I wrote most of these comments on the Homeric Iliad and Odyssey in the form of serialized postings that were originally published in Classical Inquiries 2016–2017. Selective updatings are folded into a restarted version here in Classical Continuum, starting 2022.12.1. Most of my comments in this overall work are based on observations I made in seven books of mine, indicated in the Bibliography (at the end) by way of these abbreviations: BA, GMP, H24H, HC, HPC, HQ, HR, MoM, PasP, PH. Each one of these books has its own index locorum. My colleague Anita Nikkanen, an Associate Editor for a larger online project, managed to track the sequences of Homeric verses as listed in the indices for six of these books and then summarized my comments on the given verses. Following up on her meticulous work, I rewrote her summaries in the form of the comments that I originally posted in 2016–2017, and these comments of mine, as restarted here as of 2022.12.1, can now be folded into the larger online project that I mentioned a moment ago. That project is called A Homer commentary in progress, abbreviated as AHCIP. The editors of AHCIP, including myself for now, plan to maintain this Homeric commentary as an open-ended project, with each editor contributing further comments. Here is the link to AHCIP: https://homer.oc.newalexandria.info/. And here is a link to a preliminary manifesto that I have written about AHCIP: https://classical-inquiries.chs.harvard.edu/draft-of-a-declaration-by-the-founding-authors-of-a-homer-commentary-in-progress/.

Before I begin the version of my commentary as of now, I list here the names of colleagues who helped me produce this version:

Editors: Keith DeStone, Elizabeth Gipson, Angelia Hanhardt (from 2016 to 2021), Leonard Muellner, Anita Nikkanen, Sloane Wehman

Web producer: Noel Spencer

Consultant for images: Jill Curry Robbins

If you prefer to read a comment in advance, you can jump to:

| Iliad | Rhapsody 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

| Odyssey | Rhapsody 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24 |

Highlighting Legend

| readable even for first-timers |

| readable, but not necessarily the first time around |

| readable, but only by those who might be interested |

| readable mostly for specialists, or in general for those who are very interested in a given topic |

Iliad Rhapsody 1

2016.06.09 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 1. “The Rage of Achilles,” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1757, [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 1. “The Rage of Achilles,” by Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, 1757, [public domain], via Wikimedia Commons.I.01.001–012

I.01.001–002

I.01.001

I.01.001

I.01.002

I.01.002

I.01.002

I.01.003–005

I.01.005

I.01.008–012

I.01.015

I.01.028

I.01.052

I.01.069

I.01.074–083

I.01.075

I.01.086

I.01.091

I.01.096–098

I.01.097

I.01.110

I.01.122

I.01.153

I.01.155

I.01.159

I.01.177

I.01.188

I.01.197

I.01.207

I.01.225

I.01.231

I.01.233–246

I.01.233–237

I.01.244

I.01.247

I.01.282

I.01.291

I.01.320–348

I.01.321

I.01.335

I.01.337

I.01.341

I.01.345

I.01.350–359

I.01.362

I.01.365–392

I.01.396–406

I.01.403–404

I.01.407–412

I.01.412

I.01.416

I.01.418

I.01.423–425

I.01.454

I.01.456

I.01.463

I.01.463

From a purely linguistic point of view, an ‘Aeolian’ was whoever spoke a dialect known as Aeolic, which along with Ionic and Doric was a major dialectal grouping of the Greek language. From an anthropological point of view, however, there is more to it: as we see from such sources as Herodotus in the fifth century BCE, an Aioleús ‘Aeolian’ was whoever belonged to a social and cultural grouping of Greeks who distinguished themselves in their rituals and myths from other social and cultural groupings. Thus the Aioleîs ‘Aeolians’ were socially and culturally distinct from, say, the Iōnes ‘Ionians’, as we see for example from the remarks of Herodotus 1.149 about a twelve-city confederation of Aioleîs ‘Aeolians’ located on the mainland of northern Asia Minor, which rivaled a corresponding twelve-city confederation of Iōnes ‘Ionians’ located on the mainland of central Asia Minor. (See under Aeolian Dodecapolis and Ionian Dodecapolis in the Inventory of terms and names.) And these differentiated social groupings of Aioleîs ‘Aeolians’ and Iōnes ‘Ionians’—as also Dōrieîs ‘Dorians’—corresponded neatly with the linguistic groupings of the dialects spoken in Asia Minor and in its outlying islands:

I.01.468

I.01.473

I.01.477

I.01.503–510

I.01.509

I.01.524–530

I.01.528–530

I.01.558–559

I.01.602

I.01.603–604

Iliad Rhapsody 2

2016.07.01 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 2. Inscription on the reverse side of the coin: ΘΗΒΑΙΩΝ. Pictured: the Greek hero Protesilaos, the first Achaean to step on Trojan soil and, according to the myth, the first to die in the Trojan War. The myth is retold in Iliad 2.695–709.

Figure 2. Inscription on the reverse side of the coin: ΘΗΒΑΙΩΝ. Pictured: the Greek hero Protesilaos, the first Achaean to step on Trojan soil and, according to the myth, the first to die in the Trojan War. The myth is retold in Iliad 2.695–709.I.02.001–006

I.02.007–015

I.02.026

I.02.029–030

I.02.036–040

I.02.041

I.02.046

I.02.063

I.02.082

I.02.086

I.02.094

I.02.100–108

I.02.101

I.02.108

I.02.110

I.02.119–130

I.02.186

I.02.212

I.02.214

I.02.216

I.02.217–219

I.02.221

I.02.222

I.02.224

I.02.225–242

I.02.235

I.02.241–242

I.02.243

I.02.245

I.02.246–264

I.02.246

I.02.247

I.02.248–249

I.02.251

I.02.255

I.02.256

I.02.265–268

I.02.268

I.02.269–270

I.02.275

I.02.277

I.02.299–332

I.02.299–310

I.02.308

I.02.318

I.02.319

I.02.325

I.02.330

I.02.401

I.02.402–429

I.02.402–429

I.02.408–409

I.02.408

Epitome from Nagy 2015§104:

I.02.431

I.02.484–487

I.02.484

I.02.486

I.02.488–493

subject heading(s): re-experiencing of performance

I.02.492

I.02.493

I.02.540

I.02.546–552

subject heading(s): Erekhtheus; Athena and Athens

I.02.546

I.02.547–548

I.02.548

I.02.553–554

I.02.557–568

I.02.557–558

I.02.577

I.02.580

I.02.594–600

I.02.637

I.02.653–670

I.02.655–656

I.02.658

I.02.663

I.02.666

I.02.668

I.02.681–694

I.02.689–694

I.02.689–694

I.02.695–709

I.02.704

I.02.745

I.02.760–770

I.02.761

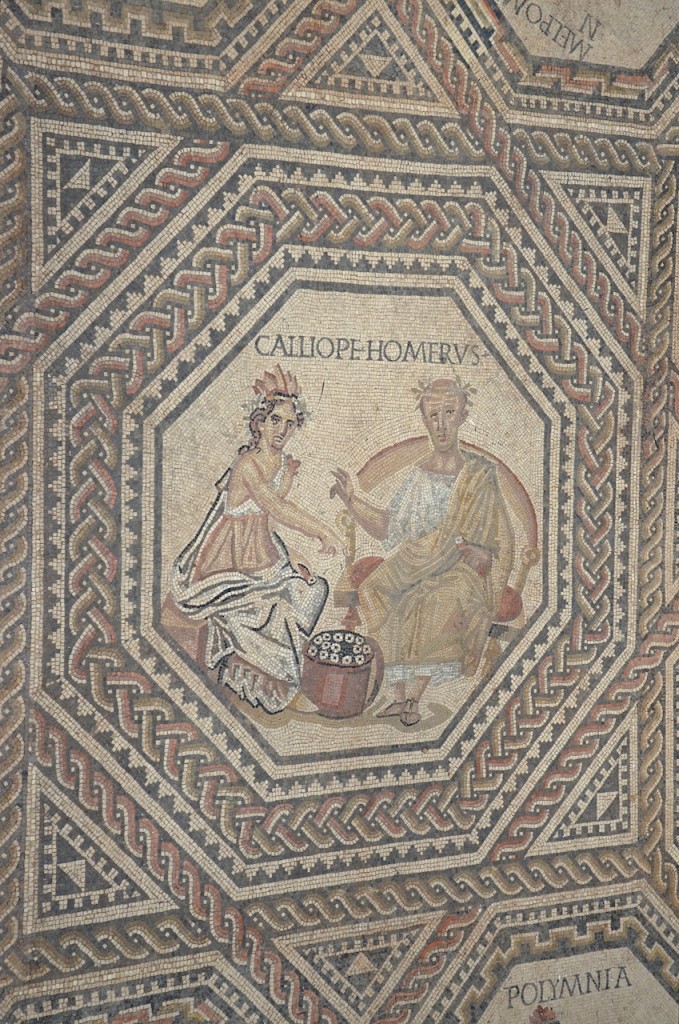

“The Muse Calliope” (about 1730). Charles-Antoine Coypel (1694–1752). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“The Muse Calliope” (about 1730). Charles-Antoine Coypel (1694–1752). Image via Wikimedia Commons. Central medallion of the Vichten mosaic (about 240 CE). National Museum of History and Art, Luxembourg. Image via Flickr, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.

Central medallion of the Vichten mosaic (about 240 CE). National Museum of History and Art, Luxembourg. Image via Flickr, under a CC BY-SA 2.0 license.I.02.761

Unlike what we see at I.02.484, I.11.218, I.14.508, I.16.112, where the Muses are invoked as plural goddesses, the Muse here at I.02.761 is invoked as a singular goddess. And the Muse is of course singular also at the beginning of the Iliad, I.01.001, and at the beginning of the Odyssey, O.01.001. There are also two other cases where a singular Muse is invoked:

“Calliope” (1869). Giuseppe Fagnani (1819–1873). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“Calliope” (1869). Giuseppe Fagnani (1819–1873). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The medium for the reading of Homer here is imagined as a codex, not as a scroll: compounding of anachronisms.

“Calliope, Muse of Epic Poetry” (1620). Giovanni Baglione (1566–1643). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

“Calliope, Muse of Epic Poetry” (1620). Giovanni Baglione (1566–1643). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.02.811–815

I.02.829

I.02.831–832

I.02.835

I.02.842

I.02.867–869

Iliad Rhapsody 3

2016.07.07 / enhanced 2018.08.16

Figure 3. Menelaos pulling Paris by the helmet. Detail of Roman sarcophagus of Aurelia Botania Demetria (2nd c. CE); Antalya Archaeological Museum. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 3. Menelaos pulling Paris by the helmet. Detail of Roman sarcophagus of Aurelia Botania Demetria (2nd c. CE); Antalya Archaeological Museum. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.03.038

I.03.059

I.03.100

I.03.125–128

I.03.126

I.03.147

I.03.164

I.03.237

I.03.242

I.03.284

I.03.374

Iliad Rhapsody 4

2016.07.21 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 4. The healer Makhaon attends to the wounded Menelaos. Engraving by Francesco Nenci for an edition of the Iliad published in 1838.

Figure 4. The healer Makhaon attends to the wounded Menelaos. Engraving by Francesco Nenci for an edition of the Iliad published in 1838.I.04.048

I.04.110

I.04.118–121

I.04.128

I.04.178-179

I.04.183

I.04.196

I.04.197

I.04.227

I.04.241

I.04.242

I.04.313–314

I.04.327–328

I.04.368–410

I.04.386

I.04.389

I.04.513

Iliad Rhapsody 5

2016.07.28 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 5a. “Aeneas and Diomedes.” Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5a. “Aeneas and Diomedes.” Wenceslaus Hollar (Bohemian, 1607–1677). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.05.048

I.05.059–064

I.05.059–061

I.05.063

I.05.077–078

I.05.077–078

I.05.083

I.05.103

I.05.173

I.05.231

I.05.263–273

I.05.269

I.05.296

I.05.312

I.05.369

I.05.370–371

I.05.395–404

I.05.401

I.05.406–415

I.05.430

I.05.432–444

Figure 5b. “The Combat of Diomedes” (1776). Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 5b. “The Combat of Diomedes” (1776). Jacques-Louis David (French, 1748–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.05.438

I.05.440–442

I.05.441–442

I.05.441

In the case of metaphors, Aristotle himself actually uses the word homoio– in his own definition of metaphor, Poetics 1459a5–8:

I.05.459

I.05.473–474

I.05.500

I.05.541

I.05.571

I.05.580

I.05.638

I.05.639

I.05.646

I.05.669

I.05.696–698

I.05.710

I.05.722

I.05.733–747

I.05.734–735

I.05.795

I.05.839

I.05.843

I.05.891

I.05.899

Iliad Rhapsody 6

2016.08.04 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 6. Apulian red-figure column-crater (ca. 370–360 BCE) depicting an intimate family scene: Hector removes his helmet as he says his final farewell to his wife Andromache and to their child Astyanax. Public domain image by Jastrow via Wikimieda Commons.

Figure 6. Apulian red-figure column-crater (ca. 370–360 BCE) depicting an intimate family scene: Hector removes his helmet as he says his final farewell to his wife Andromache and to their child Astyanax. Public domain image by Jastrow via Wikimieda Commons.I.06.018

I.06.053

I.06.067

I.06.090–093

I.06.119–149

I.06.271–273

I.06.209

I.06.211

I.06.286–311

I.06.286–296

Hecuba goes ahead and does what she has been told to do, which is, to offer a peplos ‘robe’ for Athena as the goddess of the citadel of Troy. The repetition of ritual wording in the sequence of three passages—from I.06.090–093 to I.06.271–273 to I.06.286–296—will culminate in a master plan, as it were, for performing the ritual of presenting the peplos ‘robe’ to Athena as goddess of Troy. What has just been described as a “repetition,” however, needs to be explained further (HPC 268):

I.06.289–292

I.06.294

I.06.297–310

I.06.325

I.06.333

I.06.402–403

I.06.407–439

I.06.407–439

I.06.447–464

I.06.466–470

I.06.484

I.06.494–496

Iliad Rhapsody 7

2016.08.12 / enhanced 2018.09.08

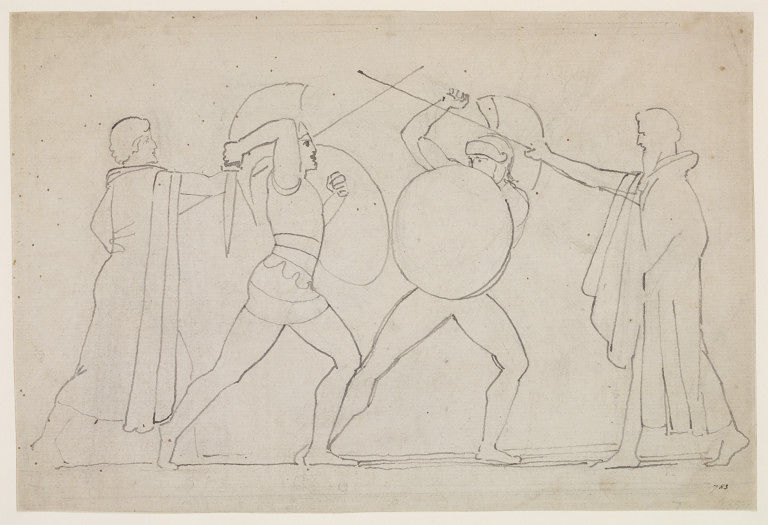

Figure 7. Hector and Ajax separated by heralds, pen and ink drawing by John Flaxman, 1790’s. Image via Victoria and Albert Museum.

