A retranslation based on an original translation by W.H.S. Jones, 1918 (Scroll 2 with H.A. Ormerod), containing some of the footnotes added by Jones.

This retranslation is by Gregory Nagy | 2022.01.28*

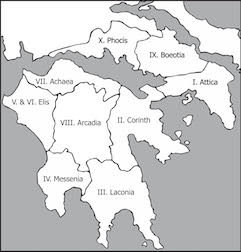

Scroll I. Attica

{1.12.5} Pyrrhos was brought over to Sicily by an embassy of the Syracusans. The Carthaginians had crossed over and were destroying the Greek [Hellēnides] cities, and had set up a siege of Syracuse, the only city now remaining. When Pyrrhos heard this from the envoys he abandoned Tarentum and the Italiots on the coast, and crossing into Sicily forced the Carthaginians to raise the siege of Syracuse. In his self-conceit, although the Carthaginians, being Phoenicians of Tyre by ancient descent, were more experienced seafarers than any other barbarian people of that day, Pyrrhos was nevertheless encouraged to engage them in a naval battle, employing the people of Epeiros, the majority of whom, even after the capture of Troy, knew nothing of the sea nor even as yet how to use salt. Witness the words of Homer in the Odyssey:

{1.13.2} After the defeat in Italy, Pyrrhos gave his forces a rest and then declared war on Antigonos, his chief ground of complaint being the failure to send reinforcements to Italy. Overpowering the native troops of Antigonos and his Gallic mercenaries he pursued them to the coast cities, and himself reduced upper Macedonia and the Thessalians. The extent of the fighting and the decisive character of the victory of Pyrrhos are shown best by the Celtic armor dedicated in the sanctuary of Itonian Athena between Pherai and Larisa, with this inscription on them:

{1.13.3} hang up, Pyrrhos did, taking them from the bold Gauls [Galatai],

having destroyed the entire army of Antigonos. No big wonder [thauma],

since the Aiakidai are masters of the spear, even now as also in the past.

These shields then are here, but the shields of the Macedonians themselves he dedicated to Dodonian Zeus. They too have an inscription:

and they brought slavery upon the Greeks [Hellēnes].

Now ownerless they lie by the columns of the temple [nāos] of Zeus,

spoils from boastful Macedonia.

{1.37.2} A little way past the tomb of Themistocles is a precinct [temenos] that is sacred [hieron] to Lakios, a hero [hērōs], and there is a deme [dēmos] called after him, Lakiadai; also the tomb [mnēma] of Nikokles of Tarentum, who won a unique reputation as a citharode [kitharōidos = kitharā-singer]. There is also an altar [bōmos] of Zephyrus and a sanctuary [hieron] of Demeter and her daughter. With them Athena and Poseidon have honors [tīmai]. They say that in this place [khōrion] Phytalos welcomed Demeter in his home, for which act the goddess [theos (feminine)] gave him the fig tree. This story is borne out by the inscription on the tomb of Phytalos:

Demeter, when she first created revealed [phainein] the fruit-of-the-harvest [karpos] that comes in the season of harvesting.

It is the sacred [hierē] fig-tree [sukē], that is what the generation of mortals [thnētoi] have have given it as a name. [140]

Whence Phytalos and his lineage have received honors immortal.

Scroll II. Corinth

{2.3.4} Proceeding on the direct road to Lekhaion we see a bronze statue [agalma] of a seated Hermes. By him stands a ram, for Hermes is the god who is thought most to care for and to increase flocks, as Homer puts it in the Iliad:

Rich in flocks, for the god vouchsafed him wealth in abundance.

The story told at the mysteries of the Mother about Hermes and the ram I know but do not relate. After the image of Hermes come Poseidon, Leukothea, and Palaimon on a dolphin.

{2.6.4} On this matter Asios the son of Amphiptolemos [157] says in his poem:

Daughter of Asopos, the swift, deep-eddying river,

Having conceived of Zeus and Epopeus, shepherd of peoples. [158]

Homer traces their descent to the more august side of their family, and says that they were the first founders of Thebes, in my opinion distinguishing the lower city from the Kadmeia.

{2.7.1} From that time the Sikyonians became Dorians and their land a part of the Argive territory. The city built by Aigialeus on the plain was destroyed by Demetrios the son of Antigonos, [159] who founded the modern city near what was once the ancient citadel. The reason why the Sikyonians grew weak it would be wrong to seek; we must be content with Homer’s saying about Zeus:

When they had lost their power there came upon them an earthquake, which almost depopulated their city and took from them many of their famous sights. It damaged also the cities of Caria and Lycia, and the island of Rhodes was very violently shaken, so that it was thought that the Sibyl had had her utterance about Rhodes [160] fulfilled.

{2.12.6} The Argives say that Phlias, who has given the land its third name, was the son of Ceisus, the son of Temenus. This account I can by no means accept, but I know that he is called a son of Dionysus, and that he is said to have been one of those who sailed on the Argo. The verses of the Rhodian poet confirm me in my opinion:

{2.14.3} But it is possible that Dysaules came to Phleious for some other reason than that given by the Phliasians. I do not believe either that he was related to Keleus, or that he was in any way distinguished at Eleusis, otherwise Homer would never have passed him by in his poems. For Homer is one of those who have written in honor of Demeter, and when he is making a list of those to whom the goddess taught the mysteries he knows nothing of an Eleusinian named Dysaules. These are the verses:

Also to mighty Eumolpos, to Keleus, leader of peoples,

Cult of the holy rites, to them all her mystery telling.

{2.20.10} This fight had been foretold by the Pythian priestess in the oracle quoted by Herodotus, who perhaps understood to what it referred and perhaps did not:

Driving away the male, and wins great glory in Argos,

Many an Argive woman will tear both cheeks in her sorrow.

Such are the words of the oracle referring to the exploit of the women.

{2.24.4} The reason for its three eyes one might infer to be this. That Zeus is king in the sky [ouranos] is a saying common to all men. As for him who is said to rule under the earth, there is a verse of Homer which calls him, too, Zeus:

The god in the sea, also, is called Zeus by Aeschylus, the son of Euphorion. So whoever made the image made it with three eyes, as signifying that this same god rules in all the three ‘allotments’ of the Universe, as they are called.

{2.33.2} Kalaureia, they say, was sacred to Apollo of old, at the time when Delphi was sacred to Poseidon. It is also said that the two gods exchanged the two places. They still say this, and quote an oracle:

Pythō, too, the holy, and Taenarum swept by the high winds.

At any rate, there is a holy sanctuary of Poseidon here, and it is served by a maiden priestess until she reaches an age fit for marriage.

Scroll III. Laconia

{3.2.4} and the next kings of this house, Doryssus, son of Labotas, and Agesilaos, son of Doryssus, were soon both killed. Lycurgus (Lykourgos) too laid down their laws for the Lacedaemonians in the reign of Artesilaos; some say that he was taught how to do this by the Pythian priestess, others that he introduced Cretan institutions. The Cretans say that these laws of theirs were laid down by Minos, and that Minos was not without divine aid in his deliberations concerning them. Homer too, I think, refers in riddling words to the legislation of Minos in the following verses:

Ruled as king, and enjoyed familiar converse with great Zeus.

{3.8.9} Yet further fuel for the controversy between Agesilaos and Leotykhides was supplied by the oracle that was delivered at Delphi to this effect:

Never let thy sound limbs give birth to a kingdom that lame is.

Too long then shalt thou lie in the clutches of desperate hardships;

Turmoil of war shall arise, o’erwhelming men in its billows.”

