2025.07.23 | By Gregory Nagy

This essay is a pre-edited version of an article intended for an encyclopedia. I am grateful to my colleagues Keith DeStone and Claudia Filos for their most valuable help with this project.

§1. Crates of Mallos was a philologist and textual critic who was head of the Library of Pergamon in the second century BCE. There is a definitive edition, by Maria Broggiato (2001), of all the fragments surviving from the works of Crates, including testimonia (for previous editions, which do not strive for completeness (see Broggiato pp. lxviii–lxix; on the life of Crates, see her pp. xvii–xix). In the essay here, the opening comments are epitomized from a review of this important work on Crates (Nagy 2007).

§2. In the ancient world, Crates was best known for his interpretations of the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey, but he was also well known for his theories in the fields of astronomy and geography. The wide-ranging intellectual interests of Crates are most helpfully surveyed and documented in the thoroughgoing work of Maria Broggiato (2001). Besides the accomplishments of Crates in his research on Homer, which included his pioneering insights on the geography of Earth as a globe, Broggiato keeps track of fragmentary evidence concerning related accomplishments of his, including his commentaries on other ancient authors such as Hesiod and Euripides. As a Homeric scholar, he was a rival of Aristarchus of Samothrace, who was head of the Library of Alexandria around the same time, the second century BCE. There are many traces, especially in the Homeric scholia, of rival Homeric readings and interpretations attributed to these two scholars, who evidently engaged in a lively ongoing exchange with each other in their writings.

§3. Thanks to the painstakingly complete and philologically precise collection of the relevant evidence by Broggiato, classicists can now trace the intellectual history of the differences between Crates and Aristarchus. In the ancient world, the many real differences between these two rival editors of Homer were conventionally reduced to a single overarching contrast between Crates the Pergamene as an “anomalist” and Aristarchus the Alexandrian as an “analogist.” Such an antithesis, as the evidence collected by Broggiato shows decisively, has been grossly exaggerated.

§4. It cannot be denied, however, that Crates had major differences with Aristarchus in his own work on Homer. A most prominent example is Crates F 20 (throughout this article, I follow the numbering of Broggiato for both the fragments, abbreviated F, and the testimonia, abbreviated T). We read in Plutarch, De facie in orbe lunae 938d:

ἀλλὰ σύ, τὸν Ἀρίσταρχον ἀγαπῶν ἀεὶ καὶ θαυμάζων, οὐκ ἀκούεις Κράτητος ἀναγινώσκοντος

Ὠκεανός, ὅσπερ γένεσις πάντεσσι τέτυκται (Iliad 14.246)

ἀνδράσιν ἠδὲ θεοῖς, πλείστην ‹τ᾿› ἐπὶ γαῖαν ἵησιν. (Iliad 14.246a)

But you are always so enamored of Aristarchus and so impressed with him that you do not hear [akouein] Crates as he reads-out-loud [anagignōskein]:

… Ὠκεανός [Ōkeanos], who has been fashioned as genesis for all

men and gods, and he flows over the Earth in all her fullness.

The first of these two verses as quoted by Plutarch corresponds to Iliad 14.246—with verse-initial Ὠκεανοῦ, continuing the syntax of verse 245 as we have it—while the second, “14.246a,” has been omitted from the text proper of modern editions of the Iliad. Evidently, the base text of Homer as established by Aristarchus excluded this verse, while the base text as established by Crates included it.

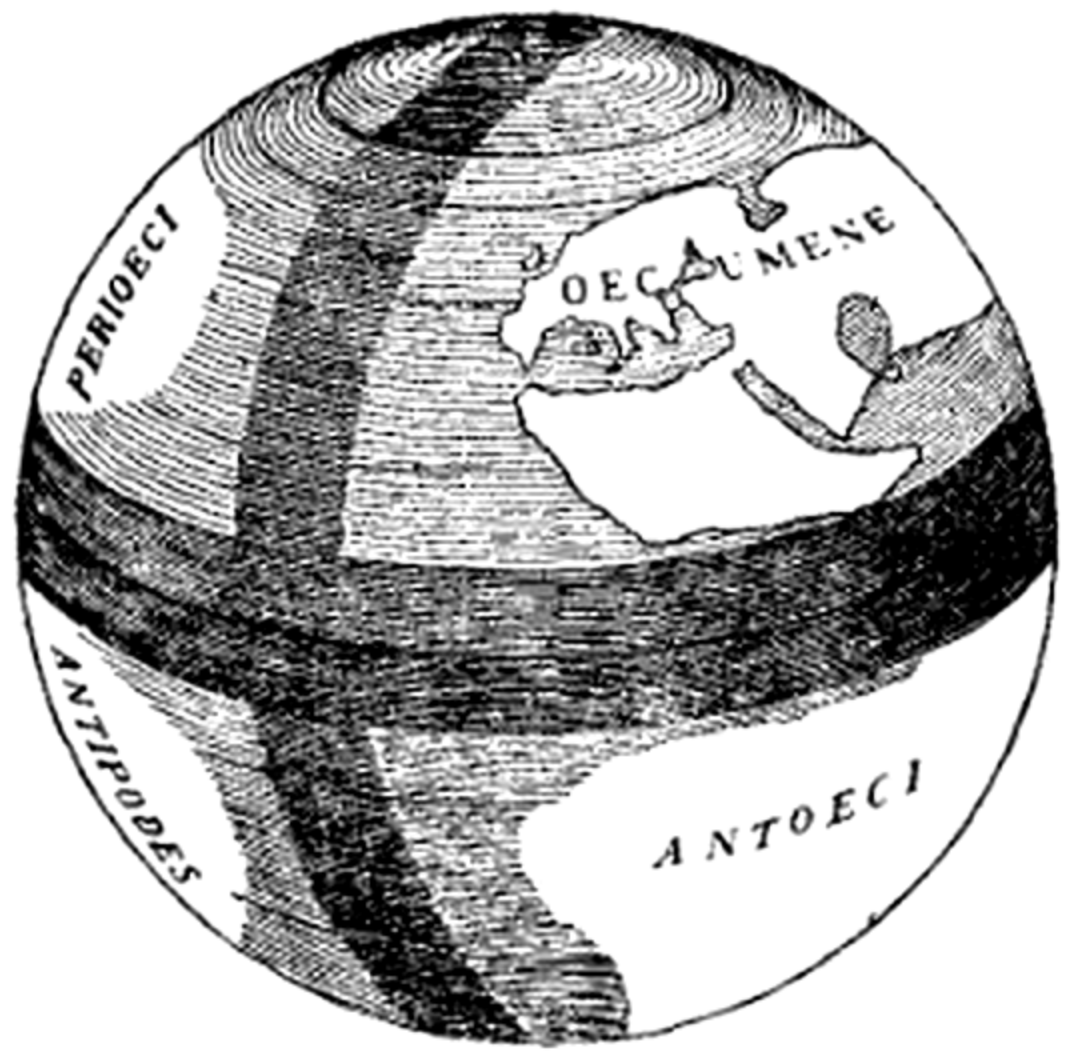

§5. For Crates (F 20), the verse of Iliad 14.246a provided evidence for a cosmic theory—that the Okeanos was the salt-water “ocean” covering the earth, which was supposedly spherical. According to the theory of Crates, the earth was spherical, at the center of a universe that was likewise spherical (Broggiato p. lii). Crates evidently interpreted πλείστην … ἐπὶ γαῖαν in a modernizing sense: ‘[which flows] over most of the earth’. In other words, the salt-water ocean covers most of the spherical earth. This theory was opposed by Aristarchus, who viewed the Homeric Okeanos as a fresh-water river surrounding an Earth that is round and flat (Broggiato p. 179).

