2022.07.25 | By Gregory Nagy

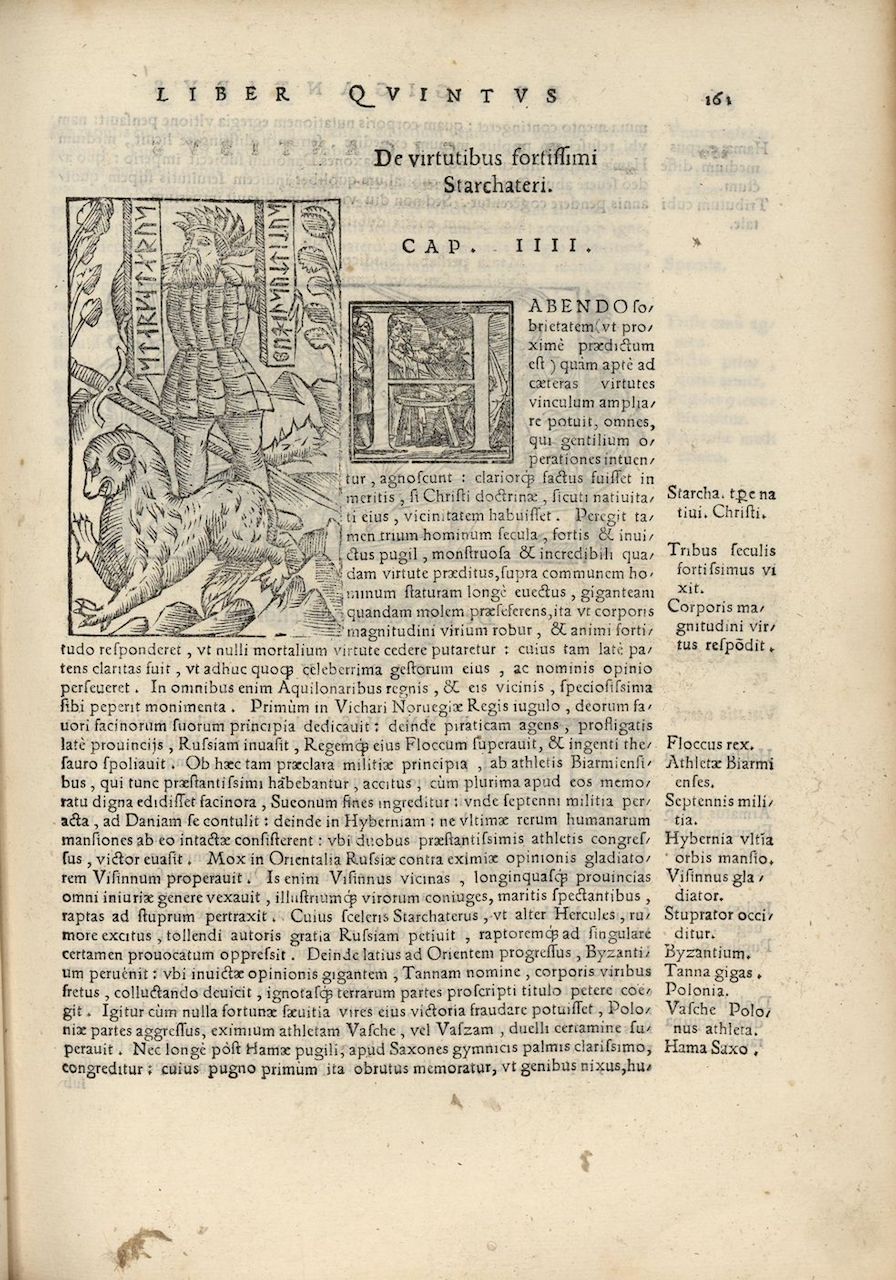

§0. Applying methods of reconstruction as I outlined them in the Excursus of Essay 5, I will now start to reconstruct what I have described as Indo-European mythological traditions that shaped the role of Hēraklēs as an athlete, or, to say it better, the role of this hero as a model for athletes. And I will return to my initially superficial comments in Essay 2 about Hēraklēs in the role of a free-style wrestler, as I described him there. In my reconstruction, I will be arguing that the Greek hero Hēraklēs in the role of an athlete is most tellingly comparable to a Germanic hero in Old Norse traditions. He is Starkaðr, and his Old Norse name means, roughly, ‘Strong Man’. And the athleticism of these two heroes I am comparing, one Greek and one Germanic, will involve not only wrestling but also boxing, that is, fist-fighting. Relevant is the image I show to introduce this essay: it is a close-up of an illustration featured on a map produced by Olaus Magnus, Carta marina et descriptio septentrionalium terrarum, first published in 1539, picturing our Norse Strong Man holding two rune staffs: as we can see, the staff in his right hand reads, in runic letters, STARCATERVS (Starcatherus), and the staff in his left hand reads PVGIL SVETICVS (pugil Sueticus), to be translated as ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’.

Detail of Carta marina et descriptio septentrionalium terrarum (1539). Olaus Magnus (1490–1557). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

§1. For now my primary task will be to reconstruct the mythological traditions that generated the role of the Germanic hero Starkaðr as ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’ and the genealogically comparable role of the Greek hero Hēraklēs as a boxer as well as a wrestler.