{3.19.8} They surname him Theritas after Thero, who is said to have been the nurse of Ares. Perhaps it was from the people of Kolkhis that they heard the name Theritas, since the Greeks know of no Thero, nurse of Ares. My own belief is that the surname Theritas [261] was not given to Ares because of his nurse, but because when a man meets an enemy in battle he must cast aside all gentleness, as Homer says of Achilles:

{3.20.6} I know also of the following rite which is performed here. By the sea was a city Helos, which Homer too has mentioned in his list of the Lacedaemonians:

It was founded by Helios [Hĕlios not Hēlios], the youngest of the sons of Perseus, and the Dorians afterwards reduced it by siege. Its inhabitants became the first slaves of the Lacedaemonian state, and were the first to be called Helots [heilōtes], as in fact heilōtesthey were. The slaves afterwards acquired, although they were Dorians of Messenia, also came to be called Helots, just as the entire lineage of people who were called Hellēnes [‘Greeks’] were named after the region in Thessaly once called Hellas.

{3.21.9} Him whom the people of Cythium name Old Man, saying that he lives in the sea, I found to be Nereus. They got this name originally from Homer, who says in a part of the Iliad, where Thetis is speaking:

Plunge, to behold the old man of the sea and the home of your father.

Here is also a gate called the Gate of Castor (Kastor), and on the citadel have been built a temple and image of Athena.

{3.25.2} but according to another account Pyrrhikos was one of the gods called Kouretes. Others say that Silenus came from Malea and settled here. That Silenus was brought up in Malea is clear from these words in an ode of Pindar:

Not that Pindar said his name was Pyrrhikos; that is a statement of the men of Malea.

Scroll IV. Messenia

{4.1.3} Before the battle which the Thebans fought with the Lacedaemonians at Leuktra, and the foundation of the present city of Messene under Ithome, I think that no city had the name Messene. I base this conclusion principally on Homer’s lines. [277] In the catalogue of those who came to Troy he enumerated Pylos, Arene and other towns, but called no town Messene. In the Odyssey he shows that the Messenians were a tribe and not a city by the following:

{4.1.4} He is still more clear when speaking about the bow of Iphitos:

in the dwelling of Ortilokhos.”

By the dwelling of Ortilokhos he meant the city of Pherai in Messene, and explained this himself in the visit of Peisistratos to Menelaos:

son of Ortilokhos.”

{4.1.6} But the mysteries of the Great Goddesses were raised to greater honor many years later than Kaukon by Lykos, the son of Pandion, an oak-wood, where he purified the celebrants, being still called the wood of Lykos. That there is a wood in this land so called is stated by Rhianus the Cretan:

{4.6.5} It was this Theopompos who put an end to the war, and my evidence is the lines of Tyrtaeus, which say:

Aristomenes then in my view belongs to the time of the second war, and I will relate his history when I come to this.

{4.9.2} A small town existed here, which they say Homer mentions in the Catalogue:

To this town they withdrew, extending the old circuit to form a sufficient protection for them all. The place was strong in other respects, for Ithome falls short of none of the mountains within the Isthmus in height and at this point was most difficult to climb.

{4.9.4} Tisis, reaching Ithome with all speed, delivered the oracle to the king, and soon afterwards died of his wounds. Euphaes assembled the Messenians and made known the oracle:

{4.12.1} The Lacedaemonians were distressed by the reverse that had befallen them. Their losses in the battle were great and included important men, and they were inclined to despair of all hope in the war. For this reason they sent envoys to Delphi, who received the following reply from the Pythia:

{4.12.3} Failing in their attempt, the Lacedaemonians next attempted to break up the Messenian alliance. But when repulsed by the Arcadians, to whom their ambassadors came first, they put off going to Argos. Aristodemos, hearing of the Lacedaemonian intrigues, also sent men to enquire of the god. And the Pythia replied to them:

At the time Aristodemos and the seers were at a loss to interpret the saying, but in a few years the god was like to reveal it and bring it to fulfillment.

{4.12.7} After this, as the twentieth year of the war was approaching, they resolved to send again to Delphi to ask concerning victory. The Pythia made answer to their question:

{4.13.6} Even then the Messenians were not inferior in courage and brave deeds, but all their generals were killed and their most notable men. After this they held out for some five months, but as the year was coming to an end deserted Ithome, the war having lasted twenty years in all, as is stated in the poems of Tyrtaeus:

{4.14.5} As to the wanton punishments which they inflicted on the Messenians, this is what is said in Tyrtaeus’ poems:

That they were compelled to share their mourning, he shows by the following:

{4.15.2} Tyrtaeus has not recorded the names of the kings then reigning in Lacedaemon, but Rhianos stated in his epic that Leotykhides was king at the time of this war. I cannot agree with him at all on this point. Though Tyrtaeus makes no statement, he may be regarded as having done so by the following; there are lines of his which refer to the first war:

{4.15.5} It was the view of Aristomenes that any man would be ready to die in battle if he had first done deeds worthy of record, but that it was his own especial task at the very beginning of the war to prove that he had struck terror into the Lacedaemonians and that he would be more terrible to them for the future. With this purpose he came by night to Lacedaemon and fixed on the temple of Athena of the Brazen House a shield inscribed

{4.16.6} The Lacedaemonians were thrown into despair after this blow and purposed to put an end to the war. But Tyrtaeus by reciting his poems contrived to dissuade them, and filled their ranks from the Helots to replace the slain. When Aristomenes returned to Andania, the women threw ribbons and flower blossoms over him, singing also a song which is sung to this day:

{4.17.11} The length of the siege is proved by these lines of the poet Rhianus, regarding the Lacedaemonians:

He reckons winters and summers, by ‘green herbs’ meaning the green wheat or the time just before harvest.

{4.20.1} But in the eleventh year of the siege it was fated that Eira should be taken and the Messenians dispersed, and the god fulfilled for them an oracle given to Aristomenes and Theoklos. They had come to Delphi after the disaster at the Trench and asked concerning safety, receiving this reply from the Pythia:

{4.22.7} When this was declared to all, the Arcadians themselves stoned Aristocrates [Aristokrates] and urged the Messenians to join them. They looked to Aristomenes. But he was weeping, with his eyes fixed on the ground. So the Arcadians stoned Aristocrates [Aristokrates] to death and flung him beyond their borders without burial, and set up a tablet in the precinct of Zeus Lykaios with the words:

Hard it is for a man forsworn to hide from God.

Hail, king Zeus, and keep Arcadia safe.”

{4.27.4} Epameinondas was most strongly drawn to the foundation by the oracles of Bacis, who was inspired by the Nymphs and left prophecies regarding others of the Greeks as well as the return of the Messenians:

I have discovered that Bacis also told in what manner Eira would be captured, and this too is one of his oracles:

{4.30.4} Homer is the first whom I know to have mentioned Fortune in his poems. He did so in the Hymn to Demeter, where he enumerates the daughters of Okeanos, telling how they played with Kore the daughter of Demeter, and making Fortune one of them. The lines are:

{4.32.5} What I myself heard in Thebes gives probability to the Messenian account, although it does not coincide in all respects. The Thebans say that when the battle of Leuktra was imminent, they sent to other oracles and to enquire of the god of Lebadeia. The replies of the Ismenian and Ptoan Apollo are recorded, also the responses given at Abaiand at Delphi. Trophonios, they say, answered in hexameters:

{4.33.2} The statue of Zeus is the work of Ageladas [311] and was made originally for the Messenian settlers in Naupaktos. The priest is chosen annually and keeps the image in his house. [312] They keep an annual festival, the Ithomaia, and originally a musical contest was held. This can be gathered from the epic lines of Eumēlos and other sources. Eumēlos, in his processional hymn to Delos, says:

I think that he wrote the lines because he knew that they held a musical contest.

Scroll V. Elis, Part 1

{5.2.5} For Timon, a man of Elis, won victories in the pentathlon at the Greek Games, and at Olympia, there is even a statue of him, with an elegiac inscription giving the garlands he won and also the reason why he secured no Isthmian victory. The inscription sets forth the reason thus:

About the baleful death of the Molionidai.

