is also distinctly Mycenaean in other respects, as we will now see.

§25. In search of Mycenaean traces, I return to the two most comprehensive and systematic ancient sources retelling the myths about the Labors of Herakles, Diodorus and “Apollodorus.” In both these sources, the clearing of the Stables of Augeias is hardly the Twelfth and thus, climactically, the last and most important of the hero’s Twelve Labors, as in the case of the version of the myth promoted by the state of Elis. Instead, this Labor is the sixth of twelve in the case of Diodorus (4.13.3) and the fifth of twelve in the case of “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; especially pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I). Also, as I have noted at §§4–5 of this essay with reference to the same passage from “Apollodorus” that I just cited (pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer), it is said that the Twelfth Labor of Hēraklēs, the clearing of the Stables of Augeias, could even be discounted as a Labor. That is, this Labor was invalidated by Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, who had given the original order for the hero to clear the Stables of Augeias, king of Elis. Thus this Labor, according to the myth as retold in “Apollodorus” (again, pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer), simply did not count. And it was discounted on the grounds that Hēraklēs had demanded that the king Augeias should pay him wages for his Labor, without telling this king that the original order for the hero to clear the stables of Augeias came not from that king but from the over-king Eurystheus. The Labor performed by Hēraklēs as work for pay on behalf of Augeias, king of Elis, was instead supposed to be performed as work for no pay on behalf of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae. Earlier in this essay, I analyzed the mythological implications of such an invalidation of this Labor of Hēraklēs, and I now recapitulate the relevant parts of that analysis in what follows here, concentrating on distinctions between Mycenaean and post-Mycenaean viewpoints.

§26. The invalidation by Eurystheus of Labor 5 in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (again, 2.5.5; pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I) is explained this way: the Labor that the hero is performing here is in the service of the king Eurystheus, not the king Augeias. If the hero Hēraklēs had been engaged exclusively in the service of the king Augeias when he was shoveling out the manure from the stables of that king, he could have demanded compensation. But he must perform this Labor gratis, not for payment, because he is really in the service of the king Eurystheus. It was Eurystheus, not Augeias, who gave the orders.

§27. The Labors of Hēraklēs are ordered by the king Eurystheus, but the orders of this king are authorized by Zeus. I epitomize here my formulation from §6. These orders, these commands, can be quite arbitrary, but the authorization is purposeful. When Hēraklēs is commanded to shovel the immeasurable accumulation of manure produced by countless cattle—and that is what we see him actually doing in Metope 12—his choice to go ahead and shovel can count as a Labor only if he accepts the authorization of Zeus. If he accepts, he must perform the Labor gratis, not for payment.

§28. In the myth as retold by “Apollodorus” (2.5.5; again, pp. 195 and 197 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), Augeias the king of Elis refuses to compensate Hēraklēs for the Labor of clearing his royal stables only after he finds out that it was Eurystheus the king of Mycenae who had given the original order for this Labor. And it is only after Eurystheus finds out that Hēraklēs had demanded that Augeias the king of Elis should compensate him for his Labor that this over-king of the Mycenaean Empire refuses to count this Labor as a Labor.

§29. But how could Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, find out that Hēraklēs had demanded compensation from Augeias, king of Elis, for the Labor of clearing that king’s stables? To me it is evident that the informant must have been a character named Kopreus, son of Pelops. This Kopreus is described in Iliad 15.639–640 as a messenger of Eurystheus, and, in his capacity as a royal delegate, he is put in charge of informing Hēraklēs about all the various Labors that the king of Mycenae orders the hero to perform. His name, Kopreús, turns out to be a “talking name” in the context of the Labor that requires Hēraklēs to clear the kópros or ‘manure’ from the stables of Augeias—the word kópros is actually used by Diodorus (4.13.3) with reference to this Labor. In the context of this myth, then, Kopreús is literally ‘the man connected with the manure’. Further, in the corresponding narrative of “Apollodorus” (2.5.1 p. 187 ed. Frazer 1921 I), we learn that this man Kopreus, son of the hero Pelops of Elis, became the official kērux ‘herald’ of king Eurystheus in Mycenae after having been exiled from his native Elis, and that it was in this capacity, as a herald, that Kopreus delivered to Hēraklēs the various orders for the hero to perform his various âthloi ‘Labors’. Since Kopreus is an adoptive Mycenaean, there is a logic to the fact that his son Periphetes, who gets killed in the Iliad (15.638–643), is actually described there as one of the Mukēnaîoi ‘Mycenaeans’ (lines 638 and 643).