Figure 7. Hector and Ajax separated by heralds, pen and ink drawing by John Flaxman, 1790’s. Image via Victoria and Albert Museum.I.07.015–017

I.07.015–017

I.07.017–061

I.07.021

I.07.063–064

I.07.067–091

I.07.084–086

I.07.089–090

I.07.090

I.07.092–169

I.07.095

I.07.122

I.07.123–161

I.07.132–157

I.07.147

I.07.149

I.07.161

I.07.177–180

I.07.197–198

I.07.203

I.07.228

I.07.288–289

I.07.298

I.07.319–322

I.07.324

I.07.336–343

I.07.382

I.07.421–423

I.07.433–465

Iliad Rhapsody 8

2016.08.18 / enhanced 2018.09.08

Figure 8. “Hera, Athena, and Iris in the Trojan War,” Jacques Réattu (1760–1833). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 8. “Hera, Athena, and Iris in the Trojan War,” Jacques Réattu (1760–1833). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.08.002

I.08.002

I.08.066–077

I.08.078–117

I.08.078–117

I.08.079

I.08.104

I.08.107

I.08.113–114

I.08.119

I.08.123

I.08.130–171

I.08.170–171

I.08.175–176

I.08.180–183

I.08.185

I.08.215

I.08.220–227

I.08.228–235

I.08.315

I.08.339

I.08.363

I.08.367

I.08.379–380

I.08.485–486

I.08.526–541

l.08.526

I.08.538–541

Iliad Rhapsody 9

2016.08.26 / enhanced 2018.09.08

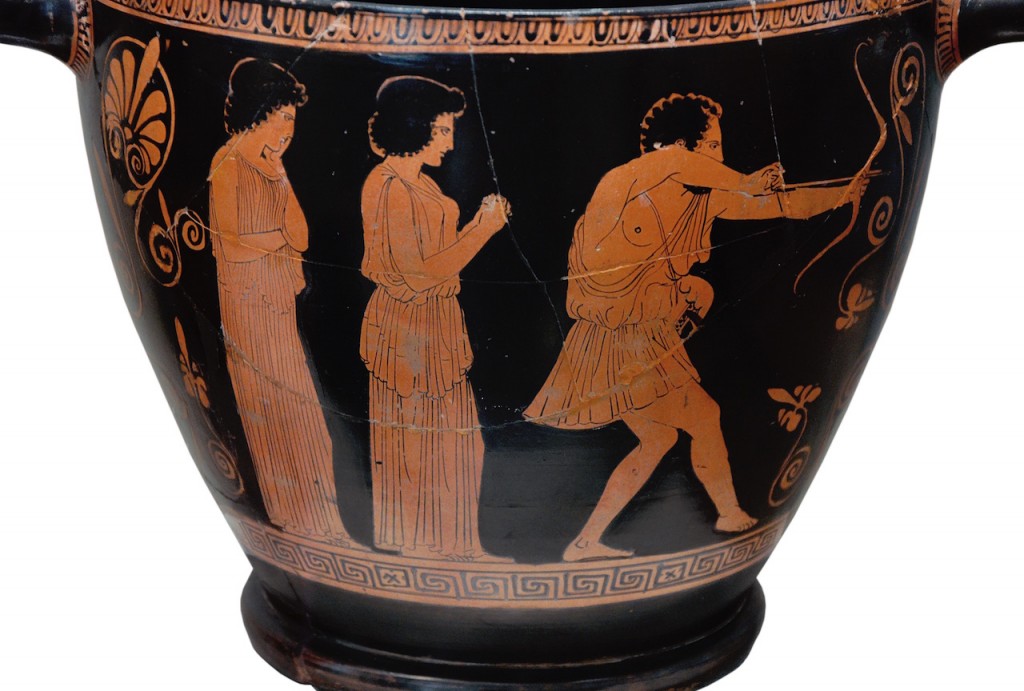

Figure 9. The embassy to Achilles, featuring Phoenix and Odysseus in front of Achilles. Attic red-figure hydra, circa 480 BCE. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 9. The embassy to Achilles, featuring Phoenix and Odysseus in front of Achilles. Attic red-figure hydra, circa 480 BCE. Public domain image via Wikimedia Commons.I.09.001–003

I.09.002

I.09.003

I.09.004–008

I.09.004

I.09.008–009

I.09.057–058

I.09.076–077

I.09.097–099

I.09.104–108

I.09.115–120

I.09.120–161

I.09.128–131 / I.09.270–272

I.09.128–131 / I.09.270–272

I.09.130

I.09.158–161

I.09.167–170

I.09.179–181

I.09.182–198

I.09.185–191

I.09.193–198

I.09.223

I.09.225–306

I.09.225–228

I.09.229

I.09.236

I.09.241–243

I.09.249–250

I.09.260

I.09.260–299

I.09.270–272

I.09.307–430

I.09.308–311

I.09.312–313

I.09.314–429

I.09.328–333

I.09.328–333

There are ten points in this anchor comment, epitomized mostly from HPC 131–146:

I.09.340–343

I.09.346–352

I.09.359–363

I.09.360

I.09.404–405

I.09.410–416

I.09.413

I.09.421–422

I.09.434–605

I.09.435–436

I.09.502–512

I.09.522

I.09.524–599

I.09.561–564

I.09.590–594

I.09.602

I.09.606–619

I.09.617–618

I.09.624–642

I.09.628–638

I.09.642

I.09.643–655

I.09.650–653

I.09.656–657

I.09.664–668

I.09.674

Iliad Rhapsody 10

2016.09.14 / enhanced 2018.09.11

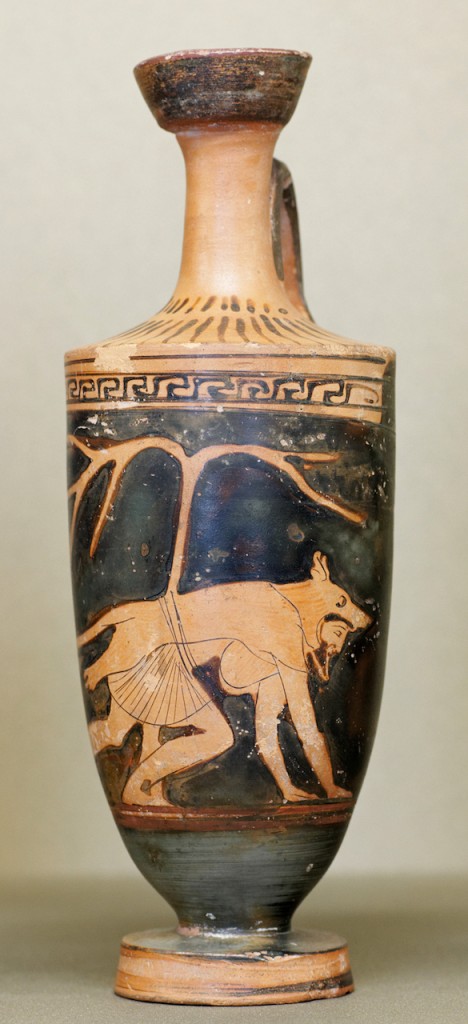

Figure 10. Dolon. Detail from an Attic red-figure lekythos (460 BCE). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 10. Dolon. Detail from an Attic red-figure lekythos (460 BCE). Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.10.000

I.10.032–033

I.10.043–052

I.10.212–213

I.10.213

I.10.224–226

I.10.227–232

I.10.228

I.10.233–240

I.10.241–247

I.10.249–253

I.10.316

I.10.329

I.10.415

I.10.437

I.10.437

I.10.482

Iliad Rhapsody 11

2016.09.22 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 11. Nestor and his sons sacrifice to Poseidon. Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 400–380 BCE. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 11. Nestor and his sons sacrifice to Poseidon. Attic red-figure calyx-krater, ca. 400–380 BCE. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons, via Wikimedia Commons.I.11.001–002

I.11.005–016

I.11.032–040

I.11.041

I.11.058

I.11.078–079

I.11.104–112

I.11.200

I.11.218–231

I.11.218

I.11.227

I.11.288

I.11.295

I.11.297-298

I.11.297

I.11.317–319

I.11.322

I.11.347

I.11.488

I.11.497–500

I.11.506

I.11.508

I.11.564

I.11.599-600

I.11.604

I.11.620

I.11.624–627

I.11.624–627

I.11.627

I.11.664–667

I.11.668

I.11.670

I.11.699–702

I.11.671-761

I.11.690

I.11.735

I.11.784

I.11.787

I.11.806–808

I.11.818

I.11.832

I.11.843

Iliad Rhapsody 12

2016.09.28 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 12. “Siege of the Greek Camp.” Crispijn van de Passe (I) (1613). Public domain image, via Rijks Museum.

Figure 12. “Siege of the Greek Camp.” Crispijn van de Passe (I) (1613). Public domain image, via Rijks Museum.I.12.002–033

I.12.015

I.12.018

I.12.023

I.12.070

I.12.076

I.12.090

I.12.111

I.12.118–123

I.12.130

I.12.159

I.12.188

I.12.198

I.12.228

I.12.235–236

I.12.252

I.12.255–257

I.12.270

I.12.310–321

I.12.319

I.12.322–328

I.12.331–377

I.12.335–336

I.12.387–391

I.12.400

I.12.436–441

Iliad Rhapsody 13

2016.10.13 / enhanced 2018.09.11

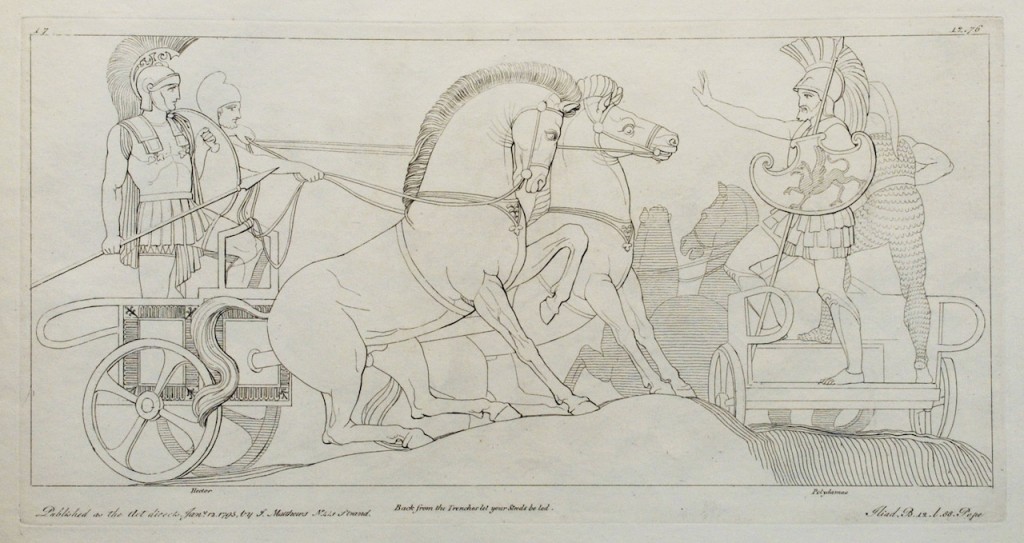

Figure 13. Hector and Polydamas. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 13. Hector and Polydamas. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.13.023–031

I.13.046–047

I.13.054

I.13.066

I.13.084

I.13.111–113

I.13.197

I.13.201

I.13.202–204

I.13.216–218

I.13.227

I.13.242–244

I.13.244

I.13.246

I.13.313–314

I.13.331

I.13.347

I.13.386

I.13.402–423

I.13.435

I.13.444

I.13.459–461

I.13.600

I.13.628–629

I.13.631–639

I.13.659

I.13.681

I.13.685

I.13.688

I.13.689–691

I.13.700

I.13.726–735

I.13.737–739

I.13.795–799

I.13.802

I.13.825–829

I.13.831–832

Iliad Rhapsody 14

2016.10.19 / enhanced 2018.09.11

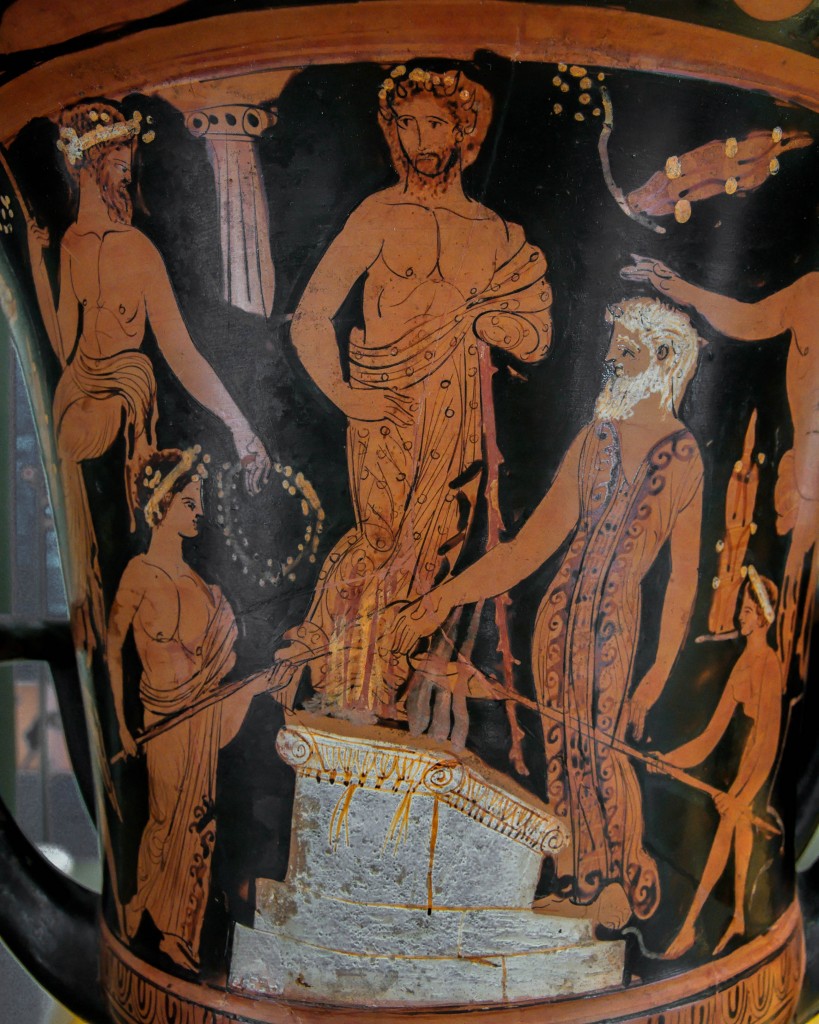

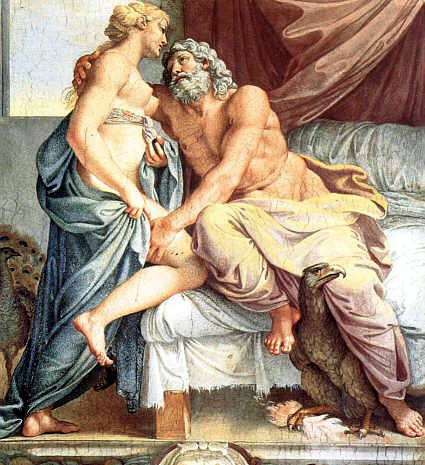

Figure 14. Juno and Jupiter. Detail from “Loves of the Gods,” fresco by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609). Annibale Carracci [Public domain], Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 14. Juno and Jupiter. Detail from “Loves of the Gods,” fresco by Annibale Carracci (1560–1609). Annibale Carracci [Public domain], Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.14.027–036

I.14.070

I.14.187

I.14.200–210

I.14.201

I.14.238–240

I.14.245–246–246a

Our source for this set of verses, I.14.245–246–246a, is Plutarch On the face in the moon 938d, whose narrative provides a context for including verse 246a in such a set. Without the testimony of Plutarch, we would not know about this verse, since it does not survive in the medieval manuscript tradition. But it had survived, as we know from Plutarch, in the text of the Homeric Iliad as edited by Crates of Mallos, Director of the Library of Pergamon (see under Crates in the Inventory of terms and names). In that text, verse 246 of Iliad 14 was followed by another verse, labeled as 246a in modern editions:

I.14.246a ἀνδράσιν ἠδὲ θεοῖς, πλείστην <τ᾿> ἐπὶ γαῖαν ἵησιν

Taken together, these verses can be translated this way:

I.14.246a men and gods, and he flows over the Earth in all her fullness.