{5.3.1} Enough of my discussion of this question. Hēraklēs afterwards took Elis and sacked it, with an army he had raised of Argives, Thebans and Arcadians. The Eleians were aided by the men of Pisa and of Pylos in Elis. The men of Pylos were punished by Hēraklēs, but his expedition against Pisa was stopped by an oracle from Delphi that goes like this:

This oracle proved the salvation of Pisa. To Phyleus Hēraklēs gave up the land of Elis and all the rest, more out of respect for Phyleus than because he wanted to do so: he allowed him to keep the prisoners, and Augeias to escape punishment.

{5.6.2} As to the ruins of Arene, no Messenian and no Eleian could point them out to me with certainty. Those who care to do so may make all sorts of different guesses about it, but the most plausible account seemed to me that of those who held that in the heroic age and even earlier, Samikon was called Arene. These quoted too the words of the Iliad:

{5.7.3} This account of Alpheios to Ortygia. But that the Alpheios passes through the sea and mingles his waters with the spring at this place, I cannot disbelieve as I know that the god at Delphi confirms the story. For when he dispatched Arkhias the Corinthian to found Syracuse, he uttered this oracle:

Over against Trinakria, where the mouth of Alpheios bubbles

Mingling with the springs of broad Arethousa.

For this reason, therefore, because the water of the Alpheios mingles with the Arethousa, I am convinced that the story arose of the river’s love-affair.

{5.10.4} At Olympia, a gilded caldron stands on each end of the roof, and a Nike, also gilded, is set in about the middle of the pediment. Under the image of Nike has been dedicated a golden shield with Medusa the Gorgon in relief. The inscription on the shield declares who dedicated it and the reason why they did so. It runs thus:

The Lacedaemonians and their allies dedicated it,

A gift taken from the Argives, Athenians, and Ionians,

The tithe offered for victory in war.

This battle I also mentioned in my write-up [sun-graphē] of Attica. Then I described the tombs that are in Athens.

{5.18.2} A beautiful woman is punishing an ugly one, choking her with one hand and with the other striking her with a staff. It is Justice who thus treats Injustice. Two other women are pounding in mortars with pestles; they are supposed to be wise in the lore of medicine, though there is no inscription to them. Who the man is who is followed by a woman is made plain by the hexameter verses, which run thus:

{5.18.4} There are also figures of Muses singing, with Apollo leading the song; these too have an inscription: This is Leto’s son, Prince Apollo, far-shooting; Around him are the Muses, a graceful choir, whom he is leading. Atlas too is supporting, just as the story has it, sky [ouranos] and earth upon his shoulders; he is also carrying the apples of the Hesperides. A man holding a sword is coming towards Atlas. This everybody can see is Hēraklēs, though he is not mentioned specially in the inscription, which reads:

{5.19.3} Aithra, the daughter of Pittheus, lies thrown to the ground under the feet at Helen. She is clothed in black, and the inscription upon the group is an hexameter line with the addition of a single word:

From Athens.

{5.19.4} Such is the way this line is constructed. Iphidamas, the son of Antenor, is lying, and Koön is fighting for him against Agamemnon. On the shield of Agamemnon is Fear, whose head is a lion’s. The inscription above the corpse of Iphidamas runs: Iphidamas, and this is Koön fighting for him. The inscription on the shield of Agamemnon runs:

There is also Hermes bringing to Alexander the son of Priam the goddesses of whose beauty he is to judge, the inscription on them being:

Concerning their beauty, Hērā, Athena and Aphrodite.

On what account Artemis has wings on her shoulders I do not know; in her right hand she grips a leopard, in her left a lion. Ajax too is represented dragging Cassandra from the statue [agalma] of Athena, and by him is also an inscription: Ajax of Lokris is dragging Cassandra from Athena.

{5.20.7} A bronze tablet in front of it has the following elegiac inscription:

I, who once was a column in the house of Oinomaos;

Now by Kronos’ son I lie with these bands upon me,

A precious thing, and the baleful flame of fire consumed me not.

In my time another incident took place, which I will relate.

{5.22.3} These are the work of Lykios, the son of Myron, and were dedicated by the people of Apollonia on the Ionian sea. There are also elegiac verses written in ancient characters under the feet of Zeus:

Those who took the territory of the Abantes established these memorials here with the help of the gods [theoi], tithe from Thronion.

The land called Abantis and the town of Thronion in it were a part of the Thesprotian mainland over against the Ceraunian mountains.

{5.24.11} Homer proves this point clearly. For the boar, on the slices of which Agamemnon swore that Briseis had not lain with him, Homer says was thrown by the herald into the sea:

And the boar Talthybios swung and cast into the great depth

Of the grey sea, to feed the fishes.

Such was the ancient custom. Before the feet of the Oath-god is a bronze plate, with elegiac verses inscribed upon it, the object of which is to strike fear into those who take false oaths.

{5.25.10} An inscription too is written on the pedestal:

Descendants of Pelops the godlike offspring of Tantalos.

Such is the inscription on the pedestal, but the name of the artist is written on the shield of Idomeneus:

{5.25.13} On the offering of the Thasians at Olympia there is an elegiac couplet:

This Onatas, though belonging to the Aeginetan school of sculpture, I shall place after none of the successors of Daidalos or of the Attic school.

{5.27.2} The offerings at Olympia are two horses and two charioteers, a charioteer standing by the side of each of the horses. The first horse and man are by Dionysius of Argos, the second are the work of Simon of Aegina. [359] On the side of the first of the horses is an inscription, the first part of which is not metrical. It runs thus:

An Arcadian of Mainalos, now of Syracuse.

{5.27.12} The offering of the Mendeans in Thrace came very near to beguiling me into the belief that it was a representation of a competitor in the pentathlon. It stands by the side of Anauchidas of Elis, and it holds ancient jumping-weights. An elegiac couplet is written on its thigh:

Sipte seems to be a Thracian fortress and city. The Mendeans themselves are of Greek descent, coming from Ionia, and they live inland at some distance from the sea that is by the city of Ainos.

Scroll VI. Elis, Part 2

{6.3.14} A statue of Lysander, son of Aristokritos, a Spartan, was dedicated in Olympia by the Samians, and the first of their inscriptions runs:

I stand, dedicated at public expense by the Samians.”

So this inscription informs us who dedicated the statue; the next is in praise of Lysander himself:

Lysander, have you won, and are famed for valor.”

{6.4.6} Khilon, an Achaean of Patrai, won two prizes for men wrestlers at Olympia, one at Delphi, four at the Isthmus, and three at the Nemean Games. He was buried at the public expense by the Achaeans, and his fate it was to lose his life on the field of battle. My statement is borne out by the inscription at Olympia:

Three times at Nemeā, and four times at the Isthmus near the sea;

Khilon of Patrai, son of Khilon, whom the Achaean folk

Buried for my valor when I died in battle.”

{6.8.2} As to the boxer, by name Damarkhos, an Arcadian of Parrhasia, I cannot believe (except, of course, his Olympic victory) what romancers say about him, how he changed his shape into that of a wolf at the sacrifice of Lycaean [Wolf] Zeus, and how nine years after he became a man again. Nor do I think that the Arcadians either record this of him, otherwise it would have been recorded as well in the inscription at Olympia, which runs:

Parrhasian by birth from Arcadia.”

{6.9.8} The response given by the Pythian priestess was, they say, as follows:

Honor him with sacrifices as being no longer a mortal.”

So from this time have the Astypalaians paid honors to Kleomedes as to a hero.