§6. We may often wish to disagree with specific points of interpretation made by Crates, but the textual variants that he adduces cannot be dismissed as mere inventions. From an analysis of the formulaic composition of Iliad 14.246a, for example, we can see that there is nothing non-Homeric per se about the form of this verse as adduced by Crates (Broggiato p. 179 n. 151, with reference to Iliad 13.632 and two other Homeric passages). Nor is there anything non-Homeric per se about the contents. Moreover, from a formulaic point of view, the verse does not even necessarily convey a vision of a salt-water ocean—let alone a spherical earth, as argued by Crates.

§7. From the standpoint of Homeric poetry as a formulaic system, the mythological essence of Okeanos as a divinity is self-evident: he is a cosmic fresh-water river-god who circles the goddess Earth, pervading her with fresh-water springs that he sends up mysteriously from below (see esp. Iliad 21.195-197). Restating this essence in a depersonalized way, we may say that the earth is irrigated all over its surface by an upward flow that emanates ultimately from this cosmic earth-encircling river Okeanos. From the standpoint of Homeric poetry, then, the phrase πλείστην … ἐπὶ γαῖαν at Iliad 14.246a can be interpreted as ‘[who flows] throughout the Earth in all her fullness’.

§8. Even so, from the standpoint of Homeric criticism, the editorial decisions of Crates reflect a solid grounding in the textual evidence. Another striking example, to be analyzed further below, is Crates F 1 (as analyzed by Broggiato pp. 140–141), about the beginning of the Homeric Iliad.

§9. Scholars of the Library of Pergamon, most notably Crates, preferred to think of themselves as kritikoi (Pfeiffer 1968:159, 238, 242; Nagy 2024 §4). According to Crates, a kritikos had to be master of the entire ‘science’ (epistēmē) of logikē, while a grammatikos, exemplified by Aristarchus, head of the Library of Alexandria, was supposedly confined to explaining questions of vocabulary and prosody. Our primary source here is Sextus Empiricus, Adversus mathematicos (1.79). As we also learn from Sextus (1.248), who cites as his source a student of Crates by the name of Tauriscus, the grammatikē of the Alexandrians was subordinate to kritikē, which was a far broader concept that encompassed three important components, described as (1) logikon, (2) tribikon or ‘practice-related’, and (3) historikon. In terms of Cratetean teaching, these three components are associated with the study of (1) diction [lexis] and ‘grammatical variations’ [grammatikoi tropoi]; (2) distinctions in styles of speaking; (3) subject-matter that is as yet unsystematized [amethodos].

§10. This formulation, derived from Crates, serves to distinguish the Library of Pergamon as a classical model, in direct comparison with the alternative classical model of the Library of Alexandria (Nagy 2024 §5). The Cratetean claim that the kritikoi of Pergamon stand for a more holistic approach to scholarship than the grammatikoi of the Library of Alexandria is connected to specific claims about Pergamene approaches to the study and even the reception of Homer. It is also connected to the rivalry between Pergamon and Alexandria over the intellectual legacy of Aristotle’s Peripatos. Relevant is this formulation by Dio of Prusa (Oration 53.1):

πολλοὶ δὲ καὶ ἄλλοι γεγράφασιν οἱ μὲν ἄντικρυς ἐγκωμιάζοντες τὸν ποιητὴν ἅμα καὶ δηλοῦντες ἔνια τῶν ὑπ’ αὐτοῦ λεγομένων, οἱ δὲ αὐτὸ τοῦτο τὴν διάνοιαν ἐξηγούμενοι, οὐ μόνον Ἀρίσταρχος καὶ Κράτης καὶ ἕτεροι πλείους τῶν ὕστερον γραμματικῶν κληθέντων, πρότερον δὲ κριτικῶν. καὶ δὴ καὶ αὐτὸς Ἀριστοτέλης, ἀφ’ οὗ φασι τὴν κριτικήν τε καὶ γραμματικὴν ἀρχὴν λαβεῖν, ἐν πολλοῖς διαλόγοις περὶ τοῦ ποιητοῦ διέξεισι, θαυμάζων αὐτὸν ὡς τὸ πολὺ καὶ τιμῶν, ἔτι δὲ Ἡρακλείδης ὁ Ποντικός.

And many others have written [about Homer], some of whom directly praise the Poet while at the same time showing some aspects of the things said by him. Still others do analysis [exēgēsis] of the meaning [dianoia] of Homer, of and by itself. Those others are not only Aristarchus and Crates and several others of those who were later called grammatikoi but who had earlier been called kritikoi. Why, even Aristotle himself—from whom they say that kritikē and grammatikē have their origin—even he in many of his dialogues is thoroughgoing about the Poet, admiring him in general and honoring him. Likewise Heraclides Ponticus.

Although the Alexandrian scholars eventually abandoned the term kritikos in favor of grammatikos, they preserved and, in fact, perfected the principles that shaped the idea of kritikos in the first place. Their work reveals most clearly the combination of selective and holistic perspectives, as we can see when we consider the role of these scholars in the formation of a canon for ancient Greek literature. It is important to keep in mind that the canon as conceived by the Alexandrians is not to be confused with the actual collection of works housed in the great library of the Museum at Alexandria. The Pinakes or ‘Tables’ of Callimachus, written into 120 scrolls, was intended not as a selection but as a complete catalogue of the holdings of the Library of Alexandria, generally organized along the lines of formal criteria, including meter (Nagy 1990, 61 n. 52, citing Zetzel 1993). On the other hand, the canon as shaped by the Alexandrian scholars was a curated selection, not the overall collection housed in the Library: “For the Alexandrian scholars, exclusion of an author from the canon [did] not preclude an active interest in that author, even as a model for imitation” (Nagy 1990, 83 n. 3).

§11. The Alexandrian classical model, as formalized in the very idea of the Pinakes of Callimachus, makes it explicit that a holistic perspective was a prerequisite for the application of the principle of selection in the curating of a canon. To this extent, then, the implication of Crates that the Alexandrian rivals lacked a holistic approach is unfair, since it implies that only the Pergamene classical model was truly holistic (Nagy 2024 §§7–8). But it may indeed be fair to say that the Pergamene classical model was more holistic than the Alexandrian, at least in the era of Crates. A striking example, to be analyzed at a later point, is the difference between Pergamene and Alexandrian approaches to Homeric poetry.

§12. Beyond the differences, however, it is important first to highlight the similarities between the Library of Pergamon as headed by Crates and the library of Alexandria as headed by his rival, Aristarchus. What follows is an epitome of a more detailed exposition published online (Nagy 2024 §§59–63). As we are about to see, the comprehensiveness of the Library at Pergamon, in general terms as well as in specifics, is based on principles that closely parallel those of the Library of Alexandria.

§13. To be sure, differences in degree exist between the two great libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon. The development of new technologies in library science involving the media of parchment in place of papyrus and the codex instead of the scroll or roll was, for example, more pronounced in Pergamon than in Alexandria (the word parchment is actually derived from “Pergamon”: see the definitive discussion of Pfeiffer 1968:236). For the moment, however, my concern is not with the physical reality of “books”—papyrus or parchment, scroll or codex—nor with questions about where and how the books were stored and the degree to which the libraries secured and preserved them. Instead, I propose to highlight the culture and learning represented by the books, which were a function of the prestige inherent in the Library as a center of learning, as a sort of Institute for Advanced Study or Wissenschaftskolleg. (See in general Baratin and Jacob 1996.)

