2022.07.04 | By Gregory Nagy

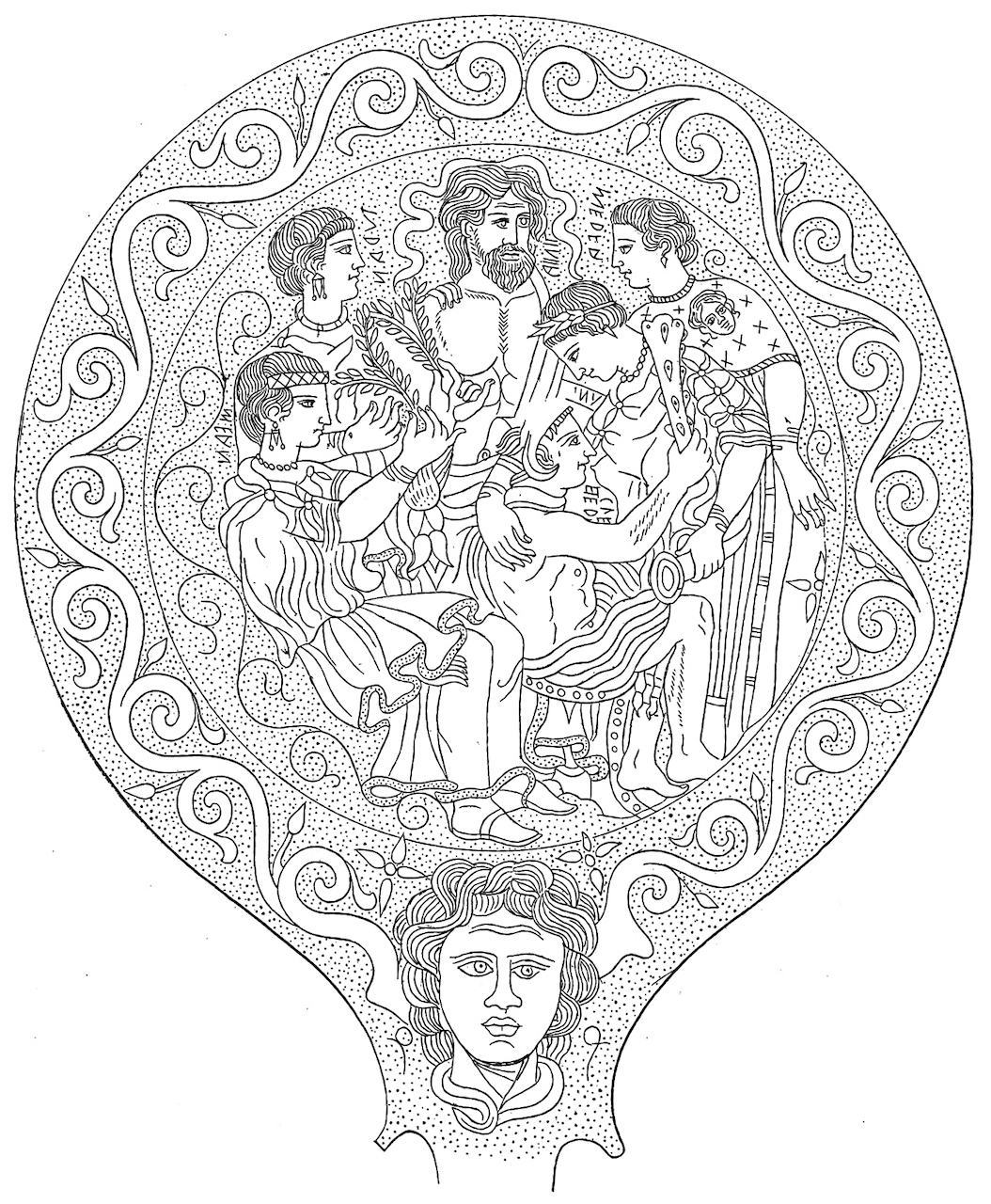

§0. The image that I have chosen as the leading illustration for this essay highlights a benevolent side of a relationship, in myth, between the hero Hēraklēs on the one hand, and, on the other hand, the goddess Hērā together with the god Zeus, her divine consort. The image graces the other side of a hand-held mirror unearthed in ancient Etruria, and it pictures a scene derived from ancient Greek myth, mediated by Etruscan reception of this myth. Pictured is the goddess Hērā showing her benevolence toward the hero Hēraklēs, breast-feeding him as if he were a newborn child. The goddess, who is Hērā in the Greek language, is named Uni in the Etruscan language, and her Etruscan name is the equivalent of her Roman counterpart, the goddess named Juno, Iūnō in Latin. As for Hēraklēs, his Etruscan name is Hercle, equivalent of his own Roman counterpart, the hero named Herculēs, pronounced exactly that way in Latin. Presiding over this scene of benevolence in the picture is the divine husband of Uni, who is named Tini/Tinia in the Etruscan language. This name Tini/Tinia is the Etruscan equivalent of the god’s Roman counterpart, who is the god named Jupiter, Iūppiter in Latin. Jupiter is of course Zeus himself in the Greek language. The benevolent stance of the god Tini/Tinia in this picture, as he presides over the breast-feeding of Hercle by the goddess Uni, conveys an ancient Greek idea of absolute benevolence on the part of both Hērā and Zeus together toward the hero Hēraklēs. Here in Essay 3, I will show that such a positive mythological construct of divine benevolence shown by Hērā and Zeus to Hēraklēs in this scene needs to be analyzed in the light of a corresponding negative mythological construct, which centers on the malevolence of Hērā toward Hēraklēs. This hero, during his lifetime on Earth, was the son that Hērā never had. He became her son only after death, by way of his apotheosis on Mount Olympus. During the hero’s lifetime on Earth, by contrast, the goddess Hērā persecuted the hero Hēraklēs, this illegitimate son of Zeus. The god had impregnated a mortal woman, Alkmene, biological mother of Hēraklēs. And this negative mythological construct involving the relationship of Hērā and Zeus with Hēraklēs is essential, as we will see, for understanding how such a relationship shaped the destiny of Hēraklēs as a model for athletes.

§1. I start with the benevolent side of the relationship. The question is, why would Hērā/Uni breast-feed the adult Hēraklēs/Hercle as if he were a newborn child? That is, why would Hērā give Hēraklēs such a gift, performing such a benevolent gesture? The answer has to do with a central myth about Hēraklēs—about his death and subsequent immortalization, noted already in Essay 1. According to that myth, as we will now see in more detail, the death of Hēraklēs frees him from the dysfunctional world of myth, so that he may now be reborn, entering the functional world of ritual. And the agent of rebirth, as we will also see, is the goddess Hērā herself.