§2. I start with comparative evidence, assembled by Georges Dumézil (1971:25–124), connecting in general the Greek hero Hēraklēs in Greek myths with the Germanic hero Starkaðr in Scandinavian myths recorded in Old Norse texts, often mediated by medieval Latin paraphrases. With regard to the Greek and the Old Norse evidence, Dumézil had succeeded in proving that the myths about these two heroes Hēraklēs and Starkaðr are cognate in a vast variety of details. Some of these details have been analyzed further in an article by Olga M. Davidson (1980) and in the book Comparative Mythology by Jaan Puhvel (1989, especially pp. 249–255).

§3. For now, however, I concentrate on only one special aspect of the cognate heritage of myths about Hēraklēs and Starkaðr—an aspect that has I think not been noticed before. It has to do with the athleticism, as it were, of both these heroes. Such athleticism, as we will see, is linked with the roles of these heroes as guardians of the civilized world.

§3a. As I observed already at the beginning of Essay 6 here, I had considered in Essay 2 a myth centering on the athleticism of Hēraklēs in the role of a free-style wrestler—a role that is linked to his role as guardian of a civilized Greek world, but now I turn to a comparable role of his—as a free-style boxer. In the scholia for Plato’s Phaedo 89c we read about a myth, mediated by Duris of Samos (FGH 76 F 93 [= DFGH F 76]; also to be considered is Pherecydes FGH 3 F 79a [= DFGH F 368]), telling how Hēraklēs, after having founded the athletic contests at the festival of the Olympics at Olympia and having won in every one of these athletic contests on the first occasion of the festival, failed to win on the occasion of the second Olympics, four years later, in the athletic event of boxing, since his opponents at this event were now two athletes rather than one. For the record: the names given to the two victorious athletes in this report are Elatos and Pherandros. So the story goes. Thus even Hēraklēs, as the saying transmitted by Plato has it, cannot win when the contest is two-against-one. That saying is what we read in Plato’s Phaedo 89c, where we see a fleeting allusion to the relevant myth about that primordial Olympic boxing match between Hēraklēs on one side and, on the other side, Elatos and Pherandros.