§14. There is a strong parallelism here with the culture and learning represented by art, especially monumental art, as a visible expression of power, wealth, and prestige. Here I offer some brief introductory remarks about a dynasty known as the Attalidai, who ruled Pergamon and who were the founders of the Library there. Polybius (22.8.10) reports that King Attalus I (reign: 241–197 BCE) bought the whole island of Aegina from the Aetolians for the enormous sum of thirty talents (each talent was worth 6,000 drachmas); one of his motives seems to have been the desire to possess the archaic art. Such a move on the part of the dynasty of the Attalidai, rulers of Pergamon, is parallel to their active acquisition of books in general and to their founding of the Library of Pergamon in particular.

§15. The Attalidai of Pergamon, building on the capital investment of the hoard of Lysimachus, the uncle founder of this dynasty, have been compared to that ultimate dynasty of “princely bankers,” the Medici (Parsons 1952:22). In this context, we may view the founding of the Library of Pergamon by the dynasty of the Attalidai as closely parallel with their cultivation of the major centers of learning at Athens as represented by the three main philosophical schools there: the Academy, the Lyceum or Peripatos, and the Stoa (Pfeiffer 1968:235; Parsons 1952:22). A case in point is a story about Lacydes of Cyrene, a head of the Academy in Athens, whom King Attalus I invited to Pergamon (Parsons 1952:23). Much is made of the words Lacydes reportedly uttered in declining the invitation: ‘Pictures should be viewed from a certain distance’ (Diogenes Laertius 60.1: τὰς εἰκόνας πόρρωθεν δεῖν θεωρεῖσθαι). The next Attalid ruler, Eumenes II (reign: 197–158 BCE), invited Lycon, a Peripatetic philosopher, but he also declined; finally Crates the Stoic accepted (Pfeiffer 1968:235). As one summary puts it, “The Stoics came, and so the Stoa accepted what the Academy and Lyceum had declined.” (Parsons 1952:23; cf. Fraser 1972 II 673; also Pfeiffer 1968:235: “and then the Stoics came”).

§16. Thus it was that Crates of Mallos became the head of the so-called “Pergamene school” in the middle of the second century BCE, the same era that witnesses the apogee of the “Alexandrian school” under Aristarchus. The Library of Pergamon, sponsored primarily by Eumenes II (Strabo 13.4.2 C624), was the historical context of the scholarly activities of Crates. A conventional view of this scholar is that he was a “good Stoic,” introducing an allegorical interpretation of Homer (Parsons 1952:23). Another conventional view, inspired by Varro (De lingua latina 8.23 and 9.1), is that Crates consistently argued for the principle of Anomaly (anōmalia) in seeking to define ‘correct’ Greek, while Aristarchus stood for the opposite principle of Analogy (analogia), For background on the ancient analogy/anomaly debate, see Schenkeveld 1994:286–287 n. 13. I will return to this ancient debate over analogy/anomaly, with specific reference to the extension of this debate to Homeric criticism. For now, however, I simply note that such reductive formulations, by implying a symmetrical rivalry between Alexandria and Pergamon, tend to blur the ongoing rivalry of Pergamon with centers of learning other than Alexandria, especially Athens. In this context, we may look to Crates as the head of an important new school, parallel to and rivaling the schools of Athens in the prestige of culture and learning.

§17. The legacy of Crates as head of the Library of Pergamon can best be appreciated by reassessing the role of the Library in the reception of Homer. In what follows, I epitomize a more detailed analysis, published online (Nagy 2024 §§64–93).

§18. The Libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria each had their own distinct programs of research on Homer. They also had their own distinct texts of Homer and even their own distinct editions.

§19. Here I concentrate on the research of Crates on Homer (for an introduction: Pfeiffer 1968:239–241, also Porter 1992). My point of departure is the Vita Romana of Homer, where we read about an ‘archaic Iliad’, arkhaia Ilias, the first line of which is quoted, with an explicit reference to the editorial practice of Crates:

ἡ δὲ δοκοῦσα ἀρχαία Ἰλιάς, ἡ λεγομένη Ἀπελλικῶντος [απελικωνος ms., corr. Nauck], προοίμιον ἔχει τάδε·

Μούσας ἀείδω καὶ Ἀπόλλωνα κλυτότοξον

ὡς καὶ Νικάνωρ μέμνηται καὶ Κράτης ἐν τοῖς διωρθοτικοῖς.

But the archaic Iliad, the one that is called ‘Apellicon’s Iliad’, has this prooemium:

I sing the Muses and Apollo, famed for his bow and arrows.

This is the way Nicanor also mentions it, and so too Crates in his Diorthōtika.

Vita Romana 32.2 (ed. Wilamowitz 1929)

(See Pfeiffer 1968:239n7 for an important correction of a typographical error in the Vita Romana as edited by Wilamowitz 1929; for more on the Vita Romana: Montanari 1979:43-46 and by Broggiato 2001:140–141.)

§20. I anticipate my conclusions about the testimony as quoted here from the Vita Romana: the reference to ‘Apellicon’s Iliad’ in this context goes to show that the same Apellicon whose acquisition of select texts of Aristotle had led to the production of an “Aristoteles auctus” deserves credit for having also acquired a “Homerus auctus,” that is, a Homer text that contained extra verses not found in the texts available to, say, Aristarchus in Alexandria. (On an “Aristoteles auctus”: Nagy 2024 §§32–44, especially with reference to Strabo 13.1.54 C608–609, Plutarch Life of Sulla 26.1–2, Athenaeus 1.3a–b and 5.214d–e; extensive relevant bibliography on secondary sources commenting on these primary sources is provided by Barnes 1997; cf. also Blum 1991:52–64).

§21. Since Crates is said to have mentioned the extra verse situated at the beginning of ‘Apellicon’s Iliad’, it is generally inferred that the source of Apellicon’s acquisition was actually the Library of Pergamon.

§22. Pursuing the question of Crates’ edition of the Homeric corpus, let us take a closer look at the testimony of the Vita Romana of Homer, where the implications of a disagreement and even of a point of rivalry between the schools of Pergamon and Alexandria are visible.

§23. The Vita Romana specifies that Nicanor memnētai ‘makes mention’ of the verse in question and that Crates also makes mention of it in his Diorthōtika. (With regard to Nicanor, I infer this Alexandrian scholar, who lived in the second century CE, is referring to Crates as his source for this particular verse.) The title of this work Diorthōtika by Crates, which is cited as a source for the quotation of the verse, makes it clear that he was engaged in the diorthōsis of Homer. This term conveys the idea of establishing the ‘correct’ text of Homer. (For more on the term diorthōsisand on the related term ekdosis, see Nagy 2004:85–86, with reference to the relevant work of Montanari 1998).

§24. The Vita Romana further specifies that the quoted verse is a prooemium or ‘proem’, a term that makes sense in terms of the internal evidence of archaic Greek poetics (Nagy 1996a:62). Since we know that Crates athetized the prooemia of the Hesiodic Theogony and Works and Days (West 1966:150), we may infer that he likewise athetized this prooemium of the Iliad. By athetize (the corresponding noun is athetesis), I mean to decide that a verse is spurious by marking it as such in the margin of the definitive text (Nagy 1996a:134, 138, 146–147, 182). In this working definition of athetesis, I draw special attention to my use of the word decide, in the ancient Greek sense conveyed by the critical words krisis, enkrithentes, kritikoi. As for the Alexandrians, their Homer text seems to have omitted altogether this single-verse prooemium to the Iliad.