{6.9.9} By the side of the chariot of Gelon is dedicated a statue of Philon, the work of the Aeginetan Glaukias. About this, Philon Simonides, the son of Leoprepes composed a very neat elegiac couplet:

The son of Glaukos, and I won two Olympic victories for boxing.”

There is also a statue of Agametor of Mantineia, who beat the boys at boxing.

{6.10.5} Who made the statue of Theopompos the wrestler we do not know, but those of his father and grandfather are said by the inscription to be by Eutelidas and Khrysothemis, who were Argives. It does not, however, declare the name of their teacher, but runs as follows:

Argives, who learned their art from those who lived before.”

Ikkos, the son of Nikolaidas of Tarentum, won the Olympic garland in the pentathlon and afterwards is said to have become the best trainer of his day.

{6.10.7} There are inscribed the names of the horses, Phoenix and Korax, and on either side are the horses by the yoke, on the right Knakias, on the left Samos. This inscription in elegiac verse is on the chariot:

After winning with his horses a victory in the glorious Games of Zeus.”

{6.11.8} Whereupon the Pythian priestess replied to them:

And when they could not think of a contrivance to recover the statue of Theagenes, fishermen, they say, after putting out to sea for a catch of fish caught the statue in their net and brought it back to land. The Thasians set it up in its original position, and are accustomed to sacrifice to him as to a god.

{6.13.10} The sons also of Pheidolas were winners in the horse race, and the horse is represented on a slab with this inscription:

Garlanded the house of the sons of Pheidolas.”

But the inscription is at variance with the Eleian records of Olympic victors. These records give a victory to the sons of Pheidolas at the sixty-eighth Festival but at no other. You may take my statements as accurate.

{6.14.10} For Sacadas won in the Games introduced by the Amphiktyones before a garland was awarded for success, and after this victory two others for which garlands were given, but at the next six Pythian Festivals Pythokritos of Sikyon was victor, being the only aulos player so to distinguish himself. It is also clear that at the Olympic Festival, he fluted six times for the pentathlon. For these reasons, the slab at Olympia was erected in honor of Pythokritos, with the inscription on it:

{6.17.6} That he was the soothsayer of the lineage of the Klutidai, Eperastos declares at the end of the inscription:

Their soothsayer, the scion of the god-like Melampodidai.”

For Mantios was a son of Melampos, the son of Amythaon, and he had a son, Oikles, while Klytios was a son of Alkmaion, the son of Amphiaraos, the son of Oikles. Klytios was the son of Alkmaion by the daughter of Phegeus, and he migrated to Elis because he shrank from living with his mother’s brothers, knowing that they had compassed the murder of Alkmaion.

{6.18.4} Then Anaximenes said,

Such were his words, and Alexander, finding no way to counter the trick, and bound by the compulsion of his oath, unwillingly pardoned the people of Lampsacus.

{6.19.6} There are placed here other offerings worthy to be recorded, the sword of Pelops with its hilt of gold, and the ivory horn of Amaltheia, an offering of Miltiades, the son of Kimon, who was the first of his house to rule in the Thracian Chersonesus. On the horn is an inscription in old Attic characters:

After they had taken the fortress of Aratos.

Their leader was Miltiades.”

There stands also a box-wood image of Apollo with its head plated with gold. The inscription says that it was dedicated by the people of Lokris who live near the Western Cape, and that the artist was Patrokles of Kroton, the son of Catillus.

{6.20.14} It was Kleoitas who originally devised the method of starting, and he appears to have been proud of the discovery, as on the statue in Athens he wrote the inscription:

He made me, Kleoitas the son of Aristokles.”

It is said that after Kleoitas some further device was added to the mechanism by Aristeides.

{6.22.6} The Eleians declare that there is a reference to this Pylos in the passage of Homer:

Alpheios, that in broad stream flows through the land of the Pylians.”

The Eleians convinced me that they are right. For the Alpheios does flow through this district, and the passage cannot refer to another Pylos. For the land of the Pylians over against the island Sphakteria simply cannot in the nature of things be crossed by the Alpheios, and, moreover, we know of no city in Arcadia named Pylos.

{6.25.3} Homer is quoted in support of the story, who says in the Iliad:

When the same man, the son of aegis-bearing Zeus,

Hit him in Pylus among the dead, and gave him over to pains.”

If in the expedition of Agamemnon and Menelaos against Troy, Poseidon was according to Homer an ally of the Greeks, it cannot be unnatural for the same poet to hold that Hades helped the Pylians. At any rate, it was in the belief that the god was their friend but the enemy of Hēraklēs that the Eleians made the sanctuary for him. The reason why they are accustomed to open it only once each year is, I suppose, because men too go down only once to Hades.

{6.26.4} Cyllene is one hundred and twenty stadium-lengths distant from Elis; it faces Sicily and affords ships a suitable anchorage. It is the port of Elis, and received its name from a man of Arcadia. Homer does not mention Cyllene in the list of the Eleians, but in a later part of the poem, he has shown that Cyllene was one of the towns he knew.

Comrade of Phyleides and ruler of the great-souled Epeians.”

In Cyllene is a sanctuary of Asklepios, and one of Aphrodite. But the image of Hermes, most devoutly worshipped by the inhabitants, is merely the male member upright on the pedestal.

Scroll VII. Achaea

{7.1.4} It so happened that the proposal found favor with Ion, and on the death of Selinous he became king of the people of Aigialos. He called the city he founded in Aigialos Helike after his wife, and called the inhabitants Ionians after himself. This, however, was not a change of name, but an addition to it, for the people were named ‘Ionians of Aigialos’. The original name clung to the land even longer than to the people; for at any rate in the list of the allies of Agamemnon, Homer [417] Is content to mention the ancient name of the land:

{7.5.3} So the Smyrnaeans sent ambassadors to Klaros to make inquiries about the circumstance, and the god made answer:

Who shall dwell in Pagus beyond the sacred Meles.”

So they migrated of their own free will, and believe now in two Nemeses instead of one, saying that their mother is Night, while the Athenians say that the father of the goddess [422] in Rhamnus is Okeanos.

{7.8.8} By prayers of all sorts, however, and by vast expenditure he secured from the Romans a nominal peace. The history of Macedonia, the power she won under Philip the son of Amyntas, and her fall under the later Philip, were foretold by the inspired Sibyl. This was her oracle:

To you the reign of a Philip will be both good and evil.

The first will make you kings over cities and peoples;

The younger will lose all the honor,

Defeated by men from west and east.”

Now those who destroyed the Macedonian empire were the Romans, dwelling in the west of Europe, and among the allies fighting on their side was Attalus … who also commanded the army from Mysia, a land lying under the rising sun.

{7.17.6} Its more ancient name was Paleia, but the Ionians changed this to its modern name while they still occupied the city; I am uncertain whether they named it after Dyme, a native woman, or after Dymas, the son of Aigimios. But nobody is likely to be led into a fallacy by the inscription on the statue of Oibotas at Olympia. Oibotas was a man of Dyme, who won the foot-race at the sixth Festival [450] and was honored, because of a Delphic oracle, with a statue erected in the eightieth Olympiad. [451] On it is an inscription which says:

Added to the renown of his fatherland Paleia.”

This inscription should mislead nobody, although it calls the city Paleia and not Dyme. For it is the custom of Greek poets to use ancient names instead of more modern ones, just as they surname Amphiaraos and Adrastos Phoronids, and Theseus an Erechthid.

{7.20.4} That Apollo takes great pleasure in oxen is shown by Alcaeus [455] in his hymn to Hermes, who writes how Hermes stole cows of Apollo, and even before Alcaeus was born Homer made Apollo tend cows of Laomedon for a wage. In the Iliad he puts these verses in the mouth of Poseidon:

A wide wall and very beautiful, that the city might be impregnable;

And thou, Phoebus, didst tend the shambling cows with crumpled horns.”

