2022.03.19 | Gregory Crane

The study of Greco-Roman culture can exert a purposeful and transformative role in Europe’s development of a more just multinational and multiethnic society. This is a topic about which I have thought and on which I have spoken for years. Technology has begun to change the ways in which we can relate to sources in different languages from different cultural contexts. Those nascent changes are by no means deterministic – the technology can develop in more and less helpful directions and its development can move under very different influences. Likewise, the study of Greece and Rome can be appropriated by groups such as white supremacists or more narrowly Eurocentric nationalists (for whom whiteness is a necessary but far less sufficient condition). Therefore my own work seeks for constructive ways by which emerging technologies for reading and the study of Greco-Roman culture can together help foster a society that is more just and affords greater happiness to its citizens.

On the one hand, the ideas that I put forward and the concrete work that I describe are experiments. I expect that they will evolve in unexpected ways in the years to come. On the other hand, the basic outlines of work that needs to be done are emerging. If we seek to ignore or dismiss intellectual practices that new technologies make possible, then we leave a vacuum that others will fill who may not share our intellectual or cultural values. The work that we have done over the past fifteen years has led me to two basic conclusions.

First, we can address a crisis that students of Greco-Roman culture have acknowledged. The Department of Classics at Princeton University made headlines in the spring of 2021 by allowing students to major in the study of Greco-Roman culture without being required to study Ancient Greek or Latin, much less French, German and Italian, the languages of secondary scholarship that 20th century classicists were expected to be able to read. This addresses a serious problem: many potential students of Greco-Roman culture have not had an opportunity to begin the study of Greek or Latin in secondary school and this disadvantage disproportionately affects students of color.1 Removing the requirement to study Greek and Latin removes a barrier but it does nothing to address the disadvantage that students face when they depend entirely upon English translations. From my perspective as a philologist, true understanding of a document only begins when we push beyond the limits of a translation and grapple with ideas that cannot be properly represented in our native language, whether that is English or some other language.

Our methods of teaching Greek, Latin and other languages still generally train students to work with printed, and static, source texts that cannot explain themselves to their readers. Change has come so quickly that virtually no one recognizes what has happened or has the analytical tools by which to assess critically the implications of that change. In the last fifteen years, more than one million words of Ancient Greek source texts have been manually annotated with information about their dictionary entry, part of speech, and syntactic function. A reader with a basic understanding of the annotation scheme and a reasonably literal translation can begin to work directly with the source text. When we begin to pair these linguistic annotations with born-digital translations aligned at the word and phrase level with the original and designed to illustrate the workings of the source text, we have an interactive reading environment that goes far beyond interlinear translations produced as cribs for secondary school students or linguistically annotated texts published for linguists.

A million words of Ancient Greek is, in practice, an infinite space in that virtually none of our students would ever be able to cover so much Greek and Latin as undergraduate majors, given the way that the languages are currently taught. The Harvard Classics Department for decades examined its majors’ ability to read texts from a reading list of Greek and Latin. Since we have most of the sources in this list in digital form, I was able to establish that this list amounted to roughly 150,000 words of Greek and Latin. In practice, students only needed to read about half this list (majors in Greek and Latin both could pick and choose which questions they answered, while majors in Greek or Latin each faced 75,000 words). Some years ago, the Harvard department did away with this list. It was no longer practical to expect majors to be able to master this much: students typically are able to read a short work in the original (c. 3,000-5,000) in the first year and then slowly start reading in the second year–unless students start the languages in their first semester, it is difficult for them to read multiple authors carefully.

Many of those who go on to get PhDs in Greco-Roman studies will attend a post-baccalaureate program or get a terminal MA to gain more experience with Greek and Latin. The largest reading lists of Greek and Latin for PhD programs amounted to roughly one million words and I doubt that most students will have read more than a fraction of these lists before they take the Phd exams that assess their knowledge of Greek and Latin. Not everything that our students will want to read may be in the million words of annotated Greek that already exist, but that million words of Greek constitutes a corpus far larger and more complex than our students can exploit whether at the graduate or undergraduate level.

We should not be removing requirements to study Ancient Greek and Latin. We should be providing new models of instruction that show our students how to leverage the extraordinarily powerful tools that already exist and that are growing in size and power. Such instruction includes the ability to assess what readers can and cannot do with these tools. Leipzig PhD student Farnoosh Shamsian, however, has shown that that, with a semester of training, students are able to critique and revise modern translations in light of the Greek original and to explore the usage of Greek terms that translators will render into different words (e.g., erôs in Plato, which describes desire, and agapê in the New Testament, which describes the affection that Christians should cultivate, both often are translated as “love”).2 Students in a drama class could master every linguistically significant feature in the speeches of a major role in a Greek play so that they could perform with sufficient understanding, both in English and in Greek, to generate feeling and power. And if students trained to work with linguistically annotated corpora lack some of the skills of traditionally trained students of Greek, they will also be able to pose questions that are not feasible for those with traditional training alone. The ability to contribute to our understanding of ancient languages is being reinvented and decentralized.

Second, we no longer need to depend solely on manually annotated texts. Advances in the power of our computing hardware have fostered explosive growth in our ability to exploit methods from machine learning in general and computationally expensive deep learning in particular. (We will provide examples of such progress when we look at current machine translation and automatic linguistic annotation in the final section below). The manually annotated corpora can now be used to train generalized models which can provide serviceable initial annotations for new texts. The same advances in machine learning have transformed the quality of machine translation from many modern languages into English. I will return to this with a practical example involving Serbian in a later section of this essay. For now I will advance the hypothesis that, on average, readers with no training in French, German or Italian who were trained to make critical use of both machine translation and of automated linguistic annotation would understand, and could be shown via formal assessment to understand, more about the content of publications in these languages than professional classicists using a dictionary to work through the French, German and Italian publications. If the reader with no knowledge of the languages had access to a range of methods for analyzing and visualizing large collections of scholarly publications, they would acquire a far broader and deeper command of the scholarly literature than those who depend upon traditional, manual methods.

I now regularly require my students, undergraduate and graduate, to report on secondary sources in languages that they do not know. I assigned a chapter from Tycho von Wilamowitz’s book on Sophocles3 where the source was not only in rather complex academic German of the early 20th century but the machine readable text was uncorrected output, automatically generated from a page image with Optical Character Recognition (OCR) software. I believe that the students understood the basic content of what the text said quite as well as most conventionally trained anglophone Classicists. Many professional classicists would have avoided such a text because it would take too much work to read.

I allowed my students to rely solely on the results of machine translation because it would have taken too much time to teach them how to use the linguistic annotations about the syntax. If, however, they had learned Greek by using annotated corpora, the use of such annotations would have been a natural scaffolding for them and they could have used automated linguistic annotations to clarify parts of the machine translation that were unclear. I will return to this at the end of this paper.

Some observers may (as indeed I would once have responded) deplore the practice of exploiting technologies to hack sources in languages that we do not know. But my own preliminary research in 2015 determined that the number of citations in Anglophone journals to secondary sources that are not in English had collapsed over the previous sixty years. The number of citations to German, French and Italian publications in the 1956/1957 issue of the Transactions of the American Philological Association (TAPA) were 33%, 12% and 8% – only 48% of the citations pointed to English publications. Those numbers declined to 22%, 7.5%, and 3% in the 1986 issues of TAPA and the American Journal of Philology (AJP). In 2014, the figures were 8%, 3% and 4% in AJP, 11%, 6% and 4% in TAPA. Roughly 80% of citations were to English-language publications (84% in AJP, 80% in TAPA). Our practices of learning and using foreign language sources have led to increasingly parochial views of scholarship.4

Third, the more important impact may, in the long run, not be that we read scholarship in the traditionally hegemonic languages that have dominated the scholarship on Greek and Latin for generations. I think it will be far more important that we can begin to explore scholarship about, and reception of, Greco-Roman antiquity in a far wider range of languages in Europe and beyond.

I do not believe that ambitious young scholars should not learn modern languages well but I do think that we can use our limited cognitive resources to learn different and more cultural heterogeneous collections of languages. If I were a first year undergraduate again and choosing the languages that would shape my career, I would never consider the all-European configuration of French, German and Italian that has dominated scholarship on Ancient Greece and Rome in the past. I would consider Spanish – and this would be New World Spanish. My limited experience with students from Latin America, both Spanish and Portuguese speaking, suggests that there could be an enormous dynamic future for Greco-Roman culture if we can break the assumption that this culture belongs only to Europe and that assigns to the Spanish and Portuguese of Europe a cultural authority that alienates speakers of these languages from the Western Hemisphere. I would also consider Modern Standard Arabic, both because that would open up the far understudied and underemphasized translation movements from Greek to Arabic (c. 800 to 1000 CE) and from Arabic into Latin (c. 1200 CE)5 – world historic transfers of ideas without which Europe could not have developed as vigorously as it did. Equally important, a substantial and vigorous community of scholars study and publish about Greco-Roman culture in Arabic – Egypt can lay claim to a thousand years of Greco-Roman culture. The most widely spoken language in the former territory of the Roman empire is Arabic – Turkish is probably the second most important (depending on where you draw the boundaries of Roman influence in Germany and Turkey).

We are in a position where we can – where we have an obligation – to rethink and overhaul the study of Greco-Roman culture around the world. At this point, however, I want to shift my focus to the study of Greco-Roman culture in Europe where that subject can and should play a more central role than anywhere else.