§2. But what do I mean when I speak of a world of ritual that supersedes a world of myth? For Hēraklēs, such a world of ritual becomes a reality in an exalted form of hero cult, and he becomes immortalized as an exalted cult hero. In terms of my argument, which I first developed in The Best of the Achaeans (Nagy 1979/1999:302–303 = 18§2), the antagonism that existed between Hērā and Hēraklēs in the world of myth gave way to a nurturing symbiosis for the two of them in the world of ritual. There is an admirable summary of this argument of mine in a most incisive article by Nicole Loraux (1990:44).

§3. A moment ago, in §1, I spoke about Hērā as the agent for a rebirth of the hero. Here I turn to the relevant narrative of Diodorus of Sicily, who as we have seen lived in the first century BCE. In the narrative of Diodorus about the life and times of Hēraklēs, we find a stylized but nevertheless quite explicit reference to such a rebirth, and the would-be mother who now gives birth to Hēraklēs is the goddess Hērā herself. In The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours (H24H 1§46), I offer a paraphrase of the relevant narrative by Diodorus (4.39.2–3), which I epitomize here.

Hēraklēs dies on the heights of Mount Oeta, blasted away by a thunderbolt of Zeus, but then he regains consciousness and finds himself on the heights of Mount Olympus, in the company of the gods. He has become immortalized, adopted by the Olympian theoi ‘gods’ as one of their own. He has experienced apotheosis. Hērā now changes identities: no longer a stepmother to Hēraklēs, she becomes his virtual mother. The procedure is described in some detail by Diodorus, and I translate literally (4.39.2): ‘Hērā got into her bed and drew Hēraklēs close to her body; then she ejected him through her clothes to the ground, re-enacting [= making mīmēsis of] genuine birth’ (tēn de teknōsin genesthai phasi toiautēn: tēn Hēran anabasan epi klinēn kai ton Hēraklea proslabomenēn pros to sōma dia tōn endumatōn apheinai pros tēn gēn, mimoumenēn tēn alēthinēn genesin).

§4. I follow up with the argument I presented in The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours (H24H 1§§47–48). Birth by Hērā is the hero’s rebirth, a birth into immortality. But the rebirth can only happen after death. The hero can be immortalized, but the fundamental painful fact remains: the hero is not by nature immortal. By now we can see that the name Hēraklês / Hērakléēs, which means ‘he who has the glory [kleos] of Hērā’, marks both the medium and the message of the hero. But when we first consider the meaning of the name of Hēraklēs, our first impression is that this name is illogical: it seems to us strange that Hēraklēs should be named after Hērā—that his poetic glory or kleos should depend on Hērā. After all, Hēraklēs is persecuted by Hērā throughout his heroic life on Earth. And yet, without this unseasonality, without the disequilibrium brought about by the persecution of Hērā, Hēraklēs would never have achieved the equilibrium of immortality and the kleos or ‘glory’ that makes his achievements live forever in song.

