Introduction

The Cyrus Cylinder as a foundation deposit

Sacral metonymy

An example of sacral metonymy in the Gilgamesh narrative

An Egyptian parallel

Back to the Cyrus Cylinder

Variations on a theme of copies and models

§35. I argue, then, that the text of the Cyrus Cylinder authenticates itself by claiming to be a sacred archetype, and its archetypal sacredness is guaranteed, ideologically, in three ways:

- 1) by the sacredness of the site in which it is embedded

- 2) by the sacredness of the object itself, and

- 3) by the sacredness of the wording that is written on the surface of the object.

From the standpoint of myth and ritual, the deposited text of the Cyrus Cylinder is so sacred that it should not even be seen, once it is in place, except by the sacred cosmic powers that receive the archetype and are archetypal in their own right. From a practical standpoint, I could add, the act of depositing the text of the Cyrus Cylinder would keep it safe from the depredations of the profane. {345|346}

Authenticating the text and the speaker of the text

Following up

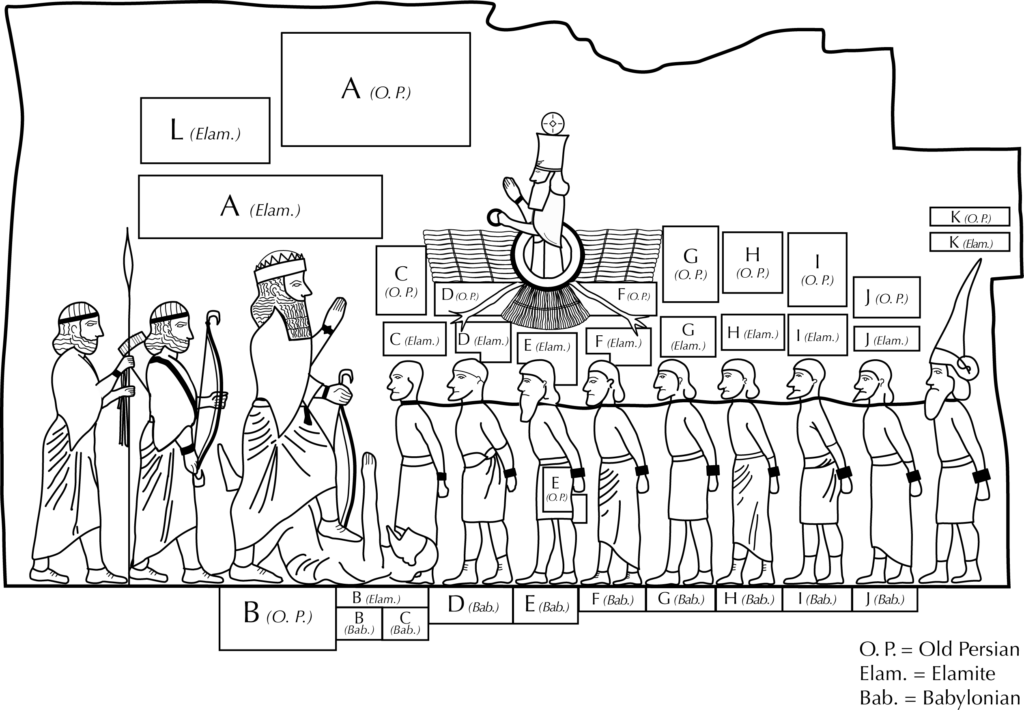

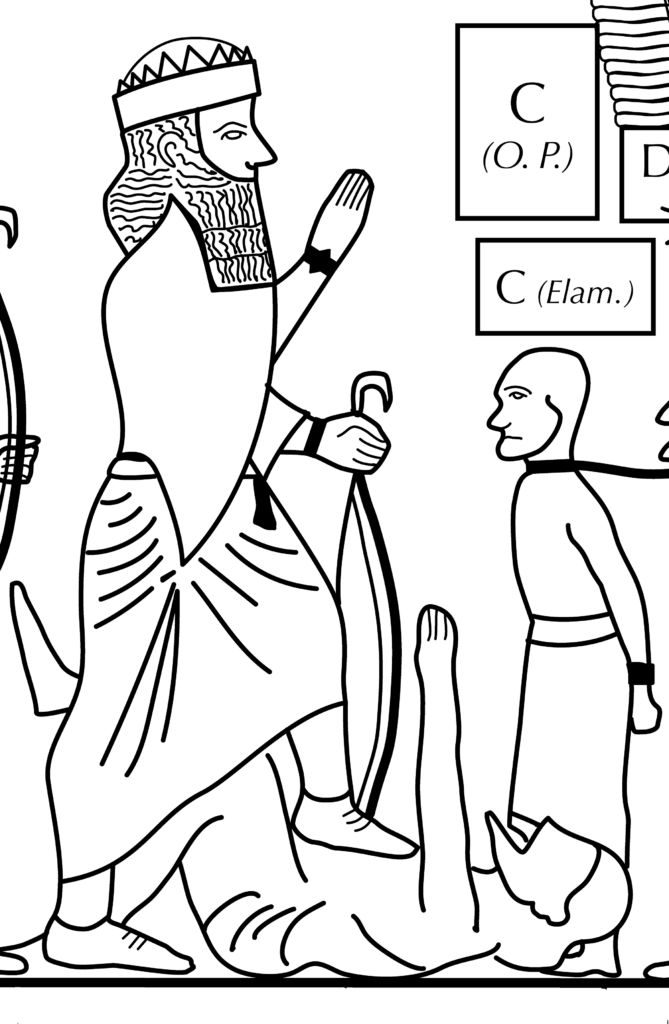

The Bisotun Inscription as an archetype

True kings and false kings

Caring for a king

The concepts of ritual substitution and substitute kingship

§58. The Hittite tradition of ritual substitution derives from earlier Babylonian rituals that marked the festival of the New Year. [37] A related tradition, attested in texts stemming from the neo-Assyrian empire of the first millennium BCE, was the practice of periodically appointing and subsequently killing a substitute king, and the period of such a substitute king’s tenure could be measured astrologically. [38] Especially relevant to this concept of substitute kingship are the descriptions found in the correspondences of the Assyrian kings Esarhaddon (680–669 BCE) and Assurbanipal (668–627 BCE). [39]

§59. Sadly, the attested evidence is meager. Still, even on the basis of what little we have, patterns emerge. Here I adduce again the work of Rahim Shayegan, who summarizes in the following words the patterns that emerge in Mesopotamian rituals of substitute kingship:

Similarities and differences between substitute kingship and counterfeit kingship

§64. Limitations of time and space prevent me from exploring at length here the historical truth behind the variant stories about the death of the man who was declared to be a counterfeit king. Suffice it to say that there are basically two scenarios for viewing the cause of his death:

§66. Weighing the comparative information that can be gleaned from the variant stories about the accession of Darius to kingship by way his killing a rival king, Shayegan offers this useful formulation:

Back to the Cyrus Cylinder

Bibliography

Badawy, A. 1972. A Monumental Gateway for a Temple of King Sety I: An Ancient Model Restored. New York.

Bornstein, G., and R. G. Williams, ed. 1993. Palimpsest: Editorial Theory in the Humanities. Ann Arbor.

Dunham, S. 1986. “Sumerian Words for Foundation.” Revue d’Assyriologie 80:31–64.

Ellis, R. 1968. Foundation Deposits in Ancient Mesopotamia. New Haven.

Finkel, I., ed. 2013. The Cyrus Cylinder. The King of Persia’s Proclamation from Ancient Babylon. London.

George, A. 2003. The Babylonian Gilgamesh Epic: Introduction, Critical Edition, and Cuneiform Texts. 2 vols. Oxford.

Kümmel, H. M. 1967. Ersatzrituale für den hethitischen König. Wiesbaden.

Michalowski, P. 2014. “Biography of a Sentence: Assurbanipal, Nabonidus, and Cyrus.” Extraction and Control: Studies in Honor of Matthew W. Stolper, ed. M. Kozuh, W. F. M. Henkelman, C. E. Jones, and C. Woods, 203–210. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization 68. Chicago.

Nagy, G. 1990. Pindar’s Homer: The Lyric Possession of an Epic Past. Baltimore. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Pindars_Homer.1990.

Nagy, G. 1996. Poetry as Performance: Homer and Beyond. Cambridge. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Poetry_as_Performance.1996.

Nagy, G. 2008. Homer the Classic. Hellenic Studies 36. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Classic.2008. Print edition 2009.