I.14.270–280

I.14.282–293

I.14.301–302

I.14.436

I.14.483

I.14.508

Iliad Rhapsody 15

2016.10.27 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 15. Ajax defending the ships of the Greeks. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 15. Ajax defending the ships of the Greeks. After a drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.15.037–038

I.15.059–060

I.15.056–077

I.15.064–071

I.15.069–071

I.15.189

I.15.233

I.15.262

I.15.309–310

I.15.383

I.15.385

I.15.401

I.15.405–407

I.15.414–421

I.15.428

I.15.431

I.15.494–499

I.15.564

I.15.585

I.15.592–602

I.15.640

I.15.696–746

I.15.704-746

I.15.733

Iliad Rhapsody 16

2016.11.09 / enhanced 2018.09.11

Figure 16. A chariot driver and a chariot fighter in a biga (two-horses chariot). Terracotta, Late Helladic IIIA–IIIB (ca. 1400–1200 BCE). Louvre Museum, CA 2959. Credit line: Purchase, 1934. Image Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2009-06-28 [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 16. A chariot driver and a chariot fighter in a biga (two-horses chariot). Terracotta, Late Helladic IIIA–IIIB (ca. 1400–1200 BCE). Louvre Museum, CA 2959. Credit line: Purchase, 1934. Image Marie-Lan Nguyen (User:Jastrow), 2009-06-28 [CC BY 2.5], via Wikimedia Commons.I.16.021

I.16.022

I.16.032

I.16.052

I.16.055

I.16.057

I.16.075

I.16.080

I.16.087–096

I.16.097–100

I.16.112

I.16.113

I.16.119–121

I.16.122–124

I.16.140–144

I.16.149

I.16.150–151

I.16.165

I.16.189

I.16.213

I.16.235

I.16.237

I.16.240–248

I.16.244

I.16.255-256

I.16.271–272

I.16.272

I.16.273–274

I.16.279

I.16.282

I.16.286

I.16.293/301

I.16.294–298

I.16.301

I.16.362

I.16.364–366

I.16.383–393

I.16.437

I.16.440–457

I.16.454–455

I.16.455

I.16.456–457

I.16.464

I.16.514

I.16.548–553

I.16.605

I.16.653

I.16.670

I.16.671–673

I.16.673

I.16.674–675

I.16.680

I.16.682

I.16.683

I.16.685–687

I.16.705–711

I.16.722–723

I.16.767

I.16.784

I.16.786–804

I.16.787

I.16.804–806

I.16.815

I.16.844–845

I.16.856

I.16.865

Iliad Rhapsody 17

2016.11.18 / enhanced 2018.09.20

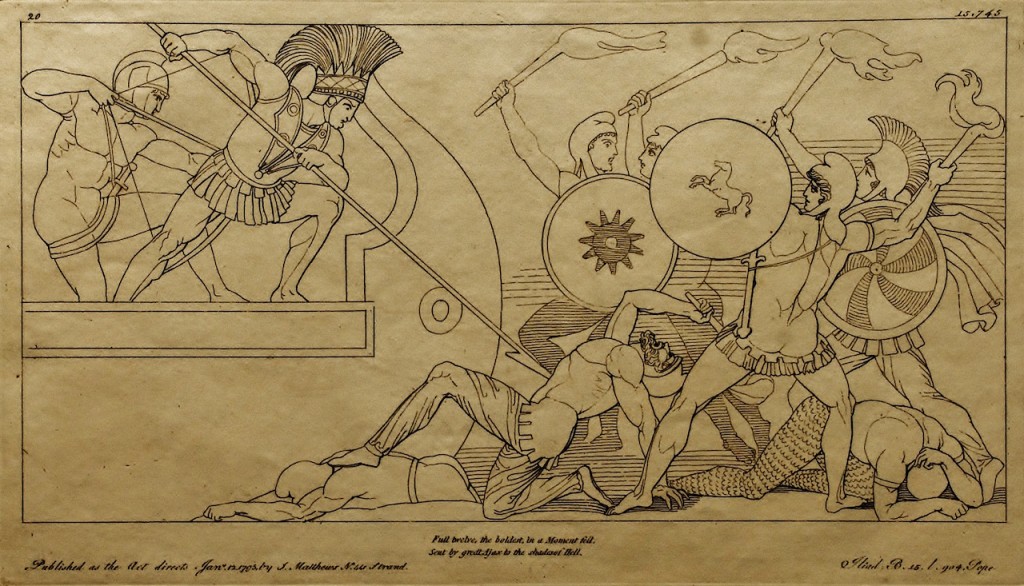

Figure 17. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Photographed/scanned by H.-P.Haack (Antiquariat Dr. Haack Leipzig) [CC BY 3.0 or Public domain]. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 17. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Photographed/scanned by H.-P.Haack (Antiquariat Dr. Haack Leipzig) [CC BY 3.0 or Public domain]. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.17.050–060

I.17.051–052

I.17.053–060

I.17.072

I.17.088

I.17.098–101

I.17.164

I.17.165

I.17.176–178

I.17.187

I.17.194–214

I.17.194–197

I.17.194

I.17.211

I.17.213-214

I.17.271

I.17.279–280

I.17.319–322

I.17.331–332

I.17.388

I.17.411

I.17.432

I.17.456

I.17.474–483

I.17.547–549

I.17.565

I.17.627

I.17.655

I.17.685–690

I.17.736–741

Iliad Rhapsody 18

2016.11.25 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 18. “The Shield of Achilles.” Illustration originally published in The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, September 22, 1832.

Figure 18. “The Shield of Achilles.” Illustration originally published in The Penny Magazine of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, September 22, 1832.I.18.009–011

I.18.015–073

I.18.051–060

I.18.070–071

I.18.073

I.18.074–077

I.18.076

I.18.080–082

I.18.082–085

I.18.095–099

I.18.102–103

I.18.121

I.18.150

I.18.152

I.18.205–206

I.18.214

I.18.225–226

I.18.242

I.18.243–314

I.18.354–356

The particle de (δέ) of I.18.356 is syntactically correlated with the particle men (μέν) in a preceding verse, I.18.354. But a rhapsode (rhapsōidos) could begin his performance with the de-clause, thus “stranding,” as it were, the preceding men-clause. Here is an example, with reference to the performance of a rhapsode in the Ptolemaic era of Alexandria:

I.18.369–371

I.18.399

I.18.464–466

I.18.468–613

I.18.478–609

I.18.479–480

I.18.483–608

I.18.482–489

I.18.487–489

I.18.490–491

I.18.491–508

I.18.492

I.18.497–508

I.18.499

I.18.509–515

I.18.515–519

I.18.519

I.18.567–572

I.18.587–589

I.18.590–606

subject heading(s): Homer’s “signature”; khoros ‘place for singing / dancing’, group of singers /dancers’; Daedalus; Hephaistos; Ariadne

I.18.590

I.18.603–604–(605–)606

Iliad Rhapsody 19

2016.12.01 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 19. Herakles at the tree of the Hesperides, holding three of the golden apples in his left hand. Behind him is the apple tree with the guardian serpent clinging around it. Bronze, 104.5cm (Roman, 1st century C.E.). Image via The British Museum.

Figure 19. Herakles at the tree of the Hesperides, holding three of the golden apples in his left hand. Behind him is the apple tree with the guardian serpent clinging around it. Bronze, 104.5cm (Roman, 1st century C.E.). Image via The British Museum.I.19.001–002

I.19.003–017

I.19.015–017

I.19.031

I.19.044

I.19.047

I.19.056–073

I.19.058–060

I.19.074-075

I.19.076–138

I.19.076–082

I.19.078

I.19.083

I.19.084–085

I.19.085–086

I.19.086–088

I.19.088

I.19.091

I.19.095–133

I.19.098

I.19.105

I.19.111

I.19.134–138

I.19.143

I.19.155

I.19.179–180

I.19.186

I.19.199–214

I.19.216–237

I.19.216

I.19.224

I.19.245–246

I.19.268–281

I.19.268–275

I.19.275

I.19.282–302

The wording of Briseis in addressing the corpse of Patroklos is not just a speech expressing her sorrows: morphologically, it is a song of lament. In what follows, I make ten points about this lament:

I.19.284

I.19.302

I.19.303–308/312–313/314–321

I.19.322–323

I.19.314–338

I.19.327

I.19.329–330, 337

I.19.368–391

I.19.373–380

I.19.404–418

Iliad Rhapsody 20

2016.12.09 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 20. “Venus preventing her son Aeneas from killing Helen of Troy,” Luca Ferrari, circa 1650. Luca Ferrari [Public domain], image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 20. “Venus preventing her son Aeneas from killing Helen of Troy,” Luca Ferrari, circa 1650. Luca Ferrari [Public domain], image via Wikimedia Commons.I.20.001–074

I.20.089–102

I.20.178–198

I.20.187–194

I.20.189

I.20.200–258

I.20.209

I.20.209

So, Aeneas in the Homeric Iliad can boast about the eternal genes that make him the ideal ancestor of any dynasty that claims to be descended from him. And that is how, from the hindsight of world history, Rome could claim its destiny as the Eternal City. I have already noted that Strabo (13.1.53 C608), after listing various dynasties in the past that had been vying with each other for possession of Aeneas as their ancestor, concludes by acknowledging Rome as the world power that ultimately won out in claiming Aeneas as its founder. And Virgil’s Aeneid can go down in history as a most powerful statement of such a claim. But what about the era when the Homeric Iliad took shape? Does this epic make a claim that is comparable to what we see in the Aeneid of Virgil? Such questions need to be consolidated and asked retrospectively, not just prospectively, since the historically earlier cases where dynasties claimed descent from Aeneas are not nearly as well attested as is the case of Rome. So, the consolidated question is this: from the standpoint of the Iliad as we have it, was there any existing political power that could have claimed ownership, as it were, of Aeneas? The answer is simple: there did exist some grouping of Ionians that had such power, and, for them, Aeneas was an Ionian. But the details, as we will see in what follows, are complicated. And, to complicate things further, there were two phases of Ionian ownership, which I summarize here in the form of two points to be made from the start.

This version of the Aeneas story matches not only the plot of the epic Iliou Persis. It matches also the local mythology of the city of Scepsis, located in the region of Mount Ida. As we learn from Strabo (13.1.53 C607), Demetrius of Scepsis claimed explicitly that the basileion ‘royal palace’ of Aeneas was in the city of Scepsis. The idea of a royal city founded by Aeneas in the region of Mount Ida reflects the political interests of Ionians in general, not only of Scepsis in particular. To make this point, I start by focusing on two details reported by Demetrius of Scepsis by way of Strabo (13.1.52 C607):

I.20.213–214

I.20.215–219

I.20.230–241

I.20.238

I.20.241

I.20.244–256

I.20.248–250

I.20.290–352

I.20.302–308

The prophecy that is made by the god Poseidon here about the descendants of Aeneas as heirs to eternal rule over the Trojans—but not in Troy—is a basic theme that pervades Ionian epic traditions. The identity of Aeneas as an Ionian depends ultimately on the idea that he must be relocated from ancient Troy, since that city simply must be destroyed completely. There are four points that now need to be made about this idea:

I.20.302–308

The four points that have just been made about Aeneas the Ionian need to be juxtaposed with twelve points that now need to be made about Aeneas the Aeolian, as featured in rival traditions. [These twelve points are epitomized from HPC 197–201.]

Point 2. In terms of the Aeolian claims, according to which Troy was not completely abandoned after its capture by the Achaeans, there was not only a surviving population that stayed in old Ilion but also a dynasty that ruled over such a population. There are traces of a traditional narrative about such a dynasty in the Trōïka of Hellanicus of Lesbos (FGH 4 F 31), as reported by Dionysius of Halicarnassus (Roman Antiquities 1.45.4–1.48.1): according to this narrative, Aeneas himself was at least indirectly involved in such a dynasty. In this role, Aeneas would have been not an Ionian but an Aeolian. Here is a summary of what Hellanicus says:

I.20.350

I.20.403–405

I.20.487

Iliad Rhapsody 21

2016.12.15 / enhanced 2018.09.20

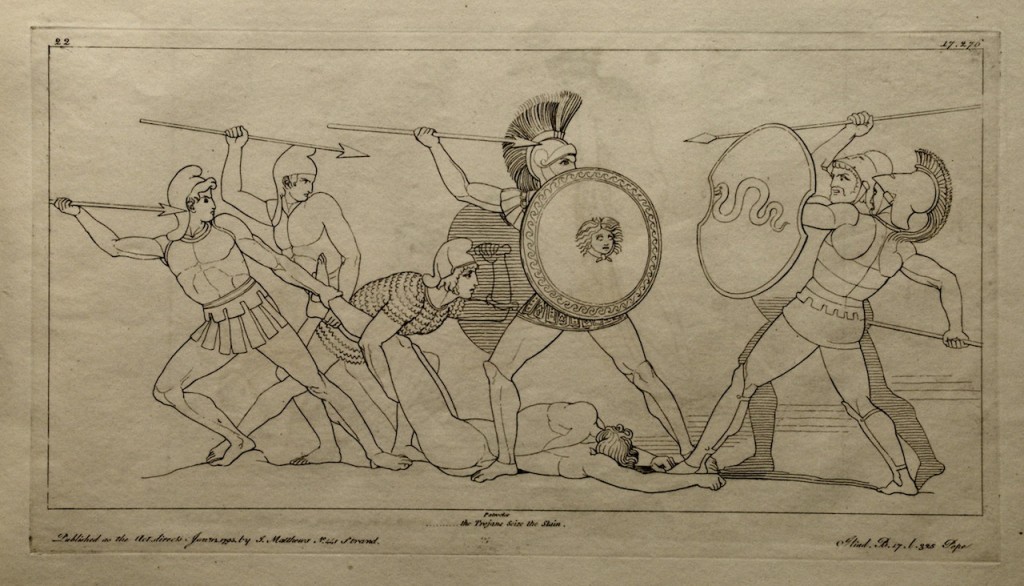

Figure 21. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 21. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.21.001–021