Greco-Roman Culture and Europe

We are, in late winter 2022, experiencing a historical moment in which the question of Europe and European cultural identity is a matter of life or, perhaps more accurately, of death. Russia has invaded Ukraine and it has done so on the basis of an identity based much more narrowly on language and religion than would be possible for any nation that joined with the European Union of today or who espoused a European identity that could extend to the Atlantic.

In July 2021, Vladimir Putin, published his argument that the inhabitants of Ukraine, Belorussia and Russia were all one people.6 Putin’s vision of history begins in late 9th century Kyiv and the choice of that starting point allows him to dismiss Greco-Roman culture and to minimize Russia’s ties to the rest of Europe. In his address before the invasion of Ukraine, Putin, by contrast, mentioned Russia’s “European part,” he did so only to specify that this section of the country would be vulnerable to missile attack from a Ukraine armed by NATO and the US. Instead, he declared that “Ukraine is not just a neighboring country for us. It is an inalienable part of our own history, culture and spiritual space. … Since time immemorial, the people living in the south-west of what has historically been Russian land have called themselves Russians and Orthodox Christians.”7 For Putin, an identity based on Russian language and Orthodox Christianity trumps all other ties. Europe/European appears eleven times in the English translation of his address but there is no appeal to a shared European culture or identity. Behind this speech lies the idea of Eurasianism, in which Russia establishes its own, separate culture, based on Slavic language and Orthodox Christianity, exercising control over all the ethnic groups within the vast, if fluidly defined, space of Eurasia. One could wonder whether a European identity for Russia would be equitable for those who lived beyond what is seen as European Russia or who did not embrace a Russian cultural identity. But even a narrowly construed European identity would be far broader and potentially more inclusive than one based upon being Russian and Orthodox.

One narrative that I have found compelling argues that this is a war provoked by the question of who is and who cannot be European. A growing percentage of people in Ukraine have begun to see their future with Europe and with the admittedly imperfect institutions of democracy. Right wing movements in Poland and Hungary reflect the challenges of integrating much more conservative societies with the values of Europe. Surely a substantial portion of such a reorientation reflects a reasonable aspiration for members of Ukrainian society to achieve a level of prosperity comparable to that in Western Europe.

One admittedly anecdotal example came to my attention after I had begun working on this article and deserves, in my view, considerable thought. The current president of Ukraine, Volodymyr Zelensky, represents the “Servant of the People” party. This party, in turn, took its name in 2017 from a Ukrainian comedy of the same name that ran from November 2015 through March 2019. Two months later, Zelenksy assumed office as the actual president of Ukraine. This series is worth study because it reenacts a powerful (and, to my mind, always deeply appealing) myth in democratic societies: moneyed interests manipulate democratic institutions for their own benefit but an initially naive and inexperienced member of society assumes a position of power, rises to the challenge and begins to implement the best values of a democratic society. American audiences may think of films such as the 1939 Mr Smith Goes to Washington8 (in which a naive youth is appointed to fill a vacancy in the US senate and struggles to implement his idealistic plans) the 1993 Dave (in which a temporary stand-in for the American president finding himself acting the part in real life after the sudden death of the actual president).9 Other nations have their own versions of this myth.10 This series as a whole deserves careful attention by anyone observing the situation. The success of Servant of the People as a series demonstrates not only a keen recognition of the challenges that a just democratic society faces in Ukraine but also a deep and widespread belief in, and aspiration for, a democracy that pursues its own ideals and fashions a more just world. Observers with an inclination towards cynicism (such as myself) should watch this series and reflect on what its manifest popularity tells us.

Much as I was surprised at how familiar I found the aspirations in Servant of the People to be, the first glimpse we have of Zelensky in the first episode took me by surprise. I knew that Ukrainian universities supported the study of Greco-Roman culture (although I was not able to find much detail as many university websites had gone offline) but I did not think that we would find hundreds of thousands of secondary school students studying Greek or Latin as we do in France, Germany and Italy and I did not expect Greco-Roman culture to be so prominent in Ukraine as in the western sections of Europe. I was thus shocked when the show introduces the Zelensky character with the following image:

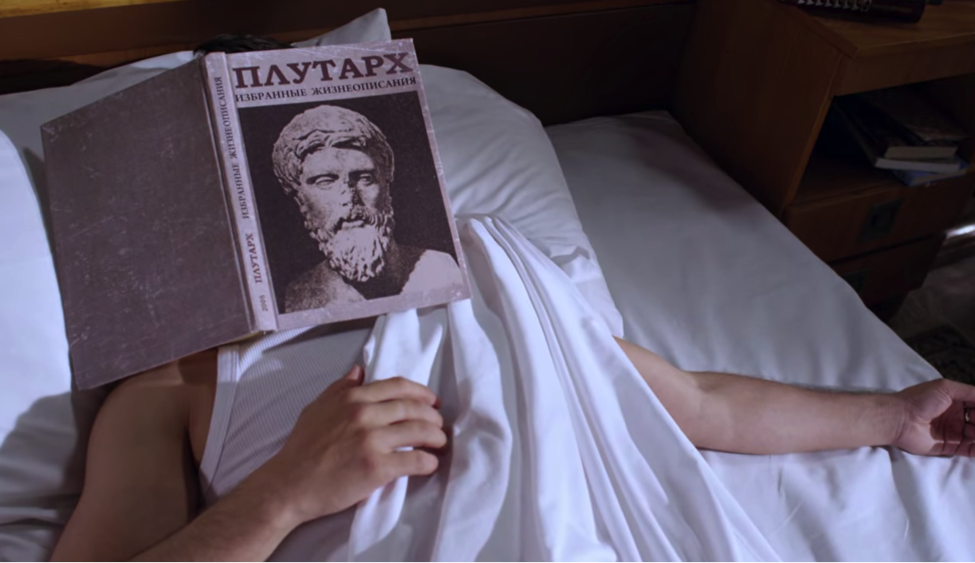

Figure 1: first view of Volodymyr Zelenskyy as Vasiliy Petrovich Goloborodko (soon to be president of Ukraine) in the opening episode of Servant of the People.11

The screenshot above shows us the first view that we get of Volodymyr Zelensky as Vasiliy Petrovich Goloborodko. He is still a simple high school history teacher. He has overslept and will bicker with his family as he scrambles to get ready for work. The book covering his face is surely aimed to present the main character as a slightly feckless, clearly impractical intellectual, a man who falls asleep reading some dusty old text. But students of Greco-Roman culture will immediately see that Zelensky’s face is replaced by the portrait of a bearded man from the Greco-Roman world. Those who can read Greek (if not Cyrillic) should be able to recognize that the author is Plutarch. Those who can read Russian (or who can type the words into Google Translate) will find that the book is not from the Moralia (the many essays that Plutarch composed) but contains “Selected Lives.”

There are at least two points that are relevant here. First, the image may well be intended, initially at least, to satirize the unworldly high school teacher but that satire contains a deeper irony. The unworldly high school teacher will become president of Ukraine and, in so doing, he will become in real life a figure similar to the great leaders whose lives Plutarch uses as models for praise and for blame. And, of course, the even greater irony is that Zelensky would become, in real life, a war-time leader who would justly serve as the subject for a modern Plutarch.

The second point is even more germane to the present argument. The authors of this series chose to use Plutarch’s lives in order to frame our initial view of Zelensky. I am not sure how many viewers will have known who Plutarch was or have drawn the conclusions that I have drawn, but the people who constructed that scene knew exactly what they were doing. I have been unable to find this particular translation online and I even wonder if they created this cover, with an ancient face and Plutarch’s name above it, to make the point: this feckless high school teacher – like so many other initially unprepossessing heroes – would become a Plutarchian leader. The democratic future of Ukraine emerges from the Greco-Roman roots of a wider European culture. And the fact that the translation is itself in Russian serves as an invitation, if not a challenge, to speakers of Russian in Ukraine and beyond to recognize that shared culture.

I write this as an American and, indeed, as an American who is struggling to explore how Greco-Roman culture can play a constructive role in the fashioning of a more perfect union and a more just society in the United States. We in the United States cannot sustain the Eurocentric model that equates Classical Studies with the study of Greco-Roman antiquity. Although I believe that Europeans would fundamentally benefit from developing more inclusive and open models of cultural identity, I am not inclined to lecture anyone about how to make their own societies more just, while my own society has so much to do.

But I also write this as one who was for six and a half years a Professor of Digital Humanities in Leipzig and who treasures my permanent residence card for Germany. I am not a European and, having lived in Europe, I know that, even if I were to return and spend the rest of my life there, I would never be one. I see many challenges and issues confronting Europe. But that distance also has helped me, from time to time, help me see the strengths and achievements of Europe where problems and failings command their attention. I write as a critical admirer of the vision behind, and the world-historic achievement of, the visions that lie behind the European Union of today. I believe that a renewed and reimagined study of the cultures associated with the Greco-Roman world can play an important role in fashioning a more just and, indeed, happier Europe.

I find the study of the Greco-Roman world compelling insofar as it has provided a space by which individuals have explored an identity that helped them transcend the narrower sense of self that that their nation states (or kingdoms or duchies or electorates) have fashioned for them. As Russian forces invade Ukraine, and as I follow events on social media that provide shattering images of death and suffering, I believe even more deeply in the constructive role that a shared, transnational, purposefully generous and expansive study of Greco-Roman culture can play in Europe. While I do hope that European cultural identities will also expand and become more global, Greco-Roman culture should play a larger, if not hegemonic, role in that identity than would, in my view, be appropriate for nations such as the United States.