§5. In terms of my argument, song is anchored in the functional world of ritual, in the world of hero cult. We see equilibrium here. We see seasonality. The unseasonality, by contrast, becomes visible only in the world of myth, retold in the ritualized context of song.

§6. The goddess Hērā presides over the seasonality, and that is what her name means, seasonality. As I have argued for over fifty years by now (starting with Nagy 1972:51–52 / 770–771) the etymology of both names, Hḗrā and Hēraklês / Hērakléēs, as also of the noun hḗrōs ‘hero’, can be explained in terms of Indo-European linguistics. Etymologically, the name of the goddess, Hḗrā, accentuates her benevolent side, which is seasonality, as we see from the related noun hṓrā, which actually means ‘season, seasonality’. (For more on these etymologies, I cite the following: Nagy 1979/1999:303 = 18§2 318–319; Davidson 1980:199; Sinos 1980:14; Nagy 1990a:140n27 = 5§7; Nagy 1990b:136; Nagy 2013 1§49.)

§7. In her wide-ranging book on the goddess Hērā, the etymological explanation that I offer here is accepted by Joan O’Brien (1993:116n9), but her view of the positive and the negative aspects of the goddess differs from mine. For O’Brien, the benevolence and the malevolence of Hērā toward Hēraklēs can be explained in terms of older and newer attitudes toward the goddess as she evolved through time. For me, on the other hand, the malevolence is just as old as the benevolence, but such negative and positive aspects of the relationship between divinity and hero can be explained in terms of antagonism in myths about heroes and symbiosis in rituals that frame such myths in the context of hero cult. Again I cite my argument in The Best of the Achaeans (Nagy 1979/1999:302–303 = 18§2) and the summary by Nicole Loraux (1990:44).

§8. With regard to the positive as well as the negative aspects of the relationship between divinity and hero, I have compared in another work (Nagy 2019.08.08), again in terms of Indo-European linguistics, the death scene of the Greek hero Hēraklēs with the death scene of the Indic hero Śiśupāla as narrated in the epic Mahābhārata (II 42.14–25):

In the case of Śiśupāla, his life-force is absorbed in a flash of light generated by the god Viṣṇu/Kṛṣṇa, and this flash, explicitly compared to lightning in the narrative, comes out of the hero’s body and goes inside the god’s body. Comparably in the case of Hēraklēs, his life-force is absorbed in a flash of lightning generated by the god Zeus, and this flash goes inside the body of the goddess Hērā. Such an entry is implicit in the ensuing stylized detail: as we have seen, Hērā notionally gives birth to the hero, so that Hēraklēs must have been inside Hērā—at least, notionally so. Now the hero can be born, really reborn, from his new mother, Hērā, who has thus given him a life that becomes eternal. Thus an antagonism between Hērā and Hēraklēs has led to an eventual symbiosis between divinity and hero.

