2025.06.19 | By Gregory Nagy

This is the text of a talk I am presenting on the second day of the conference titled “Female voices in a public context: authorial articulation and mimetic representation in ancient Greek literature,” held at the Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” on June 24–26.

(8th Open Conference of the Network for the Study of Archaic and Classical Greek Song)

Abstract.

In a recent article published in Cambridge Classical Journal (68 [2022] 49–82) and titled “The Afterlife of Sappho’s Afterlife,” Giambattista D’Alessio has re-examined a poetic theme, not directly attested in the surviving fragments of Sappho, where the poet pictures herself as plunging from on high, from the summit of a looming white rock, into the sea below. It appears that she is suffering from unrequited love, having been abandoned by a beautiful young man named Phaon, and it also appears that her “lover’s leap” is fatal. But appearances can be deceiving. We are dealing here with a poetic theme, as D’Alessio shows, and this theme is an aspect of what he describes as a poetics of eschatology, where the songs of Sappho are imagined as destined for an afterlife after her death—and where the poet herself is destined for a personal afterlife by way of recovering the love of the love-object that had been fleeing her, namely, her beloved Phaon. In support of such an argument, I offer in my talk here some further comments, where I connect the poetic theme of Sappho’s professed love for Phaon with related themes. One such related theme centers on myths about the love of the goddess Aphrodite herself for the beautiful Phaon—as also for another beautiful young man named Adonis, who represents a generalized version of a more localized figure like Phaon. I describe Phaon here as “more localized” because, as a native son of Lesbos, this figure occupied a central role in the myths of that island.

I should add that my comments in this talk involve not only Sappho’s Adonis and Sappho’s Phaon—attested or non-attested in the surviving songs of Sappho—but also these same two figures as definitely attested in classical Athenian vase-paintings that were inspired, I will argue, by songs of Sappho as actually performed in Athens. These comments here are mostly derived from Essay 8 and Essay 9 of a book that has already been published online in 2023 and will be published in print this year, 2025, in Athens. The title of that book, to cite it short-hand here, is Sappho I, and I also cite here a link that takes the reader to a free online version:

https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu/sappho-i-version-alpha-via-beta/

I start my talk by showing two featured images. The first of the two is a painting that goes by the title Safo, by Miguel Carbonell Selva, dated 1881, where we see the figure of Sappho at the moment when she is about to leap to her mythologized death, plunging into the sea from the heights of a headland named Leukas. Her death seems to be happening at sunset:

The timing of sunset is more explicit in a the second of my two featured images, which is a painting by Gustave Moreau, dated around 1893:

These pictures lead me, from the start, to ask one overriding question: why sunset?

§1. The story about a fatal leap of Sappho into the sea at a headland named Leukas (latinized as Leucas), which means ‘White Rock’, is best known today from a Latin version that we can read in a collection of elegiac poems by the Roman poet Ovid about female heroes, the Heroides. This Latin version is Heroides 15, which fictionalizes a plaintive letter written by a lovesick Sappho before she takes a fatal leap into the sea, plunging from the heights of Leukas / Leucas (lines 163–172, 220). Her letter is addressed to a beautiful young male lover of hers—he is named as Phaon—whom she tearfully reproaches for having abandoned her and having voyaged off to parts West. Although the attribution of Heroides15 to Ovid has been questioned (Tarrant 1981), the artistry of this poem has been much admired—and it merits being described as Ovidian (Peponi 2018, with extensive bibliography). For example, in the first of the two paintings that I show as featured images for this talk, I highlight one detail that seems obviously inspired by a most Ovidian visual effect that we see achieved in the verbal art of Heroides 15. It is the sight of Sappho’s disheveled tresses, as lovingly described at line 73: ecce, iacent collo sparsi sine lege capilli ‘just look how they are arranged, all over the nape of my neck, those lawlessly disheveled tresses of mine’. There is a playful oxymoron at work here, since the form iacent, which I translate as ‘are arranged’, would ordinarily refer to a carefully arranged hairdo, whereas Sappho’s hair is at this moment ‘lawlessly’ and thus erotically disheveled, disarranged. As Charles Murgia (1985:456–457) has noted, the verb iaceō that we see here, as the third-person-plural form iacent ‘are arranged’, is used as the passive “voice” of the active verb pōnō (corresponding to the Greek usage of κεῖμαι as the functional passive of active τίθημι), and this verb pōnō ‘put, place, arrange’ can refer to the art of making a hairdo, as it were, for unruly hair. A fine example is the wording we find in Ovid’s Heroides 4.77, with reference to the beautiful locks of the boy hero Hippolytus, love-object of Phaedra: positi […] sine arte capilli ‘locks of hair arranged [verb pōnō] without artifice’. I cite also an imitative reference to the hair of Hippolytus, compared to the unruly locks of Apollo himself, in Seneca’s Phaedra 803–804: coma | nulla lege iacens ‘a head of hair, in an unruly way arranged’. The oxymoron, then, is that the verbal art of the poet has artfully arranged the disarrangement of a would-be hairdo. And, evidently, there is a parallel artistic arrangement going on in the visual art of the painter who depicts the disarrangement of Sappho’s hair in the painting I show as the first featured image for this talk.