First, it may seem frivolous, even disrespectful, to discuss reading Ancient Greek and Latin at the present time. As I write this piece, bombs are exploding across Ukraine. Women and children, as well as combattants, are being slaughtered or left suffering in agony. More than a million people have fled their country as refugees. How on earth can anyone think about reading Ancient Greek or Latin? The situation may resemble that of a long-time smoker, suffering from the final stages of lung cancer, being lectured on the evils of smoking. Too little – laughably too little – far too late. But the analogy is imperfect in at least one way. Unless a nuclear holocaust ensues (and that is by no means impossible), the people of Ukraine, of Russia and of the rest of Europe will remain when this immediaate conflict finally ends. The patient will not die – as it did not die in 1945. Now, as the bombs fall and unbearable trauma overwhelms so many, now is the time also, for those of us privileged to sit in quiet offices, to think about how we can help fashion a better future. The Greco-Roman world may not be the most important topic, but it is the topic that I have pursued for more than 50 years and the instrument whereby some of us can most effectively contribute.

Second, I know all too well that the study of Greco-Roman antiquity can advance deeply problematic causes. The use of Greco-Roman antiquity to justify European colonialism, Antisemitism, White Supremacy and a narrow Eurocentric identity have attracted substantial attention in recent years. I myself am, along with my student and collaborator Julia Deen, working to complete a born-digital edition of Friedrich August Wolf’s 1807 Dartsellung der Alterthums-Wissenschaften.12 For me, this is a tragic document. On the one hand, it establishes Alterthumswissenschaft as a dominant term of art for the study of the Greco-Roman world and constitutes a milestone in shaping the academic practices in this field for more than two hundred years. At the same time, where Wolf is best known for his 1795 Latin monograph on Homer,13 he chose to compose the Darstellung in German. He wrote the book after Napoleon had closed the university at Halle, while he was a refugee in a Berlin that was occupied by the French. A very long dedication to Goethe opens this book. Wolf dated the prologue in Berlin, July 1807, the same month as the two treaties of Tilsit, which punished the Prussian king and helped stimulate a broader German nationalism. We may have become better scholars in a narrowly academic sense, but, insofar as we did so to promote nationalist identities rather than a more open, cosmopolitan culture, we lost a larger moral purpose. Now is a good time to rethink and refashion that moral purpose for the 21st century.

While nationalism in Europe surely declined after the second world war and with the rise of the European Union, at least one residual change limited the potential good that the study of Greek and Latin could exert. All Europeans with whom I am familiar learn Latin and Ancient Greek in (one of) their national language(s). I think that I can remember wondering, a half century ago when I was studying Latin in secondary school in the United States, if there were students in countries other than the United Kingdom who were also studying Latin. I think that I vaguely understood that there were, but I had no idea of who or how many they were. Students in the primary and secondary schools of Europe may not be so isolated, but learning the languages in classrooms and with textbooks in the national language can isolate students and fail to communicate to them that, by studying Latin and Greek, they are exploring a cultural background that transcends their identities as citizens of Germany or Croatia, Italy or the Netherlands.

What can be done?

I would suggest one very concrete change to the way in which European students engage with Greek and Latin. I emphasize students because they are, of necessity, far more numerous and, in the long run, far more important than the handful of specialist teachers who instruct them or the even smaller number of advanced researchers who publish specialized scholarship in articles and books that still almost always live behind subscription walls. When we surveyed enrollments for Greek and Latin in Europe in 2014,14 we found more than 3,000,000 students – roughly twenty times as many as study these languages in the United States. Most of these students will forget virtually all the Greek and/or Latin that they learned but the subliminal effects of that education can shape their thinking for the rest of their lives.

This change aims to make the study of Greek and Latin a more transparently and inescapably cosmopolitan act by showing students constantly that they are working alongside speakers of many languages and from many countries, not only in Europe but from around the world. The second of these two changes leverages the fact that the traditional methods by which we have studied and read Greek and Latin help us exploit new methods by which we can engage immediately and deeply with a growing number of the many languages on earth that we will never be able to learn. I will describe how this way of thinking enables me to explore, in my own preliminary way, a topic that I find compelling and vital: the need to make the languages and cultures of the other 19 official EU languages and other non-official languages and dialects become visible in Europe and in the world as a whole. I will also show how this same method allows us to move beyond Europe and begin to engage with traditions from around the world.

First, every person who studies Greek or Latin in Europe should do so while using, at least in part, an online learning environment that has been customized for many different languages. Students from the big languages such as French, Italian, German and Spanish should not only see each other each and every time they log in but also those European languages that 1% of less of their fellow Europeans speak – this starts with Polish and includes languages such s Croatian and Dutch that have substantial groups of learners who are invisible outside of their nations. Each and every time they begin studying Greek or Latin, the range of students should impress upon them that, in learning these languages they are studying a subject that no one nation state controls. They are learning these languages because they have cultural identities that are rooted in a complex European culture that is much wider and older than any political structure now in place. This larger European identity should always push back against trends towards nationalism and a narrower ethnocentrism. Although Europe may not encompass the cultural diversity for which many Americans (myself included) strive, it brings together groups that have visited upon each other enormous violence and cruelty and have dehumanized each other to do so.

Among those who study Greek and Latin are speakers of Russian and Ukrainian. Their numbers are not large and work about the Greco-Roman world published in these languages is, in my experience, virtually invisible. I only know about this community because I have met members of a network of Russian-trained experts in Greco-Roman culture at conferences in Europe (where some of them have positions). At a 2017 Helsinki conference on Latin and the Republic of Letters,15 I had the opportunity to hear Alexei Solopov speak about the use of Latin in 18th century Moscow – a topic that highlights roots by Russian intellectuals in Moscow (rather than just in the typically more European Saint Petersburg). Before the conference ended, he gave me a gift that surprised me: a then brand-new (2016) critical edition of the Oedipus Rex. The editor, Mauro Agosto, was, not surprisingly, from Italy and is a faculty member at the Pontifical University of the Lateran.16 The edition also was hardly surprising in appearance as it resembled, in both its color and the texture of its cover, a typical Teubner edition. What surprised me was the publication location and series: “Academiae Moscoviensis Elisabetanae Lomonosovianae Schola Grammaticorum: Bibliotheca Utriusque Linguae Scriptorum Moscoviensis”17 – a series for editions of Greek and Latin authors published by the University of Moscow. This publication series has great symbolic importance as it is an attempt to show that an academic institution in Moscow can contribute to our infrastructure for the study of Greek and Latin. It brings to concrete form the idea that Moscow and Russia have deep cultural roots in Europe. Russia may well have its own identity (as does, for that matter, Germany, France, the Netherlands, Hungary and every other nation of Europe) but it is also part of Europe. Europe is not the other. If that idea were more powerful, Russia would be a very different country and we would not be witnessing a Russian invasion of Ukraine. And at least one Russian expert on Ancient Greek literature, Boris Nikolsky, faculty member at the Russian State University for the Humanities, Institute for Oriental and Classical Studies, has left his country because of the Russian invasion of Ukraine.18

When I searched for this edition in Worldcat, I found that the editor’s name was miscatalogued (“Maurus Agustus” rather than either the Italian “Mauro Agosto” or the Latin “Maurus Augustus”). Worldcat only knew of two libraries that had copies of this edition: the University of London Senate House Library and the University Library at Halle in Sachsen-anhalt. As far as I know, the only copy of this edition in the Western hemisphere is sitting on my desk as I type. No one in the West seems to have noticed this edition or to have recognized the potential importance of its existence. Our disinterest in this action would only strengthen the argument in Moscow and Russia that we in the West are indifferent to what they do and that people of Russia should not even try to participate in a European society that will look down upon them and ignore them.

I have not yet talked about what such a multilingual environment for learning Greek and Latin would look like because most readers are, I think, familiar with platforms for social media (like Facebook and Twitter) or videos (like Netflix or YouTube) that have been customized for many different languages. And we would need some sort of platform to manage the different users of such an environment for learning Greek, Latin and, I hope, other historical languages as well. I cannot speak with any confidence about how such an environment would work but I can speak to some core features of its underlying architecture and some of the services that it should provide.

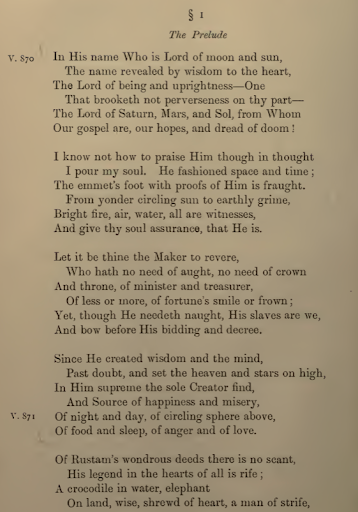

My conclusions are based on an initial experiment that explores how we might fashion a classical studies that fits the aspirations of a nation such as the United States that cannot give to Greco-Roman culture the same level of prominence as may be feasible in Europe. Leipzig PhD student Farnoosh Shamsian and I are working on an environment to support speakers of two modern languages (English and Persian) who wish to learn two different historical languages (Ancient Greek and the Classical Persian of Ferdowsi’s Shahnameh). Our goal is to foster dialogue between speakers of English and Persian and to move away from assumptions of European cultural hegemony. This choice reflects both the importance of the Shahnameh in world literature and a studied attempt to fashion new intellectual and social connections between English and Persian speakers in general, and between people from the Islamic Republic of Iran and the United States in particular. This reflects my own personal experience as one who grew up happy to see the brutal Shah of Iran fall and sad to see the inveterate hostility of the new regime to the United States. Of course, there were good reasons for this hostility (I make sure that each of my students, for example, knows the name of Kermit Roosevent Jr., who played a lead role in the CIA’s 1953 efforts to overthrow Mohammed Mosaddegh, the lawfully appointed ruler of Iran.) The importance of Greek sources for ancient Persian history and the role of Greek philosophy and science in Iran’s own history provide good reasons for Persian speakers to learn Greek. We wish, however, to avoid the impression of a one-sided flow of ideas based on an assumption of European cultural hegemony. Our goal, thus, is to establish a bilateral exchange, with English speakers learning Persian and Persian speakers learning Ancient Greek. The Ancient Greek/Classical Persian, Modern English/Modern Persian pairs, important as they may be, constitute a first step towards a more complex network of modern and ancient language environments. Our work has provided us with concrete experience in the challenges of creating a learning environment for historical languages that can be rapidly customized for speakers of different modern languages.

