for 2022.08.22 | By Gregory Nagy

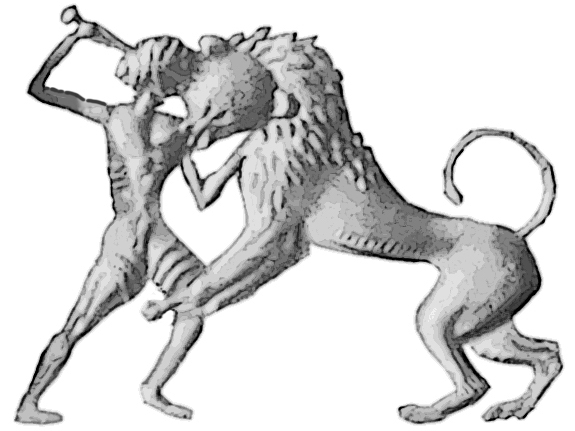

§0. There are Mycenaean phases—more than one Mycenaean phase—to be discovered in myths about the twelve Labors of Hēraklēs, as also in the multitude of further myths that I describe as the sub-Labors of the hero. In Essay 4, I accounted for all twelve of the Labors and for most of the numerous sub-Labors as narrated by Diodorus of Sicily, who as we have seen is dated to the first century BCE. Here in Essay 10 I will comment on some further sub-Labors as narrated by “Apollodorus,” whose Library is dated, as we have also seen, to the second century CE. And, in the course of my commentary, I will be actively comparing these sub-Labors with the twelve Labors. All along, I will keep one general question foremost in mind: are the sub-Labors of Hēraklēs really different from his Labors? In attempting an answer to this question, I will start by focusing on one sub-Labor and on one Labor, both of which are narrated by “Apollodorus.” In the case of the sub-Labor, it is a story that tells how the hero Hēraklēs hunted down and killed with a weapon the Lion of Cithaeron. In the case of the Labor, it is a story that tells how this hero killed with his bare hands the Lion of Nemea by way of a choke-hold—I deliberately use here language conveying both the general idea of free-style wrestling and the specific idea of a combat sport known as the pankration. In the illustration for introducing my essay, I show a drawing based on a picture engraved into a Mycenaean gem, and this picture will turn out to be relevant to my argument, which is, that the stories about the Lion of Cithaeron and the Lion of Nemea both stem from Mycenaean phases—different Mycenaean phases—in the reception of myths about Hēraklēs.

§1. In his book The Mycenaean Origin of Greek Mythology (1932), Martin Nilsson has this to say about the “Greeks” of the first millennium BCE: “Hunting of boar, deer, and other animals was a favorite pastime of the Greeks but was not considered heroic” (p. 218). To be contrasted with this non-heroic model, according to Nilsson, is what we find earlier, in the Mycenaean age, that is, in the second millennium BCE: “It was otherwise,” Nilsson says, “in the Mycenaean age; the Mycenaean gems show very often a man struggling with a lion or a bull” (again p. 218). To help us visualize what Nilsson has in mind, I have shown right away an example of such a gem.