I.21.134–135

I.21.184–199

I.21.194–197

I.21.200–327

I.21.328–384

I.21.385–514

Iliad Rhapsody 22

2016.12.24 / enhanced 2018.09.20

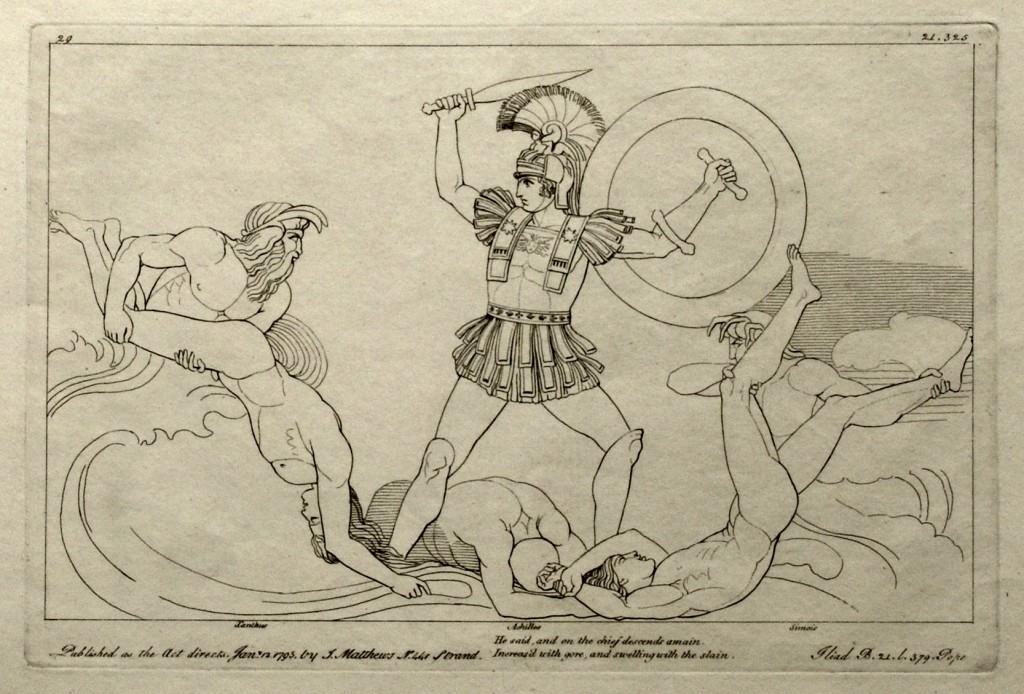

Figure 22. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 22. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.22.110

I.22.122–130

I.22.297–305

I.22.304

I.22.335–354

I.22.346–348

I.22.368–375

I.22.395–405

I.22.437–475

I.22.440–441

I.22.441

I.22.444

I.22.460–474

I.22.476–515

1.22.483

I.22.500

I.22.506–507

I.22.514

I.22.515

Iliad Rhapsody 23

2016.12.30 / enhanced 2018.09.20

Figure 23. Achilles dragging the body of Hector. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 23. Achilles dragging the body of Hector. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.23.001–064

While the Trojans are mourning Hector in Troy, I.23.001, Achilles and his fellow Achaeans have all returned to the ships beached at the Hellespont, I.23.001–002, and the hero now calls on the Myrmidons, whose leader he is, to perform special funerary rituals in mourning for Patroklos. The Myrmidon warriors are to mourn Patroklos while driving their chariots around his dead body three times, I.23.007–009, I.23.013–014, after which they are to unharness the chariots and join in a funeral feast arranged by Achilles. The ritual act of mourning while driving, as performed by the Myrmidons, is described overall as a góos ‘lament’, I.23.010, for which Achilles himself is the principal performer, as signaled by the verb arkhein ‘lead off [in performing]’, I.23.012. The words of his lead-off lament are quoted at I.23.019–023. In this lament, Achilles addresses the dead Patroklos and repeats to him at I.23.20–23 the two deeds that he had promised at I.18.334–337 to perform before the funeral could take place. First, Achilles had promised to bring back, together with the dead body of Hector, the armor that Hector had stripped from the dead body of Patroklos, and now he reiterates that promise, adding two ghastly details about the dead body of Hector: he has dragged the corpse behind his chariot and intends to feed it to the dogs, I.23.021. And, second, Achilles had also promised to slaughter twelve captive Trojan youths on the funeral pyre of Patroklos and then to cremate their bodies together with the body of Patroklos himself, I.23.022–23. After repeating these promises to Patroklos within the wording of his quoted lament, I.23.020–023, Achilles now prepares for the funeral feast—but not before displaying the dead body of Hector, lying face down in the dust, I.23.024–026, next to the stand where the dead body of Patroklos is lying in state. Then, after the Myrmidons unharness their chariots, I.23.026–027, they sit down next to the ship of Achilles in order to partake of the feast, I.23.028, and the slaughter of the sacrificial animals to be eaten at the funeral feast gets underway, I.23.029–034. Nothing is said here about cooking the meat. Instead, the last thing said about this funeral feast of the Myrmidons is that the blood flowing from the mass slaughter of sacrificial animals is streaming all around the corpse of Patroklos, I.23.034. It seems as if the Myrmidons were feasting on raw meat, just as their leader Achilles had expressed the ghastly desire to cut up the mortally wounded Hector and to eat him raw, I.22.346–347. See the comment on I.22.346–348. Meanwhile, the leaders of the Achaeans come to the ship of Achilles and persuade him, with some difficulty, to leave behind the funeral feast of the Myrmidons and to come along with them to the headquarters of Agamemnon, I.23.035–038, where the order is given to prepare for Achilles some hot water for him to wash off all the blood that still covers him, I.23.039–041. Evidently, Agamemnon is preparing for an all-Achaean feast to be attended by Achilles, who is now expected to wash up before the feast begins. And it is only at this moment that we see for the first time that Achilles is still covered in gore. The blood of all the Trojans he has slaughtered on the battlefield is still on him and with him. Already before, Achilles must have been covered in gore when he had hosted the feast for that sub-set of Achaeans who were his own people, the Myrmidons. Back then, neither Achilles nor any of his Myrmidons had washed off the human blood of the killing fields before the shedding of the animal blood at the sacrifice that preceded their funeral feast. But now, for the all-Achaean feast, Achilles is expected to wash up. Not surprisingly, Achilles refuses, declaring at I.23.043–044 that he will remain covered with gore and will refrain from washing off the blood until he performs three sacred tasks. He now names these tasks at I.23.045–046: first, he will cremate Patroklos, I.23.045, and, second, he will make a tumulus that will be a sēma ‘tomb’ for Patroklos, I.23.045, and, third, he will at an earlier point cut off a long lock of his own hair as a sacrifice to be burned on the funeral pyre of his friend, I.23.046. That said, however, Achilles goes on to urge Agamemnon to continue with the plan for an all-Achaean feast, I.23.048—provided that the Achaeans follow up on their nighttime feasting by going out next morning in order to gather firewood for constructing the funeral pyre that will be used for the cremation of Patroklos, I.23.049–053. The Achaeans proceed to indulge in their feasting and then return to their shelters for a night’s sleep, I.23.054–058, while Achilles goes off without having had anything to eat, mourning Patroklos, and he finds a solitary spot on the beach, where he lies down, exhausted, and falls into a deep sleep, I.23.059–064. What will happen next, at I.23.071-076, is the apparition of the spirit of Patroklos. Before commenting on the apparition scene, however, I must pause to note that the narrative has already indicated five salient points of dysfunctionality in the preparations of Achilles for the funeral of Patroklos:

I.23.012

I.23.016

I.23.017

I.23.045

I.23.046–047

I.23.065–092

I.23.071–076

On the surface, what the psūkhē ‘spirit’ of Patroklos wants is a proper funeral for the corpse of Patroklos. But what does the psūkhē really want for itself? I ask the question this way in order to highlight a basic fact about the use of the word psūkhē in Homeric diction: as a disembodied conveyor of identity after death, the psūkhē is distinct from the body once the body is no longer alive. In view of this distinction, the answer to the question I just posed is partly evident—but also partly mystical. Here is my formulation of the answer: what the psūkhē really wants for itself is to be reunited with the body, and such a reunion must be achieved by way of a proper funeral. The part that is mystical about this formulation is the fact that the very idea of a proper funeral is a ritual construct that fits the mythological construct of the psūkhē. The ritual must be done right, and then the myth of the psūkhē will turn out to be right. So, it is imperative for Achilles to get things right in preparing a proper funeral for Patroklos. And how will Achilles make sure that the funeral of Patroklos is a proper funeral? Most important, there must be a ritually correct entombment, I.23.071, and a vital part of this entombment will be the actual cremation of the corpse, I.23.070–071 / I.23.076. Before cremation of the corpse, the psūkhē as a ‘spirit’ that used to belong to the body will be haunting the world of the living, but, after cremation, there will be no more haunting, I.23.075–076. So, what will happen to the psūkhē after cremation of the body? It is often assumed by readers of these verses at I.23.071-076 that the psūkhē as ‘spirit’, once the body is cremated, will now simply join the other psūkhai or ‘spirits’ who are already in Hādēs, and that will be the end of that. But the original Greek wording does not say that. In my opinion, what it really says gets misunderstood. What follows is a reinterpretation of I.23.071–076, divided into ten points:

Point 9. On the basis of both the internal and the comparative evidence that I have assembled so far, my formulation about the the ritual of cremation as visualized in myth can now be extended. In this extended formulation, I start with a scenario that reconstructs the initial phase of what happens to the psūkhē after the body is successfully cremated:

Point 10. I now continue with a scenario that reconstructs the next phase of what happens to the psūkhē after the body is successfully cremated. In this case, I find no internal evidence in Homeric poetry, and so I turn to the comparative evidence of Vedic poetry in Indic traditions, which show at least the broad outlines. From here on, since I now rely primarily on the Indic comparanda, I will no longer say psūkhē but simply ‘spirit’, which can serve as an adequate translation for both the Greek word and the corresponding Indic word, mánas-. This Indic word refers to the breath of life that leaves the body at death and is destined to be mystically reintegrated with the body after cremation. That said, I resume the scenario:

I.23.090

I.23.093–098

Achilles responds to the apparition in his dream, I.23.094–096, declaring to the spirit of Patroklos that he intends to do exactly what this spirit has instructed him to do. But the hero’s declaration here is interwoven with a question that he asks of the spirit: why do you appear to me and instruct me to do things that I already intended to do? This interwoven question at I.23.094–096 is most curious, since it is patently unjustifiable. I argue that the things intended by Achilles fail in more than one way to match the things intended by the psūkhē of Patroklos. There are two main reasons for making this argument:

I.23.099–107

I.23.108–126

I.23.113

I.23.124

I.23.125–126

I.23.127–137

I.23.138–153

I.23.154–162

I.23.163–183

I.23.184–191

As we will now see, the gods are well aware of the ongoing pollution, and they counteract it by way of purification, which takes the form of preserving the body of Hector from the mistreatment intended by Achilles. Right after Achilles declares once again at I.23.183 that he will expose his enemy’s body as prey to be devoured by dogs, the Master Narrator firmly contradicts him at I.23.184: no, the dogs will not be devouring the body of Hector. And why? Because the gods will not allow it. Aphrodite herself is keeping the hellish hounds away from the corpse, I.23.185–186. And the goddess is applying to Hector’s skin a salve that is ambrosio– ‘immortalizing’, thus keeping it intact and saving the beautiful flesh from any disfigurement—no matter how many times Achilles will drag the corpse behind his speeding chariot, I.23.186–187. (On the word ambroto-/ambrosio– in the sense of ‘immortalizing’, not ‘immortal’, see the relevant comment on I.16.670.) So, the goddess of sexual beauty has kept the naked body of Hector beautiful to the point of becoming sexually attractive: Hector is now the definitive beau mort, the beautiful corpse, since his dead body has been made beautiful by way of a beautiful death, une belle mort. (See HC 4§266, with bibliography on the French terminology; see also the relevant comment on I.17.050–060.) For the first time here at I.23.184–191, we see that the body of Hector was never even disfigured—despite the horrific visions of disfigurement that the Master Narrator allowed to be imagined at I.22.395–405 and even later at 1.23.1–64. (See especially the comment on I.22.395–405.) Now, all those darkly horrific visions of ugliness recede in the beautiful light of divine intervention. Not only does Aphrodite apply her immortalizing salve to Hector’s flesh, I.23.186–187, but Apollo does even more, enveloping the hero’s entire body in a divine glow that will shield it from all decay and pollution, I.23.188–191. And by now we can see that the action of the gods in perfectly preserving the dead body of Hector is an act of perfect purification that counteracts the self-pollution of Achilles in mistreating the corpse. We have already seen that the polluted thoughts of Achilles had even compromised the ritual of cremation for Patroklos. But now we will see that the saving of Hector’s body by the gods will lead to an overall purification that will in the course of time counteract not only the specific pollution of mistreating the corpse of Hector but also the overall pollution that has compromised the ritual of cremating the corpse of Patroklos. And the gods will accomplish this overall purification by saving Hector’s body as a ritually idealized corpse that is worthy of a ritually ideal cremation—which will actually take place in Iliad 24. Even before we reach the narration of that ideal cremation in Iliad 24, eight points need to be made already now about the picturing of Hector’s body as a ritually idealized corpse here at I.23.184–191:

I.23.245–248 … 256–257

I.23.257–258

I.23.326–343

subject heading(s): sēma ‘sign, signal; tomb’

(Epitomized from H24H 7§§3–6.) I concentrate here on the use of the word sēma in two verses, I.23.326 and I.23.331, concerning the sēma or ‘sign’ given by the hero Nestor to his son, the hero Antilokhos, about the sēma or ‘tomb’ of an unnamed hero. I divide my analysis into four parts:

I.23.528

I.23.841

I.23.860

I.23.888

Iliad Rhapsody 24

2016.12.31 / enhanced 2018.09.20

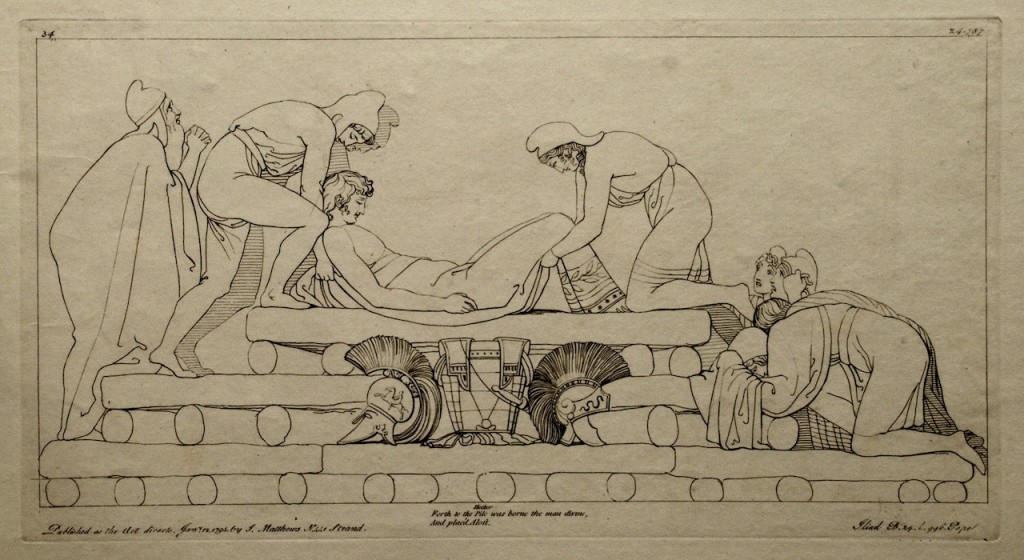

Figure 24. Mourners lament as Hector’s corpse is laid out in preparation for the funeral that closes Iliad Rhapsody 24. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 24. Mourners lament as Hector’s corpse is laid out in preparation for the funeral that closes Iliad Rhapsody 24. Copperplate etching (1795) by Tommaso Piroli, after a drawing (1793) by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.I.24.001

I.24.006

I.24.014–018

I.24.018–022

I.24.023–28

I.24.029–30

I.24.032–054

I.24.055–063

I.24.064–076

I.24.105

I.24.112–116

I.24.133–137

I.24.158

I.24.187

I.24.396

I.24.406

I.24.438

I.24.474

I.24.509–512

I.24.573

I.24.707–776

I.24.708

I.24.720–776

I.24.723–746

I.24.747–760

I.24.761–776

I.24.777–784

I.24.785–804

The corpse of Hector is placed on top of the funeral pyre, and then the pyre is lit, I.24.786–787. The next morning, the fires of the cremation are extinguished and the bones of Hector are gathered, I.24.792–795, to be placed into a larnax ‘repository’, I.24.795. A tumulus is heaped over the remains, I.24.799, and the tumulus itself is called a sēma ‘tomb’, I.24.799/801. What we see here in Iliad 24, in the conclusion to the entire epic narrative, is a perfect description of a perfect entombment after a perfect cremation—to be contrasted with the ritually flawed cremation of Patroklos as described in Iliad 23. Here I find it relevant to cite the archaeological background on the practice of cremation in the Mycenaean era. I quote a brief summary in Nagy 2015.07.22§31:

[[GN 2016.12.30.]]