§3b. At this point, I return to the image I showed at the beginning of the essay: as I already noted there, this image was featured on a map produced by Olaus Magnus, first published in 1539, where we see Starkaðr holding two rune staffs—and where the staff in his right hand reads, in runic letters, STARCATERVS (Starcatherus), while the staff in his left hand reads PVGIL SVETICVS (pugil Sueticus), to be translated as ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’. Thanks to the expert guidance of my colleague and friend Stephen Mitchell, I can now add that this picture, and the description of Starkaðr as a ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’, matches a narrative found in another work of Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, published in 1555. The text of that narrative starts off at p. 161 with an illustration in the form of a woodcut that reproduces the picture of ‘Starcatherus’ as found in the map of Olaus Magnus, and the narrative that follows actually explains at pp. 161–162 why Starkaðr gets to be described as a boxer. This narrative at pp. 161–162 corresponds to an earlier narrative recorded by Saxo Grammaticus, who lived in the late 12th and early 13th centuries CE, in his Gesta Danorum, first printed in 1514. The corresponding narrative of Saxo Grammaticus, to be found in Gesta Danorum 6.5.17–18, is probably at least in part the source for the later narrative of Olaus. We read in these two narratives that the Danes were once upon a time at war with the Saxons, who persuaded a youthful champion named Hama to fight in a one-on-one duel with an aging Starcatherus, who would be representing all by himself the king of the Danes together with the king’s entire army. The Saxon Hama, showing his overconfidence, preferred to start fighting with his hands, not with weapons, and, in this context, he is actually described by Olaus at p. 161 as a pugil ‘fist-fighter’. Then, true to form, Hama punches Starcatherus so violently with his pugnus ‘fist’ that the old hero falls down. But Starcatherus picks himself up and now gains the upper hand. In the end, Starcatherus kills Hama by cleaving the young champion in half with a single blow of the sword. Thus the Saxons are defeated, and they are now subjugated en masse by the Danes. So goes the story.

§3c. Here is the relevant text in the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (5.16–17, ed. Friis-Jensen 2015):

5.16. Interea Saxones defectionem moliri idque maxime in animo habere coeperunt, qualiter inuictum bello Frothonem preter publici conflictus morem opprimerent. Quod optime duello gerendum rati mittunt, qui regem ex prouocatione lacesserent, scientes eum discrimen omne prompta semper mente complecti, animique eius magnitudinem nulli prorsus exhortationi cessuram. Quem tunc temporis maxime adoriendum putabant, cum Starcatherum, cuius plerisque formidolosa uirtus extabat, negotiosum abesse cognoscerent. Cunctante uero Frothone seque cum amicis super dando responso collocuturum dicente superuenit Starcatherus piratica iam regresssus, qui ex hoc maxime prouocationis habitum reprehendit, quod diceret regibus non nisi in compares arma congruere eademque aduersum populares capienda non esse: per se uero tamquam obscuriore loco natum pugnam rectius amministrandam existere.

5.17. Igitur Saxones Hamam, qui apud eos gymnicis palmis clarissimus habebatur, multis aggressi pollicitationibus, si duello operam commodaret, molem corporis eius auro se repensuros esse promittunt illectumque pecunia pugilem ad campum confluctui deputatum militaris pompe tripudio prosequuntur. Hinc Dani Starcatherum regis sui partes exequuturum ad certaminis locum militie insignibus ornati perducunt. Quem Hama etate marcidum iuuente fidutia despicatus defunctum uiribus senem lucta quam armis excipere preoptauit. Eundem adortus terre nutabundum adegerat, ni fortuna, que uinci uetulum non sinebat, iniurie restitisset. Ita enim impellentis Hame pugno obrutus memoratur, ut genibus nixus humum mento contingeret. Quam corporis nutationem egregia ultione pensauit. Nam ubi resuscitato poplite manum expedire ferrumque distringere licuit, medium Hame corpus dissecuit. Complures agri sexagenaque mancipia uictorie premium extitere.

§3d. Here is my translation (guided by the earlier translation of Fisher 2015, which I have modified here and there):

5.16. Meanwhile the Saxons were mounting rebellion [against the Danes] and giving particular thought to how they could eliminate [king] Frotho, so far undefeated, in a way that would bypass a mass conflict. Thinking that the best way to do it would be individual combat, they sent emissaries to issue a challenge to the king, aware that he always embraced every danger eagerly and that his high spirit would certainly never give way to any admonition. Once they knew that Starcatherus, whose bravery intimidated most men, was occupied elsewhere, they reckoned that this was the time to accost Frotho. But while the king was hesitating and saying that he would have to consult his friends about a reply, Starcatherus appeared on the scene, back from his sea-roving [= Viking activities]; he most strongly objected to the idea of the challenge, because, as he pointed out, such fights were not appropriate for kings except against their equals and certainly they should not be undertaken against men of the people; more properly it was up to him [= Starcatherus], as one born in a less luminous situation, to handle this fight.