§25. The distinction between the Pergamene and Alexandrian editorial approaches to this single verse becomes clear when we consider the use of the word apotheton in the sense of ‘text stored away in secured places’ (Athenaeus 5.214d–e). It appears (from the passage I just cited from Athenaeus) that the ‘archaic Iliad’ mentioned by Crates is an example of such apotheta. What counts as an atheton for Crates is an apotheton as far as Aristarchus is concerned, if indeed he has no access to it. Crates athetized but included the verse in his official text of the Iliad, while Aristarchus omitted it altogether.

§26. This is no trivial matter. The fact is that the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey lack any such hymnic prooemium in the medieval manuscript tradition. The opposite situation evolved in the medieval manuscripts of the Hesiodic Theogony and Works and Days, both of which survived with and not without such hymnic prooemia: they are the first 115 and the first ten verses of the respective poems in our modern edited texts (West 1966:150 and West 1978:137). Crates athetized both these prooemia as well (Pfeiffer 1968:241; Porter 1992:98; West 1966:50, 150; West 1978:65–66, 137; see also the Life of Dionysius Periegetes, 59–60, 72 in Kassel 1985, esp. p. 72.). Aristarchus athetized the prooemium of the Hesiodic Works and Days (Pfeiffer 1968:220).

§27. There are still other instructive examples of such critical decisions. It appears that both the Alexandrians and the Pergamenes had inherited a text of the Hesiodic Theogony that included the Catalogue, and that “it was the Alexandrians, in all probability, who decided that the Theogony should end at line 1020, and the Catalogue begin there” (West 1966:50). This decision prevailed into the medieval manuscript tradition. Similarly, Apollonius of Rhodes decided that the Works and Days ended at verse 828, rejecting as spurious the verses that followed; this decision has prevailed, and in this case the rejected verses have vanished altogether (Pfeiffer 1968:220; also West 1978:64–65, 364). Similarly, Aristophanes of Byzantium decided that the Odyssey ended at verse 296 of Scroll 23; this decision, however, did not prevail (West 1966:50).

§28. Again, all these critical decisions concerning athetesis or omission are no trivial matter. Even in cases of athetesis, let alone outright omission, such decisions have occasionally led to the permanent loss of significant portions of the received text. It is important, therefore, to outline the emerging patterns of distinctions between the editorial approaches of Crates and Aristarchus:

(A) Both editors athetized verses, but both included in their texts the verses that they athetized;

(B) Aristarchus athetized more verses than Crates;

(C) Aristarchus also omitted verses that Crates included, or, to put it differently, Crates had access to texts containing some verses that Aristarchus could not or would not verify on the basis of the texts to which he had access. A conventional term used nowadays for verses omitted by Aristarchus is “plus-verses” (a most reliable treatment is Apthorp 1980; I disagree with Apthorp, however, when he infers that Homeric plus-verses are spurious or not authentic from the standpoint of oral poetics: see Nagy 1996a, 138–152);

(D) Both editors tracked variant readings within the verses, recording them and commenting on them in their formal commentaries (hupomnēmata / diorthōtika). Needless to say, the “same” verse containing different variant readings was a “different” verse as far as Aristarchus and Crates were concerned;

(E) Aristarchus used a system of signs, affixed at the left-hand margins of his text, to indicate his editorial differences with Crates and with his own Alexandrian predecessors, especially Zenodotus and Aristophanes of Byzantium (see in general McNamee 1992; also 1981). One of these signs, the diplē (shaped “>”), was used to mark verses where the athetesis of Aristarchus contradicted the non-athetesis of Crates (see Helck 1905, 50).

§29. As I already noted from the start, the editorial differences between Crates and Aristarchus can be summed up in the microcosm of an example (quoted at §5), taken from Plutarch De facie in orbe lunae 938d), where intellectuals who admire the methodology of Aristarchus as editor of Homer are blamed for neglecting the editorial work of Crates, described as ‘reading out loud’ (anagignōskein) the text of his own edition of Homer, for his followers to ‘hear’ (akouein) being read out loud from the text as transmitted by the Library of Pergamon.

§30. For Crates, as we saw in the passage from Plutarch, an additional verse in the textual transmission available to him had provided evidence for his cosmic theories about the Okeanos as a salt sea that covered the Earth, which was supposedly spherical, as opposed to the theory advanced by Aristarchus, who argued that the Homeric Okeanos was to be visualized as a fresh water river that surrounded a round and flat Earth.

§31. What was at stake, as far as Crates and Aristarchus were concerned, was, again, no trivial matter. In this case, the stakes were of cosmic dimensions. I find it ironic that I am writing this in an era when it appears fashionable to dismiss Homeric textual variations as “trivial,” “banal,” and even “boring” (to quote from Pelliccia 1997).

§32. Further ironies can be found in the fact that modern editions of Homer ignore such textual variations as those that Crates reported and interpreted. Modern scholarship may well have singled out Crates for his scientific foresight in envisioning a spherical earth instead of a circular one, had he not based his reasoning on the text of Homer. As I have already observed, modern readers find it most difficult to envision an era of intellectual history when the prestige of all higher learning centered on the study of Homer. The modern association of Crates with Homeric criticism has even diminished his potential status as a literary critic. Yet there is enough evidence from what little survives of Crates’ Homeric criticism to acclaim him as a perceptive and sensitive literary critic, one whose interpretations equal, and perhaps even surpass, those of “Longinus” On the Sublime (here I agree with Porter 1992:95–107).

§33. Also, as I noted earlier, the editorial decisions of Crates reflect a solid grounding in the textual evidence. From an empirical analysis of the formulaic composition of Iliad 14.246a, for example, I have already asserted, from the start, that there is nothing non-Homeric about this verse. From a formulaic point of view, moreover, the verse does not even necessarily convey a vision of the salt sea—let alone a spherical earth, as Crates argued. Where the verse does differ from other verses has to do with the immediate context of Okeanos. If we follow the sequence of Iliad 14.246–246a, the inherent idea is that the Okeanos generates not ‘everything’ (which would be the theme expressed by 14.246 minus14.246a), but, more specifically, all gods and men. There is nothing untraditional about this idea. In fact, it seems just as archaic in conventional outlook to picture the Okeanos as an anthropomorphic father of gods and men instead of a cosmic generator of the universe. We may compare the transformation (in Iliad 21) of the heroic theme of man-against-river into the cosmic theme of fire-against-water (Nagy 1996b:145).

§34. In taking stock of the intellectual legacy of Crates as a textual critic of Homer, it is important to revisit the distinction that Varro made in De lingua latina (8.23 and 9.1) concerning the principles of “anomaly” and “analogy” in the thinking of Crates and Aristarchus. This distinction has led to the assumption that Crates applied the principle of anomaly to admit practically any reading that suited his allegorizing theories (for such an assumption: West 1966:208). A careful reexamination of the variants attributed to Crates, as in the case of the Iliadic passage on the Okeanos, leads to a more balanced perspective (Porter 1992:85–103). Similarly, the principle of analogy as Aristarchus practiced it has led to the assumption that Aristarchus would level out anomalous variants in the name of regularity (for a survey of such assumptions: Nagy 1996a:128–129.). Yet, it is possible to show that Aristarchus was scrupulous in avoiding regularization of variants at the expense of the manuscript evidence (Ludwich 1884–1885:92, 97, 109, 114; also Nagy 1996a:129 n. 99).

