2022.08.01 | By Gregory Nagy

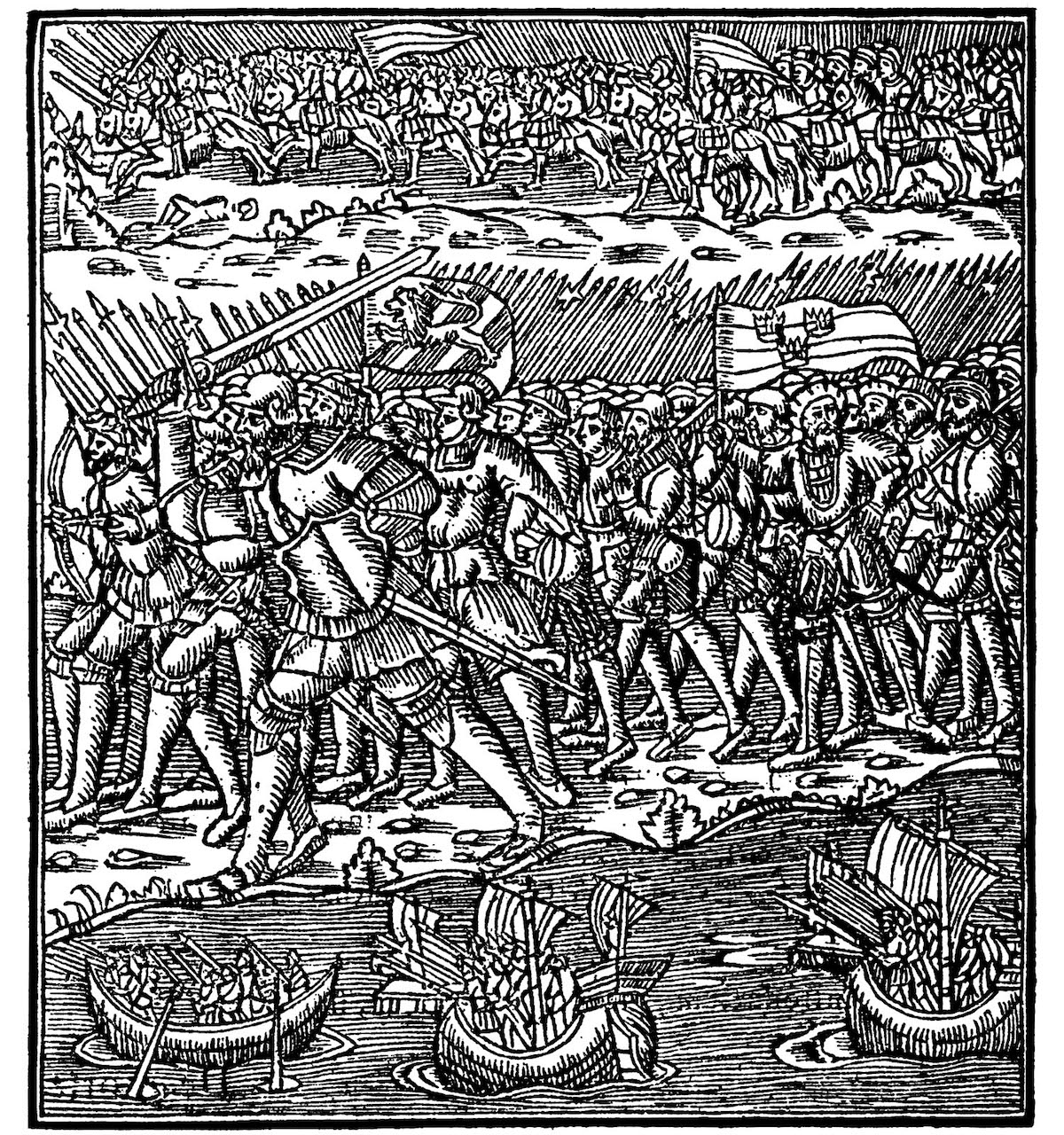

§0. In Essay 6, we have seen that Hēraklēs, as an athlete, demonstrates his role as a culture hero of civilization. His very first Labor, the killing of the Nemean Lion, is a shining example, since the choke-hold that Hēraklēs applies to the beast in killing it exemplifies his athleticism as a champion of an athletic event known as the pankration. And, as we can see from my overall survey of the Labors and the sub-Labors of Hēraklēs in Essay 4, most of these feats performed by the hero can be seen in terms of his prowess as a Strong Man who is acting alone—acting as an idealized example for his people to follow. Here in Essay 7, however, I will consider two myths where the feats of Hēraklēs seem to be different. In the first myth, as we will see, the hero is acting together with a large group, as their leader. In the second myth as well, the hero is figured as a leader—even if he seems at first to be acting quite alone. For analyzing both myths, I will apply in this essay an explanatory model that I will define as prototyping. And, for illustrating what I mean, I have chosen an image that I think is most relevant. We see here a picturing of a Strong Man as the leader of a large grouping of people. But the leader is in this case not Hēraklēs, the quintessential Strong Man of the ancient Greeks, but rather an Indo-European “cognate” Strong Man stemming from medieval Germanic traditions. That other leader is Starkaðr, and the old carved image that we see here pictures him in the heroic role of leading into battle the combined armed forces of Sweden, both army and navy.

§1. Before I attempt my definition of prototyping, I offer a preliminary sketch of the two Greek myths that I have selected for analysis. Both myths are most clearly attested in retellings by Diodorus of Sicily, who as we have seen is dated to the first century BCE. In the first myth, as we read in Diodorus (4.17.1–4.18.2), Hēraklēs in his quest to raid the cattle of Geryon became the leader of a mighty army combined with an equally mighty navy. As for the second myth, I have already highlighted it in Essay 5: we read, again in Diodorus (4.14.1–2), that Hēraklēs was not only the founder of the Olympic Festival but was also a competitor in every athletic event of the first Olympics, and, even more, that he was the victor in each one of these