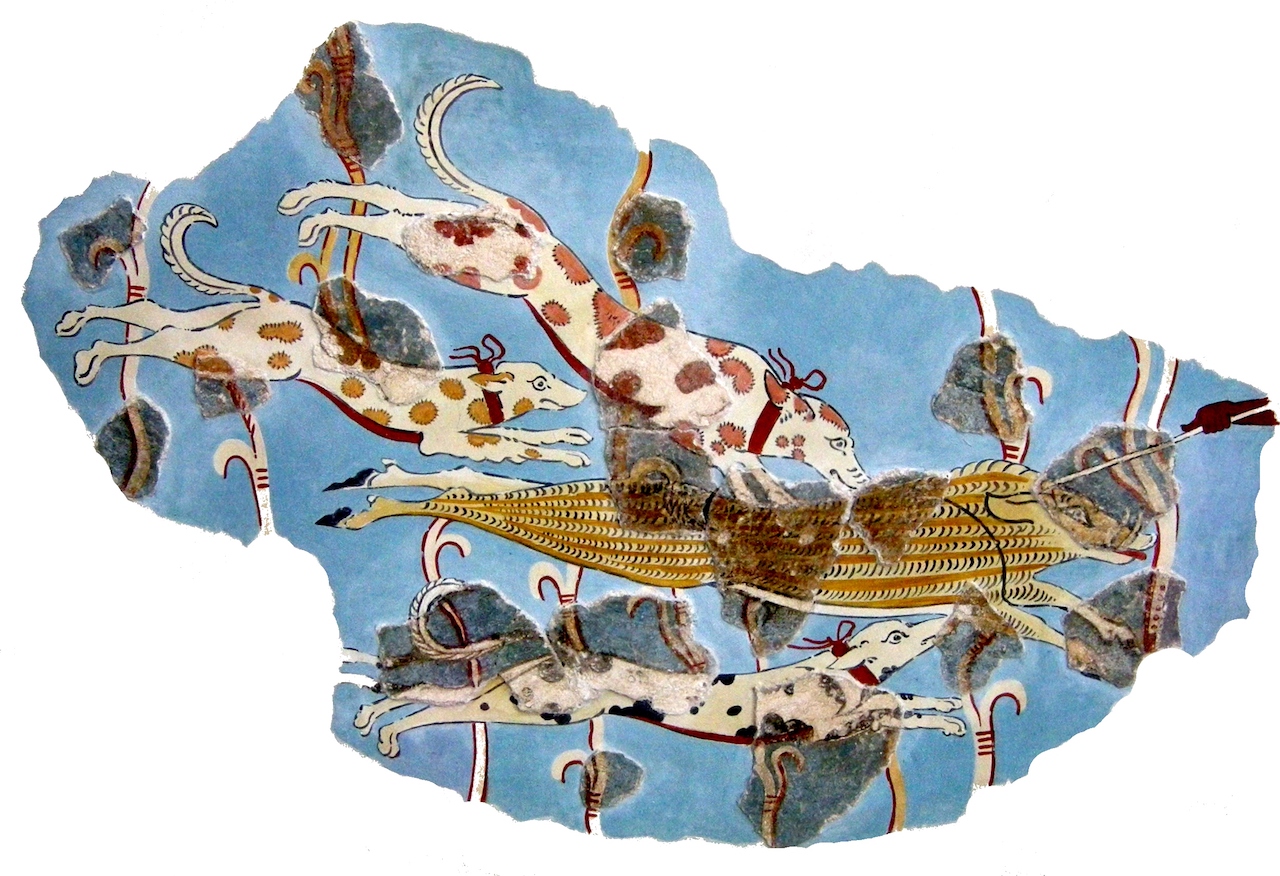

§2. For Nilsson, such a hunting scene would be “heroic.” I agree, and I also agree with the next point that he then makes, which is, that there are similar scenes to be found in other forms of Mycenaean art as well: he speaks of “hunting scenes [… such as] the lion hunt depicted on an inlaid dagger from Mycenae and the boar hunt on a wall painting from Tiryns” (again, p. 218). I show here copies of the two depictions to which Nilsson is referring—both the lion hunt from Mycenae and the boar hunt from Tiryns:

§3. Nilsson goes on to round out his argument by saying: “Mycenaean art corresponds so well to the episodes of Heracles that this coincidence strongly corroborates their Mycenaean origin” (again p. 218; emphasis mine).

§4. In speaking here of a “Mycenaean origin” for such “episodes” that tell the story of the hero Hēraklēs, Nilsson is evidently thinking of two myths in particular, which he mentions from the start (1932: 213): the first myth tells how Hēraklēs killed the Lion of Nemea, and the second, how he captured alive the Boar of Erymanthos. Both these myths are numbered among the canonical Labors of Hēraklēs. In the Library of “Apollodorus,” for example, the myth about the Lion of Nemea comes first in the narrative sequence (2.5.1 pp. 185–187 ed. Frazer 1921 volume I), while the myth about the Boar of Erymanthos comes fourth (2.5.4 p. 195). In the “universal history” of Diodorus, the Nemean Lion is again the first (4.11.3–4) while the Erymanthian Boar is third (4.12.1–2).

§5. Besides the “episode” we read in the Library of “Apollodorus” (again, 2.5.1 pp. 185–187) about the killing of the Nemean Lion by Hēraklēs, we find in the same work another “episode”—another myth—about the killing of another lion by the same hero. And, in this case, the myth is a sub-Labor, not numbered among the canonical Labors of Hēraklēs. In the Library of “Apollodorus” (2.4.9–10 pp. 177–178), this other myth—this sub-Labor—is situated at a markedly early point in the life of the hero, before he even begins his Labors. Here is my paraphrase of the story: Hēraklēs is an adolescent, only eighteen years old, when he hunts down and kills a lion roaming the highlands of Mount Cithaeron near Thebes and Thespiai in Boeotia. The lion had been preying on the cattle in the lowlands. The hero then skins the dead lion and, from this time forward, he wears the lionskin. The scalp of the lion’s entire head has become a makeshift helmet for the hero’s skull, and the face of Hēraklēs is hereafter framed within the gaping jaws of the beast.