Some of our observations include the following:

Many of the core components in a born-digital reading environment are machine actionable annotations. Metrical analysis, for example, lends itself to machine actionable form.

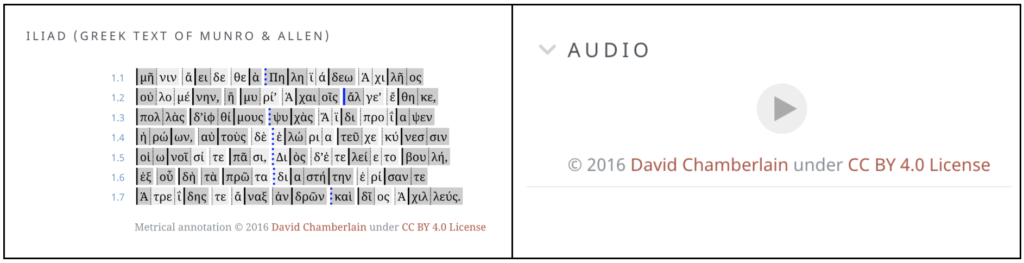

Figure 2: Above left, metrical analysis of the opening seven hexameter lines of the Iliad, with darker shaded syllables being long and lighter short; above right, accompanying recording of David Chamberlain reading these lines.19

Generations of children have grown up watching cartoons where they were urged to “follow the bouncing ball” as it moved from word to word accompanying a song. Some of us may remember that method from our childhood but, in juxtaposing a text with a metrical analysis and performance, we attack a fundamental limitation of print: its silence and utter inability to communicate interpretations of how poetry might sound or be performed. While the number of performances of Ancient Greek and Latin online remain (for now) relatively limited, a range of compelling performances of other works are available either as sound files or on platforms such as YouTube that allow us to link to a particular section of a video. I see for myself the power of this simple juxtaposition. I teach the Iliad each year in English translation and now I can have my students submit a recording of themselves reading a few lines of the ancient Greek in meter. Even if they could do nothing else (and, as I will show, they can do far more with the Greek), they can begin to feel the poetic form as they follow metrical analysis and follow the recording.

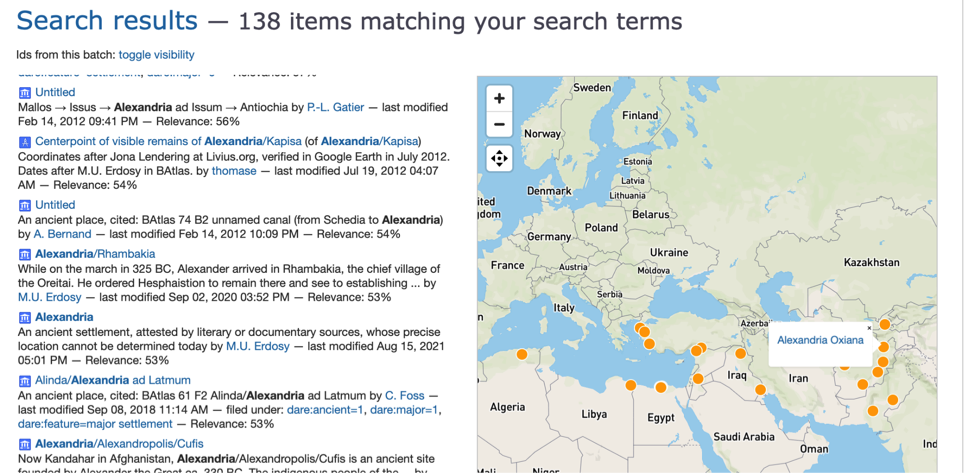

Other classes of machine actionable annotation include identifying features in a source such as the morphological form (e.g., 2nd declension Greek noun), syntax (e.g., one noun is the object of a particular verb in the sentence), grammatical function (e.g., distinguishing datives in Homeric Greek that describe “place where” from those that mean “by means of”), the particular word sense (e.g., stating that the Greek word ârchê corresponds to English “beginning,” “empire” or some other meaning in a given passage), particular place being referenced (e.g., choosing among the various Alexandrias in Figure 3), dates (Nth Olympian), particular person (e.g., Alexander the Great? Alexander Severus? etc.?), or the various relationships between people/places (e.g., city within province, ruler of empire, X is mother of Y).

Figure 3: The Pleiades Gazetteer responds (March 16, 2022) to the query https://pleiades.stoa.org/search?SearchableText=alexandria with the display above. Geotagging links references to the Alexandria in source texts with the entry for the particular Alexandria referenced in that passage.

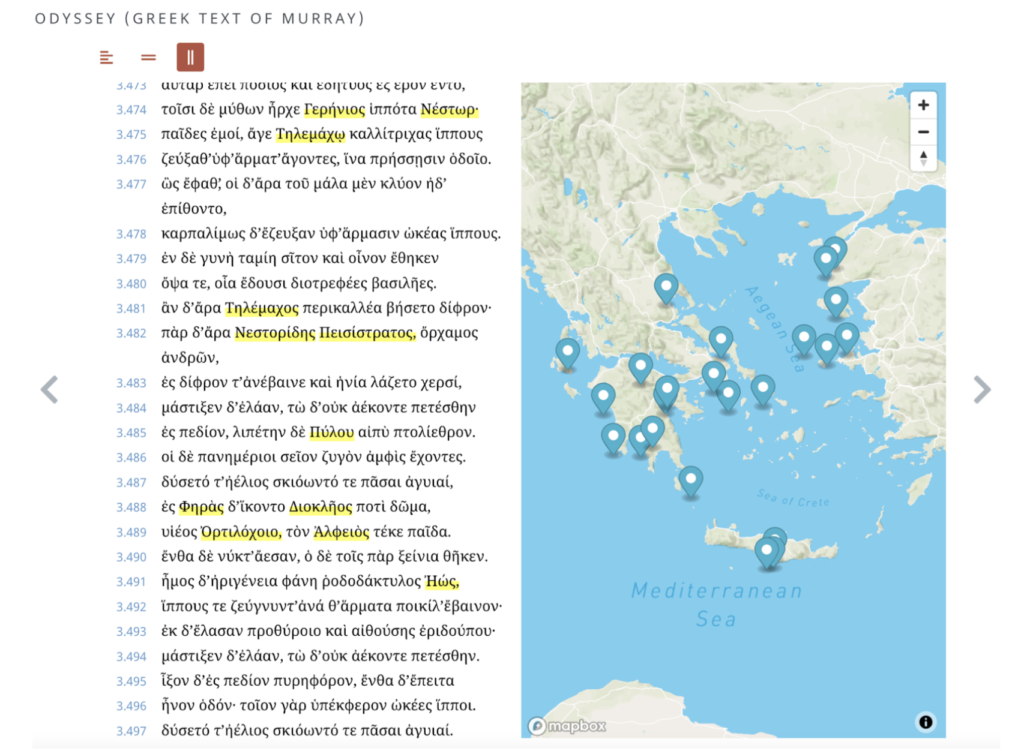

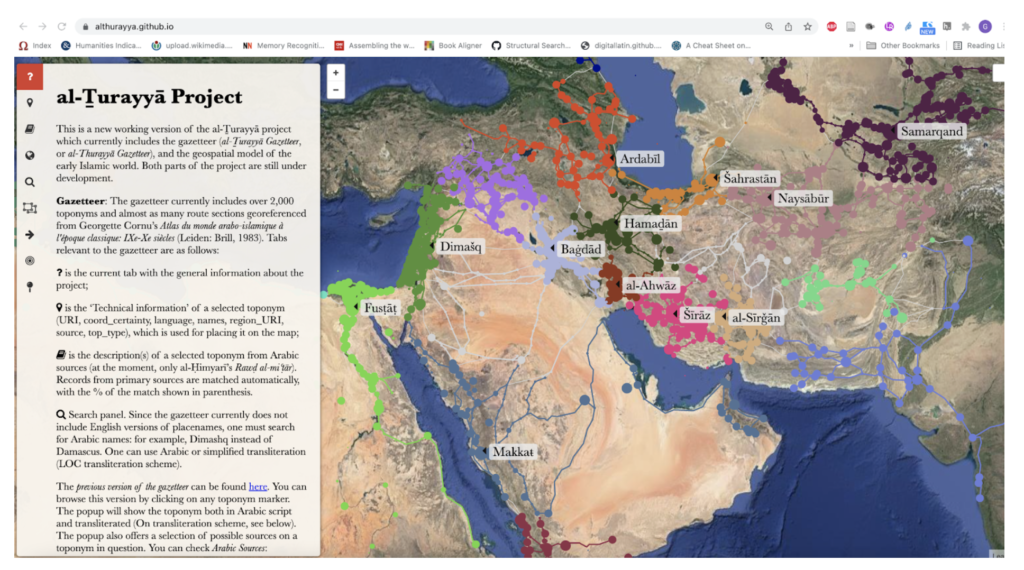

Machine actionable annotations from a source text in a particular language (e.g., Ancient Greek, Classical Arabic) can be used to create visualizations that reveal contents of the source text to a much wider audience. Figures 4 and 5 show two maps, the first plotting locations in the Greek text of the Iliad and the second geospatial data extracted from Classical Arabic sources that have never been translated into English. A reader whose first language is Persian can create annotations for a text in Ancient Greek that can generate a visualization that speakers of any language can grasp – even if they are unfamiliar with the writing system (e.g., an anglophone viewing a map with place names in Arabic or Cyrillic) they can see where the points are located on the map. Social relations and dating conventions differ from society to society but categories of visualization such as social networks and timelines nevertheless can reveal contents of sources to a multilingual audience.