events; Diodorus mentions, as specific examples, the athletic events of (1) competing in the stadion-length footrace, (2) competing in a wrestling match, and (3) competing in the pankration, which as we have seen was a combat sport that combined elements of both wrestling and boxing. In Essay 5, I have already referred to this myth about the founding of the Olympics by Hēraklēs and about his competing in all the athletic events—but without yet saying how the hero actually became the victor in all these competitions. According to the myth as reported in Diodorus (again, 4.14.1–2), Hēraklēs was the victor in all the competitions of the first Olympics because all the other competitors recognized this hero as the only possible victor. The obvious paradox here is that Hēraklēs wins in a footrace where he has no one to race against and in two one-on-one combat matches where he has no one to fight against.

§2. I have analyzed such a mentality in an earlier work, Nagy 2015.04.24, and in the book Masterpieces of Metonymy (Nagy 2016|2015, 3§14), where I highlight the logic, in myth, of do as I do. For example, as I argued in the essay and in the book that I just cited, divinities can show their worshippers how to worship them by acting as models for the act of worshipping. (This formulation goes back to Nagy 1996a:57, referring to an earlier version of what became an influential book, Patton 2009.)

§3. This paradox, where the gods can be represented in the act of worshipping and can thus become models of worship by showing you how to worship them even though these gods themselves have no one to worship, is comparable to the paradox we have seen in the myth about the founding of the Olympics by the hero Hēraklēs: in this case, the hero can be represented in the act of competing in the athletic events of the very first Olympics and can thus become a model of athletic competition even though Hēraklēs himself had no one to compete against—at least, not on the prototypical occasion.

§4. I am now ready to apply the model of prototyping to the obvious paradox we see in the myth about Hēraklēs as athlete—and also to a not-so-obvious paradox that I hope to highlight in the myth about Hēraklēs as a warrior who leads other warriors. Here the same hero, pictured as leading a vast army and navy, seems in the end to be the one person who has done all the fighting, doing it all by himself, all alone.