§6. I note with interest that this detail about the wearing of the lionskin belongs only to the specific story about the Lion of Cithaeron in the overall story of Hēraklēs as retold by “Apollodorus” (2.4.9–10 pp. 177–178), whereas the specific story about the Lion of Nemea, also retold by “Apollodorus,” has nothing to say about any wearing of a lionskin (2.5.1 pp. 185–187). By contrast, in the overall story as retold by Diodorus (4.11.3–4), the detail about the wearing of a lionskin belongs to the specific story about the Lion of Nemea—but there is in this case no story to be told about that other lion, the Lion of Cithaeron.

§7. So, in this case, the only way for the narrative of Diodorus to include the specific detail about the wearing of the lionskin in his retelling of the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion of Nemea is to occlude altogether the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion of Cithaeron. By contrast, the narrative of “Apollodorus” includes the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion of Cithaeron alongside the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion of Nemea—but it occludes the specific detail about the wearing of the lionskin in the retelling of the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion of Nemea. We see a similar pattern of occlusion in the overall story of the Labors as retold in the metopes at the temple of Zeus in Olympia. The primal scene in the first metope pictures Hēraklēs as a beardless adolescent who has just killed the Lion of Nemea, but he is shown wearing a lionskin neither here nor in any one of the remaining eleven metopes that retell the rest of the story about his twelve Labors.

§8. For Nilsson (1932:208), these two variant myths about Hēraklēs and the Lion are complementary, and both are “Mycenaean” in “origin.” I cannot completely agree. Yes, both variants can be dated back to the Mycenaean era, back to the second millennium BCE. To that extent, I do agree. But I disagree when it comes to “origins.” As I will now argue, we have to make a distinction between relatively earlier and later versions of such myths about Hēraklēs, even within the Mycenaean era.

§9. Reconstructing backward in time, we can posit, as far back as we can go diachronically, a situation where the Strong Man overcomes the Beast. But then, if we now start to reconstruct forward in time, from as far back as we can possibly go, we can detect a pattern of divergence once we reach the Mycenaean era—an era that can be analyzed historically as well as diachronically. When I say “historically” here, I have in mind the distinction I highlighted in the Excursus of Essay 5 between historical and diachronic approaches. For Nilsson, I must add, a “historical” approach includes the evidence of pure archaeology, where no texts are available for analysis.

§10. So, what is the divergence, once we reach the Mycenaean era as we reconstruct forward in time? As I will now argue, the variant myths about the killing of the two lions, one from Nemea and the other from Cithaeron, diverge in the ways they either retain or reshape the traditional mythology: the variant featuring the Lion of Cithaeron is more conservative and thus older, I argue, since it is relatively more exclusive in content, while the variant featuring the Lion of Nemea is more innovative and thus newer, since it is relatively more inclusive.

§11. Here is where the facts of history, broadly understood so as to fold in the facts of archaeology as deployed by Nilsson, are most telling. These facts need to be considered as a vital supplement to the reconstructions achieved through the methods of “comparative mythology” as developed by experts in Indo-European linguistics such as Georges Dumézil, who analyzes, as we have seen especially in Essay 4, the relevant textual evidence in reconstructing backward in time the various myths about a Strong Man in the service of a King.

§12. As we learn from the relevant archaeological evidence assembled by Martin Nilsson in his book on the Mycenaean “origin” of Greek myths (1932), one single fact emerges as all-decisive in its importance for my argumentation here, and I have already formulated this fact in Essay 1. The fact is, we have to reckon with the historical reality of a Mycenaean Empire, which was a loose confederation of kingdoms dominated though not fully controlled by one supreme kingdom, at Mycenae. In the light of this one single fact, which Nilsson has documented in multiple ways throughout his book on Mycenaean “origins,” I can now reformulate what I said earlier about the divergence between the variant myths about the two lions subdued by Hēraklēs.