§2. I have indulged myself here in dwelling on the artistry of the moment, focusing on “A Death of a Maiden at Sunset.” But I concentrate not on the artistic merits of Heroides 15 but rather on the mass of learned references that the poet is making to the poetics of Sappho. In my studies on Sappho, I have found these references to be a most valuable source of information in my efforts to reconstruct what Sappho must have said about Phaon in her songs. In my book Sappho 0 (2§§59–61), I summarize more briefly the results of my reconstruction, but now, summarizing the more extensive reconstruction that I attempt in Essay 8 pf my book Sappho I, I will need to go into more detail. In any case, for those interested in how I make my extensive arguments in both those online books, which as I say have been in circulation since 2023, along with a third book, Sappho II, I note here the link to Classical Continuum, https://continuum.fas.harvard.edu, where all three books are available to all, gratis. I also take this opportunity, before I get into details, to pay homage to five extraordinarily collegial friends who have edited with me all three of my books on Sappho. I list these friends here in a sequence that reflects a chronological order of their celestial involvement: Claudia Filos, Noel Spencer, Keith DeStone, Arin Jones, and Leonard Muellner.

§3. That said, I start reviewing my efforts to reconstruct what the songs of Sappho must have said about Phaon by focusing on the celestial associations, in her songs, of Sappho herself with the goddess Aphrodite. We can already see in Song 1 of Sappho, for example, how the celestial Aphrodite descends from the heavens to converse with our earthbound Sappho, making it possible for the maker of the song to achieve a personalized contact with the roles of the goddess in the world of myth.

§4. One particular celestial role of Aphrodite that I find particularly relevant is the identification of Aphrodite, in the poetics of Sappho, with the planet Venus, that is, with the planet called Aphrodite in Greek, whose celestial body is imagined as the force that makes the sun rise (I refer to this myth in a book published in 1990, Greek Mythology and Poetics, page 258, where I also refer to an earlier analysis, published already in 1973, which is kindly cited by Giambattista D’Alessio in the article of his that I cited at the beginning). This heavenly identification of Aphrodite, as we will now see, leads to a poetic self-identification imagined by Sappho: she imagines herself as falling in love with a beautiful young Aeolian hero named Phaon just as the goddess Aphrodite in her role as the planet Venus falls in love with the same hero (Greek Mythology and Poetics pp. 258–262). The name Phaōn, stemming from the Aeolic dialect of Lesbos, is the local Aeolian equivalent of the Ionic adjective phaethōn ‘shining’, which is the poetic epithet of the sun in Homeric diction (as I argue in a 1996 book, Poetry as Performance, pp. 90, 102–103).

§5. As I have argued at length in an essay I already cited—the one that goes back to 1973 and was republished in the 1990 book Greek Mythology and Poetics (where the relevant pages are 228–230, 258–262), Sappho’s love for the beautiful young Aeolian hero Phaon is modeled on a myth about the love of the goddess Aphrodite herself for this hero. Before I consider this myth here again, however, I need to preview another myth that will help us better understand the meaning of both myths. That other myth is attested in a narration by Ptolemaios Chennos (first/second centuries CE), as epitomized by Photius (Bibliotheca codex 190, page 153 ed. Bekker), where we read that Aphrodite undergoes a mock death by performing a “lover’s leap” from the heights of the same White Rock, Leukas, into the sea below. In that other myth, what drives Aphrodite to take the plunge is her passionate love for another beautiful young hero. But that hero, unlike the beautiful young hero Phaon, is not an Aeolian hero. He is Adonis.