§35. In the long run, it is more important to appreciate the convergences rather than the divergences between the approaches of Crates and Aristarchus to Homeric textual criticism. In fact, the intellectual histories of the Aristarchean / Alexandrian and Cratetean / Pergamene “schools” reveal their own tendencies of eventual convergence. An ideal case in point is the Stoic Panaetius, who considered himself a pupil of Crates (Strabo 14.5.16 C676), and who at the same time praised Aristarchus as a mantis ‘seer’ who knows the dianoia ‘train of thought’ of Homer (Porter 1992:70; Pfeiffer 1968:232, 245, 270; see also Fraser 1972 I 471 and IIb 682 n. 225 on the converging Alexandrian / Attalid connections of Apollodorus of Athens, originally a pupil of Aristarchus). On the other hand, the Aristarchean pupil Dionysius Thrax was strongly influenced by the Cratetean approach to “the variety of forms in the spoken language, the sunētheia” (Pfeiffer 1968:245). Crates’ preeminence in analyzing linguistic “irregularity” was generally acknowledged in the ancient world. His holistic approach to the Homeric corpus in all its potential “irregularities” can be viewed, I suggest, in the same light.

§36. Crates’ approach allows for a “Homerus auctus,” a more expansive and therefore more unwieldy corpus. But we should not assume that he made Homer be this way. Rather, I would prefer to say that the approach of his rival Aristarchus made Homer a less expansive and therefore less unwieldy corpus.

§37. To be sure, Crates, like Aristarchus, athetizes, in some instances daringly, as when he athetizes the prooemia of both the Theogony and the Works and Days of Hesiod. Athetesis does not by itself, however, make a difference in the expansiveness of the Homeric text, since both Crates and Aristarchus leave inside their received texts whatever they athetize. The difference is in the “plus-verses,” which Aristarchus leaves out but Crates leaves in. Again, we must keep in mind that Crates simply leaves things in: it is not that he puts things in. Conversely, however, we may say that Aristarchus not only leaves things out: he takes things out. I have already noted an illustration in Iliad 14.246 as Aristarchus had read it and in Iliad 14.246–46a as Crates had already read it.

§38. For an assessment of the philological acumen displayed by Crates, which I think is especially relevant to his Homeric studies, I note the reference made by Fraser (1972 II 674) to what is said by Pfeiffer (1968:239–242), who sums up this way his own “general impression” of Crates (p. 242): “Crates was a serious scholar capable of displaying solid learning who did not disregard the results of previous research, even though it was the work of scholars who were his opponents in principle.” Also to be noted, in general, is the relevant work of Wachsmuth (1860).

§39. Moving from purely philological criteria with reference to the Homeric studies of Crates at the Library of Pergamon, I now turn to the political implications of such studies as distinct from the corresponding studies of Aristarchus and his predecessors at the Library of Alexandria. What follows is an epitome of more detailed arguments available in my book Homer the Preclassic (Nagy 2010:356–362), where I summarize my even more detailed arguments as presented in the Prolegomena to Homer the Classic (Nagy 2009).

§40. We are about to see that the text of Homer as edited by Crates was “worlds apart” from the text of Homer as edited by Aristarchus. The base text used by Aristarchus is conventionally known as the Homeric Koine, which is to be contrasted with the base text used by Crates, which I have already been describing as the Homerus Auctus. As I will now argue, the edition of Homer by Aristarchus can be viewed as a political deactivation of the Homeric Koine that once represented the Athenian empire, and, conversely, the edition of Homer by Crates in the same era can be viewed as a political reactivation of the Homerus Auctus. As we will see in what follows, what I mean by political deactivation and political reactivation also corresponds respectively to an editorial deactivation and an editorial reactivation of poetry attributed to Orpheus. Orphic verses, like Homeric verses, had a political as well as poetic valence.

§41. In order to explore the political reactivation of the textual tradition described here as the Homerus Auctus, I start by highlighting Virgil’s use of this tradition in the first century BCE. As I argue in the Conclusions to Homer the Classic, Virgil made extensive use of the Homerus Auctus as edited in the second century BCE by Crates, head of the Library of Pergamon. Moreover, Virgil preferred to use the “neoteric” textual tradition of the Homerus Auctus as represented by the edition of Crates, not the “anti-neoteric” textual tradition of the Homeric Koine as represented by the edition of Aristarchus. Virgil’s epic Aeneid was based on the inclusive Homer of Crates, not on the exclusive Homer of Aristarchus.

§42. From the standpoint of a non-Alexandrian worldview as represented by Crates in Pergamon, the term neoteric in describing the textual tradition of the Homerus Auctus needs to be reconceptualized. For Crates, a verse like Iliad 14.246a was not a “plus verse,” as it must have been for Aristarchus, who rejected it as non-Homeric by excluding it from his base text. For Crates, this verse was simply Homeric, showing that Homer pictured the Okeanos as a saltwater ocean encompassing a spherical Earth, not as a freshwater river encircling a circular and flat Earth, as Aristarchus had claimed. To Crates, the Homerus Auctus must have seemed to be Homeric in its entirety.

§43. For Virgil, the Homerus Auctus as a poetic model was mediated not only by the archaizing base text of Homer as edited by Crates of Pergamon but also by that same editor’s modernizing commentaries on Homeric poetry. As Philip Hardie (1986) has demonstrated in a book about Virgil’s Aeneid, the poetics of this Roman imperial epic were decisively shaped by Crates’ modern exegesis of allegorical traditions about the world of Homer. For Virgil, as for Crates of Pergamon, the circular world of Homer was envisioned as spherical—not flat as it was for Aristarchus of Alexandria. For Virgil, this spherical world of Homer was represented by the cosmic Shield of Achilles in Iliad 18, which became the poetic model for the cosmic Shield of Aeneas as it takes shape in Aeneid 8. Virgil understood the meaning of the Homeric Shield in terms of the exegesis developed by Hellenistic allegorizers, especially by Crates. I quote from Hardie (1986:36):

[T]he circular form of that Shield was seized upon by the Hellenistic allegorizers as proof that Homer knew the universe to be spherical, and visual representations also emphasize that the circular form of the Homeric Shield is an image of the cosmos. We are made aware of the massive circular form of the Shield of Aeneas in the description of its forging [Virgil Aeneid 8.448–449]. For the Augustan reader the very shape of the Shield of Aeneas would suggest the symbolism of empire; the orbis of the Shield [as in Aeneid 8.449] becomes an emblem of the orbis terrarum. The sphere is an ambiguous symbol, for it can refer either to the spherical earth or to the spherical universe; as a symbol of power it can thus stand either for control of the oikoumenē or for a more ambitious claim to cosmic might.

§44. The Shield of Achilles, even when visualized as a sphere, must have seemed to be a purely Homeric visualization to Crates. And since this Shield of Achilles was evidently the model for the Shield of Aeneas, we may at first think that it seemed to be a purely Homeric visualization to Virgil as well. But Virgil’s poetry was referring not only to a Homeric visualization. It was referring also to a Cratetean visualization of the Homeric visualization. And the visualization of Crates, based on the Homerus Auctus as he edited it and as he commented on it, went far beyond any Homeric visualization. Virgil’s Homer was the expansive Homerus Auctus as edited and interpreted by Crates, not the narrower Homeric Koine as edited and interpreted by Aristarchus, for whom the Okeanos was a freshwater river encircling an earth that was flat, not the salty sea waters enveloping an earth that was spherical.