§13. The variant myth featuring the Lion of Nemea is as I already said more innovative, since it is more inclusive, accommodating different details stemming from different locales. In other words, the Lion of Nemea becomes a better fit for a relatively more centralized mythology emanating from Mycenae. By contrast, the variant myth featuring the Lion of Cithaeron is more conservative, as I argue, since it is more exclusively local and thus less suited to myths that are becoming centralized in the context of an emerging Mycenaean Empire.

§14. When I speak of a relatively more centralized mythology emanating from Mycenae, what I mean is a kind of tolerance, in the process of narrating myth, for including alternative variants, even if some details in the variants will sometimes get occluded—either shaded over or even eliminated. For example, the more inclusive version of the myth about Hēraklēs and the Lion, where the beast is from Nemea, can tolerate other myths about lions, as where the beast is from Cithaeron, but such tolerance can be linked with an occlusion of the detail about the hero’s wearing the skin of the lion.

§15. In this case, I focus again on the version of the myth about Hēraklēs and the Nemean Lion as retold in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (2.5.1 pp. 185–187). The fact that Hēraklēs does not get to wear a lionskin after his first Labor here, which is the killing of the Nemean Lion, is a perfect fit for the centralized mythology emanating from Mycenae. And that is because the command of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, is for Hēraklēs to bring back to him—to the king himself—the skin of the lion. In this version of the myth, then, Hēraklēs must not wear the prize of the lionskin, since it is for the king of Mycenae to decide what to do with such a prize. Moreover, even the hero’s bringing of the lionskin to the king turns out to be threatening. As we read further in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (2.5.1 p. 187), Eurystheus is so insecure about his kingship that he feels threatened after the young hero enters the gate of the citadel of Mycenae in order to make his delivery of the lionskin of the Nemean Lion. The same narrative of “Apollodorus” makes it explicit that Eurystheus now decides to issue a new ruling, after the delivery of the lionskin is made. From now on, the deliveries to be made by Hēraklēs after he completes each new Labor must be deposited outside rather than inside the Gate of Mycenae—which, as we know, is the Lion Gate of Mycenae.

§16. In this same case, we find also a curious link with another Labor of Hēraklēs. In the narrative of “Apollodorus” (again, 2.5.1 p. 187), we read that the royal agent who transmits to Hēraklēs the orders of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae, is a man called Kopreús.

§17. In what follows, I recapitulate the essentials of my relevant commentary in Essay 9. I start again with the obvious, that the name Kopreús is a “talking name.” And the name can mean ‘man of manure [kopros]’. I say “can mean” because the name can also mean ‘man who strikes’ or the like.

§17.1. The role of Kopreus, as the agent of the king Eurystheus in transmitting to Hēraklēs the royal commands to perform Labors, is confirmed in the Homeric Iliad, 15.638–640; in this Homeric context, a son of Kopreus is actually described as ‘Mycenaean’ (638: Μυκηναῖον). As we read further in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (again, 2.5.1 p. 187), this Kopreus became a resident of Mycenae, having been received there as an exile from Elis. And, as we also read in the narrative of “Apollodorus” about another Labor of Hēraklēs (2.5.5 pp. 195–197), Elis was the kingdom of Augeias, whose Stables Hēraklēs had cleared of an immeasurable accumulation of manure produced by countless royal cattle.

§17.2. The detail I have just highlighted from the narrative of “Apollodorus,” about the role of a man from Elis who goes by the name of Kopreus, ‘man of manure’, is another example of centralized mythology emanating from Mycenae, the kingdom of Eurystheus, by contrast with a more localized and thus relatively peripheral myth that is tied to Elis, the kingdom of Augeias. The old identity of this ‘man of manure’ as stemming from the kingdom of Elis, where the manure of the king’s cattle signals a would-be Labor of Hēraklēs, is superseded by the man’s new identity as a resident of the more centralized kingdom of Mycenae, where he becomes the agent of king Eurystheus in giving commands for Hēraklēs to perform one Labor after the next. When king Eurystheus, through the intermediacy of his ‘man of manure’, declares to Hēraklēs that the Labor performed by this hero in clearing manure from the Stables of Augeias, king of Elis, is invalidated and does not really count as a Labor, then the hero must accept the invalidation by the over-king of Mycenae, as we saw in Essay 9.