Figure 4: above left, the Greek text of the third book of the Odyssey, with named entities highlighted; above center, a map of place names that appear in this section of the Odyssey; above right, a list of named entities in order of their appearance as annotated by Josh Kemp.20

Figure 5: Place names extracted from Arabic sources and plotted onto a map. The colors differentiate administrative districts. The connecting lines trace routes between places.21

Where social networks and timelines will often need additional information to clarify culturally significant features (e.g., differing categories of marriage or the importance of particular familial relationships in different societies, dates in the calendar associated with particular events in the past), linguistic annotations address the language of the source itself. Consider the opening words of the Iliad – probably the first words that survive in the continuous tradition of European literature:

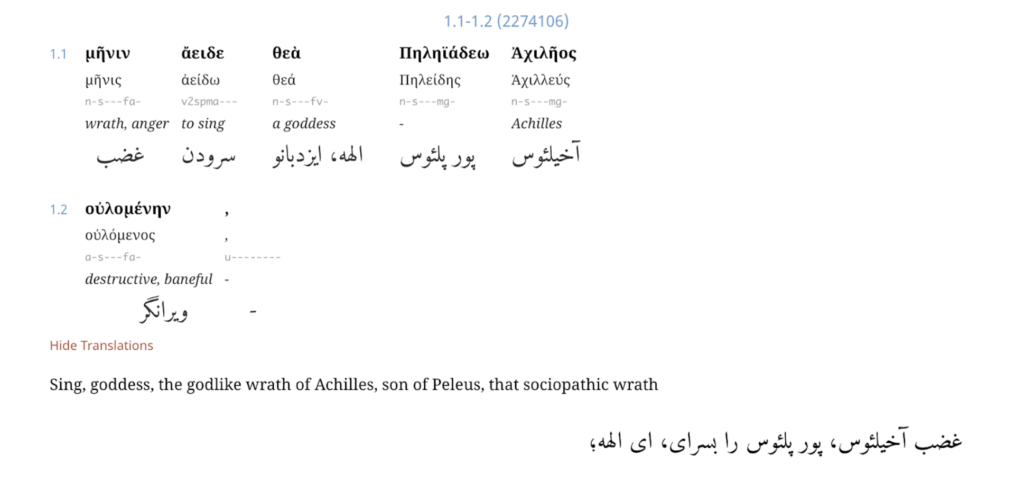

Figure 6: The opening of the Homeric Iliad with token-level annotations, including glosses in Persian, and translations in English and Persian.

The figure above shows annotations that address individual tokens defined as space delimited words and/or punctuation (e.g., the “,” at the end). There is more to be done: we should be able to show the Greek in transliteration and should convert the cryptic part of speech tags (e.g. “n-s—fa-” for the Greek word mênin) into at least notionally more readable forms (e.g., “feminine accusative singular noun” in English). Before considering the token level annotations, let us consider syntactic annotations that link each word in a sentence into a network – normally a special kind of network called a tree (where each node may have many descendents but must have one root, even if that root is a null entity as it is for the starting point of the tree).

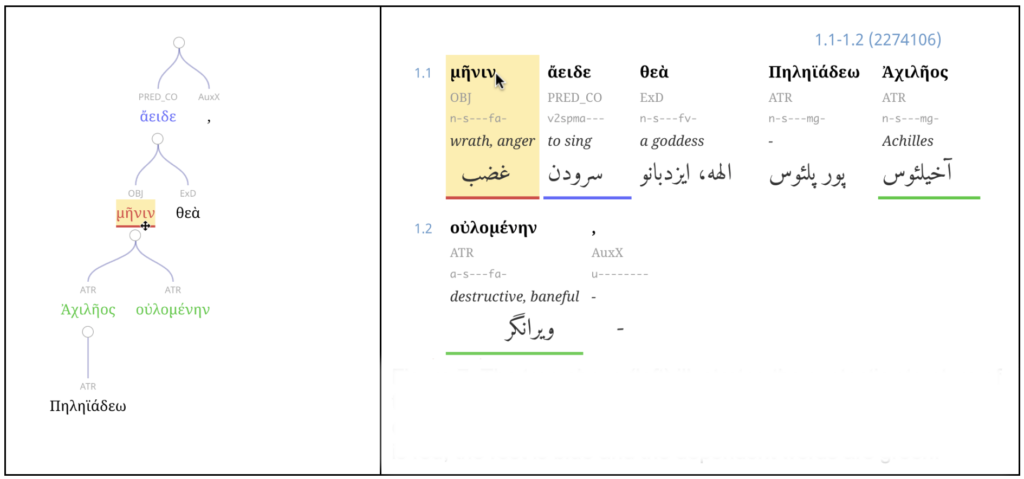

Figure 7: The tree above (left) illustrates the syntactic structure of the opening syntactic unit of the Iliad. In the sentence above we can see the dependencies visualized in place: the word in focus is red, the root is blue and the dependent words are green.22

The tag OBJ indicates (not surprisingly) that mênin is the object of aeide, which is the 2nd person singular present imperative of “to sing” (as glossed above). The tag ExD designates an address – what students of Greek and Latin would call a vocative (“o goddess!”). The words Achillêos and oulomenhn each bear the tag ATR (for attribute) and illustrate why we need multiple layers of annotation. Achillêos is the genitive of the name Achilleus (encoded in the part of speech tag: “n-s—mg-”): the expression can be translated as the “wrath of Achilles.” By contrast, oulomenhn is an adjective, glossed as “destructive, baneful”: it agrees with the word it modifies in gender, number and case and is thus feminine accusative singular (“a-s—fa-”).

The tagset that projects such as the Perseus Ancient Greek and Latin Dependency Treebank and the Index Thomisticus Treebank jointly adopted in the 2000s was based upon work that Czech linguists had developed for their own and other languages. Like Ancient Greek and Latin, Czech is highly inflected and has relatively free word order and so the Czech work was much more adaptable to Greek and Latin than methods (such as constituency parsing) that evolved initially to serve more fixed order languages such as English and French.23 In order to make full use of the Treebank, students needed to understand tags based on a dependency grammar that differed from the grammar that they learned – and needed to learn – in order to understand Greek and Latin. This knowledge is immensely useful for students of Greek and Latin – we can track a completely new set of linguistic patterns by searching the treebanks (e.g., counting subject-object-verb vs. subject-verb-object word orders or tracking which words serve as subject and objects of which verbs). Indeed, the appearance of Treebanks enables – and indeed requires – that we revisit fundamental reference works such as grammars and lexica. We may not change our overall models of syntax, semantics and lexicography but we can at least quantify the frequency with which different features appear and then link each instance of a linguistic feature to the grammar or lexicon entry. Such data can be immensely useful for introductory learners because learners could then see precisely which linguistic features appear, where they appear and how often in the corpus that they wish to read.

In the years since projects such as the Perseus Ancient Greek and Latin Dependency Treebanks, the Index Thomisticus and the Norwegian Proiel Treebanks (which had a somewhat different annotation scheme), the Universal Dependencies (UD) framework has emerged to support “consistent annotation of grammar (parts of speech, morphological features, and syntactic dependencies) across different human languages.”24 Of course, specialists in different languages will develop annotation schemes to probe particular features of interest to them. And, of course, universalizing categories for anything are problematic. Nevertheless, there are, as of March 17, 2022, more than 200 UD treebanks in 100 languages.

For the Perseus Ancient Greek Dependency Treebanks that we have created, there is no downside to a transition to UD. We can represent everything that we capture now in the UD framework and the UD framework also provides more developed guidance for managing tricky features such as ellipsis (e.g., “I saw three hawks and you saw two”). Equally important, by shifting to UD, we move to a technical infrastructure supported by a far larger community than those currently annotating Greek and Latin texts. Automatic conversion from the current annotation scheme to UD is not (yet, at least) perfect but it is good enough to begin the transition. Certainly, we should shift immediately to UD for new work developing Greek and Latin treebanks.

Morphology and syntax are not by themselves enough for readers to understand the basic meaning of source texts or even to account for the relationship between the source text and a pre-existing, literal translation. We need another layer to explain the usage of particular forms in particular contexts.25 Ancient Greek has a dative case which can have a number of meanings in different contexts. We want to be able to explain to readers that a word in the dative case in one passage because the dative indicates location vs. means. In the Iliad, for example, physical combat is a central theme and the verb ballô, “to strike someone with a projectile,” commonly has dative nouns modifying it, each of which is tagged as ADV (“adverbial”) in the Perseus treebank but which can play two very different roles: Homeric heroes can strike each other with various objects that can be thrown (e.g., spears, rocks, arrows) but we also find datives marked as adverbial describing where things are thrown: Achilles throws the speaker’s staff on the ground (Il. 1.245) and tells Agamemnon to cast what he hears into his mind (Il. 1.297). The extra layer of annotation allows us to disambiguate instrumental datives (strike with an object) from datives of location (throw/put something in a location).