§45. For Crates, such allegorizing of the Homeric Shield of Achilles in Iliad XVIII involved not only cosmology but also the imperialistic ideology of the dynasty of the Attalidai in Pergamon during the second century BCE. I quote again from Hardie (1986:342):

Crates worked for the Attalid kings of Pergamum, who developed a particularly rich and extravagant imagery portraying the state and its ruler as divine agents of order, seen most notably in the Gigantomachy of the Great Altar of Zeus. Crates’ name has often been suggested in the context of the authorship of the (lost) iconographical programme of this work, which manifestly combines themes from earlier myth and poetry with contemporary political propaganda.

Although any overall design or “programme” that might have been devised by Crates for the iconography of the Great Altar of Pergamon is now lost—or never existed in the first place—we do have ample traces of this scholar’s overall design for Homeric interpretation, and we can see it attested in the fragments of his Homeric commentaries. This design is a modernizing one in its scientific reinterpretations of Homeric allegory, but it is archaizing in its reliance on a base text that represents the Homerus Auctus.

§46. For Virgil, his own allegorizing in the poetic creation of his Shield of Aeneas in Aeneid 8 matches the allegorizing of Crates himself in his commentaries on the Homeric shields of Agamemnon and Achilles in Iliad 11 and 18 respectively. In other words, the poetic model for Virgil’s Shield was the Homeric Shield as interpreted in the commentaries of Crates—and as mediated by a base text representing the Homerus Auctus, not the Homeric Koine.

§47. For Virgil, as also for Crates, such allegorizing involved not only cosmology but also the imperialistic ideology of his patrons. Just as Crates’ Homeric text and commentaries represented the Attalid dynasty of Pergamon in the second century BCE, so also Virgil’s neo-Homeric Aeneid represented the evolving Julian dynasty of Rome in the first century BCE, in the age of Augustus. Moreover, as Hardie has shown (1986:28, 123–156, 342), the cultural ideology of the Roman empire under Augustus was actually modeled on the earlier cultural ideology of the Attalidai of Pergamon. It is in this historical context that we can appreciate the poetics of Virgil’s Shield of Aeneas, where the idea of cosmos is fused with the idea of Roman imperium:

The central feature of ancient exegesis is its insistence that the great circle of the Shield of Achilles, with its abundance of scenes, is an image of the whole universe, an allegory of the cosmos. The Shield of Aeneas is also an image of the creation of a universe, but of a strictly Roman universe (though none the less comprehensive for that). There is in fact no contradiction between the universalist themes of Homer (as interpreted by antiquity) and the nationalist concerns of Virgil; the resolution is provided immediately by the Virgilian identification of cosmos and imperium, of which the Shield is the final and most vivid realization. This interpretation has the further advantage of explaining the function of the Shield within the overall structure of the poem, a problem only partially confronted by modern reassessment; as cosmic icon the Shield of Aeneas is the true climax and final encapsulation of the imperialist themes of the Aeneid (Hardie 1986:339).

From all we have seen, I conclude that the idea of cosmos and imperium in Virgil’s Aeneid was derived from the Homerus Auctus—as mediated by the Homeric edition and the Homeric commentaries of Crates in Pergamon. This Cratetean Homer was the source for the imperial design of Virgil’s Aeneid. I conclude, then, that the ideology of empire, as derived from the Homerus Auctus of Crates, was reused to represent the imperial ideology of Rome under the rule of Augustus in first century BCE. Earlier, it had been used to represent the imperial ideology of Pergamon under the rule of the Attalidai in the second century BCE.

§48. Finally, we will now see how the very idea of empire, as expressed in a tradition that I have been describing as the Homerus Auctus, promoted by Crates at the Library of Pergamon, can be traced farther back in time, far beyond the era of the Attalidai, rulers of Pergamon, all the way back the imperial ideology of Athens when it was ruled by a dynasty of tyrants known as the Peisistratidai in the sixth century BCE. What follows is epitomized from a more detailed argument in my overall essay on the libraries of Pergamon and Alexandria (Nagy 2024 §§86–107).

§49. As I will now argue, the traditional orientation of Iliad 14 246–246a, as Crates had read it, is a reflex of the imperial ideology of the Peisistratidai, rulers of Athens that sixth century BCE, that is, in the archaic and predemocratic era of that city-state. And, as I will also argue, this imperial ideology was conveyed by way of an epic tradition that can best be described as not only Homeric but also Orphic, reflecting the poetic and hermeneutic traditions that the ancient world ascribed to Orpheus. In terms of my argument, such passages as we see in Iliad 14 246–246a are typical of an augmented Homer, a Homerus Auctus, where the Homeric tradition is augmented primarily by Orphic traditions. To be contrasted is the editorial mindset of Aristarchus at the Library of Alexandria, for whom a verse like 246a in Iliad 14 would be merely a “plus-verses” emanating from Homer editions that had been contaminated, as it were, by Orphic traditions. As far as the Pergamene scholars were concerned, however, such Orphic accretions in the Homeric textual tradition were not “contaminations” at all, since Orpheus (as well as Musaeus) supposedly lived before Homer (documentation in Nagy 1990:216n10). Pergamene editorial practice apparently included “Orphic” plus-verses in the Homeric text, as contrasted with the Alexandrian practice of excluding them—that is, omitting them altogether from the text, instead of merely athetizing them. Such conflicting editorial practices seem reflected in the following piece of ancient witticism by way of Seneca Epistle 88.39:

annales evolvam omnium gentium et quis primus carmina scripserit quaeram? Quantum temporis inter Orphea intersit et Homerum, cum fastos non habeam, computabo? Et Aristarchi ineptias, quibus aliena carmina conpunxit, recognoscam et aetatem in syllabis conteram?

Shall I unroll the annals of the world’s history and try to find out who first wrote poetry? Shall I make an estimate of the number of years that separate Orpheus and Homer, although I do not have the records [fasti]? And shall I investigate the absurd writings of Aristarchus, wherein he ‘skewered’ [conpunxit] other men’s verses, and wear my life away on syllables?

The ‘skewering’ refers to the Alexandrian procedure of marking with an obelos ‘skewer’ those verses that are to be athetized (Pfeiffer 1968:115, 178). The mention of syllables may refer to the proverbial Aristarchean obsession with the minutiae of monosyllabic words, an obsession that some followers of Crates ridiculed (documentation in Nagy 2024 §87). Most important of all, the theme of an absence of written recordings (fasti) of Orpheus and Homer reflects what appears to be an ongoing dispute between the followers of Crates and Aristarchus concerning the provenience of Homer.

§50. It is easier to start with Aristarchus: he believed, it appears, that Homer was an Athenian who lived around 1000 BCE (Scholia A for Iliad 13.197), and that he wrote down the Iliad and Odyssey (Scholia A to Iliad 17.719). There is no indication, by contrast, that Crates deemed Homer to be an Athenian, let alone a writer of his own poems. Crates seems not to have thought of Homer as an Athenian (Helck 1905:63 and 74–75), though he may have thought that Homer used sporadic Atticisms (Wachsmuth 1860:39). Again, I see a reactive Aristarchus: he wants to posit an Athenian Homer by extrapolating beyond what Crates was willing to extrapolate. By contrast, Crates seems to have followed a mythologized explanation—an aetiology—that commonly known today as the Peisistratean Recension. In terms of such an aetiology, there were major lacunae in the written tradition of Homer until the Peisistratidai reassembled the corpus, as it were, of his poetry.