§18. By now we see emerging in greater clarity a mythological model that is distinctly “Mycenaean.” The Labors of Hēraklēs, as distinct from the hero’s sub-Labors, must all conform to the model of a Strong Man in the service of a King—but this King must be the king of Mycenae, who is the over-king of the Mycenaean Empire, not some localized king within the empire or even outside the empire. Likewise, the Strong Man must be Hēraklēs, not some localized strong man in the service of a localized king. Here it is most important to keep in mind that the killing of the Lion of Cithaeron by Hēraklēs is a service that he renders to two kings other than Eurystheus, and that he undertakes this service before he ever performs any of his canonical Labors—at a time when his name is still generic, Alkeídēs, meaning simply ‘strong man’, as I showed already Essay 4 with reference to the relevant narrative in “Apollodorus” (2.4.12 pp. 183–185). And there is more to say about the two kings who figure in the myth about the hero’s killing of the Lion of Cithaeron, as retold in the narrative of “Apollodorus” (2.4.9–10 pp. 177–179). One of these two rulers is Amphitryon, king of Thebes in Boeotia and the mortal counterpart of immortal Zeus in the myths about the fathering of Hēraklēs, while the other ruler is Thespios, king of Thespiai, also in Boeotia, whose fifty daughters were all impregnated, one night after the next, during the fifty days-and-nights of service rendered by our hero to the two kings (this part of the myth, about the fifty impregnations, is also attested in the otherwise curtailed narrative of Diodorus 4.29.23). Hunt by day, impregnate princesses by night.

§19. Returning to my overall argument here—that the services rendered by Hēraklēs to kings can be counted as canonical Labors only if these services are ordered by Eurystheus, king of Mycenae—I note once again that even a canonical Labor can be subject to invalidation if any king other than Eurystheus is also involved, as we saw in the case of the Labor involving simultaneously Augeias, king of Elis, and Eurystheus, king of Mycenae. Since Eurystheus was over-king of the Mycenaean Empire, he and he only was the king who actually gave the orders for our Strong Man to clear the Stables of Augeias. As I emphasized already in Essay 4, where I forward-reconstructed the “Indo-European” model of “Strong Man in the service of King,” the Strong Man must obey the king’s orders, no matter what, since these orders are divinely authorized. If the Strong Man does not obey, in terms of such an “Indo-European” mythological model, such disobedience—or even any sign of hesitation—is deemed to be a “sin.” In Essay 4, I have already pointed to the backward-reconstructions of Georges Dumézil concerning various such “sins” committed by a generic Strong Man in the service of a generic King, as attested especially in Germanic as well as Greek myths.

§20. But now we come to a new question about the Labors of Hēraklēs in the service of Eurystheus, king of Mycenae. As we reconstruct these Labors forward in time, from as far back as we can go, are we to say that our reconstruction has recovered an “Indo-European” model of mythmaking, or should we instead simply restrict our field of vision to a Mycenaean model? My answer is divided into four parts:

§20.1. The first part is relatively uncomplicated. As I have already shown, both the earlier “Indo-European” and the later Mycenaean models of mythmaking are represented in narratives about the actual āthloi—as the ‘Labors’ of Hēraklēs are consistently called in the retellings of both Diodorus and “Apollodorus.”

§20.2. But there are complications. The Mycenaean models of mythmaking have evidently integrated also other models that were not Indo-European in derivation, and such integration took place in the overall context of a long-lasting and all-pervasive cultural interconnectedness between the Mycenaean Empire and the earlier Minoan Empire originating from the island of Crete. The Minoan-Mycenaean cultural continuum was in turn strongly influenced by extensive contacts with other civilizations, especially in the Near East and in Egypt. And most of these civilizations, with the prominent exception of a cultural continuum represented by languages like Hittite and Luvian in Asia Minor, were represented by populations that spoke non-Indo-European languages.