Annotation of grammatical categories can be particularly helpful for those who wish not simply to examine individual passages but also to learn the language. If we classify, as best we can, each instance of the dative in the learner corpus, we can (1) tell learners how often they will encounter each usage (rather than presenting a long list of possible uses, some of which they will never or rarely see) and (2) then allow them see as many examples as they like. Consider again, for example, the dative case in ancient Greek. Based on a variety of Greek grammars, we have settled on fifteen different ways in which the dative case can convey meaning. If we use the first book of the Iliad as a learner corpus, three of these categories do not appear at all and are not immediately relevant. Half of the remaining 12 account for almost 90% of all datives (183 of 221). The most common use, where dative marks an indirect object (as in “I gave it to him”, where “to him” is dative) accounts for just under 40% (97). The next two uses both occur 28 times and one of these, where the dative expresses location (e.g., “in his heart”, “on his shoulders”), does not occur in standard Attic Greek and would be irrelevant to those with a learner corpus based on classical Greek prose.

We need, and will always need, explanatory materials about Greek and Latin language, history and culture that can only be expressed in expository prose. In practice, readers will increasingly exploit increasingly powerful machine translation to work with materials in modern languages that they do not know. I believe that academic authors who work on foundational components of our scholarly infrastructure such as editions (which, in my view, should include scholarly translations), commentaries, encyclopedias, lexica, and grammars, that are designed to serve their audiences for decades will need to rethink how they work. Articles and monographs – works published as the opinions of particular people at particular times – must circulate under a Creative Commons license that ensures that the original language of the publication is preserved. Those who publish reference works must adopt an open license that allows others to revise their work – they can exploit versioning systems (such as Github at present) to distinguish their work from the contributions of others. Further, we need to begin learning how to write with sufficient clarity so that machine translation can render our prose into other languages as accurately as possible.

Machine actionable annotations can be rapidly localized into different languages. Authority lists already collect the names of people and places as they appear in different languages, thus laying the foundation for automatically generated maps and social networks with names in many different languages. Documenting the meaning of specialized annotation schemes such as the Universal Dependency framework is a relatively compact job – especially since the best way to understand how the tagset works is to see many examples of each tag or configuration of tags. Traditional textual notes lend themselves to being represented as machine actionable annotations. Students of Greek and Latin take for granted their ability to parse out the cryptical abbreviations of an apparatus criticus based on abbreviated Latin. We may assume that machine actionable textual notes are a luxury.

To illustrate the need for, and utility of, machine actionable structure for our sources, I will consider the most recent edition of a prominent work in World Literature that virtually no Europeans are able to read in the original. European scholars produced critical editions of the Shahnameh from 1811 (when Mathew Lumsden published the first volume and only volume of his planned edition in Kolkata) through 1971 (when the Academy of Sciences of the USSR completed the “Moscow” edition). In 2008, however, the Iranian scholar Djalal Khaleghi-Motlagh led the production of a new edition based on the newly rediscovered earliest surviving manuscript that had been produced in 1217. The most widely used English translation, published by Dick Davis, drew on an earlier version, and still incomplete, of this edition.26 The Khaleghi-Motlagh edition is not only a monument of scholarship but also of scholarly self-determination, with Iranian scholars establishing the state of the art edition for the national epic of the Persian language, a space that extends into Afghanistan, Tajikistan and beyond. One could make a good argument that the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition is historic in that Iranian scholars have, in creating the best edition yet produced, decolonized the Shahnameh. Recognizing that achievement would, in turn, convey respect and constitute a concrete instance where scholars from the traditionally dominant scholarly networks of Europe and North America, Australia and New Zealand welcome the emergence of partners from nations such as Iran.

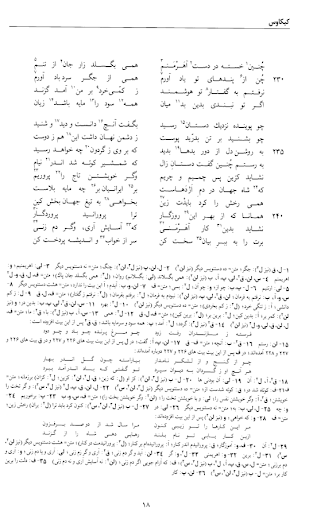

We can, however, only recognize the importance of an achievement such as the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition if we are willing and able to build upon it. In practice, the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition is, as a static print source, virtually unknown and unknowable to anyone who is not a specialist in Persian literature outside of Iran. Consider then a randomly selected page from the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition of the Shahnameh.

Figure 8: a page from the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition of the Shahnameh.

What can be done with this page? Even if we do not know Persian, the form of the page is clear enough for those who are familiar with scholarly editions. Each line of the Shahnameh has two parts and the two parts are visible as separate columns. ٰEven if we cannot read actual Arabic numbers, readers of Greek and Latin texts will probably recognize that we have a number marking every fifth line. The particularly careful reader might be able to learn how to decode these numbers by looking for the raised notes which start at 1 (۱) for each page. By the end of the third line, we get to 10 (۱۰) and thus, having seen each number in sequence from 1-10, could recognize interpret the line numbers as 230, 235, and 240 – thus the page includes line 234-242 – but of what? The header in the upper right hand side کيکلوس, can be fully transliterated because its two syllables contain long vowels (short vowels are not normally encoded in Persian as in Arabic and Hebrew). Again, readers of Greek and Latin editions will immediately recognize that the bottom of the page contains textual notes. They may even rightly guess that the textual notes include lines that have been deleted from the reconstructed text above – the number of verses in the Shahnameh varies substantially from manuscript to manuscript and editors creating a single text must constantly decide what to keep and what to omit.

The immense achievement of the Khaleghi-Motlagh edition is, as noted above, unknown and unknowable for those who do not know Persian. A first, easy step would be to align the most widely used English translation, that by Dick Davis, to the Persian edition. Consider the 20th century Warner poetic translation of the Shahnameh:27

Figure 9: A page from the Warner translation of the Shahnameh with citations to the Vullers edition of the Persian text.

While this translation has been criticized for its archaizing language, it includes in its margins references to the pages in the Vullers edition of the Persian that correspond to their English. Very very few of their readers may know Persian, but they invite those that do to compare their work to the original. Davis, by contrast, assumed – quite reasonably – that, if any of his readers wanted to look at the Persian, they would be specialists who could align source text and translation on their own.

Adding citations to a translation that leads back to the original makes a great deal of sense in a digital age. First, those citations can be hidden if the reader simply views them as a distraction. Second, and more importantly, the growing panoply of reading services that we can see applied to the Homeric Iliad can transform what interested readers could derive from the source text. Furthermore, if the logical structures implicit in the textual notes were encoded in a machine actionable form, readers could ask to see the text as it appears in manuscript X vs. manuscript Y, comparing the version with and without the lines that had been deleted from the main text. We should be trying to make the text and our decisions about how to reconstruct the text as transparent as possible to the widest possible audience. If we have full linguistic annotation (including glosses and sentence level translations) not only for each word in the reconstructed text but for each variant in the textual notes, then readers can also begin to assess the full record of the text and the achievement of the editor. When we think about sharing Greek and Latin, we should think not just about students in areas such as Europe and North America but also in places like Iran who may find our editions as inaccessible as we (currently) find the monumental Khaleghi-Motlagh.

There is much to say about the development of born-digital translations that are designed to interact directly with the source texts that they translate. I think that we will move back to the model that the French publisher Hachette published in the 19th century, which included both a literal and a more literary translation for each text. This series focused primarily on Greek and Latin texts but it also included works in Arabic, German and Italian.28 In our work developing such translations for book 1 of the Iliad and book 5 of the Odyssey, our goal was to reveal the workings of the Greek to speakers of English and of Persian as clearly as possible – there are already multiple inexpensive and engaging modern translations.

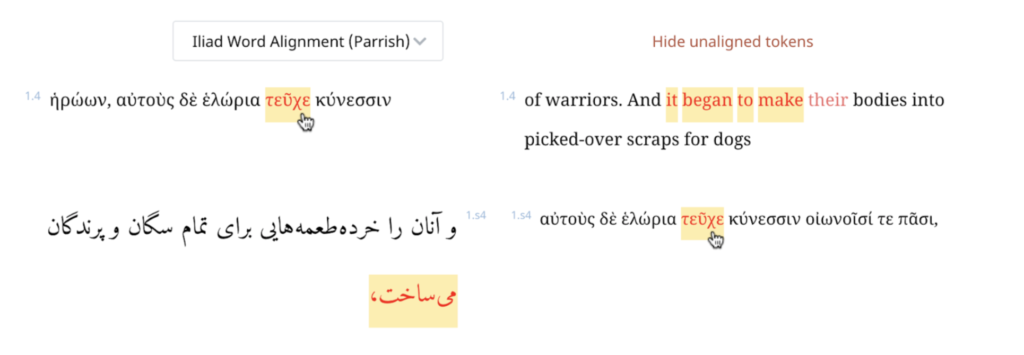

Figure 10: Iliad 1.4 in a born-digital Greek to English and Greek to Persian translations aligned at the word and phrase level.29

The visualization above allows readers to explore the relationship between the source text and the translations. The English word “their” is in red because it does not correspond to anything in the Greek (literal translations have commonly used italics to communicate that a word in the translation has been added). The reader has moused over the Greek word teuxe and can see that it has been translated: “it began to make.” This rendering is designed to highlight the fact that the verb is in the imperfect tense and that the imperfect tense describes an action that takes place over time as a process. We tried to translate each imperfect form in Iliad 1 to reinforce this point.