5.17. So, the Saxons approached Hama, famous among them for his athletic victories, with many assurances that if he would throw his energies into a single combat, they would repay him with the weight, in gold, of his mountainous bulk; attracted by the prize money, the champion [pugil ‘fist-fighter’] was accompanied by a jubilant procession of warriors to the field marked for the combat. On their side the Danes, all decked out in their war gear, led Starcatherus to the place of combat, so that he could fulfill the role [partes] of his king. Hama, exulting in his youth, was scornful of an opponent feeble with age and chose to engage with this worn-out old man by way of wrestling [lucta] instead of encountering him by way of weapons. He went at Starcatherus and would have sent him reeling to the earth, had not Fortune, who would not allow the veteran to be overcome, stopped him from being harmed. It is recorded in memory that he [= Starcatherus] was struck down with such force by the driving fist [pugnus] of Hama that he was brought to his knees and touched the ground with his chin. Starcatherus took fine compensation for being thrown off balance: as soon as he regained his feet and had a hand free to draw his sword, he cut Hama’s body in half. A large portion of land and sixty slaves were the price of his victory.

§4. This Old Norse myth about an uneven boxing match between an elderly Scandinavian hero Starkaðr and a youthful Saxon hero named Hama, who is actually described as a pugil ‘fist-fighter’ in the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus as also in the Historia of Olaus Magnus, helps us see how the old hero may have earned the title pugil ‘fist-fighter’ in his own right. In the myth we have just considered, the hero Starkaðr is engaging in single combat on behalf of the Danes, but in other myths, he could have been fighting in single combat on behalf of the Swedes—hence his full title pugil Sueticus ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’ in the illustration found on the Carta of Olaus as also in the woodcut for the story about Starkaðr as reported by the same Olaus in that author’s Historia. Moreover, as Stephen Mitchell points out to me, there were other Norse heroes who received the title pugil Sueticus ‘fist-fighter of Sweden’ in other stories, as we see from the application of this same title to the hero Arngrim at 5.13.1 in the Gesta Danorum by Saxo Grammaticus. In that narrative of Saxo about victories won by Arngrim in battles on behalf of the Swedes, however, we find no retelling of any story about any one-on-one boxing match. Similarly, we find no retelling of any story about a one-on-one boxing match involving Starkaðr in battles where this hero fights on behalf of the Swedes instead of the Danes. In any case, the old hero Starkaðr is a pugil for the Danes, not for the Swedes, in the story about the killing of the Saxon boxer named Hama, and I am arguing that this particular story is cognate with the little-known Greek story about another uneven boxing match—this one between Hēraklēs and the two rival athletes who actually defeated him on the occasion of the second Olympics ever held.

§5. If the Greek story had been well known in medieval times, I should add, we might have suspected that such a story about Hēraklēs had served as a model for the Old Norse story about Starkaðr. After all, the similarities between ‘Hercules’ and Starcatherus were recognized by the learned Scandinavian transmitters of stories about Starkaðr—so much so that the narrative of Olaus Magnus about Starkaðr actually refers to him at one point as an alter Hercules, ‘another Hēraklēs’: this happens at p. 161 of the Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus by Olaus Magnus—though not in the context of the ensuing story about the uneven boxing match between Hama and Starcatherus. That said, I must nevertheless insist that the similarities between the Old Norse and the ancient Greek boxing matches are not at all close enough to justify our supposing that the Scandinavian transmitters of the Starkaðr myths—no matter how learned they may have been in the Greco-Roman classical tradition—would have somehow modeled the myth about the duel of Starkaðr with Hama on a barely-known myth about a loss by Hēraklēs in a boxing match—a myth that remains most opaque to this day. That said, I grant that other features of the Starkaðr story, like the positioning of a ferocious lion that we see in the foreground of the picture that labels this hero as a boxer, may possibly be a matter of borrowing from a cognate figure of Hēraklēs, since the linking of the Greek hero with the lionskin that he wears in Greek traditions is so ubiquitous. The same can be said, perhaps, about the club that we see positioned next to the hero’s sword in the same picture.