This, it may be conjectured, is the reason for the ox skull. On the marketplace, in the open, is an image of Athena with the tomb of Patreus in front of it.

{7.21.8} Various reasons could be plausibly assigned for the last of these surnames having been given to the god, but my own conjecture is that he got this name as the inventor of horsemanship. Homer, at any rate, when describing the chariot-race, puts into the mouth of Menelaos a challenge to swear an oath by this god:

That thou didst not intentionally, through guile, obstruct my chariot.”

{7.21.9} Pamphos also, who composed for the Athenians the most ancient of their hymns, says that Poseidon is

So it is from horsemanship that he has acquired his name, and not for any other reason.

{7.25.1} The disaster that befell Helike is but one of the many proofs that the wrath of the God of Suppliants is inexorable. The god at Dodona too manifestly advises us to respect suppliants. For about the time of Apheidas the Athenians received from Zeus of Dodona the following verses:

Of the Eumenides, where the Lacedaemonians are to be thy suppliants,

When hard-pressed in war. Kill them not with the sword,

And wrong not suppliants. For suppliants are sacred and holy.”

{7.25.12} By the Achaean Crathis once stood Aigai, a city of the Achaeans. In course of time, it is said, it was abandoned because its people were weak. [466] This Aigai is mentioned by Homer in Hērā’s speech:

Hence it is plain that Poseidon was equally honored at Helike and at Aigai.

{7.26.13} Between Aigeira and Pellene once stood a town, subject to the Sikyonians and called Donussa, which was laid waste by the Sikyonians;it is mentioned, they say, in a verse of Homer that occurs in the list of those who accompanied Agamemnon:

They go on to say that when Peisistratos collected the poems of Homer, which were scattered and handed down by tradition, some in one place and some in another, then either he or one of his colleagues perverted the name through ignorance.

{7.27.6} It is said too that when a war arose between Corinth and Pellene, Promakhos killed a vast number of the enemy. It is said that he also overcame at Olympia Poulydamas of Skotoussa, this being the occasion when, after his safe return home from the king of the Persians [Persai], he came for the second time to compete in the Olympic games. The Thessalians, however, refuse to admit that Poulydamas was beaten; one of the pieces of evidence they bring forward is a verse about Poulydamas:

Scroll VIII. Arcadia

{8.1.4} The Arcadians say that Pelasgus was the first inhabitant of this land. It is natural to suppose that others accompanied Pelasgus, and that he was not by himself; for otherwise he would have been a king without any subjects to rule over. However, in stature and in prowess, in beauty and in wisdom, Pelasgus excelled his fellows, and for this reason, I think, he was chosen to be king by them. Asios the poet says of him:

Black earth gave up, that the lineage of mortals might exist.”

{8.1.6} But he introduced as food the nuts of trees, not those of all trees but only the acorns of the edible oak. Some people have followed this diet so closely since the time of Pelasgus that even the Pythian priestess, when she forbade the Lacedaemonians to touch the land of the Arcadians, uttered the following verses:

Who will prevent you; though I do not grudge it you.”

It is said that it was in the reign of Pelasgus that the land was called Pelasgia.

{8.3.7} and Kallisto herself he turned into the constellation known as the Great Bear, which is mentioned by Homer in the return voyage of Odysseus from Calypso:

And the Bear, which they also call the Wain.”

But it may be that the constellation is merely named in honor of Kallisto, since her tomb is pointed out by the Arcadians.

{8.5.3} Afterwards Laodice, a descendant of Agapenor, sent to Tegea a robe as a gift for Athena Alea. The inscription on the offering told as well the lineage of Laodice :

Sending it to her broad fatherland from divine Cyprus.”

{8.7.6} The anger [mēnima] that comes from the god [theos] was not late in visiting him; never in fact have we known it more speedy. When he was but forty-six years old, Philip fulfilled the oracle that it is said was given him when he inquired of Delphi about the Persian [Persēs]:

Very soon afterwards events showed that this oracle pointed, not to the Persians, but to Philip himself.

{8.9.3} Praxiteles made the images Hērā is sitting, while Athena and Hērā’s daughter Hebe are standing by her side. Near the altar of Hērā is the tomb of Arkas, the son of Kallisto. The bones of Arkas they brought from Mainalos, in obedience to an oracle delivered to them from Delphi:

Arkas, from whom all Arcadians are named,

In a place where meet three, four, even five roads;

Thither I bid you go, and with kind heart

Take up Arkas and bring him back to your lovely city.

There make Arkas a precinct and sacrifices.”

This place, where the tomb of Arkas is, they call Altars of the Sun.

{8.10.10} Arkesilaos, an ancestor, ninth in descent, of Leokydes, who with Lydiades was general of the Megalopolitans, is said by the Arcadians to have seen, when dwelling in Lykosoura, the sacred deer, enfeebled with age, of the goddess called Lady. This deer, they say, had a collar round its neck, with writing on the collar:

This story proves that the deer is an animal much longer-lived even than the elephant.

{8.18.2} Epimenides of Crete, also, represented Styx as the daughter of Okeanos, not, however, as the wife of Pallas, but as bearing Echidna to Peiras, whoever Peiras may be. But it is Homer who introduces most frequently the name of Styx into his poetry. In the oath of Hērā he says :

And the water of Styx down-flowing.”

These verses suggest that the poet had seen the water of the Styx trickling down. Again in the list of those who came with Guneus [500] he makes the river Titaresios receive its water from the Styx.

{8.18.3} He also represents the Styx as a river in Hades, and Athena says that Zeus does not remember that because of her he kept Hēraklēs safe throughout the labors imposed by Eurystheus.

When he sent him to Hades the gate-keeper,

To fetch out of Erebos the hound of hateful Hades,

He would never have escaped the sheer streams of the river Styx.”

(8.25.1} As you go from Psophis to Thelpusa you first reach on the left of the Ladon a place called Tropaea, adjoining which is a grove, Aphrodisium. Thirdly, there is ancient writing on a slab:

In the Thelpusian territory is a river called Arsen (Male). Cross this and go on for about twenty-five stadium-lengths, when you will arrive at the ruins of the village Caus, with a sanctuary of Causian Asklepios, built on the road.

{8.25.4} After Thelpusa the Ladon descends to the sanctuary of Demeter in Onceium. The Thelpusians call the goddess Fury, and with them agrees Antimakhos also, who wrote a poem about the expedition of the Argives against Thebes. His verse runs thus:

Now Onkios was, according to tradition, a son of Apollo, and held sway in Thelpusian territory around the place Oncium; the goddess has the surname Fury for the following reason.

{8.25.8} They quote verses from the Iliad and from the Thebaid in confirmation of their story. In the Iliad there are verses about Areion himself:

The swift horse of Adrastos, who was of the lineage of the gods.”

In the Thebaid it is said that Adrastos fled from Thebes:

They will have it that the verses obscurely hint that Poseidon was father to Areion, but Antimakhos says that Earth was his mother:

The very first of the Danai to drive his famous horses,

Swift Caerus and Areion of Thelpusa,

Whom near the grove of Oncean Apollo

Earth herself sent up, a marvel for mortals to see.”

{8.25.10} But even though sprung from Earth the horse might be of divine lineage and the color of his hair might still be dark. It is also said that when Hēraklēs was warring on Elis he asked Oncus for the horse, and was carried to battle on the back of Areion when he took Elis, but afterwards the horse was given to Adrastos by Hēraklēs. Wherefore Antimakhos says about Areion:

{8.29.2} Homer does not mention giants at all in the Iliad, but in the Odyssey he relates how the Laestrygones attacked the ships of Odysseus in the likeness not of men but of giants, [511] and he makes also the king of the Phaeacians say that the Phaeacians are near to the gods like the Cyclopes and the lineage of giants. [512] In these places then he indicates that the giants are mortal, and not of divine lineage, and his words in the following passage are plainer still:

But he destroyed the infatuate folk, and was destroyed himself.”