Epilogue 1: Hector as the ultimate beau mort

Epilogue 2: Hector as an ideal for Athenians

Odyssey Rhapsody 1

2017.03.02 / enhanced 2018.10.06

O.01.001–010

subject heading(s): epic; theme; andra [grammatical object of anēr] ‘man’; Muse; Master Narrator; narrative subject as grammatical object; ennepein ‘narrate, tell’; polutropos ‘turning-into-many-different-selves’; epithet for narrative subject; singing as narrating

There are three main points to be made in my comments here.

O.01.001–004

O.01.001

O.01.001–002

O.01.002

O.01.003

O.01.004

O.01.005

O.01.007

O.01.008

O.01.010

subject heading(s): hamothen ‘starting-from-any-single-point-of-departure’; theā ‘goddess’; elliptic plural; Homer’s ‘I’ and Homer’s ‘we’; ellipsis of ‘we’ for ‘I’ in referring to the Master Narrator

O.01.022–026

O.01.032–034

O.01.088–095

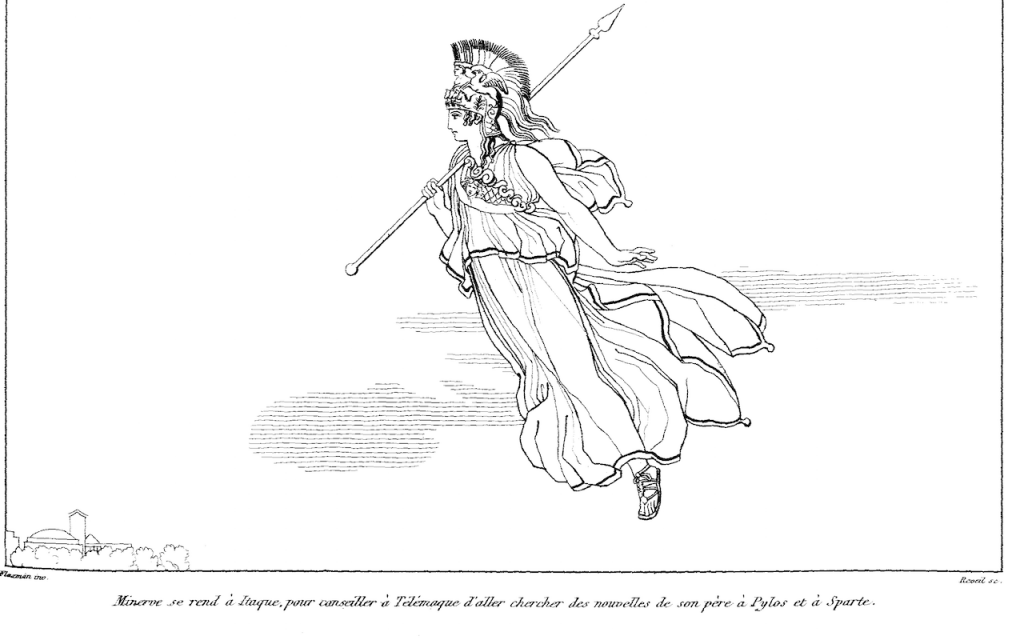

subject heading(s): journey to Pylos and Sparta; menos ‘mental power’; punthanesthai ‘learn’; akouein ‘hear’; nostos ‘homecoming, song of homecoming’; kleos ‘glory’ (of poetry)

O.01.088–089

O.01.093

The text as transmitted by Aristarchus (see Inventory of terms and names) reads:

πέμψω δ’ ἐς Σπάρτην τε καὶ ἐς Πύλον ἠμαθόεντα

‘I [= Athena] will conduct [pempein]him [= Telemachus] on his way to Sparta and to sandy Pylos’

But the text as transmitted by Zenodotus (see again the Inventory) reads:

πέμψω δ’ ἐς Κρήτην τε καὶ ἐς Πύλον ἠμαθόεντα

‘I [= Athena] will conduct [pempein] him [= Telemachus] on his way to Crete and to sandy Pylos’

O.01.103

O.01.105

O.01.153–155

O.01.241

O.01.284–286

The text as transmitted by Aristarchus (see Inventory of terms and names) reads:

κεῖθεν δὲ Σπάρτηνδε παρὰ ξανθὸν Μενέλαον·

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.‘First you [= Telemachus] go to Pylos and ask radiant Nestor

and then from there to Sparta and to golden-haired Menelaos,

the one who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.’

But the text as transmitted by Zenodotus (see again the Inventory) reads:

κεῖθεν δ’ ἐς Κρήτην τε παρ’ Ἰδομενῆα ἄνακτα,

ὃς γὰρ δεύτατος ἦλθεν Ἀχαιῶν χαλκοχιτώνων.‘First go to Pylos …

and then from there to Crete and to king Idomeneus

who was the last of the Achaeans, wearers of bronze tunics, to come back home.’

O.01.299

O.01.320–322

subject heading(s): menos ‘mental power’; Méntēs and Méntōr; hupo-mnē- ‘mentally connect’

O.01.320

O.01.325–327

O.01.326–327

O.01.338

O.01.340–341

O.01.342

O.01.346–352

O.01.383

Odyssey Rhapsody 2

2017.03.08 / enhanced 2018.10.06

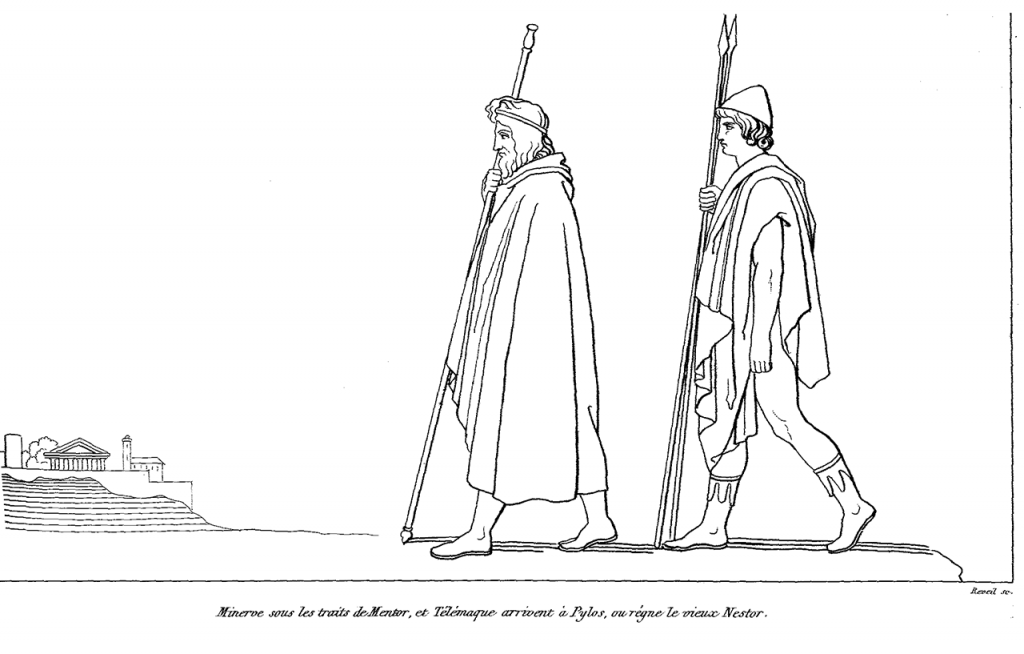

Figure 26.Telemachus with Athena as Mentor (1810). Drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 26.Telemachus with Athena as Mentor (1810). Drawing by John Flaxman. Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.02.001

O.02.006–008

O.02.026

O.02.032

O.02.035

O.02.037

O.02.044

O.02.047

O.02.067

O.02.080

O.02.085–128

O.02.092–109

O.02.121–122

O.02.163

O.02.212–218

O.02.224–228

O.02.225

O.02.234

O.02.239

O.02.262–269

O.02.271

O.02.282

O.02.313

O.02.323

O.02.350

O.02.360

Odyssey Rhapsody 3

2017.03.29 / enhanced 2018.10.06

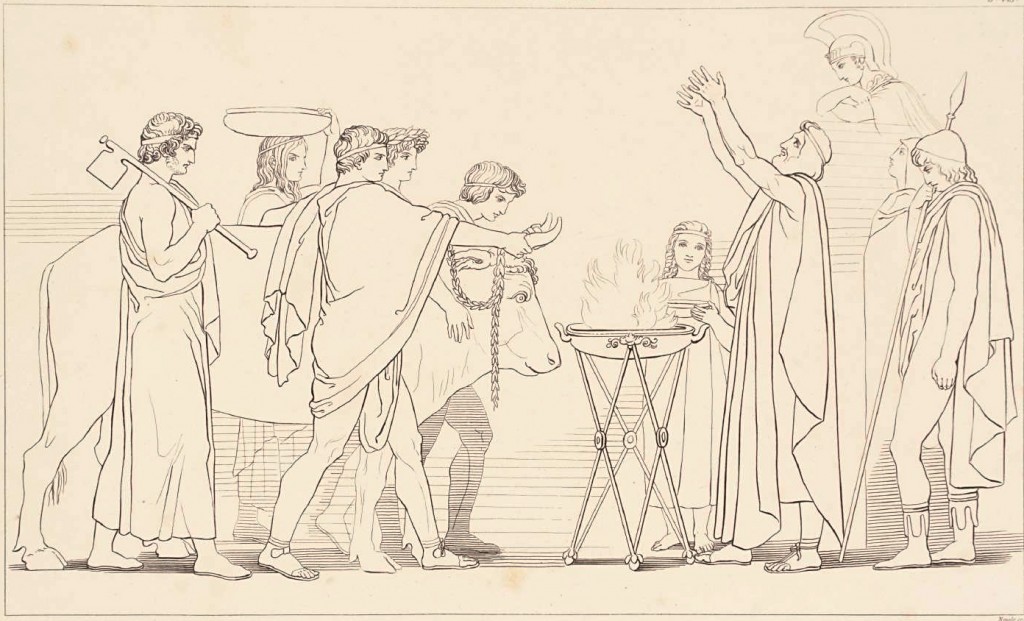

Figure 27. Nestor’s Sacrifice (1805). Engraving after John Flaxman (1755-1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported).

Figure 27. Nestor’s Sacrifice (1805). Engraving after John Flaxman (1755-1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image released under Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND (3.0 Unported).O.03.001

O.03.033

O.03.036

O.03.066

O.03.083

O.03.112

O.03.118

O.03.120–121

O.03.130–183

[§75] And here I stop to highlight the contradiction between the story as told here in the Odyssey and the story as told in Song 17 of Sappho. In the Odyssey, we see that Menelaos came to Lesbos, but there is no mention here of Agamemnon. In Song 17, by contrast, it seems that both brothers came to Lesbos [Nagy 2015§50]:

O.03.130

O.03.133–135

O.03.160–169

O.03.168–169

subject heading(s): late arrivals of Menelaos

O.03.170–178

O.03.202–224

O.03.207

O.03.262

O.03.267–271

O.03.267

O.03.464–468

Odyssey Rhapsody 4

2017.04.05 / enhanced 2018.10.06

Figure 28. “The Fair Helen.” Willy Pogany (Hungarian, 1882–1955). Image via Flickr user C. Ojeda, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

Figure 28. “The Fair Helen.” Willy Pogany (Hungarian, 1882–1955). Image via Flickr user C. Ojeda, reproduced under a CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.O.04.001–019

O.04.011

O.04.015–019

subject heading(s): ex-arkhein ‘lead off [in performing]’; molpē ‘singing-and-dancing’

O.04.043–075

[§1] The wording about to be quoted describes the very first impression experienced by the young hero Telemachus when he sees the splendor of the palace of Menelaos and Helen. We join the action as Telemachus and his traveling companion, the young hero Peisistratos, son of Nestor, are both being escorted into the palace of Menelaos and Helen:

[§2] At this point, the story proceeds to take the visitors through a series of welcoming rituals, followed by a grand dinner arranged by Menelaos as the gracious host, O.04.047–070. And now the dinner conversation gets underway, starting with words of appreciation spoken by Telemachus and intended for Menelaos. Telemachus speaks here as a grateful guest, addressing his fellow guest Peisistratos, son of Nestor, but his words are really intended for Menelaos as the generous host. I will now quote these words of Telemachus as spoken to the son of Nestor—words that not only compPaleGreennt Menelaos but also express most sincerely the young guest’s awestruck reaction to the splendor of the king’s palace:

O.04.093–116

O.04.182–185

O.04.170

O.04.186–188

O.04.220–226

O.04.227–230

Herodotus makes a point of distinguishing Homer from what he describes as the poet of the Cypria, and, in making this distinction, he actually quotes a passage from the Homeric Iliad to prove his point (Herodotus 2.116.1–2.117.1):

Σιδονίων, τὰς αὐτὸς Ἀλέξανδρος θεοειδὴς

ἤγαγε Σιδονίηθεν, ἐπιπλὼς εὐρέα πόντον,

τὴν ὁδὸν ἣν Ἑλένην περ ἀνήγαγεν εὐπατέρειαν.

ἐσθλά, τά οἱ Πολύδαμνα πόρεν Θῶνος παράκοιτις

Αἰγυπτίη, τῇ πλεῖστα φέρει ζείδωρος ἄρουρα

φάρμακα, πολλὰ μὲν ἐσθλὰ μεμιγμένα, πολλὰ δὲ λυγρά.