§6. So far, I have been arguing that the role of the Greek hero Hēraklēs as a boxer was cognate with the role of the Germanic hero Starkaðr as, likewise, a boxer. In using the term “cognate,” I am saying, in effect, that the myths about Hēraklēs as transmitted in the Greek language and the myths about Starkaðr / “Starcatherus” as originally transmitted in Old Norse and as later mediated in Latin paraphrases derive from an “Indo-European” system of mythmaking—just as the Greek and the Old Norse languages derive from a common language known to linguists as “Indo-European.” Holding on to this idea of cognate traditions, I will now start to widen the perspective while continuing to compare details I find in Greek myths about the hero Hēraklēs and in latinized Old Norse myths about the Scandinavian hero Starcatherus. At the start, the widening of the comparative perspective will seem slight, but the ultimate results, I hope, will lead to a significantly wider view. My ultimate conclusion, as we will see, is that the Greek figure of Hēraklēs, like the Germanic figure of Starkaðr, can be reconstructed an ‘Indo-European’ mythological construct. And the more we compare Hēraklēs with his Scandinavian counterpart Starkaðr / “Starcatherus,” the more evident this conclusion will become.

§7. Here, then, is how I will start to widen the lens for now: I will view Hēraklēs not only as a free-style wrestler—that is how I have been describing him since Essay 2—but also as a free-style boxer. Such a view finds its expression in a traditional ancient Greek athletic event known as the pankration, informally translatable as ‘maximum force’—and worth comparing with a combat sport known today as mixed martial arts.

§8. To develop the point I just made, I start with a general myth reported by Diodorus of Sicily (4.14.1–2), who says that one of the greatest of all the achievements of Hēraklēs was his founding of the Olympics, that is, of the Olympic festival at Olympia. Further, as Diodorus also says in this same context (4.14.2), Hēraklēs not only founded this major festival: he also competed and won in every athletic event on the prototypical occasion of the first Olympics. This kind of generalizing formulation about Hēraklēs and the Olympics is of course comparable with what we read at a later point in the narrative of Diodorus (4.17.4), already reported in Essay 2, about a prototypical athletic victory of Hēraklēs in his free-style wrestling match with the ogre Antaios. Here the narrative of Diodorus glorifies Hēraklēs as a culture hero whose athleticism is linked with his role as promoter of the very foundations of Greek civilization. So also in the case of the Olympics: the glorification of Hēraklēs as the founder of athletic events featured at this festival is linked with his overall role as promoter of Greek civilization.

§9. But ancient Greek myths also show alternative ways of looking at the involvement of Hēraklēs in the Olympics. I now turn to a much more complicated myth or set of myths, mediated by Pausanias, who lived in the second century CE. In a lengthy narrative, Pausanias (5.7.6–5.9.6) sets out to collect a wide variety of alternative myths as he embarks on tracing the evolution of the athletic events at the festival of the Olympics from the very beginnings all the way to his own present time, and, in terms of this narrative, Hēraklēs was not even the original founder of the Olympics. Rather, as we will see, he had a more specialized role. Moreover, as we will also see, there existed not one but at least two different heroes named Hēraklēs, separated from each other by many generations, and each one of the two had specialized roles in the evolution of the Olympics.