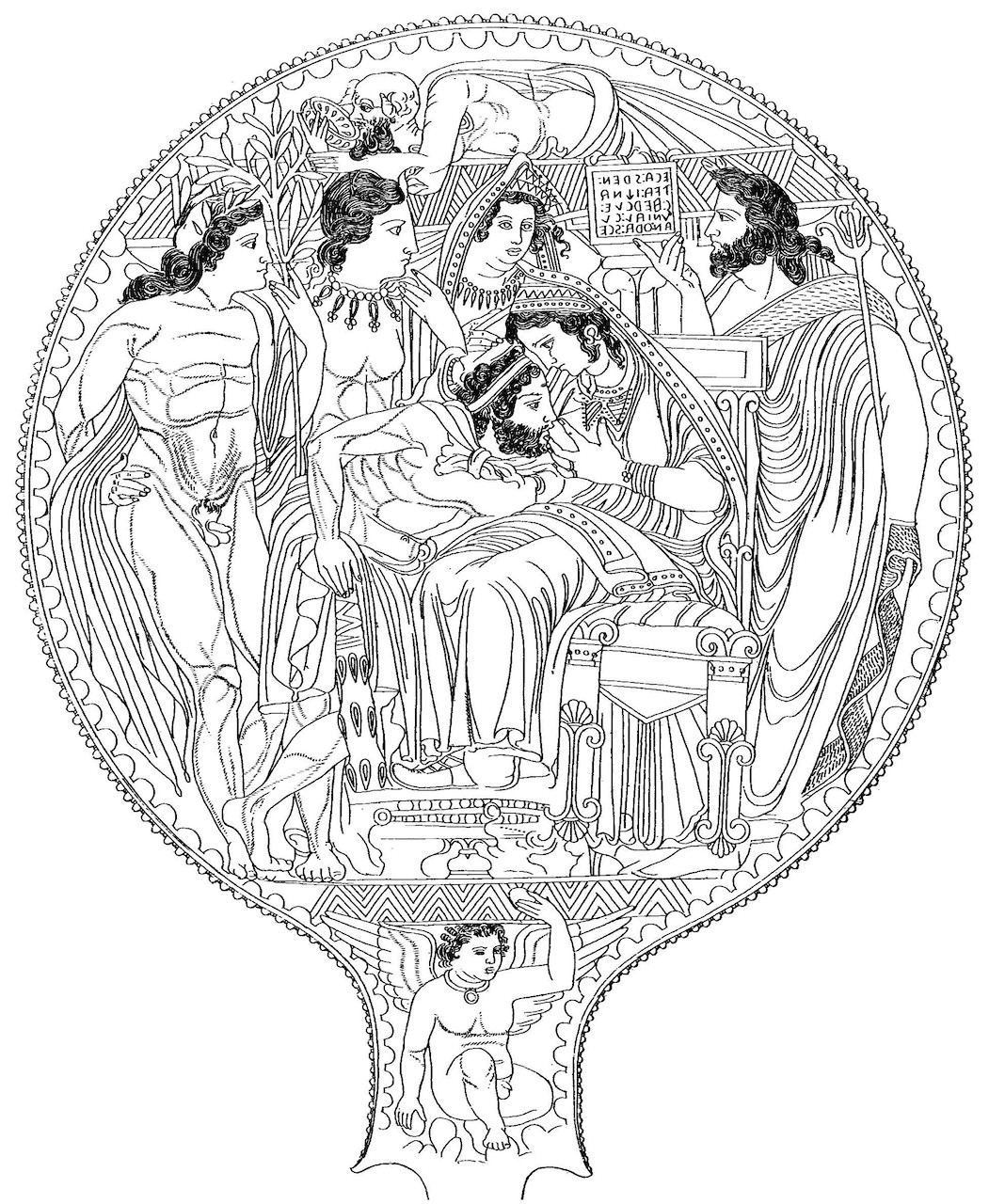

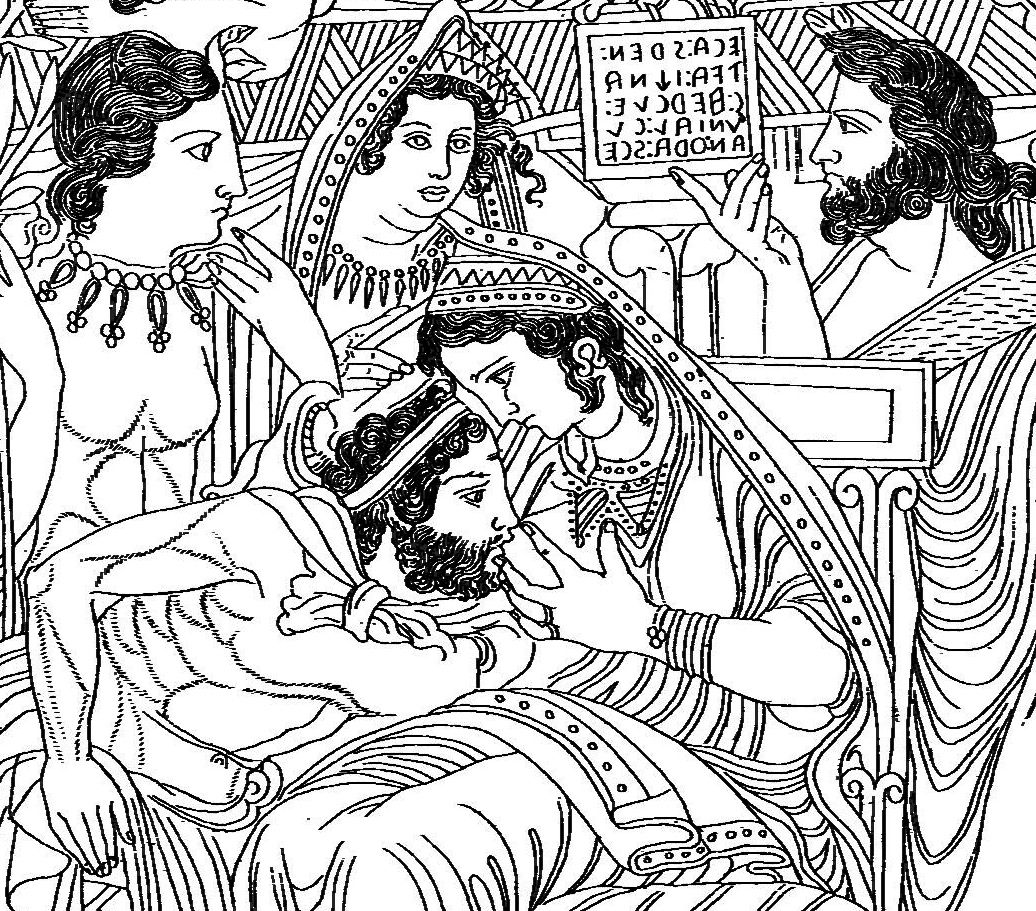

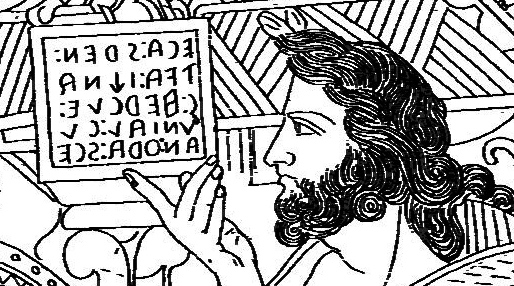

§9. Once immortalized, Hēraklēs becomes the devoted son of Hērā, who gives birth to him, at least notionally, as we have read in Diodorus (4.39.2). We find another example of such symbiosis in the image, engraved on the back of an Etruscan bronze mirror, that I showed in the main illustration for this essay. And here is another such Etruscan image:

Once again we see an immortalized Hēraklēs, the Etruscan Hercle, being breast-fed by his new mother Hērā, the Etruscan Uni, and attended by her consort Zeus, the Etruscan Tini. The figure of Zeus, named Tini here, is holding up for all to see a tablet inscribed in Etruscan lettering, where the text is evidently validating what I describe here as a symbiosis of hero and goddess. I note especially the lettering HERCLE at line 3 and VNIA, in the genitive, at line 4. (Further comments by Jaan Puhvel 1987:251.)

§10. Having first considered the eventual positive side of the relationship between Hērā and Hēraklēs, I now turn to the negative side, as retold in earlier parts of the story. Tracking the various myths that tell about the antagonism between goddess and hero, I start with a most striking example. We read, in a retelling by Diodorus (4.9.6), that the goddess Athena had once upon a time persuaded a hesitant goddess Hērā to breast-feed Hēraklēs when he was still a baby; the hero’s mortal mother had abandoned him and exposed him to the elements, since she feared Hērā. This symbiotic gesture, where Hērā breast-feeds the infant Hēraklēs, led to early antagonism, as we read further in Diodorus (4.9.6–7): while the breast-feeding was underway, the baby sucked too hard and bit the goddess on the breast, so that Hērā tossed the baby aside, and Athena had to bring him back to his mortal mother. In further versions of the myth, it is added that Hērā, when she abruptly pulled her breast away from the biting baby, spilled her milk into the sky, thus unwittingly creating the Milky Way (for example, “pseudo-Eratosthenes” Catasterismi 3.44 ed. Olivieri).