Αἰγύπτῳ μ’ ἔτι δεῦρο θεοὶ μεμαῶτα νέεσθαι

ἔσχον, ἐπεὶ οὔ σφιν ἔρεξα τεληέσσας ἑκατόμβας.

from Sidon, whom Alexandros [= Paris] himself, the godlike,

had brought home [to Troy] from the land of Sidon, sailing over the vast sea,

on the very same journey as the one he took when he brought back home [to Troy] also Helen, the one who is descended from the most noble father.

things of good outcome, which to her did Polydamna give, wife of Thon.

She was Egyptian. For her, many were the things produced by the life-giving earth,

magical things—many good mixtures and many baneful ones.

I was eager to return here, but the gods still held me in Egypt,

Since I had not sacrificed entire hecatombs [hekatombai] to them.

O.04.227

O.04.238–243

O.04.250

O.04.261

O.04.279

subject heading(s): eïskein ‘make likenesses, liken’

φωνὴν ἴσκουσ’ ἀλόχοισιν.

She [= Helen] was likening [eïskein] her voice to the voices of their wives.

O.04.341–344

O.04.343–344

O.04.351–362

O.04.351–353

subject heading(s): hekatombē ‘hecatomb’; failure to perform a hecatomb

O.04.354–355

O.04.363

O.04.489

O.04.512–522

O.04.512–513

subject heading(s): the temporary success of Agamemnon and the temporary failure of Menelaos

O.04.561–569

O.04.567–568

O.04.727

O.04.739

O.04.809

Odyssey Rhapsody 5

2017.04.12 / enhanced 2018.10.07

Figure 29. “Leucothea, the White Goddess, Preserving Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 29. “Leucothea, the White Goddess, Preserving Ulysses” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.O.05.001–002

O.05.047

O.05.121–124

O.05.121

O.05.123–124

O.05.136

O.05.160–161

O.05.185–186

O.05.248

O.05.273-275

O.05.308–311

O.05.333–353

O.05.396

O.05.432–435

O.05.437

O.05.458

O.05.493

Odyssey Rhapsody 6

2017.05.04 / enhanced 2018.10.07

Figure 30a. “Nausicaa” (1878), Frederick Leighton (English, 1830–1896). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 30a. “Nausicaa” (1878), Frederick Leighton (English, 1830–1896). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.06.001–002

O.06.005–006

O.06.015–017

O.06.048–053

O.06.100–101

Figure 30b. Red-figured pyxis, picturing Nereids at home, “indoors”: the Nereid with her hair down is labeled as Thaleia. Image via The British Museum.

O.06.102–109

O.06.150–152

O.06.160–168

O.06.231

O.06.273

Odyssey Rhapsody 7

2017.05.11 / enhanced 2018.10.08

nous), king of the Phaeacians. This palace and the adjacent garden of Alkinoos are not only enchanting but even enchanted, as will be argued in the comments for Rhapsody 7 here. And, as we will see later in the comments for Rhapsody 13, the garden of Alkinoos was thought to have survived on the island of Kerkyra, known in Roman sources as Corcyra and in modern times as Corfù. In ancient times, the people of Kerkyra claimed that their island was in fact the fabled realm of the Phaeacians.[[GN 2017.05.11.]]

Figure 31. View of Garitsa, region right outside the northern walls of the city of Corfu, and according to the legend the site of Alcinous’s gardens (1867). Étienne Rey (French, 1789–1867). Image via the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.

Figure 31. View of Garitsa, region right outside the northern walls of the city of Corfu, and according to the legend the site of Alcinous’s gardens (1867). Étienne Rey (French, 1789–1867). Image via the Aikaterini Laskaridis Foundation.O.07.058–062

O.07.078–081

subject heading(s): Athena and Athens; ellipsis; Erekhtheus

O.07.081–111, 112–132

O.07.167

O.07.215–221

O.07.221

O.07.256

O.07.257

O.07.321

Odyssey Rhapsody 8

2017.05.18 / enhanced 2018.10.08

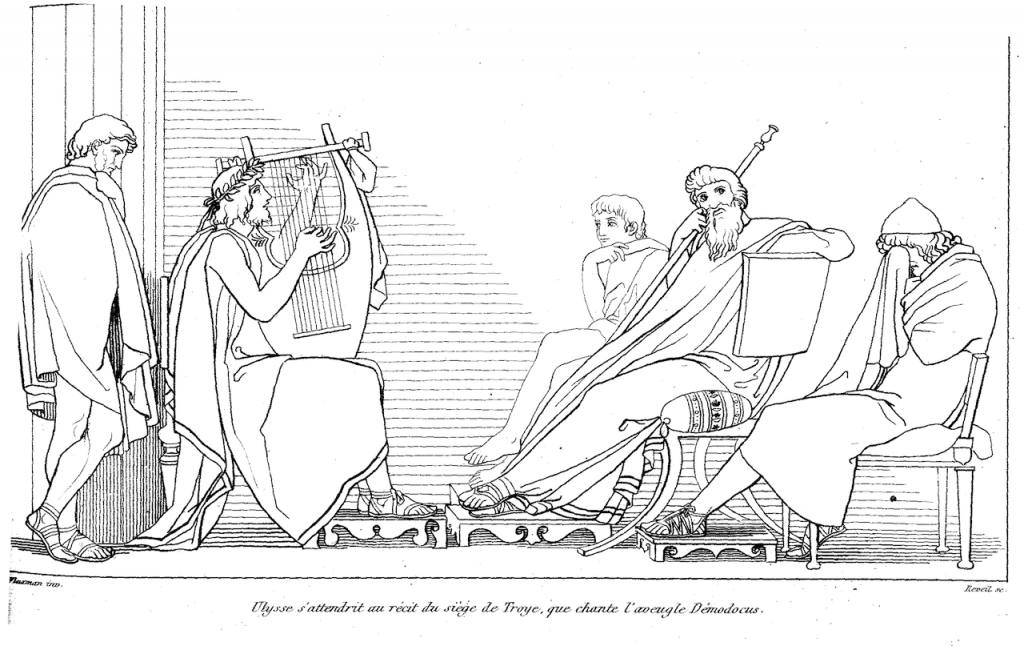

Figure 32. Blind Demodokos sings of the siege of Troy (1810), by John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 32. Blind Demodokos sings of the siege of Troy (1810), by John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.08.002

O.08.026–045

O.08.036

O.08.038

O.08.044

O.08.059–061

O.08.061

O.08.062–095

O.08.067

O.08.071–072

O.08.073–082

O.08.073–074

O.08.074

O.08.075–078

O.08.079–081

O.08.081–082

O.08.094

O.08.096–103

O.08.099

O.08.131

O.08.200

O.08.230–233

O.08.250–269, 367–369

subject heading(s): Second Song of Demodokos

O.08.259

O.08.260

O.08.261–265

O.08.266

O.08.267

O.08.367–369

O.08.370–380

O.08.390–391

O.08.429

O.08.485–498

subject heading(s): Third Song of Demodokos; metabainein ‘shift forward’

O.08.499–533

subject heading(s): Third Song of Demodokos; metabainein ‘shift forward’

O.08.499

O.08.522

O.08.527

O.08.533

O.08.570–571

O.08.581–586

Odyssey Rhapsody 9

2017.05.25 / enhanced 2018.10.08

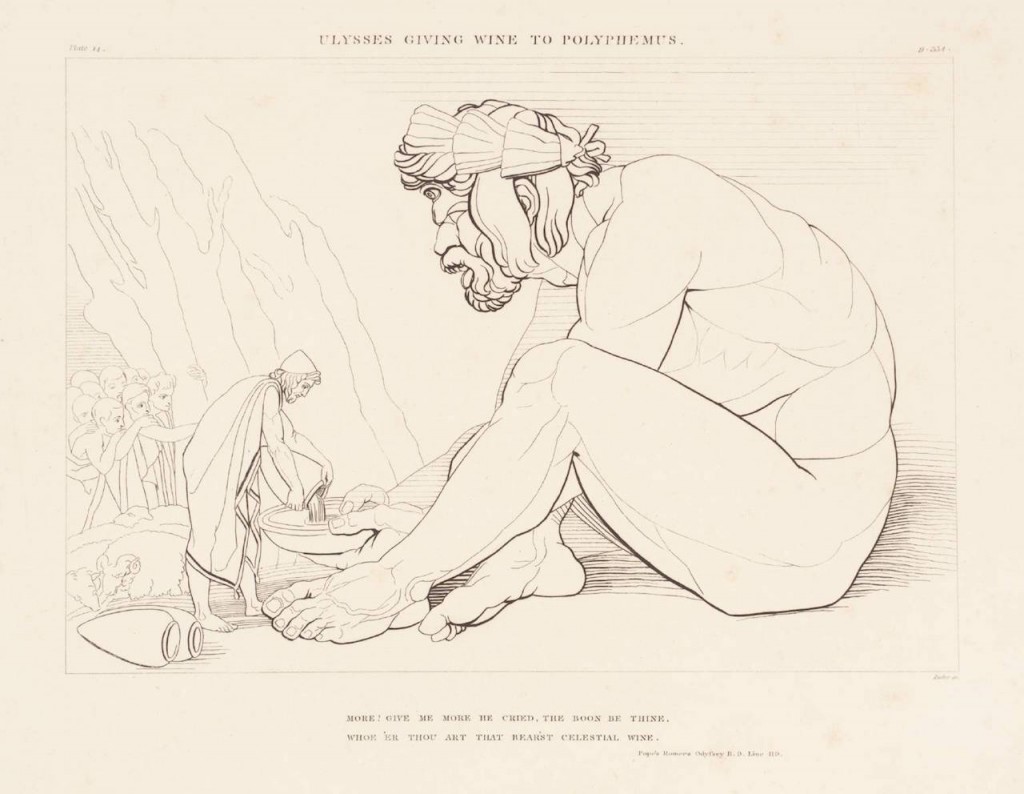

Figure 33. “Ulysses Giving Wine to Polyphemus” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 33. “Ulysses Giving Wine to Polyphemus” (1805). John Flaxman (1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund, 1996. Image via the Tate.O.09.003–011

subject heading(s): telos ‘outcome’; [kharis ‘gratification; pleasurable beauty’;] euphrosunē ‘festivity, merriment’; [ dais ‘feast’;]; stylized festival; metonymy

O.09.019–020

subject heading(s): melein ‘be-on- one’s-mind’; apo koinou

O.09.063

O.09.082–104

O.09.106–141

O.09.125–129

O.09.125

O.09.133

O.09.355–422

O.09.390–394

O.09.566

Odyssey Rhapsody 10

2017.06.01 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 34. “Circe Invidiosa,” (1892). J. W. Waterhouse (English, 1849–1917). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 34. “Circe Invidiosa,” (1892). J. W. Waterhouse (English, 1849–1917). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.10.025–086

O.10.065

O.10.134

O.10.135

O.10.189–202

O.10.190–193

subject heading(s): mētis ‘mind, intelligence’

O.10.245

O.10.330–331

O.10.379

O.10.450

O.10.490–495

subject heading(s): psūkhē ‘spirit’; phrenes ‘heart, thinking’; teleîn ‘reach an outcome; bring to fulfillment (in active forms of the verb)’

O.10.493

O.10.508–512

O.10.516–520

O.10.521–537

O.10.521

O.10.536

O.10.551–560

Odyssey Rhapsody 11

2017.06.08 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 35. “Teiresias appears to Ulysses during the sacrifice,” (1780–1785). Henry Fuseli (German, 1741–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 35. “Teiresias appears to Ulysses during the sacrifice,” (1780–1785). Henry Fuseli (German, 1741–1825). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.11.012–019

O.11.020–022

O.11.024–036

O.11.029–036

O.11.029

O.11.051–083

O.11.075–078

subject heading(s): sēma ‘sign, signal; tomb’; teleîn ‘reach an outcome; bring to fulfillment (in active forms of the verb)’

O.11.090–137

subject heading(s): revelations of Teiresias; [nóos ‘mind’;] nostos ‘homecoming, song of homecoming’

O.11.091

O.11.099

O.11.100–118

O.11.119–137

This stretch of the prophecy made by Teiresias, O.119–137, will extend beyond the plot or narrative frame of the Odyssey as we know it. (What follows is an epitome of H24H 11§§33, 41–44.) In an essay entitled “Sēma and Noēsis: The Hero’s Tomb and the ‘Reading’ of Symbols in Homer and Hesiod” (GMP 202–222), I analyzed at some length the mystical prophecy spoken by the psūkhē ‘spirit’ of the mantis ‘seer’ Teiresias at O.11.119–137 about an odyssey beyond the Odyssey. As I argued in that essay, the verses of this prophecy point to the future death of Odysseus and to the mystical vision of his own tomb, where he will be worshipped as a cult hero. My argument can be divided into four parts:

Part 4. This is not to say, however, that Ithaca was the only place where Odysseus was worshipped as a cult hero. From the testimony of Pausanias 8.44.4, for example, we see traces of a hero cult of Odysseus in landlocked Arcadia, which is located in the Peloponnesus and which is as far away from the sea as you can possibly be in the Peloponnesus. Here is the relevant testimony of Pausanias 8.44.4:

O.11.124

O.11.136–137

O.11.138–224

O.11.151

O.11.179

O.11.201

O.11.217

O.11.222

O.11.225–329

O.11.290

O.11.296

O.11.300

O.11.330–385

O.11.433

O.11.467–540

O.11.475–476

O.11.478

O.11.489–491

O.11.550–551

O.11.558–560

O.11.568–571

O.11.597

O.11.601–626

O.11.601

O.11.620–624

O.11.631

O.11.636–640

Odyssey Rhapsody 12

2017.06.15 / enhanced 2018.10.08

Figure 36. “Ulysses and the Sirens” (ca. 1909). Herbert James Draper (English, 1863–1920). Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 36. “Ulysses and the Sirens” (ca. 1909). Herbert James Draper (English, 1863–1920). Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.12.001–004

(What follows is epitomized from H24H 10§§31, 36–38, 42.)

Part 3. In some poetic traditions, the mystical subnarrative of the hero’s nostos can even be foregrounded, as in these verses of Theognis (1123–1128):

O.12.004

O.12.014–015

subject heading(s): Elpenor; coincidence of opposites; the tomb of Odysseus revisited

The story of Elpenor’s death was told at O.10.551–560. In the comment on those verses, I already noted that the relevance of this figure to the homecoming of Odysseus is signaled at O.11.051–083, and, further, here at O.12.014–015. Here we see Odysseus and his men making for Elpenor a tomb by heaping a tumulus of earth over the seafarer’s corpse and then, instead of erecting a stēlē or vertical ‘column’ on top, they stick his oar into the heap of earth. (What follows is epitomized from H24H§§47–50.)

