2023.09.29 | By Olga M. Davidson

This pre-edited standalone essay is presented in honor of Pierre Judet de La Combe, whom I first met, together with Greg, in September 1975, almost half a century ago, at the apartment of Jean and Mayotte Bollack in Paris. Among the young classicists there at the happy time of our meeting our dear friend Pierre was another of our dear-friends-to be, Philippe Rousseau. This essay is a fond evocation of those happy memories and a modest tribute to the intellectual and personal dynamism of Pierre.

Xerxes was ruler of the Persian Empire from 486 to 465 BCE. Under his rule, the empire was by far the mightiest power in the ancient world, dominating Asia Minor, the East Mediterranean, Egypt, the Near East, and Central Asia.

The fame of this ruler is occluded, however, in Greek sources, especially in the poetry of Aeschylus and in the prose of Herodotus, both dating from the fifth century BCE, whose narratives concentrate on the failure of Xerxes in his plan to subjugate the Hellenes inhabiting the mainland of the East side of the Aegean Sea. But the fame of Xerxes is occluded also in Persian sources, especially as represented in the medieval Persian epic of Fedowsi, the Shahnama or ‘Book of Kings’, composed in the late tenth and early eleventh century CE. In this case, however, the occlusion is compensated by way of a transfer of credit, as it were, from one Iranian king to another, that is from Xerxes, a prominent warrior-king figure of the Achaemenid dynasty, to Khosrow, a comparably prominent warrior-king figure of the Keyānid dynasty.

Before I delve into the occlusion and the transfer of credit, as I just called it, I start with the credit itself, as reported in Iranian sources.

The Persian name of Xerxes was spelled in the Old Persian cuneiform script as x-š-y-a-r-š-a, meaning “he who rules over warriors.” In presenting my findings about the exalted status of Xerxes as warrior-king, I build on the earlier findings of Parivash Jamzadeh in a study of two Achaemenid inscriptions glorifying the Persian king Xerxes who ruled the Achaemenid Empire from 486 to 465 BCE. The texts of these two inscriptions concentrate on the status of Xerxes when he was still only a crown prince, son of Darius the Great. As Jamzadeh shows, the themes and the language of these two inscriptions concerning Xerxes as a crown prince are shaped by a poetic tradition that survives into the era of New Persian poetry as represented by the Shahnama of Ferdowsi. In her study about the episode about Key Khosrow in the Shahnama, Jamzadeh shows that the status of crown prince is likewise what is at stake in the narrative of this episode. In effect, Key Khosrow is competing for the status of crown prince (Shahnama III 233-234), and the testing place for Key Khosrow and his competitor, a prince named Fariborz, is a fortress inhabited by demons (Shahnama III 236-241).

I quote here my own translation of the relevant episode about Key Khosrow in the Shahnama of Ferdowsi. What this episode shows is that Key Khosrow is a substitute, as it were, for Xerxes himsef as a warrior-king:

When he was near the fortress he mounted up, / put on his mail and belted it. / From on high, he called for a scribe /and ordered him to write a letter most eloquent and royal of style / with ambergris, and in Pahlavi: / “This letter comes from the Almighty’s slave— / From noble Key Khosrow, the world-seeker, / who, escaped from evil Āhriman’s bondage, / and who, with the help of God, has washed his hands from all evil. / God, who is eternally the Lord, most high, / the giver of all things good, our guide, / the Lord of Mars, of Saturn, and the Sun, / the Lord of Grace (farr), the Lord of Strength, / who gave the throne and Grace (farr) of kings to me, / and fierce lions’ claws and elephantine body (piltan). / The whole world is my kingdom, all is mine, / from Pisces downward to the Bull’s head. / If this fortress be in the province of Āhriman, / the enemy of the World-Creator, / I by the Grace (farr) of holy God, and by his command, / will smash it all into the dust with my mace. / And if it is a den filled with magicians / I alone can get rid of them without an army, / For when I throw my leather lasso / I will capture the heads of magicians in my noose. / And if the blessed Sorush himself is here / The army will be united as one under the command of God. / I am indeed not of the seed of Āhriman; / My soul has Grace (farr), my body has stature and elegance. / By God’s command I will reduce this fortress to nothing, / Such is the message of the king of kings.” / Khosrow then seized a spear with his hand / And bound the letter to the tip of that spear; / He raised the spear straight up like a banner. / He asked for nothing on earth save Grace (farr), / and ordered Giv to hasten with the spear / and stride up to the lofty walls. / He said to him: “Take this letter of admonition,/ And bring it to the wall of the lofty fortress. Plant there the spear, call on the name of God, / then quickly turn around and hurry back.” / That worshipper of God, that glorious chief, / Giv, took the spear in hand and went his way, / Filled with blessings from the best of souls, the worshipper of God, / he set the letter by the wall, / And delivered the message of Khosrow, / He uttered the name of God who bestows Good / And fled on a fast horse like the wind. / That noble letter vanished. / There was big clash, dust flew, and the fortress erupted (bar damid). / At the same time by command of Holy God / the walls of the fortress cracked apart. / You would say: “It was a thunderstorm in spring.” / A clamor rose up from the plain to the mountaintop. / The earth became black as a black man’s face. / What of the walls of the city, what of the army? / You would say “A dark cloud has come, / The surrounding air is like a mighty lion’s maw. / Then Key Khosrow urged on his black horse, / And shouted to the captains of the army: / “Make arrows rain in showers upon the fortress, / make the air be like a cloud in spring.” / Immediately a fog rose laden with hail, / A cloud that brings on a hail of death / Many div-s met their death by these arrows / And many fell to earth, with all sources of courage decimated. / After a while, a brilliant light began to shine, / And all the heavy darkness vanished completely. / The world became like the shining moon, / by the name of God, there was victory for the Shah / A wonderful breeze sprang up;/ the heaven above and all the face of earth began to smile. / The div-s left at the command of the Shah. / The entry of the fortress appeared in the center. / The Shah of the Free entered from there / with old Gudarz, the offspring of Kishwād. / He saw a city inside that large fortress, / full of gardens, plazas, halls, and palaces. / On that spot where that brilliant light had first shone, / where there was no longer any trace of the fortress, / Khosrow decreed that in that very place, / there be a dome, reaching up to the dark clouds. / It was ten lassos long and wide, / Encircled by high vaulted chambers. / Its periphery was to be half a rapid Arab steed’s course. / He brought and placed there (the fire of) Āzargashasp, / And round it sat the mōbad-s. / Astrologers, and the men of wisdom. / He stayed in that city for as much time it took / for that Fire-temple (Atash-kadeh) to attain to good reputation (good aroma and color). / When a year had passed, he prepared his army for departure, / Having packed up all his goods, and getting all to mount up.

As we can see from the text of this episode as I have translated it, the key to the success of Key Khosrow is his farr. His rival, Fariborz, does not have farr, and that is why he fails when the first attempt is made to capture the fortress of demons. But then it is the turn of Key Khosrow. At the climax of this episode (Shahnama III 243-245), Key Khosrow dictates what is described as a ‘letter’, which he attaches to a spear, sending his companion Giv to plunge it into the base of the wall surrounding the fortress. As we can see from the text as I have translated it, the words of the ‘letter’ dictated by Key Khosrow are quoted by the poetry of Ferdowsi, and, as Jamzadeh argues persuasively, these words are comparable with the wording of an Achaemenid inscription “quoting” the words of the crown prince Xerxes. I quote here the most relevant part of that wording:

Other sons of Darius there were – thus for Ahuramazda was the desire – but Darius my father made me greatest after himself. When my father Darius went away from the throne, by the will of Ahuramazda I became king on my father’s throne.

XPf 15-25 via Kent 1953:150

In another Achaemenid inscription, also noted by Jamzadeh, Xerxes is quoted as saying, and I quote again:

There was a place where previously false gods [daivā] were worshipped. Afterwards, by the favor of Ahuramazda, I destroyed that sanctuary of the demons, and I made the proclamation: “the demons shall not be worshipped.” Where previously the demons were worshipped, there I worshipped Ahuramazda and Arta reverently.

XPh 35-41 via Kent 1953:151

Just as Xerxes converts a ‘sanctuary of demons’ into a precinct of correct worship, so also Kay Khosrow converts the fortress of demons into a holy city that is centered on the Fire of Goshnasp, known as Ādur Gushnasp in the older language of Pahlavi. Here I cite again the relevant lines of the Shahnama:

On that spot where that brilliant light had first shone, / where there was no longer any trace of the fortress, / Khosrow decreed that in that very place, / there be a dome, reaching up to the dark clouds. / It was ten lassos long and wide, / Encircled by high vaulted chambers. / Its periphery was to be half a rapid Arab steed’s course. / He brought and placed there (the fire of) Āzargashasp, / And round it sat the mōbad-s. / Astrologers, and the men of wisdom. / He stayed in that city for as much time it took / for that Fire-temple (Atash-kadeh) to attain to good reputation (good aroma and color).