§6. As I will now argue, the role of the beautiful Adonis as a love-object of a pursuing Aphrodite is matched by the role of the beautiful Phaon, who is likewise a love-object pursued by the goddess. Here I paraphrase the relevant testimonia (Sappho F 211 ed. Voigt):

§7. According to a myth originating from the island of Lesbos, an old man named Phaon was a porthmeús ‘ferryman’ who was transformed into a beautiful youth by Aphrodite herself. The goddess had disguised herself as an old woman and persuaded the old ferryman to ferry her across a narrow strait separating the mainland of Asia Minor from the island of Lesbos. Then the goddess fell in love with the beautiful young Phaon and hid him in a head of lettuce. This myth is attested in many sources, including the antiquarian Athenaeus (2.69d–e), who cites as his own source a master of Old Comedy, Cratinus (F 370 ed. Kassel/Austin). But this same antiquarian, Athenaeus (again, 2.69d–e), also cites later sources where it is the non‑Aeolian hero Adonis and not the Aeolian hero Phaon who is hidden in a head of lettuce by Aphrodite (Eubulus F 13 ed. Kassel/Austin and Callimachus F 478 ed. Pfeiffer).

§8. This thematic parallelism of Aphrodite and her Aeolian lover Phaon on the one hand with Aphrodite and her non‑Aeolian lover Adonis on the other hand becomes most important as I now dive into further details in the myth I already mentioned about Aphrodite and Adonis.

§9. I return to the myth as narrated by Ptolemaios Chennos (first/second centuries CE) and as epitomized by Photius Bibliotheca codex 190, page 153 ed. Bekker. According to this narrative, the first to leap down into the sea from the heights of Cape Leukas was none other than Aphrodite herself, out of love for a dead Adonis. After Adonis died (how it happened is not said), the mourning Aphrodite went off searching for him and finally found him at a sacred precinct of the god Apollo in Cyprus. Apollo instructs Aphrodite to seek relief from her love by diving into the sea from the heights of the White Rock of Leukas, where Zeus sits whenever he wants relief from his own passion for Hera. Then the narrative launches into a veritable catalogue of other figures who followed Aphrodite’s precedent and took a ritual plunge as a remedy for love.

§10. I argue that the figure of Sappho, modeling herself on Aphrodite, could actually picture herself, in her songs, as taking a lover’s leap by diving from the heights of the White Rock of Leukas into the sea below, as if she were crazed with love for Phaon—just as Aphrodite was crazed with love for Phaon—or for Adonis. And, just like Aphrodite, Sappho too could be crazed with love either for the beautiful Adonis or for the beautiful Phaon. At later points in my book, Sappho I (9§§4–12, 10§§1–7), I show in some detail the bivalence of Sappho’s poetics in expressing her love either for Phaon or for Adonis. When it comes to a lover’s leap of Sappho, however, as modeled on a lover’s leap by Aphrodite, we have a direct attestation only for Phaon as the love-object who inspires Sappho’s own plunge from the heights of the White Rock of Leukas. As we learn from the ancient testimonia about Sappho (T 23 ed. Campbell), the geographer Strabo 10.2.9 C452 quotes the relevant lines from a comedy of Menander (F 1 ed. Austin 2013). Like Aphrodite, Sappho is pictured in these lines as leaping from the White Rock of Leukas into the sea below, crazed as she is with love for Phaon. Here is the quotation from the play of Menander, as provided by Strabo 10.2.9 C452:

οὗ δὴ λέγεται πρώτη Σαπφὼ

τὸν ὑπέρκομπον θηρῶσα Φάον’

οἰστρῶντι πόθῳ ῥῖψαι πέτρας

ἀπὸ τηλεφανοῦς. [[ἀλλὰ]] κατ’ εὐχὴν

[[σήν]], δέσποτ’ ἄναξ, εὐφημείσθω

τέμενος πέρι Λευκάδος ἀκτῆς

Menander F 1 ed. Austin 2013

… where they say that Sappho was the first,

pursuing the proud Phaon,

to throw herself, in her goading desire, from the rock

that shines from afar. [[But now,]] in accordance with [[your]] sacred utterance,

lord king, let there be reverence in speech

throughout the sacred precinct of the headland of Leukas.