O.12.021–022

subject heading(s): mystical return to light and life

O.12.068

O.12.069–070

subject heading(s): Argo; melein ‘be on one’s mind’

O.12.124

O.12.132

O.12.176

O.12.184–191

subject heading(s): Song of the Sirens

O.12.184

O.12.447–450

Odyssey Rhapsody 13

2017.06.22 / enhanced 2018.10.08

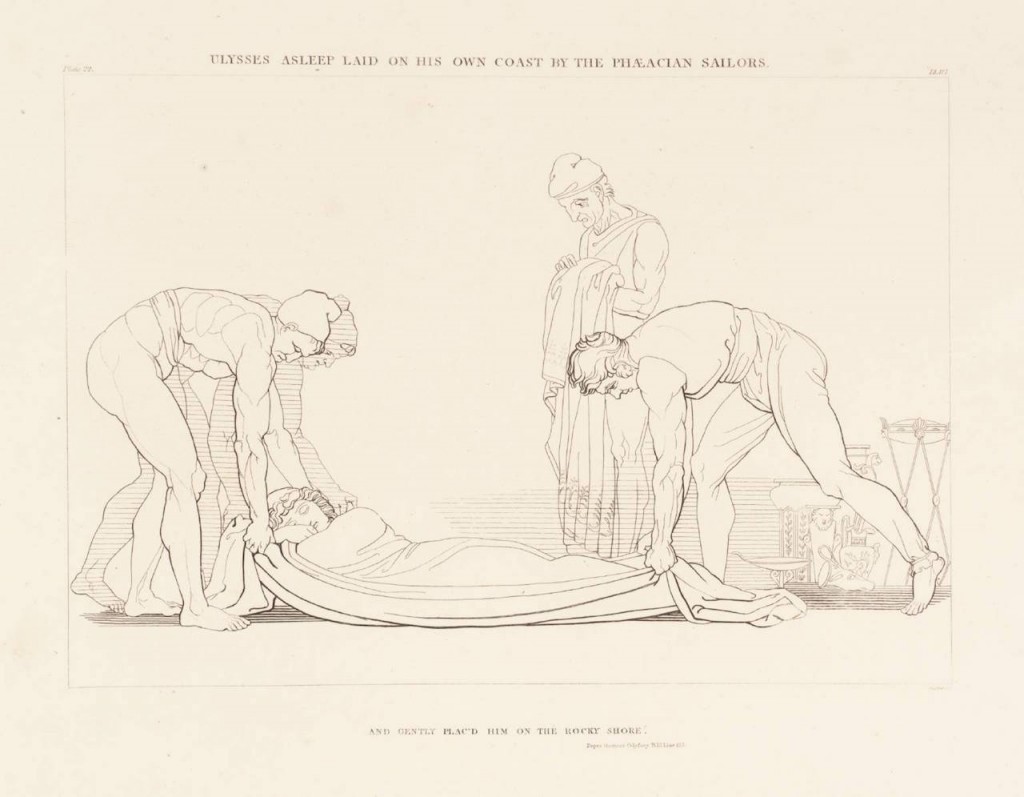

Figure 37. “Ulysses Asleep Laid on his Own Coast by the Phaeacian Sailors” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

O.13.023

O.13.024–028

subject heading(s): melpesthai ‘sing-and-dance’

(What follows is epitomized from MoM 4§§35–38.)

O.13.024–025

O.13.027

O.13.028

O.13.078–095

subject heading(s): [nóos ‘mind, thinking; consciousness’;] nostos ‘homecoming, song of homecoming; return; return to light and life’

O.13.081–083

O.13.149–152

subject heading(s): petrified ship; enveloping mountain

O.13.155–158

subject heading(s): petrified ship; enveloping mountain

O.13.158

subject heading(s): a formulaic variant

O.13.160–164

O.13.165–169

O.13.175–177

subject heading(s): prophecy of Nausithoos

O.13.178–179

subject heading(s): prophecy of Nausithoos

The audience of our Odyssey already knows this prophecy as recapitulated in O.13.173–177, because Alkinoos had already “quoted” it to Odysseus at O.08.565-569. The textual transmission of O.08.565–569 and O.13 173–177 leaves the two passages matching almost exactly, word for word. There is some degree of non-matching, though: for example, the ship is εὐεργέα ‘well-built’ in most manuscripts at O.08.567 vs. περικαλλέα ‘very beautiful’ in most manuscripts at O.13.175, while the mutually alternative forms are attested in a minority of manuscripts at both places. In terms of oral poetics, such variation may be justified even where the “quoting” of a character’s words happens to be a narrative requirement of the composition, as it is here. At that earlier point in the narrative, however, Alkinoos had said something in addition, which he does not say now (O.08.570–571):

O.13.180–182

O.13.182–183

subject heading(s): a possible way out for the Phaeacians

O.13.182–183

O.13.187

O.13.256–286

O.13.299–310

Excursus on O.13.158

Moreover, there is immediate contextual as well as formulaic evidence to support the argument that mēde ‘but not…’ is a functioning compositional variant in the formulaic system. Let us consider the wording of Zeus in his answer to Poseidon’s angry questioning at O.13.145:

This open-ended wording of Zeus matches formulaically the wording of Alkinoos, when he had originally “quoted” the prophecy of his father, O.08.570–571:

The formulation of Zeus, then, in leaving it still undecided whether or not the Phaeacians are to be ‘enveloped’, can be used as evidence to argue that mēde ‘but not…’ is indeed a genuine compositional alternative to mega de ‘and a huge…’.

Odyssey Rhapsody 14

2017.06.29 / enhanced 2018.10.09

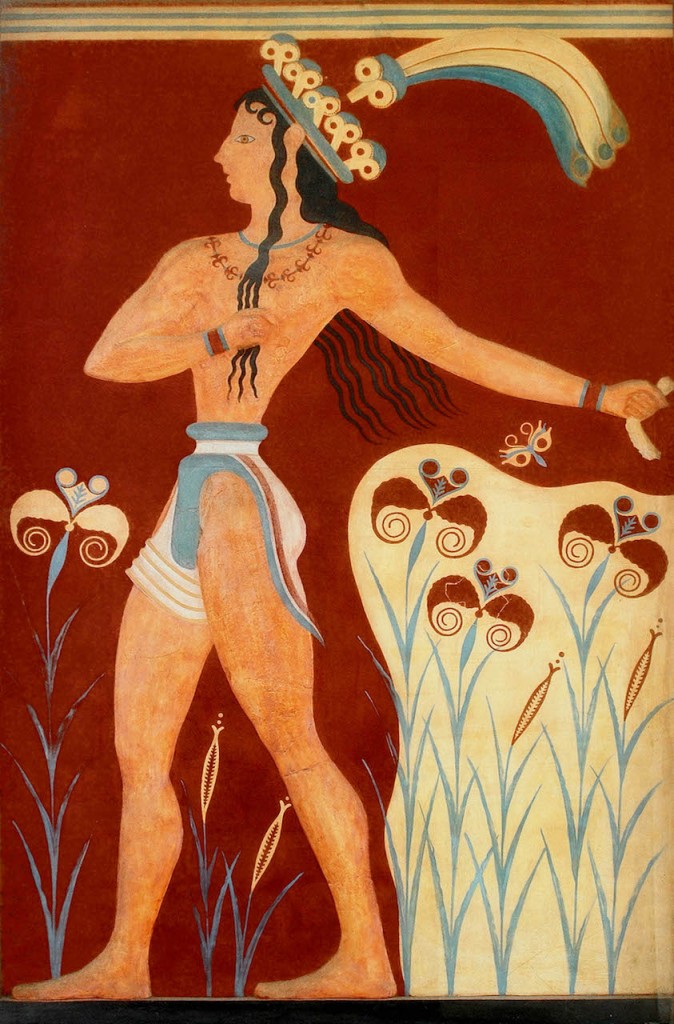

Figure 38. Minoan—probably Neopalatial—fresco commonly known as the “Lily Prince.” Whatever the exact type of this personage (perhaps a crowned acrobat, according to the interpretation of Maria Shaw), the Lily Prince is certainly a Minoan of elite standing. Public domain image based on a famous watercolor by Émile Gilliéron of a reconstruction by Arthur Evans. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 38. Minoan—probably Neopalatial—fresco commonly known as the “Lily Prince.” Whatever the exact type of this personage (perhaps a crowned acrobat, according to the interpretation of Maria Shaw), the Lily Prince is certainly a Minoan of elite standing. Public domain image based on a famous watercolor by Émile Gilliéron of a reconstruction by Arthur Evans. Image via Wikimedia Commons.O.14.055

O.14.063

O.14.109

O.14.124–125

O.14.126

O.14.135

O.14.192–359

O.14.199

subject heading(s): ellipsis; elliptic plural

O.14.216

O.14.337

O.14.371

O.14.403

O.14.418–438

O.14.440–441

O.14.462–506

O.14.462–467

subject heading(s): festive poetics

The wording here, as delivered by the disguised Odysseus to Eumaios, is cognate with the poeticized replication of a festive occasion in the words of Pindar, Nemean 7.75–76:

O.14.508

Odyssey Rhapsody 15

2017.07.03 / enhanced 2018.10.12

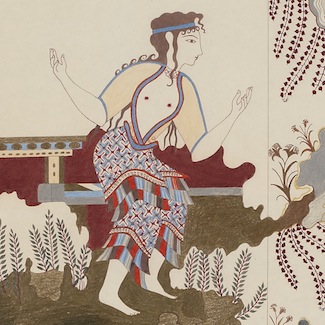

Figure 39. Detail from a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past. Minoan Crete through the eyes of Mark Cameron. 1999. Catalogue curated by Doniert Evely. Athens: British School at Athens; and N. P. Goulandris Foundation, Museum of Cycladic Art. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.

Figure 39. Detail from a fresco found at Hagia Triadha in Crete. Reconstruction by Mark Cameron, p. 96 of the catalogue Fresco: A Passport into the Past. Minoan Crete through the eyes of Mark Cameron. 1999. Catalogue curated by Doniert Evely. Athens: British School at Athens; and N. P. Goulandris Foundation, Museum of Cycladic Art. Reproduced with the permission of the British School at Athens. BSA Archive: Mark Cameron Personal Papers: CAM 1.O.15.001–009

O.15.001–003

O.15.140

O.15.247

O.15.249

O.15.250–251

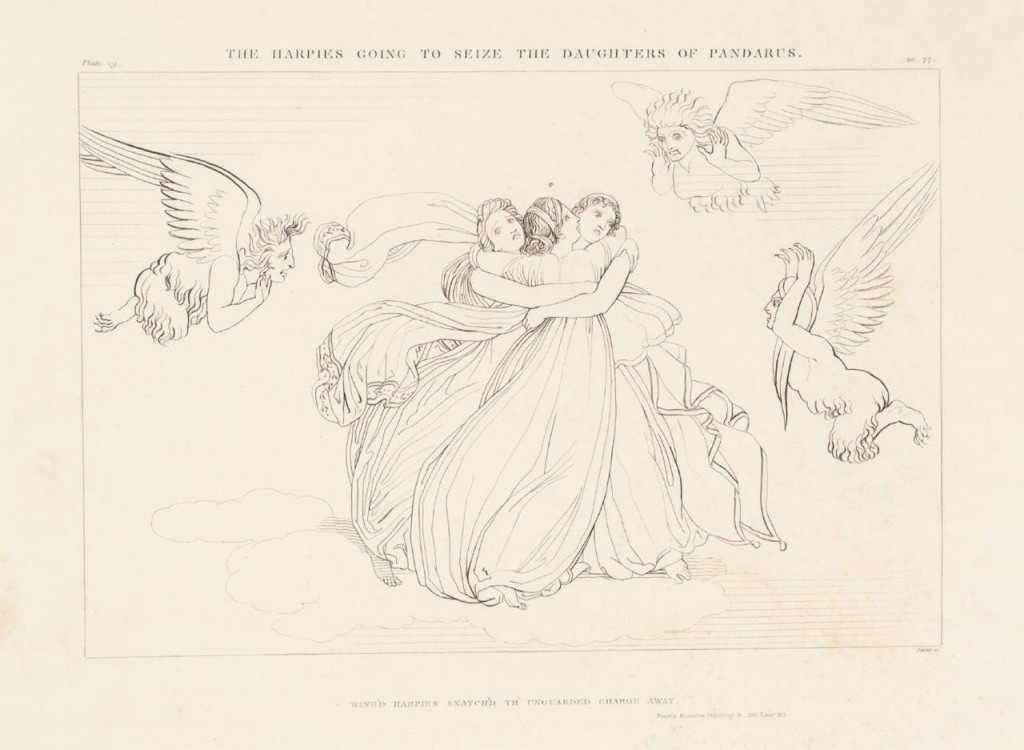

Here at O.15.250–251, Ēōs the goddess of the dawn abducts the beautiful young hero Kleitos by way of ‘snatching’ him away, as expressed by the verb harpazein ‘snatch, seize’. The picturing of such an abduction is part of an overall mythological complex that I analyzed in some detail in GMP 242–245. I epitomize that analysis in what follows:

Part 1. Here is an inventory of verbs expressing the abduction of beautiful heroes by divinities:

O.15.253

O.15.305

O.15.329

O.15.341–342

O.15.491

O.15.521–522

Odyssey Rhapsody 16

2017.07.06 / enhanced 2018.10.12

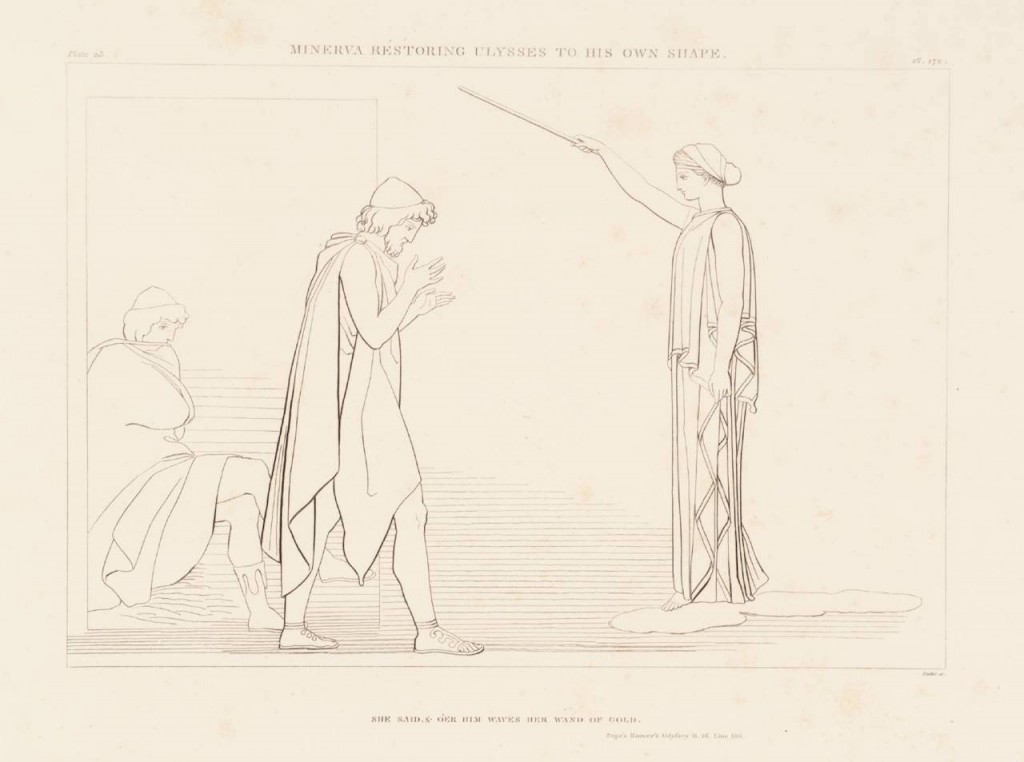

Figure 40. “Minerva Restoring Ulysses to his Own Shape” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 40. “Minerva Restoring Ulysses to his Own Shape” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.16.062–064

O.16.076

O.16.086

O.16.161

O.16.164

O.16.172–212

subject heading(s): homoio- ‘similar to, same as’; eïskein ‘make likenesses, liken’[; asaminthos ‘bathtub’]