§11. There is a comparable instance of antagonism in the Homeric Iliad, 5.392–394, where we read that the adult Hēraklēs had once upon a time wounded Hērā by shooting a poisoned arrow into her right breast, causing an incurable algos ‘pain’ (394).

§12. That wounding happened in the past. But now, in the present time of the Homeric narrative in Iliad 5, the goddess Hērā is getting ready to enter the scene of man-to-man combat in the Trojan War: first she outfits her divine chariot (719–732) and then she rides off from Olympus, driving her divine horses across the vast space separating sky from earth (768–769), finally arriving at the Plain of Troy (772–775). Joining Hērā for the cosmic ride and standing side-by-side with her on the platform of this heavenly ‘chariot of fire’ (okhea phlogea, 745) is Athena, who has fully armed herself for combat in war (733–744). The mission for this divine chariot fighter Athena and for her divine chariot driver Hērā is to stop the onslaught of the raging god of chaotic war, Ares, who has intervened in the man-to-man combat by overtly fighting on the side of the Trojans. In the action that follows (verse 776 and thereafter), Athena as a goddess of organized warfare will stop Ares by aiding her protégé, Diomedes the Achaean, who will now achieve his greatest success as a warrior: he gets to inflict a serious wound on Ares, thus putting a temporary end to the war-god’s chaotic onslaught. The success extends further, since Diomedes will now go on to wound Aphrodite, who has been aiding her son, her own protégé, Aeneas the Trojan. I see here a parallel in the embedded narrative about the wounding of Hērā by Hēraklēs, as retold in Iliad 5, where it is Hērā and not Aphrodite who gets wounded by a mortal hero.