Both in the Greek text and in the corresponding translation, I enclose within double-square brackets those aspects of the wording that are textually uncertain. For details about the uncertainties, I refer to the incisive article by Giambattista D’Alessio (2022). But these uncertainties, which involve only the lines that follow the four lines about Sappho herself, are not relevant to my argumentation here. Directly relevant, on the other hand, is what D’Alessio observes about a stunning image discovered in the stucco decorations of the so-called Underground “Neo-Pythagorean” Basilica near Porta Maggiore in Rome (dating back to the first half of the first century CE): I agree with D’Alessio that we see there a picturing, at a focal point in the decorations, an image of Sappho herself in the act of leaping from the White Rock of Leukas.

§11. The four lines referring to Sappho’s leaping from the promontory of Leukas into the sea below, driven as she is by her passionate love of Phaon, stem from a play of Menander’s that is actually named after Leukas, the Leukadiā, meaning ‘the girl from Leukas’. We are told here in Menander’s four lines that Sappho leapt off the White Rock of Leukas in pursuit of Phaon. Strabo quotes these revealing lines (10.2.9 C452) simply as a piece of poetic lore that he links with non-poetic lore about a prominent white rock jutting out into the sea from the heights of a promontory named Leukatās at the southwestern tip of the Ionian island named Leukas, latinized as Leucas (which is in turn situated to the north of two other famous Ionian Islands, Cephalonia and Ithaca). The heights of this promontory can best be described as a chalk cliff, or, more broadly, as a ‘white rock’, and the island of Leukas itself is actually named metonymically after this ‘White Rock’, which is also known as Leukas petrā or as Leukatās or, today, as ‘Cape Leucas’. In the reportage of Strabo, the geographer is obviously skeptical about accepting the story of Sappho’s leap at Cape Leucas as a historical fact, as if Sappho herself had really been the first to take a lover’s leap from the aktē or ‘headland’ named Leukas, as we read in Menander’s own words.

§12. In any case, the real historical fact, as I will now go on to argue, is that the very idea of a lover’s leap by Sappho, driven by love for Phaon, was actually attested in the textual tradition of Sappho.

§13. Following Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff (1913:25–40.), I think that Menander chose for his play a setting that was known for its exotic cult practice involving a white rock and conflated it in the quoted passage with a literary theme likewise involving a white rock. And I point to two surviving attestations of this theme. The first is from lyric:

ἀρθεὶς δηὖτ’ ἀπὸ Λευκάδος

πέτρης ἐς πολιὸν κῦμα κολυμβῶ μεθύων ἔρωτι

Anacreon PMG 376

Once again this time taking off in the air, down from the White

Rock into the dark waves do I dive, intoxicated with love [erōs].

The second is from Euripides:

ὡς ἐκπιεῖν γ’ ἂν κύλικα μαινοίμην μίαν

πάντων Κυκλώπων <μὴ> ἀντιδοὺς βοσκήματα

ῥῖψαί τ’ ἐς ἅλμην Λευκάδος πέτρας ἄπο

ἅπαξ μεθυσθεὶς καταβαλών τε τὰς ὄφρυς.

ὡς ὅς γε πίνων μὴ γέγηθε μαίνεται

Euripides Cyclops 163–168

in return for drinking one cup [of that wine]

and throw myself from the white rock into the sea,

once I am intoxicated, with eyebrows relaxed.

Whoever is not happy when he drinks is crazy.

(For a discussion of the restoration <μὴ>, I cite Wilamowitz pp. 30–31n2.)

§14. In both these passages, the experience of plunging from a white rock is parallel to the sensation of falling into a swoon—be it from intoxication or from making love. As for Menander’s allusion to Sappho’s plunge from the heights of Leukas in the generic sense of a ‘white rock’, Wilamowitz (pp. 33–37) infers that there must have existed a similar theme, which does not survive, in the poetry of Sappho. Within the framework of this theme, the female speaker must have pictured herself as driven by love for a certain Phaon, or at least so it was understood by the time of Menander.