The combination of a translation aligned at the word and phrase level with morpho-syntactic annotations opens up new possibilities for language learners. The goal is for learners to see how often a grammatical construction (such as the imperfect indicative active) appears in the corpus they are studying. We began our work with a textbook on Homeric Greek that had the students spend the year learning everything they could about this learner corpus. Learners would see that there are 73 instances of the imperfect indicative active and would then be able to look at as many examples as they wished. The reading environment is designed to help them look at the Greek verbs even when they know none of the Greek words: they could recognize the form and see the aligned translation. A side effect of this will be exposure to the same sentences, over and over, through the course of the year, with each new exposure based on something new that the students have just learned.

But even for those who do not know ancient Greek, the combination of morpho-syntactic annotations and aligned translation allows them to begin working directly with the source text. In Figure 6 (above), the Greek word mênin is translated “godlike wrath” rather than just “wrath” or “anger” (as most English translations do). This translation reflects a particular interpretation of the Greek word. The reading environment that we have built allows readers to explore this interpretation by looking at every occurrence in the Iliad and Odyssey of the Greek word mênis (using its nominative singular dictionary form) with Greek text, translation, and morpho-syntactic annotations. Not every scholar would agree with translating “godlike wrath” but I teach the Iliad to students in English translation each year. I always have them look at passages where mênis occurs, to look for the corresponding word in the English and then to tell me what they learn. Working in small groups they almost always report that mênis is the anger of gods and of Achilles. Whether or not we choose to translate this then as “godlike wrath,” the readers all come away with a realization that they can see patterns in the Greek that the translation alone would never reveal.

What can be done? Greek and Latin for a Europe and Beyond

The modern study of historical sources depends upon an increasingly dense, interrelated and expressive set of machine actionable annotations. These annotations can be quickly deployed in multiple languages. Fully functional environments for the study of historical cultures and their associated languages requires a great deal of labor and thought. Language instruction needs to bridge the gap between the learner language and the target language (e.g., students of English are not as familiar with the idea of highly inflected words as speakers of Russian and Croatian, while speakers of Russian and Croatian have no experience with definite articles). More general cultural understanding requires even more thought. Speakers of Persian who study Homeric Greek will almost always interpret the Iliad and the Odyssey in light of expectations about epic poetry that they acquired in their experience with the Shahnameh. Simply translating introductory materials from French or German in Persian will not match the needs of this audience.

Each automated process may provide useful results on its own but those results will for the immediate future provide a starting point that human labor will review, revise or replace. Machine translation from Ancient Greek and Latin may catch up with ongoing progress made for modern languages and provide rough initial translations to accompany pre-existing, curated or uncorrected, automatically generated annotations about morphology, syntax, glosses, people, places and other topics.

The technology of 2022 already allows us to develop a multilingual system that allows its users to recognize, at all times, that they are working side by side with others from around Europe and beyond, that they are building on many kinds of work produced by members of this international community, and they too can make contributions that can serve readers of many different languages. Services within such a system could quickly include:

- A virtually unbounded set of exercises that can be generated from the various annotation sets, that can be quickly localized into new languages and that allow learners to practice and assess their skills. Easily localized tasks include:

- matching inflected word to its dictionary entry

-

- ability to prioritize vocabulary acquisition based on frequency

-

- part of speech identification (e.g., recognizing optative verbs)

-

- ability to prioritize the study of tense and case systems on frequency

-

- paradigm formation (e.g., recognizing how different nominal declensions generate inflected forms)

-

- ability to prioritize paradigms based on frequency

-

- grammatical function:

-

- ability to prioritize grammatical functions based on frequency (e.g., recognizing constructions such as the genitive of price)

-

- matching inflected word to its dictionary entry

- Extensible discussions about the meanings of Greek and Latin terms based on examples from online sources (e.g., exploring the differences between words that may be translated the same way but have very different meanings, such as erôs, “sexual desire,” and agapê, “christian affection,” each of which are conventionally translated into English as “love”).

- This provides an opportunity for speakers of many languages to create example sentences in their own languages.

- Cumulative heatmaps showing which passages of which authors are being read in different parts of the world. What are people reading? What are they neglecting that might be of interest?

- Here the goal is to make readers aware of who else is out there and where they are from. Greek and Latin are studied not only in big nations of Western Europe such as France, Germany, Italy and Spain but also smaller European countries such as Croatia and the Netherlands, and outside Europe in Egypt and Braziil as well as in the United States and Canada.

- Visualizations showing what annotations have been produced for particular texts

- Here one goal can be to invite contributors to add new annotations or correct machine generated annotations. Review of new annotations can be facilitated by having multiple contributors independently annotate the same passages and then focusing human editorial review on places where annotators diverge.

- Visualizations showing which editions of which surviving works in Ancient Greek and Latin are, or are not, available already as curated TEI XML.

- Here the goal is to identify works that individuals can adopt and correct, starting with text automatically generated from page images.30

- Reader driven question and answers on various topics in Greek and Latin sources

- The New Alexandria Foundation already has developed an infrastructure that can support full text annotations by particular people on particular passages.31

- Optional leaderboards in which individuals can publicly advertise, and/or selectively share. their achievements. Achievements could include:

- Performance on the various examination types localized into multiple languages. This would provide students who are not from well known programs or from larger countries with an opportunity to advertise and document their skills.

- Contributions to various tasks, including

The features above constitute only an initial set of suggestions. Much more obviously could be done going forward but each of the services above could be implemented with the technology and data already available under an open license. The point is not to create a perfect system. The goal is to create a system that lets students of the Greco-Roman world (or, at least, people reading primary sources about the Greco-Roman world) constantly realize that they are participating in a community that belongs to no one nation or culture or modern language.

An Expansive Application of Classical Texts

I hesitate to use terms classical texts and classical studies – even if we demonstrate that such terms include sources in many different languages and from many different cultural contexts from beyond as well as from within Europe – because I do not want to exclude sources from consideration. Greek and Latin texts can, however, be constructively classical if they are treated as spaces in which we learn to think about sources in languages that are foreign to us and from cultures to which we do not have immediate access. My personal goal is to transform our ability and willingness to look beyond our own cultures and languages. The 21st century has transformed our ability to do so. When I was sitting in on Mandarin classes at Tufts in the 1990s, I still had to walk across campus to a language lab, where I would check out cassette recordings and use a tape recorder to practice drills. Access to authentic source materials required extra effort. VHS tapes had, indeed, begun to make foreign language movies much more available, but selection was limited and only economically prominent works would be available for sale.

Now the internet has transformed what is visible and accessible to us – if we choose to look and we make an effort to understand what we find. As mentioned above, the Ukrainian series Servant of the People is available (as of March 2022) on Netflix. If we turn away from the carefully curated (and licensed) content on more traditional platforms such as Netflix and consider a more user-driven space such as YouTube, the range of materials becomes dizzying. Detective series from the former East Germany, movies produced for the strong men of Soviet-dominated eastern Europe, videos about Timbuktu and West African history in Bambara and Arabic as well as English, Latvian pagan metal bands that sing about the history of Latvians and the disappearance of the last speakers of Old Prussian – there are more materials from more different cultures in more languages than I ever could have imagined encountering. There is far more available than I can ever experience, much less study deeply.

When I began living in Germany as a Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Leipzig in 2013, my attitude towards language changed profoundly. I had always been proud that students of Greco-Roman culture were expected to understand scholarship in English, French, German and Italian. If someone gives a lecture in any of these languages, we are expected to understand what is being said – or at least sit attentively and feel guilty if we cannot follow what is said. When I began working with Neven Jovanovic of the University of Zagreb, my perspective changed profoundly. Neven works on early modern Latin authors from Croatia. For them, it mattered very little that they grew up speaking a language that few outside the Balkans understood. Latin was the international language of European publication, a language that belonged to no one and thus to everyone.

The shift to the big vernaculars such as English, French, German, and Italian was a cultural disaster for Europeans who spoke one of the many other languages that were not hegemonic. If we add Spanish to the list of widely understood languages, these leaves speakers of nineteen out of twenty-four official EU languages isolated: if you are a speaker of Croatian or Polish or Hungarian or Dutch or Swedish or one of the other 19 languages (not to mention languages such as Catalan that are not in the official list), you need to choose a more widely spoken language if you are to reach a European audience. Virtually no one will ever understand you if you speak in the language that your mother used when you were small. Virtually no one will understand your jokes or the particularities of your history and culture. Speakers of the big languages can angle for position and push people to use English, French, German, Italian or Spanish, all other languages are disenfranchised.

Few of us – and certainly not me – could become proficient in, much less master, 24 languages. And if we did master the languages of Europe, what about the 22 official languages of India? What about Arabic and Persian, Mandinka and K’iche?32 Language does not scale. We live, and always will live, in a tower of Babel. And only monophone speakers, like anglophones who float through the world in a bubble of English, should think that reliance upon translation is adequate. One of the primary benefits of studying languages such as Ancient Greek and Latin is to experience the limitations of translation. And, indeed, the study of sources from such a truly alien space as the Greco-Roman world gives us an opportunity to reflect on the limits of what we can fully understand.