§51. The idea of a Peisistratean Recension, according to one expert, was “unknown in the heyday of Alexandrian scholarship” (Janko 1992:32). I would rather say “deliberately ignored” or at least underrepresented, not “unknown.” There is a parallel pattern in the underrepresentation of Crates. As Pfeiffer points out, the main surviving source for Crates is not the body of scholia of ms A of the Iliad (Venetus 454), which is our main source for Aristarchus, but the so-called exegetical scholia of ms B (Venetus 453), of ms T (Townley = British Museum Burnley 86), and the Genavensis, as well as the related scholia in P.Oxy. 221 and the scholia in mss HM of the Odyssey; “and particularly Eustathius, who was able to excerpt scholia lost to us” (Pfeiffer 1968:239–240). So also with the idea of a Peisistratean Recension: the absence of references to this idea in the Iliadic A scholia, reflecting primarily the Aristarchean tradition, is remarkable. In the Homeric scholia, mentions of the Peisistratean Recension surface very rarely: only in scholia T at Iliad 10.1 and the scholia H at Odyssey 11.604.

§52. Scholia H to verse 604 of Odyssey 11 report that this Homeric passage (11.602–604) was the creation of one Onomacritus. According to Tzetzes (On Comedy 20 ed. Kaibel), Onomacritus was one of the four redactors responsible for the Peisistratean Recension. Elsewhere, as in Pausanias 9.35.5, Onomacritus is a cover-name for the author of Orphic poems. In general, the ultimate form of the Orphic poems “is unmistakably connected with the Pergamene account of the Pisistratean recension of the Homeric poems” (West 1983:249).

§53. Various scholars have argued that the “inventor” of the aetiological narrative about a Peisistratean Recension was a Pergamene scholar, Asclepiades of Myrlea (dated around 100 BCE), whose purpose was to provide a counterweight to the Alexandrian theories of Homer’s provenience (Davison 1955, esp. 21; also Janko 1992:32). By contrast, I have counterargued for a much earlier dating of this aetiology, which I think is roughly contemporaneous with the era of the Peisistratidai themselves (Nagy 1996b:95–96). In support of this counterargument, we may note that Onomacritus is mentioned already by Herodotus (7.6.3) as a collaborator of the Peisistratidai, serving as a diathetēs ‘arranger’ of oracular poetry for their political purposes. In this context, moreover, Herodotus accuses Onomacritus of fraudulently making additions to the oracular poetry of Musaeus (commentary on the narrative of Herodotus: Nagy 1996b:73; also Nagy 1990:174). Such additions, of course, would have been athetized by the Pergamene scholars, although the athetized lines could have remained in the text.

§54. Here I return to the fact that Aristarchus in his own publications carried on an extended debate with Crates concerning the textual criticism of Homer, and I cross-refer here to my comments above about the practice, adopted by Aristarchus, of placing the sign known as the diplē on the left side of lines where he disputed the authenticity of Homeric verses accepted by rival editors like Crates. In view of this Aristarchean practice, it seems to me more likely that it was the Aristarchean idea of an Athenian Homer, who was supposedly writing his poems around 1000 BCE, that provided a counterweight to the idea of a Peisistratean Recension as accepted by Crates and the Pergamenes. Asclepiades of Myrlea is simply one of the more visible later representatives of this earlier idea.

§55. If indeed Aristarchus’ idea of an Athenian Homer is an innovation meant to counter the older idea of the Peisistratean Recension, as Crates and the Pergamenes accepted, we can better understand the reasoning of Josephus (first century CE) when he says that the songs of Homer were not written down but remembered over time, then scattered, and finally reassembled:

ὅλως δὲ παρὰ τοῖς Ἕλλησιν οὐδὲν ὁμολογούμενον εὑρίσκεται γράμμα τῆς Ὁμήρου ποιήσεως πρεσβύτερον, οὗτος δὲ καὶ τῶν Τρωϊκῶν ὕστερος φαίνεται γενόμενος, καί φασιν οὐδὲ τοῦτον ἐν γράμμασι τὴν αὑτοῦ ποίησιν καταλιπεῖν, ἀλλὰ διαμνημονευομένην ἐκ τῶν ᾀσμάτων ὕστερον συντεθῆναι καὶ διὰ τοῦτο πολλὰς ἐν αὐτῇ σχεῖν τὰς διαφωνίας·

In general, no commonly recognized writing is found among the Greeks older than the poetry of Homer. But he too seems to have been later than the Trojan War, and they say that not even he left his poetry in writing, but it was preserved by memory [diamnēmoneuomenēn] and assembled [suntethēnai] later from the songs. And it is because of this that there are so many inconsistencies [diaphōniai] in it.

Josephus Contra Apionem 1.12–13

Evidently, Josephus was using the older construct of the Peisistratean Recension in order to undercut the ideology of his Aristarchean opponent, Apion (Nagy 2004:4, 9–12).

§56. Much has been made of the “vanishing” and then the subsequent reappearance of a corpus of Aristotle’s esoterica (Canfora 1990; extensive bibliography in Nagy 2024 §§33–44). But we must also reckon with the “vanishing” of Aristotle’s ekdosis of Homer. Mentioned in the Vita Marciana, this ekdosis fails to resurface in the form of a continuing textual tradition that claims Aristotle as editor.

§57. Here it may be useful to reconsider the standpoint of the brief report in the Vita Marciana: in the context of a listing of Aristotle’s own works, the mention of an ekdosis of Homer implies merely the existence of an edition produced by the Lyceum as a library, not necessarily a work authored by Aristotle as an individual. Here I turn to the evidence for a massive transfer of both learning and texts from Lyceum to Museum in the era of Demetrius of Phaleron, who was closely associated with both the Lyceum and the Museum.

§58. In my overall essay on ancient Greek libraries (Nagy 2024), I defended in some detail (especially at §§14–19 there) the validity of surviving ancient reports about editorial work on Homeric textual transmission in the Peripatetic tradition of the Lyceum founded by Aristotle. In the same essay, though I defended the validity of such reports, I also took note of the fact that the importance of an ekdosis of Homer, attributed to Aristotle himself, eventually gave way to the importance of later editorial work on Homer that was ongoing at the Libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon (Nagy 2024 §§100–105).If the editorial work of the Peripatetics on Homer was not of much use any more for Alexandrians like Aristarchus, it was of even less use to Pergamenes like Crates, whose holistic approach to the text of Homer seems to have embraced even Orpheus and Musaeus.

§59. In two ways, however, the scholars of the Library of Pergamon lived up to the ideals of Aristotle in their analysis of classical texts, even if not in their editing of Homer. First, they were systematic, as Suetonius reports explicitly (De Grammaticis et Rhetoribus 2). Second, they were comprehensive, to the point that their cataloguing system surpassed the Library of Alexandria in the popular imagination. Witness the following remark of Athenaeus 8.336d, on an obscure comedy of Alexis: ‘Certainly neither Callimachus nor Aristophanes has catalogued it, nor have even those who compiled the catalogues in Pergamon’.

§60. I end where I began, with a description, by Dio of Prusa (Oration 53.1), of the scholars of both Alexandria and Pergamon:

And many others have written [about Homer], some of whom directly praise the Poet while at the same time showing some aspects of the things said by him. Still others do analysis [exēgēsis] of the meaning [dianoia] of Homer, of and by itself. Those others are not only Aristarchus and Crates and several others of those who were later called grammatikoi but who had earlier been called kritikoi. Why, even Aristotle himself—from whom they say that kritikē and grammatikē have their origin—even he in many of his dialogues is thoroughgoing about the Poet, admiring him in general and honoring him.