§30. The mythological details about this Kopreus reveal both Mycenaean and post-Mycenaean aspects of the myth about the Labors of Hēraklēs. Only in the context of Elis, where the Labor of Hēraklēs requires the removal of manure from the stables of the king Augeias, is the relevant name Kopreús mythologically connected with the idea of manure. In other contexts, there seems to be no such mythological connection. And, as we read in the scholia for Iliad 23.346–347, there is another character in Greek myth who has this very same name, Kopreús—he is king of Haliartos in Boeotia—and, again, we find in such a case no mythological connectivity with the idea of manure.

§31. Here the evidence of the Greek language as attested in the Linear B texts of the Mycenaean era proves to be decisive. The personal name Kopreús is actually attested in these texts: it is spelled ko-pe-re-u (Knossos Am 821; Pylos Es 646 and Es 650). But this form cannot mean ‘man connected with manure’, since such a form in Linear B would be spelled *ko-qe-re-u, representing *kokʷreús, not kopreús. The Greek noun kópros ‘manure’ has to be reconstructed as *kokʷros not *kopros, as we know from comparative evidence: there is a cognate noun in Sanskrit with the same meaning ‘manure’, śákṛt, śaknáḥ, which must likewise be derived from a root shaped *kokʷ-, not *kop-. So, as the noted Indo-Europeanist Charles de Lamberterie (2012:490–497) has argued most effectively, the Mycenaean name Kopreús has nothing to do with manure, and can best be etymologized as a derivative from the verb kóptein in the sense of ‘cut’ or ‘strike’.

§32. But this is not to say that the name Kopreús in the first millennium BCE cannot be understood as meaning ‘man connected with the manure’, since the distinction between kʷ and p, still maintained in the second millennium BCE, that is, in the Mycenaean era, had by now been lost in the post-Mycenaean era of the first millennium: now there is only p as in Kopreús. In this post-Mycenaean era, a mythological character by the name of Kopreús could thus be readily linked with the myth about the kópros ‘manure’ that had to be cleared by Hēraklēs from the stables of Augeias. In terms of Greek morphology, Kopreús in the first millennium BCE would be understood as a derivative of kópros ‘manure’. As we see from the linguistic analysis of de Lamberterie (2012:496), there are ample examples of such a derivational pattern (Τοξεύς as derived from τόξον, ῾Οπλέυς as derived from ὅπλον, and so on).

§33. But the myth that tells how Hēraklēs shoveled away the kópros ‘manure’ from the stables of Augeias could have existed even without the existence of a messenger from Mycenae by the name of Kopreús. In other words, such a myth could have existed already in the Mycenaean era. After all, the fertilizing of soil with the manure of cattle is associated with rituals that are ancient enough to be dated back to the second millennium BCE. Evidence for such rituals can be found in wording that we read in sacred laws prohibiting the removal of kópros ‘manure’ from soil that is deemed to be sacred. I cite an example from Supplementum Epigraphicum Graecum 28:100 line 2, [ἐκ] τᾶς ἱερᾶς γᾶς κόπρον μὴ ἄγεν μηδεμίαν ‘not to take [agein] any manure [kópros] out from the sacred [hierā] land’. It is in the light of such contextual evidence that we can come to terms with the semantics involved in the ancient place-name Kópros (mentioned in the scholia for Aristophanes Knights 899). We see here the actual name of one of the demes [dêmoi] of Attica (that is, of the overall region controlled by Athens). And, as in the case of official Athenian references to any demesman native to any deme of Attica, the designation of a demesman who is native to the deme of Kópros is actually Kóprios, as we read for example in the wording of an Athenian decree quoted by Demosthenes (18.73: Εὔβουλος Μνησιθέου Κόπριος εἶπεν).

§34. I conclude, then, that the mythological appropriation of a character named Kopreús, by way of a story that tells about his relocation from his native Elis to his adoptive home in Mycenae, can be seen as symbolic of a powerfully prestigious tradition that connects the post-Mycenaean heroic world with its all too distant Mycenaean past. Such a connection, even if it is etymologically incorrect from the standpoint of this past, is etymologically correct from the standpoint of the first millennium BCE, when the name Kopreús, referring to the herald of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, can be understood to mean ‘the man connected with the manure’. After all, this same Mycenaean herald is connected with all twelve of the Labors of Hēraklēs, and one of those Labors—the Twelfth and most important of the Twelve according to the local myths of Elis—is in fact the clearing of the kópros ‘manure’ from the stables of Augeias, king of Elis.