“Folk” in the poetry of Homer means the common people.

{8.42.5} They cannot relate either who made this wooden image or how it caught fire. But the old image was destroyed, and the Phigalians gave the goddess no fresh image, while they neglected for the most part her festivals and sacrifices, until the barrenness fell on the land. Then they went as suppliants to the Pythian priestess and received this response:

In Phigaleia, the cave that hid Deo, who bare a horse,

You have come to learn a cure for grievous famine,

Who alone have twice been nomads, alone have twice lived on wild fruits.

It was Deo who made you cease from pasturing, Deo who made you pasture again

After being binders of wheat and eaters [530] of cakes,

Because she was deprived of privileges and ancient honors given by men of former times.

And soon will she make you eat each other and feed on your children,

Unless you appease her anger with libations offered by all your people,

And adorn with divine honors the nook of the cave.”

{8.42.9} These too are works of Onatas, and there are two inscriptions at Olympia. The one over the offering is this:

Once with the four-horse chariot, twice with the race-horse,

Hieron bestowed on thee these gifts: his son dedicated them,

Deinomenes, as a memorial to his Syracusan father.”

{8.42.10} The other inscription is:

Who had his home in the island of Aegina.”

Onatas was contemporary with Hegias of Athens and Ageladas of Argos.

{8.50.3} Not long afterwards the Argives celebrated the Nemean games, and Philopoimen chanced to be present at the competition of the harpists. Pylades, a man of Megalopolis, the most famous harpist of his time, who had won a Pythian victory, was then singing the Persians, an ode of Timotheus the Milesian. When he had begun the song:

the audience of Greeks looked at Philopoimen and by their clapping signified that the song applied to him. I am told that a similar thing happened to Themistocles at Olympia, for the audience there rose to do him honor.

{8.52.6} The inscription on the statue of Philopoimen at Tegea runs thus:

Many achievements by might and many by his counsels,

Philopoimen, the Arcadian spearman, whom great renown attended,

When he commanded the lances in war.

Witness are two trophies, won from the despots

Of Sparta; the swelling flood of slavery he stayed.

Wherefore did Tegea set up in stone the great-hearted son of Kraugis,

Author of blameless freedom.”

Scroll IX. Boeotia

{9.5.7} What I have said is confirmed by what Homer says in the Odyssey:

And built towers about it, for without towers they could not

Dwell in wide-wayed Thebe, in spite of their strength.”

Homer, however, makes no mention in his poetry of Amphion’s singing, and how he built the wall to the music of his harp. Amphion won fame for his music, learning from the Lydians themselves the Lydian mode, because of his relationship to Tantalos, and adding three strings to the four old ones.

{9.5.10} When Laios was king and married to Iocasta, an oracle came from Delphi that, if Iocasta bore a child, Laios would meet his death at his son’s hands. Whereupon Oedipus was exposed, who was fated when he grew up to kill his father; he also married his mother. But I do not think that he had children by her; my witness is Homer, who says in the Odyssey:

Who wrought a dreadful deed unwittingly,

Marrying her son, who slew his father and

Wedded her. But forthwith the gods made it known among men.”

How could they “have made it known forthwith,” if Epicaste had borne four children to Oedipus? But the mother of these children was Euryganeia, daughter of Hyperphas. Among the proofs of this are the words of the author of the poem called the Oedipodia; and moreover, Onasias painted a picture at Plataea of Euryganeia bowed with grief because of the fight between her children.

{9.11.1} On the left of the gate named Electran are the ruins of a house where they say Amphitryon came to live when exiled from Tiryns because of the death of Electryon; and the chamber of Alkmene is still plainly to be seen among the ruins. They say that it was built for Amphitryon by Trophonios and Agamedes, and that on it was written the following inscription:

Alkmene, he chose this as a chamber for himself.

Anchasian Trophonios and Agamedes made it.”

{9.14.3} and received the following response:

A care to me are the two sorrowful girls of Scedasus.

There a tearful battle is nigh, and no one will foretell it,

Until the Dorians have lost their glorious youth,

When the day of fate has come.

Then may Ceressus be captured, but at no other time.”

{9.15.6} On the statue of Epameinondas is an inscription in elegiac verse relating among other things that he founded Messene, and that through him the Greeks won freedom. The elegiac verses are these:

And holy Messene received at last her children.

By the arms of Thebe was Megalopolis encircled with walls,

And all Greece won independence and freedom.”

{9.17.5} Both these cities hold this belief, and they do so because of the oracles of Bacis, in which are the lines:

Pours on the earth peace-offerings of libation and prayer,

When Taurus is warmed by the might of the glorious sun,

Beware then of no slight disaster threatening the city;

For the harvest wastes away in it,

When they take of the earth, and bring it to the tomb of Phokos.”

{9.18.2} Quite close to it are three unfinished stones. The Theban antiquaries assert that the man lying here is Tydeus, and that his burial was carried out by Maeon. As proof of their assertion they quoted a line of the Iliad:

{9.18.5} There is also at Thebes the tomb of Hector, the son of Priam. It is near the spring called the Fountain of Oedipus, and the Thebans say that they brought Hector’s bones from Troy because of the following oracle:

If you wish blameless wealth for the country in which you live,

Bring to your homes the bones of Hector, Priam’s son,

From Asia, and reverence him as a hero, according to the bidding of Zeus.”

{9.20.2} There is a story that, as she reached extreme old age, her neighbors ceased to call her by this name, and gave the name of Graea (old woman), first to the woman herself, and in course of time to the city. The name, they say, persisted so long that even Homer says in the Catalogue:

Later, however, it recovered its old name.

{9.20.3} There is in Tanagra the tomb of Orion, and Mount Kerykion, the reputed birthplace of Hermes, and also a place called Polos. Here they say that Atlas sat and meditated deeply upon the things of the underworld and the things of the sky [ourania] , as Homer [575] says of him:

Of every sea, while he himself holds up the tall pillars,

Which keep apart earth and the sky [ouranos].

{9.29.1} Such is the truth about these things. The first to sacrifice on Helicon to the Muses and to call the mountain sacred to the Muses were, they say, Ephialtes and Otos, who also founded Ascra. To this also Hegesinos alludes in his poem Atthis:

Who when the year revolved bore him a son

Oioklos, who first with the children of Aloeus founded

Ascra, which lies at the foot of Helicon, rich in springs.”

{9.29.7} On the death of Linos, mourning for him spread, it seems, to all the barbarian world, so that even among the Egyptians there came to be a Linos song, in the Egyptian language called Maneros. Of the Greek poets, Homer shows that he knew that the sufferings of Linos were the theme of a Greek song when he says that Hephaistos, among the other scenes he worked upon the shield of Achilles, represented a boy harpist singing the Linos song:

Played with great charm, and to his playing sang of beautiful Linos.” [584]

{9.35.4} Pamphos was the first we know of to sing about the Graces, but his poetry contains no information either as to their number or about their names. Homer [591] (he too refers to the Graces) makes one the wife of Hephaistos, giving her the name of Grace. He also says that Sleep was a lover of Pasithea, and in the speech of Sleep there is this verse:

Hence some have suspected that Homer knew of older Graces as well.

{9.36.3} That the Phlegyans took more pleasure in war than any other Greeks is also shown by the lines of the Iliad dealing with Ares and his son Panic:

Or to the great-hearted Phlegyans.”

By Ephyrians in this passage Homer means, I think, those in Thesprotis. The Phlegyan people were completely overthrown by the god with continual thunderbolts and violent earthquakes. The remnant were wasted by an epidemic of plague, but a few of them escaped to Phokis.