Nagy, G. 2009. Homer the Preclassic. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_Nagy.Homer_the_Preclassic.2009. Print edition 2010, Sather Classical Lectures 67, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Nagy, G. 2013. The Ancient Greek Hero in 24 Hours. Cambridge, MA. http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:hul.ebook:CHS_NagyG.The_Ancient_Greek_Hero_in_24_Hours.2013.

Parpola, S. 1970–1983. Letters from Assyrian Scholars to the Kings Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal. 2 vols. Alter Orient und Altes Testament 5.1–2. Neukirchen-Vluyn.

Ragavan, D. 2010. The Cosmic Imagery of the Temple in Sumerian Literature. PhD diss., Harvard University.

Shayegan, M. R. 2012. Aspects of History and Epic in Ancient Iran: From Gaumāta to Wahnām. Hellenic Studies 52. Cambridge, MA, and Washington, DC.

Skjærvø, P. O. 1985. “Thematic and Linguistic Parallels in the Achaemenian and Sassanian Inscriptions.” Papers in Honour of Professor M. Boyce. Special Issue, Acta Iranica 25:593–603. Leiden.

Skjærvø, P. O. 1999. “Avestan Quotations in Old Persian?” Irano-Judaica 4:1–64. Ed. Sh. Shaked and A. Netzer. Jerusalem.

Skjærvø, P. O. 2003. “Truth and Deception in Ancient Iran.” Ātaš-e Dorun: The Fire Within: Jamshid Soroush Soroushian Commemorative Volume II, ed. C. G. Cereti and F. Vajifdar, 383–434. Bloomington.

Skjærvø, P. O. 2005. “The Achaemenids and the Avesta.” Birth of the Persian Empire, ed. V. S. Curtis and S. Stewart, 52–84. London and New York.

Steinkeller, P. 2004. “A Building Inscription of Sin-iddinam and Other Inscribed Materials from Abu Duwari.” The Anatomy of a Mesopotamian City: Survey and Soundings at Mashkan-shapir, by E. C. Stone and P. Zimansky, with Epigraphy by P. Steinkeller, 135–152. Warsaw, IN.

Traube, L. 1910. Textgeschichte der Regula S. Benedicti. 2nd ed. Munich.

Van Brock, N. 1959. “Substitution rituelle.” Revue Hittite et Asianique 65:117–146.

Van Brock, N. 1961. Recherches sur le vocabulaire médical du grec ancien. Paris.

Wiseman, D. J. 1975. “A Gilgamesh Epic Fragment from Nimrud.” Iraq 37:157–161+163.

Zetzel, J. E. G. 1993. “Religion, Rhetoric, and Editorial Technique: Reconstructing the Classics.” Bornstein and Williams 1993:99–120.

Footnotes

[ back ] 1. My own text here is dedicated to my friend Anthony Snodgrass.

[ back ] 2. My thinking on the term archetype has been enhanced by new perspectives that I derived from lively debates with Shaye Cohen.

[ back ] 3. For a summary of my analysis of the so-called Peisistratean Recension, see Nagy 2010:314–325. For a comparable approach to research on the mythological aetiologies of the Iranian Avesta, I cite Skjærvø 2005.

[ back ] 4. Nagy 1996:184, following Zetzel 1993:103–104, following Traube 1910.

[ back ] 5. Zetzel 1993:103.

[ back ] 6. Zetzel 1993:103.

[ back ] 7. Finkel 2013:64. See in general Ellis 1968. For me the ideal introduction to the concept of foundation deposits is the concise analysis of Steinkeller 2004:135–137.

[ back ] 8. Finkel 2013:64–65.

[ back ] 9. For a reference to this view, see Finkel 2013:26.

[ back ] 10. See Michalowski 2014, who argues persuasively that this reference to Assurbanipal in the text of the Cyrus Cylinder is one of many signs indicating an active adoption of Mesopotamian and even Assyrian precedents on the part of Cyrus.

[ back ] 11. Nagy 2013 4§32, 5§102, 14§16, 14§27, 15§23, 18§15.

[ back ] 12. My citations are based on the edition of George 2003.