Bibliography

Allen. Reginald E. 1983. The Attalid Kingdom: A Constitutional History. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Apthorp, Michael J. 1980. The Manuscript Evidence for Interpolation in Homer. Heidelberg: Winter.

Apthorp, Michael J. 1995. Review of J. R. Tebben 1994. Classical Review 45:221–222.

Baratin, Marc, and Christian Jacob. 1996. Le pouvoir des bibliothèques: La Mémoire des livres en Occident. Paris: Albin Michel.

Barnes, Jonathan. 1997. “Roman Aristotle.” In Philosophia Togata II: Plato and Aristotle at Rome, ed. Jonathan Barnes and Miriam Griffin, 1–69. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Blum, Rudolf. 1991. Kallimachos: The Alexandrian Library and the Origins of Bibliography. Madison, WI.

Broggiato, Maria, ed.. 2001, Cratete di Mallo: I frammenti. Edizione, Introduzione e Note. Pleiadi: Studi sulla letteratura antica (ed. Franco Montanari), 2. La Spezia: Agorà Edizioni.

Canfora, Luciano. 1990. The Vanished Library: A Wonder of the Ancient World. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Translated by Martin Rylefrom (1987) from La biblioteca scomparsa. Palermo: Sellerio Editore.

Davison, J.A. 1955. “Peisistratus and Homer.” Transactions of the American Philological Association 86:1–21.

Fraser, Peter M. 1972. Ptolemaic Alexandria. I–III. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hansen, Esther V. 1971. The Attalids of Pergamon. 2nd ed. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Hardie, Philip. 1985. “Imago Mundi: Cosmological and Ideological Aspects of the Shield of Achilles.” Journal of Hellenic Studies 105:11–31.

Hardie, Philip. 1986. Virgil’s Aeneid: Cosmos and Imperium. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Helck, Ioannes, 1905. De Cratetis Mallotae studiis criticis quae ad Iliadem spectant. Leipzig.

Jacob, Christian. 1996. “Lire pour écrire: navigations alexandrines.” In Baratin and Jacob 1996, 47–83.

Janko, Richard, ed. 1992. The Iliad: A Commentary. Vol. 4, Books 13–16. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kassel, Rufolf. 1973. “Antimachos in der Vita Chisiana des Dionysios Periegetes.” In Catalepton: Festschrift für Bernhard Wyss zum 80. Geburtstag, ed. Christoph Schäublin, 69–76. Basel.

Keaney, John J., and Robert Lamberton, eds. 1996. [Plutarch] Essay on the Life and Poetry of Homer. APA American Classical Studies 20. Atlanta.

Ludwich, Arthur. 1884–1885. Aristarchs Homerische Textkritik nach den Fragmenten des Didymos. 2 vols. Leipzig: Teubner.

McNamee, Kathleen. 1981. “Aristarchus and Everyman’s Homer.” Greek, Roman and Byzantine Studies 22:247–255.

McNamee, Kathleen. 1992. Sigla and Select Marginalia in Greek Literary Papyri. Brussels: Fondation Égyptologique Reine Élisabeth.

Montanari, Franco. 1979. Studi di filologia omerica antica, I. Pisa: Giardini.

Montanari, Franco. 1998. “Zenodotus, Aristarchus and the Ekdosis of Homer.” In Most 1998:1–21.

Montanari, Franco, ed. 1994. La philologie grecque à l’époque hellénistique et romaine. Entretiens sur l’antiquité classique 40, Fondation Hardt. Geneva.

Most, Glenn W., ed. 1998. Editing Texts = Texte edieren. Aporemata 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Nagy, Gregory.1990. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Pindars_Homer.1990.

Nagy, Gregory. 1996a. Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Poetry_as_Performance.1996.

Nagy Gregory. 1996b. Homeric Questions. Austin: University of Texas Press. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homeric_Questions.1996.

Nagy, Gregory. 1998a. “The Library of Pergamon as a Classical Model.” In Pergamon: Citadel of the Gods, ed. Helmut Koester, 185–232. Harvard Theological Studies 46.

Nagy, Gregory. 2004. Homer’s Text and Language. Chicago and Urbana: University of Illinois Press. https://chs.harvard.edu/book/nagy-gregory-homers-text-and-language/.

Nagy, Gregory. 2007. Review of Broggiato 2001. The Classical World 100, No. 4, 468–469.

Nagy, Gregory. 2009. Homer the Classic. Hellenic Studies 36. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC: Harvard University Press. Online edition 2008. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Classic.2008.

Nagy, Gregory. 2010. Homer the Preclassic. Sather Classical Lectures 67, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. Online edition 2009. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Preclassic.2009.

Nagy, Gregory, 2024. “The Libraries of Alexandria and Pergamon as Classical Models.” Classical Continuum. Accessed November 20, 2024. https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/the-libraries-of-alexandria-and-pergamon-as-classical-models/.

Nesselrath, Heinz-Günther, ed. 1991. Rudolf Kassel: Kleine Schriften. Berlin / New York.

Parsons. Edward A. 1952. The Alexandrian Library, Glory of the Hellenic World: Its Rise, Antiquities, and Destructions. New York: Elsevier.

Pelliccia, Hayden N. 1997.11.20. “As Many Homers As You Please.” New York Review of Books 44.18:44–48.

Pfeiffer, Rudolf. 1968. History of Classical Scholarship from the Beginnings to the End of the Hellenistic Age. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Porter, James I. 1992. “Hermeneutic Lines and Circles: Aristarchus and Crates on the Exegesis Of Homer.” In Homer’s Ancient Readers: The Hermeneutics Of Greek Epic’s Earliest Exegetes, ed. Robert Lamberton and John J. Keaney, 67–114. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Rengakos, Antonios. 1993. Der Homertext und die Hellenistischen Dichter. Hermes Einzelschriften 64. Stuttgart.

Richardson, Nicholas J. 1994. “Aristotle and Hellenistic Scholarship.” In Montanari 1994:7–28.

Schenkeveld, Dirk M. 1994. “Scholarship and Grammar.” In Montanari 1994:263–298.

Schultz, Alexandra. 2021. Imagined Histories: Hellenistic Libraries and the Idea of Greece. PhD dissertation, Harvard University.

Schultz, Alexandra. 2023. “Origin Stories: Plundered Libraries and Theories of Appropriation in Greek and Roman Imperial Literature.: Transactions of the American Philological Association 153:389–430.

Schultz, Alexandra. Forthcoming. “Collection.” In Writing, Enslavement, and Power in the Roman Mediterranean, 100 BCE–300 CE, ed. Candida Moss, Jeremiah Coogan, and Joseph Howley. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Tebben, J. R. 1994. Concordantia Homerica, Pars I: Odyssea. A Complete Concordance to the Van Thiel Edition of Homer’s Odyssey. 2 vols. Hildesheim: Georg Olms AG.

Wachsmuth, Curt. 1860. De Cratete Mallota. Leipzig: Teubner.

West, Martin L. 1966. ed., with commentary. Hesiod: Theogony. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

West, Martin L. 1978. ed., with commentary. Hesiod: Works and Days. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

West, Martin L. 1983. The Orphic Poems. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Ulrich von. 1929. Vitae Homeri et Hesiodi. 2nd ed. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter.

Zetzel, James E. G. 1983. “Re-creating the Canon: Augustan Poetry and the Alexandrian Past.” Critical Inquiry 10:83–105. Also 1984, in Canons, ed. Robert von Hallberg, 107–129. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.