§5. That said about the two myths I am considering, I now proceed to my working definition of prototyping. I cannot say that the word has never been used before by anyone, but, in any case, I offer here a new way of using it. Let me say, then, that prototyping is the making of one prototype out of many types of persons or things—even if such types stem from various different times, various different places. Myth can do that: it can make a prototype out of whatever is observed in and by myth. And there may be many varieties of what is observed, but myth will nevertheless be able to retrofit all variations into a singular unity, as if all the observable variants could get traced back and thus get somehow explained, in a unified way, as one unique original.

§6. Such prototyping is what happens to Hēraklēs as he is observed in and by the various different surviving Greek myths that tell about his Labors and his “sub-Labors.” In these myths, Hēraklēs can come across as one and the same person, even if he may have various different roles to play in various different tellings of the myths. And that is because such differences in roles can get leveled out and smoothed over.

§7. The leveling-out and the smoothing-over of differences in the various different roles of Hēraklēs in various different tellings of myths about this hero can lead not only to a sense of uniqueness but even to a kind of certainty about absolute uniqueness. And if Hēraklēs becomes, in the course of time, an absolutely unique warrior or athlete, then he can also become an absolute model for other warriors and athletes.

§8. Thus in the case of myths about Hēraklēs as a Strong Man who leads a mighty army combined with an equally mighty navy, he leads all other warriors by example because he is the absolute and therefore unique example for these warriors. The way that Hēraklēs fights the enemy and faces death is the absolute model for all other warriors, and thus the story of the hero can become the story of all warriors. So, there is no need for myth to highlight the actions of any warrior other than the hero Hēraklēs whenever myth points its camera, as it were, at this hero’s involvement in any action of battle by land or sea. That is why, other than the explicit mention of the mighty army and navy that is led by Hēraklēs, there is no mention of any feats performed by any of the warriors that are being led by the hero in this myth as retold by Diodorus (again, 4.17.1–4.18.2). The Strong Man is not only in the foreground: he is also the foreground itself. To say it another way, the Strong Man becomes the defining foreground for any story that involves him. And “the cast of thousands” (to speak Hollywood-speak) who follow the Strong Man’s leadership will become merely the background of the story-telling—as we saw also in the wood-carving that pictures the Scandinavian Strong Man Starkaðr in the forefront as he leads the Swedes to battle the Danes. Even the king of the Swedes, marked by his insignia picturing the Three Crowns, is placed behind, not in front of, the pugil Sueticus or ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’, who is in turn marked by insignia picturing the rampant Lion. I have already commented on the relevant symbolism in Essay 5.

§9. Just as the medieval Germanic Strong Man Starkaðr, as a leader of warriors, can be pictured as an idealized athlete—as ‘the fist-fighter of Sweden’—so also the ancient Greek Strong Man Hēraklēs is a model of leadership in athletics, not only in war. He is the perfect athlete who, in demonstrating his athletic perfection, becomes the founder of the ancient Olympics. That said, however, the fact remains: even as a leader of men, Hēraklēs is a loner. He is a model for acting alone, a prototype of a loner in both war and athletics. As a warrior, he ordinarily acts alone as he single-handedly kills enemies, either one-on-one or one-against-many. Likewise as a hunter, he can single-handedly kill beasts with weapons, the same way that humans kill other humans in war, or he can show his athletic side by taking on the role of a Master of Animals who wrestles the beasts to death; alternatively, the Master can “bring them back alive.” And of course our Strong Man can also wrestle to death his human adversaries, like the ogre Antaios, not only beasts like the Nemean Lion. In any case, when all is said and done, Hēraklēs does it all alone—as a rule. And the two exceptions that I have analyzed here can serve to prove the rule, which is this: precisely because this hero acts alone, he can be prototyped as a superhuman who can overcome any and all obstacles to victory.