§15. Having followed Wilamowitz so far, I will now go one step further. In the case of the passage I quoted from Anacreon, I will argue that the wording here is not just a literary trope that happens to be parallel to the unattested wording of Sappho: rather, the wording is a direct imitation of Sappho’s wording. As I have pointed out elsewhere in Sappho I, in Essay 5§12, the use of the word dēute in the sense of ‘once again this time’ in the fragment I quoted from Anacreon is parallel to the triple use of the same word in Song 1 of Sappho. But I also argued, even earlier in that book, already in Essay 2§13, that the very act of singing a song of Anacreon at a symposium could be viewed as parallel to singing a song of Sappho herself. In making that argument, I quoted this most revealing formulation in the Sympotic Questions of Plutarch (711d): ὅτε καὶ Σαπφοῦς ἂν ᾀδομένης καὶ τῶν Ἀνακρέοντος ἐγώ μοι δοκῶ καταθέσθαι τὸ ποτήριον αἰδούμενος ‘whenever Sappho is being sung, and Anacreon, I think of putting down the drinking cup in awe’. In Essays 24 and 25 of Sappho I, I extend this argument much further.

§16. For now, however, I concentrate on what I see as a direct reference to unattested words of Sappho in the attested words of Menander, which point to the relevant poetic agenda of Sappho. We see here Sappho figuring herself as a projection of Aphrodite. In the myth about Aphrodite and Phaon, as we have seen at §7 above, the goddess turns into an old woman and then turns the old man Phaon into a young man, but then she can once again turn back into an eternally young goddess in her fond desire to turn him into her eternally young lover. The hope, in the poetics of Sappho, is to share with Aphrodite the same fond desire.

§17. As I noted from the start, there is a comparable interpretation by Giambattista D’Alessio (2022) in his re-examination of the theme of Sappho’s leap into the sea at Cape Leukas out of love for Phaon, as prominently mentioned in Fragment 1 of Menander’s Leukadiā. He argues, as I also noted, that this theme is an aspect of what can be described as a poetics of eschatology, where the songs of Sappho are imagined as destined for an afterlife after her death—and where the poet herself is destined for a personal afterlife by way of recovering the love of the love-object that had been fleeing her, namely, her beloved Phaon.

§18. In support of such an argument, I offer—in essays that follow my Essay 8 of Sappho I as epitomized here—further argumentation about the poetics of Sappho in identifying with the love of the goddess Aphrodite herself for Phaon—as also for Adonis, who as I already said represents a more generalized version of a figure like Phaon, localized as he is on the island of Lesbos. The argumentation focuses on relevant details found both in the songs of Sappho and in Athenian vase-paintings that were inspired, as I argue, by songs of hers as they were performed at symposia as well as in citharodic competitions at the festival of the Panathenaia in Athens.

§19. In Essay 8, however, I first deal with further details in the text of Heroides 15, which is evidently a main source of inspiration for the second of the two paintings that I have shown at the beginning of this talk.

§20. I now return to one explicit detail that we see in the second painting. It is the sunset that frames the fatal leap of Sappho. This detail, I think, can be linked more generally to the myth underlying the professed love of Sappho for Phaon, and this myth, I further think, is what may have inspired the painter to synchronize the setting of the sun with the death of Sappho.

§21. This myth, native to the island of Lesbos, homeland of Sappho, is about Phaon as a beautiful boy who was loved, once upon a time, by the goddess Aphrodite. And the meaning of this boy’s name is relevant to sunset, because Pháōn is a “speaking name,” a nomen loquens. Quite transparently, Pháōn means ‘shining [like the sun]’. And, as I showed long ago in my essay about the poetics of Sappho (Nagy 1973), Sappho’s solar boy Pháōn is parallel to another celebrated solar boy in Greek myth, whose name is Phaéthōn—a name that likewise means ‘shining [like the sun]’. In fact, there is evidence for the existence of at least two different myths about two different solar boys named Phaethon, but I limit myself here to only one detail about only one of these boys: in the Hesiodic Theogony 986–991, we read that the goddess Aphrodite abducted this solar boy.

§22. Aside from his link with Aphrodite, I will spare further details here about this solar boy Phaethon and return to that other solar boy, Sappho’s Phaon. As I also showed in the essay I mentioned in the previous paragraph (again Nagy 1973), the poetics of Sappho visualized Phaon as the setting sun personified, who is pursued at sunset by the planet Venus. This planet, which as I already noted was for Sappho the planet Aphrodite, was visualized as setting into the dark waters of the Western horizon after sunset, evidently in pursuit of the solar boy Phaon. Just as Aphrodite was madly in love with Phaon, so also Sappho, by projection, could fall madly in love with the sun, source of her poetic eroticism, and so the poetess in her reveries could take her own plunge from on high, at sunset, down into the dark waters below.