§9a. According to one particular myth recorded by Pausanias (5.7.6), there was a First Hēraklēs, who originated from Mount Ida in Crete, and this hero competed in the footrace at Olympia, winning that race in rivalry with his four brothers. In terms of this myth, a primordial contest of the Five Brothers in running become formalized as a competition in one single Olympic event, which was a footrace—or, to describe it in Classical Greek terms, the stadion. For now, at least, the athletic competitions of a prototypical Olympic festival were limited to one single event, footracing.

§9b. Then, as we read further in Pausanias (5.8.3), there emerged, generations later, a Second Hēraklēs—this one came from Thebes (5.8.8)—and he too competed in the Olympics. Once again, the competition became foundational, and, this time, the number of athletic events was augmented: instead of simply one athletic event, a footrace, there was now an additional set of further athletic events. And the Second Hēraklēs was the winner in two of these additional athletic events, wrestling and the pankration (5.8.4). Also, there was now another athletic event, boxing, and the winner of the foundational competition in boxing was the hero Pollux (Polydeukēs), while his twin brother Castor (Kastōr) was the winner in the footrace.

§10. As we see from these myths reported by Pausanias, the hero Hēraklēs of Thebes is pictured as a champion of the pankration, an early form of combat sport that was not yet as specialized as wrestling, which excludes punching, or as boxing, which includes the wearing of leather straps for the protection of wrists and knuckles.

§11. Here I return to an earlier point in this essay. I see a remarkable parallel in the picturing of the Saxon hero Hama in the Gesta Danorum of Saxo Grammaticus (5.17), who is described in this narrative as preferring lucta ‘wrestling’ to the use of weapons when he engages in mortal one-on-one combat with the hero Starkaðr. We saw that our wrestler makes the first move by using his fist: he violently punches Starkaðr, who as we also saw is conventionally designated as ‘fist-fighter’ in his own right. So, the form of wrestling championed by Hama also included elements of boxing. These Germanic heroes, then, are champions in an early form of combat sport that closely resembles the athletic skills of the Greek hero Hēraklēs in the myth that told about his winning in two Olympic events, wrestling and the pankration. And we see in the Germanic myth a fusion of wrestling and boxing that is comparable.

§12. Here is a further point of comparison. In a Greek myth about the prototypical athletic competitions in the festival of the Pythia at Delphi, as we read in scholion “a” at lines 38–43 of the hypothesis for Pindar’s Pythian Odes, the hero Telamon was the first ever to win in the athletic event of wrestling, while Hēraklēs was the first to win in the pankration. Such a mythological focusing on Hēraklēs as a champion of the pankration is relevant, I think, to the stratagem that this hero devised, myth has it, in his killing of the Nemean Lion: since this beast was impervious to weapons, the hero choked it to death, as we read in Diodorus (4.11.3–4). And the hero’s choke-hold, as described in this myth, is an athletic maneuver that typifies the pankration. By contrast with the regulations of wrestling, the pankration was relatively unregulated, allowing for not only punching and kicking but even choking.

§13. And here we must keep in mind that the killing of the Nemean Lion by Hēraklēs, viewed in the Greek myth as a feat of athleticism, is simultaneously viewed in the same myth as a demonstration of the hero’s role as a primary defender of Greek-speaking populations: after all, the Nemean Lion was a major threat to civilization, terrorizing the local population until Hēraklēs intervened. Similarly in the case of the myth about the killing of the ogre Antaios by Hēraklēs, celebrated as another feat of athleticism, this time in the form of wrestling, the victory of Hēraklēs is simultaneously viewed as another example of the hero’s role as a primary defender of civilization. And such a role can be seen as an overall subtext in all the various different myths about the athleticism of Hēraklēs, including myths about his participation in the founding of athletic events at the festival of the Olympics. We have already seen this hero in some contexts as a winning contestant in all Olympic athletic events, while in other contexts his pattern of winning is limited to such special athletic events as running, wrestling, and the pankration. Either way, such patterns of athleticism, as we will go on to see, correspond to the overall role of Hēraklēs as a primary culture hero of the Greeks. And an ideal point of comparison, as we will also see, is the Germanic Starkaðr, culture hero of Scandinavian populations.