§20.3. There are further complications. As we have already seen, the so-called sub-Labors of Hēraklēs can also follow, like the Labors, a Mycenaean model of mythmaking. A shining example is the myth about the hero’s killing of the Lion of Cithaeron, narrated in the Library of “Apollodorus” (2.4.9–10 pp. 177–178), which counts only as a sub-Labor by contrast with the myth about the same hero’s killing of the Lion of Nemea, also narrated by “Apollodorus” (2.5.1 pp. 185–187), which counts as a full-fledged Labor. Here we have the advantage of being able to compare the sub-Labor and the Labor as they coexist within one integrated narrative, and the comparison shows one big difference: the detail about the wearing of the lionskin by the hero Hēraklēs in the narrative about the sub-Labor differs from the detail about the presentation of the lionskin as a prize to the king Eurystheus in the narrative about the Labor. When we compare these two coexisting myths about the Lion of Cithaeron and the Lion of Nemea in the narrative of “Apollodorus” with the single unified myth about the Lion of Nemea in the narrative of Diodorus (4.11.3–4), it is the sub-Labor and not the Labor in the narrative of “Apollodorus” that matches more closely the Labor in the narrative of Diodorus. From a comparative point of view, then, the detail about the wearing of the lionskin has less to do with the “Indo-European” model of foregrounding the service of a Strong Man to a King—and has more to do with a Mycenaean model of identifying the generic hunter with the generic beast that he is hunting. In what follows, I will elaborate on such a Mycenaean model. For now, however, it is enough for me to add that such a model could still allow for fusion with an “Indo-European” model where the Strong Man presents his King with a prize, as evidenced in the version of the story as retold by “Apollodorus,” where Hēraklēs presents Eurystheus with the lionskin of the Lion of Nemea (again, 2.5.1 pp. 185–187).

§20.4. And there is still one more complication that I must confront here, at least in a preliminary way. It appears, from what we have seen so far, that the sub-Labors of Hēraklēs as narrated by Diodorus and “Apollodorus” could also be explained—much like the Labors of these narrations—in terms of an “Indo-European” model of mythmaking. A case in point is the myth about the clearing of the Stables of Augeias. As we saw in Essay 9, the relationship between Hēraklēs and Augeias, king of Elis, is at least in some ways parallel to the relationship between Hēraklēs and Eurystheus, king of Mycenae. Such parallelisms, then, can be analyzed as a reflex of “Indo-European” elements in the mythological tradition about Hēraklēs and Augeias, and these elements are so old that they cannot yet fully reflect, as a reality, the emergence of Mycenae as the centerpoint of what I have been describing here as a Mycenaean Empire.

§21. Before I can bring this essay to a close, I need to circle back, one last time, to what I described at the beginning as a Mycenaean phase in the reception of myths about the sub-Labors as well as the Labors of Hēraklēs. Such a Mycenaean phase is relevant to my suggestion at §20.3 with reference to the mythological detail about the wearing of the lionskin by Hēraklēs. From a comparative point of view, I suggested, this detail has less to do with “Indo-European” models—and has more to do with a distinctly Mycenaean model, where the generic hunter identifies in some way with the generic beast that he is hunting. Here I will elaborate on this model, which turns out to be not merely “Mycenaean” but more properly “Minoan-Mycenaean” in its synthetic prehistory. And, given that non-Indo-European elements as transmitted by Minoan civilization got to be synthesized with whatever Indo-European elements were at least partly inherited by Mycenaean civilization, it is better for me at this point to shift the terminology: instead of describing such synthesized Minoan-Mycenaean mythological models as “Indo-European” I will use instead a more appropriate term, “Aegean.”

§22. Relevant evidence has been collected by Janice L. Crowley (2010) in an article bearing a most evocative title, “The Aegean Master of Animals: The Evidence of the Seals, Signets, and Sealings.” The seals, signets, and sealings to which Crowley is referring here are the “gems” to which Nilsson was refering in general (1932:218), as I noted at the beginning of this essay. For further study of these seals, signets, and sealings, I recommend a most useful website hosted by Crowley: http://www.iconaegean.com.

§23. With regard to these “gems,” I have quoted already at §1 what Nilsson (1932) had to say: “the Mycenaean gems show very often a man struggling with a lion or a bull” (p. 218). He went on to say, as we saw in §1: “Mycenaean art corresponds so well to the episodes of Heracles that this coincidence strongly corroborates their Mycenaean origin” (again p. 218; emphasis mine). And I already showed, at the beginning of this essay, a Mycenaean gem bearing the carved image of such a Herculean struggle with a lion. What we saw pictured there was a hunter in the act of choking with his left hand the hunted beast while he is holding a dagger, raised high, with his right hand, This dagger, I think, will be used to skin the lion once it is killed.