§13. Such a wounding of Hērā by Hēraklēs in myth defines a special kind of anger that this goddess feels toward that hero—and, on occasion, toward other heroes as well. This anger is mixed into her milk, infected by the poisoned arrow that wounded her breast. The question is, can there be a cure in ritual for the incurable pain that this wound has caused in myth? And the answer to this question is already at hand when we consider the future reconciliation between Hērā and Hēraklēs in the context of the hero’s apotheosis on the heights of Olympus. The toxicity of the milk of Hērā is cured in the benevolent scene of the hero’s apotheosis, where Hērā breast-feeds the reborn Hēraklēs as her new son.

§14. In earlier parts of the story, however, we see what seems then to be a vicious circle of seemingly never-ending toxicity. I epitomize here my analysis, taken from a larger project centering on conundrums of divine motherhood (Nagy 2020.04.10):

§14.1. In the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, verses 300–355, we read that Hērā was angry at her brother and husband Zeus for fathering—without her female participation—the goddess Athena. Hērā in her anger now went ahead and found a way to conceive and to give birth to the serpentine monster Typhon/Typhoeus—without any need for male participation in the form of insemination. The ‘anger’ of the goddess here is relevant: the word is kholos, χολωσαμένη and χολώσατο at verses 307 and 309. To be contrasted with this myth about Hērā, as Joan O’Brien points out (1993:101n41), is an alternative myth that we find in the Hesiodic Theogony, where Hērā is only the would-be mother of Typhon/Typhoeus. We read at verses 821–822 how Mother Earth, the immortal Gaia/Ge, was inseminated by the immortal Tartaros, and she thus conceived and gave birth to Typhon/Typhoeus. As noted in the commentary of Martin West (1966:252), the names Typhon at verse 306 and Typhoeus at verse 821 refer to the same monstrous son, who is then described at verse 825 with the words ophis and drakõn, both of which mean ‘serpent’. Hereafter, I will refer to this serpentine monster simply as Typhon.

§14.2. Although Hērā does not conceive or give birth to the serpentine Typhon in the Hesiodic Theogony, she nevertheless breast-feeds the monster’s progeny, who are themselves all serpentine: as we read at verses 313–315, the goddess nurses the serpentine Hydra of Lerna—the verb for ‘nurse’ here is trephein at verse 314 (θρέψε). At verses 306 and 304 respectively, we find that the father of the Hydra is the serpentine Typhon, and that the mother is a likewise serpentine Ekhidna, whose name corresponds to the common noun ekhidna, meaning ‘viper’ in Greek.

§14.3. In view of such serpentine features marking the monster Typhon, I will have to circle back to the Homeric Hymn to Apollo, verses 300–355, where we find yet another such feature of this monster. But first I need to review a glaring detail that I have already noted about the overall story told in those verses of the Homeric Hymn. Here is that detail: by contrast with the Hesiodic Theogony, which says that Mother Earth, not Hērā, gave birth parthenogenetically to Typhon, the Hymn says at verses 305–307 that this monster was born parthenogenetically from Hērā, not from Mother Earth. But the story goes further, and here is where we can see yet another serpentine feature of Typhon. We now learn that Hērā, after having given birth to Typhon, handed him over to the ‘She-Dragon’ of Delphi, to be ‘nursed’ by this serpentine would-be mother—and the verb for ‘nurse’ here is once again trephein, at verse 305 (ἔτρεφεν). My translation ‘She-Dragon’ approximates the original Greek name Drakaina at verse 300 of the Hymn.

§14.4. I find it essential here to compare the chicken-and-egg reasoning in the myth about the nursing of the Hydra by Hērā at verse 315 of the Hesiodic Theogony: as we see there, the goddess nursed the serpent because she was angry at Hēraklēs—and the word for her anger there is kotos, κοτέουσα at verse 315.