I should emphasize that the wording of the Shahnama indicates that this aetiological narrative about the institution of the Fire of Goshnasp stems from a West Iranian tradition, centered in Pars, just as the narratives of the comparable Achaemenid inscriptions are of course West Iranian by origin, centered in Pars. As Jamzadeh emphasizes, the point of departure for the action of the episode about the conquest of the fortress of demons by Key Khosrow is pointedly specified as a place named Estakhr, which is in Pars (Shahnama III 236.3576), and, just as pointedly, the narrative specifies that Key Khosrow returns to Pars after he spends a year in performing the sacred task of building and maintaining the new city that centers on the Fire of Goshnasp (Shahnama III 236.3755). So the spatial frame for the entire narrative is Western Iran.

Here I turn to the two Greek sources, already mentioned, about Xerxes,

The earlier of these two sources is a tragedy known as The Persians, the premiere of which was performed in the year 472 BCE at the festival of the City Dionysia in the city of Athens. This tragedy was composed and directed by the Athenian state poet Aeschylus and sponsored by the most celebrated exponent of Athenian democracy at that time, Pericles himself. Ιn the Frogs of Aristophanes, performed in the year 405 BCE, the stage-Aeschylus brags (verse 1027) that the best ergon or ‘work’ he ever created was this tragedy, The Persians.

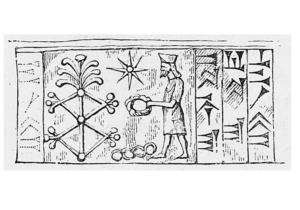

The second and later source is the History of Herodotus, which first circulated in the Greek- speaking world during the last decades of the fifth century BCE. I concentrate here on just one relevant point in his narrative about Xerxes. The historian reports (7.21) that Xerxes, at the beginning of his expedition against the Hellenes on the other side of the Aegean Sea, finds a plane tree that enthralls him with its beauty: he treasures this tree so dearly that he decorates it with gold ornaments and arranges for it to be guarded by one of his elite troops known as the Immortals. A later Greek author, Aelian (Varia Historia 2.14), ridicules Xerxes for idolizing a tree, but this worshipful gesture of the king is in fact true to the royal traditions of his dynasty. As Pierre Briant, an expert in the history of the Persian Empire, points out, the kings of the Persian empire could be pictured as worshipping the plane tree as a tree of life.

Seal of Xerxes. Perrot & Chipiez 1890 fig. 497, via Briant 2002 fig. 30.

This act of adoration is reproduced at the beginning of an opera by Handel. Although Handel’s Xerxes differs from the historical emperor in many ways, they are both men given to intensely passionate acts, as we see and hear in the breathtaking aria, “Ombra mai fu.”

Frondi tenere e belle

del mio platano amato

per voi risplenda il fato.

Tuoni, lampi, e procelle

non v’oltraggino mai la cara pace,

né giunga a profanarvi austro rapace.

Ombra mai fu

di vegetabile,

cara ed amabile,

soave più.

O leaves tender and beautiful

of my beloved plane tree

On you may fate shine resplendent

May thunder, lighting, and storms

never intrude, ever, on your dear peace of mind,

nor may there be any wind that comes to violate you

—some violent wind from the west.

Shade there never was

of any plant

so dear and lovely

or any more sweet.

Trans. Gregory Nagy

As the seal of Xerxes shows, his veneration of the Tree of Life, which for him is a plane tree that grows in the Greek-speaking territory of Asia Minor, is an overarching symbol of his ambition as king of a multi-ethnic Persian Empire. But the king’s failure on the West side of the Aegean Sea has led to an occlusion of his imperial ambition—to be replaced by the ambitions of other Persian kings, all devotees of the Tree of Life.

Bibliography

Briant, P. 2002. From Cyrus to Alexander: A History of the Persian Empire. Translated by Peter T. Daniels. Winona Lake IN.

Dhalla, M. N. 1965. The Nyaishes or Zoroastrian Litanies. New York.

Jamzadeh, P. 2004. “A Shahnama Passage in an Achaemenid Context.” Iranica Antiqua 39:383-388.

Kent, R. G. 1953. Old Persian: Grammar, Text, Lexicon. New Haven.

Ketterer, R. C. 2015. Laughing at the Great King: Ottomans as Persians in Minato’s Xerse (Venice 1654). Abstract. Abstracts for 2015 CAMWS Meeting.

Perrot, G, and C. Chipiez. 1890. Perse: Phrygie—Lydie et Carie—Lycie. Vol. 4 of Georges Perrot and Charles Chipiez, Histoire de l’Art dans l’Antiquité. Paris.