{9.36.7} Hyettos is also mentioned by the poet who composed the poem called by the Greeks the Great Ehoiai:

In the halls, because of his wife’s bed;

Leaving his home he fled from horse-breeding Argos,

And reached Minyan Orkhomenos, and the hero

Welcomed him, and bestowed on him a portion of his possessions, as was fitting.”

{9.37.4} So going to Delphi he inquired of the oracle about children, and the Pythian priestess gave this reply:

Late thou camest seeking offspring, but even now

To the old plough tree put a new tip.”

Obeying the oracle he took to himself a young wife, and had children, Trophonios and Agamedes.

{9.38.4} So when the envoys landed, they saw, it is said, a rock not far from the road, with the bird upon the rock; the bones of Hesiod they found in a cleft of the rock. Elegiac verses are inscribed on the tomb:

The land of the horse-striking Minyans holds his bones,

Whose fame will rise very high in Greece

When men are judged by the touchstone of artistry.”

{9.38.7} The Thebans declare that the river Kephisos was diverted into the Orkhomenian plain by Hēraklēs, and that for a time it passed under the mountain and entered the sea, until Hēraklēs blocked up the chasm through the mountain. Now Homer too knows that the Cephisian Lake was a lake of itself, and not made by Hēraklēs. Wherefore Homer says:

{9.38.8} It is not likely either that the Orkhomenians would not have discovered the chasm, and, breaking down the work put up by Hēraklēs, have given back to the Gephisus its ancient passage, since right down to the Trojan war they were a wealthy people. There is evidence in my favor in the passage of Homer where Achilles replies to the envoys from Agamemnon:

a line that clearly shows that even then the revenues coming to Orkhomenos were large.

{9.38.9} They say that Aspledon was left by the inhabitants because of a shortage of water. They say also that the city got its name from Aspledon, who was a son of the nymph Mideia and Poseidon. Their view is confirmed by some verses composed by Chersias, a man of Orkhomenos:

Was born Aspledon in the spacious city.”

{9.40.5} Next to Lebadeia comes Khaironeia. Its name of old was Arne, said to have been a daughter of Aiolos, who gave her name also to a city in Thessaly. The present name of Khaironeia, they say, is derived from Khairon, reputed to be a son of Apollo by Thero, a daughter of Phylas. This is confirmed also by the writer of the epic poem, the Great Ehoiai:

Leipephilene, like in form to the Olympian goddesses;

She bore him in the halls a son Hippotes,

And lovely Thero, like to the moonbeams.

Thero, falling into the embrace of Apollo,

Bore mighty Khairon, tamer of horses.”

Homer, I think, though he knew that Khaironeia and Lebadeia were already so called, yet uses their ancient names, just as he speaks of the river Aigyptos, not the Nile. [596]

{9.41.3} However, I do not think that it is in the sanctuary of Adonis at Amathus. For the necklace at Amathus is composed of green stones held together by gold, but the necklace given to Eriphyle was made entirely of gold, according to Homer, who says in the Odyssey:

Not that Homer was unaware of necklaces made of various materials.

{9.41.4} For example, in the speech of Eumaios to Odysseus before Telemachus reaches the court from Pylos, he says:

With a necklace of gold strung with amber in between.”

{9.41.5} Again, in the passage called the gifts of Penelope, for he represents the wooers, Eurymakhos among them, offering her gifts, he says:

Of gold strung with pieces of amber, like the sun.”

But Homer does not say that the necklace given to Eriphyle was of gold varied with stones. So probably the scepter is the only work of Hephaistos.

Scroll X. Phokis, Ozolian Lokris

{10.1.4} The Thessalians, more enraged than ever against the people of Phokis, gathered recruits from all their cities and marched out against them. Whereupon the people of Phokis, rather terrified by the army of the Thessalians, especially by the number of their cavalry and by the disciplined training of both the horses and their riders, dispatched a mission to Delphi, asking the god how they might escape the danger that threatened them. And the oracular utterance [manteuma] that came back to them [from the Oracle] was this:

And to both will I give victory, but more to the mortal.

{10.4.5} Here at the ravine is the tomb of Tityos. The circumference of the mound is just about one-third of a stadium-length, and they say that the verse in the Odyssey:

refers, not to the size of Tityos, but to the place where he lay, the name of which was Nine Roods.

{10.5.6} There is extant among the Greeks an hexameter poem, the name of which is Eumolpia, and it is assigned to Musaeus, son of Antiophemus. In it, the poet states that the oracle belonged to Poseidon and Earth in common; that Earth gave her oracles herself, but Poseidon used Pyrcon as his mouthpiece in giving responses. The verses are these:

And with her Pyrcon, servant of the renowned Earth-shaker.

They say that afterwards Earth gave her share to Themis, who gave it to Apollo as a gift. It is said that he gave to Poseidon Kalaureia, that lies off Troizen, in exchange for his oracle.

{10.5.8} The verses of Boeo are:

By the sons of the Hyperboreans, Pagasus, and divine Agyieus.

After enumerating others also of the Hyperboreans, at the end of the hymn she names Olen:

And first fashioned a song of ancient verses.

Tradition, however, reports no other man as prophet but makes mention of prophetesses only.

{10.5.12} The rest of the story I cannot believe, either that the temple was the work of Hephaistos, or what they say about the golden singers, referred to by Pindar in his verses about this bronze temple:

These words, it seems to me, are but an imitation of Homer’s [606] account of the Sirens. Neither did I find the accounts agree of the way this temple disappeared. Some say that it fell into a chasm in the earth, others that it was melted by fire.

{10.6.7} Phemonoe, the prophetess of that day, gave them an oracle in hexameter verse:

At the spoiler of Parnassus; and of his blood guilt

The Cretans shall purify his hands; but the renown shall never die.

{10.7.6} What I say is confirmed by the votive offering of Ekhembrotos, a bronze tripod dedicated to the Hēraklēs at Thebes. The tripod has as its inscription:

When he won a victory at the Games of the Amphiktyones,

Singing for the Greeks tunes and lamentations.

In this way the competition in singing to the aulos [‘double-reed’] was dropped. But they added a chariot race, and Cleisthenes, the tyrant of Sikyon, was proclaimed victor in the chariot race.

{10.8.2} They say that Amphiktyon himself summoned to the common assembly the following lineages [gen ē]of the Greek people:

{10.8.9} Going up from the gymnasium along the way to the sacred space [hieron] [of Apollo] you reach, on the right of the way, the water of Castalia [Kastalia], which is sweet to drink and pleasant to bathe in. Some say that the spring [pēgē] was named after a native [epikhōrios] woman, others after a man called Castalius (Kastalios). But Panyassis son of Polyarkhos, who composed epic verses [epē] about Hēraklēs, says that Castalia was a daughter of Akhelōos. So, about Hēraklēs he [= Panyassis] says:

{10.9.9} Behind the offerings enumerated are statues of those who, whether Spartans or Spartan allies, assisted Lysander at Aigospotamoi. [613] They are these:

{10.9.10} These were made by Tisandros, but the next were made by Alypos of Sikyon, namely:

{10.9.11} The Athenians refuse to admit that their defeat at Aigospotamoi was fairly inflicted, maintaining that they were betrayed by Tydeus and Adeimantos, their generals, who had been bribed, they say, with money by Lysander. As a proof of this assertion, they quote the following oracle of the Sibyl [Sibulla]:

by Zeus the high thunderer, whose winning-power [kratos] is the greatest.

He [= Zeus} will imposeon the warships battle and fighting,

as they are destroyed by treacherous tricks, through the baseness of the captains.

The other evidence that they quote is taken from the oracles of Musaeus:

through the baseness of their leaders, but some consolation will there be

for the defeat; they shall not escape the notice of the city but shall pay the penalty [dikē].