§15. Also relevant is my analysis, in another project (Nagy 2020.04.03), where I connected this myth about the breast-feeding of the serpentine Hydra by Hērā with two other myths. In one myth, centering on the Trojan War, we read in the Homeric Iliad, 4.31–36, that it was not enough for Hērā to accept the death of all Trojans: she would require it. And, similarly in the other myth, involving the antagonism between Hērā and Hēraklēs, she would require the doom of the hero, as we have already seen. But, in this other case, not only is the anger of the goddess eventually cured. Likewise cured is the seemingly incurable wound caused by the poisoned arrow shot into her right breast by Hēraklēs in that incident retold at verses 392–394 of Rhapsody 5 of the Iliad, where we read that Hēraklēs thus caused an incurable algos ‘pain’, highlighted at verse 394. When we look beyond this part of the myth, we can see what is left unsaid in the Iliad: once Hēraklēs is reborn, he is breast-fed by Hērā, and I have highlighted in this essay some relevant images from the ancient world. This benevolent gesture on the part of the goddess shows that the wound inflicted once upon a time by the arrow of Hēraklēs, incurable in the heroic world of myth, has been cured in the post-heroic world of ritual, where the pollutions retold in myth may be purged by way of re-enacting myth in ritual.

§16. But how are we to imagine the sequence of mythological events leading from the wounding of the right breast of Hērā all the way to the breast-feeding of Hēraklēs by the goddess? To address this question, I make a start here by tracking other myths that tell of Hērā in the act of breast-feeding:

§16.1. As we have already seen, Hērā breast-feeds a monstrous serpent, the Hydra of Lerna, in the Hesiodic Theogony 313–314; this Hydra is the progeny of another monstrous serpent, the Ekhidna. Further, Hērā also breast-feeds the Lion of Nemea, another progeny of the Ekhidna, in Theogony 327–329.

§16.2. Hērā breast-feeds Thetis, mother of Achilles, as we read in Iliad 4.59–60; Thetis in turn breast-feeds Achilles, as we read in Iliad 16.203.

§17. The myth about the breast-feeding of the serpentine Hydra by Hērā is I think relevant to other myths that tell how Hēraklēs, when he split open the body of the monster after killing it, made poisoned arrows by dipping the metallic tips into the gall that flowed from the gall bladder of the Hydra. The sources are Sophocles, Trachinian Women569–577; Diodorus of Sicily 4.11.6; the Library of “Apollodorus” 2.5.2 p. 189 ed. Frazer; Pausanias 2.37.4.

§18. In three of these sources (Sophocles, Diodorus, Pausanias), it is made explicit that any wound caused by the poisoned arrows of Hēraklēs will be incurable. And here I return to the pain, described as incurable, of the wound caused by the arrow shot by Hēraklēs into the right breast of Hērā, narrated in Iliad 5.392–394. I ask myself: is the pain of this wound incurable because it was infected by the gall that flowed from the bladder of the Hydra—the gall that poisoned the tips of the arrows shot by Hēraklēs? There can be no certain answer, but one thing is for sure: the same gall that poisoned the arrows of Hēraklēs killed not only Nessos, the Centaur who tried to rape Deianeira, wife of Hēraklēs: it also eventually killed Hēraklēs himself, as we read in the myth as retold by Diodorus (4.36.4–5), where it is made clear that the toxic liquid that killed Hēraklēs by mere contact with his skin was a mixture of olive oil, blood, semen from the Centaur, and, fourth, gall smeared on the tip of the poisoned arrow that had killed the Centaur.

§19. In Greek, the word that I translate as ‘gall’ here is kholḗ. But another Greek word that can also mean ‘gall’ or ‘bile’ is khólos itself, as we see from the careful etymological and contextual analysis of these two words kholḗ and khólos in a book on Homeric anger by Thomas R. Walsh (2005:217–225). In short, kholos as the anger of Hērā—and as the anger of Achilles—could be visualized as yellow bile.

§20 And here we find the ultimate connection between the kholos or ‘anger’ of Hērā and the kholos or ‘anger’ of Achilles, conjured together in the words of Achilles about the poetics of anger in Rhapsody 18 of the Homeric Iliad: as Joan O’Brien (1993:93) has noted, the anger of Hērā is transmitted to Achilles by his mother’s milk, since Hērā breast-fed Thetis just as Thetis breast-fed Achilles, as I pointed out already with reference to Iliad 16.203. I think that the toxic gall in the mother’s milk of Hērā, infected by the poisoned arrow of Hēraklēs, is transmitted by way of Thetis to Achilles.