§23. The sun, which I have just described as the source of Sappho’s poetic eroticism, is actually highlighted as the love-object of her passionate yearning, which is eros, as we read in the final two lines of Sappho’s Tithonos (in the version of the Oxyrhynchus Papyrus, not in the version of the Cologne Papyrus):

⸤ἔγω δὲ φίλημ’ ἀβροϲύναν, …⸥ τοῦτο καί μοι | τὸ λά⸤μπρον ἔρωϲ ἀελίω καὶ τὸ κά⸥λον λέ⸤λ⸥ογχε.

Sappho’s Tithonos 15–16

But I love luxuriance [(h)abrosunē] […] this, | and passionate-love [erōs] for the Sun has won for me its radiance and beauty.

My translation of lines 15–16 here is based on the reading ἔρωϲ ἀελίω, as I argue in Greek Mythology and Poetics (1990:261–262), instead of a commonly accepted emendation ἔροc τὠελίω. In terms of the first reading, ἔρωϲ ἀελίω, the Sun is the objective genitive of erōs, ‘passionate-love’. In terms of the second reading, ἔροc τὠελίω, the translation would be … ‘passionate-love [eros] has won for me the radiance and beauty of the Sun’. I agree with Camillo Neri (2021:676), who argues for the first reading and against the second reading.

[9§0.] Before I reach the end of my talk, I need to show two more images—this time from vase paintings produced in Athens by an unnamed artist, dating back to the fifth century BCE, who is known to art historians simply as “the Meidias Painter.” I am looking here for traces of pictorial references to the contents of Sappho’s songs as performed in the city-state of Athens during the Classical period, in the fifth century BCE and beyond. In other words, I am looking for aspects of Sappho’s songs that Athenians of that era would have remembered from hearing these songs being performed at symposia and even at public concerts—especially at the festival of the Great Panathenaia. But we are faced with a problem whenever we consider more closely this kind of remembrance by audiences—and even by the painters who were surely part of such audiences. Just as the painters of Classical Athens, masters of their visual art, would have tuned in, as it were, to the masters of verbal art who transmitted, in performance, the songs of Sappho, these painters would have been no different from the general audiences if they also remembered many other kinds of relevant songs besides those of Sappho, and their references to any and all such songs in any single painting would not need to be compartmentalized. So, whenever we happen to see in any given painting some detail that corresponds to a detail we read in a surviving text of Sappho—or even in some later text where Sappho is being imitated—we cannot really expect such painted details to be restricted to any single song attributed to Sappho or to any other maker of songs, as if such a song were merely a text. Instead, we do need to expect, in any given painting, a possible mixing of different details heard in different songs. Such mixing, however, would not disprove the reality of references actually made in visual art to specific details that would be heard in verbal art. As my first example of such a reality, I show here a close-up from an Athenian painting that dates back to the fifth century BCE. The painter is the Meidias Painter.

[9§1.] I comment on this close-up in the light of the overall painting, which the reader may view by consulting the available images in the Beazley Archive. In the close-up that I show here, we see pictured the youthful hero Phaon, renowned for his beauty and made famous in the songs of Sappho—his identity is guaranteed by the lettering ΦΑΩΝ (not visible in the close-up), placed next to the painted figure. Phaon is shown playing his music on a lyre while sitting inside a luxuriant bower and enjoying the attentive company of a lady named Demonassa, who is identified by way of lettering similarly placed next to her beautiful figure. There is no question here, to my mind, that this Phaon is Sappho’s Phaon. As I have been arguing, Phaon was featured as a primary love object for Sappho—that is, for her poetic persona. For Sappho, Phaon was an ultimate emblem of unrequited love, and this aspect of Sappho’s poetics is still most clearly visible in the Ovidian poem Heroides 15. But who was Demonassa? Was she too featured in the songs of Sappho? Given the sadly fragmentary state of the textual tradition of Sappho, we cannot be certain: she may have been a figure in songs of Sappho that are lost to us—or maybe not. But my argument, in any case, is that her presence in the painting is relevant to the poetics of Sappho, as we can see from the context of the overall painting from which I have highlighted this close-up.