O.16.214

O.16.283

O.16.418–432

Odyssey Rhapsody 17

2017.07.13 / enhanced 2018.10.13

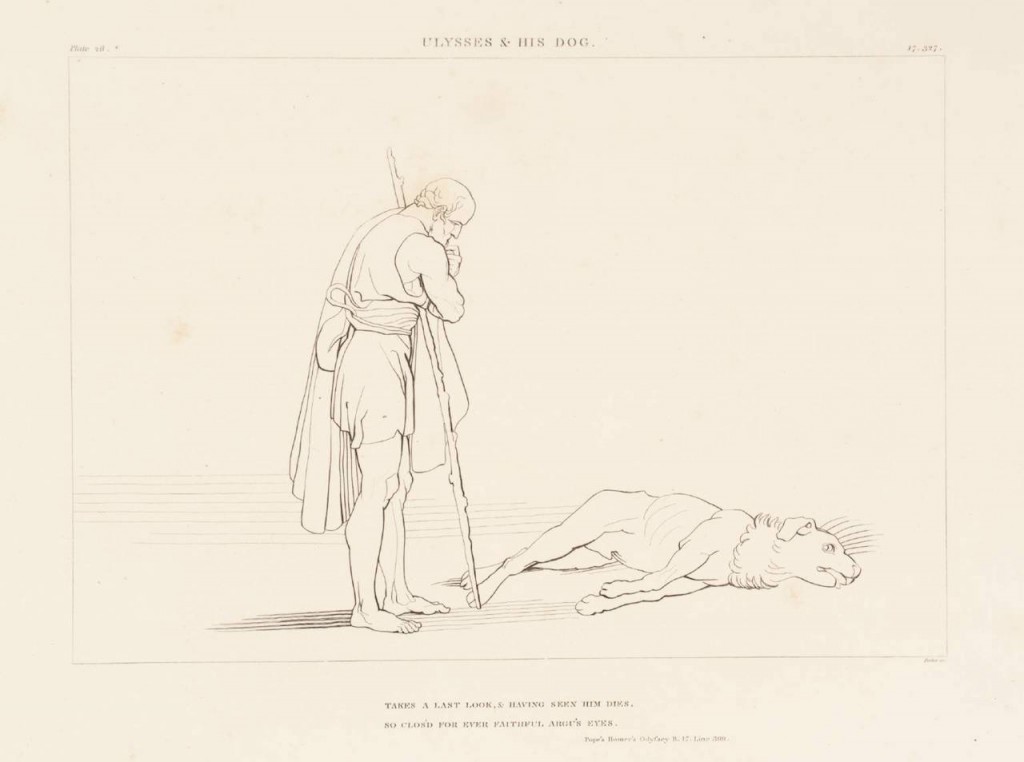

Figure 41. “Ulysses and his Dog” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 41. “Ulysses and his Dog” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826). Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.17.011

O.17.019

O.17.056

O.17.062

O.17.111

O.17.113

O.17.228

O.17.251–253

O.17.261–263

O.17.273–289

O.17.292

O.17.332

O.17.336–368

O.17.381–391

O.17.381–391

O.17.384–385

O.17.494

O.17.496–497

O.17.513–521

Odyssey Rhapsody 18

2017.07.20 / enhanced 2018.10.13

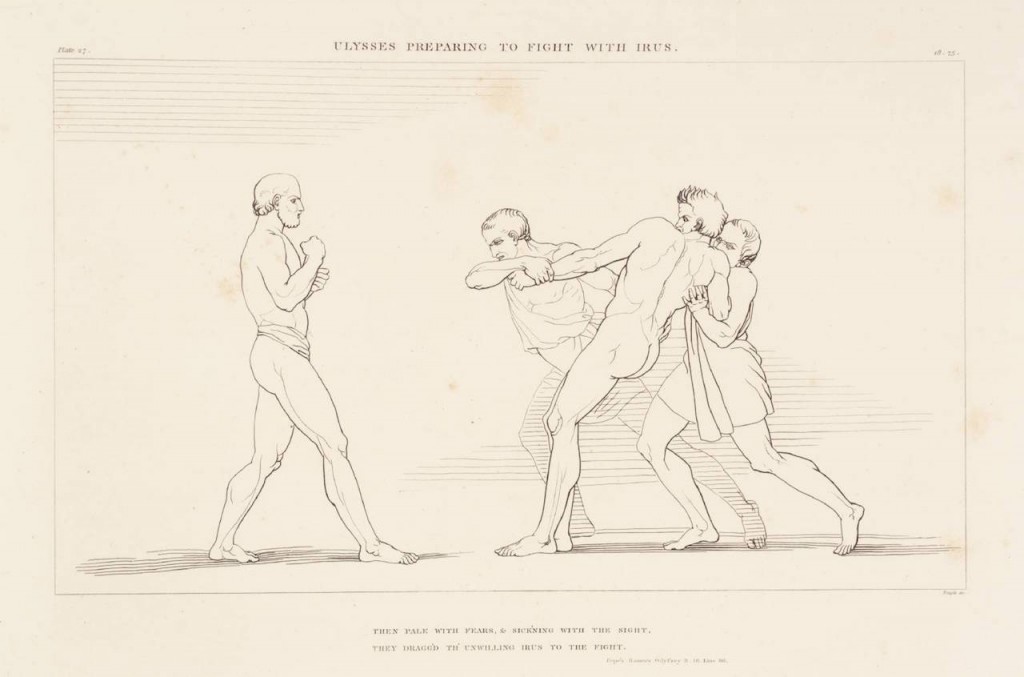

Figure 42. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.

Figure 42. “Ulysses Preparing to Fight with Irus” (1805). John Flaxman (English, 1755–1826) Purchased as part of the Oppé Collection with assistance from the National Lottery through the Heritage Lottery Fund 1996. Image via the Tate.O.18.001–117

O.18.001–004

subject heading(s): Iros; mock epic; margos ‘gluttonous, wanton’; language of praise/blame; blame poetry; praise poetry; Margites; Thersites; “speaking name” (nomen loquens)

Here I leave untranslated the synonyms īs and biē, both of which I had previously translated as ‘force, strength, violence’ in the note at O.18.001–117. As I already observed in that note, appearances here are deceiving: Iros looks strong on the outside but he is weak on the inside, and the exposure of his weakness will prove to be something that is ridiculed in epic. The act of ridiculing is the program, as it were, of mock epic, but here the mocking is reversed: now it is epic that will be mocking mock epic. As we are about to see, epic will overcome mock epic. Odysseus, even though he looks weak on the outside, will beat up on Iros, who looks strong on the outside. The mock epic form to which the epic refers here is signaled by a most telling word: it is margos ‘gluttonous, wanton’, at O.18.002, describing the gastēr ‘stomach’ of Iros, who stands out as an ostentatiously greedy consumer of food and drink, O.18.002–003. A character who is margos is not just a negative example of lowly humans in general: in the poetic language of praise/blame, such a character is a negative example of lowly poets in particular. A lowly man who is margos ‘gluttonous, wanton’ is to be seen generically as a greedy blame poet. Such a blame poet, as we will now see, is typical of a poetic form that I describe here as mock epic. We can see the formal features of such a poetic form at the very beginning of Rhapsody 18, where the wording matches in syntax the beginning of a mock epic known as the Margites. There the main character to be introduced on stage, as it were, is described not as a ptōkhos ‘beggar’, as here at O.18.001, but as a poet who turns out to be a blame poet. I show here the actual wording that we find at the beginning of that mock epic (Margites F 1 ed. West):

As we see from the explicit description here, Margites is an aoidos ‘singer’: that is, he is a poet. Moreover, he is a blame poet, as we see even from the morphology of his name Margī́tēs, derived from the adjective margós ‘gluttonous, wanton’. This “speaking name” (nomen loquens) Margī́tēs is morphologically parallel to another “speaking name,” Thersī́tēs, which means ‘the bold one’ (tharsos/thersos is ‘boldness’ in negative contexts of blame poetry). This character named Thersites is represented in the Iliad as a blame poet of the worst kind: see the comments at I.02.214, I.02.216, I.02.217–219, I.02.221, I.02.222, I.02.224, I.02.225–242, I.02.235, I.02.241–242, I.02.243, I.02.245, I.02.246–264, I.02.246, I.02.247, I.02.248–249, I.02.251, I.02.255, I.02.256, I.02.265–268, I.02.269–270, I.02.275, I.02.277. In the narrative about Thersites in the Iliad, as I pointed out in my comments on the verses I just listed, it is clear that blame poetry is antithetical not only to praise poetry but also to epic, and that epic has the power to blame, in its own right, this blame poetry. Thus, epic can defeat blame poetry, making it an object of ridicule just as blame poets attempt to make epic an object of ridicule. When Odysseus beats up on Thersites in the Iliad, epic is defeating blame poetry. Similarly, when Odysseus beats up on Iros in the Odyssey, epic is defeating blame poetry and, further, epic is also defeating mock epic. In the case of the Margites, this mock epic starts off mock seriously by describing the poet simply as a poet, though he will turn out to be a blame poet as the narrative proceeds. The metrical form of such mock epic is a combination of two kinds of verses: (1) dactylic hexameters, which are the medium of epic, and (2) iambic trimeters, which had once been the medium of mock poetry in general—the word for which is iambos (BA 243–252). A case in point is what we find in the attested fragments of the Margites: in the three verses of this poem’s beginning, already quoted above, the first two verses are dactylic hexameters, to be contrasted with the third verse, which is an iambic trimeter (Nagy 2015.10.15§§28–29). At a later point in this same fragmentary poem, we see other such iambic trimeters, the most notable example of which is this verse (Margites F 201.1 ed. West F 4b.1):

πόλλ’ οἶδ’ ἀλώπηξ, ἀλλ’ ἐχῖνος ἓν μέγα.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

The same verse is attested in a fable, “The Fox and the Hedgehog,” which is embedded in blame poetry attributed to Archilochus (F 201.1 ed. West):

πόλλ’ οἶδ’ ἀλώπηξ, ἀλλ’ ἐχῖνος ἓν μέγα.

The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.

O.18.006–007

O.18.009

O.18.015–019

subject heading(s): phthoneîn ‘begrudge’; blame poetry; olbos ‘prosperity’

O.18.073–074

O.18.079–087

O.18.085–087

O.18.115–116

O.18.204

O.18.233

O.18.235–240

O.18.289

O.18.321–326

O.18.347

O.18.350

O.18.366–386

O.18.390

O.18.424

Odyssey Rhapsody 19

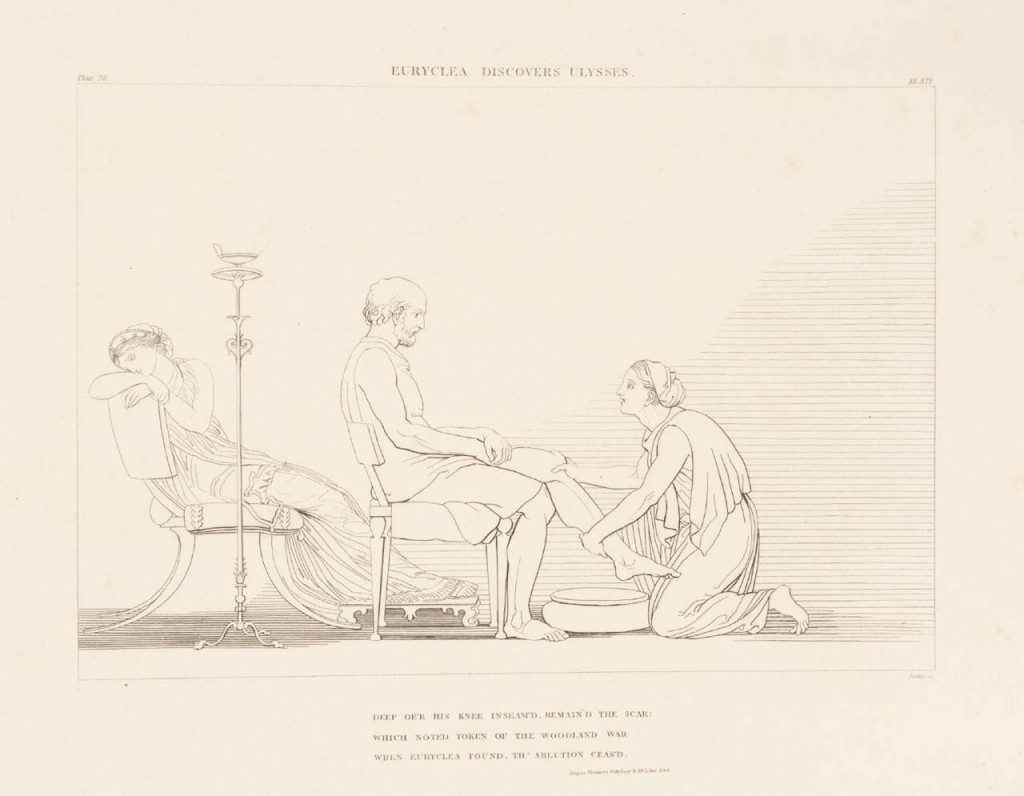

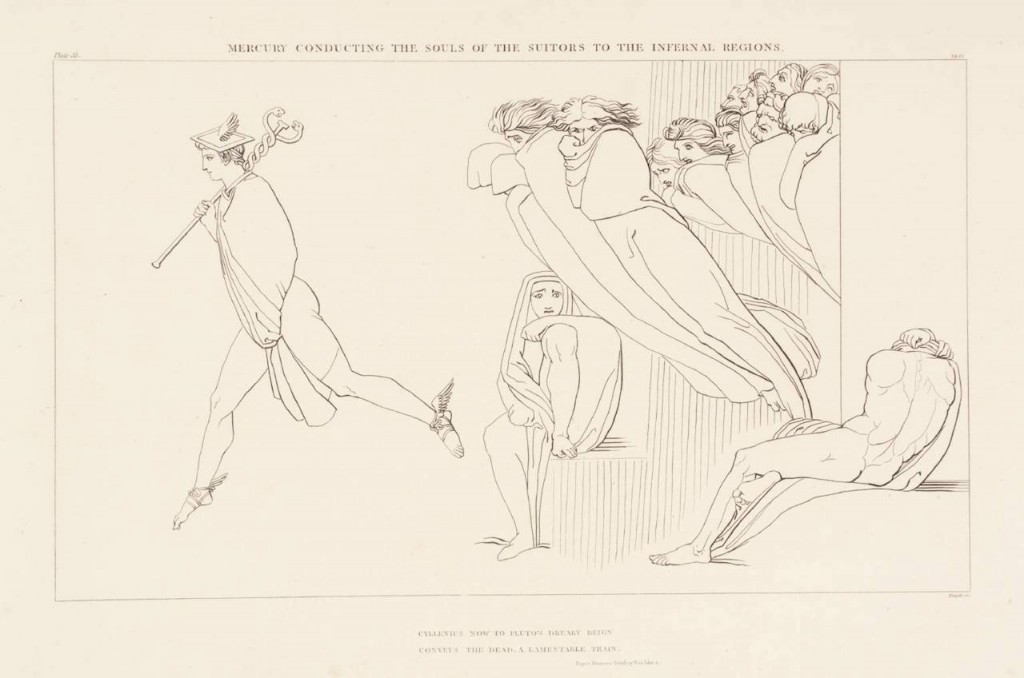

2017.07.24 / enhanced 2018.10.13