§21. In his own words, spoken at verses 200–209 of Rhapsody 16 in the Iliad, Achilles shows an awareness of the gall that infected the mother’s milk of Thetis. He is speaking here to his fellow warriors, the Myrmidons, admitting to them that they must surely be shocked by the savagery of his anger, which he calls kholos at verse 206. Achilles is already saying at verse 203 that he would not blame his comrades for thinking that he must have been breast-fed by Thetis not on mother’s milk but on anger, and here too at verse 203 he uses the word kholos, just as he uses it later at verse 206—except that this time, at verse 203, kholos can refer directly to gall, real gall mixed in milk, not only to gall as a metaphor for anger. As Laura Slatkin has pointedly shown in her book about Thetis (2011), this goddess has her own anger, inherited from her by Achilles. And, as we now see further, the hero’s anger is also transmitted through his mother’s toxic milk, which is transmitted in turn from the gall mixed into the mother’s milk of Hērā. And the hero is aware, I now argue, of the anger that comes from Hērā, since he is also aware of the malevolence shown by the goddess toward Hēraklēs when that hero was alive—to be contrasted with the benevolence of this same goddess toward that same hero when he is reborn after death. What galls Achilles, though, is that he too, like Hēraklēs, must accept death as a cure for his own anger. By contrast, unlike Achilles, Hēraklēs must accept death as a cure for the anger of Hērā herself. Once this anger is cured, the mother’s milk of the goddess will no longer be toxic for the hero.

§22. As I bring this essay to a close, I highlight a detail about the Lion of Nemea. This monster, like the Hydra of Lerna, is pictured as a nursling of Hērā in the Hesiodic Theogony: at verse 328 we read how the goddess nursed this monster—and the verb for ‘nurse’ here is once again trephein (θρέψασα). Like the Hydra, the Lion too has been nurtured by Hērā to become a most dangerous threat to Hēraklēs, but the hero kills the monster, as we read at verse 332, just as he kills that other most dangerous menace, the Hydra.

§23. Both the Lion of Nemea and the Hydra of Lerna are featured as major adversaries in the sequence of the Labors, as they are called in English, that were performed by the hero Hēraklēs. But it is the Greek word translated as ‘Labor’ in English that reveals the essential element in the entire complex of myths about the Labors of Hēraklēs—and that shows the vital relevance of the Labors as a model for athletes. The word is attested already in the Homeric Iliad, in Rhapsody 19, lines 76-138, where we read a retelling of the myth that told about the malevolence of Hērā toward Hēraklēs. I have paraphrased the retelling in The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours, and I epitomize here my paraphrase (starting at H24H 1§37 and extending through 1§43):

My epitome here focuses on a big mistake made by Zeus. This mistake drives the story, as retold by Agamemnon at Iliad 19.95–133, about the relationship of Hēraklēs with that hero’s inferior cousin Eurystheus. According to that story, the goddess Hērā tricked Zeus into making it possible for her to accelerate the birth of Eurystheus and to retard the birth of Hēraklēs, so that Eurystheus the inferior hero became king, entitled to give commands to the superior hero Hēraklēs. In another ancient source, the Herakles of Euripides, we see that Hēraklēs qualifies as the supreme hero of them all, the aristos or ‘best’ of all humans (verse 150; also verses 183, 208, 1306). Still, the heroic superiority of Hēraklēs is canceled by the social superiority of Eurystheus, who is entitled by seniority in birth to become the high king and to give orders to Hēraklēs. Thus Hēraklēs is constrained by the social superiority of Eurystheus and follows his commands in performing āthloi ‘labors’—that is the word at Iliad 19.133.

§24. As we are about to see further in Essay 4, the Labors of Hēraklēs lead to the kleos ‘glory’ that Hēraklēs earns as a hero, and these labors would never have been performed if Hērā, the goddess of seasons, had not made Hēraklēs the hero unseasonal by being born after rather than before his inferior cousin. So, Hēraklēs owes the kleos that he earns from his Labors to Hērā. There are many different kinds of Labors performed by Hēraklēs, as we will see when I analyze the extensive retelling by Diodorus of Sicily (4.8-4.39). One of the Labors of Hēraklēs, as we see from Diodorus, was the foundation of the athletic festival of the Olympics. The story as retold by Diodorus (4.14.1-2) says that Hēraklēs not only founded this major festival: he also competed in every athletic event on the prototypical occasion of the first Olympics. On that occasion, he won first prize in every Olympic event.

§25. This tradition about Hēraklēs is the perfect illustration of a fundamental connection between the labor of a hero and the competition of an athlete at athletic events like the Olympics. As we will see time and again in the essays that follow, the hero’s labor and the athlete’s competition are the “same thing,” from the standpoint of ancient Greek concepts of the hero. The Greek word for the hero’s labor and for the athlete’s competition is the same: āthlos. And our English word athlete is a borrowing from the Greek word āthlētēs, which is derived from this pivotal word āthlos.

See the dynamic Bibliography for Comments on Comparative Mythology.