{10.12.3} These statements she made in her poetry when in a frenzy and possessed by the god. Elsewhere in her oracles, she states that her mother was an immortal, one of the nymphs of Ida, while her father was a human. These are the verses:

An immortal nymph was my mother, my father, an eater of wheat;

On my mother’s side of Idaean birth, but my fatherland was red

Marpessus, sacred to the Mother, and the river Aidoneus.

{10.12.6} However, death came upon her in the Troad, and her tomb is in the grove of the Sminthian with these elegiac verses inscribed upon the tombstone:

Hidden beneath this stone tomb.

A maiden once gifted with voice, but now for ever voiceless,

By hard fate doomed to this fetter.

But I am buried near the nymphs and this Hermes,

Enjoying in the world below a part of the kingdom I had then.

The Hermes stands by the side of the tomb, a square-shaped figure of stone. On the left is water running down into a well and the images of the nymphs.

{10.12.10} Phaennis, daughter of a king of the Chaonians, and the Peleiai (Doves) at Dodona also gave oracles under the inspiration of a god, but they were not called by men Sibyls. To learn the date of Phaennis and to read her oracles […] for Phaennis was born when Antiokhos was establishing his kingship immediately after the capture of Demetrios. [620] The Peleiades are said to have been born still earlier than Phemonoe and to have been the first women to chant these verses:

Earth sends up the harvest, therefore sing the praise of Earth as Mother.

{10.13.8} The Delphians say that when Hēraklēs the son of Amphitryon came to the oracle, the prophetess Xenocleia refused to give a response on the ground that he was guilty of the death of Iphitos. Then Hēraklēs took up the tripod and carried it out of the temple. Then the prophetess said:

For before this, the Egyptian Hēraklēs had visited Delphi. On the occasion to which I refer, the son of Amphitryon restored the tripod to Apollo and was told by Xenocleia all he wished to know. The poets adopted the story and sing about a fight between Hēraklēs and Apollo for a tripod.

{10.14.5} The Greeks who fought against the king, besides dedicating at Olympia a bronze Zeus, dedicated also an Apollo at Delphi, from spoils taken in the naval actions at Artemisium and Salamis. There is also a story that Themistocles came to Delphi bringing with him for Apollo some of the Persian spoils. He asked whether he should dedicate them within the temple, but the Pythian priestess ordered him to carry them from the sanctuary altogether. The part of the oracle referring to this runs as follows:

Set not within my temple. Dispatch them home speedily.

{10.15.2} The second Apollo the Delphians call Sitalcas, and he is thirty-five cubits high. The Aetolians have statues of most of their generals, and images of Artemis, Athena, and two of Apollo, dedicated after their conclusion of the war against the Gauls. That the Celtic army would cross from Europe to Asia to destroy the cities there was prophesied by Phaennis in her oracles a generation before the invasion occurred:

The devastating host of the Gauls shall pipe; and lawlessly

They shall ravage Asia; and much worse shall the god do

To those who dwell by the shores of the sea

For a short while. For right soon the son of Cronos

Shall raise them a helper, the dear son of a bull reared by Zeus,

Who on all the Gauls shall bring a day of destruction.

By the son of a bull, she meant Attalus, king of Pergamon, who was also styled bull-horned by an oracle.

{10.18.1} The horse next to the statue of Sardus was dedicated, says the Athenian Kallias, son of Lysimakhides, in the inscription, by Kallias himself from spoils he had taken in the war against the Persians [Persai]. The Achaeans dedicated an image of Athena after reducing by siege one of the cities of Aetolia, the name of which was Phana. They say that the siege was not a short one, and being unable to take the city, they sent envoys to Delphi, to whom was given the following response:

Have come to inquire how ye shall take a city,

Come, consider what daily ration,

Drunk by the folk, saves the city which has so drunk.

For so ye may take the towered village of Phana.

{10.21.5} On this day, the Attic contingent surpassed the other Greeks in courage. Of the Athenians themselves, the bravest was Cydias, a young man who had never before been in battle. He was killed by the Gauls, but his relatives dedicated his shield to Zeus, God of Freedom, and the inscription ran:

The shield of a glorious man, an offering to Zeus.

I was the very first through which at this battle he thrust his left arm,

When the battle raged furiously against the Gaul.

{10.24.2} So these men wrote what I have said, and you can see a bronze statue of Homer on a slab, and read the oracle that they say Homer received:

You seek your fatherland; but no fatherland have you, only a motherland.

The island of Ios is the fatherland of your mother, which will receive you

When you have died; but be on your guard against the riddle of the young children.

The inhabitants of Ios point to Homer’s tomb in the island, and in another part to that of Clymene, who was, they say, the mother of Homer.

{10.24.3} But the Cyprians, who also claim Homer as their own, say that Themisto, one of their native women, was the mother of Homer, and that Euklos foretold the birth of Homer in the following verses:

Whom Themisto, lady fair, shall bear in the fields, A man of renown, far from rich Salamis.

Leaving Cyprus, tossed and wetted by the waves,

The first and only poet to sing of the woes of spacious Greece,

For ever shall he be deathless and ageless.

These things I have heard, and I have read the oracles, but express no private opinion about either the age or date of Homer.

{10.25.1} Beyond the Cassotis stands a building with paintings of Polygnotus. It was dedicated by the people of Knidos, and is called by the Delphians Lesche (Place of Talk), because here in days of old they used to meet and talkabout the more serious matters and things that had to do with myth. That there used to be many such places all over Greece is shown by Homer’s words in the passage where Melantho abuses Odysseus:

Nor yet to the place of talk, but you make long speeches here.

{10.27.4} By the latter stands Antenor, and next to him Crino, a daughter of Antenor. Crino is carrying a baby. The look upon their faces is that of those on whom a calamity has fallen. Servants are lading an donkey with a chest and other furniture. There is also sitting on the donkey a small child. At this part of the painting, there is also an elegiac couplet of Simonides:

Painted a picture of Troy’s citadel being sacked.

{10.28.2} Polygnotus followed, I think, the poem called the Minyad. For in this poem occur lines referring to Theseus and Peirithoös:

For this reason then, Polygnotus too painted Kharon as a man well stricken in years.

{10.29.10} The proverbial friendship of Theseus and Peirithoös has been mentioned by Homer in both his poems. In the Odyssey, Odysseus says to the Phaeacians:

Theseus and Peirithoös, renowned children of gods.

And in the Iliad, he has made Nestor give advice to Agamemnon and Achilles, and speaking among others the following verses:

As were Peirithoös, Dryas, shepherd of the folk,

Kaineus, Exadios, god-like Polyphemos,

And Theseus, son of Aigeus, like to the immortals.

{10.31.4} The story about the brand, how it was given by the Fates to Althaea, how Meleagros was not to die before the brand was consumed by fire, and how Althaea burned it up in a passion—this story was first made the subject of a drama by Phrynichus, the son of Polyphradmon, in his Pleuronian Women:

However, it appears that Phrynichus did not elaborate the story as a man would his own invention but only touched on it as one already in the mouths of everybody in Greece.

{10.33.7} The land beside the Kephisos is distinctly the best in Phokis for planting, sowing and pasture. This part of the district, too, is the one most under cultivation, so that there is a saying that the verse,

alludes, not to a city Parapotamii (Riverside), but to the farmers beside the Kephisos.

{10.37.6} So the Amphiktyones determined to make war on the Cirrhaeans, put Cleisthenes, tyrant of Sikyon, at the head of their army, and brought over Solon from Athens to give them advice. They asked the oracle about victory, and the Pythian priestess replied:—

Until on my precinct shall dash the wave

Of blue-eyed Amphitrite, roaring over the winedark sea.

So Solon induced them to consecrate to the god the territory of Cirrha, in order that the sea might become neighbor to the precinct of Apollo.