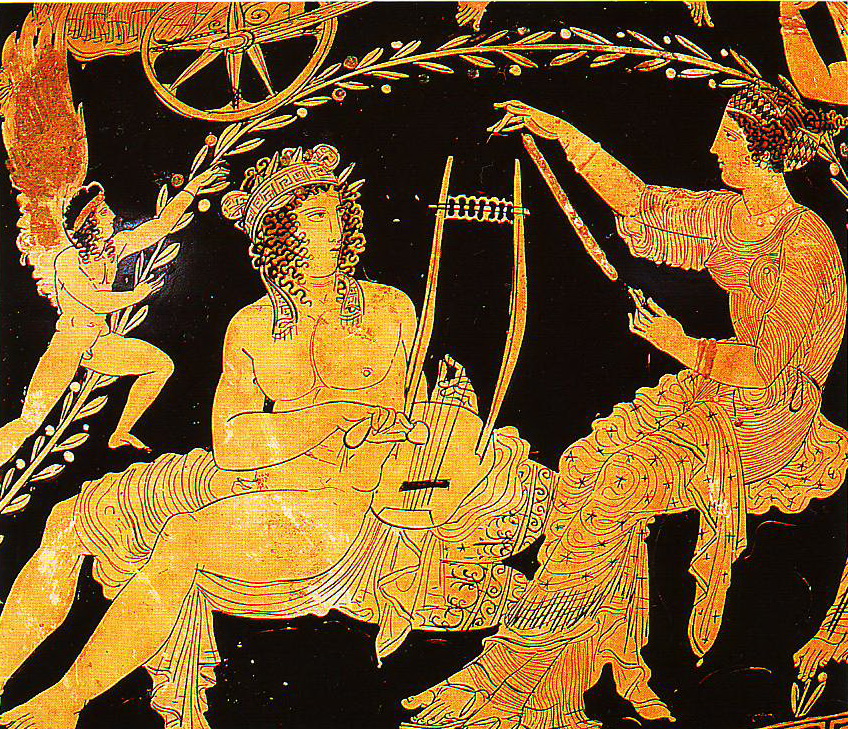

[9§2.] The context of the painting highlights an amorous atmosphere enjoyed by an ensemble of ladies pictured in the painting, including Demonassa. The amorousness of these ladies is explicitly signaled by the presence of the goddess of love incarnate, Aphrodite herself: she is shown driving a chariot drawn by two naked adolescent ‘cupids’ or eros-figures, whose names are inscribed into the painting: the two figures are personified by way of their inscribed names Himeros and Pothos, both meaning ‘longing, desire’. Here is a close-up of Aphrodite and her ‘cupids’:

[9§5.] Besides Phaon, another love-object of the goddess Aphrodite is the beautiful youthful hero Adonis, as pictured in another related Athenian painting. Again, the painter is the Meidias Painter/

[9§6.] In this picture, we see Adonis (the lettering says ΑΔΩΝΙΟΣ) embraced from behind by Aphrodite (ΑΦΡΟΔΙΤΗ) on our right while on our left he is being prompted into erotic action by a winged Eros named Himeros ‘longing, desire’ who is hovering overhead. Further to our left, an attending lady named Eurynoe (ΕΥΡΥΝΟΗ) is teasing her pet bird by provoking it to peck at her pointed index finger. Such a picturing in the visual art of this painting is matched by comparable visualizations in the verbal art of song and poetry, as for example in Poem 2 of Catullus, where ‘the girl from Lesbos’, Lesbia, is pictured in the act of playfully provoking her pet sparrow to peck at the tip of her index finger. As I argue in Essay 8 of Sappho II, the pet bird pecking at the fingertip of Lesbia in Poem 2 of Catullus may have been modeled on an erotic image that originated—indirectly or perhaps even directly—from a now-lost song of Sappho. Perhaps the pet bird in the image painted by the Meidias Painter is an earlier example of such modeling.