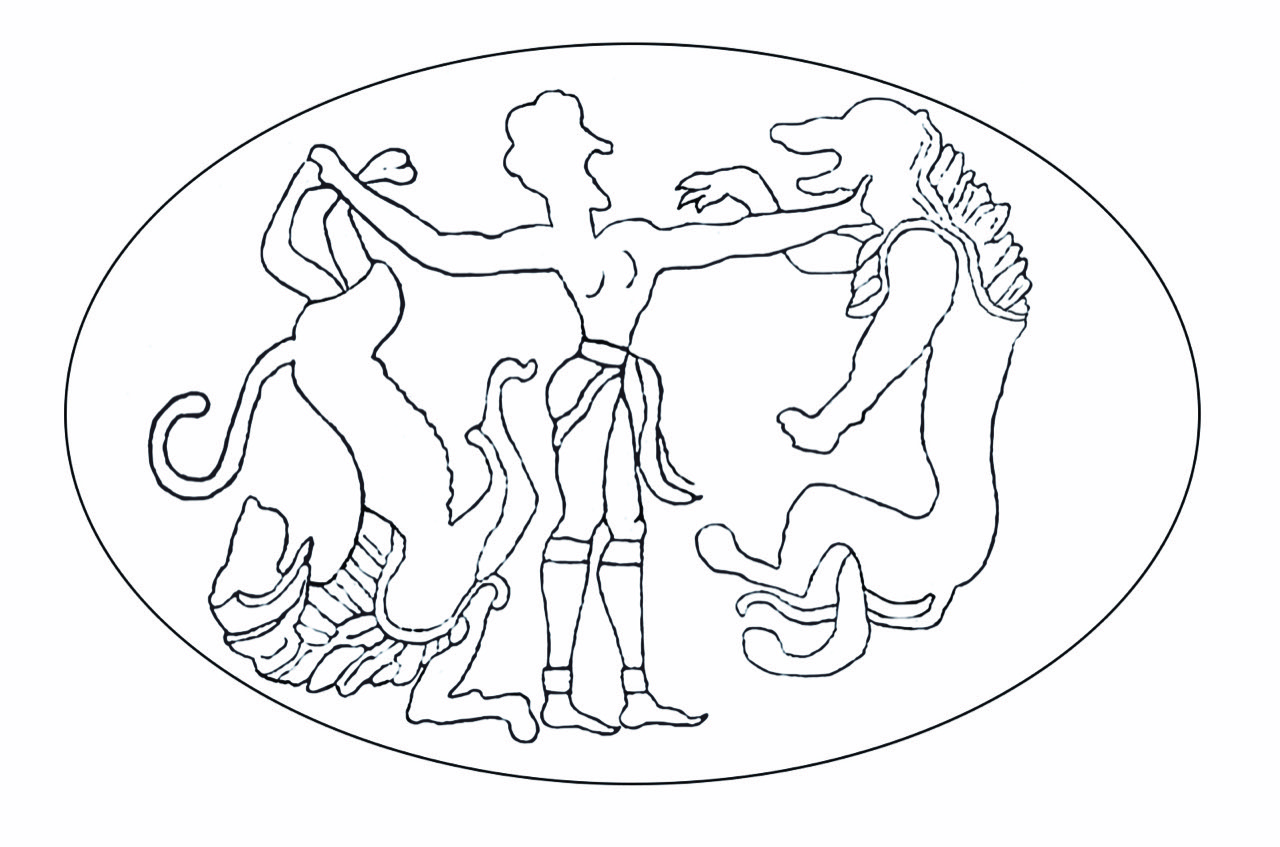

§24. The article of Crowley (2010), however, deals with a different kind of image, which I will now argue is also relevant to “episodes” involving Hēraklēs. Her article shows several examples of this different kind of image, but I will limit myself here to showing only the first example that she adduces, Figure 1 (CMS I 89). Once again, we see here an image carved into a Mycenaean gem—this time, it is a jasper signet ring. Like the gem I showed at the beginning of this essay, this gem too was actually excavated at Mycenae:

§23. Unlike the gem I showed at the beginning of this essay, the gem I show now pictures the struggle with wild animals differently. We now see a weaponless and barehanded domination of lions. The human protagonist in this image is what Crowley (2010) calls, aptly, the generic “Aegean Master of Animals.” Here is her description of the image (p. 77):

The human figure is depicted in the Aegean combination pose, head in profile with the upper torso frontal and swiveled at the waist to render the lower torso in profile, the regular pose for Master figures. He is depicted as a muscled man clothed in belt and kilt and so full of power that he holds both lions clear of the ground, one by the neck, the other inverted and suspended by a hind foot with head regardant.