[ back ] 13. As Peter Machinist points out to me, the text does not explicitly distinguish between the wall of the city of Uruk and the wall of Eanna, the sanctuary of Ishtar. He goes on to say: “Perhaps the Gilgamesh epic is somehow eliding the wall of the city of Uruk, which is normally understood by scholars to refer to the city-wide wall, of Early Dynastic 1, ca. 3000–2900 BC, with the wall of the Eanna Temple of Ishtar in the Eanna District. I wonder, therefore, whether here in the Gilgamesh Epic the wall of the Eanna Temple of Ishtar is somehow being integrated into the wall of the city of Uruk.” In Nagy 1990:144–145 = 5§16, I have studied the semantics of integration in the historical context of ancient Greek and Latin references to city walls. A case in point is the semantic chain linking the following words in Latin: moenia ‘city wall’ and mūnus ‘communal obligation’ and com-mūnis ‘communal’.

[ back ] 14. George 2003 II 781 notes: “Though Eanna is situated in the middle of Uruk, the topography of the town is such that there are stretches of city wall that take one nearer to the temple area.” Following George, I render giškun4 as ‘stairway’. As for the verb ṣabātu, I interpret it to mean here simply ‘make one’s way’: in this case, to make one’s way up the stairway. I thank Kathryn Slanski for showing me parallel contexts. Also, I thank Piotr Steinkeller for sharing with me a preprinted version of his forthcoming paper “The Employment of Labor on National Building Projects in the Ur III Period,” where he analyzes in some detail the contexts of references to stairways. See also Ragavan 2010:26, 101, 152–153, 229, 235.

[ back ] 15. George 2003(I):526.

[ back ] 16. Chicago Assyrian Dictionary, T (tet) 2006:337–339, with reference to Ellis 1968 and Dunham 1986. I am grateful to Kathryn Slanski for advising me about the uses of this word.

[ back ] 17. See George 2003(I):446 for a critique of literal-minded modern interpretations of this passage: for example, some interpreters are worried about the very idea that the entire Gilgamesh narrative could have been written on a single tablet made of lapis lazuli.

[ back ] 18. Badawy 1972:2, 7. In thinking about this model, I have benefited from conversations with Peter Der Manuelian.

[ back ] 19. Badawy 1972:7.

[ back ] 20. Badawy 1972:2–3, 10.

[ back ] 21. Documentation provided by Badawy 1972:7.

[ back ] 22. Badawy 1972:8.

[ back ] 23. Badawy 1972:10.

[ back ] 24. There is an illuminating schematic illustration provided by Badawy 1972:16.

[ back ] 25. For a comparable example of sacral metonymy, I cite Nagy 2009:501–502 (= 4§116), where I analyze myths centering on the goddess Athena as a moving force in the building of monuments on the Athenian acropolis.

[ back ] 26. Finkel 2013:20.

[ back ] 27. Finkel 2013:23.

[ back ] 28. As I noted at the beginning, I have studied such situations in Nagy 1996.

[ back ] 29. Finkel 2013:4–5.

[ back ] 30. Shayegan 2012:157–159. See also Skjærvø 1985. I acknowledge as well the wealth of information and perspectives in Skjærvø 1999 and 2003; also 2005.

[ back ] 31. Shayegan 2012:157.

[ back ] 32. Shayegan 2012:157. See also Skjærvø 2005:54.

[ back ] 33. I owe this formulation to Peter Machinist.

[ back ] 34. See the translation and commentary of Shayegan 2012:127.

[ back ] 35. I collect examples in Nagy 2013 6§54.

[ back ] 36. Van Brock 1959, 1961; also Nagy 2013 6§§9–23.

[ back ] 37. Kümmel 1967:189, 193–194, 196–197.

[ back ] 38. Nagy 2013 6§14, with reference to Parpola 1983 Excursus pp. xxii–xxxii.

[ back ] 39. Kümmel 1967:169–187.

[ back ] 40. Shayegan 2012:35.

[ back ] 41. Shayegan 2012:35–41.

[ back ] 42. Shayegan 2012:40–41.

[ back ] 43. This formulation derives from an exchange with Peter Machinist.

[ back ] 44. In making this point about the king’s dream as narrated in the passage from Herodotus (3.30.2), I have benefited from observations made viva voce by Samantha Blankenship about this passage.

[ back ] 45. In summarizing this alternative scenario, I have benefited from the incisive observations of Shayegan 2012:xii, 41.

[ back ] 46. On the historicity of both Gaumāta and Bardiya, see Shayegan 2012:27–33.

[ back ] 47. Shayegan 2012:41.