Greek and Latin sources, however, offer another advantage. They can be constructively classic if we consciously use them to practice methods by which to understand sources in the many languages that we will never be able to master. For millennia, we have learned Greek and Latin by parsing our texts, asking ourselves (and our students) what is the main verb? What does this word depend on? What is the morphological analysis of this form and why does it have that form? We have been thinking in terms that are very similar to the machine actionable annotations that I showed above for Homeric epic.

Universal Dependency (UD) treebanks are now available for more than 100 languages. Stanza, a Python NLP package for “many human languages” uses the UD treebanks as training data and offers core linguistic annotation services online (http://stanza.run/) for (by my count) 67 languages. If we combine uncorrected output of Stanza with uncorrected machine translation and with the habits of parsing texts that we practice with Greek and Latin, we can begin to push far more deeply into sources than is possible if we had professional translations alone.

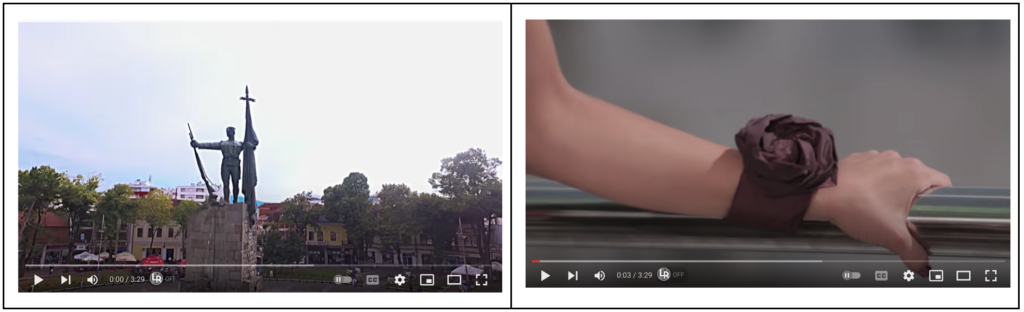

In teaching epic poetry to my students, I always introduce them to the fieldwork that Milman Parry and Albert Lord conducted in the former Yugoslavia in the 1930s. I wanted to find videos of people performing the gusla, the stringed instrument with which the oral poets that Parry and Lord accompanied themselves.

This led me to videos illustrating the use of the gusla in Serbia today and this in turn led me to a collection of contemporary performances in Serbian that memorialize the sufferings of the Serbs over time and the loss of Kosovo. In 2012, for example, the 14 year old Bojana Pekovic achieved prominence with a performance on the Gusla of poetry that sounds to the uninitiated very similar to recordings of Southslavic oral poets from the Parry/Lord collection.33 Neither of these performances includes a transcript of what she is singing. A performance by Bojana Pekovic several years later does, however, include the lyrics. In 2022, YouTube reports that the recording was added six years ago, so the performance was in 2016 or earlier. I will consider the earlier performance, which includes a visual recording of the performance and its context.34

The credits allow us to identify the setting as Kraljevo, a city of 70,000 in central Serbia. Pekovic and her group perform on top of the hotel Turist. A Serbian audience would quickly parse images that appear in the opening three seconds. As often on YouTube, the visuals complement the meaning of the words. In some cases, the visuals tell a story that we can begin to interpret even before we have access to what the lyrics mean.35 The video opens with a view of the Monument to Serbian Soldiers who died in the Balkan Wars and in the First World War. The scene briefly captures a dark red, cloth flower on one of the performer’s arms – a symbol that evokes the battle of Kosovo in 1389.36. Even before we hear a word, the smiling young performers overlooking the central square of Kraljevo are commemorating the losses that Serbs have suffered over time.

Figure 11: Opening shots from a Serbian music video showing (left) the Monument to Serbian Soldiers who died in the Balkan Wars and in the First World War and (right) a flower that evokes the battle of Kosovo in 1389.

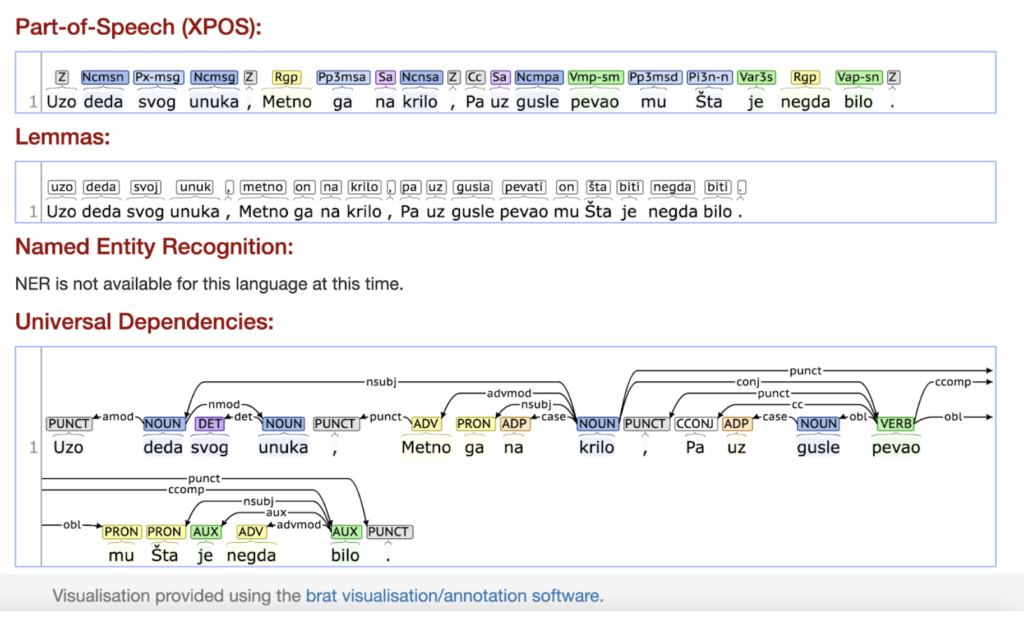

The lyrics are by the Serbian poet Jovan Jovanovic Zmaj (1833-1904). The title, Deda i Unuk, can be easily translated: “grandfather and grandson.” The lyrics are available on the YouTube site (and, happily, long in the public domain). No translation is available but I offer the Google Translate rendering for the opening two sentences:

| Uzo deda svog unuka, Metno ga na krilo, Pa uz gusle pevao mu Šta je negda bilo. |

He took his grandson’s grandfather, put him on his lap, and sang to him with the fiddle What used to be. |

| Pevao mu srpsku slavu I srpske junake, Pevao mu ljute bitke, Muke svakojake. |

He sang Serbian glory to him And Serbian heroes, He sang fierce battles to him, All sorts of torments. |

Figure 12: Opening sentences of the poem that the YouTube video uses as lyrics with translation generated by Google Translate on the right.

There is obviously something not quite right about the translation of the first sentence. If we turn to Stanza, however, and set the online interface at Stanza.run to Serbian, we get substantial linguistic data:

Figure 13: Linguistic annotations of the first sentence (above) produced by Stanza.run.

The word unuka is tagged as “Ncmsg,” which certainly means common noun (Nc), masculine singular genitive (msg). I learn that the dictionary form of unuka is unuk and I can find out from Google translate that this means “grandson.” The adjective svog modifies unuka (and is thus also masculine singular genitive). When I query GT about the meaning of svoj (dictionary form of svog), GT reports that it means “own” – and the Latinist in me suspects that I have a cognate with Latin suus, “his, her.” I am still not sure of how the sentence works, but it clearly has the “grandfather” as subject, perhaps as “grandfather of his grandson.” The core meaning is clear: the grandfather put his grandson in his lap and began singing to him about the past. We could identify the function of almost every word in the Serbian and align it with the English.

The next sentence tells us what that past was like: the glory of Serbia (srpsku slavu) and Serbian heroes (I srpske junake), as well as battles (bitke) and torments (muke). What we are seeing is a young woman performing a song for a Serb audience (some of whom are following in the central square below during the recording and some are watching the untranslated YouTube video). The performance reenacts the process by which one generation transmits the memory of Serbian suffering to another, authorizing both that transmission and the importance of holding onto the sufferings and wrongs from the past.

The machine translation and linguistic annotations allow me not only to capture much of the basic meaning in this poem but also to identify key terms. As I write in early 2022, I have become familiar with the phrase slava Ukraini, “glory to Ukraine.” I also know that the response to this is Heroiam slava, “to the heroes glory!”37 I can immediately see that we are working with the same basic Slavic word for glory in both the Serbian and the Ukrainian (slava/slavu). I also see that the juxtaposition of glory/fatherland/heroes appears as a greeting in Ukrainian and as the opening of this poem. Glory to the country and to the heroes seems natural enough but it is not a collocation that I believe to be common in English. This suggests to me that I have a fixed phrase to open discourse that appears in more than one Slavic tradition.

At this point, my training as a philologist also comes to my aid because it tells me that I do not have enough information. I have more questions than answers. If I had a large corpus of 19th and 20th century sources, I could study the uses of slava/slavu. I could see what wins glory – conquest? defending the homeland? writing patriotic poems? Where else and how often do I find this collocation of homeland and hero? And I note that the Serbian use junake rather than the Greco-Roman heroiam – without the English translation, I would not have been able to infer that I was dealing with heroes in both cases. If I wanted to pursue this topic, I know I could not only find native speakers to query but that I could probably hack together a big enough corpus to begin pursuing patterns myself with the aid of the digital tools at my disposal.