§24. Crowley (2010) then proceeds to show and to analyze several other carved images of this Aegean Master of Animals, seen in the act of dominating either two lions or various pairs of other animals. Another such image of the Master, once again seen in the act of dominating two lions, shows him in the role of a Mycenaean warrior and hunter. Here is the description by Crowley (p. 80):

The Lion Master here [Figure 12 = CMS Vi 313] wears a straight gown or tunic covering his body to the knees and thus giving a distinctly different shape to the Minoan cinched-in waist. He also wears the boar’s tusk helmet of the Mycenaean warrior and hunter.

§25. To clarify “the Aegean persona” of our “Master of Animals,” I now quote an apt formulation by Crowley (2010:88) about a reshaping, in a Mycenaean world representing the “West,” of an earlier Minoan model that is strongly influenced by analogous models stemming from an alternative world representing the “East” that we know as the Near East:

The many and varied representations on the [Mycenaean] seals, this most endemic Aegean art form, are the clearest indicators of the Master’s happy domicile in the West. He carries forward much of the iconography of earlier Near Eastern motifs, but he has also acquired distinctively Aegean characteristics. He has new Aegean names since he has gained new Aegean animal attendants [besides the lion, primarily]: the Minoan [“]genius[”], the Cretan agrimi, the dolphin, hound, and stag. His metamorphosis into the athletic Minoan male is seen in most portrayals, but he may also be a Mycenaean warrior-hunter, a [“]genius[”], a hybrid human, or deity Lord. […] It is a pity that the absence of textual gloss prevents us from calling the master by his Aegean name.

§26. In at least some details, I propose, the name of Hēraklēs is suited to the Aegean Master of Animals. The picturing of the Master’s weaponless and barehanded domination of wild animals seems to me parallel to what we find in some “episodes,” as Nilsson had called them, that are recounted among the Labors of Hēraklēs—where our Strong Man hunts down the animals but then “brings them back alive,” as in the case of the Erymanthian Boar. This beast is captured alive and delivered alive to Eurystheus by Hēraklēs, as we read in the narratives of Diodorus (4.12.1–2) and “Apollodorus (2.5.4 pp. 191–193). In this case, I should add, it is relevant that the boars as well as the deer that roam Mount Erymanthos are described in Odyssey 6.102–104 as the favorite animals of Artemis, goddess of the hunt, who in turn reminds me of the Mistress of Animals as described by Crowley (2010:85–87) in her survey of carved seal-images picturing a goddess who dominates animals in poses that are in some details parallel to the poses of the Master.

§27. Also, in general, the picturing of our Master of Animals as a manhandler of lions seems to me parallel to what we find being narrated in some of the “episodes” about the Labors of our Strong Man. In particular, I have in mind the moment when Hēraklēs subdues the Nemean Lion by choking it to death in a free-style wrestling hold. In the narratives about this Labor, as we have seen, the weaponless and barehanded subduing of the Lion by the Strong Man actually results in the death of the beast—which in turn results in the wearing of the lionskin by Hēraklēs, at least in some versions of the Labor. Such wearing of the lionskin is what I have had in mind all along when I referred to the idea of a hunter’s identification with the hunted beast.

§28. A comparable identification of Hunter with Hunted takes place in the narrative about the killing of the Lion of Cithaeron. Like the Boar that roams the highlands of Mount Erymanthos and ravages the lowlands of Arcadia according to the story as retold by “Apollodorus” (2.5.4 p. 195), the Lion roams the highlands of Mount Cithaeron and preys on the cattle pasturing in the lowlands of Boeotia according to an earlier parallel story as retold, again, by “Apollodorus” (2.4.9–10 pp. 177–179). I now paraphrase for the second time, repeating from §3, exactly what happens when our Strong Man enters the scene. He is not yet called Hēraklēs, and he is still an adolescent, only eighteen years old, when he hunts down and kills the Lion in this story as transmitted by “Apollodorus.” The youthful Strong Man then skins the dead lion and, from this time forward, he wears the lionskin. I repeat my initial description. The scalp of the lion’s entire head has become a makeshift helmet for the hero’s skull, and the face of the hunter is hereafter framed within the gaping jaws of the beast that he has hunted down and killed. Such a Mycenaean story about a sub-Labor performed by our Strong Man is a good fit, I propose, for earlier Aegean stories, now lost, about the Minoan-Mycenaean Master of Animals.