[10§1.] The pictures from two separate vase-paintings that I have shown here can be viewed as an inseparable pair. I have learned this from the work of Alan Shapiro (1993). The pictures are a pair because the two vases on which the Meidias Painter painted his separate paintings were found together inside a tomb at Populonia in Etruria, and, to this day, they stay together on display as inventory items 81947 and 81948 in the Museo Archeologico of Florence. I see here an eschatology of visual art, corresponding to the eschatology of Sappho’s verbal art as posited by Giambattista D’Alessio (2022). Further, just as the vases themselves are an inseparable pair, so too are the overall pictures that are painted on them. In those pictures, as I already noted, the focus is on two mythological figures, the pretty lover-boy Phaon at 81947 and the pretty lover-boy Adonis at 81948, each one of whom is directly linked to Aphrodite, goddess of love, in each one of the two separate paintings.

[10§2.] I took my argument further in Essay 9 of Sappho I. These two pretty lover-boys are not only linked pictorially to the goddess of love. In myth, we can see that there is more to it, since both boys are passionately loved by Aphrodite herself. Even further, both boys are passionately loved by a poetic surrogate of this goddess, who is none other than the persona of Sappho as self-represented in the songs of Sappho.

[10§3.] In both of the two paintings by the Meidias Painter that I have highlighted, we can find a parallel to the poetic role of Sappho as a poetic surrogate for Aphrodite in her love for Phaon and Adonis. In both pictures, Aphrodite is attended by a bevy of beautiful ladies who are evidently her pictorial surrogates-in-love, just as Sappho is Aphrodite’s poetic surrogate-in-love. In terms of my argument, then, the symmetrical positioning of Phaon and Adonis in the two pictures painted by the Meidias Painter seem to be modeled on their comparably symmetrical positioning in the poetics of Sappho.

[10§4.] In earlier work (starting with Nagy 1973), I have argued that Phaon and Adonis as mythological personae are symmetrical love-objects of Sappho as a poetic persona in her songs, just as these two pretty boys are symmetrical love-objects of Aphrodite as a mythological persona in her own right. But there is a difference between Phaon and Adonis in their roles as love-objects: the love of Aphrodite for Phaon, unlike her love for Adonis, is a myth that can be traced back directly to the native poetic traditions of Sappho’s land of Lesbos. In the case of Adonis, by contrast, his links with Aphrodite are far more general—and not at all restricted to myths rooted in Lesbos. Thus, the only certain piece of direct evidence for the reception of Sappho’s songs in these paintings comes from the specific linking of a boy named Phaon with the goddess Aphrodite in one of the two paintings under consideration.

[10§5.] If Sappho’s Phaon is the only piece of direct evidence for the reception of Sappho in these two paintings of the Meidias Painter, the question remains: where, for the painter, is Sappho herself in his paintings? My answer is: even if there is for him no Sappho, there can be personal memories of his having heard Sappho’s songs, whether oftentimes or rarely, and the feelings that such memories bring back with them can best be expressed by idealizing these feelings, which can be deeply personal. And such idealized personal feelings can inspire divine personifications attached to images of beautiful and sensual ladies who attend Aphrodite in the pictures painted by the Meidias Painter. In this regard, I recommend a most relevant book by Alan Shapiro (1993), already mentioned, who offers a wide-ranging analysis of such visual personifications.

[10§6.] The personifications, then, that take shape in the picturing of the beautiful ladies in the paintings of the Meidias Painter can be understood as pictorial surrogates of Aphrodite in her humanized role as goddess-in-love, corresponding to the persona of Sappho as the poetic surrogate of the same goddess in the same role.

[10§7.] To say it more generally, these ladies correspond, as personifications, to the personal feelings of love and sensuality expressed in the songs of Sappho. A most beautiful example is the persona of Pannychis as painted by the Meidias Painter on both of the vases that have survived side-by-side at the museum in Florence. In my talk here, I have no time to show close-ups of her. But this goddess, as I argue in Essay 9 and Essay 10 of Sappho I, personifies the personal experience of a girl who is enjoying the beauty and the pleasure of an all-night party in the company of other girls, as expressed for example in Epigram 55 of Posidippus, highlighted in Essay 3, where girls take turns in singing, all night long, the love songs of Sappho. The lady called Pannychis, whose name means ‘all-night-long’, is figured as a goddess precisely because her personification idealizes a personal experience that proves to be worthy of the goddess Aphrodite herself.

I turn one last time to the songs of Sappho, where the verb pannukhizein, which I propose to translate as ‘have a merry time all night long’, is actually attested (παννυχισδο.[.]α̣.[…] in Fragment 30.3 and [παν]νυχίσ[δ]ην in Fragment 23.13).